Marc B. Shapiro – Clarifications of Previous Posts

by Marc B. Shapiro

[The footnote numbers reflects the fact this is a continuation of this earlier post.]

1. I was asked to expand a bit on how I know that R. Barukh Epstein’s story with Rayna Batya is contrived. In this story we see her great love of Torah study and her difficulty in accepting a woman’s role in Judaism. Certainly, she must have been a very special woman, and I assume that she was, for a woman, quite learned. When Mekor Barukh was published there were still plenty of people alive who had known her and it would have been impossible to entirely fabricate her personality. The same can be said about Epstein’s report of the Netziv reading newspapers on Shabbat. This is not the sort of thing that could be made up. Let’s not forget that the Netziv’s widow, son (R. Meir Bar-Ilan) and many other family members and close students were alive, and Epstein knew that they would not have permitted any improper portrayal. It is when recording private conversations that one must always be wary of what Epstein reports.

A good deal has been written about the Rayna Batya story, and Dr. Don Seeman has referred to it as “the only record which has been preserved of a woman’s daily interactions with her male interlocutor over several months.”[15] When challenged about the historical accuracy of Epstein’s recollections, Seeman replied “that there is no evidence to indicate that R. Epstein invented these episodes out of whole cloth.”[16]

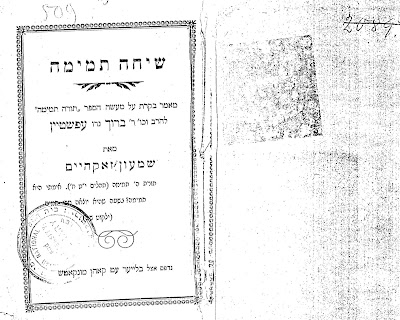

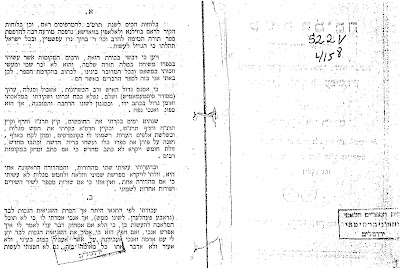

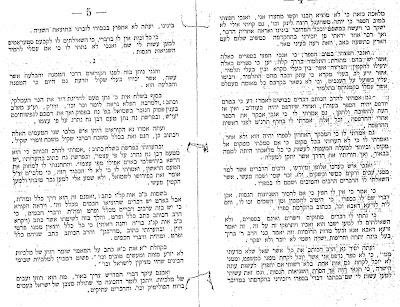

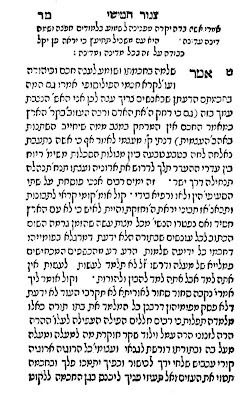

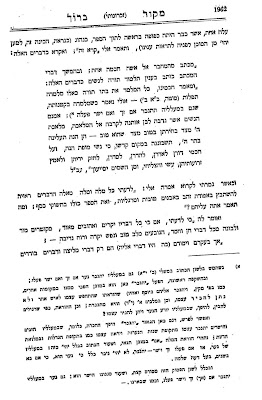

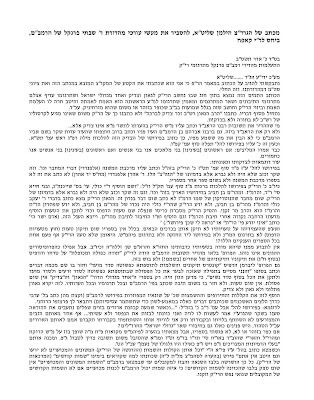

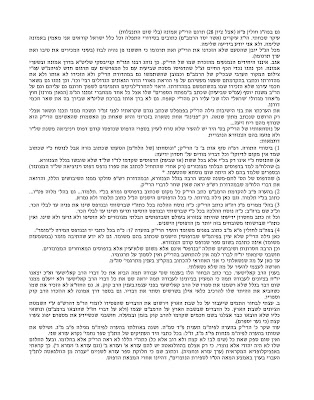

I will therefore explain how I concluded that the story is fictional. Let’s begin with the well-attested fact that Epstein was a plagiarizer. My assumption is that when dealing with someone who is not a reputable scholar, one must be very suspicious of what he or she writes when there is no outside evidence to back it up. In fact, when the Torah Temimah first appeared, the editor of this work published a booklet, Sihah Temimah, accusing Epstein of fraudulent behavior.[17] Here are the first few pages of this booklet.

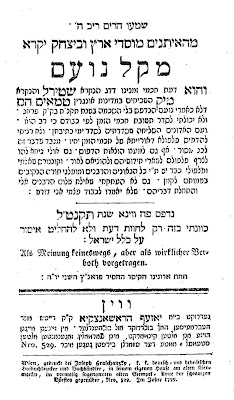

A central feature of his dialogue with Rayna Batya is her producing the book Ma’ayan Ganim by R. Samuel Archivolti. Here it states that mature women who have a desire to study Torah are to be encouraged (Mekor Barukh, p. 1962). Epstein, a young teenager, then attempts to refute her by arguing that the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim is not halakhic, but rather divrei melitzah. The whole dialogue, and in particular the part about her discovering the winning passage in Archivolti, is contrived and designed to lead the reader to sympathize with the fate of the poor woman.

A central feature of his dialogue with Rayna Batya is her producing the book Ma’ayan Ganim by R. Samuel Archivolti. Here it states that mature women who have a desire to study Torah are to be encouraged (Mekor Barukh, p. 1962). Epstein, a young teenager, then attempts to refute her by arguing that the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim is not halakhic, but rather divrei melitzah. The whole dialogue, and in particular the part about her discovering the winning passage in Archivolti, is contrived and designed to lead the reader to sympathize with the fate of the poor woman.

In his Torah Temimah (Deut. ch. 11 n. 68) he cites the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim that as a teenager he supposedly argued against. Anyone reading Torah Temimah would assume that Ma’ayan Ganim is a regular halakhic work, as Epstein refers to it as She’elot u-Teshuvot.[18]

Although at the end of the passage he says that he doesn’t know who the author is, and that Tosafot Yom Tov calls him a grammarian, I believe that this is all part of the literary game he is playing. In other words, he wants to publicize Archivolti’s view, and then to “cover” himself cites Tosafot Yom Tov. In Mekor Barukh, after telling his story, he points out that Archivolti was also a great talmudist and that the only reason the Tosafot Yom Tov refers to him as a medakdek was because he was referring to him in his youth.[19]

Dan Rabinowitz, in his discussion of the issue, writes:

The entire famous Rayna Batya incident must now be called into serious question. Was Rayna Batya so ignorant as to confuse Ma’ayan Gannim with a legitimate book of halakha? How, then, do we reconcile this with her supposed profound learning? It cannot be that R. Epstein was unable to recognize the Ma’ayan Gannim for what it was, for he himself writes that he told his aunt of the true nature of Ma’ayan Gannim. But if he did know what it was, how is it that in his Torah Temima he refers to Ma’ayan Gannim as responsa—and yet in the same paragraph in the Torah Temima he seems to backtrack and wonder how it is that the Ma’ayan Gannim could innovate “new laws about women with reason alone?” The entire Rayna Batya episode is a highly problematic one, raising one perplexing question after another.[20]

As far as the first few questions are concerned, I can only say that the entire report of Rayna Batya discovering the relevant text in Ma’ayan Ganim was made up by Epstein. This book, which was published in Venice in 1553, is an extremely rare volume. There would have only been a few copies of this book in all of Lithuania. (In Torah Temimah Epstein also says that it is a rare book.) It is therefore impossible to imagine that the rebbetzin, sitting in Volozhin, would just so happen to come across this volume on her husband’s bookshelf. Of this, there can be no doubt, and I assumed that Epstein, who was a great bibliophile, later in life came across the book and in his desire to publicize its contents, created the dialogue with Rayna Batya.

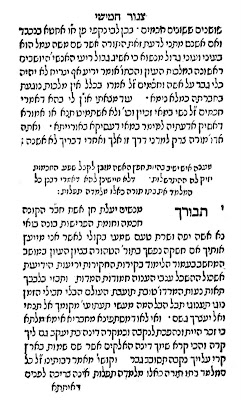

Yet thanks to R. Yehoshua Mondshine’s recent article,[21] I see that I was mistaken in my assumption. The truth is that Epstein never even saw the book and thus did not know the true nature of Ma’ayan Ganim. He learnt of the relevant passage, which he places in Rayna Batya’s mouth, from an article that appeared in Ha-Tzefirah, 7 Tishrei, 5656. We see this from the fact that the Ha-Tzefirah quotation mistakenly omits some words, and the same words are omitted in Mekor Barukh. This shows that his knowledge of this book came in 1894 and that he never discussed it with Rayna Batya, who died many years prior to this.

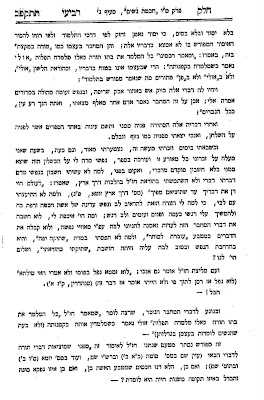

Now that we know where Epstein copied the text from, we can see another element of the literary game he played. He cites Ma’ayan Ganim as follows:

ומאמר חכמינו כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אולי נאמר כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Yet in Ha-Tzefirah it states:

מאמר רבותינו ז”ל כל המלמד בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אינה צריכה לפנים דאיתתא חזינא ותיובתא לא חזינא כי אפשר לחלק שחכמים ז”ל לא דברו אלא כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Leaving aside the words Epstein omits, he has substituted אולי for אפשר לחלק. In doing so he softened Archivolti’s point. Whereas Archivolti was stating that one can distinguish between teaching a grown woman and a small girl, Epstein has Archivolti prefacing this idea with “perhaps”. I think this is part of Epstein’s confusing game. He wants to bring this view to the public’s attention, but he doesn’t want to come off as too radical. In fact, this אולי, which is his own creation, assumes a life of its own. Thus, in his letter to R. Hayyim Hirschensohn (Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 6, p. 47), criticizing the latter’s view of teaching women Torah, Epstein writes:

In other words, Epstein invents the word אולי and inserts it into Archivolti’s letter, and then he uses this to criticize Hirschensohn! The chutzpah on Epstein’s part is astonishing, but as I see it this is all part of his game.

