The Medical Training and

Yet Another (Previously Unknown) Legacy

of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, zt”l

by Edward Reichman and Menachem Butler

Rabbi Dr. Edward Reichman is a Professor of Emergency Medicine and Professor in the Division of Education and Bioethics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He writes and lectures widely in the field of Jewish medical ethics.

Mr. Menachem Butler is Program Fellow for Jewish Legal Studies at The Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School. He is an Editor at Tablet Magazine and a Co-Editor at the Seforim Blog.

On erev Shabbat Shira last week, in the course of a typically wide-ranging conversation between the authors of this article, Menachem mentioned that unfortunately Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski was critically ill. As hashgachah would have it, Menachem had happened upon a little-known precious work from 1997, entitled Sefer Ye’omar le-Yaakov u-le-Yisrael, compiled by Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski and comprised of letters written to him by Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, zt”l (1899-1985), known as the Steipler Gaon and author of the multi-volume work Kehillot Yaakov.[1]

Scion of prominent Hasidic dynasties and related to the current Rebbes of Bobov, Karlin, Klausenberg, Talner, and Skver, Abraham J. Twerski was born in Milwaukee in 1930 to Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Twerski and his wife Devorah Leah (née Halberstam), where he attended public school as a child.[2] After he received his rabbinic ordination from the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago, he began to serve as an assistant rabbi in his father’s congregation in Milwaukee in the 1950s, as Aaron Katz described in his 2015 profile of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski (“The Wisdom of Peanuts”) at Tablet Magazine. He married Goldie (née Flusberg) in March 1952; and starting that summer, directed the Hebrew School at his father’s congregation Beth Jehudah, as well as officiated religious lifecycle events in his father’s community in Milwaukee. However, as he would later reflect in an interview “after I had practiced as a rabbi for a number of years, I felt I was not fulfilled in my work and — after consultation with the Steipler Gaon — I went to medical school to become a psychiatrist.”

Abraham J. Twerski wrote to the Steipler Gaon and expressed concerns about the propriety of attending medical school as an Orthodox Jew. He would regularly visit Rav Kanievsky at his home in Bnei Brak and corresponded with him by mail, maintaining an ongoing relationship with him until the Steipler’s passing in 1985. That year, a volume of collection of letters entitled Karyana de-Igarta was published, and included, for the first time, two letters that the Steipler Gaon had sent some thirty years earlier to a young Abraham J. Twerski in Milwaukee, who was then seeking his advice regarding his career choice.

The first letter was written at the end of the Summer of 1955 by a twenty-four-year-old Abraham J. Twerski and in this letter the Steipler Gaon addresses the value of making one’s livelihood through a non-rabbinic profession. As to the specific profession, he adds that medicine may be a preferred choice, as it is a mitzvah to learn, and additionally, excluded from the ban on secular knowledge of the Rashba.[3] However, this is on the proviso that the education is provided by proper teachers and in an environment conducive to Torah observance. As this is clearly not the case in a modern university, he offers some general guidelines, culled from the seforim hakedoshim, if not to guarantee, at least to enhance the chances of success: 1) kove’a itim – learn in-depth at least two hours daily; 2) recite all tefillos with a minyan; 3) regular mikva immersion; 4) meticulous Shabbat observance; and 5) a daily musar seder.[4]

The second question Abraham J. Twerski posed, the following year, was more specific to his situation. He inquired whether it was preferrable for him to be a rabbi in a largely non-observant community (he was serving as an assistant rabbi to his father in Milwaukee at that time), which would involve immersion in an irreligious environment with potential negative impact on the Jewish education of his children; or should he choose a medical career, which would allow him to remain in an environment of Torah observance.

