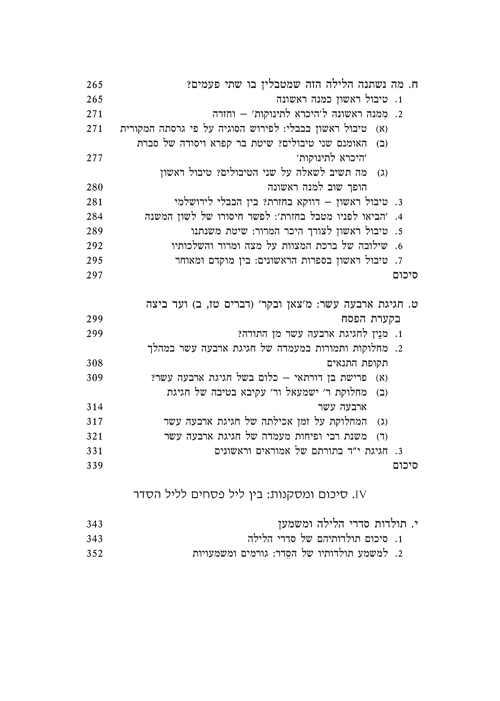

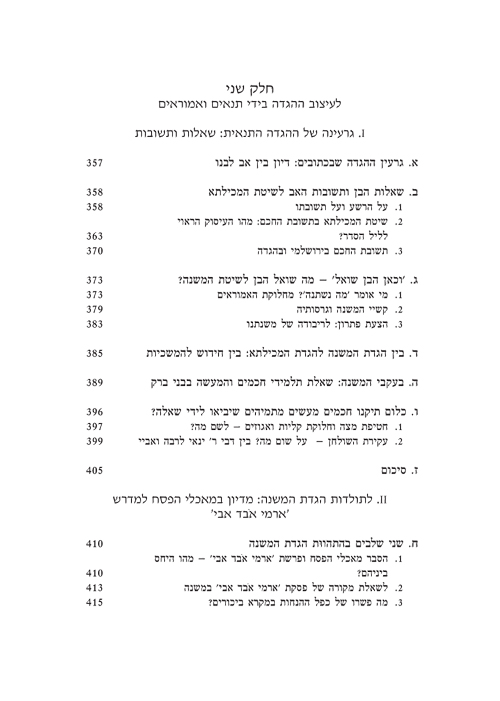

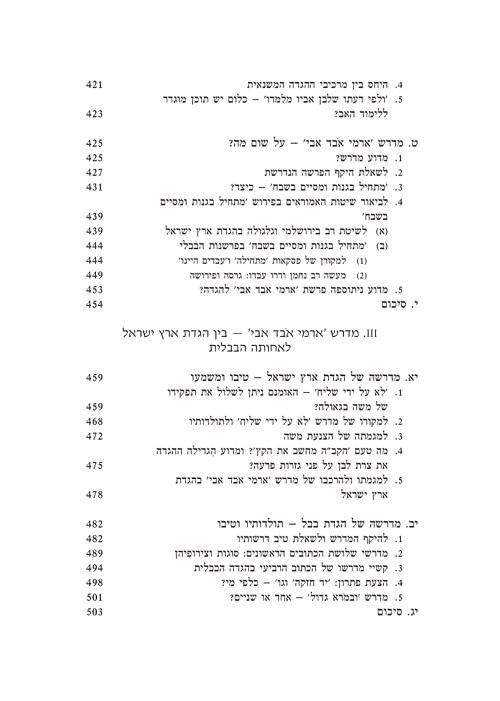

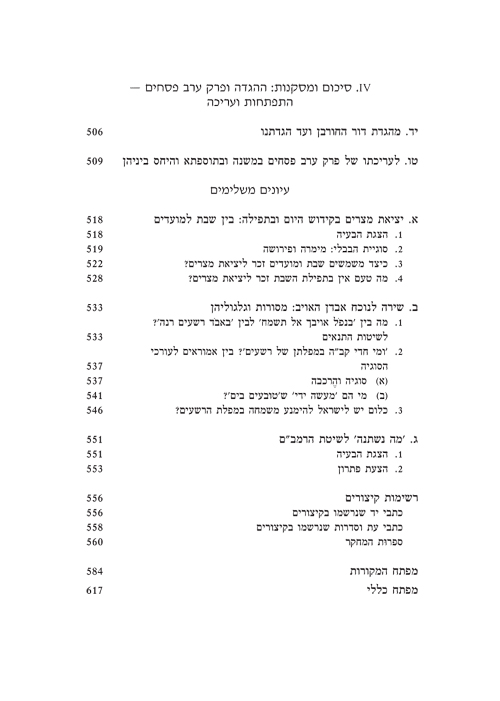

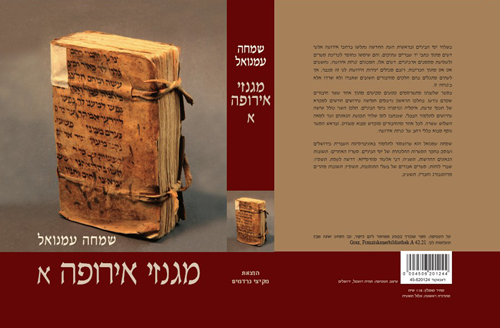

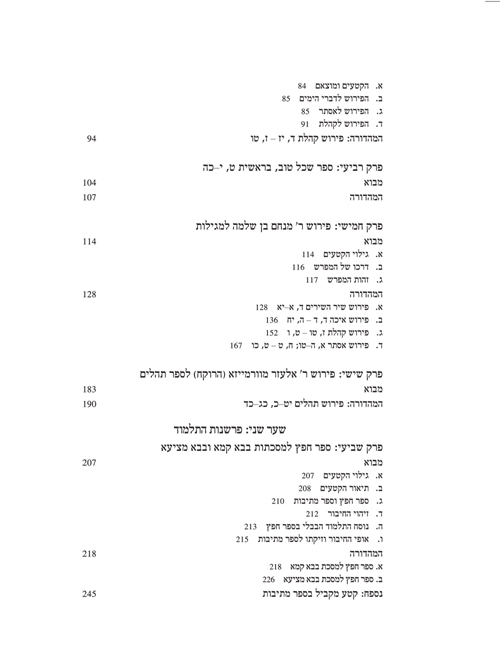

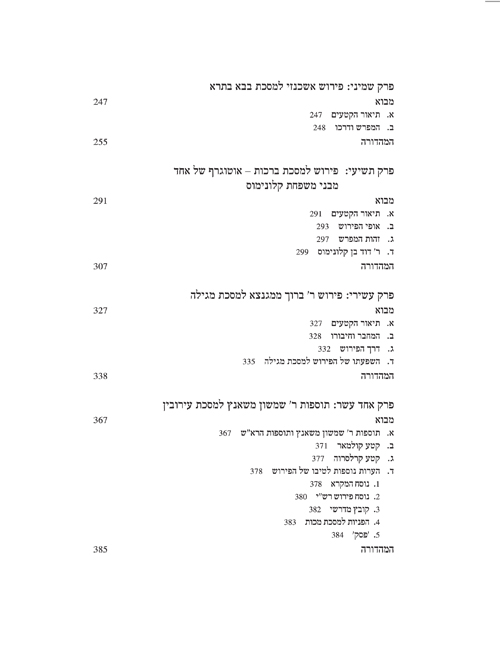

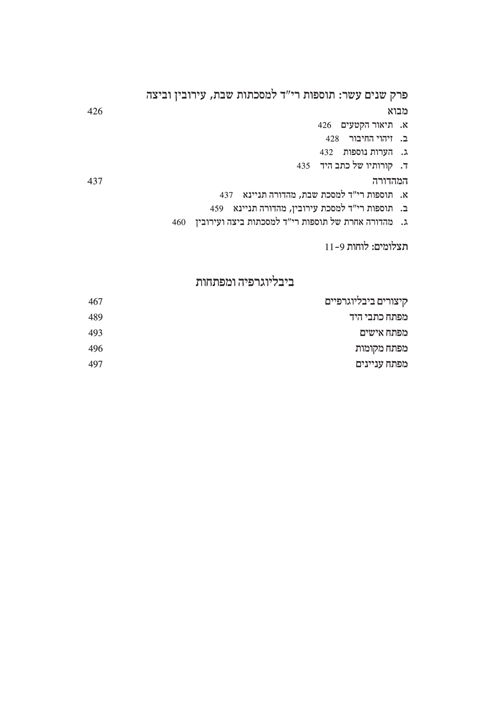

New book announcement: Professor David Henshke’s work on the Seder Night

מגנס, 626 עמודים

Perhaps the topic which has engendered the most commentary in Jewish literature is the Haggadah shel Pesach. There are all kinds, in all languages, and with all types of commentary, pictures, etc. Whatever style one can think of, not one, but many Haggadahs have been written. So, whether it’s derush, kabbalah, halakha, mussar or chassidus there are plenty of Haggadahs out there. Then, there are people who specialize in collecting haggadahs although they do not regularly collect seforim. In almost every Jewish house