No one who has discussed Epstein and Rayna Batya was aware of his letter to Hirschensohn, so they could not point out the following obvious fact: When one looks at Mekor Barukh, which was published after his letter to Hirschensohn, one finds him telling Rayna Batya the exact same thing. It is obvious that he uses the language in his letter to Hirschensohn to create the following reply to Rayna Batya, that supposedly occurred some fifty years prior.

והן המחבר בעצמו כמו ‘מודה במקצת’ בזה, באמרו: ‘ומאמר חכמינו’ כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות ‘אולי נאמר כשמלמדה בקטנותה’; הרי שבעצמו אינו בטוח בדבריו, וכהוראת הלשון ‘אולי’ ולא ב”אולי” ולא ב”פן” מתירים מה שנאמר מפורש בתלמוד.

(It is possible that I am wrong in assuming that it was his positive view towards women studying Torah which explains why he created the story and cited Ma’ayan Ganim. Perhaps he was simply attempting to create a good story, or even some controversy, and that explains why he seems to be on both sides of the issue, as Dan Rabinowitz points out in the passage cited above.)

Here are the relevant pages in Ma’ayan Ganim, Ha-Tzefirah, Mekor Barukh, and Torah Temimah.

I know that there are people who are very upset at me, believing that I have given ammunition to those who chose to censor and withdraw My Uncle the Netziv. I make no apologies. We must combat falsehoods and plagiarism no matter where they emanate from. If, in the process, some of our own sacred cows are slaughtered, that is the price we must pay.

I know that there are people who are very upset at me, believing that I have given ammunition to those who chose to censor and withdraw My Uncle the Netziv. I make no apologies. We must combat falsehoods and plagiarism no matter where they emanate from. If, in the process, some of our own sacred cows are slaughtered, that is the price we must pay.

Returning to Mondshine, he is most concerned with the supposed dialogue between Epstein’s father, R. Yehiel Michel (the author of the Arukh ha-Shulhan), and the Tzemach Tzedek, R. Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. He sees it as an opportunity for Epstein to put all sorts of ideas, including criticisms of Hasidism, into the mouth of the great hasidic leader, something that if he did on his own would have brought down storms of criticism upon him. For example, he has the Tzemach Tzedek say that the hasidim have to be grateful for the opposition of the Vilna Gaon. Had it not been for the great dispute about Hasidism, and the Gaon’s strident opposition, the new movement might have led its followers out of the ranks of halakhic Judaism. (p. 1237). This idea was expressed by R. Kook (Ma’amrei ha-Re’iyah, p. 7) and was probably a common non-hasidic notion. But it is impossible to think that the Tzemach Tzedek would have ever expressed himself this way.

At the time that R. Yehiel Michel is said to have had his conversations with the Tzemach Tzedek, he was the rav of the Habad town Novozypkov.[22] In later years R. Abraham Chen and R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin served as rabbis of the town.[23] I know about this place because my grandmother’s second husband (who was like a grandfather to me) was from there. In fact, during World War One word came to the town that a certain group of Jews was being moved and would be passing through, and that among them was an outstanding young scholar named Shlomo Yosef Zevin. The townspeople came up with the necessary money to remove him from the group. He was chosen as the town’s rabbi and lived in my step-grandfather’s house for about six months. I read somewhere that the townspeople were followers of Kopys/Bobruisk, rather than Lubavitch. As R. Zevin was himself a Bobruisker, this would make sense. R. Yehiel Michel was himself born in Bobruisk, as was his son R. Baruch.

I always tell this story to Habad people in order to impress them with my yichus, that the great R. Zevin lived in my family’s house. Yet on two separate occasions after I told the story to young Habad shluchim, they replied, “Who is Rav Zevin?” It is also very rare to find a young Habadnik who has even heard of Kopust/Bobruisk. Yet without knowing about this it is impossible to understand how R. Zevin could have been a Zionist when the Lubavitcher rebbes were all anti-Zionist. After all, who ever heard of a hasid not following his Rebbe? The answer is that all Lubavitchers were Habad, but not all adherents of Habad were Lubavitch. The ignorance among some in Habad of their own movement probably shouldn’t surprise me, as I have met many hasidim who don’t have a clue about the history of the hasidic movement. And of course, how many Modern Orthodox know the first thing about Hirsch and Hildesheimer?

Mondshine assumes that one of the purposes of Epstein’s stories about his father and the Tzemach Tzedek is to build up his father’s halakhic reputation. His pesakim were subject to attack as being too liberal, and certainly in the hasidic world he was not accepted. In the Lithuanian world he was a much more important posek, and R. Joseph Elijah Henkin stated that in a dispute between the Mishneh Berurah and the Arukh ha-Shulhan, the Arukh ha-Shulhan is to be preferred.[24]

Yet many did not share R. Henkin’s viewpoint. A number of years ago I saw in one of R. Yitzhak Ratsaby’s books that he heard from some gedolim that one should not rely on the Arukh ha-Shulhan. I wrote to him objecting to this lack of respect for the Arukh ha-Shulhan, and also expressing my near certainty that the gedolim he referred to must have been Hungarian, for the Hungarian poskim never accepted the Arukh ha-Shulhan as an authoritative work. On Nov. 22, 1990, Ratsaby wrote to me:

בענין הגאון בעל ערוך השולחן, דוקא הדברים נובעים מליטא, והנני מפרש, הגר”י כהנמן זצ”ל מפוניביז’ (כמדומני שלמד בעצמו יחד עם הערוה”ש) והגר”ח גרינמן שליט”א בן אחותו של החזו”א. זכורני אמנם באגרות משה במקום אחד כתב על ערוה”ש כבר הורה זקן, ובמקום אחר דוחה דבריו. נראה לענ”ד אמנם שבעל ערוה”ש מחדש הרבה סברות ובזה כחו גדול, מאידך בעל משנ”ב מעמיק בעיון היטב הדק. והאמת ניתנה להיאמר שבהרבה מקומות בערוה”ש ראיתי דברים מתמיהים והיפך כוונת הדברים, וכבר הערתי עליו בדרך כלל במקומות שעסקתי בהם בחבורי הנדפסים. ופוק חזי שבישיבות לומדים בקביעות ההלכה מספר משנ”ב, וגם כמעט אין בית היום אשר אין שם משנ”ב. והחזו”א אעפ”י שחולק בהרבה מקומות על המשנ”ב, מ”מ החשיב אותו כהוראה מפי הסנהדרין ומנה אותו בנשימה אחת עם מרן הב”י והמג”א.

(Ratsaby’s recollection is correct. In Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim vol. 1 no. 39, which is his famous responsum on the proper height of a mehitzah, R. Moshe quotes the Arukh ha-Shulhan and uses the expression כבר הורה זקן. Regarding R. Joseph Kahaneman, he actually received semikhah from R. Yehiel Michel.)

The reputation of the Arukh ha-Shulhan has today fallen to such an extent that in a recent publication of the work the rulings of the Mishneh Berurah are included as well. The message of this is that while the Arukh ha-Shulhan is a Torah volume that should be studied, in terms of practical pesak it is the Mishnah Berurah that must be followed. See here for an earlier discussion at the Seforim blog of the recent reprint of the Arukh ha-Shulhan.

2. I was asked if there are any medieval poems in which there is explicit homosexuality. I am unaware of any, and it is precisely because they are ambiguous that there has been controversy about their meanings. This poem by Moses Ibn Ezra is as explicit as I could find

תאות לבבי ומחמד עיני

עופר לצדי וכוס בימיני

רבו מריבי ולא אשמעם

בוא הצבי, ואני אכניעם

וזמן יכלם ומות ירעם

בוא, הצבי, קום והבריאני

מצוף שפתך והשביעני

למה יניאון לבבי, למה

אם בעבור חטא ובגלל אשמה

אשגה ביפיך אד-ני שמה

אל יט לבבך בניב מענני

איש מעקשים, ובוא נסני

נפתה, וקמנו אלי בית אמו

ויט לעול סבלי את שכמו

לילה ויומם אני רק עמו

אפשט בגדיו ויפשיטני

אינק שפתיו וייניקני

כאשר לבבי בעיניו נפקד

גם עול פשעי בידו נשקד

דרש תנואות ואפו פקד

צעק באף, רב לך, עזבני

אל תהדפני ואל תתעני

אל תנף בי, צבי, עד כלה

הפלא רצונך, ידידי, הפלא

ונשק ידידך וחפצו מלא

אם יש בנפשך חיות, חיני

או חפצך להרג, הרגני

Desire of my heart and delight of my eyes –

A fawn beside me and a cup in my hand!

Many admonish me, but I do not heed;

Come, O gazelle, and I will subdue them. Time will destroy them and death shepherd them. Come, O gazelle, rise and feed me With the honey of your lips, and satisfy me.

Why do they hold back my heart, why? If because of sin and guilt, I will be ravished by your beauty – God is there! Pay no attention to the words of my oppressor, A perverse man – come and try me!

He was enticed and we went up to his mother’s house, And he gave his shoulder to my burden. Night and day I was only with him. I undressed him, and he undressed me; I sucked his lips and he sucked mine.

When I left my heart as a pledge in his eyes, The burden of my guilt was also weighted in his hand. He sought enmity, and inflicted his anger, And angrily cried, “Enough; leave me! Do not force me, and do not entice me.”

