Tarnopol: A short-lived early 19th century Hebrew press

Tarnopol: A short-lived early 19th century Hebrew press

by Marvin J. Heller[1]

The blossoms have appeared in the land, The time of your song has arrived,

and the voice of the turtledove Is heard in our land.

The green figs form on the fig tree. The vines in blossom give off fragrance.

Arise, my darling; My fair one, come away!

“O my dove, in the cranny of the rocks. Hidden by the cliff.

Let me see your face, Let me hear your voice; For your voice is sweet And your face is comely.”

Catch us the foxes, The little foxes

That ruin the vineyards— For our vineyard is in blossom. (Song of Songs 2:12-15).

Tarnopol (Ternopol), a city with an established Jewish community, dates its founding to the mid-sixteenth century. The community had many positive aspects (blossoms have appeared in the land, The time of your song has arrived), and was home to a Hebrew printing press (The green figs form on the fig tree. The vines in blossom give off fragrance) for a brief time only in the early nineteenth century. Due, however, to the contentious relationship between conflicting segments of the community, that press, after publishing a variety of valuable works, was short lived and closed prematurely (The little foxes that ruin the vineyards).

Tarnopol is in Galicia, in the western Ukraine, approximately 227 miles (365 km.) from Kiev (Kyiv) and 73 miles (117 km,) from Lvov. Although there had been earlier residences in the area, credit for founding the city as a private town in 1540 is given to the Polish hetman, Jan Amor Tarnowski. Tarnowski permitted Jewish settlement almost immediately afterwards in what was his personal domain. The city charter permitted Jews to reside throughout the city, excluding the market place. Initially, the Jewish population was small, comprised of only a few dozen Jews, this based on the head tax paid, the revenues from it being, in 1564, 20 zlotys, rising to 23 the following year. Jews quickly became a majority of the population, with as many as 300 families resident there in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[2] By 1765, the Jewish population of Tarnopol had increased to 1,246 Jews.[3]

In 1548, Tarnopol was granted the privilege of the Magdeburgian Laws, regulations concerning internal autonomy within cities and villages granted by the local ruler, developed by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (936–973). In 1566, Tarnopol received the Emporium Right, the duty of storing the merchandise of the merchants passing through the town, and the privilege of the residents of the town to be the first to purchase the merchandise. Tarnopol was fortified and strengthened during the Tartar invasions in 1575 and 1589. In 1621, it became the property of Chancellor Tomash Zamoiski.[4]

A fire in 1623 caused significant damage to the homes in the city, but Zamoiski allowed the Jews to rebuild their homes as well as a new synagogue, this constructed in citadel style, to replace the one destroyed in the fire. Jews could buy and sell goods, excepting some leather merchandise, this to protect the monopoly of Christian shoemakers. Jews could be butchers, but had to provide the owners of the city annually with ten milk stones.

Tarnopol suffered, as did Jewish communities throughout Eastern Europe, from the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648-49 (tah ve-tat) and again in 1653 from the Tartar invasions. Until the ravages of the former occurred, the Jewish community was prosperous. At that time, however, most Jews fled, those remaining being massacred. Jews participated in the defense of the city in the Cossack and Swedish wars. The city, now the property of Alexander Konyetspolski, was reconstructed, but suffered yet again in 1672 when the town’s castles and citadels were bombarded by the Turks. Towards the end of the century the community began to revive, Jewish merchants being dominant in the grain and cattle trades.[5] In 1690, Tarnopol became the private property of the Polish royal family, Subiesky, and subsequently was transferred to the noble Polish family, Pototski, remaining in their possession until 1841 when private ownership of cities was abolished.

An early rabbi in Tarnopol was R. Gershom Nahum R. Meir ben Isaac Tarnopoler, who stated that “Our community is the capital (i.e it was important).” The rabbis active in Tarnopol in the eighteenth century included R. Joshua Heschel Babad, followed by R. Jacob Isaac ben Isaac Landau. Joshua Heschel Babad’s (Babad is an acronym of Benei Av Bet Din, “children of the av bet din,” 1754-1838) itapprobations appear in several of the titles described in this article and served as rabbi of Budzanow and, from 1801, of Tarnopol. He opposed the growing circle of maskilim in Tarnopol and polemicized against their patron, Joseph Perl (below), and, in 1813, of the teaching system in the school founded by Perl where secular studies were taught.[6]

Tarnopol suffered from an outbreak of the Black Plague in 1770, suffering many deaths. Finally, in 1772, Tarnopol was annexed to Austria and from 1809 to1815 was in the possession of the Russians, returning to Austrian rule until it became part of the Western Ukrainian Republic. Its status changed yet again at the end of 1918 when it became part of independent Poland.

In the early eighteenth century Tarnopol was largely Hassidic. Nevertheless, among the significant figures in Tarnopol was Joseph Perl, a prominent Maskil, active in that movement and an opponent of Hassidus.

A Hebrew press was established in Tarnopol in 1812. At that time Nahman Pineles and Jacob Auerbach, accomplished printers, obtained permission from the Russian authorities to establish a Hebrew press, this with the condition that the books to be printed would be approved by the censor. They acquired typographical equipment from the printer Benjamin ben Avigdor and employed two workers, Mordecai ben Zevi Hirsch and Aryeh Leib ben David. Ch. Friedberg informs that this was not an auspicious time to establish a press due to the Napoleonic wars. Nevertheless, it was established with the support of Joseph Perl, who not only provided financial assistance, but also space in his school for the press. He did so in the belief that the books published by the press would be in support of the Haskalah.[7]

The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book records twenty-two entries, from 1812-13 through 1817.[8] These works are varied. We will describe a portion of them, several in some detail, others in passing, giving a sense of the press’ output.