today one can find many kinds of Haggadahs. In 1901 Shmuel Wiener, in A Bibliography of the Passover Haggadah, started to list all the different printings of the Haggadah. Later, in 1960, Abraham Yaari, in his work A Bibliography of the Passover Haggadah, restarted the listing and reached the number 2700. After that, many bibliographers added ones which Yaari omitted. In 1997, Yitzchak Yudlov printed his bibliography on the Haggadah, The Haggadah Thesaurus. This thesaurus contains a beautiful bibliography of the Pesach Haggadahs from the beginning of printing until 1960. The final number in his bibliography listing is 4715. Of course ever since 1960 there has been many more printed. Every year people print new ones; even people who had never written on the Haggadah have had a Haggadah published under their name, based on culling their other writings and collecting material on the Haggadah. When one goes to the seforim store before Pesach it has become the custom to buy at least one new Haggadah; of course one finds themselves overwhelmed not knowing which to pick!

Here are Professor Henshke’s own words (from the introduction to this work) explaining what it is he is trying to bring to the table (I have abridged the text and footnotes):

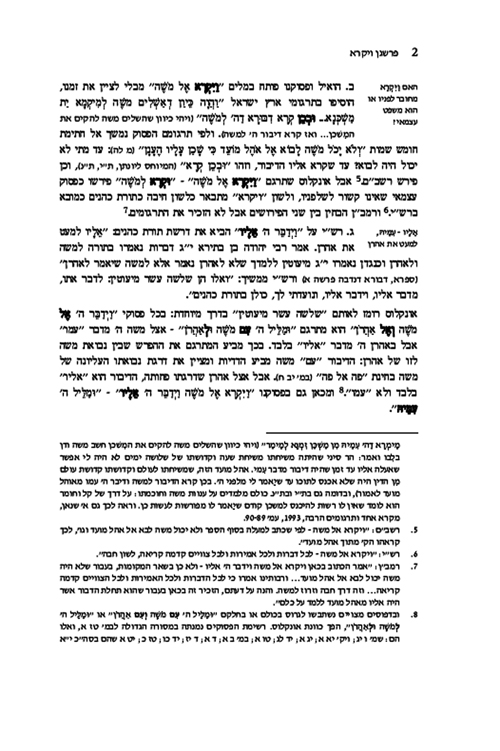

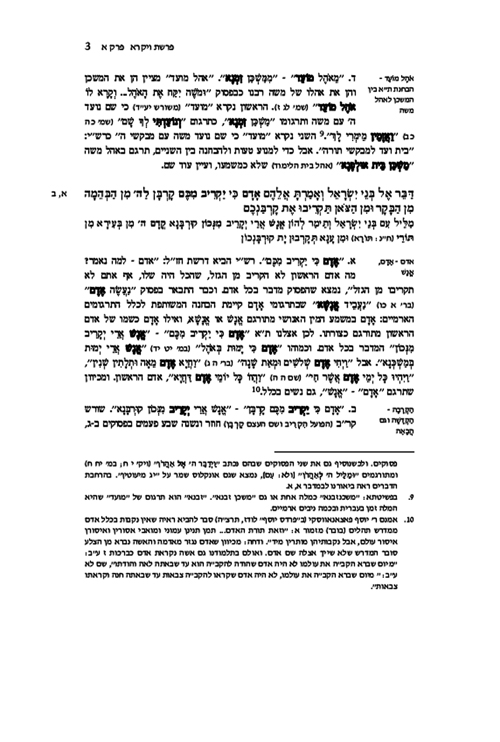

כלום לא נכתב די על ליל הסדר?[1] השאלה… אכן מתבקשת – אף על פי שחיבור זה אינו פירוש להגדה (שאין מספר לביאוריה),[2] ואף אינו דיון תורני בסוגיות ליל הפסח (שדה שאף הוא כבר נחרש עמוקות).[3] תכליתו של ספר זה כפולה – בירור מצווֹת ליל הסדר היסודיות מבחינת תולדות ההלכה בתקופת התנאים והאמוראים (והוא חלקו הראשון שלחיבור), והבהרת התהווּתה של ההגדה התנאית – מימות התנאים עצמם ועד עיצובו של הרובד התנאי בהגדה של ימי האמוראים והגאונים (חלק שני). אף על פי כן, השאלה שבכותרת במקומה עומדת, לפי שסִפרות המחקר על ליל הסדר, שעניינה בתכליות הללו, אף היא כבר רחבה ומסועפת