Do not be angry with me, gazelle, to destruction – Extraordinary is your will, my dear, extraordinary! Kiss your beloved and fulfill his desire. If it is in your soul to give life, revive me – Or if your desire is to kill, kill me![25]

3. When dealing with problematic texts of recent times, the preferred approach is simply to censor them. But with the medievals, there is a simpler method: Say that the text was written by a mistaken student, or even worse, by someone interested in undermining Judaism. In a previous post I mentioned that R. Joseph Zvi Duenner even stated so with regard to the Talmud itself.[26]

Since in modern times we don’t generally have students copying their master’s handwritten texts, the first approach doesn’t make much sense. Yet in a previous post at the Seforim blog,[27] I noted that R. Menasheh Klein used this very argument with regard to R. Moshe Feinstein, even though he was dealing with a responsum published in R. Moshe’s own lifetime. I found another example where Klein uses this exact same approach. He saw something in one of the Steipler’s books, but since it didn’t make sense to him, Klein wrote to the Steipler as follows (Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 7, p. 142a):

היות כי אני מכיר את מעכ”ק וצדקתו נגמר בדעתי שבודאי לא יצאו דברים מפי כ”ק או שיש שם איזה טעות בדפוס מהבחור הזעצער וטעה מעתיק ולא שם על לב כ”ק.

However, here I don’t think Klein should be taken literally. I believe this was just his respectful way of saying that the Steipler was wrong. This is not the case with regard to R. Ovadiah Yosef when he writes that one cannot rely on the responsa in R. Ben Zion Abba Shaul’s Or le-Tziyon, vol. 2.[28] Even though R. Ben Zion was alive, R. Ovadiah claimed that he was powerless to stop his students from taking liberties with the book: הוסיפו וגרעו כפי שעלה בדעתם, וסברו שכן דעת רבם. Not surprisingly, one of R. Ben Zion’s students responded very strongly to this statement.[29]

Prof. Yaakov Spiegel, in his book Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri: Ketivah ve-Ha’atakah, pp. 244ff., discusses the phenomenon of denying the authenticity of responsa. Sometimes the strategy used to reject a responsum is to attribute it to an “erring student.” While on occasion there are scholarly reasons for this assumption, it is almost always the case that the author simply cannot accept that an earlier authority said something. Usually this has to do with halakhah, but there are plenty of examples in theology. For example, R. Issachar Baer Eylenburg assumes that while resurrection is a principle of faith, one is not obligated to believe that this doctrine is found in the Torah. As he puts it (Be’er Sheva to Sanhedrin 90a).

מי שמודה ומאמין על פי הקבלה בתחית המתים אע”פ שהוא אומר דלא רמיזא באורייתא אין ראוי לקראו כופר חלילה ויש לו חלק לעוה”ב.

Although the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1, includes the point that one must believe that resurrection is found in the Torah, Eylenburg assumes that this is a textual error, and indeed, Rambam never mentions this. However, Rashi had this text and explains:

שכופר במדרשים דדרשינן בגמרא לקמן מנין לתחיית המתים מן התורה ואפילו יהא מודה ומאמין שיחיו המתים אלא דלא רמיזא באורייתא כופר הוא הואיל ועוקר שיש תחיית המתים מן התורה מה לנו ולאמונתו וכי מהיכן הוא יודע שכן הוא הלכך כופר גמור הוא.

Eylenberg didn’t like what Rashi said, i.e., it didn’t make sense to him, so he concluded:

לפי דעתי לא יצאו דברים אלו מפה קדוש רש”י אלא איזה תלמיד טועה פירש כן בגליון ונכתב בפנים.

Eylenberg would have been happy to learn what we now know, namely, that the commentary to Perek Helek is, in large measure, not really by Rashi.

I found another example of this in a book that just appeared, R. Menasheh Matloub Sutton’s Mateh Menasheh. (Sutton, who died in 1876, was the rav of Safed.) The second part of the book is a reprint of Sutton’s earlier published Kenesiah le-Shem Shamayim. This work is devoted to a superstitious practice whereby women would burn incense to demons and this was thought to be a help to people who were in various states of distress (e.g., sick, barren, etc.) He includes letters from many great rabbis who agree with him that this is a form of avodah zarah. The problem he has, which he confronts in ch. 2, is that one of the rishonim, R. Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani, is quoted by R. Hayyim Benveniste as follows:

ונראה בעיני המתוק שעושים הנשים מדבש וחלב לרפואה, וכן העישון שמעשנים מותר, שלא חייבה תורה בבעל אוב אע”פ שמקטר לשד אלא מפני שמעלה המת, וכן מעשה כשפים לא נאסרו אלא כשעושים מעשה או כשאוחזים את העיניים כמ”ש, אבל בעישון ומתוק אין בהם כל אלה, וגם אין בהם משום חובר חבר שאינם מתכונים לחבר השדים אלא לרצותם על רפואת החולה ושלא יזיקוהו.

Now it is certainly possible for Sutton to reject R. Isaiah, but it becomes very hard to label the practice as nothing less than idolatry when an outstanding rishon justified it and this rishon is also quoted by Benveniste and the Shiltei Giborim. What to do in such a case? Sutton adopts the tried and true method of declaring that since the position is (in his mind) so objectionable, R. Isaiah could never have said such a thing. It must originate with the “mistaken student” who often makes his appearance when a strange opinion is confronted.

אמינא בקושטא דמלתא כד ניים ושכיב רב אמרה להא שמעתא ועל הרוב שלא יצאו דברים הללו מתחת ידו וקולמוסו אלא שאיזה תלמיד טועה כתבם בגליון קונטריסו והרב שלטי הגבורים אגב ריהטא העתיקם בשמו ובחושבו דתורה דיליה היא מוצאת מעמו ולא פנה לעיין בעיקר הדין נמוקו וטעמו.

Sutton’s book was put out by one of his descendants, Rabbi Harold Sutton, who was a student in the late and much lamented Beit Midrash le-Torah (BMT) together with me. He later went on to become a student of R. Ovadiah Yosef, whose haskamah (together with that of R. Meir Mazuz) adorns the book.

Harold Sutton should not be confused with another young Syrian rabbi, David Sutton. The latter is the author of the ArtScroll book Aleppo: City of Scholars (and from the introduction I learned that he is a son-in-law of R. Nosson Scherman). Zvi Zohar has recently written a very sharp critique of this book. See here.

David Sutton is also the one who delivered the much-talked about lecture “We Believe in Midrashim.” This lecture is the subject of a very harsh attack by Roni Choueka in Hakirah 4 (2007). Choueka sees Sutton’s lecture as a bizayon ha-Torah of the worst sort. When listening to it I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry. How else is one to respond when one hears a rabbi claim that the fossils are remnants of the giant pets that belonged to Og, who was 800 feet tall and lifted up a stone the size of Manhattan, or that the polar bears came to Egypt complete with their blocks of snow in order to devour the Egyptian children?

Incidentally, in speaking of the Aggadah which describes the great height of Og, the Rashba (commentary to Berakhot 54b) notes that although there is a deep meaning conveyed in this Aggadah, the form in which it is expressed also had a very practical application:

לעתים היו החכמים דורשים ברבים ומאריכים בדברי תועלת והיו העם ישנים, וכדי לעוררם היו אומרים להם דברים זרים לבהלם ושיתעוררו משנתם.

In other words, in order to prevent people from dozing off, the Aggadist would convey his message with outlandish statements. R. Zvi Hirsch Chajes elaborates on this in his Introduction to the Talmud, ch. 26.

4. I have to thank those who have written to me calling my attention to things I did not know. I hope to acknowledge all of you at the proper time. However, many people who send me things have misinterpreted the sources (or the sources they send have been in error).

In the forward of H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver’s translation of Ibn Ezra to Deuteronomy, p. xiv, the following appears:

It should also be noted that I.E. [Ibn Ezra] was not the only medieval rabbi who believed that there are some glosses or slight changes in the text of the Torah. Thus Rabbi David Kimchi (c. 1160-1235) notes that the word Dan in Gen. 14:14 is post-Mosaic. He argues that the original reading of Gen. 14:14 was “and pursued as far as Leshem.” Rabbi Kimchi maintains that after the tribe of Dan conquered the city of Leshem and changed its name to Dan (Josh. 19:47), the reading of Gen. 14:14 was changed to read “and pursued as far as Dan” as in our texts of Scripture (Radak on Gen. 14:14).

The mention of “Dan” in Gen. 14:14 is used by all critical biblical scholars to prove that the verse must be post-Mosaic. The reason is that since the city would only be conquered in the days of Joshua, and only then be given the name Dan, how could the Torah refer to it this way? Even M. H. Segal, the strong defender of Mosaic authorship, acknowledges the problem. Unlike other scholars he assumes that the verse as a whole is Mosaic. But he also believes that the name “Dan” is a “modernized substitute for the antiquated names Laish or Leshem (Jud. viii, 29, Jos. xix, 47) which stood in the original.”[30]

Yet I was skeptical of what Strickman and Silver wrote as I was aware of Radak’s introduction to his Torah commentary where he is emphatic that the entire Torah is of Mosaic authorship.[31] I looked up Radak to Gen. 14:14 and saw that my skepticism was warranted. Here are Radak’s words:

וירדף עד דן: על שם סופו, כי כשכתב משה רבינו זה לא נקרא עדיין כן, אלא לשם היה נקרא וכשכבשוהו בני דן קראו לו דן בשם דן אביהם.

All Radak says is that the Torah refers to the place as Dan in anticipation of what it will be called in the future. Radak says nothing about the original reading of the Torah being “Leshem” and nothing about the text being changed after Leshem was conquered. As such, Radak cannot be added to the list of those who believe that there are post-Mosaic additions in the Torah.

5. In response to my earlier post at the Seforim blog discussing the meaning of ס”ט, Rabbi Yitzhak Oratz called my attention to Kitvei Ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan, pp. 50-51. In an 1892 letter from R. Yehiel Michel Epstein to R. Hayyim Hezekiah Medini, the author of the Sedei Hemed, we see that R. Yehiel Michel doesn’t know what the acronym stands for, as he writes חכם חיים חזקיאו [!] ס”ט הי”ו. Since the last two acronyms basically mean the same thing one would not put them next to each other, and he must have assumed that the first one meant sefaradi tahor. Yet by 1896 he had learned what it meant and he addresses the Sedei Hemed as מוהר”ר חכם חיים חזקיאו מודיני סופ”י טב טבא הוא וטבא ליהוי.

