Torah & Rationalism – Writings of the Gaon Rabbenu Aaron Chaim HaLevi Zimmerman zt”l (Feldheim 2020, 216pp.)*

Ovadya Hoffman

Deviating from conventional book reviews I shall not enter into a discussion of the author – R. Chaim Zimmerman’s genius, schooling, breathtaking erudition, oeuvre, philosophies or his broader Weltanschauung. I leave that for the biographers, that is, if any will take up the challenge.[1] Nor does this survey qualify as a comprehensive book review as I will explain later on.

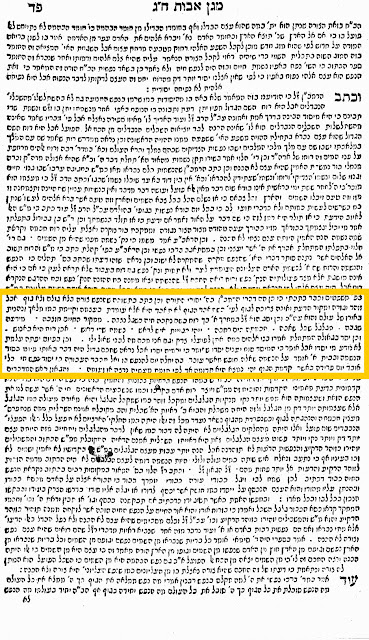

First, a word on the book itself. When a posthumously published book appears any critical minded reader wonders where the material came from, in what condition it was, did the publishers do any editing at all to the materials etc.? These are very important questions with serious ramifications and any responsible publisher should want to provide as much detail as possible. Unfortunately, in the present book we are presented with a vague picture. The reader is only informed (Preface, viii) “The text presented includes redacted variants of articles published during the 1980s under the headline Torah and Logic.” No precise list of the publications’ previous appearances is given, a proper bibliography, no exact description of the redactions or even who committed the redactions – the editor, Moshe Avraham Landy, or R. Zimmerman himself. One example, which relates to the section I’d like to focus on, is Landy’s note on p. 131 n. 265 (duplicated in the Hebrew section, p. 174). He informs us that R. Zimmerman “compiled a page by page critique of Professor Ginzberg‘s A Commentary on the Palestinain Talmud that shows most of the sources quoted by Ginzberg are found explicitly in earlier lesser-known printed books on Talmud Yerushalmi; and any chiddush, or “original idea”, offered by Ginzberg could also be found in sefarim and books of previous rabbis and scholars. This critique was written about 1950, and for various reasons was not published. Some galley proofs and other remnants of this manuscript are in the archive of the collected writing of the Gaon Rabbenu… They are presented herein for the reader in the original Hebrew…” I am unsure if what is presented are pieces of a longer manuscript which runs “page by page” (on all three volumes of the Commentary and the posthumously published fourth volume) or if this is the complete critique which, in its current composition, only encompasses the first eighty or so pages of the first volume. Again, a precise description and an unequivocal report of the materials would have obviated any confusion.

CHAPTER IX – The Falsity of Chochmas Yisrael

I shall focus on R. Zimmerman’s charges leveled at Professor Louis Ginzberg’s Perushim VeChiddushim BaYerushalmi (herein, “Commentary”); specially the explicated charges mentioned in this chapter as they are reflective of the criticisms in the Hebrew recension, “רצנזיה” (Appendix, 175ff.), which will not be treated in this essay. I do not think such a presentation is misrepresentative or fragmentary of R. Zimmerman’s complete critique since he himself maintained that “[f]or the intelligent reader, the following evidential examples should suffice” (p. 131). Additionally, I resisted from responding to the cryptic one-liner allegations sprinkled on the preceding pages (pp. 127-130) since I’m not at all sure to what precisely R. Zimmerman was referring to and are, supposedly, detailed only in the Hebrew section. I surmise that the citations to the Commentary referenced in the notes of those one-liners were provided (or, suggested) by the editor of the manuscript, either Landy or Rabbi Eliyahu M. Zelasko (cf. p. 175). Finally, to assay the buildup and the opinions expressed in the chapter of the wider “Falsity of Chochmas Yisrael” is more tedious and requires a much more in-depth systematic debate as it relates to their different schools of thought, principles and religious philosophies, which is entirely beyond the scope of this scrutiny. This review is not intended as a rejoinder or an exculpation of Chochmas Yisrael, its “truthfulness” or its fidelity to Halachah and tradition. In this brief register it is strictly Ginzberg’s [rabbinic] scholarship I attempt to address in light of R. Zimmerman’s allegations; not the man, his beliefs or his affiliated institution(s). Transliterations below follow the method employed in the book under review. Emphasis, in italics, are of the current writer.

