Using the works of Shadal and R. N. H. Wessely

Using the works of Shadal and R. N. H. Wessely

By Eliezer Brodt

This post is a continuation of my review of Rabbi Posen’s Parshegen, here. Many thanks to S. of On the Main Line for help with certain points.

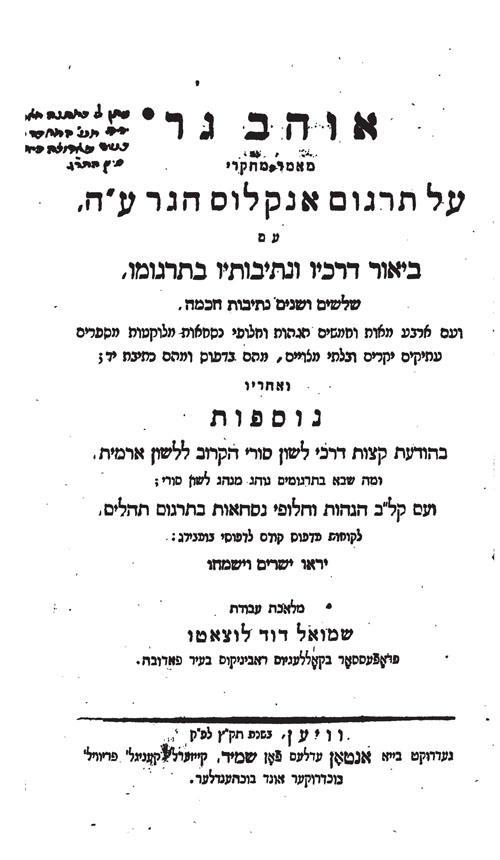

In the beginning of Parshegen, when listing the important works on Targum Onkelos (TO), Rabbi Posen notes that one of the most crucial works ever written on the topic is Shadal’s Ohev Ger (Vienna 1830; rpt. Cracow 1895). He mentions in a footnote that today most Charedi works on TO do not use him, or do not mention it if they did. He notes that in the first generations after Shadal wrote Ohev Ger everyone used it. He refers his article in Italia 19, (2009) (pp. 104-109) on the topic of Shadal as a Parshan of the Targum, where he has a few pages dealing with Charedi works that use him, including the Minchas Yitzchak. Posen notes that the Maharatz Chajes quotes him respectfully, but what is important about this is that the Maharatz Chajes did not see eye to eye with Shadal on other issues[1] and even wrote an essay attacking his criticisms of the Rambam (link). Posen notes that R. D.Z. Hoffman uses him in his Shu”t Melamed Le–hoel. I would add (something Posen is certainly well aware of) that R. Hoffman also uses him many times in his works on Chumash[2].

I would like to add a few more names toRabbi Posen’s list of people who used Shadal. Shoel Umeshiv[3], R. Yosef Zechariah Stern[4], R. Pesach Finfer[5], Dikdukei Sofrim[6], Seridei Eish[7], R. Chaim Heller[8], R. Kalman Kahana[9], R. Wolf Leiter[10] andR Dovid Tzvi Hillman[11]. S. of On the Main Line informs me that he has many more such references and is working on an extensive piece about Shadal in the eyes of talmidei chachomim through the ages.

I also found in the list of works recommended by the great Galician posek R. Meshulam Roth for students to learn in a proposed new school system, at the request ofR. Meir Shapiro, among the many interesting things he wanted talmidim to read when learning Targum Onkelos was Ohev Ger.[12]