I

Yeshu’ot Meshiho – Printing is reported to have begun with Don Isaac ben Judah Abrabanel’s (1437-1508) Yeshu’ot Meshiho (the Salvation of His Anointed) in 1812-13.[9] Abrabanel, a noted statesman, biblical exegete, and philosopher, traced his lineage to King David. He was the grandson of Samuel and the son of Judah Abrabanel, the former an advisor to three Kings of Castile, the latter to the King of Portugal. Don Isaac Abrabanel received a thorough Jewish education, studying Talmud under R. Joseph Hayyun (d. 1497), as well as instruction in philosophy, classics, and even Christian theology, this last useful in his defense of Judaism. Abrabanel succeeded his father as treasurer to King Alfonso V of Portugal, during which time he was instrumental in redeeming Jewish captives brought to Portugal. Upon the death of Alfonso in 1481, João II (1481-95) became king of Portugal. In 1483, João accused Abrabanel of participating in a conspiracy. Forewarned, Abrabanel fled to Spain, where he served as an official in the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. In 1492, they offered him the opportunity to remain in Spain as a Jew, but he chose to go into exile and left with other Jews.[10]

A prolific author Abrabanel wrote extensive and highly regarded commentaries on books of the Bible, philosophical works, and a three-part trilogy of consolation on resurrection and redemption. Yeshu’ot Meshiho is the third part of the trilogy. The first parts are Ma’yenei ha-Yeshu’ah (Wells of Salvation), first printed in Ferrara (1551) on the book of Daniel, followed by Mashmi’a ha-Yeshu’ah (Announcing Salvation), first edition published in Salonika (1526); the trilogy is completed with Yeshu’ot Meshiho. The text addresses redemption, the Messiah, and the end of days.[11] This is recorded as the first edition of Yeshu’ot Meshiho in bibliographies, but is extremely rare and was not seen by this writer. It is recorded as an octavo.

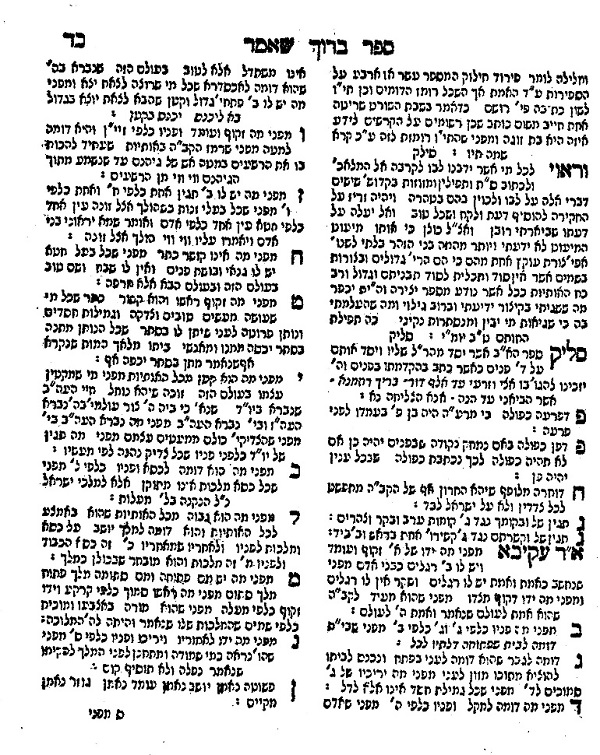

Rosh Amanah – Our second work by the Abrabanel, also printed in 1813, is Rosh Amanah, on the principles of faith. First published in Constantinople (1505) this edition was printed in the year “[From Lebanon, my bride, with me!] Trip [look] down from Amana’s peak תשורי מראש אמנה (573 = 1813)” (Song of Songs 4:8), a reference to the principles of faith (Emunah). It was printed in quarto format (40: 30 ff.). Abrabanel completed Rosh Amanah “in Naples at the end of Marheshvan, in the year, ‘The voice of rejoicing רנה (255=November, 1494) and salvation’” (Psalms 118:15), that is, two years after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. The verso of the title-page has an approbation from R. Joshua Heschel Babad, av bet din of Tarnopol, immediately below it is verses from Judah Abrabanel, the author’s son, and below that a statement that wherever the phrases akum or goi appears it refers to ancient idol worshippers, not to contemporary non-Jews who are upright people.

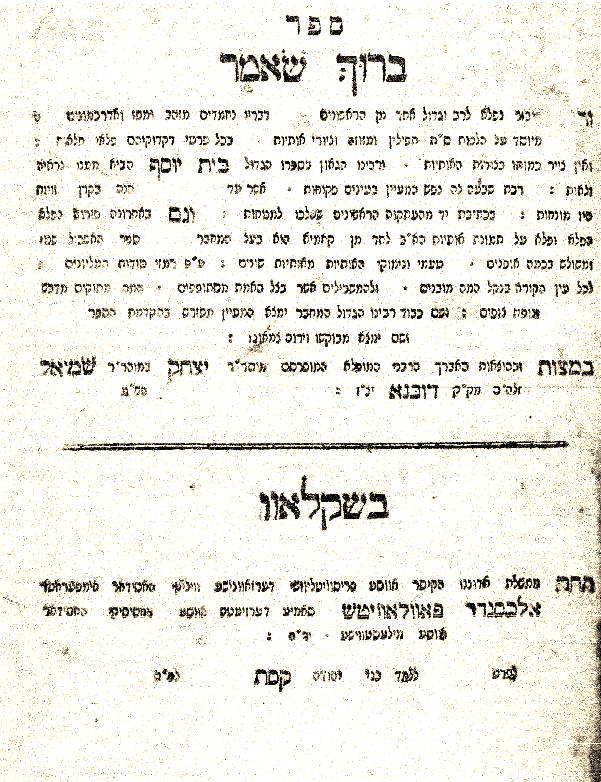

1813, Rosh Amanah

Next is Abrabanel’s introduction, in which he explains that his purpose in writing the book is twofold, to clarify the confusion resulting from the many lists on the principles of faith and to defend Maimonides from his critics, most importantly R. Hasdai Crescas (c. 1340–c. 1410–11, Or HaShem), and Joseph Albo (15th century, Ikkarim). Stylistically, Rosh Amanah follows the same format as Abrabanel’s other works, that is, he poses a series of questions which he then resolves.