This is a rare example of an Ashkenazi who knows what the acronym means. For those who have not yet been convinced there is not much more I can say other than that there is a living tradition among the Sephardic scholars for hundreds of years now as to the proper meaning. This is certainly authoritative. Let me also call attention to the end of the introduction of the Peri Hadash on Yoreh Deah (found in the new Machon Yerushalayim edition). He signs his name as follows: חזקיה בן לא”א איש צדיק תמים היה בדורותיו דוד די סילוה נ”ע סופיה טב טבא הוא וטבא להוי אמן.

Also, see R. Yehudah ben Attar’s haskamah to R. Hayyim Ben Attar’s Hefetz Hashem (Amsterdam, 1732). R. Yehudah signs his own name סיל”ט. It is obvious that this is an alteration of ס”ט and means סופיה יהא לטב.  6. Some want to know if any of the letters Chaim Bloch published in Dovev Siftei Yeshenim are authentic. I haven’t carefully investigated every letter, so it is possible that a couple of them are also found in other books. If that is the case, then Bloch included them simply to give the work as a whole a sense of authenticity. There is, however, no doubt that everything that appears for the first time in the work is, in its entirety, a creation of Bloch. Interestingly, when Bloch sent the first volume to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe immediately recognized that the letters from the Rogochover were forged. He wrote to Bloch (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 69):

6. Some want to know if any of the letters Chaim Bloch published in Dovev Siftei Yeshenim are authentic. I haven’t carefully investigated every letter, so it is possible that a couple of them are also found in other books. If that is the case, then Bloch included them simply to give the work as a whole a sense of authenticity. There is, however, no doubt that everything that appears for the first time in the work is, in its entirety, a creation of Bloch. Interestingly, when Bloch sent the first volume to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe immediately recognized that the letters from the Rogochover were forged. He wrote to Bloch (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 69):

כן מאשר הנני קבלת הס’ “דובב שפתי ישנים”. ולאחרי בקשת סליחתו נצטערתי על שצויין על כמה מכ’ שהם להגאון הרגצובי – וכל הרגיל בסגנונו יראה תיכף שאינו . . .

The three dots are from the publisher, and I would be very interested to know what was taken out.

Bloch wrote to the Rebbe to defend his publication and the Rebbe responded very strongly. He tells Bloch that originally he thought that it was an innocent error or perhaps someone had misled Bloch as to the Rogochover’s letters. It now surprises him that Bloch continues to earnestly defend their authenticity. The Rebbe is so convinced that they are forgeries that he writes (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 159):

I assume that the Rebbe didn’t know that Bloch forged the letters himself, or that the rest of the collection was also forged. If he did know this, then I don’t think he would have been so polite to Bloch. He either wouldn’t have engaged in correspondence with him, or he would have told him that he is a liar and a scoundrel. Instead, after explaining why the Rogochover couldn’t have written the letters, the Rebbe concludes:

ואתו הסליחה על ביטוים אלו, שאולי אינם דיפלומטים ביותר.

One certainly doesn’t need to speak “diplomatically” to frauds, so I would assume that the Rebbe wasn’t aware of the extent of Bloch’s deception.

While on the topic of Bloch (who was previously mentioned at the Seforim blog [32]) I should note that his last Hebrew publication was Ve-Hayah Mahanekha Kadosh (New York 1965), which is directed against R. Moshe Feinstein’s permission for a married woman to be artificially inseminated from a non-Jewish donor. Bloch also wrote to R. Moshe about this, harshly rebuking him for this ruling. R. Moshe’s response (Iggerot Moshe, Even ha-Ezer vol. 2 no. 11) includes the following, which became one of the most famous passages in the Iggerot Moshe:

הנה קבלתי מכתבו הארוך מאד המלא דברי תוכחה על כל גדותיו על מה שלפי דעתו נדמה לו שתשובותי סימן י’ וסימן ע”א מספרי אגרות משה על אה”ע יגרמו איזה פרצה בטהרת וקדושת יחוס כלל ישראל. וניכר ממכתב כתר”ה שהיה סבור שיהיה לי קפידא על דברי התוכחה שלו, ואני אדרבה אני נרגש מזה שאני רואה שנמצאים אנשים בעלי רוח שאינם יראים ולא מתביישים מלומר תוכחה. אבל האמת שאין בדברים שכתבתי ושהוריתי שום דבר שיגרום ח”ו איזה חלול בטהרת וקדושת ישראל אלא תורת אמת מדברי רבותינו הראשונים, והערעור של כתר”ה על זה בא מהשקפות שבאים מידיעת דעות חיצוניות שמבלי משים משפיעים אף על גדולים בחכמה להבין מצות השי”ת בתוה”ק לפי אותן הדעות הנכזבות אשר מזה מתהפכים ח”ו האסור למותר והמותר לאסור וכמגלה פנים בתורה שלא כהלכה הוא, שיש בזה קפידא גדולה אף בדברים שהוא להחמיר כידוע מהדברים שהצדוקים מחמירים שעשו כמה תקנות להוציא מלבן. ואני ב”ה שאיני לא מהם ולא מהמונם וכל השקפתי הוא רק מידיעת התורה בלי שום תערובות מידיעות חיצוניות, שמשפטיה אמת בין שהוא להחמיר בין שהוא להקל. ואין הטעמים מהשקפות חיצוניות וסברות בדויות מהלב כלום אף אם להחמיר ולדמיון שהוא ליותר טהרה וקדושה.

7. Since I mentioned some stories from Halakhic Man that show that the Rav did not have a Modern Orthodox ethos, I will also say something about the following story, which some have wondered about.

Once my father entered the synagogue on Rosh Ha-Shanah, late in the afternoon, after the regular prayers were over, and found me reciting Psalms with the congregation. He took away my Psalm book and handed me a copy of the tractate Rosh Ha-Shanah. “If you wish to serve the Creator at this moment, better study the laws pertaining to the Festival.”

I understand that some people are very troubled by this story, as it bespeaks a real intellectual elitism. Yet, to use an expression popular among the younger generation, I can only say “get over it” (or become an adherent of one of the non-intellectual branches of Hasidism). For better or worse, traditional Judaism has always been a fundamentally elitist religion, dividing the haves (i.e., those who have knowledge) from the have-nots. (Although today we are accustomed to think in terms of bringing Torah study to all, in a future post at the Seforim blog I hope to mention some sources that speak of the danger of allowing the ignorant access to Torah knowledge.) Precisely because we have a notion of ein am ha-aretz hasid we can understand why, in contrast to Christianity, we don’t have women “saints” in our history. Since women have (until recent times) been kept ignorant of Talmud and halakhah, there was no way they could achieve any renown in the area of saintliness.

Regarding the passage from Halakhic Man quoted above, the Rav himself makes reference to R. Chaim of Volozhin’s Nefesh ha-Hayyim, and the ideology of that book is the basis for the Soloveitchik approach. In Nefesh ha-Hayyim 4:2 R. Chaim writes

הרי שהעסק בהלכות הש”ס בעיון ויגיעה הוא ענין יותר נעלה ואהוב לפניו יתברך מאמירת תהלים.

Yet I must also note that one needn’t be a Litvak to have this approach. Here is what R. Eliezer Papo writes (Pele Yoetz, s. v. yediah):

וכבר כתבו הפוסקים שמי שיוכל לפלפל בחכמה ולקנות ידיעה חדשה ומוציא הזמן בלימוד תהלים וזוהר וכדומה לגבי דידיה חשיב בטול תורה.

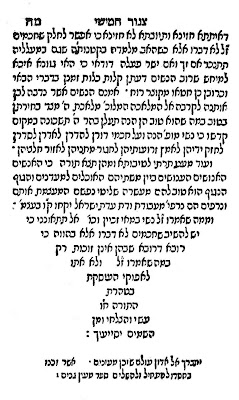

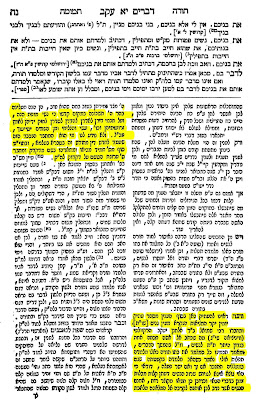

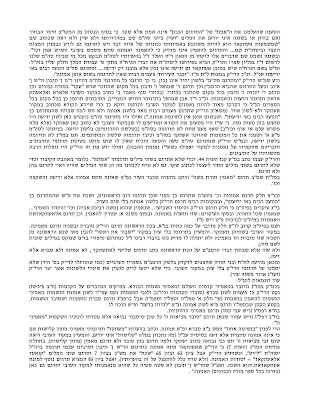

8. Many people have written to me about Ibn Ezra and post-Mosaic verses, a subject I dealt with in The Limits of Orthodox Theology. Let me therefore point out something in this regard that appears in One People, Two Worlds by Yosef Reinman and Ammiel Hirsch. As I am sure everyone recalls, this was the joint work by the Orthodox Reinman and the Reform Hirsch. What made this so significant is that Reinman is from Lakewood and never before had anyone from that community engaged in such a religious dialogue. The response was fast and furious, and here are the first three pages and the last page of an anonymous attack on him that appeared in Lakewood.

In fact, One People, Two Worlds is much worse – or much better, depending on your outlook – than anything done in this area by the Modern Orthodox. The Modern Orthodox who were part of organizations like the Synagogue Council of America and the N.Y. Board of Rabbis never engaged in interdenominational theological dialogue on an equal footing the way Reinman does. Furthermore, it is shocking that a haredi would have co-authored this book for another reason: What will happen if someone reads the book and is more convinced by the Reform rabbi? One would think that this would make the book a possible stumbling block.