P. 127

He [Ginzberg] writes in his book that he developed a novel approach and a scientific method to Halachah.

These are Ginzberg’s actual words (English intro., viii):

In these volumes an attempt has been made to deal with the writings of the mishnaic-talmudic period as a unit and, within the framework of a commentary on the first treatise of the Palestinian Talmud, to present a novel approach to the study of this literature.

To the initiated with the Yerushalmi’s commentaries I think a tenable argument can be made that Ginzberg’s tomes are a unique attempt at approaching the study of Talmud Yerushalmi with modern methods through the very framework he delineated in his introductions. Alas, R. Zimmerman did not offer examples to the contrary, i.e. books predating Ginzberg which approached the Yerushalmi mirroring the latter’s methods. This is in stark contrast to Solomon Zeitlin’s perspective who wrote in his review of the Commentary: “It is the first and only serious rabbinic work published so far in this country. Ginzberg is the first to give us a thorough, scholarly treatment of the Palestinian Talmud from the old rabbinic and also scholarly point of view.” Zeitlin, not being one to ingratiate with embellishment, went so far to suggest “Solomon ibn Adret said there was only one in a generation who could understand the Palestinian Talmud. Prof. Ginzberg, I believe without exaggeration, has no equal in our generation and is one of the greatest authorities on the Palestinian Talmud since the time of the Gaon of Vilna.”[2] Among the many Roshe Yeshivot and rabbanim who respectfully referred to and/or corresponded with Ginzberg, mention should be made here of what R. Mordechai Gifter wrote to Ginzberg upon receiving a copy of the Commentary

זה כשבוע שהובא אוצר גדול לביתי הוא ספרו של כבודו “פירושים וחידושים בירושלמי”, ואתמול גמרתי העיון בכרך הראשון על שני פרקים הראשונים במס’ ברכות. ואף שאין כבודו צריך לדכוותי, לא אוכל להתאפק לומר לו “יישר חילו לאורייתא”, ואקוה שיזכה להו”ל ספרו על כל הירושלמי, להאיר עיני ההוגים בתלמוד זה. הספר גזל ממני הרבה שינה, ואקוה שיהיו לרצון לפניו הערות אחדות שמצאתי להעיר בדבריו[3]

P. 132

R. Zimmerman introduced the question regarding the strength of the obligation to recite the paragraphs of the Shema section; is it Biblical or rabbinical and, if any, which paragraphs? He called attention to the Peri Chadash and Sha’agas Aryeh who offered their respective

“great pilpulim… The Sha’gas Aryeh in his great teshuvah [responsum] has a pilpul on the subject, where he quotes some pieces of the Peri Chadash and argues against them… Ginzberg writes in a very trivial and casual tone against these two renowned geonim… Ginzberg writes that these two geonim, despite all their lengthy pilpul, overlooked an explicit and open source in the Talmud Yerushalmi.”