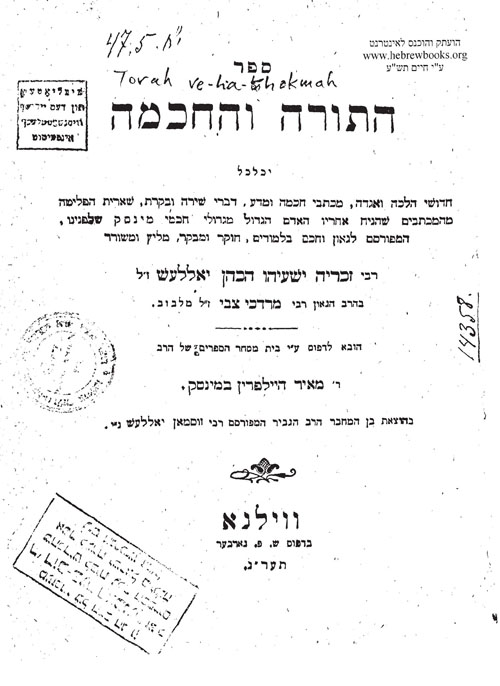

When talking about this topic of the usage of Shadal in Charedi and Charedi-acceptable circles, Posen cites the introduction of Rabbi Yaakov Zvi Mecklenburg (1785-1865) to his Ha-Kesav Ve-ha-Kabbalah, printed only in the first edition of the work in 1839[13]. In this introduction he quotes a lengthy letter from Shadal[14] and clearly mentions that one of the works that he used when writing his sefer was from Shadal (which we would know anyway, because Shadal is cited by name many times in the commentary). Posen points out that in all subsequent editions this introduction has been removed. Posen suggests that the son-in-law who reprinted this work after he died (1880) removed it, and perhaps he did so due to the list of people that he used, especially theway he refers to Shadal, perhaps then no longer politically correct. Now, to be a little more accurate, the second edition of the work was printed in 1852 while Rabbi Mecklenburg was quite alive, and there a different version of the introduction appears. In this shorter version of the introduction it includes some of the works he used but there is no longer a specific mention of Shadal, neither in regard to using his work, or the lengthy letter of Shadal, which is now missing. In all subsequent editions printed after he died no introduction was printed. Thus we can see the son-in-law had nothing to do with it, but since it could hardly have been coincidental perhaps it did have to with Shadal’s image in some way, as Posen suggests. In his excellent article on the topic[15] Edward Breuer points out that there were differences between the two introductions, but he only notes that Julius Fuerst, whose name was mentioned in the first version of the introduction, was removed in the second version. Breuer did not note that Shadal’s name was also omitted.

Compare the introductions:

Mecklenburg – Haksav vehakabbalah 1839

Mecklenburg – Haksav vehakabbalah 1852

Since many of the controversial aspects of Shadal’s intellectual profile where already well-known by 1839 (e.g., proposing textual emendations of Nakh, fierce criticisms of the Rambam, assigning an author other than Shlomo to Koheles, etc.)[15b] my tentative suggestion as to why Shadal’s name and his letter were omitted by Rabbi Mecklenburg in the second edition could be because 1852 saw the printing of Shadal’s anti-Kabbalah work, the Vikuach Al Chochmas Ha- Kabbalah[16] (subtitled al Kadmus Sefer Ha-zohar). In addition, perhaps the advent of this work explains why later many did not use Ohev Ger on TO, feeling that they could not quote someone who was so anti-Zohar and anti-Kabbalah, even where he is not problematic and writes worthy ideas.

In Matzav Hayashar, R. Shneur Duber after quoting from Shadal’s work Vikuach Al Chochmas Ha- Kabbalah writes:

וה’ שד”ל בספרו ויכוח על חכמת הקבלה… וכל אלו הספרים הנההיראים החרדים לדבר ה’ נזהרים מאוד מלאחזיקם בביתם ומכש”כ מלעיין בהם משוםשהמה מהפכים את הלב האדם הקורא בהם ועושים רושם גמור בלבו רק לי התירו כמה גדולירבנים גדולים משום דאיתא במסכת אבות (פ”ב משנה יד) ודע מה שתשיב…”(מצבהישר, ב עמ’ 66].

It is also possible that R. Yaakov Kamenetsky was referring to the Vikuach in a sort of hidden way in Emes Leyaakov (p. 399). R. Yaakov records that he was asked by someone why is the Yom Tov of Hoshana Rabbah hidden and only found in Kabbalah literature? Before giving an answer R. Yaakov remarks he suspected there was a bit of cynicism in this question against the Zohar. It could be that he was hinting to the opening debate (before it spring boards in to other topics) in Shadal’s Vikuach Al Chochmas Ha-Kabbalah which takes place on Hoshana Rabbah and it is about where is the source for this Yom Tov.[17]