Suffice it say, the Steipler Gaon’s tone in this letter is less than supportive of a career in medicine than its predecessor. His written response is unequivocal, “the rabbinate is much preferred” (adifa yoter viyoter). He lists no less than five reasons not to become a physician, relating to the challenges in maintaining Torah observance and modesty, as well as the time commitment, which would preclude Torah study. He adds on a personal note that given his estimation of the exceptional talents of the young Rabbi Twerski, the latter would likely become a highly successful and sought-after physician. As such, he would find no rest from those constantly “knocking on his door” and seeking his consultation. He was particularly concerned about what would happen to his Torah learning and observance in such a case.[5]

Notwithstanding the serious concerns expressed by the Steipler Gaon, and perhaps now better informed of the potential pitfalls, Abraham J. Twerski proceeded to pursue his medical education, as he wrote, “I went to medical school with the Steipler’s blessing and continued an ongoing relationship with him for years.”[6] Their fathers both grew up as friends in Hornsteipel, “and spent their boyhood years together and were on first name terms,” reminisced Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski many years later in a biographical memoir of his Hasidic ancestors.[7]

However, several years into his studies at Marquette University’s medical school, Abraham J. Twerski could no longer afford the tuition.[8] His assistance would come from a most unlikely source, as he would later describe in an interview with the Pittsburgh Quarterly:[9]

By that time, I had several children, so my dad and some members of the congregation helped me to pay for school. I applied for a scholarship through a foundation, but it didn’t come through, so in my third year, I fell two trimesters behind on tuition. One day, I called my wife at lunch as always, and she asked, “What would you do if you had $4,000?” I said, “I’m too busy to talk about fantasies.” She said, “But you really do have $4,000!” I said, “From where?” She said, “From Danny Thomas.” “Who’s Danny Thomas?” She said, “The TV star.” Then she read me an article from The Chicago Sun. Local officials had told Mr. Thomas about a young rabbi who was struggling to get through medical school. Thomas asked, “How much does your rabbi need?” They said, “Four thousand dollars.” He said, “Tell your rabbi he’s got it.”[10] So, I did my internship in general medicine, went to the University of Pittsburgh Psychiatric Institute for three years, and then worked two more years for a state hospital.

While the Steipler Gaon’s assessment of the success of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski’s medical career was prophetic, his concerns about Torah observance and learning, at least for Dr. Twerski, would turn out to be unfounded. Upon his graduation from medical school several years later, Time Magazine (June 15, 1959) published a brief article about him entitled “Rabbi in White.” It is worth reprinting in its entirety:

Abraham Joshua Twerski, 28, graduated from medical school this week. It was no mean feat, for Twerski is a Jewish rabbi like his father, two uncles, father-in-law, two older brothers and (when they finish their studies) two younger twin brothers. And to keep the Torah as an Orthodox Jew for six years of studies in Milwaukee’s Roman Catholic Marquette University was something like running a sack race, an egg race and an army obstacle course at the same time.

First there was the problem of keeping his religion from growing rusty: he rose each day at 5:30am, put in an hour’s study of the Talmud before early service at Milwaukee’s Beth Jehuda Synagogue, where he is assistant rabbi. Medical school classes began at 8am, and here real complications set in. His full black beard was a sanitary problem in surgery, requiring special snood-like surgical masks. His tallith katan, a small prayer shawl worn by many Orthodox Jews under their shirts, had to be made of cotton instead of wool – which might set off a static spark and ignite the anesthetic in an operating room.

Lectures on Saturday.[11] Religious holidays sometimes required months of advance planning. The nine-day Feast of Tabernacles, for instance, with four days when work is forbidden, fell during a series of lectures before a make-or-break exam in pathology. Abe, as students and professors call him, met the situation by studying by himself all the preceding summer, put himself so far ahead of his class that he could afford to miss the lectures. “I hated like heck to miss them,” he explains, “but I creamed that exam.”

When lectures came on Saturdays – during which Orthodox Jews are forbidden to work, ride in a vehicle or talk on the phone – Abe would have a friend put a sheet of carbon paper under his lecture notes and hope he remembered to use a ballpoint pen. Sabbath restrictions begin on Friday night, just before sundown, and on occasion Fridays only a lucky break in the traffic has saved him from having to abandon his 1952 De Soto and walk the rest of the way home. On Saturdays Abe was not on duty, but sometimes, to follow up on one of the cases he had been observing, he would leave his car in the garage and walk five miles to the hospital and back.