There are twenty-four chapters. In the first twenty-two Abrabanel enumerates twenty-eight objections to Maimonides thirteen principles of faith, twenty taken from Crescas and Albo. Abrabanel subsequently resolves these objections, defending Maimonides from his critics, although he too, in chapter twenty-three, rejects Maimonides’ formulation of a dogma for Judaism. Rosh Amanah begins with a discussion of the thirteen principles, followed (ch. 2-5) with Crescas and Albo’s objections; then nine necessary propositions for the ensuing discussion (6-11); the refutation of the objections (12-21); criticism of Crescas’ and Albo’s formulation (22); Abrabanel’s contention that Judaism has no dogmas (23); and lastly, a discussion of the Mishnah in Sanhedrin (90a), “All Israel has a share in the world to come,” which might seem to posit a dogma for Judaism.[12]

Despite Abrabanel’s contention that Judaism has no dogmas he writes (ch 22) that if he were to, “choose principles to posit for the divine Torah I would lay down one only, the creation of the world. It is the root and foundation . . . and includes the creation at the beginning, the narratives about the Patriarchs, and the miracles and wonders which cannot be believed without belief in creation.”

Rosh Amanah has been published at least nine times to the present, excluding a questionable 1547 Sabbioneta edition, and translated into Latin by Guilielmum Vorstium (Liber de capite fidei, Amsterdam, 1638 and 1684), French by B. Mossé (Le princips de la foi, Avignon, 1884), and English twice, that is, the first five chapters by Isaac Mayer Wise (The Book on the Cardinal Points of Religion), serialized in The Israelite (Cincinnati, 1862), and more recently in its entirety as by M. Kellner (Principles of Faith, Rutherford, 1982).

Hamishah Homshei Torah – Among the other works published at this time were a Hamishah Homshei Torah, that is, a small rabbinic Bible (Mikra’ot Gedolot) with commentaries. Four volumes were published in 1813 and one volume, Bamidbar (Numbers) was published in 1814. The text of Hamishah Homshei Torah, on facing pages, is comprised of the biblical text in square vocalized letters on the right page, and below it in rabbinic letters, R. Aaron of Pesaro’s (d. 1563) Toledot Aharon, a concordance, brief citations to the places where each word or phrase in the Biblical text appear; the commentaries of Rashi; and Siftei Ḥakhamim (R. Shabbetai ben Joseph Bass, 1641-1718), a super-commentary on Rashi. On the facing page is Onkelos in square vocalized letters, the Ba’al ha-Turim (R. Jacob ben Asher, c. 1270-1340) and the continuation of Rashi and Siftei Ḥakhamim, all in rabbinic letters.

Likkuttei Shoshanah – Another very different work, published in 1813/14 is R. Samson Ostropoler of Polonnoye’s (Volhynia, (d. 1648) Likkuttei Shoshanah. Ostropoler, a kabbalist of repute, died on July 22, 1648, at the head of his community in the Chmielnicki massacres. At that time, Ostropoler assembled 300 members of his community into the synagogue and, dressed in shrouds and prayer-shawls, said selihot and prayers until they were slaughtered. R. Nathan Hannover, in Yeven Metsulah on the Chmielnicki massacres, informs that a magid (heavenly teacher) who frequently instructed Ostropoler in the secrets of the Kabbalah, warned him of the impending catastrophe, advising Ostropoler to call the community to repent, which he did but to no avail.[13] Likkuttei Shoshanah, a kabbalistic work, was published in a small format, 20 cm. (8 ff.).

II

Pa’ne’ah Raza – R. Isaac ben Judah ha-Levi’s commentary on the Torah, Pa’ne’ah Raza, built upon literal interpretations (peshaṭ) intermingled with gematriot and notarikon (numerical and abbreviated letters of words) is also an 1813 publication. Isaac ben Judah ha-Levi (13th cent.) was one of the Tosafot of Sens, and a student of R. Hayyim (Paltiel) of Falaise. Printed previously in Prague (1607), this edition was published as an octavo (80: 142, [2] ff.).

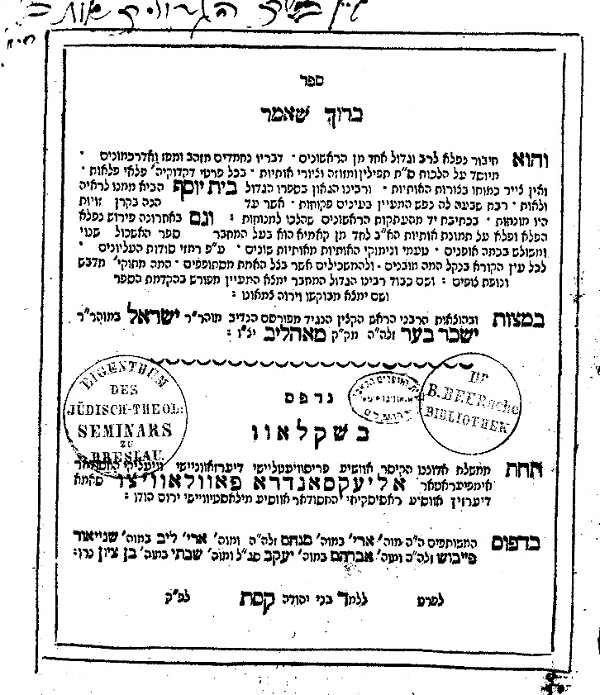

1813, Pa’ne’ah Raza

The title-page informs that the contents include, in addition to Isaac ben Judah ha-Levi’s commentary the insights of many other rishonim (early sages) who are then noted, and that Pa’ne’ah Raza, is novellae on Hamishah Homshei Torah and Megillah in veiled ways. Among the many virtues that the title-page lists are insightful forms of elucidation, all desirable, sharp, sweet peshat (literal interpretations), queries and responses, and much more. Also included are words of the sages through gematriot, as given at Sinai with sound and flame.