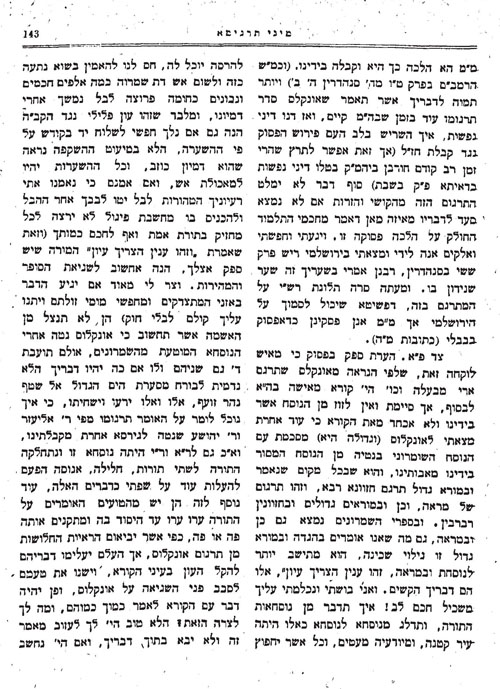

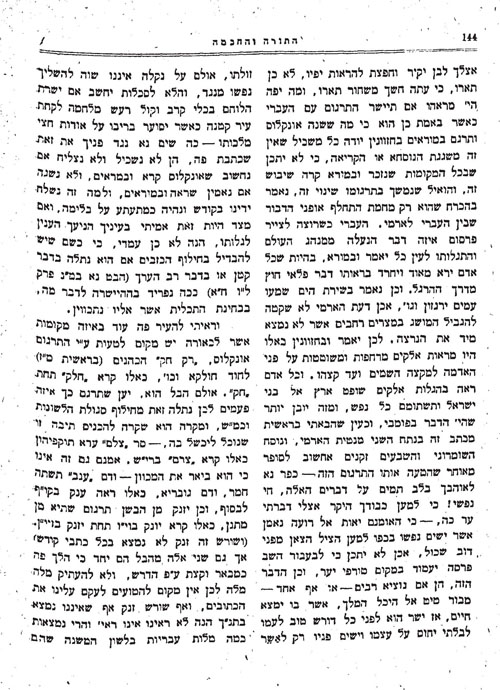

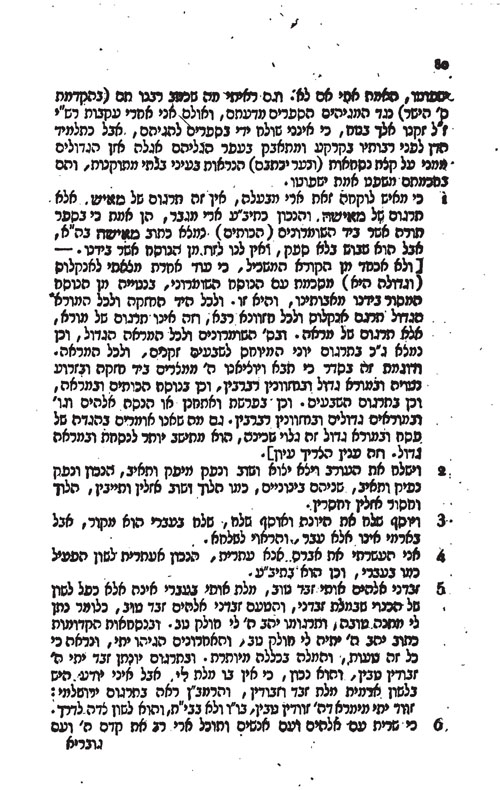

Another possible explanation as to why many did not use the works of Shadal could be understood with the complaints of R. Z. Y. Yolles in Hatorah VeHachochma. R Z. Y. Yolles sent Shadal a nice long letter related to TO in general and some comments on the Ohev Ger[18] in particular, which he liked a lot. He then writes:

ואין לזוז מן הנוסח אשר בידינו… כי עוד אחרת מצאתי לאונקלוס…מסכמת עם הנוסח השומרוני בנטיה מן הנוסח המסור בידינו מאבותינו,… וזהו ענין הצריך עיון… אלו הם דבריך הקשים [19],ואני בושתי ונכלמתי עליך משכיל חכם לב איך תדבר מן נוסחאות התורה, ותדלג מנוסח אל נוסחא כאלו היתה עיר קטנה, ומיודעיה מעטים וכל אשר יחפוץ להרסה יוכל לה, חס לנול האמין בשוא נתעה כזה ולשום אש דת שמרוה כמה אלפים חכמים ונבונים כחומה פרוצה לבל נמשך אחר דמינו, ומלבד שזהו עון פליפי נגד הקב”ה הנה גם אם נלך חפשי לשלוח יד בקודש על פי ההשערה, הלא במיעוט השקפה נראה שהוא דמיון כוזב, וכל ההשערות יהיו למאכולת אש, ואם אמנם כי נאמנו אתי רעיוניך הטהורות לבל יטו לבבך אחר ההבל ולהכניס בומחשבת פיגול… וזאת שאמרת וזהו ענין הצריך עיון המורה שיש ספק אצלך הנה אחשוב לשגיאת הסופר והמהירות וצרי לי מאוד אם יגיע הדבר באזני המתצדים ומחפשי מומי זולתם ויתנו עליך קולם לבלי חוק… הלא טוב הי’ לך לעזוב מאמר זה ולא יבא בתוך דבריך…

Here are Yolles and Shadal:

Here is the page from Ohev Ger with which the letter is concerned:

Although Shadal was very opposed to changing any texts in the Torah[20] and in a sense could be seen as standing in the breech, it could be that even such comments scared people away from his works.

Returning to the introduction of Rabbi Yaakov Mecklenburg to his Ha-Kesav Ve-ha-Kabbalah; It is of interest to me how he refers to R. Naftali Hirz Wessely (Weisel). He not only includes Wessely in the list of works he used, but in thebeginning of the introduction he says that Wessely is the only good work on Toras Kohanim which ties Torah Shebekhesav to Torah Shebaal Peh. This piece is also not found in the second edition of the introduction and is not noted by Breuer in his aforementioned article. A careful reading of the Ha-KesavVe-ha-Kabbalah shows that he used Wessely’s work numerous times throughout the work. Naturally no new views of Wessely’s were revealed between 1839 and 1852 to make Wessely more controversial.

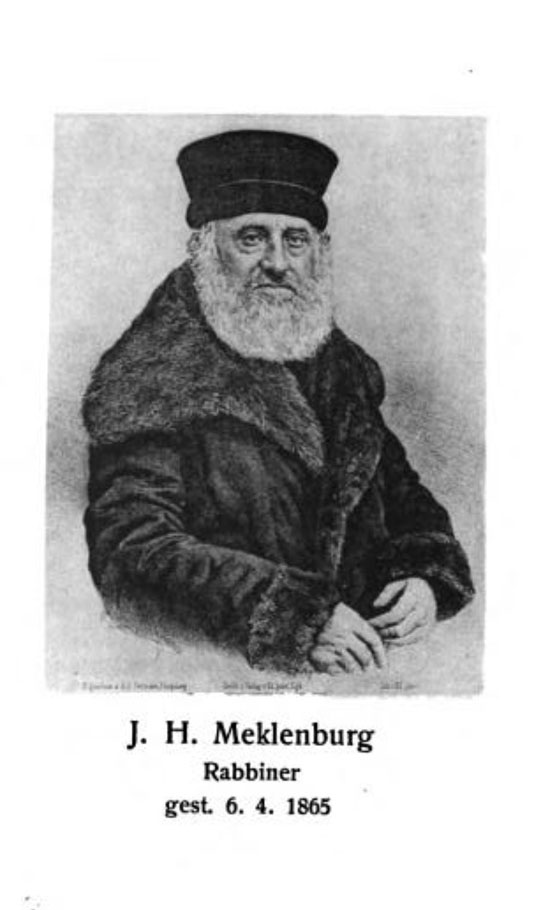

Incidentally, here is a beautiful portrait of R. Mecklenburg as printed in the Festschrift zum 200 jährigen Bestehen des israelitischen Vereins für Königsberg (1904):