In fact, One People, Two Worlds is much worse – or much better, depending on your outlook – than anything done in this area by the Modern Orthodox. The Modern Orthodox who were part of organizations like the Synagogue Council of America and the N.Y. Board of Rabbis never engaged in interdenominational theological dialogue on an equal footing the way Reinman does. Furthermore, it is shocking that a haredi would have co-authored this book for another reason: What will happen if someone reads the book and is more convinced by the Reform rabbi? One would think that this would make the book a possible stumbling block.

I have not read the book cover-to-cover, yet the word on the street is that the debate is pretty one-sided as the Reform rabbi is out of his league. But in glancing through the book I found that in one area it is actually the Reform rabbi who is correct. On p. 16 Hirsch refers to Ibn Ezra’s commentary to Gen. 12:6 and states that Ibn Ezra’s “secret” is a hint to his belief that the verse is post-Mosaic. On pp. 23-24 Reinman writes:

I do not understand how you can represent Ibn Ezra, the illustrious Orthodox commentator, as a closet Reformer. I personally have no idea of the nature of Ibn Ezra’s secret; he has successfully concealed it from me. But be that as it may, how can you ascribe non-Orthodox beliefs to Ibn Ezra? What about all the thousands of pages of solid Orthodox commentary he wrote? Don’t they stand for anything? You obviously need to connect to the time-hallowed texts, but you are grasping at the wind.

They go over this issue a couple of more times and Reinman’s responses are similarly dogmatic. Had Hirsch read my article on the Thirteen Principles (my book hadn’t yet appeared) he could have pointed out that plenty of “Orthodox” commentators and scholars have read Ibn Ezra exactly as Hirsch explained. In other words, it was incorrect for Reinman to respond as if Hirsch was asserting an outrageous canard against an “illustrious Orthodox commentator.”

When I saw this I asked a friend, who studied in Lakewood for many years, if is it possible that Reinman, who has been learning Torah for many decades, is completely ignorant about something that every YU student who takes Intro. to Bible learns in the first few weeks. His reply was that this is exactly the case, and that until he started reading works outside of the typical yeshiva curriculum he too never heard about an issue with Ibn Ezra and post-Mosaic additions. In fact, I would assume that R. Moshe Feinstein also never heard of it, and in his attack on the commentary of R. Yehudah he-Hasid he ironically cites Ibn Ezra condemnation of Yitzchaki’s biblical criticism. (Why Ibn Ezra would condemn Yitzchaki for suggesting that some verses are post-Mosaic, when he does that himself, is explained by R. Joseph Bonfils in his Tzafnat Paneah: Ibn Ezra was willing to accept individual verses as being post-Mosaic but not entire sections, which is what Yitzchaki is referring to. Thus, there is no Documentary Hypothesis in Ibn Ezra’s writings.)

This phenomenon, of great scholars not being aware of things that most people reading the Seforim blog learned years ago, should not surprise us. The traditional yeshiva curriculum is very narrow, and you can spend your life in a yeshiva and unless motivated to expand your horizons, will have no knowledge of entire areas of Jewish thought and history. A good example[33] is seen in this announcement by Agudas ha-Rabbonim, which appeared in Ha-Pardes, November 1975.  Yet the beautiful saying which the learned rabbis assume was stated by Hazal was actually stated by Ahad ha-Am, and is perhaps his most famous saying (although the concept can be found in traditional sources, see Taz, Orah Hayyim 267:1)[34] However, for one whose only Jewish knowledge comes from the yeshiva, this information would be unknown, and it is easy to see how such a statement (“more than the Jews have kept the Sabbath the Sabbath has kept the Jews”) could “infiltrate” this closed world and become just another ma’amar hazal.[35] It reminds me of how when I was a kid and my friends and I went to Boro Park for Shabbatons we would have been able to hum niggunim which came from popular songs and commercials, and our hosts wouldn’t have known a thing. At the Rutgers Chabad house in the 1980’s they even had a niggun to the tune of the theme song for Bumble Bee tuna. For those too young to remember it, see it here.

Yet the beautiful saying which the learned rabbis assume was stated by Hazal was actually stated by Ahad ha-Am, and is perhaps his most famous saying (although the concept can be found in traditional sources, see Taz, Orah Hayyim 267:1)[34] However, for one whose only Jewish knowledge comes from the yeshiva, this information would be unknown, and it is easy to see how such a statement (“more than the Jews have kept the Sabbath the Sabbath has kept the Jews”) could “infiltrate” this closed world and become just another ma’amar hazal.[35] It reminds me of how when I was a kid and my friends and I went to Boro Park for Shabbatons we would have been able to hum niggunim which came from popular songs and commercials, and our hosts wouldn’t have known a thing. At the Rutgers Chabad house in the 1980’s they even had a niggun to the tune of the theme song for Bumble Bee tuna. For those too young to remember it, see it here.

Of course, Ahad ha-Am’s statement is sound Jewish doctrine, as should be expected from one who had a hasidic upbringing (he was born in Skvira). I don’t even think that the saying was original to him. Rather, he was repeating a hasidic idea that he heard in his youth. I say this because Rabbi Uri Topolosky – who is currently rebuilding Orthodox life in New Orleans[36] – called my attention to the following passage in the Sefat Emet to parashat Ki Tisa (from 1873; p. 198 in the standard edition):

ואך את שבתותי כו’ פי’ שלא להיות רצון ותשוקה לדבר אחר בעולם, רק להשי”ת שהוא שורש חיות האדם שתתדבק בו בשבת קודש . . . גם מה שמירה שייך לשבת אדרבה שבת שומר אותנו.

NOTES:

[15] “The Silence of Rayna Batya: Torah, Suffering, and Rabbi Barukh Epstein’s ‘Wisdom of Women.'” Torah u-Madda Journal 6 (1996): 127, n. 62.

[16] Torah u-Madda Journal 7 (1997): 197. Since I mention the fine scholar Don Seeman, let me also call attention to his article “Ethnographers, Rabbis, and Jewish Epistemology: The Case of the Ethiopian Jews,” Tradition 25 (1991): 13-29. In this article he deals with the issue I touched on in two earlier posts, namely, does “halakhic truth” need to correspond to what academics regard as “scholarly truth.”

[17] I thank Eliezer Brodt for calling it to my attention (it is not mentioned in Beit Eked Sefarim). Subsequently, I saw that it is mentioned by Yaakov Bazak, “Al Derekh Ketivat ‘Torah Temimah,’” Sinai 66 (1969): 97.

[18] Thus, R. Moshe Meiselman could write: “In the volume of responsa, Maayan Ganim, the author not only permits motivated women to study the Torah but praises them and urges his audience to encourage them in their work.” See Jewish Woman in Jewsh Law (New York, 1978), 38.

[19] R. Menahem Kirschbaum, Tziyun li-Menahem (New York, 1968), 263, points out that contrary to what Epstein states, Tosafot Tom Tov referred to him as a grammarian when Archivolti was quite old.

[20] “Rayna Batya and other Learned Women: A Reevaluation of Rabbi Barukh Halevi Epstein’s Sources,” Tradition 35 (2001): 61.

[21] See here

[22] See Kitvei ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan, part 2, p. 142, where he addresses someone as נכד איש אלקים גדול בעל התניא זי”ע ועל כל ישראל אמן. [23] See ibid., p. 154, for R Yehiel Michel’s 1906 letter of recommendation for R. Zevin. [24] See R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, Beni Vanim, vol. 2, no. 8. In the introduction to Kitvei ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan one finds the following:

על מעמדו של הערוך השולחן כרבן של ישראל ופוסק הדור [שיש הסוברים שהוא הראשון במעלה ואחרון בזמן והלכה כמותו בכל מקום. עי’ בני בנים] אין כאן המקום להרחיב. What kind of reference is this? Most readers won’t even know what Bnei Vanim is. Why is the author, the volume, and page number not given? Why is R. Joseph Elijah Henkin’s name not mentioned? Furthermore, R. Henkin never said that the halakhah is always in accord with the Arukh ha-Shulhan. (Let’s not forget, the Arukh ha-Shulhan thought you could use electricity on Yom Tov.). His comment dealt only with the Arukh ha-Shulhan vs. the Mishneh Berurah.

For Eliezer Brodt’s review of this work, see here.

I have only skimmed part 2 of this important volume, but since it will probably be reprinted, let me make a few corrections and one addition.The transcription of R. Yehiel Michel’s handwriting on the first page is incorrect.

P. 79 s. v. והנה: The word הארוך should be האריך.

P. 146 s.v. גי”ק. The sentence reads: ורבות נצטערתי והמו מעי לו שירדפו גאון מובהק כמו”ב.

The abbreviation should be כמי”ב – כמותו ירבו בישראל. See p. 152, top line.

P. 173 no. 137: R. Aryeh Jacob Katznelson was the son-in-law of R. Yehiel Michel’s brother-in-law.

P. 193 n. 17: The quotation does not appear in no. 39.

According to Glick, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot he-Hadash, vol. 1 (Jerusalem and Ramat Gan, 2007), 582 (no. 2186), material from R. Yehiel Michel appears in R. Moses Spivak, Mateh Moshe (Warsaw, 1935).

[25] Hayyim Schirmann, Ha-Shirah ha-Ivrit bi-Sefarad u-ve-Provence (Jerusalem, 1954), vol. 1, no. 143; translation in Norman Roth, “‘Deal Gently with the Young Man’: Love of Boys in Medieval Hebrew Poetry of Spain,” Speculum 57:1 (1982): 45.

[26] See here.

[27] see my “Obituary: Professor Mordechai Breuer zt”l,” the Seforim blog (Monday, 11 June 2007), available here.

[28] See Yabia Omer, vol. 9, Orah Hayyim no. 108 (p. 269).

[29] See Shmuel Glick, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot he-Hadash, vol. 1 (Jerusalem and Ramat Gan, 2006), 57.

[30] The Pentateuch: Its Composition and Its Authorship (Jerusalem, 1967), 33.

[32] See here.

[33] See Avraham Korman, Ha-Tahor ve-ha-Mutar (Tel Aviv, 2000), 99.

[34] See Al Parashat ha-Derakhim, ch. 51, available here. The actual quote is

[35] R. Herzog was well aware of whose saying he was adapting when, in an article on Taharat ha-Mishpahah published in Ha-Pardes (September 1947, p. 15), he wrote:

[36] See here.