The title-page is followed by R. Joshua Heschel Babad’s approbation and then Isaac ben Judah’s introduction. He begins that “I am the youth of my mother’s house and of my people, ‘a worm and a maggot’ (Avot 3”1), I know my place . . . ‘I am but dust and ashes’ (Genesis 18:27).” The title alludes to his name Pa’ne’ah פענח and Raza רזא, both have a numerical value of 208, the numerical value of his name, Isaac יצחק (208). He has included what he has heard from his teachers, among them Ran, R. [Joseph] of Orleans, R. Joseph Bekhor-Shor, and some sayings of R. Judah he-Hasid, in gematriot and peshat. He also names R. Eliezer of Worms and others, stating that he has noted the name of every contributor where possible; for he does not, heaven forbid, wish to take someone else’s adornment. Where he does not know the name, it is left unspecified.

R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai (Hida, 1724-1806), notes the wonder (miracle) and foreknowledge in the heart of the author, that Pa’ne’ah Raza, the name given so many years before, standing for Isaac twice, represents both the author and, after many centuries, the editor.[14]

Although Pa’ne’ah Raza is noted for its gematriot and notarikon much of the text is literal explanations. An example is the following, from Exodus 40:35:

“And Moses was not able to enter [into the Tent of Meeting, because the cloud abode on it]. Rashi explains, “the cloud was removed and he entered and He spoke with him.” A difficulty, how if so did He speak with him. For all the days of their encampment the cloud was over it? Furthermore, if so, Aaron and his sons could not enter, in which case, how did they burn the incense, light the menorah, and arrange the lehem ha-Panim? It is possible to say that this was one (another) cloud and during the days of their encampment they were able to enter . . . and R. Eliezer of Worms explains that for one hour the cloud was on it and afterwards removed so that they could enter.

As noted above, Pa’ne’ah Raza was first published in Amsterdam in 1607. This is the third edition, followed, according to the Bet Eked Sefarim, by two additional editions, the last being Warsaw (1928). The National Library of Israel records more recent printings, the latest being Ann Arbor, Michigan (1974) and Jerusalem (2019) editions.[15]

Torat ha-Adam – A work, undated and lacking the place of printing attributed to Tarnopol, although that is uncertain, is R. Samuel ben Shalom’s Torat ha-Adam, an ethical work with kabbalistic content. It was published in c. 1813; measures 23 cm. and comprised of 28 ff.[16] At the top of the title-page is the statement, “Happy is the man who has not forgotten you, and the son of man who finds his strength in You.” The text of the title-page states that it was written by the holy man of God. All who will look into it with open eyes will see how a person has to serve the Lord with a complete and perfect service in order to acquire true completion, for this is why man was created in this world. It further informs that the author, R. Samuel ben Shalom, is a grandson of R. Moses of Ostrog, author of Arugat ha-Bosum on the Song of Songs. The title page is followed by R. Samuel’s introduction, where he writes that he entitled the book Torat ha-Adam because it is how a person should conduct himself all the days of his life in this world. Much of the text is taken from or influenced by the Mishnat Hasidim of R. Emanuel Hai Ricci.[17]

Imrei Binyamin R. Benjamin ben Meir ha-Levi of Brody’s Imrei Binyamin, discourses on the weekly Torah readings, was printed in the year “Of Benjamin he said: Beloved of the LORD, He rests securely beside Him ולבנימין[אמר] ידיד ה“ ישכן לבטח’ (574 = 1814)” (Deuteronomy 33:12). Imrei Binyamin was published as an octavo (80: [3], 92 ff.). Although the title-page describes Imrei Binyamin as being on all the weekly Torah readings the text is actually only from the beginning of Bereshit (Genesis) through be-Hukkotai (Leviticus). The title-page informs that these discourses were delivered on Shabbat by Benjamin when he was the maggid mesharim in Berdichev for seventeen years and afterwards in Brody. Imrei Binyamin was brought to press by R. Meir Eliezer ben Pinhas, the author’s grandson. He sadly begins the introduction, “I am the builder of the house of Benjamin, the father of my father.” Benjamin ben Meir had one son only, who predeceased him. In several instances, inserted between the columns of R. Benjamin’s commentary are annotations of Meir Eliezer. He hoped to publish other parts of this work but that, unfortunately, did not happen.[18]

III

Mishlei Shelomo – In 1814, the press published Menahem Mendel Lefin’s (Levin, 1749-1826) Mishlei Shelomo, a bi-lingual octavo format (80: [2], 91 ff.) Hebrew-Yiddish commentary on Proverbs. Lefin, born in Satonov, Podolia, was therefore known as Satonover, and was also referred to as Mikolayev, as he also resided in Mikolayev for an extensive amount of time; spending his last years in Brody and Tarnopol. Lefin received a traditional Jewish education, studying Talmud and rabbinic codes, but early in his life, reportedly by accident, came across and was influenced by Joseph Solomon Delmedigo’s (1591–1655) Elim, dealing with mathematics and physics, motivating him to study those subjects. Lefin subsequently went to Berlin for medical treatment where he was also influence by Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786), becoming a strong advocate of the Haskalah.

Lefin was a prolific author, his titles including a Hebrew translation of Dr. Samuel-Auguste Tissot’s popular book on medicine; and encouraged by a friendship with Prince Czartoryski, Essai d’un plan de reforme, avant pour objet déclairerhis la Nation Juive en Pologne et de la rdresser par s4es moeurs (An essay upon a Plan of Reform with the Object to Enlighten the Jewish Nation in Poland and to Improve it in Accordance with its Customs); . Lefin’s Hebrew works include Iggrot ha-Hokkmah, Refuot ha-Am, Heshbon ha-Nefesh, which, among other ethical topics, also elaborates on Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac, which R. Israel Salanter (1810-83), founder of the Mussar movement, considered an excellent handbook for moral development and had reprinted; a new translation of Maimonides’ More Nevuchim, this in Mishnaic Hebrew, and Alon More, Lefin’s only original work, this an introduction to the philosophy of Maimonides, and Mishlei Shelomo, all in “a delightful prose”.[19]

The brief text of the title-page of Mishlei Shelomo states that it includes a concise new commentary in Ashkenaz (Yiddish) for the benefit of our brothers Beit Yisrael in the lands of Poland. Below that is that it was printed with the permission of the censors. There are two approbations, the first from R. Joshua Heschel Babad, the second from R. Mordecai ben Eliezer Sender Margolious, av bet din, Satonov. Below the approbations is Lefin’s introduction, in which he notes that so Torah should not be forgotten from Israel, he has included commentators and transcribed books of the Bible into different languages. He notes that in later generations with the movements of Jews and forgetfulness, older commentaries are not always understood, particularly in the lands of Ashenaz. Therefore, he has undertaken to bring out a concise commentary for our brothers in those lands, beginning with Proverbs (Mishlei).