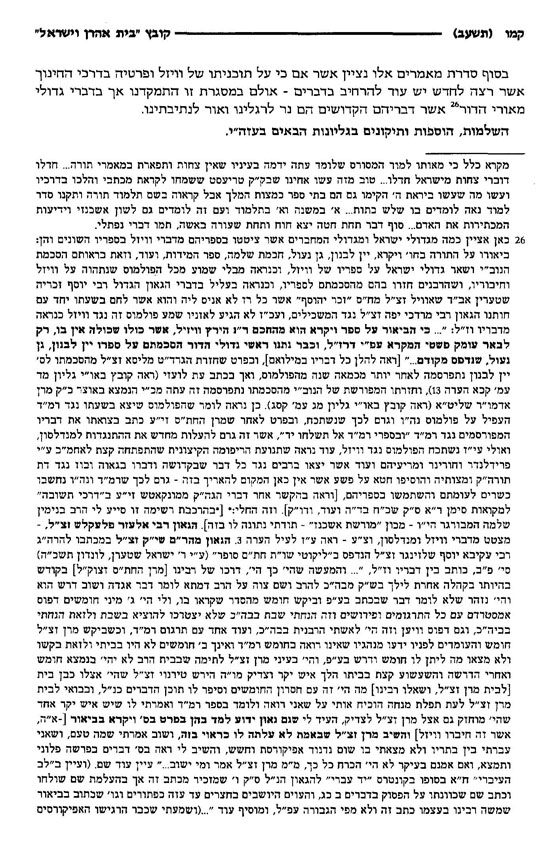

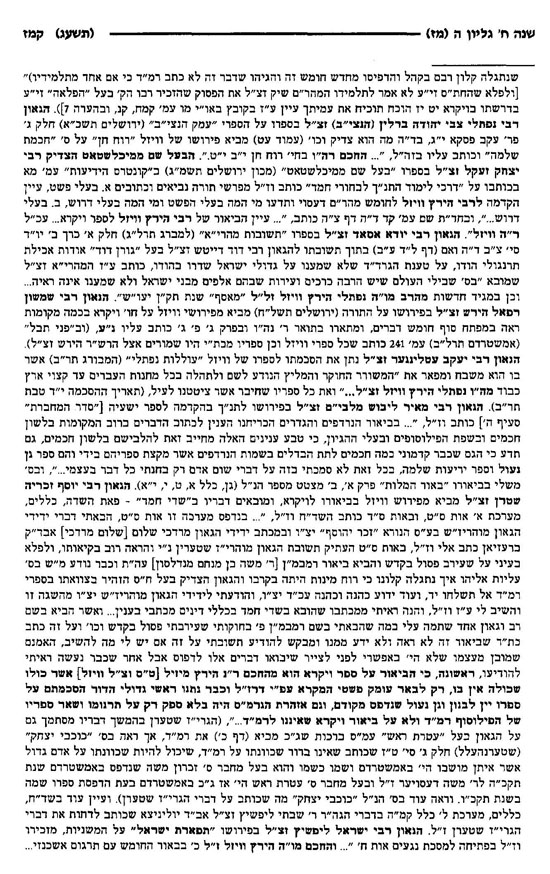

A few years ago in the pages of the excellent journal Ha-maayan, a controversy took place in relation to how to cite various works of people considered questionable (here). In the course of the controversy it turned to quoting Mendelssohn and Wessely, and their stories. Rabbi Posen mentioned that there was nothing wrong with Wessely, to which others argued. This controversy in regard to Wessely was not a new one[21], a few years before in the Kovetz Beis Aharon VeYisroel there was a series of articles based on various manuscripts showing how the gedolim at the time were very against Wessely. Towards the end of the series the author did a strange thing – he collected many citations of big name gedolim who did use Wessely’s work even after the controversy (here). Almost all of these gedolim were well aware of the controversy over Wessely’s Divrei Shalom ve-Emes in which his maskilic program for educational reform was outlined, and they came after the outcry of those early gedolim. So obviously disagreed with them (or were at least willing to accept him as a source to be used and cited by name). To me this was strange, as he undermined his own research – he wound up showing that there was a big controversy with many big people on both sides, so how in the world did he reach his conclusion that Wessely was bad according to everyone? Also of note, י”שר appears after Wessely’s name only in the first piece in the series. Perhaps in the course of his research the author realized that te matter was not as black-and-white as it first seemed.[22]

Nor did the modern controversy about Wessely end there, as a few years later two works of Wessely’s were reprinted; his Sefer Hammidos (2002), and his Yeyn Levanon (2003). In the introduction of both works there are lists of great people who used Wessely’s works. To be sure the kannoim did not remain quiet about this. That same year (2003) in the introduction to the Tomer Devorah reprinted by the Mishar publishing house, an introduction was printed about the evil works of Wessely recently reprinted. A few months ago the Kovetz Eitz Chaim (15, 2011, pp. 13-30) printed another manuscript on the controversy against Wessely, including some letters of various contemporary gedolim against the evil Wessely. In the recent work on R. Elyashiv Shlita, Hashakdan (2, pp. 136-137) they also mention how he was against the reprinting of the works of Wessely. The problem to me is how do they explain all the great Gedolim who did use his works? There is no clear answer.