Not only is this an overly exaggerated characterization of Ginzberg’s actual words, the irony is eyebrow raising as Ginzberg’s words are presented in the footnote and the readers can detect this themselves, save for the note which contains a truncated text of Peri Chadash and therefore gives a different impression of what Peri Chadash actually wrote and how he formulated his discussion. These are Ginzberg’s words [with emphasis on the phrasing under attack]:

האחרונים האריכו לפלפל אם למ”ד ק”ש מן התורה ב’ פרשיות הן מן התורה או רק פרשה ראשונה (עיין פרי חדש ס”ו [ע.ה.: צ”ל ס”ז], ושאגת אריה ס’, ב’) ולא העירו על דברי הירושלמי כאן, שכבר אמרנו בכמה מקומות שלהירושלמי ק”ש מן התורה, ומ”מ טרחו למצוא טעם למה אין צריך כוונה רק פרק ראשון ולא אמרו שפרק ראשון מן התורה ולכך צריך כוונה ופרק שני מדרבנן ולכן אינו צריך כוונה, וע”כ ששניהם מן התורה, ועיין ראש דבור הקודם, ואכמ”ל

First of all, such common stock phrases, in all of rabbinic literature, needs no elaboration other than to say that it is not perceived as an undermining and disdainful “very trivial and casual tone” (never mind the harsher verbiage, and no less from R. Hezkiah de Silva himself).

After repeating this same stricture (p. 133) R. Zimmerman adds:

…it is astonishing that the academic “scientific scholar” Louis Ginzberg either did not understand the words of the Peri Chadash and Sha’agas Aryeh, or deliberately deceived to discredit them. The error of Ginzberg here is because in the same chapter of the Peri Chadash, the Peri Chadash himself quotes this Talmud Yerushalmi, and brings this very proof with respect to which Ginzberg claims that he “caught” the Peri Chadash and the Sha’agas Aryeh in overlooking the Talmud Yerushalmi. Of course, the Sha’agas Aryeh makes reference to the Peri Chadash, so obviously he does not have to repeat the proof from this Yerushalmi which is clearly stated by the Peri Chadash.

Let us inspect the Peri Chadash. He begins chapter 67 with a thorough exposition determining what the obligatory status is with regards to reading chapters of the Shema. After about eight long paragraphs he arrives at his own conclusion that the reading of both chapters are biblically mandated and suggests that Rambam’s words appear to evoke the same opinion. He writes:

מעתה נשאר לנו לברר הדעת השלישי’ והיא היותר אמיתי מכולן דפרש’ שמע ופרשת והיה אם שמוע השתי פרשיו’ הוו מן התור’… וכך מטין דברי הרמב”ם ז”ל… וזו היא דעתי ומסתייעא הדין סברא דילן מהא דגרסינן בפ’ היה קורא…

Moving on to a dissection of the respective topic in the Bavli in order to prove his opinion, Peri Chadash qualifies that there is a Tanaitic dispute if the reading of both also require intent (“kavannah”) or only one of the chapters and adduces support from a Tosefta, interpreting the two opinions to be debating this last question vis-à-vis intent. To further corroborate this interpretation Peri Chadash finally adds:

ובירושלמי אמרינן מה בין פ’ ראשון דבעי כוונ’ לפ’ שני דלא בעי כוונ’ ומשני לה, נמצא דהני תנאי ס”ל דשתי פרשיו’ ראשונו’ הוו מן התור’…

It seems it is quite reasonable, if not absolute, to understand Peri Chadash’s usage of the Yerushalmi only as support to his interpretation of the views in the Tosefta regarding intent as it relates to “דהני תנאי” of the Tosefta. In other words, Peri Chadash did not cite the Yerushalmi in order to settle the question regarding the status of the Shema passages. One would imagine that if it was his intention do so he would have introduced such a critical source much earlier in his discussion and devoted more than a brief quote of this Yerushalmi passage. It appears that Sha’agas Aryeh too understood the Peri Chadash in this vein since, in his responsum, he does not merely “make(s) reference to the Peri Chadash” – he systematically went through Peri Chadash’s proofs and refutes them one by one, yet he does not single out the Yerushalmi in attempt to disprove the proof from it.