Marc B. Shapiro – Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 3

I thought that I had exhausted all I had to say about Rabbi Zvi Benjamin Auerbach’s edition of the Eshkol — see my first two posts at the Seforim blog, here and here [and elaborations] — but thanks to some helpful comments from readers, there is some more material that should be brought to the public’s attention. Even before looking at this, let me express my gratitude to Dan Rabinowitz who sent me this picture of a youthful Auerbach. In my first post I cited R. Yitzhak Ratsaby as a very rare example of a posek who is aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol. A scholar who wishes to remain anonymous, and who has helped me a great deal in the past,[1] called my attention to R. Yehiel Avraham Zilber (the son of R. Binyamin Yehoshua Zilber), who is also aware of the Eshkol problem. In his Berur Halakhah, Yoreh Deah (second series), p. 111, he notes that R. Ovadiah Yosef cites Auerbach’s Eshkol in matters of hilkhot niddah. Yet the authentic Eshkol does not have any section for niddah. In fact, as Yaakov Sussman has pointed out,[2] Auerbach’s Eshkol, vol. 1, p. 117, also refers to the Yerushalmi on Niddah. However, this is impossible as neither R. Abraham ben Isaac nor any of the other rishonim had this volume.

In my first post I cited R. Yitzhak Ratsaby as a very rare example of a posek who is aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol. A scholar who wishes to remain anonymous, and who has helped me a great deal in the past,[1] called my attention to R. Yehiel Avraham Zilber (the son of R. Binyamin Yehoshua Zilber), who is also aware of the Eshkol problem. In his Berur Halakhah, Yoreh Deah (second series), p. 111, he notes that R. Ovadiah Yosef cites Auerbach’s Eshkol in matters of hilkhot niddah. Yet the authentic Eshkol does not have any section for niddah. In fact, as Yaakov Sussman has pointed out,[2] Auerbach’s Eshkol, vol. 1, p. 117, also refers to the Yerushalmi on Niddah. However, this is impossible as neither R. Abraham ben Isaac nor any of the other rishonim had this volume.

Zilber writes that his own approach is not to rely on anything in either Auerbach’s Eshkol or the Nahal Eshkol. In his Berur Halakhah, Orah Hayyim (third series), p. 16, he also states that a certain passage in Auerbach’s Eshkol, Hilkhot Tzitzit cannot be authentic. Before I was alerted to these two sources I had never examined any of Zilber’s volumes (although I have perused the works of his father). Now that I have looked at them I see that they contain a great deal of learning, but my sense is that they are of no significance in the halakhic world, and are rarely quoted.

This doesn’t mean that they are not valuable in and of themselves, but with so many halakhic books being published, only some can make it to the top. The rest, no matter how learned, remain little studied and even less quoted. One must feel bad for authors who put so much effort into producing their works which could be of great use to people, yet at the end of the day do not have any impact.

As Eliezer Brodt has already pointed out, in a previous post at the Seforim blog, with respect to books on hilkhot shemitah, although new volumes continue to appear, it is hard to believe that much of anything original is being added.[3] The same can be said for the laws of Shabbat, where I don’t see how another new book recording the halakhot can possibly have any value as we already have so many fine books in this area. If the author is going to come up with new rulings, then fine, but it is hard to see how the world will benefit from yet another collection of the various melakhot and what is permitted and forbidden.

This doesn’t mean that up-and-coming halakhic scholars have nothing to write about. For example, there is only one book on the halakhic issues involved in sex change operations, so here is an area that cries out for our best and brightest to direct their talents towards. For those who are writing books that are not given the attention due them, one should not lose hope. Occasionally a book that is ignored in its time comes back in a future generation and assumes great popularity (e.g., the Minhat Hinnukh), while books which were very popular in previous years fall out of style. One example of the latter is the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh. When I was young everyone seemed to study it. It has been reprinted numerous times and also translated into many languages. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, it went through fourteen editions in the author’s lifetime, which I think is a record for halakhic works. Yet today, I don’t know anyone who uses it as a work of practical halakhah. (Simply writing this ensures that people will e-mail me to point out that there are indeed some who still use it).

For those who are writing books that are not given the attention due them, one should not lose hope. Occasionally a book that is ignored in its time comes back in a future generation and assumes great popularity (e.g., the Minhat Hinnukh), while books which were very popular in previous years fall out of style. One example of the latter is the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh. When I was young everyone seemed to study it. It has been reprinted numerous times and also translated into many languages. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, it went through fourteen editions in the author’s lifetime, which I think is a record for halakhic works. Yet today, I don’t know anyone who uses it as a work of practical halakhah. (Simply writing this ensures that people will e-mail me to point out that there are indeed some who still use it).

Returning to the anonymous scholar mentioned above, he also alerted me to a letter by R. Michael[4] Aryeh Stiegel which appeared in Tzefunot 1 (Tevet, 5749): 108. In this case I had actually seen the letter, as I own the journal and even have my pen mark on this page. But I had forgotten about it, so once again I am in the anonymous scholar’s debt. Before noting what he says, let me repeat what I mentioned in a previous post, namely, that the publication of the fourth volume of the Eshkol is very strange. We are given no information about the manuscript such as where it came from and why no one, including Auerbach’s family, had ever heard of it until it was published.

There is one other point which I neglected to make in my previous post, but it also is relevant. In 1974 Bernard Bergman published an essay on Auerbach in the Joshua Finkel Festschrift (later included as an appendix to vol. 4 of the Eshkol) in which he defended him against Albeck’s attack. At the time of this essay Bergman knew nothing about any unpublished manuscript of Auerbach’s Eshkol. It is very suspicious, to say the least, that Bergman is also the one to publish the newly discovered volume. Are we supposed to assume that it is just coincidence that Bergman, who earlier had published an essay on Auerbach, discovered this manuscript? (Those who are old enough will recall that during these years Bergman had lots of other things on his mind.) Of course, it is possible that some rare book dealer came into possession of the manuscript and knowing Bergman’s interest in Auerbach, sold it to him. In my previous post I stated that despite the problems that can be raised about the new volume, barring any further evidence we should give Bergman the benefit of the doubt.

Yet Stiegel notes something which should force us to reopen the issue. In volume 4, p. 26 n. 24, we find the following in the Nahal Eshkol.

The problem is that the edition of Ra’avan with R. Solomon Zalman Ehrenreich’s commentary Even Shlomo only appeared in 1926, many years after Auerbach’s death. This sort of anachronism is often what enables scholars to uncover a fraud.

When problems became apparent in Auerbach’s edition, Albeck called for the manuscript to be produced, and this was never done. Here too, I call for the manuscript of volume 4 to be produced, and for the publisher, Machon Harry Fischel, to join in this demand. Only when we can examine the manuscript will we be able to determine what is going on. If the answer given is that the manuscript cannot be located, which was the same answer given one hundred years ago, then the possibility that Eshkol volume 4 is a late twentieth century forgery will have to be seriously considered.

The anonymous scholar also alerted me to R. Hayyim Krauss’ Toharat ha-Shabbat ke-Hilkhatah. Krauss is known for a campaign he mounted in the 1970’s, culminating in the publication of his books Birkhot ha-Hayyim and Mekhalkel Hayim be-Hesed, which were in large part devoted to showing that the proper – and original — pronunciation in the Amidah is morid ha-geshem, not gashem. There is no doubt that Kraus was correct, but I don’t know if his campaign bore any fruit. Certainly in the United States when I was growing up, virtually everyone said gashem since that is what the siddurim had, including Brinbaum. Matters have changed greatly in the last twenty years because of the ArtScroll siddur. This siddur vocalizes – or, to use the word that ArtScroll prefers, “vowelizes” – גשם as geshem. I have previously noted one example where the Artscroll siddur has changed the davening practices of the American Orthodox community[5] and this is another. Had the ArtScroll siddur given gashem as the pronunciation, that’s what we all would be saying now.

Since this blog is devoted to seforim, with a great focus on bibliographical curiosities, let me mention the following: It has been awhile since I’ve seen the literature about geshem vs. gashem, but I remember that the side that supported gashem was able to show that it was not only grammarians who supported this reading, but R. David Lida (c. 1650-1696) Ashkenazi rav of Amsterdam, also attested to it. In fact, he might be the earliest authority to do so. But those who cited Lida didn’t know a couple of things about him. Neither do the people who keep publishing his works. To begin with, Lida was a plagiarizer, and not a very skilled one at that.[6]

People can live with plagiarism, especially as it is not uncommon in haredi “mehkar.”[7] But worse, much worse, is that Lida also appears to have been a Sabbatian. In my Limits of Orthodox Theology, p. 42 n. 21, I called attention to something similar. The Yemenite kabbalists who attacked R. Yihye Kafih made use of, and defended, a Sabbatian work written by Nehemiah Hayon. It was only after R. Kook pointed out the true nature of Hayon’s work that they excised this defense. As I commented in my book, this shows the elasticity of apologetics, in that if one beleves a work is “kosher,” he will devote great efforts to defending it, but after learning that the author is a Sabbatian the defense is immediately dropped. We must ask, however, why were the ideas in this work acceptable before the author’s biography was known?

Returning to Krauss’ Toharat ha-Shabbat ke-Hilkhatah, in volume 1 of this work he cites Auerbach’s Eshkol. In volume 2, p. 450, Krauss publishes a letter he received from R. David Zvi Hillman. Hillman, in addition to being an outstanding talmid hakham, also has a real historical sense and many years ago edited Iggerot ha-Tanya u-Venei Doro (Jerusalem, 1953). In more recent years he published an interesting, though wrong-headed, article arguing that Meiri’s views of anti-Gentile halakhot are not to be taken seriously but were written due to fear of the censor (which was a concern even in pre-printing days).[8] He has also been involved with the Frankel edition of the Rambam, most recently editing Sefer ha-Mitzvot. Despite its problems, the Frankel edition of the Mishneh Torah is now the standard edition for both yeshivot and the academic world.[9]

As everyone knows, the Frankel edition has been attacked for systematically ignoring the writings of some prominent non-haredi gedolim. For example, there are no references to R. Kook, even though he wrote a commentary on the Rambam’s shemitah laws, which will be mentioned in an upcoming post at the Seforim blog. (He is cited the ArtScroll Mishnah volume on Shevi’it.) It was because of this affront that R. Kook’s followers have put out a separate index of commentaries on the Mishneh Torah, which is now available online. See here.