ברם, לא מעט מסִפרות המחקר נכתב מתוך מבט חיצוני לגופו של החומר הנחקר. חוקרי ליל הסדר לרוב לא ראו את תפקידם בניתוח מהלכי הסוגיות התלמודיות (המשמשות מקור ראשון לענייננו) מפנימן, אלא בהצבת נקודת מוצא שמחוץ להלכי המחשבה התלמודית – כמנוף לבירור מחודש של התופעות. כך, לדוגמאות אחדות, נחקרה ההגדה על רקע פוליטי,[4] על-פי תרבות הסימפוזיון ההלניסטי,[5] או כתגובה לפסחא הנוצרית ול’הגדתה’[6] – אך נקודות מוצא אלה, שאין כלל ספק בחיוניותן, ראוי להן להישקל דווקא לאחר בירור תלמודי מדוקדק בכל כלי הניתוח

שמדע התלמוד של ימינו מְספק. ומעין דבריו של רא”ש רוזנטל: “לא יהיה בסופו של דבר שום מבוא אל התלמוד אלא בתלמודיות ממש“.[7] אין לדלג אפוא אל מעבר לגופי המקורות – קודם שהללו נתבררו מתוכם ככל שיד העיון משגת.

כיצד יש להם למקורות להתברר? על שלושה דברים עומד מחקר התלמוד:[8] (א) בירור שיטתי של נוסח המקורות התלמודיים, על יסוד מכלול עדי הנוסח שבידינו ויחסיהם ההדדיים; (ב) הבהרת לשונם של המקורות, על-פי פשוטם בהקשרם ועל יסוד בדיקתם בשאר היקרויות; (ג) על בסיס שני אלה מתאפשרת העֲמידה החיונית על הרכבם הספרותי של המקורות, הבחנת רובדיהם אלה מאלה ועמידה על יחסיהם ההדדיים. קשיים ותמיהות שמערימות הסוגיות השונות מתיישבים תחילה מתוך בירורים פנימיים אלה, אשר מביאים לעמידה על מהלכי החשיבה התלמודיים ותולדותיהם; ומעֵין וריאציה על התער של אוקהם[9] דומה שמלמדת כי דווקא כאשר אין בכל אלה כדי להושיע, יש מקום לפנות אל מחוץ לסוגיות עצמן

אימוצה של מתודה זו בסוגיא דילן[10] דומה שמשיב כל הצורך על השאלה שהוצגה…, כפי שמתברר בבדיקת הסִפרות הקיימת

סקירה מפורטת של ספרות המחקר בפרשת ליל הסדר, כפי שנדפסה עד שנת תשנ”ו, מצויה במבואו של יוסף תבורי לחיבורו ‘פסח דורות’ (תל-אביב 1996). במרכזה של ספרות זו עומדות כמדומה הגדותיהם של ד’ גולדשמידט (תש”ך) ורמ”מ כשר (מהדורה שלישית תשכ”ז), כל אחת בדרכה; אך תיאורן של דרכים אלה, יחד עם הצגת שאר הספרות בענייננו, ימצא הקורא במבואו האמור של תבורי. ואילו גוף ספרו הוא ודאי נקודת מפנה בחקר הלכות ליל הסדר; כי בחיבור זה מונחת תשתית שאין לה תחליף בתחום הנדון, וכל מחקר הבא אחריו נזון הימנו.[11] ברם, נוסף לנתונים הרבים שנתגלו ונצטברו מיום הופעת ספרו של תבורי (שבנוי בעיקרו על דיסרטציה משנת תשל”ח) – ויָתר עליהם: דרכי חשיבה וניתוח שנתחדדו מאז – הרי כבר הודיע המחבר עצמו כי “עיקר החידוש שלי הוא בתיאור תולדות הלכות ליל הסדר בתקופה הבתר אמוראית” (עמ’ 27; ההדגשה שלי). ואילו חיבורִי מוקדש בעיקרו לסִפרות התנאים והאמוראים.[12]

מתוך כלל הסִפרות שיצאה לאור לאחר ספרו של תבורי, אזכיר כאן שני חיבורים שנזקקתי להם רבות. בשנת תשנ”ח יצאה לאור ‘הגדת חז”ל’ מאת שמואל וזאב ספראי. זהו חיבור רב ערך שריכז נתונים הרבה, והוא כתוב בידי אב ובנו, שני היסטוריונים מומחים; אלא שהיסטוריה היא אכן מגמתם, ולא בירורי הסוגיות התלמודיות לשמן… ולא עוד אלא שספר זה מוקדש להגדה דווקא, ומצוות ליל הסדר נידונות בו רק אגבה. מכל מקום, הכרת תודה יש בי אף לחיבור זה, שאי אפשר לחוקר ליל הסדר שלא להיזקק לו