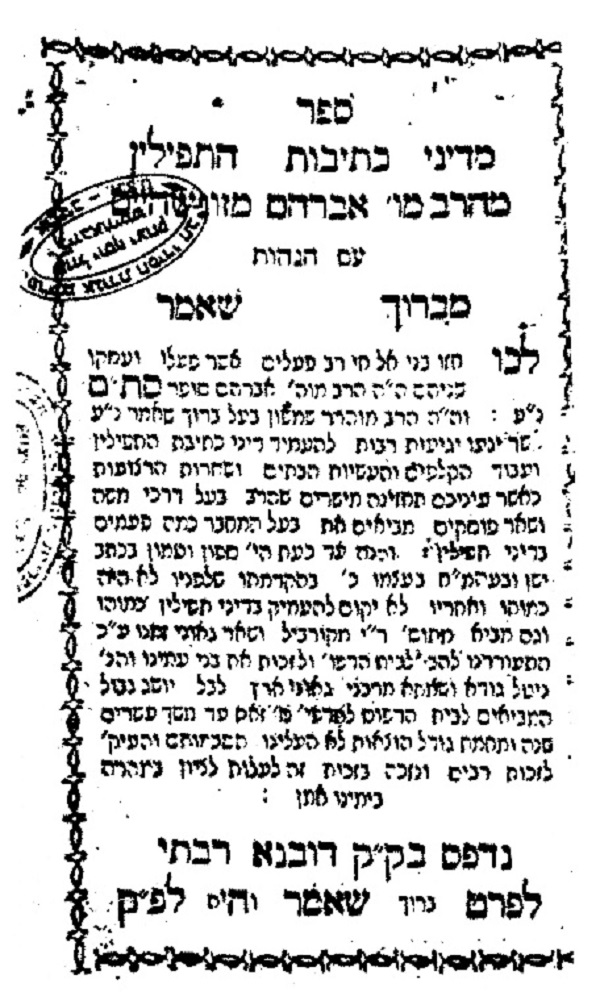

1814, Mishlei Shelomo

The text follows, comprised, on facing pages, of the text of Proverbs in vocalized square letters, below it Lefin’s commentary in rabbinic letters, on the recto page. On the verso is Lewin’s translation in square vocalized letters and below it the continuation of the commentary. Zinberg writes that Lefin disregarded the distinction between the spoken and written language, and that Ecclesiastes and Proverbs should not be translated “in the language that the market-Jewess speaks to her customer in the street.” Zinberg describes Lefin’s purpose in the translation, putting an end to the standard style of the translations of the Bible that had been dominant for hundreds of years and according to which the children in the schools had the Biblical text taught and translated to them. He wishes to give ordinary Jews , worn out with toil, the “holy books” without embroidered covers, but in the simple, weekday garment of the colloquial language, with its homely concepts and images, including its Slavisms, as it is spoken at home and in the market place. . . .Mendel Levin-Satanow did not print his translation of Proverbs in the special “women’s type” customary for Judeo-German books, but in square Hebrew letters and with vowels. Levin’s spelling is also characteristic of his translation: he writes the words mainly according to their phonetic sound. Thus we find in his work rufikh, not ruf ikh: nemtzakh, instead of nemt es aykh . . .[20]

Mishlei Shelomo was part of Lefin’s translation of the Bible into Yiddish, of which only the volumes on Proverbs and Ecclesiastes were published. He was able to publish Mishlei Shelomo with the financial aid of Joseph Perl. As noted above, Mishlei Shelomo has approbation from two av bet din. It is rare, indeed unusual, for rabbis to give approbations to books by Maskilim, especially in this case where a sponsor was Joseph Perl, who was opposed to the orthodox establishment.

Waxman observes that Lefin’s translation into the Yiddish vernacular raised the objection, “a hue and cry” among Maskilim who regarded Yiddish as a jargon and wished to reduce its use as much as possible. Tobias Gutman, another maskil, even wrote a pamphlet against Lefin, branding him a traitor to the cause of Hebrew. Leaders of the Galician Maskilim intervened and the pamphlet was not published during Lefin or Gutman’s lifetime. All of this notwithstanding, Lefin’s books were generally popular.

IV

Luach (Calendar) – Three calendars are recorded for the Tarnopol press, that is, 1813,1814, and 1815, all credited to Joseph Perl. Each calendar is octavo in format, the 1814 calendar, our subject calendar, is (80: [9], [4], 1, 11, [1] ff).

Joseph Perl (1773–1839), already noted several times in passing, was a person of import in the Haskalah. He was born in Tarnopol to Todros. a wealthy wine merchant and for a time holder of the communal concession for the tax on meat. As a young man, Perl was attracted to Hassidism, but while a partner in his father’s business he travelled to various locations where he met Maskilim, among them, in Brody, Menahem Mendel Lefin, who inspired Perl. He was deeply involved throughout his life in education, founding a moderate Haskalah school in Tarnopol, one that continued to exist until World War II. Perl served as principal of the school, which initially gave lessons in Perl’s mansion taught in German, boys learning for eight years, girls for five. An opponent of the educational system established by Perl was Joshua Heschel Babad, av bet din of Tarnopol.