To add to the lists of Gedolim who used Wessely’s works or quoted him in a positive light see; R. Eleazer Fleckeles[23], R.Moshe Kramer[24], Netziv[25], R. Mordechai Gimpel Yaffe[26], R. Yosef Zechariah Stern[27], R. Eliyahu Feivelson[28], R. Ezriel Hildsheimer[29], Dikdukei Sofrim[30], R. Y. Haberman[31], R. Chaim Bachrach[32], R. Y. Heller[33], R. Shneur Duber[34], R. Lazer Gordon[35], and R. Dovid Tzvi Hoffman[36]. Also see R. Moshe Mendelssohn (a maternal uncle of R Hirsch)[37] for many interesting remarks on Wessely. See also these great posts here and here in regard to Wessley.

I am sure many more sources for usages of both Shadal and Wessley can be found by searching Google Books, Hebrew Books and Otzar Hachochmah and just plain old learning, but I did not have a chance to do that yet.

I would liketo conclude with the following dream: just as R. Shlomo Dubno was vindicated in the past few years by R. Dovid Kamentsky,[38] it is my hope that Wessely too will be vindicated from all false charges against him and people will realize there is nothing wrong with his fine writings which are filled with chochma and yirah.

[1] See M. Hershkowitz, Maharatz Chajes,pp. 314-323. See also R. Toresh, Shivah Kochevei Leches, p. 8. Of course it will be argued that he is controversial too. However, this is only the case in some Torah circles. Where he is considered a perfectly reputable talmid chochom his use of Shadal could be considered notable.

[2] e.g., in Bereshis, p. 132. Shemos, p.287, 290, 351, 355. In Chumash Vayikra in his introduction he writes: הערות מצוינות אשפר למצוא… ובהמשתדל לש. ד. לוצטו.

[3] See Shem Me-shimon, (1965), p. 29, where it is related that he had a question related to Hilchos Gittin and he borrowed Shadal’s work on targum to help him. See M. Hershkowitz, MaharatzChajes, p. 445.

[4] Haggadah Shel Pesach, p. 7a.

[5] Mesoras Hatorah Vehaneviyim, p.6, 8, 14, 40, 42, 64.

[6] See his notes to Shem Hagedolim, (Yeshurun 23, p. 240, 289.) A look at the list of his working library in Ohel Avraham shows that he had all his seforim in this collection, including his work Vikuach Al Chochmas Ha- Kabbalah. The library belonged to his patron Abraham Merzbacher, but in many letters he refers to it as his library.

Dikdukei Sofrim quotes Shadal in Maamar al Hadfasas Ha-talmud p. 42 and numerous other places . He usually calls him רשד”ל. See this recent amazing post at On the Main Line for some general stuff about the Dikdukei Sofrim.

Dikdukei Sofrim quotes Shadal in Maamar al Hadfasas Ha-talmud p. 42 and numerous other places . He usually calls him רשד”ל. See this recent amazing post at On the Main Line for some general stuff about the Dikdukei Sofrim.

[7] Mechkarim Betalmud, p. 51, 60. See also Kesvei Sredei Eish 2, p. 323.

[8] Al Targum Yerushalmi, p. 36; Al Targum Hashivim, p. 36.

[9] Cheker Veiyun, p. 142. This is an incredible piece where he deals with a piece of R. Menashe Me-Ilya has on how to translate the wordהרעי where he says an original pshat that the Shoel Umeshiv attacks. See also M. Hershkowitz, Maharatz Chajes, pp. 449-451.