Work on Tishah Be’ab. Abe brought his own kosher food to school every day and ate it in the student lounge, where he also said his midday prayers in a corner, surrounded by chattering fellow students. Hospital duty during the 24-hour fast without food and water at Tishah Be’ab (commemorating the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D.) Dr. Twerski describes as “murder,” and the last six years have left him hollow-eyed and slightly sallow.[12] But he is eagerly looking forward to the next stage: a year of internship in Milwaukee’s Mount Sinai Hospital, followed by a three-year residency in psychiatry.

“Psychiatric training was the motivation for my going into medicine,” he says. “I felt I could be a better adviser to my people and more help to them with their problems.”

The Time Magazine profile of Abraham J. Twerski included just one photograph (wearing “a snood for surgery” over his yarmulke), but members of the Twerski family have shared in recent years nearly a dozen of the other photographs that were taken by George P. Koshollek Jr., a local photographer with The Milwaukee Journal, and later deposited in the LIFE Photo Archive. The following are two photographs of newly-minted physician Abraham J. Twerski, together with his philanthropic patron who supported his medical school studies, the comedian Danny Thomas:

Upon his 1959 graduation from Marquette University Medical School, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski left his pulpit in Milwaukee and moved with his family to Pittsburgh, where he completed his psychiatric training at the University of Pittsburgh’s Western Psychiatric Institute four years later, and was then named clinical director of the Department of Psychiatry at St. Francis General Hospital in Pittsburgh, supervised by Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, where he advanced his expertise for treating addiction. In 1972, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski founded the Gateway Rehabilitation Center with the Sisters of St. Francis.[13]

Returning to our pre-Shabbat conversation, Menachem suggested that perhaps it might be appropriate for us to study through the 1997 volume of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, Sefer Ye’omar le-Yaakov u-le-Yisrael – one of his only Hebrew-language books of more than his eighty-authored volumes published over the past half-century – as a merit for Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski’s complete recovery. Menachem further asked if I would perhaps identify any medically related material that might be significant or previously unknown. Before Shabbat, I identified one particular letter, the final one in the book, which was of medical relevance, and I printed it out for learning, with Rabbi Twerski in mind. The topic: the obligation to prolong the life of a critically ill patient.

Just two days after our conversation, we read of the tragic passing of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, whose passing took place on Sunday, Chai Shvat 5781 (January 31, 2021). The nature of the letter from the Steipler Gaon to Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, and its heretofore unknown origins, compels us to write this brief note l’zecher nishmato (in honor of his memory) and to add yet an additional item to his legacy.

Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski’s astonishing accomplishments, known to the Jewish community worldwide, are primarily in the fields of mental health, self-esteem, and addiction medicine.[14] We will leave it those with expertise in these areas to recall and recount his manifold contributions, including his voluminous literary output.[15] Here we note a contribution, which though indirect, may be on par with respect to its Jewish communal impact as those more widely known.

The Letter

In the introduction to this 230-page-work, Sefer Ye’omar le-Yaakov u-le-Yisrael, published in 1997 by the Kollel Bais Yitzchok on Bartlett Street in Pittsburgh (and with an effusive approbation from Rav Chaim Kanievsky, son of the Steipler Gaon), Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski recounts his unique connection to Rav Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, the Steipler Gaon. It stemmed back to the city in present-day Ukraine called Hornsteipel, to which they both trace their roots.[16] Rav Kanievsky had lived there in his youth and the appellation “the Steipler” is derived from the name of the town. Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, though born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin is a direct descendant of Rebbe Yaakov Yisrael Twerski of Cherkas, the founder of the Hornsteipel Hasidic dynasty, which originated in that city.[17] His father was named Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Twerski and was known both as the Hornsteipler Rebbe, and as the Milwaukee Rebbe.[18]