PP. 134

Before moving to this example it is important to present the relevant rabbinic materials. Briefly put, the Yerushalmi presents two opinions as to why one must have his feet together when praying. One of the two opinions learns this from the exegetical requirement of the Kohanim to walk heel-beside-toe (“עקב בצד גודל”). A mishnah in Yoma (2:1) tells us that prior to certain Temple regulations Kohanim would race up the ramp in order to merit doing a particular service. The Tosefos Yeshanim (Yoma 22a s.v. bezman) points to this contradiction; namely, how were the Kohanim permitted to run if it is indicated in the Yerushalmi that the Kohanim were required to walk heel-beside-toe? Dismissing the possibility that they ran heel-beside-toe (“ואין נראה לומר דרצין עקב בצד גודל קאמר”) Tosefos Yeshanim goes on to present what appears as two answers. Answer 1: “ושמא כיון שלא [היו] עדיין עסוקין בעבודה כמו בהולכת אברים לכבש יכולין לרוץ” (= since they had not yet been involved in a service, such as the delivering of the limbs via the ramp, they were allowed to run). Answer 2: “אי נמי רצין עקב בצד גודל שלא להראות כמו עושה כן אלא כי כן צריך לו לילך בשעת עבודה כדפי’”. One readily discerns that this reading is textually defective. On the margin of this folio in the standard Vilna edition, a gloss is brought closing with “וע’ ש”י” (= see Siah Yitzchak [Nunes Vaes, Jerusalem 1960, p. 293]), presenting a substantiated alternative reading which, for the sake of brevity, I will not get into other than to point out that the alternative phrase indicates that there is no second answer. Instead, the rest of the text is a further explanation of a particular, related Talmudic passage elsewhere. On the other hand, in R. Avigdor Arieli’s edition of the Tosefos Yeshanim (Jerusalem 1993, p.30) some text of Tosefos HaRosh is incorporated and such is the text given: “אי נמי רצין עקב בצד גודל [קאמר שהיו ממהרין ללכת בענין זה…]”. This answer seems to say that the Kohanim would hurriedly walk heel-beside-toe. The nuanced difference borne in this answer compels one to consider that Siah Yitzchak’s emendation is more likely.

This now brings us to the commentary of R. Avraham Abba Schiff in his To’afos Re’em which R. Zimmerman uses to level charges against Ginzberg. Here is the pertinent text of R. Schiff:

…ובירושלמי… אמרו זהו שעומד ומתפלל צריך להשוות את רגליו כו’ ח”א כמלאכים וח”א ככהנים כו’ שהיו מהלכים עקב בצד גודל וגודל בצד עקב משמע משם דוקא וכ”כ התוס’ ישנים יומא שם עיי”ש שכ’ אי נמי רצין עקב בצד גודל שלא להראות כחו עושה כן אלא כי כן צריך לו לילך בשעת עבודה כדפי’ עכ”ל ודבריהם אלו אינם מובנים והנראה לי דט”ס יש שם וכנ”ל אי נמי רצין ועולין בכבש עקב כו’ ור”ל דמתני’ ה”ק היו רצין עד לכבש והולכין בכבש כדרכן עקב בצד גודל וזהו שסיימו בת”י שלא להראות כחו עושה כן כו’ פי’ במ”ש ועולין בכבש לא להראות כחן היו עולין לכבש דעולין בכבש כדרכן עקב בצד גודל אלא עיקר הקדמתן במ”ש היו רצין דהיינו עד לכבש…

R. Schiff likewise noted the textual difficulty of the Tosefos Yeshanim and therefore suggested a different reading. He proposed that the second answer means (reads) the Kohanim would run up until the ramp but from there they would walk heel-beside-toe. If this is the second answer it seems somewhat forced as its underlying rationale is presumably to restrict running when ascending the ramp, i.e. executing a designated service, and it is essentially the same as the first answer.