[10] Me-Torason Shel Rishonim, (p.102). [This is in regard to the topic of אמרי לה כדי that Rashi is supposed to say כדי is a name of a chacham. This source is not cited in the excellent essay on the topic in R. M. Friemann, Pores Mapah, pp. 61-94. See also Mar Kishisha, p. 121; D. Halivni, Mavos Limekorot Umesorot, pp. 34-35]. Shu”t Zion Lenefesh Chayah, Siman 109 [This is the famous Teshuvah where he attacks R. Reuven Margolios for plagiarism in his work Nefesh Chayah. He claims that he stole a particular piece from R. Meir Arik in his Tal Torah. He then goes on to note that Shadal has a piece on the topic. While I hope to return to this teshuvah to see what the exact claims of plagiarism are, in this case I do not see why R. Leiter assumes he stole this from R. Arik]. Note that R. Leiter thanks Alexander Marx and Boaz Cohen of the JTS in the English Foreward, and prays,” Remember this unto them, O G-d, for good.” See also the introduction to S. Freehof The Responsa Literature, where he thanks R. Leiter.

[11] In the Sefer Hazichron for the Seridei Eish, p. 109, 113. R. Hillman was known for not being a big liberal.

[12] This list is found in back of his Mevaser Ezra on Ibn Ezra p. 175. To be sure R. Roth was not a liberal, as is well known with the incident when he was supposed to receive the Kook prize with Saul Lieberman and he refused it. See: Iggeros of R. M. Roth recently printed; Marc B. Shapiro, Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, pp.27-36.

[13] For a listing of all printings of the Ha-Kesav Ve-ha-Kabbalah see N. Ben Menachem, ‘Shtei Iggrot R. Yaakov Tzvi Meklenburg’, Sinai 65 (1969), pp. 327-332. For more on Rabbi Yaakov Mecklenburg and his Ha-Kesav Ve-ha-Kabbalah See: D. Druck, “Ha-Gaon Rabbi Jacob Zvi Mecklenburg,” Chorev4:1-2 (March – September 1937): 171-179 (Hebrew); C. Rabinowitz,’ R. Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg’, Sinai 57, pp. 68-75; Jay M. Harris, How Do We Know This? Midrash and the Modern Fragmentation of Judaism (Albany: SUNY Press, 1995), 212-220; Michal Dell – Orthodox Biblical Exegesis in an Age of Change – Polemics in the Torah Commentaries of R. J.Z. Mecklenburg and Malbim, PhD, Bar-Ilan University, 2008; Hebrew.

[14] Edward Breuer writes that he was unable to locate the source of this letter from Shadal (p. 271 fn. 39). I would like to suggest that as later in that article (p. 272) Breuer notes that the only published works of Shadal that Rabbi Yaakov Mecklenburg could have seen at this point was OhevGer and various articles in journals and that he corresponded with Shadal about his Ha-Kesav Ve-ha-Kabbalah (Igros Shadal, 5, pp. 647-648), so perhaps this too was a letter from Shadal written to Rabbi Yaakov Z. Mecklenburg. But S. of On the Main Line informed me that the letter is printed in Bikure Ha-ittim 7 (Vienna 1826) pg. 183 (link), under the title “המלות גזרת ענין (Etymologia),” and therefore was not specifically sent to Mecklenburg.

[15] Between Haskalah and Orthodoxy: The writings of R. Jacob Zvi Meklenberg, HUCA, 66, 1995, pp. 259-287.

[15b] See Hamaayan 45:1 (2005) p. 74 where Y. Katon writes against him. After quoting Shadal deploring Zunz’s departure from traditional faith, Katon says that Shadal was himself guilty of this and doesn’t belong in a yeshiva curriculum.

[15b] See Hamaayan 45:1 (2005) p. 74 where Y. Katon writes against him. After quoting Shadal deploring Zunz’s departure from traditional faith, Katon says that Shadal was himself guilty of this and doesn’t belong in a yeshiva curriculum.

[16] See Breuer, p. 282. As an aside, Breuer points out (p. 281) that in the second edition Rabbi Yaakov Mecklenburg added a bunch of pieces from the Zohar, and also omitted a small number of comments from Shadal, Wessely and R. Shlomo Pappenheim. Note that many references to Shadal and Wessely remain in the commentary and are in all the editions to this day. Also note that the Latin title page in the 1839 edition, where it is named “Scriptura Ac Traditio,” was changed to German in the later editions, where it is titled “Schrift und Tradition.”