The last letter of this volume presents a medical halakhic query Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski posed to the Steipler Gaon in the Summer of 1973 about his ailing father. “May a son administer an injection to his ill father?” Despite the fact that Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski was a physician, and injections were part of his clinical scope of practice, he was acutely aware of the potential halakhic ramification of something as simple as an injection. An injection may cause bodily injury, and it is Biblically prohibited for a son to cause a wound to his father.[19] Rav Kanievsky answered that it would be permitted as long as there are no other options: “On the matter of delivering an injection to one’s father, as it may cause a wound, the law is found in Yoreh De’ah #241:3, that when no one else is available, it is permitted … .”[20]

It appears however that between the sending of the query and the completion of the response, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski’s father passed away, as Rav Kanievsky offers condolences: “Behold, I who am bereft of good deeds [an allusion to the introduction to the High Holiday Musaf prayer recited by the chazzan] join in your great sorrow upon the passing of the honorable, great rabbi of the Hornsteipel dynasty. May God comfort you among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem, and may his memory be a blessing for eternity.”[21]

It is the following paragraph, which includes a general comment about end-of-life issues, to which we draw your attention:

“Regarding the principle that one should do everything possible to prolong the life of the ill patient [even if he is in a terminal state (chayei sha’ah)]. In truth I also heard such a notion in my youth, and I do not know if this derives from a ‘bar samcha’ (authoritative source). In my opinion, this requires serious analysis…”

As I [ER] read these words, they were familiar to me. This letter appears in the Steipler Gaon’s collection of letters entitled Karyana de-Igarta,[22] though the questioner is not identified. It is only from this work of their correspondences that we learn that Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski is the author of the query!

It is not a lengthy halakhic analysis. In fact, the Steipler Gaon goes on to cite only two sources. The citations relate to the passage in Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh De’ah #339 regarding the treatment of a ‘gosses’, one whose death is imminent. Yet this pronouncement of Rav Kanievsky’s on the approach to the patient at the end of life may possibly be his most cited reference on any medical halakhic topic. Moreover, it is one of the more frequently cited sources in contemporary halakhic discussions on the end of life.

In the Modern era, with the likes of respirators and antibiotics, we now have the ability to prolong life to an extent not imaginable in the past. Must we utilize the entire armamentarium of medicine to prolong life in every circumstance, despite any associated suffering? There are some, such as Rav Eliezer Waldenberg, zt”l, who would answer in the affirmative.[23] Others, like Rav Moshe Feinstein, zt”l, allow for circumstances to refrain from aggressive care.[24] This debate has been the substance of halakhic discussions on end-of-life care in our generation.[25]

For someone of the stature of Rav Kanievsky’s to write that the notion to prolong life in all circumstances and at all costs may not derive from a “bar samcha” (authoritative source) is nothing short of revelational. This statement has guided many a rabbinic authority in their general approach to the treatment of the patient at the end-of-life and has certainly been part of the thought process of countless practical halakhic decisions.

It appears that this noteworthy contribution of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, zt”l to medical halakhic discourse, albeit indirect, has gone largely unnoticed. He is not only to be credited for his legendary contributions to broadening the possibilities of mental health in the Jewish community and beyond,[26] but he is also responsible for eliciting this letter of Rav Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, which has informed and guided halakhic-decision-making at the ‘end-of-life’ in the Modern era.

Sadly, we now invoke the same sentiment that the Steipler Gaon expressed above about the loss of another great rabbinic leader and member of the Hornsteipler dynasty:

May his memory be a blessing for eternity.

Notes:

[1] See Marc B. Shapiro, “The Tamim: Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky (‘The Steipler’),” in Benjamin Brown and Nissim Leon, eds., The Gedolim: Leaders Who Shaped the Israeli Haredi Jewry (Jerusalem: Magnes, 2017), 663-674 (Hebrew). A full biographical treatise on The Steipler Gaon along the lines of the magisterial scholarly work of The Hazon Ish, in Benjamin Brown, The Hazon Ish: Halakhist, Believer and Leader of the Haredi Revolution (Jerusalem: Magnes, 2011; Hebrew) remains a scholarly desideratum.