1814, Luach (Calendar)

Among his activities in Tarnopol, from 1813 to 1815, was the publication of these calendars, which cited rabbinic sources and popular science. Perl became an opponent of Hassidis, which he felt had left the path of tradition, authoring several anti-Hasidic satires, beginning with Über das Wesen der sekte Chassidim (On the Essence of the Hasidic Sect), written between 1814 and 1816. Next was a Hebrew-Yiddish parody of R. Naḥman of Bratslav, entitled “The Story of the Loss of the Prince,” which mocked Hasidism. His most important work was Megaleh temirin (The Revealer of Secrets; 1819), published under the pseudonym Ovadyah ben Petaḥyah, “harshly critical of Hasidic society, its leaders, and its customs its leaders, and its customs.” Perl wrote yet additional works in the same vein.[21] The activities of Perl and his fellow Maskilim resulted in a ban on the Maskilim by the admorim R. Jacob Orenshtein of Lvov in 1816 and by R. Zevi Hirsch Eichenstein in 1822, and R. T. Israel from Rejin, nicknaming “Joseph Perl ‘the second son of Miriam’” referring to the founder of Christianity.[22]

The cover of the calendar succinctly states that it is a calendar for the year 1814 and on the verso lists the contents, that is, the calendars and other material included within the publication. This is followed by a more detailed title-page that states that it is from the year five thousand תקע”ד ([5] 574 = 1814) from the creation of the world according to the accounting of the people of Israel, followed by its contents, which include the Roman (secular) calendar, other calendars as well as other virtues such as the eastern calendar, sunset, the days (history) of the Roman state, locations where places of justice are closed, concluding that added is a luah ha-lev (heart rest) in which all who read it will find calm for his soul, and, de rigeur, with the permission of the censor.

The verso of the title-page has a list of pertinent contractions for the year 1814 and below the order of Hoshanas (prayers said on Hoshana Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot). This is followed by several charts for the molad (appearance of the new moon), chronology of historical events, additional calendars, customs, and customs pertaining to the year 1814, and then luah ha-lev which encompasses such subjects as hospitality, loving thy neighbor, loving Torah and wisdom, charity, honoring one’s parents, and much more. Next is a section entitled examining nature, with subheadings, encompassing such subjects as five things are said about a mad dog (Yoma 88), and concerning products such as grapes and olives. At the end are ethical parables and eleven riddles, for example. who is it that is born a few days after his mother; what is the easiest of all things to do, concluding that the answers will be given in the next calendar.

Shevah Tefillot – Another prayer book, attributed by some to Joseph Perl. It is a small work (15 cm., [40\] pp.), designed for the use of students. The title-page informs that it is “Shevah Tefillot: for the seven days of the week, as the young boys pray daily immediately when they come to learn in the Beit ha-Sefer (yeshivah) which exists to educate the Benei Yisrael (Jewish children) of Tarnopol). Immediately below it is like text in Yiddish. The following page has the verse “He who turns a deaf ear to instruction. His prayer is an abomination” (Proverbs 28:29). The text is comprised of facing pages of prayers for each of the seven days of the week in square vocalized Hebrew letters and in Yiddish in square unvocalized Hebrew. The National Library of Israel (NLI) attributes Shevah Tefillot to the Beit Sefer ha-Hinukh Na’arei Benei Yisrael (Tarnopol), that is the school faculty. The Thesaurus attributes Shevah Tefillot to both the Beit Sefer and Joseph Perl, in contrast to the NLI description which states that the author compiler is unknow. However, given Perl’s involvement with education in Tarnopol the attribution to Perl appears reasonable.

V

Sha’arei Ziyyon – A very different type of work, in contrast to the works of Maskilim, is R. Nathan Nata ben Moses Hannover’s (d. 1683) Sha’arei Ziyyon, a collection of Lurianic kabbalistic prayers, particularly for Tikkun Hazot (midnight prayers in remembrance of the destruction of the Temple and for the restoration to the Land of Israel). Hannover’s birthplace and early background are uncertain. His residence in Zaslav, Volhynia, was apparently peaceful and untroubled, but came to an end with the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648-49 (tah ve-tat), witnessed and recorded by him in Yeven Mezulah. He is reported to have learned Kabbalah with R. Samson Ostropoler of Polonnoye (Volhynia) who died in those massacres (above). In 1683, Hannover, then dayyan in Ungarisch Brod, was murdered while at prayers by a stray bullet fired by raiding Turkish troops.[23]

Hannover was the author of several other important works, among them Yeven Mezulah, which chronicles the experiences of Polish Jewry during the Chmielnicki massacres, based on first person accounts, first edition published in Venice (1653) and Safah Berurah, a popular four language, Hebrew-German-Latin-Italian,, glossary for conversation and as a guidebook for travelers consisting of 2,000 words (Prague, 1660). Another work, Ta’amei Sukkah (Amsterdam, 1652) is a discourse on the festival of Sukkot. Based on a sermon delivered in Cracow in 1646; the work is incomplete. Lack of funds prevented Hannover from publishing the entire work; therefore, he writes, he is publishing one discourse only. No other parts were ever published.[24]

Turning to Sha’arei Ziyyon, it was published in 1815 in a small format, as a 14 cm. sextodecimo (160: 132 ff.). The title is from “The Lord loves the gates of Zion (sha’arei Ziyyon) more than all the dwellings of Jacob” (Psalms 87:2). The title-page informs that Hannover relied on the works of R. Hayyim Vital (1542–1620), the foremost student or R. Isaac Luria (ha-Ari ha-Kodesh, 1534–1572), whose teachings were based on R. Shimon bar Yohai (mid-second century C.E.). The title-page is followed by a description of the seven sha’arim (seven gates) comprising Sha’arei Ziyyon. They are Tikkun Hazot based on Etz ha-Hayyim; Tikkun ha-Nefesh, to be said after Tikkun Hazot with Yedid Nefesh; Tikkun ha-Tefillah according to Kabbalah; Tikkun Kriat ha-Torah; Tikkun Kriat Shema with the appropriate kavvanot; Tikkun shel Erev Rosh Hodesh; and Tikkun Malkhut on Rosh Ha-Shanah and Yom ha-Kippurim. Omitted are the approbations and Hannover’s introduction that appeared in the first edition (Prague, 1682).