משנה ותוספתא פסחים הן נושא חיבורו של שמא יהודה פרידמן, ‘תוספתא עתיקתא’ (רמת-גן תשס”ג), שבכללו סעיפים העוסקים בענייננו. כדרכו, אין דבר גדול או קטן במהלך הדברים שפרידמן אינו יורד לסוף עניינו ומבררו כשׂמלה. ברם, נקודת המוצא של חיבור זה היא השיטה הכללית המוצעת בו, בדבר קדמותן של הלכות התוספתא להלכות המשנה המקבילות… מכל מקום, כל אימת שחיבורו של פרידמן נגע בענייננו, מיצוי מידותיו היה מאלף

He has written over 100 articles and two books (here and here) developing and elaborating on his methods.

[2] ראה: יודלוב, אוצר, שם נרשמו “קרוב לחמש מאות פירושים… ממזרח וממערב, מכל קצות הקשת המחשבתית רבת הגונים והענפים שבעולם האמונה והמחשבה היהודית לדורותיה”, כדברי י”מ תא-שמע בהקדמתו שם, עמ’ ח, והואיל והרישום מגיע שם לשנת תש”ך, הרי כיום יש להוסיף כמובן לא מעט; אך מעֵבר לכך, רשימה זו אינה כוללת אלא את דפוסי ההגדות המלוּות בפירושים, ואילו לביאורי ההגדה שמצאו מקומם בשאר כל הספרות התורנית דומה שאין מספר

[3] ראה, לדוגמה בעלמא, מפתח הספרים שבסוף אוצר מפרשי התלמוד – פסחים, ד: ערבי פסחים, ירושלם תשנ”ד, עמ’ תתסט-תתצח.

[4] ראה למשל פינקלשטיין, א-ב..

[5] ראה למשל מאמרו רב ההשפעה של שטיין, סימפוזיון; על הבעייתיות שבכיווּן זה ראה להלן..

[6] ראה למשל דאובה שצוין להלן…, ובעקבותיו יובל, שני גוים, עמ’ 92; על כך שההנחה שביסוד דברי דאובה אינה מתקיימת, ראה להלן שם בהמשך. רעיונותיו המעניינים של יובל, המתאר את ההגדה כתגובה לנצרות, בעייתיים מבחינת בירור המקורות; ראה על כך עוד, לדוגמה, להלן… בתחום היחס לנצרות מצוי גם חיבורו של ליאונרד, אך הלה מבקש לברר את העניינים גם מתוכם. אלא שאף כאן ניכרת היטב בעייתיות ברקע התלמודי; וראה, לדוגמה, להלן…

[7] רוזנטל, המורה, עמ’ טו

[8] השווה: רוזנטל שם; ספרִי שמחת הרגל, עמ’ 2-1

[9] כבר העירו על ניסוחו של הרמב”ם, בקהיר של המאה הי”ב, לעקרונו של ויליאם איש אוקהם, באנגליה של המאה הי”ד: “אם, למשל, יש ביכולתנו להניח מתכונת אשר על-פיה תהיינה אפשריות התנועות… על-פי שלושה גלגלים, ומתכונת אחרת אשר על-פיה יתאפשר אותו דבר עצמו על-פי ארבעה גלגלים, ראוי לנו לסמוך על המתכונת אשר מספר התנועות בה קטן יותר” (מורה הנבוכים ב, יא, מהד’ שורץ עמ’ 290). ואכמ”ל במקורותיו.

[10] החיבור הנוכחי איננו הראשון שבו מבקש אני לבחון ולהדגים מתודה זו; שני קודמיו (משנה ראשונה; שמחת הרגל) נתמקדו בתורת התנאים..

[11] לחיבורו זה הוסיף תבורי מחקרים נוספים בענייני ליל הסדר, ואלה שנזכרו בחיבורנו רשומים ברשימת ספרות המחקר שבסופו; וראה עוד סיכומו “The Passover Haggadah”, בתוך: S. Safrai et al. (eds.), The Literature of the Sages, II, Assen 2006, pp. 327-338

[12] דיונים בספרות הגאונים והראשונים נערכו כאן כשיש בהם כדי להבהיר את הכיווּנים שהועלו באשר להלכה החז”לית.