A particularly harsh criticism of the Frankel edition, which appeared as an “open letter,” is found here:

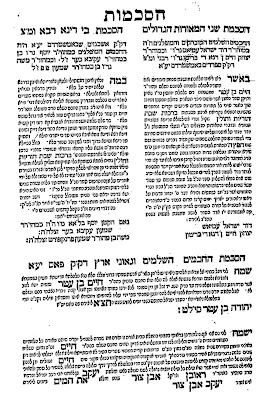

Hillman chose to answer this critique. He briefly mentions the issue of R. Kook, but has a lot to say about R. Kafih, and his critique of the latter is incredibly sharp. Here is his letter:

Hillman chose to answer this critique. He briefly mentions the issue of R. Kook, but has a lot to say about R. Kafih, and his critique of the latter is incredibly sharp. Here is his letter:

Even if one doesn’t agree with him, it should be obvious to all that Hillman has a much broader knowledge than the typical talmid hakham. It therefore should not be surprising that he was critical of Krauss for including Auerbach’s Eshkol. In fact, Krauss does not even print Hillman’s entire letter, but cuts out a section that no doubt would have been seen as disrespectful to Auerbach. Thus, Hillman writes:

Even if one doesn’t agree with him, it should be obvious to all that Hillman has a much broader knowledge than the typical talmid hakham. It therefore should not be surprising that he was critical of Krauss for including Auerbach’s Eshkol. In fact, Krauss does not even print Hillman’s entire letter, but cuts out a section that no doubt would have been seen as disrespectful to Auerbach. Thus, Hillman writes:

The second ellipsis was inserted by Krauss. In his letter Hillman must have written, “Even if you want to say that Auerbach didn’t forge this section, and it really was stated by the Eshkol.” Yet Krauss didn’t want anything negative about Auerbach to appear in print, so he cut it out. Hillman also calls attention to the comments of R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira in the introduction to his Darkhei Teshuvah on hilkhot mikvaot. Here Shapira notes that the Maharsham cited Auerbach’s Eshkol, and this once again raises the problem I have earlier discussed, namely, what to do with pesakim that rely on forged texts? (This is not such a problem in hilkhot mikvaot, as Shapira notes that most of what is quoted from Auerbach’s Eshkol is le-humra).

Shapira states that he is not prepared to decide the matter of the authenticity of Auerbach’s Eshkol, yet according to Hillman נראה מכתלי דבריו שדעתו נוטה לצד המערערים על אמיתותו. It is obvious that the reason Shapira does not definitively decide the matter is because of his feeling of respect for Auerbach as a great talmid hakham. The notion that such an outstanding Torah scholar, one of the German rabbinic elite, could perpetrate such a fraud is difficult for people to accept. Yet Shapira is also surprised that the Maharsham cites Auerbach’s Eshkol entirely oblivious to the problems with this edition.

I don’t see this as unusual at all. Shapira was an incredibly learned man, with knowledge of all sorts of things, but the Maharsham was an ish halakah whose life was spent in Shas and Poskim. Similarly, although R. Moshe Feinstein quotes Auerbach’s Eshkol, I would assume that he too had never heard of the controversy, as it is not something that penetrated the walls of the traditional Lithuanian Beit Midrash (at least not until so many bachurim began reading the Seforim blog!). Shapira writes:

In his reply to Hillman, Krauss states that he was indeed aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol, and even referred to Shapira’s introduction, but he did not want to elaborate (and indeed, he never quotes what Shapira says, but only tells the reader to examine it). I think that many people in the traditional world who know about the issue have this problem as well. They are between a rock and a hard place. If they say nothing, then a forgery is allowed to remain part of the Torah world. Yet if they write against it, they must take on someone who in his lifetime was recognized as one of the gedolim of Germany. Like all gedolim, he was also regarded as a great tzaddik.

Krauss does allow himself to say the following:

Prof. Yaakov Spiegel has also called my attention to his article in the latest Sidra[10] focusing on the various terms used for describing the blessing of the new moon. It so happens that in medieval times the term kiddush levanah was not found in either the Sephardic world or among Provencal scholars. Yet as Spiegel notes, this expression is found in Auerbach’s Eshkol, in a section that is missing from Albeck’s edition. This is another proof (if any was needed) that Auerbach’s edition is a forgery.[11]

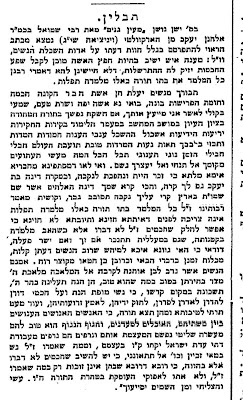

The Auerbach forgery relates to another issue, that of rabbis lying and making things up for what they view as good reasons (which ties into my current project on censorship). Let me offer one example of this, but first I must give some background. If there is one thing Orthodox Jews know it is that sturgeon is a non-kosher fish. Yet as with so much else that people know, this is not exactly correct. While our practice today is not to eat sturgeon, no less a figure than the great R. Yehezkel Landau, the Noda bi-Yehudah, permitted it.[12] This decision led to enormous controversy as many of the greatest rabbis of Europe lined up in opposition.

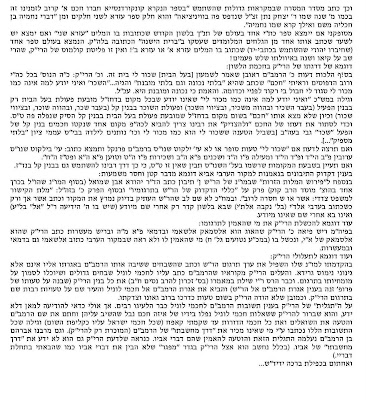

Rabbi Aaron Chorin, at this time rav of Arad, Hungary, was a student of R. Yehezkel and he took up the cause of kosher sturgeon, publishing the volume Imrei Noam (Prague 1798) in support of his teacher’s view. At this time he had not yet crossed over to the dark side where he would, in the Hatam Sofer’s words, become known as אחר, an abbreviation of the way Chorin signed his name: Aron Choriner Rabbiner (see Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, 6:96). R. Isaac Grishaber, the rav of Paks, took up the battle against Chorin and published the volume Makel Noam (Vienna 1799). Here is the title page of the book: Chorin responded with another book on the subject, Shiryon Kaskasim (Prague, 1800).

Chorin responded with another book on the subject, Shiryon Kaskasim (Prague, 1800).

Grishaber was a fairly well known rabbi, and in recent years Torah journals have begun to print his unpublished writings. The problem that Grishaber was up against was that even with the many rabbis who wrote haskamot for his book, the great R. Yehezkel Landau had ruled differently. How could he destroy Chorin’s argument, convince the people that he was right, and most importantly, spare Jews from eating non-kosher when the recently deceased gadol ha-dor stood in his way?

Even before Chorin published his book, Grishaber had been on a crusade to have sturgeon declared as non-kosher. As part of this battle Grishaber took a fateful step which I have no doubt was done le-shem shamayim, but which from our perspective must be regarded as reprehensible.

In his effort to stop the eating of sturgeon, which he firmly believed was a terrible sin, Grishaber declared that R. Yehezkel sent him a letter retracting his decision and asking him to forward this letter to the rabbi of Temesvar, to whom he originally gave his lenient opinion. Grishaber states that the original letter of R. Yehezkel, which he received and sent on to the other rabbi, was lost in the mail.[13] He also writes that he misplaced the copy he made of R. Yehezkel’s original letter to him. This is all very fishy. Not surprisingly, R. Yehezkel’s son, R. Samuel, and R. Yehezkel’s leading student, R. Eleazar Fleckeles, rejected Grishaber’s testimony. They declared that he never received such a letter. In other words, he was lying when he stated that the Noda bi-Yehudah had retracted his opinion.

These are strong words, but it is hard to read what R. Samuel and R. Fleckeles write and still have any doubts that Grishaber was engaging in a fraud – although as R. Samuel states, Grishaber no doubt believed that in the effort to stop people from eating non-kosher even this was permissible. Here are some of R. Samuel’s words (Noda bi-Yehudah, Yoreh Deah, tinyana, no. 29), which are very interesting in that he keeps the standard respectful phrases at the same time that he is telling Grishaber that he is a liar.

Grishaber also had to deal with the fact that in Turkey the Jews ate sturgeon. To this he replied that one could not rely on the Turkish Jews since many of them were still followers of Shabbetai Zvi. R. Samuel had no patience for this nonsensical assertion.

Fleckeles also speaks harshly (Teshuvah me-Ahavah, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 329), and this comes after beginning his letter with all the customary rabbinic introductory words of praise.

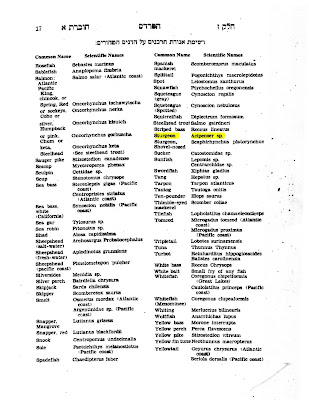

Although there were some who supported R. Yehezkel, this remained a minority opinion. By now no one is in dispute about this matter. Yet I wonder if any readers recall eating sturgeon in the United States. I ask because there was a time when sturgeon was regarded as kosher in this country. Here is a page from the list of kosher fish published by Agudas ha-Rabbonim in Ha-Pardes, April 1933. This advertisement for delicious sturgeon appeared in subsequent issues of Ha-Pardes.

This advertisement for delicious sturgeon appeared in subsequent issues of Ha-Pardes.