Returning to R. Zimmerman, after he informs us of the aforementioned Tanaitic contradiction, he continues:

Tosefos Yeshanim… gives these two terutzim [solutions] to answer this contradiction. On the Sefer Yere’im… there is a perush [commentary] by the name To’afos Re’em where he brings all the bekiyus [referecnes] on this subject. He also writes this contradiction and explains both terutzim. And after he writes these two terutzim, he references the Tosefos Yeshanim, as quoted above.

Next, R. Zimmerman asserts that:

…with the claim of originality, Ginzberg answers the contradiction asked by the Rishonim and of Tosefos Yeshanim with these two solutions, not being aware that Tosefos Yeshanim himself wrote these two answers word for word.

Here too, Ginzberg’s text is presented and the reader can see that he nowhere asserts any claim of originality. He merely referenced the classic sources, including the Tosefos Yeshanim, and then paraphrased what some of the Rishonim asked and answered. The only phrase one can guess (or, read into) which R. Zimmerman based this imputation is where Ginzberg wrote, regarding the distinction of ascending the ramp when executing an actual part of the service, “והיה אפשר לומר”. But, this is borderline pedantic as any accustomed student of rabbinics does not expect an author to reiterate every time they allude to an aforementioned source. He essentially claimed that Ginzberg quoted the sources but “did not make the effort to look up the Tosefos Yeshanim, and he plagiarized the words of the To’afos Re’em… taking credit for himself, and taking for granted that no one will catch him in plagiarizing these two big “chiddushim” word for word from the To’afos Re’em.” By that token one must assume as well that the other sources which Ginzberg quoted and dealt with were also gotten from a different (albeit, unnamed) source. More importantly, it is not entirely clear that To’afos Re’em even spelled out both answers of Tosefos Yeshanim, precluding the possibility that Ginzberg plagiarized “word for word from the To’afos Re’em”. Never mind the strange notion that Ginzberg wouldn’t look up an explicit Tosefos Yeshanim which he cited and instead opted to quote an unclear formulation of the To’afos Re’em.

(The reference in p. 135 n. 279 to the Commentary should read: ‘עמוד 45’, and “שהרי על הלכה כהנים זו” should read ‘…הלכת כהנים זו’. For “keves” on p. 134, “keveṣ” or “kevesh” should be supplied.)

PP. 136

R. Zimmerman opined that with all the reference books on the Yerushalmi et al.

…if someone has in front of him all these sefarim when he learns Talmud Yerushalmi (he does not have to be an expert in Halachah), he could produce most of Ginzberg’s works.

Leaving aside this fantastic assumption and the certain debatable quality of the older reference books, one wonders if the careful inclusion of “most” was some admission that even with all reference books at one’s disposal, Ginzberg’s monumental ‘Legends of the Jews’, however, could certainly not have been produced by just anyone, not even today with our advanced digital databases. If this assumption is correct, one wonders how to reconcile the acknowledgment of Ginzberg’s singular erudition but then to accuse him of plagiarizing even known, classical sources.

PP. 137

R. Zimmerman gave some examples to illustrate Ginzberg’s dependency on the various reference books and in particular Rabbi Dov Ber Ratner’s ‘Ahavas Tzion vi-Yerushalayim’ of which he alleges:

Ginzberg being aware that one may discover the obvious, that most of his references and citations are plagiarized from Ratner… and others, always tries to disqualify Ratner and others.[4]

I’m going to leave aside the obvious question as to the merit of such a claim, whether or not an author should always cite a reference book at every instance. Instead, I prefer to determine if there is any basis at all to the claim of deceit.