For more on Shadal’s work see, J. Penkower, ‘S. D. Luzzatto, Vowels and Accents and the Date ofthe Zohar’, Italia: Conference Supplement Series 2, Samuel David Luzzatto: The Bi-Centennial of His Birth, Magnes 2004, 79 – 13 [= Al Zeman Chiburim Shel Sefer HaZohar Vesefer HaBahir, 2011, pp. 75-116]; B. Huss, Kezohar Harekiyah, pp. 346-347

[17] See here for an English translation of this part ofthe Vikuach, and here for the entire translation by R. Josh Waxman of Parshablog. On the general question, see R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach Halichos Shlomo, Moadim , 1 pp. 428-434.

[18] Hatorah VeHachochma, pp. 135- 153. The part I am quoting is on p. 143. See Shadal’s Response in Hatorah VeHachochma, pp. 148-149.

[19] Ohev Ger, p. 86.

[20] See: Z. Shazar, MePardes HaTanach,pp. 179-183; M. Margolies, Samuel David Luzzatto: His life and works, pp. 120-123; S. Vargon, Shadal Kecholetz Chokrei Hamikrah Hayehudim, Iyuni Mikra, 6, pp. 71-148; S. Vargon Yechasu shel Shadal le-farshanut ha-halakkah shel Chazal JSIS @ (2003) ; E. Chamiel, author of “Life in Two Worlds, ‘The Middle Way’: Religious Responses to Modernity in the Philosophy of Z.H. Chajes, S.R. Hirsch and S.D.Luzzatto,” (Hebrew; unpublished dissertation, Hebrew University ofJerusalem, 2006).

On the general topic of Shadal here, regarding targumim and our Mesorah, see R. Chaim Heller, Al Targum Hashivim; Seridei Eish, Mechkarim Betalmud, pp. 145-146; M. Shapiro, Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy, pp. 169-170. Also see M. Shapiro, ‘On Targum and Tradition: J.J. Weinberg, Paul Kahle and Exodus 4:22’, Henoch Vol. XIX, 1997, pp. 215-232.

[21] Much has been written on this controversy. See, e.g., M. Samet, Chodosh Assur Min Hatorah, pp. 67-92. But a full treatment in a doctorate is still needed. See also

S. Feiner מהפכת הנאורות pp. 16-187.

S. Feiner מהפכת הנאורות pp. 16-187.

[22] The list of gedolim who appreciated Wessely’s commentary to Vayikra is not small. See here for the reported attitude of the Steipler and his son R. Chaim Shlit”a. The Vilna Gaon too is reported by Kalman Schulmann to have really admired this commentary. Schulmann gives as his source R. Meir Raseiner, a talmid of the Gra, who personally told him this. The gist of all the admiration is thatWessely did an excellent job tying together peshuto shel mikra and the halakhic interpretation of Chazal. In this he was a pioneer and precursor to Mecklenburg and Malbim.

These are the pages in Kovets Beis Aharon ve-Yisrael which list many who used the works of Wessely:

These are the pages in Kovets Beis Aharon ve-Yisrael which list many who used the works of Wessely:

[24] Zera Kodesh, p. 16b, 17b, Igres Rishpei Kodesh, p. 41.

[25] See Gil Perl, Emekha-Neziv A Window into the Intellectual Universe of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin, PhD dissertation, Harvard University (2006), p. 143.

[26] Haggadah shel Pesach, Beis Mordechai, p. 67.

[27] Haggadah Shel Pesach, p. 24, 52; Maamor Talachos Haagaddos, p. 9

[28] Netzach Yisroel, p. 166 but see ibid. p. 52, 22.

[29] Shut, O.C. p. 467.

[30] He had all his works in his collection, see Ohel Avraham, and above, note 6.

[31] Shearis Yakov, p. 14a.

[32] Zichron Chaim, p. 8a.

[33] See Y. Mark, Be-mechitzasom Shel Gedolei Hador, p. 54.

[34] Matzav Hayashar, 2, p. 94.

[35] See Pirkei Zichronos (p. 255) where Ben-Tzion Dinur writes that he used to quote it often and praise it. See also S. Stampfer, The Lithuanian Yeshiva, heb., p. 354.

[36] Introduction to Chumash Vayikra, p. 14: כמו כן ידוע הביאור המצוייןלתורת כהנים מאת נפתלי הירץ ויזל