Text is generally in a single column in square vocalized letters, occasionally accompanied by commentary in rabbinic letters. This too is in contrast to the first edition which was in a single column in rabbinic type with occasional headers, and some limited text in square letters. Sha’arei Ziyyon is primarily a compilation of existing prayers assembled into one work. Prayers currently recited on special festival days, such as Ribbono shel Olam, said prior to the removal of the Torah from the Ark and the Yehi Ratzon after the priestly blessing are taken from Sha’arei Ziyyon

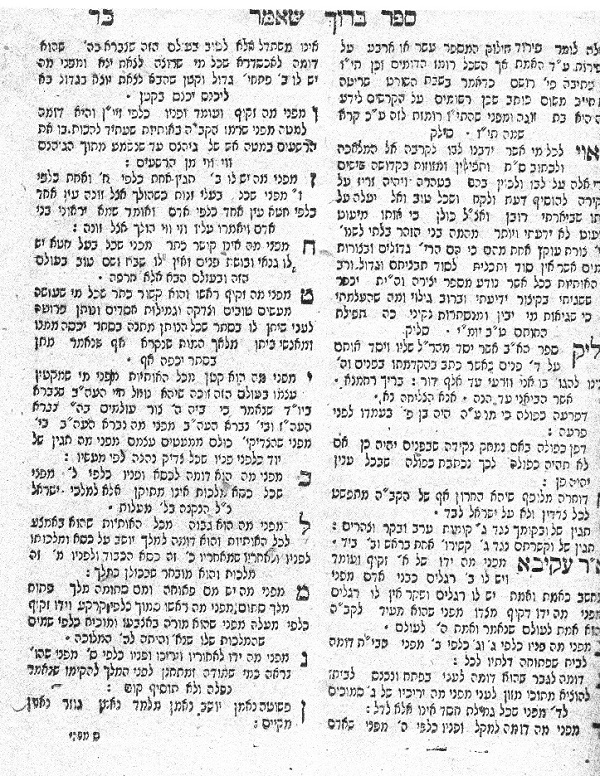

1815, Sha’arei Ziyyon

Gershom Scholem, in describing the influence of Kabbalah on Jewish life, writes that one of the areas in which it had the greatest influence was prayer. Sha’arei Ziyyon is among the most influential books in this sphere, expressing Lurianic doctrines “of man’s mission on earth, his connections with the power of the upper worlds, the transmigrations of his soul, and his striving to achieve tikkun were woven into prayers that could be appreciated and understood by everyone, or that at least could arouse everyone’s imagination and emotion.”[25] Sylvie-Anne Goldberg describes as Sha’arei Ziyyon “one of the most widely read books in the Jewish world.”[26] The Bet Eked Sefarim enumerates fifty-four editions through 1917.[27] The National Library of Israel records an additional twelve editions through 2019.

Likkutei Zevi – Another liturgical work is R . Zevi Hirsch ben Hayyim Wilhermsdorfer’s Likkutei Zevi, a varied prayer book. Published in 1815 it too is a 14 cm. sextodecimo (160: 102 ff.). Zevi Hirsch was a scholar and printer in Wilhemsdorf, active there for almost three decades, beginning to print in 1712 at the age of twenty-nine. He was the was the author of annotations to a Selihot (1714), Darkei No’am (1724) and Likkutei Zevi (1738) published by him in Wilhemsdorf, as well as Likkutei Naftali (Fuerth, 1769).[28]

The title-page notes that Likkutei Zevi has been printed numerous times and has added prayers for the shelosh regalim, on teshuvah. Likkutei Zevi begins with prayers in large square vocalized letters, followed by prayers in smaller square unvocalized Hebrew and includes material in rabbinic letters. The text is comprised of selections form Psalms, to be said on different occasions and times of the year, such as Hodesh Elul (hafares Nedarim), Rosh HaShanah, and Yom Kippur, Mishnayot for tractates Yoma and Sukkah with the commentary of R. Obadiah Bertinoro, brief halakhot for Sukkah, material on Pesah, Iggerot Teshuvah and Rabbenah Yonah’s Yesod ha-Teshuuvah. Likkutei Zevi has proved to be a popular work, Friedberg records this as the twenty-sixth edition of fifty-eight entries for that work in the Bet Eked Sepharim through 1875, and notes further editions with supplementary material.[29]

VI

We began by noting that the Tarnopol press of Naḥman Pineles and Jacob Auerbach published a variety of valuable works “blossoms have appeared in the land, The time of your song has arrived, and the voice of the turtledove, is heard in our land. The green figs form on the fig tree. The vines in blossom give off fragrance,” this despite being “short lived and closed prematurely.” The examples of the titles issued by the press encompass philosophic, Hassidic (Kabbalistic), and Maskilic works, many clearly designed to be of communal value, such as prayer books, calendars, Hamishah Homshei Torah, and Mishlei Shelomo, others reflecting the diverse composition of the community. The varied works include books by Don Isaac ben Judah Abrabanel, Samson Ostropoler of Polonnoye, Nathan Hannover, and Menahem Mendel Lefin, and Joseph Perl.

Pineles and Auerbach were partners in the press until 1814. After that Friedberg informs that Pineles was the sole printer. He suggests that as Tarnopol was part of the Russian domain the press omitted the place of printing from some title-pages in order to mislead the Austrian censor, citing Yeshu’ot Meshiho, Hamishah Homshei Torah, Imrei Binyamin, Torat ha-Adam, Pa’ne’ah Raza, and others as examples. With the exception of Torat ha-Adam and Likkuttei Shoshanah (below) all of the titles seen and reproduced here give Tarnopol as the place of printing, which supports Friedberg that Pineles printed copies with variant title-pages for different markets. The only problem with Friedberg’s examples is that Friedberg stated that he did not see the title-page of Yeshu’ot Meshiho but included it as an example of work with variant title-pages.[30]

The press ceased printing in Tarnopol in 1817 due to a boycott of the press publications by the Orthodox community for supporting the Haskalah.[31] Prior to that, according to Friedberg, on July 6, (1 Sivan) 1816, after Tarnopol had returned to Austrian rule the press published Mekor Haim (1816) as well as educational works in German. The National Library of Israel lists a small a small number of later works, such as Ibacharta Bachaim (komentarz do Szulchana Arucha) by Hayyim ben Pinchas Schachter (1838) and Ma’aseh Ninveh (Prophezeiung Obadia’s, 1848), the latter also listed by the Thesaurus. The short-lived life of the Tarnopol press and the controversy over the nature of several of its works notwithstanding, in retrospect it can be said that the Tarnopol did press publish a variety of valuable works. Given the brief life of the press and its unfortunate end we might conclude “The little foxes. that ruin the vineyards— For our vineyard is in blossom.”