The first example of Ginzberg’s alleged attempt to disqualify Ratner’s work is R. Zimmerman’s oblique citation to the English introduction of the Commentary. Here are Ginzberg’s actual words:

The most important source for establishing a correct text are the numerous quotations… and one must be grateful to Baer Ratner (1852-1917) for collecting them in twelve volumes of his work… The parallels must however be used with great caution for the following reasons…

Ginzberg then continued to list three sound and ostensibly true critiques and words of caution.[5] Perhaps interpretation is in the eyes of the reader so suffice it to say there is no readily discernible attempt to “disqualify Ratner’s work”. Conversely, in Ginzberg’s Seride Yerushalmi, after he described the importance of collecting and collating quotes of Yerushalmi as found in Rishonim, he stated “וכבר התחיל במצוה הרב הגדול וכו’ כמוה”ר בער ראטנער נ”י בספרו יקר הערך ורב השבח ספר “אהבת ציון וירושלים” אשר בו העיר על גרסאות הירושלמי שבספרי הראשונים והאיר עיני לומר הירושלמי.”” (New York 1909, intro. IV). Such statements would be counterproductive and ineffective if attempting to disqualify a work.

IBID

He copies from Ratner verbatim without mentioning his name.

The reference is given to Commentary p. 54 where Ginzberg indeed quoted the same two passages from the Yalkut which Ratner quoted. Now, even before analyzing the material one must wonder if two authors cite the same classical and relevant sources is that sufficient to presume one copied from the other?[6] In any case, if one reads the detailed discussion of Ginzberg it is unmistakable that he independently studied and scrutinized the sources for he included much detail of which Ratner does not give the slightest mention. Furthermore, mention should be made of the fact that the referenced volume of Ratner was published in 1901 and the first volume of Ginzberg’s ‘Legends’, a work which had begun in 1903 was published in 1909 (JPS 2003[7], intro. XVI). There, in describing the distance between earth and heaven (the focus of the aforementioned Yalkut) Ginzberg referenced the Yerushalmi under discussion in addition to numerous other sources (ibid. p. 10 n. 31 & 32). Interestingly, he did not, however, cite the Yalkut which he later cited in his Commentary. With intent to minimize Ginzberg’s scholarship we can fault him for not referencing the Yalkut in the notes to his ‘Legends’. But, an obvious explanation can be, due to the enormous and difficult task in reworking all available ancient texts and incorporating them into a flowing narrative by necessity would require paraphrasing and omitting subtle Aggadic amplifications. The passage in the Yalkut, which Ginzberg expresses doubts per its original text, contains almost identical phrasing as the Yerushalmi and therefore added nothing for his sources. Had Ginzberg only known about the Yalkut passages from Ratner he should have referenced it in his ‘Legends’. This is, again, leaving aside the perplexing claim that someone who organized and authored the intricate, colossal and scholarly sources and discussions in the notes to the ‘Legends’ did not independently know the Yalkut, a primary text quoted throughout the ‘Legends’.

IBID

…he writes “many erred” because they did not know the sources, but the sources are written by Ratner…

Ginzberg commented that a particular passage of the Yerushalmi is found similarly in the Bavli, and while some Rishonim/Geonim quote the passage as it’s reflected in the Yerushalmi Ginzberg posited that their source was from the Bavli, unlike Ratner who quoted the parallels in the Sheëltot and BH”G and determined that their source was the Yerushalmi. Ginzberg concluded the brief comment by exclaiming

וטעו אלה שאמרו שבה“ג והשאלתות השתמשו כאן בירושלמי, עיין מה שכתבתי גואניקא א’, פד.

Ginzberg clearly was taking issue with what some erroneously assumed that the Yerushalmi was the common source for those two authorities, not that some did not know the sources. Besides for his objection being rather clear, when one examines the reference to Geonica they are met with a more detailed analysis of this error. As if it’s not explicit enough, there Ginzberg wrote:

“In his learned scholia… Ratner does not hesitate to attribute it to the Yerushalmi as Rabbi Aha’s source, and yet it can be readily demonstrated, from the words of the Sheëltot, that it goes back to the Babli.”

P.138

Again, Ginzberg writes ‘Ratner did not indicate this source’, and this is an outright falsification, because in that same place Ratner quoted the source.