[2] In a December 25, 2020 email to Menachem Butler, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski clarified some important details of an anecdote from when he participated in the Christmas play at his Milwaukee public school in his childhood. He wrote here:

That’s not quite the way it was. The week after the play, my mother called the teacher, to meet her. The teacher said, ‘I knew that Mrs. Twerski would reprimand me for putting Abraham in the Xmas play. But all she wanted to know was whether Abraham was self-conscious because he was shorter than the other children.’ I said, ‘I thought you were going to reprimand me for putting Abraham in the Xmas play.’ Mrs. Twerski said ‘If what we have given him at home is not enough to prevent an effect of a Xmas play, then we have failed completely.’

[3] For an overview of the controversy, see David Berger, “Judaism and General Culture in Medieval and Early Modern Times,” in Cultures in Collision and Conversation: Essays in the Intellectual History of the Jews (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2011), 21-116, esp. 70-78. See also Joseph Shatzmiller, “Between Abba Mari and Rashba: The Negotiations That Preceded the Ban of Barcelona (1303-1305),” Studies in the History of the Jewish People and the Land of Israel, vol. 3 (1973): 121-137 (Hebrew); David Horwitz, “The Role of Philosophy and Kabbalah in the Works of Rashba,” (unpublished MA thesis, Yeshiva University, 1986); David Horwitz, “Rashba’s Attitude Towards Science and Its Limits,” Torah u-Madda Journal, vol. 3 (1991-1992): 52-81; and Marc Saperstein, “The Conflict over the Ban on Philosophical Study, 1305: A Political Perspective,” in Leadership and Conflict: Tensions in Medieval and Early Modern Jewish History and Culture (Oxford: Littman Library, 2014), 94-112.

[4] Avraham Yeshaya Kanievsky, Karyana de-Igarta: Letters of Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, vol. 1 (Bnei Brak: privately published, 1985), 101-103, no. 86 (Hebrew), dated August 31, 1955.

[5] Avraham Yeshaya Kanievsky, Karyana de-Igarta: Letters of Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, vol. 1 (Bnei Brak: privately published, 1985), 72-74, no. 66 (Hebrew), dated April 5, 1956.

[6] Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, “Who is Honored? He Who Honors Others” (Pirkei Avos 4:1) at TorahWeb.org.

[7] See Abraham J. Twerski, The Zeide Reb Motele: The Life of the Tzaddik Reb Mordechai Dov of Hornosteipel (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002), 11.

In 1965, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski visited Bnei Brak and requested that he be permitted to take a photograph of Rav Kanievsky. After sharing a story about how Rav Meir Shapiro of Lublin convinced Rav Joseph Rosen, the Rogatchover Gaon, to allow him to take a photograph so that future generations would know what “a true Jew should look like,” the Steipler consented to a photograph to be taken.

[8] Financial difficulties for Jewish medical students are certainly not a new phenomenon. Indeed precisely four hundred years before Rabbi Twerski’s financial woes, in 1658, Chayim Palacco, another rabbi training as a physician in the University of Padua Medical School petitioned the Jewish community of Padua for assistance in paying his medical school tuition. The request, the only one of its kind in the archival records, was granted. See Daniel Carpi, “II Rabbino Chayim Polacco, Alias Vital Felix Montalto da Lublino, Dottore in Filosofia e Medicina a Padova (1658),” Quaderni per la Storia dell’ Universita di Padova, vol. 34 (2001): 351-352.

[9] Jeff Sewald, “Abraham J. Twerski, Psychiatrist and Rabbi: The Psychiatrist and Rabbi in His Own Words,” Pittsburgh Quarterly (Winter 2008), available here.

[10] For further details, see “Catholic Danny Thomas to Help Rabbi Become Doctor,” The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle (27 June 1958): 1 and 3.