1. The Chief Rabbinate of Israel declared swordfish to be kosher, and in a 1960 responsum R. Isser Yehudah Unterman defended this ruling. In response to R. Moshe Tendler’s objection, Unterman reaffirmed its kosher status.[14] It is likely that the widespread assumption that swordfish is not kosher can be traced to Tendler’s successful efforts in this regard. Today, who even remembers the that swordfish used to be kosher?

2. There was a great rav in Boston named Mordechai Savitsky. To a certain extent he was an adversary of the Rav and was one those tragic figures in American Orthodoxy. His Torah knowledge was the equal of any of the outstanding Roshei Yeshiva who became so popular, but he was never able to find his place. He publicly declared – and in his Shabbat ha-Gadol derashah no less – that swordfish is kosher.

These two points are enough to show that the issue of swordfish is anything but settled, and is certainly not an Orthodox-Conservative issue. Zivotofsky’s article will be quite illuminating in this regard.

Notes:

[1] See The Limits of Orthodox Theology, Preface.

[2] Mehkerei Talmud 2 (1993), 255 n. 196.

[3]”R. Yaakov Lipshitz and Heter Mechirah,” the Seforim blog (October 11, 2007), available here.

[4] In an effort to keep far away from non-Jewish names, many people who are named מיכאל spell it as Michoel. I have even seen Mecheol. Certainly, no one today in the haredi world who has the name משה would write his English name as Moses, as is found on R. Moshe Feinstein’s stationery.

[5] See here at note 8.

[6] See Bazalel Naor, Post-Sabbatian Sabbatianism: Study of an Underground Messianic Movement (Spring Valley, 1999), 38; Marvin Heller, “David ben Aryeh Leib of Lida and his Migdal David: Accusations of Plagiarism in Eighteenth Century Amsterdam,” Shofar 19 (Winter 2001): 117-128.

[7] Yet can they live with a well-known contemporary rabbi who not only falsified a book he worked on, but has ignored a series of summons to a beit din? See here (and here) for more. Since the censorship and forgery he engaged in are directed against Chabad, it is possible that in his mind he has done no wrong. He probably also assumes that a Chabad beit din is not valid, and therefore he can ignore it.

[8] “Leshonot ha-Meiri she-Nikhtevu li-Teshuvat ha-Minim,” Tzefunot 1 (5749): 65-72.

[9] In my forthcoming book, Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters (University of Scranton, 2008), I give examples of some of the problems. The book should appear in another few months.

[10] “Le-Mashmaut ha-Bituyim: Kiddush Hodesh, Birkat Levanah, Kiddush Levanah,” Sidra 22 (2007): 185-200.

[11] For other forgeries in Auerbach’s Eshkol, see Louis Ginzberg, Perushim ve-Hiddushim Birushalmi, vol. 1, Introduction, p. 84, and vol. 4, p. 6. I owe these references to the anonymous scholar.

[12] Noda bi-Yehudah, Yoreh Deah, tinyana, no. 28.

[13] See Yisrael Natan Heschel, “Mismakhim Nosafim le-Folmos Dag ha-Stirel bi-Shenat 5558,” Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael (Sivan-Tamuz 5755): 109.

[14] See Shevet mi-Yehudah, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 5.

Marc B. Shapiro – Responses to Comments and Elaborations on Previous Posts

Marc B. Shapiro holds the Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Scranton. He is a frequent contributor to the Seforim blog and his most recent posts are “Forgery and the Halakhic Process” and “Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 2.”

The post below was written as part of “Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 2,” which the baale ha-blog have split up for the convenience of the readers of the Seforim blog. As such, the footnotes continue from the conclusion of the previous post.

by Marc B. Shapiro

1. Some were not completely happy with an example I gave of an error in the Chavel edition of Ramban in a previous post at the Seforim blog. So let me offer another, also from one of Ramban’s talmudic works (since that was the genre I used last time). In Kitvei Ramban, 1:413, Chavel prints the introduction to Milhamot ha-Shem. The Ramban writes:

In his note, Chavel explains the last words as follows:

Yet what Ramban means by למתחיל פרק אין עומדין are the children who begin their talmudic study with Tractate Berakhot. In other words, it is only the explanations and pesakim of the Rif that are obvious even to the beginner that have not been challenged.[21]

Regarding the example I gave in my last post at the Seforim blog, I forwarded to R. Mazuz one of the questions I received, which dealt with the form of the verb אסף found in the Ramban:

He answered as follows:

I must note, however, that while R. Mazuz’ understanding of Ps. 105:25 is in line with the Targum, this is not how the standard Jewish translations understand the verse.

(Shortly before writing this, I read about the outrage taking place in Emanuel, where in the local Beit Yaakov Sephardi students are being segregated from Ashkenazim to the extent that the two are not even permitted to play together. The Shas party has referred to this as nothing less than Apartheid, which it surely is.[22] What’s next? Mehadrin buses where the Sephardim sit in the back? Of course, when this happens the justification given will once again be that Ashkenazim are on a higher spiritual level and that’s why they can’t sit with Sephardim, not that they are racist, chas ve-shalom.

I mention this because R. Mazuz has made a comment that is relevant in this regard. Speaking to Ashkenazim who like to imagine the tannaim as “white”, he has called attention to Negaim 2:1, where R. Yishmael states that Jews are neither black nor white, but in between. In other words, the tannaim looked like Sephardim.)

2. One of the e-mails to me stated that we Modern Orthodox types love to criticize Artscroll, but how come we never point out errors in the Rav’s works. I can’t speak for anyone else, and it is true that the Rav has now assumed hagiographic standing, meaning that it has become much harder to criticize him or point out supposed errors in his works. However, if I detect what I think is an error I will definitely call attention to it, and I believe the Rav would expect as much, for this is a sign that you are taking his writing seriously. If the Rambam could make careless errors (the focus of a large section of my forthcoming Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters, available for pre-order on Amazon for only $8) then anyone can err, and it is no disrespect to call attention to these errors. There are actually a number of seforim which have sections in which they call attention to careless errors or things overlooked in the writings of various aharonim.

I understand why students of the Rav and his modern day hasidim might be reluctant to do so, but I never had any real relationship with him and can approach matters as an outsider. My only connection to the Rav was one summer in the Boston kollel (1985, the last year of the kollel. When I lived in Brookline in the 1990’s the Rav was no longer well). I was, however, privileged, together with Rabbi Chaim Jachter, to drive him back and forth to the Twersky’s house, and was thus able to hear some memorable things from him which I will record in a future post at the Seforim blog.

While on the topic of the Rav, let me also state that I used the Rav’s Machzor on Yom Kippur. I found the commentary uplifting and great credit must go to Dr. Arnold Lustiger for the effort he put into the volume. But there is one thing in the Machzor that annoyed me. It relates to what is called Hanhagot ha-Rav. This section includes all of the various practices of the Rav. This is certainly worth knowing and it wouldn’t have bothered me had it simply appeared at the beginning of the Machzor. But that is not the case.

Before I explain the problem, let me start with the following: A number of years ago I asked Prof. Haym Soloveitchik what the practice of his father was in a certain matter. His response was short and crisp. He told me that he never answers questions about his father’s hanhagot, and that to do so would be in total opposition to his father’s outlook.

I assume that today, if it was clear that my concern was of an academic nature, he would be more forthcoming. But back then I was another unknown kid writing to him trying to find some interesting practice of the Rav.

The way I understood Prof. Soloveitchik is that his father, like many gedolim, had practices that diverged from the mainstream. They came to these practices based on their original reading of the sources. Yet these were entirely private practices, reserved at most for other family members and perhaps some very close students. Because they went against the mainstream, they were not for mass consumption. Along these lines, R. Zevin reports, in his article on R. Hayyim Soloveitchik in his Ishim ve-Shitot, that it was such an outlook that explained why R. Hayyim did not want to decide practical halakhah. His original mind would lead him to overturn many accepted halakhot, yet he was not prepared to do so.

Returning to my problem with the Rav’s Machzor, we are told the following in this book: The Rav reversed the order of the final two phrases in the benediction ולירושלים in the Amidah, saying וכסא דוד מהרה לתוכה תכין prior to saying ובנה אותה בקרוב בימינו בנין עולם. This is the way the Sephardic siddurim have it, but certainly the Rav did not expect the entire Ashkenazic world to abandon their long-standing practice because of his practice. Yet when this paragraph (in minhah before Yom Kippur and maariv following Yom Kippur) appears there is a note telling people how the Rav read it. This is certainly encouraging people to abandon the Ashkenazic tradition in favor of the Rav’s reading. From all that I know about the Rav, this is not something he would have wanted.

Another example is that we are told that the Rav omitted the blessing הנותן ליעף כח as it is post-Talmudic. What possible purpose can such information have when provided on the page where this blessing appears, other than to lead people to omit the blessing? Is one to assume that the Rav really wanted people to reject the universal Ashkenazic practice? The Rav never got up at an RCA convention and told people that this is what they should do. Even at the Maimonides minyan and school there is no official minhag to omit this blessing. R. David Shapiro reported to me that almost all those who daven from the amud at the Maimonides synagogue minyan recite the blessing, and everyone does so at the Maimonides school minyan. Yet I wonder how many followers of the Rav are now omitting the blessing after seeing what appears in the Rav’s Machzor.

There are other examples, and as I said above, I don’t believe that this information should be secret. However, when you put it on the relevant pages of the Machzor, where the instructions to the worshipper are designed to be for practical application, you are telling people that if they see themselves as followers of the Rav, then they should follow his practices.

Since my correspondent made the false assumption that I would never point out an error of the Rav, and indeed almost challenged me, let me offer one. In Halakhic Man, page 30, in writing about halakhic man’s relationship with transcendence, the Rav writes:

It is this world which constitutes the stage for the Halakhah, the setting for halakhic man’s life. It is here that the Halakhah can be implemented to a greater or lesser degree. It is here that it can pass from potentiality into actuality. It is here, in this world, that halakhic man acquires eternal life! “Better is one hour of Torah and mitzvot in this world than the whole life of the world to come,” stated the tanna in Avot [4:17], and his declaration is the watchword of the halakhist.