1813/14 Likkuttei Shoshanah

[1] Once again, I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Eli Genauer for reading this article and for his general editorial suggestions. All images in this article are courtesy of the National Library of Israel excepting Likkuttei Shoshanah, which is courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak.

[2] Nathan Michael Gelber and Aharon Weiss. “Tarnopol,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 19, pp. 516-518; Joseph Jacobs, Schulim Ochser, Jewish Encyclopaedia, vol. 12 pp. 63-64

[3] Jonathon Meir, “”Ternopil,” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe 2 (New Haven & London, 2008), 855-56.

[4] Francine Shapiro, Project Coordinator, “Tarnopol,” Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland, Volume II (Ternopil, Ukraine), Translation of “Tarnopol” chapter from Pinkas Hakehillot Polin by translated by Shlomo Sneh with the assistance of Francine Shapiro, pp. 234-51, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00234.html. The following description of Tarnopol is based on this Pinkas.

[5] “Tarnopol,” The Encyclopedia of Jewish life Before and During the Holocaust, editor in chief, Shmuel Spector; consulting editor, Geoffrey Wigoder; foreword by Elie Wiesel II (New York, 2001), III pp. 1291-93.

[6] Joshua Heschel Babad subsequently served briefly in Lublin (1828), but was compelled to leave the city because of his dispute with the Mitnaggedim there. He returned to Tarnopol serving there for almost forty years, until 1837. In 1830, Babad became ill and, in 1838, was replaced as rabbi, by the Maskil Shelomoh Yehudah Rapoport (Shir). Babad’s responsa, Sefer Yehoshu’a (Zolkiew, 1829), on Shulḥan Arukh, was considered a basic halakhic work. (Josef Horovitz, “Babad,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. III: vol. 3: pp. 14-15; Haim Gertner, “Babad Family,”; Yivo Encyclopedia, vol. I: pp. 102-03

[7] Ch. Friedberg: History of Hebrew Typography in Poland from its beginning in the year1534 and its development to the present. . . . Second Edition Enlarged, improved and revised from the sources (Tel Aviv, 1950), 148-49 [Hebrew].

[8] Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II.(Jerusalem, 1993–95), 340-41 {Hebrew].

[9] Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography, reports that the copy he saw lacked a title-page. He attributes this to the conditions described above.

[10] Benzion, Netanyahu, Don Isaac Abravanel: Statesman & Philosopher, (Philadelphia, 1972), var. cit.

[11] Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sepharim, (Israel, n.d.), yod 1061 [Hebrew].

[12] M. Gaster, “Abravanel’s Literary Work,” in Isaac Abravanel. Six Lectures, ed. J. B. Trend and H. Loewe (Cambridge, 1937), pp. 48-49; and Menachem Marc Kellner, ed. and tr. Principles of Faith (Rosh Amanah) (Rutherford, 1982), pp. 11-50.

[13] Ada Rapoport-Albert, “Shimshon ben Pesaḥ of Ostropolye,” YIVO Encyclopedia 2: 1710.

[14] Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, Shem ha-Gedolim ha–Shalem with additions by Menachem Mendel Krengel II (Jerusalem, 1979), p. 134 pe no. 123 [Hebrew].

[15] Ch. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim, (Israel n.d.), pe 575 [Hebrew].

[16] National Library of Israel; Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, II, 340: 7. In contrast to the two previous citations Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim tav records Torat ha-Adam as Tarnopol, 1812

[17] Courtesy of Virtual Judaica.

[18] Bidspirit, Winners lot 102 (January 18, 2021). Imrei Binyamin had an estimated auction price of $300-500, price realized $130. Another copy, Moreshet lot 032 (August 26, 2020), was placed on auction, estimate $350. Not sold. Virtual Judaica (September 19, 2017), estimate $200-500, price realized $100.

[19] Meyer Waxman, A History of Jewish Literature (Cranbury, 1960), vol. III pp. 142-44; Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature translated by Bernard Martin, VI (Cleveland, 1972-78), pp. 275-280

[20] Zinberg, vol. IX, p.216.

[21] Jonatan Meir, “Perl, Yosef,” YIVO Encyclopedia, vol. 1342-44.

[22] Francine Shapiro, Project Coordinator, “Tarnopol,” Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland, p.5.

[23] Concerning Hannover see Marvin J. Heller, “R. Nathan Nata ben Moses Hannover: The Life and Works of an Illustrious and Tragic Figure,” Seforim.blogspot.com, December 28, 2018, reprinted in Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2021) pp. 256-72.

[24] Concerning other such small books published as a prospective for larger unpublished see Marvin J. Heller, “Books not Printed, Dreams not Realized,” in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 285-303.

[25] Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (NewYork, 1973), p. 193.

[26] Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, Crossing the Jabbok: Illness and death in Ashkenazi Judaism in Sixteenth through Ninteenth-Century Prague (Berkeley, 1996), p. 88.

[27] Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim, shin 2148. Given all of those editions it should be noted that the Bet Eked Sefarim does not include the Tarnopol edition, which, if it did, would be the thirty-ninth printing or Sha’arei Ziyyon.

[28] Concerning Zevi Hirsch ben Hayyim and his press in Wilhermsdorf see Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: A History of the Individual Treatises Printed from 1700 to 1750 (Brill, Leiden, 1999), pp. 118-52; Moshe N. Rosenfeld, Jewish Printing in Wilhermsdorf. A Concise Bibliography of Hebrew and Yiddish Publications, Printed in Wilhermsdorf between 1670 and 1739, Showing Aspects of Jewish Life Also seen Mittelfranken Three Centuries Ago Based on Public and Private Collections and Genizah Discoveries. With an Appendix ‘Archival Notes’ by Ralf Rossmeissl (London, 1995), var. cit.

[29] Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim, lamed 645.

[30] Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography, op. cit.

[31] Gelber and Weiss, EJ, op. cit.