[11] The medical student Judah Gonzago, who trained in Rome in the early 1700s, recounts how one of his final (oral) exams was on Rosh Hashana. He recalls how he left the synagogue after the shacharit (morning) service and returned in time to hear the blowing of the shofar. His other trials and tribulations are reminiscent of those of Rabbi Dr. Twerski, though reflect a different historical reality. Though not a rabbi, Gonzago taught Torah in the local Jewish school. See Abraham Berliner, “Memoirs of a Roman Ghetto Youth,” Jahrbuch für Jüdische Geschichte und Literatur, vol. 7 (1904): 110-132 (German), of which excerpts are summarized and translated in Harry Friedenwald, “The Jews and the Old Universities,” in Harry Friedenwald, ed., The Jews and Medicine: Essays, vol. 1 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 1944), 221-240.

[12] How Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski navigated medical school while simultaneously maintaining meticulous religious observance, not to mention finding time for Torah learning, is truly exceptional. It reflects the challenges that every religious Jew faces in pursuing a medical education. These challenges have existed throughout history, though they have evolved over time. See Edward Reichman, “From Maimonides the Physician to the Physician at Maimonides Medical Center: The Training of the Jewish Medical Student throughout the Ages,” Verapo Yerape: The Journal of Torah and Medicine of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, vol. 3 (2011): 1-25; Edward Reichman, “The Yeshiva Medical School: The Evolution of Educational Programs Combining Jewish Studies and Medical Training,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, vol. 51, no. 3 (Summer 2019): 41-56. See also Edward Reichman, “The History of the Jewish Medical Student Dissertation: An Evolving Jewish Tradition,” in Jerry Karp and Matthew Schaikewitz, eds., Sacred Training: A Halakhic Guidebook for Medical Students and Residents (New York: Amud Press, 2018), xvii-xxxvii.

[13] See Abraham J. Twerski, The Rabbi & the Nuns: The Inside Story of a Rabbi’s Therapeutic Work With the Sisters of St. Francis (Brooklyn: Mekor Press, 2013).

On his appointment to this position in August 1965, Sister Mary Adele announced: “The addition of Dr. Twerski to our staff is another important move toward our goal of making complete, comprehensive mental health care and treatment available to all the people of the community.” The following month, both Sister Mary Adele and Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski rejected the suggestion that his appointment embodies any aspect of the ecumenical movement, and she told The Pittsburgh Press: “The appointment came at an opportune time to fit into the spirit… but it was accidental.” See “St. Francis Ecumenical Movement? Rabbi, Catholic Hospital Team Up In Psychiatry: Mental Ward on the Move,” The Pittsburgh Press (26 September 1965): 11

[14] Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski’s contributions also extend to the sphere of music. A noted composer of Hasidic melodies (and also of musical grammen that he composed to be delivered at celebratory occasions, such as weddings and sheva brachot), one of his best-known (although often unattributed) compositions is “Hoshia Es Amecha,” which he composed more than six decades ago on the occasion of his brother’s wedding, and set to the words from Tehillim 28:9. The song is often chanted on Simchat Torah following each of the hakkafot in the synagogue, and has become a helpful tune to count the minyan-members ahead of starting prayer services. His story of the song’s composition is recorded here. At his request, there were no eulogies delivered at his funeral. Instead, he requested that his family sing “Hoshia Es Amecha,” which he had once described as his “ticket to Gan Eden…because people dance with it.” See the video of the funeral march here.

[15] For example, see Andrew R. Heinze, “The Americanization of Mussar: Abraham Twerski’s Twelve Steps,” Judaism: A Journal of Jewish Life & Thought, vol. 48, no. 4 (Fall 1999): 450-469.

[16] For the geographic map of the Hasidic dynasties that emerged from Hornsteipel, see Marcin Wodziński, Historical Atlas of Hasidism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 159,162.

[17] See his book-length tribute to Reb Motele, the father of Rebbe Yaakov Yisrael Twerski of Cherkas ancestor, see Abraham J. Twerski, The Zeide Reb Motele: The Life of the Tzaddik Reb Mordechai Dov of Hornosteipel (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002).