The reference here is to Commentary (p. 75 fn. 84). Ginzberg writes

לאוהבו של מלך שבא והרתיק על פתחו של מלך. במחזור ויטרי שי”ג (וראטנער לא העיר על מקור זה) גרס, תערו במקום פתחו, וזה יותר מדויק…

In the parenthesis, after “מקור זה”, a footnote reads

וכן לא העיר על הילקוט… אשכול… ושלחן ארבע שמביאים דברי הירושלמי על התכיפות

R. Zimmerman must have been referring to the Yalkut reference since Ratner (cited by R. Zimmerman) does not refer to Mahzor Vitri, Eshkol or Shulhan Shel Arba. Yet, even the Yalkut is only cited by Ratner on the preceding piece of Yerushalmi “מי שתוכף לסמיכה שחיטה”. On the piece under discussion, indicated by the caption of Ginzberg’s quote, Ratner only makes reference to the Amsterdam ed. of the Yerushalmi and did not note the textual variants contained in the Yalkut. Aside for this not being “an outright falsification”, the language used to quote Ginzberg is misleading. R. Zimmerman specifically referred to the footnote in Commentary, though it does not say there “Ratner did not indicate this source”; that exact phrasing is in the main text regarding the Mahzor Vitry which Ratner did not reference. The footnote says (if rendered in English) “he also did not indicate A, B and C.” If one were to object that A was indeed indicated by Ratner then a fairer phrasing would be something to the effect of “one of the sources was quoted by Ratner” thereby not wholly discrediting the author’s point.

At this junction I’d like to refer to one piece produced in the Hebrew section (p. 211) as it directly relates to this piece. Ginzberg’s aforementioned text is quoted and then R. Zimmerman notes

מ”ש “במחזור ויטרי שי”ג גרס תערו במקום פתחו” לא היה ולא נברא. וזה לשונו [במחזור וויטרי] סימן י”ז [עמוד 13] א”ר חמי של מי שאינו סומך גאולה לתפלה למה הוא דומה לאוהבו של מלך שבא והרתיק על פתחו של מלך… וכו’. ואמנם הגירסא זו [תרעו ולא כמ”ש גינזבורג תערו] הובא בספר המנהיג [דיני תפלה, עמוד מ”ד, הוצאת מוסד הרב קוק] וכבר ציינה ראטנער [אהבת ציון וירושלים, צד 11] וזה המחבר זייף דברי ראטנער כדרכו. ואמנם כך פירשו שמה המחזור וויטרי, תרפ”ד, דף 31, כמו שציין גינזבורג אלא שהרי המחזור וויטרי סותר את עצמו…

Admittedly I’m unsure what to make of this protest. R. Zimmerman unabashedly quotes a second text from Mahzor Vitry, which Ginzberg was explicitly not referring to, and then impugns Ginzberg of quoting a spurious text from Mahzor Vitry (and plagiarizing from Ratner), despite R. Zimmerman’s subsequent acknowledgment that Mahzor Vitry does elsewhere contain the very text quoted by Ginzberg. Additionally, the bracketed words, which dismiss Ginzberg’s quote of “תערו”, are also disingenuous since Ginzberg was not referencing the Manhig’s text at all. This also brings us back to my earlier suspicion of the editor’s methods: Who inserted these erroneous brackets? Was R. Zimmerman being unfair or was the editor unmindful?

In summation, a pattern emerges before the reader which betrays a vendetta against Ginzberg; picayune criticisms and inflated accusations which don’t hold much water. Any time a reference provided by Ginzberg had been cited elsewhere it is automatically assumed to be stolen and any explanation offered is deemed unlearned, unless there is precedence to it then it is assumed to be plagiarized. It appears it was Ginzberg himself who was the object of R. Zimmerman’s attacks, while grasping at straws under the pretense of a scholarly critique. One cannot but wonder why R. Zimmerman did not publish these galleys while Ginzberg was alive, affording him the opportunity to respond. It is not as if R. Zimmerman was one to shy from polemicizing, as he famously engaged with R. Menachem M. Kasher over the International Date Line matter. Had R. Zimmerman published the materials while Ginzberg was still alive perhaps he, and its current readership, would have merited the author’s own rebuttal.[8]

___________