[18] See Israel Shenker, “The Twerski Tradition: 10 Generations of Rabbis in the Family,” The New York Times (23 July 1978): 38, which includes a photo of Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael and Devorah Leah Twerski, with their children and their spouses at a family wedding in 1958.

Peter Leo, “He Defies Melting Pot Tradition,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (4 September 1978): 15:

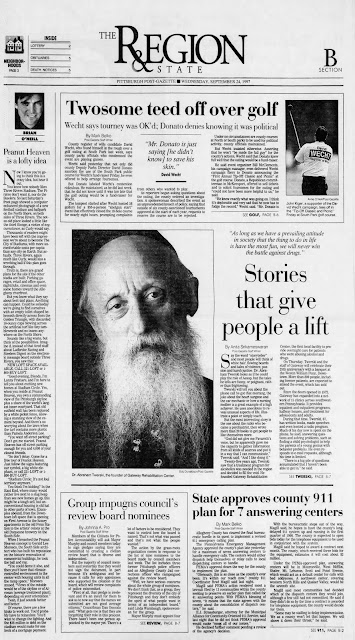

Anita Srikameswaran, “Stories That Give People A Lift,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (24 September 1997): B2,B7

[19] For treatise on the topic of providing medical care to one’s parent, see Avraham Yaakov Goldmintz, Chen Moshe (Jerusalem: privately published, 2002; Hebrew), available here.

[20] Abraham J. Twerski, Sefer Ye’omar le-Yaakov u-le-Yisrael (Pittsburgh: Kollel Bais Yitzchok, 1997), 177 (no. 86) (Hebrew), dated August 27, 1973.

[21] Grand Rebbe Yaakov Yisrael Twerski passed away on August 7, 1973.

[22] Avraham Yeshaya Kanievsky, Karyana de-Igarta: Letters of Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, vol. 1 (Bnei Brak: privately published, 1985), 201, no. 190 (Hebrew)

[23] Alan Jotkowitz, “The Intersection of Halakhah and Science in Medical Ethics: The Approach of Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg,” Hakirah, vol. 19 (2015): 91-115.

[24] See Moshe Dovid Tendler, Responsa of Rav Moshe Feinstein, vol. 1: Care of the Critically Ill (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1996). See also Daniel Sinclair, “Autonomy in Matters of Life and Death and the Withdrawel of Life-Support in the Responsa of Rabbi Moses Feinstein,” Jewish Law Association, vol. 23 (2012): 231-245; and Alan Jotkowitz, “Death as Implacable Enemy – Or Welcome Friend in the Theology and Halakhic Decision Making of Rabbis Moshe Feinstein, Eliezer Waldenberg, and Haim David Halevy,” in Kenneth Collins, Edward Reichman, and Avraham Steinberg, eds., In the Pathway of Maimonides: Festschrift on the Eightieth Birthday of Dr. Fred Rosner (Haifa: Maimonides Research Institute, 2016), 73-99.

[25] For a comprehensive review of the halakhic issues at the end of life – well beyond the scope of this brief essay – see, most recently, Avraham Steinberg, Ha-Refuah ka-Halakhah, vol. 6: The Laws of the Sick, the Physician, and Medicine (Jerusalem: privately published, 2017), 338-388 (section 10) (Hebrew).

[26] See, for example, his books in Abraham J. Twerski, Let Us Make Man: Self Esteem Through Jewishness (Brooklyn: Traditional Press, 1987); Abraham J. Twerski, The Shame Borne in Silence: Spouse Abuse in the Jewish Community (Pittsburgh: Mirkov Publications, 1996); Abraham J. Twerski, Addictive Thinking: Understanding Self-Deception (Center City, MN: Hazelden, 1997); Yisrael N. Levitz and Abraham J. Twerski, eds., A Practical Guide to Rabbinic Counseling (Jerusalem: Feldheim, 2005), and his dozens of other works published over the past half-century, including more than fifty works at the catalog of ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications.