David Berger A Brief Response To Marc B. Shapiro

This is his first contribution to the Tradition Seforim blog.

Since I've written an entire book about Chabad messianism, there is little point in my rehearsing the arguments here in truncated form. I will make just two brief observations.

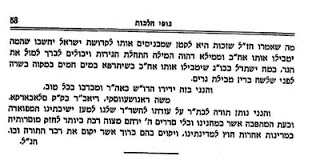

First, Prof. Shapiro writes, "Unlike Professor David Berger, it doesn't overly concern me that the belief in a Second Coming didn't exist twenty years ago. After all, Judaism is a developing religion." My point, of course, is not that the belief did not exist twenty years ago. It is that Jews through the ages repeatedly–through both word and deed–rejected the possibility that God would send the Messiah to announce that redemption was imminent, preside over a movement identifying him as the Messiah, and then die in an unredeemed world. In short, Chabad messianism destroys the gedarim, or defining parameters, of one of the ikkarei he-emunah. Since this point was a key argument used against Christianity for untold generations, rendering it false is a betrayal not only of the Jewish faith but of generations of Jewish martyrs.

Second, there is the reality of toleration by rabbinic leaders (my "scandal of indifference"), which for Prof. Shapiro determines not only what Judaism has become but what we ought to accept as legitimate. Now, in discussing Christianity, he goes on to say that the incarnation, or belief that a human being is God, is way over the line. He does not, however, return to Chabad in that part of his discussion, because he would be required to confront his earlier criterion with all its terrible consequences. I have shown that a significant segment of Chabad hasidim (not just a few lunatics) maintain a fully incarnationist doctrine, and yet the rabbis who believe this (including some of Prof Shapiro's "great Torah scholars" who allegedly deserve respect despite their adherence to the "messianic foolishness") are also generally treated as Orthodox rabbis in every respect. The reasons for this indifference are discussed in chapter 13 of my book, and they have little to do with theology. It may indeed be that even this belief will become so legitimated that Judaism will be fundamentally transformed; it is, however, much too early to make such a judgment even about "mere" messianism, and it is beyond irresponsible to look at this development with the cool eye of an analyst without attempting to stem the tide. Historic Judaism is in mortal danger. Let outsiders watch this process in detached fascination. Those of us who care about preserving the faith of our ancestors must take a stand. If we fail, the proper reaction will not be to accept this with equanimity as analogous to the distribution of shirayim; it will be to tear keriah as we mourn the destruction of core elements of our faith.

Marc B. Shapiro: Thoughts on Confrontation & Sundry Matters Part I

What follows is a continuation of this post.Some people are so set on showing the differences between Christianity and Judaism that in the process they end up distorting Judaism. Let me start with an example that for the last fifteen years must be considered a Jewish teaching. By Jewish teaching I mean a view that is taught in the observant community. This doesn’t mean that all or even most people will agree with it, anymore than they agree with the ideas of Daas Torah, religious Zionism, religious anti-Zionism, or that the shirayim of the Rebbe has mystical significance. But agree or not, these are clearly Jewish teachings. Today it must be admitted that Judaism and Christianity share a belief in the Second Coming of the Messiah. While this is an obligatory belief for Christians, for Jews it is, like so many other notions, simply an option. The truth of my statement is seen in the fact that messianist Habad is part and parcel of traditional Judaism, and, scandal or not, most of the leading Torah authorities have been indifferent to this. That is, they see it as a mistaken belief, but not one that pushes its adherent out of the fold. In other words, it is like so many other false ideas in Judaism, all of which fall under the rubric “Jewish beliefs.” As long as these beliefs don’t cross any red lines, the adherents are regarded as part of the traditional Jewish community. To give a parallel example, many people reading this post are good rationalists, and therefore regard astrology as quite foolish. But we are all well aware of the many Jewish teachers who taught the efficacy of this system. Therefore, astrology must be regarded as an acceptable belief for adherents of traditional Judaism. Whether it is correct or not is a completely different matter, and if the latter criteria determines whether something is included under the rubric of traditional Judaism, then it will be a small tent indeed. Unlike Professor David Berger, it doesn’t overly concern me that the belief in a Second Coming didn’t exist twenty years ago. After all, Judaism is a developing religion. Two hundred years ago leading Torah scholars criticized Hasidism for advocating all sorts of new ideas, and yet these too became part of Judaism. In another fifty years the notion of a Jewish Second Coming will probably be seen by most as just another Hasidic eccentricity (albeit the province of only one sect), up there with prayers after the proper time and shirayim. The important point for me is what makes a belief an acceptable one in Judaism is not whether it is new, and certainly not whether it is correct, but whether the rabbinic leaders tolerate it. Over time they have shown that they can tolerate all sorts of foolish doctrines, Habad messianism being merely the latest. Professor Berger argued his case valiantly, but it has largely fallen on deaf ears, and this includes the ears of great Torah scholars. So, like it or not, traditional Judaism now encompasses hasidim and mitnagdim, rationalists and kabbalists, Zionists and anti-Zionists, and those who think the Messiah will be coming for the first time together with those who think it will be a return trip. What has occurred with Habad messianism and its painless integration into wider Orthodoxy can also teach us something with regard to the history of Judaism and Christianity. Had Paul not insisted on his antinomian path, that is, had the Law remained central to early Christianity, there is no reason to assume that there would have been a break with Pharisaic Judaism. When thinking about Habad, there is one other point we have to bear in mind. There are great Torah scholars who unfortunately believe the messianic foolishness, and they should be treated with respect. After all, R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, the Hida, quoted from the works of scholars who continued to believe in Shabbetai Zvi even after his apostasy.[33] He certainly opposed their Sabbatianism, and we must oppose the Habad messianism, but one’s religious legitimacy in contemporary Orthodoxy is not destroyed because of the belief in a false Messiah. Let me now return to an issue mentioned already, namely, the naivete in dealing with the differences between Judaism and Christianity that is common in Orthodox circles, especially among those who engage in apologetics and kiruv type activities. To give an example that I have both seen in print and heard in lectures, there are those who talk about how compared to Catholicism Judaism is a much more realistic religion when it comes to divorce, in that it permits it if people don’t get along. That is fine, as far as it goes, but some people then go overboard and denigrate any outlook that opposes “Judaism’s position.” In doing so, these well-meaning people end up of denigrating Beit Shammai’s view. Some will recall that Beit Shammai said that “a man may not divorce his wife unless he has found in her some unseemly conduct” (Gittin 9:10), which means unchastity. Now the halakhah is not in accord with Beit Shammai, but his is certainly a Jewish position. Any presentation of Judaism that presents the standard view of divorce as “the” Jewish position, and denigrates any other approach, has the unintended consequence of denigrating Beit Shammai as not having had a “Jewish” position. In other words, it is disparaging to Beit Shammai for any contemporary to speak about how Beit Hillel’s view is “better” than that of Beit Shammai. In fact, there are traditional sources that speak about how in Messianic days the halakhah will follow Beit Shammai, in this and in all other disputes. I think the traditional position would be to assert that Beit Hillel’s position is not objectively any “better”, and certainly not more ethical, than that of Beit Shammai. Furthermore, a number of poskim actually hold that Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai only dispute about a second (or subsequent) marriage, but that with regard to the first marriage, Beit Hillel agrees with Beit Shammai that a man can divorce his wife only if he finds a matter of unchastity. R. Solomon ben Simeon Duran goes even further and asserts that in this dispute the halakhah is actually in accord with Beit Shammai! [34] ואע”ג דב”ש וב”ה הלכה כב”ה משמע הכא דהלכה כב”ש This is not the accepted halakhah, but it illustrates how unseemly it is to portray a position held by important poskim as out of touch or foolish. As mentioned above, I have seen many times when apologists try to show the beauty of Judaism by contrasting it positively with some “non-Jewish” position (on the unsophisticated assumption that the best way to better their position is by denigrating another). As noted, I have also observed that sometimes the position they are denigrating happens to also be a Jewish position (just not the accepted position). Of course, when you point this out to them, and show them that the way they were arguing had the unintended consequence of ridiculing a position held by traditional Jewish figures, they immediately apologize and give assurances that they won’t do so again. My question always is, why not? Five minutes ago they were happy to declare how unfair or foolish a certain position is, and once being informed that the position is also held by Jewish thinkers they drop their argument like a hot potato. Are we to conclude that it is not the inherent logic of an argument that gives it validity, but only who its adherents are? Does an approach only stop being ridiculous when the polemicist learns that it was held by a traditional thinker? Obviously yes, which leads to the conclusion that there is no purpose in the polemicist arguing the merits of his case at all, since everything he states is only conditional. In other words, the polemicist is telling us: “I can attack a position as being foolish and illogical, but this is only when I think the position is held by non-Jewish or non-traditional thinkers. Once I learn that the position is also held by traditional thinkers, all of my previous words of criticism should be regarded as null and void.” This is another example of what elsewhere I have termed the “elastic” nature of Jewish apologetics and polemics. With this in mind, let me now say something that I know will make many people uncomfortable, but which I have felt for a long time. Throughout Jewish literature one can find any number of explanations as to how the notion of the Trinity is in direct opposition to Jewish teachings, since Judaism demands a simple, unified God. There is no doubt that for much of our history this was the standard view. However, once the doctrine of the sefirot arises on the scene, matters change. Many of the arguments put forth by kabbalists to explain why the belief in the sefirot does not detract from God’s essential unity could also be used to justify the Trinity, a fact recognized by the opponents of the sefirotic doctrine. Since the doctrine of the sefirot has become part and parcel of Judaism, we must now acknowledge that Judaism does not require a simple Maimonidean-like, divine unity. In fact, without any reference to the sefirot, R. Judah Aryeh Modena was able to conclude that one could indeed justify the notion of the Trinity so that it did not stand in opposition to basic Jewish beliefs about God’s unity. As Modena points out in his anti-Christian polemic, Magen va-Herev, the real Jewish objection to the Christian godhead is not found in any notion of a Triune God, but in the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation.[35] The idea that God assumed human form, i.e., that a human is also God, is regarded by us as way over the line. This is not only because it deifies a human, but also because there is a great difference between a spiritual God divided into different “parts,” and an actual physical division in God. The latter is certainly in violation of God’s unity even according to the most extreme sefirotic formulations. (It would not, however, appear to be in violation of R. Moses Taku’s understanding of God, since he posits that God can assume form in this world at the same time that He is in the heavens. For Taku, Christianity’s heresy would thus be seen only in their worship of a human, which is avodah zarah.) From the Trinity, let’s turn to Virgin Birth, another phenomenon which everyone knows is not a Jewish concept, or is it? If by Virgin Birth one means conception through the agency of God, then there is no such concept in Judaism. Yet if by Virgin Birth we also include conception without the presence of human sperm, then as we shall soon see, this indeed accepted by some scholars. (I stress human sperm, so that we can exclude the legend of Ben Sira’s conception, which occurred by means of a bathtub, not to mention all of the responsa dealing with artificial insemination.) Pre-modern man believed in all sorts of strange things, one of which was the concept of the incubus and the succubus, which was found in many cultures. The idea was that male and female demons would have sex with humans while they slept. Among the outstanding Christian figures who believed the notion possible include Augustine and Aquinas.[36] This was an especially good way to explain an unwanted pregnancy: just blame it on the demon. While the classic example of the incubus is when a male demon comes upon a sleeping woman, there were times when this happened while both parties were awake, and we will soon see such a case in Jewish history. Lest one think that this is only a pre-modern superstition, what about all those people who claim to have had sexual relations with aliens who abducted them?[37] As the superstitions in Jewish society have often mirrored those of the dominant culture, we shouldn’t be surprised that sex with demons comes up in our literature. Already the Talmud (Eruvin 18b) speaks of Adam begetting various types of demons. This source doesn’t say who the mother was, but since it wasn’t Eve it must be a female demon. Yet the Talmud is quick to note that Adam never actually had sex with this female demon. Rather, she impregnated herself with his sperm that was emitted accidentally. Throughout Jewish history there were women who were believed to have had sex with demons, and this raised halakhic issues that had to be dealt with. There is no need for me to give various sources on this as they have been nicely collected by Hannah G. Sprecher in a fascinating article.[38] I will just mention one point which I find interesting, and which I mentioned in one of my lectures on R. Ben Zion Uziel.[39] While R. Uziel is in many respects a model for a Modern Orthodox posek, it is quite jarring to find that he too takes seriously the claim that a woman was intimate with a demon. Instead of sending her to a psychologist, he devotes great efforts to showing that she can remain with her kohen husband.[40] That poskim would discuss this sort of thing is not surprising, and in an earlier post I mentioned a current talmid chacham who discusses if one can eat the flesh of a demon. Similarly, Sprecher cites a twentieth-century work that deals with circumcising a child whose father was a demon.[41] Yet to find R. Uziel, a supposedly modern posek, also taking this very seriously was quite a surprise to me. I guess the greater surprise was that of the various women involved with the demons. While some were no doubt off their rocker, others presumably just invented the story to save themselves from the shame of an improper relationship and its consequences. Imagine their surprise when instead of being condemned for their illicit affair, the rabbis actually believed the story that they made up, namely, that the man they had sex with was really a demon![42] Once a woman is believed to have had sex with a demon, and certainly if she had a child in this fashion, people are generally not going to want to have anything to do with her and her family. Being descended from the Devil is hardly the best yichus. Yet much of the world began like this, at least according to one early interpretation. Targum Ps.-Jonathan to Gen. 4:1 explains that Cain’s father is not Adam, but Sammael, who also is known as Satan and the Angel of Death. As James Kugel has shown, this tradition is found in other early sources, such as 1 John 3:12 which describes Cain as being “of the Evil One.” Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 21 describes how the serpent impregnated Eve, and we know from other sources that the serpent is none other than Sammael. While we might be inclined to smile and regard this all as pleasant folklore, there is actually much more here than meets the eye. As Kugel brilliantly notes, this portrayal of Cain serves to explain why God did not accept his sacrifice, a point that is never explained in the text. In addition, it helps solve the puzzling comment of Eve (Gen. 4:1): “I have gotten a man with the Lord,” understanding “man” to mean angel, as is elsewhere found in Scripture.[43] Lest one think that in modern times tales of the Devil’s children are only to be found in novels and on the big screen – one immediately thinks of Rosemary’s Baby and The Omen – let me tell you a fascinating story. In the beginning of the nineteenth century a married woman named Yittel Levkovich gave birth to a child which, we are told, was obviously not her husband’s. Yittel claimed that she had been raped by a male demon. This claim was accepted and the woman was not regarded as an adulteress nor was the child regarded as a mamzer. Yet other Jews refused to marry with the descendants of this woman, and these descendants were known as “Chitshers.” Matters got to be so bad that in 1926 a broadside was published signed by many Hungarian rabbis declaring that there was no problem marrying into the Chitshers. Among the signatories was the young R. Joel Teitelbaum, the rav of Satmar. Despite this plea, there were those who continued to shun the Chitchers, and even to this day there are families in the Hungarian hasidic world who will refuse to intermarry with other Hungarian hasidim since the latter are descended from Yittel and the demon. Tying in with the Christian theme with which I began this post, there was even a belief that a Chitcher has the image of a cross under his skin opposite the heart![44] Take a look at the end of this responsum.

This is a fascinating topic, and those who want more details should consult the previously mentioned article by Sprecher, from which I took the information mentioned until now. One aspect of the story that appeared too late to be included by Sprecher is mentioned by Jerome Mintz, and shows how despite R. Yoel Teitelbaum’s words of support for the Chitshers, this did not carry on to one of the inheritors of his throne. Jerome Mintz records the following from a Satmar informant: The Satmar Rebbe’s son, the oldest son, Aaron, he has sometimes a big mouth. Aaron, the Rebbe’s son, gave a speech and he called Ableson’s[45] mother a hatzufah [impudent woman]. “This Ableson’s mother–that impudent woman with her tsiganer [gypsy] family–came to the shul and starts yelling.” You know, with that phrase he was trying to bring up an old pain.

This is a fascinating topic, and those who want more details should consult the previously mentioned article by Sprecher, from which I took the information mentioned until now. One aspect of the story that appeared too late to be included by Sprecher is mentioned by Jerome Mintz, and shows how despite R. Yoel Teitelbaum’s words of support for the Chitshers, this did not carry on to one of the inheritors of his throne. Jerome Mintz records the following from a Satmar informant: The Satmar Rebbe’s son, the oldest son, Aaron, he has sometimes a big mouth. Aaron, the Rebbe’s son, gave a speech and he called Ableson’s[45] mother a hatzufah [impudent woman]. “This Ableson’s mother–that impudent woman with her tsiganer [gypsy] family–came to the shul and starts yelling.” You know, with that phrase he was trying to bring up an old pain.

There is an old story about the Ableson family, given only from mouth to ear, about the quality of their family. There were some rumors about a hundred years ago about the Ableson family, that it’s not so spotless. A woman in the family had a relationship with some demon or something and that’s how the branch of the family got started. . . . Nobody knows how she became pregnant. She went away to a different town and came back pregnant and she didn’t have any love affair. She was a virgin. She was still a virgin. . . . It’s written in a lot of books at that time. The Kotsker, on of the big rabbis, said that one of their ancestors was made pregnant by a demon.

This goes back six generations. The family is spread out and the descendants feel a little guilty. They try to behave, you know, so that nobody should throw it back at them. The family is so widespread because they’re so rich. They’ve gotten into every family. They’re very aggressive people, probably because they come from the devil. . . . Even today when somebody is making a marriage arrangement he wants to find out if the family is not from the witches. I know that my mother and my father when they made a marriage arrangement, it was a day before they left the country, they found out if there’s a witch or not.[46]

The R. Aaron mentioned in this story is one of the current Satmar Rebbes. We find another example where a large family was ostracized in this fashion. The problem here was especially acute as many great Torah scholars had married into this family, and now aspersions were being cast on it. Those casting the aspersions referred to the family members as Nadler, which has the connotation of mamzer. (As with the term mamzer, it was also used as a general term of abuse and is the subject of a responsum of R. Solomon Luria.[47]) Because of the growing calumnies against innocent families, the Maharal and numerous other great rabbis were forced to publicly support them and condemn all who would question their yichus.[48] What I don’t understand is how, considering the base origin of the term “Nadler” and how it was used in such an abusive fashion, that the word actually became an acceptable last name. Indeed, it is now more than acceptable and people are proud to have this name, which they share with two outstanding scholars, not to mention my former congressman. * * * Returning to the issue of Christianity, many have discussed whether or not it is considered avodah zarah. I will deal with this at a future time, but now I want to raise another issue which I mentioned briefly in Limits of Orthodox Theology: What is worse, atheism or avodah zarah? Subsequent to the book’s appearance I found more sources related to this, which I hope to come back to in a future post. For now, let me just call attention to found a very interesting comment of R. David Zvi Hoffmann with regard to avodah zarah. It is found in R. Hayyim Hirschenson’s journal, Ha-Misderonah 1 (1885), p. 137. In speaking about the practice of the Talmud to sometime use euphemistic language, he claims that the expression “Grave is avodah zarah, for whoever denies it is as if he accepts the whole Torah” (Hullin 5a and parallels) is an example of this. In other words, the Talmud really means: “Grave is avodah zarah, for whoever accepts it denies the entire Torah.” I had never thought of this and it is certainly interesting. Hoffmann is himself led to this interpretation, which he sees as obvious, because if it was really the case that one who rejected avodah zarah would be regarded as one who accepts the Torah, how come a public Sabbath violator who rejects avodah zarah is still regarded as having rejected the Torah? Nevertheless, despite its immediate appeal, I don’t think Hoffmann’s interpretation can be accepted, and the passage is not to be regarded as euphemistic. Rather, it is an example of the Sages’ exaggerations, which we find in other places as well, such as where they state that a certain commandment is equal to all six hundred thirteen. In fact, I have what I think is conclusive proof that Hoffmann is mistaken in regarding this passage as expressing a euphemism. In Megillah 13a the passage appears in an altered form: “Anyone who repudiates avodah zarah is called ‘a Jew.'” The Talmud then cites a biblical proof text to support this statement which shows that it was not meant to be understood as a euphemism. While on the subject of Christianity, I would like to respond to the reaction of some who read my opinion piece on John Hagee. There I showed that what got so many upset, namely, Hagee’s theological understanding of the Holocaust, was actually shared by R. Zvi Yehudah Kook.[49] Of course, I understand why people feel that attempting to explain the Holocaust is improper. I happen to share this sentiment. Yet if people are upset by what Hagee said, just wait until they see the following, which out of all the supposed justifications for the Holocaust, which have ranged the gamut, this is surely the most bizarre. What can I say, other than that it never ceases to amaze me how some of the greatest scholars we have say some of the craziest stuff imaginable. I am referring to one of the reasons R. Ovadiah Hadaya gives to explain the Holocaust. He saw it as God’s way of cleansing the world of all the mamzerim![50] How a sensitive scholar, which Hadaya certainly was,[51] could offer such an explanation really boggles the mind. To think that the cruel murder of six million, including over a million children, not to mention all of the other terrible results of the Holocaust, was in order to complete some yichus program is beyond strange. I can’t recall who it was who said that any attempts at explaining suffering are invalid if you are not prepared to tell it to a parent whose child is dying of cancer. I certainly can’t imagine anyone telling a parent that his family was wiped out in the Holocaust in order to get rid of the mamzerim! (A well-known American haredi rosh yeshiva responded very strongly when told about what Hadaya wrote, but I don’t have permission to quote his words.) Prof. David Halivni commented, when I told him about Hadaya’s view, that Sephardim often don’t get it when it comes to the Holocaust. I remember thinking about Halivni’s comment when R. Ovadiah Yosef gave his own explanation for the Holocaust, some years ago, one which created such a storm that Holocaust survivors protested outside his home. He claimed that the dead were really reincarnated souls suffering for their sins in previous lifetimes. Although he doesn’t mention it, Hadaya’s view is obviously based on the Jerusalem Talmud, Yevamot 8:3, which speaks of a catastrophe coming on the world every few generations which destroys both mamzerim and non-mamzerim (the latter are destroyed as well, so that it not be known who committed the sin.) Sefer Hasidim, ed. Margaliot, no. 213, repeats this teaching. יש הריגת דבר או חרב שלא נגזר אלא לכלות הממזרים וכדי שלא לביישם שאם לא ימותו רק הממזרים היה נודע והיתה המשפחה מתביישת מפני חברתה [ולכן נוטל הכשרים עמהם] It is with regard to the issue of the mamzer that one can see manifested a point I have often thought about. The great classical historian Moses Finley spoke of what he termed the “teleological fallacy” in the interpretation of historical change. “It consists in assuming the existence from the beginning of time, so to speak, of the writer’s values . . . and in then examining all earlier thought and practice as if they were, or ought to have been, on the road to this realization, as if men in other periods were asking the same questions and facing the same problems as those of the historian and his world.”[52] The fact is that earlier generations often thought very differently about things. For example, we are much more sensitive to matters such as human rights than they were. They took slavery for granted, while the very concept of owning another person is the most detestable thing imaginable to us. Followers of R. Kook will put all of this in a religious framework, and see it as humanity’s development as it gets closer to the Messianic era. We see this very clearly when it comes to the issue of the mamzer who through no fault of his own suffers terribly. The Orthodox community is very sympathetic to his fate, and it is unimaginable that people today will, as in the past express satisfaction at the death of a mamzer.[53] A difficulty with the sympathetic approach is the Shulhan Arukh‘s ruling (Yoreh Deah 265:4) that when the mamzer is born אין מבקשים עליו רחמים. The Shakh writes: כלומר אין אומרים קיים את הילד כו’, מטעם דלא ניחא להו לישראל הקדושים לקיים הממזרים שביניהם. In fact, according to R. Bahya ibn Paquda (Hovot ha-Levavot, Sha’ar ha-Teshuvah, ch. 10), if one is responsible for bringing a mamzer into the world, and then does a proper teshuvah, “God will destroy the offspring.” Needless to say, if a modern person believed this to be true, it hardly would encourage him or her to do teshuvah.[54] (Philippe Ariès could perhaps have cited this text in order to bolster his controversial thesis that medieval parents were indifferent to their children, as it is unimaginable that a contemporary preacher would tell parents that the result of their teshuvah would mean the death of their child.) What, from today’s standards, would be the most cruel thing imaginable, is described by R. Ishmael ha-Kohen of Modena, the last great Italian posek (Zera Emet 3:111).[55] R. Ishmael rules that the word “mamzer” should be tattooed (by a non-Jew) on a mamzer baby’s forehead![56] This will prevent him from being able to marry. I know that no contemporary rabbi would recommend such a step (although the Zera Emet‘s advice is quoted in R. Zvi Hirsch Shapira’s Darkhei Teshuvah, Yoreh Deah 190:11). Nor would anyone want the mamzer’s house or grave to be plastered, as was apparently the opinion of some in talmudic days, in order that people would be able to shun him.[57] This leads to an issue that would require an entire volume to adequately deal with it. This volume would trace the Orthodox confrontation with changing values and show how Orthodox practices and ideas have responded. It is obvious that there is much more in the way of reevaluation of prior ideas in the Modern Orthodox world, but there is also a great deal in the haredi world as well. As noted already, I have observed this personally when haredi figures, and not only of the kiruv variety, have asserted that certain ideas and concepts are in opposition to Jewish values, and have then been flustered when I showed them that great figures of the past have actually put forth what today is regarded, even in the haredi world, as immoral statements. Examples of this are easy to find. R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg pointed to one: the Rambam’s ruling in Issurei Biah 12:10. I am reluctant to spell this out here, because I know how it could be used by anti-Semites, so let me just quote it in Hebrew. ישראל שבא על הגויה–בין קטנה בת שלוש שנים ויום אחד [!] בין גדולה, בין פנויה בין אשת איש, ואפילו היה קטן בן תשע שנים ויום אחד–כיון שבא על הגויה בזדון, הרי זו נהרגת מפני שבאת לישראל תקלה על ידיה, כבהמה. I don’t think that there is any sane person in the world, no matter what community he is in, who would advocate this in modern times.[58] Furthermore, if you defend, even in the most right wing community, what Maimonides says here with regard to an innocent child, you will be regarded as evil. The traditional commentators are at a loss to explain where Maimonides got this. This example was pointed to by Weinberg as one of the traditional passages which most distressed him. Let me give another example which again illustrates how often contemporary moral judgments are far removed from those of previous generations, even when dealing with great Jewish leaders. R. Zvi Hirsch Chajes claims that a king has the right to kill the innocent children of someone who rebels, because of tikun olam,[59] and the Hatam Sofer, in a letter to Chajes, find this a reasonable position.[60] The purpose of the killing would be to put fear into others, who while may be willing to risk their own lives in rebellion, would be deterred if their families were wiped out. This is certainly not what anyone today would regard as “Jewish values.”[61] In fact, Seforno, Netziv, and Meshekh Hokhmah, in their commentaries to Deut. 24:16 (“Children shall not be put to death for the fathers”), specifically reject this possibility, with Seforno noting how this was a typical Gentile practice that the Torah is legislating against.[62] In such a case, we have to follow the guidance of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, who believed that if there is a dispute among halakhic authorities, the poskim must reject the view that will bring Torah into disrepute in people’s eyes (Kitvei ha-Gaon Rabbi Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, vol. 1, p. 60): ואגלה להדר”ג [הגרא”י אונטרמן] מה שבלבי: שמקום שיש מחלוקת הראשונים צריכים הרבנים להכריע נגד אותה הדעה, שהיא רחוקה מדעת הבריות וגורמת לזלזול וללעג נגד תוה”ק R. Shlomo Aviner has the same approach (Am ve-Artzo, vol. 2, pp. 436-437) . He refuses to say that any rishon was less moral than another, but he notes that conceptions of morality change over time and not every decision of a posek is an eternal decision. Today, when we have different standards of morality than in previous days. If there is a dispute among the authorities, we should adopt the position which we regard as more moral. וברור שבהלכה פנים לכאן ולכאן. לכן כיוון שנתיבים אלה הם נתיבים מוסריים יותר, עלינו להכריע על פיהם. לפעמים ההלכה מוכרעת, בגלל שעת הדחק, ולפעמים ההלכה מוכרעת כי כך המנהג. אם כן, בימינו ‘המנהג’ הוא להיות מוסרי . . . יש גם מושגים מוסריים המשתנים על פי המציאות. אב הסוטר לבנו הקטן, אינו דומה לאב הסוטר לבנו בן השמונה עשרה. האם סטירת לחי לבנו היא מעשה מוסרי או לא מוסרי? תלוי בנסיבות. לא כל הכרעות הפוסקים הן הכרעות נצחיות . . . במצבנו כיום ישנם שיקולים מוסריים שמצטרפים להכרעותינו ההלכתיות In a recent by book by R. Yuval Sherlo, Reshut ha-Rabim, p. 102, he acknowledges moral advancement and concludes: “Despite all the hypocricy and cynicism there is moral progress in the area of human rights. True religious people believe that this is the will of God.” All this stands in opposition to R. J. David Bleich’s incredible statement: “The halakhic enterprise, of necessity, proceeds without reference or openness to, much less acceptance or rejection of, modernity. Modernity is irrelevant to the formulation of halakhic determinations” Contemporary Halakhic Problems (New York, 1995), vol. 4, p. xvii (emphasis added). This statement is wrong on so many levels that I am inclined to think that Bleich simply didn’t express himself properly and meant to say something other than what appears from his words. In any event, in a future post I will return to Bleich’s controversial understanding of the halakhic process. As to the general problem of laws that trouble the ethical sense of people, we find that it is R. Kook who takes the bull by the horns and suggests a radical approach. The issue was much more vexing for R. Kook than for other sages, as in these types of matters he could not simply tell people that their consciences were leading them astray and that they should submerge their inherent feelings of right and wrong. It is R. Kook, after all, who famously says that fear of heaven cannot push aside one’s natural morality (Shemonah Kevatzim 1:75): אסור ליראת שמים שתדחק את המוסר הטבעי של האדם, כי אז אינה עוד יראת שמים טהורה. סימן ליראת שמים טהורה הוא, כשהמוסר הטבעי, הנטוע בטבע הישר של האדם, הולך ועולה על פיה במעלות יותר גבוהות ממה שהוא עומד מבלעדיה. אבל אם תצוייר יראת שמים בתכונה כזאת, שבלא השפעתה על החיים היו החיים יותר נוטים לפעול טוב, ולהוציא אל הפועל דברים מועילים לפרט ולכלל, ועל פי השפעתה מתמעט כח הפועל ההוא, יראת שמים כזאת היא יראה פסולה. These are incredible words. R. Kook was also “confident that if a particular moral intuition reflecting the divine will achieves widespread popularity, it will no doubt enable the halakhic authorities to find genuine textual basis for their new understanding.”[63] R. Kook formulates his idea as follows (Iggerot ha-Reiyah, vol. 1, p. 103): ואם תפול שאלה על איזה משפט שבתורה, שלפי מושגי המוסר יהיה נראה שצריך להיות מובן באופן אחר, אז אם באמת ע”פ ב”ד הגדול יוחלט שזה המשפט לא נאמר כ”א באותם התנאים שכבר אינם, ודאי ימצא ע”ז מקור בתורה. R. Kook is not speaking about apologetics here, but a revealing of Torah truth that was previously hidden. The truth is latent, and with the development of moral ideas, which is driven by God, the new insight in the Torah becomes apparent.[64] In a volume of R. Kook’s writings that appeared in 2008, he elaborates on the role of natural morality) Kevatzim mi-Ketav Yad Kodsho, vol. 2, p. 121 [4:16]): כשהמוסר הטבעי מתגבר בעולם, באיזה צורה שתהיה, חייב כל אדם לקבל לתוכו אותו מממקורו, דהיינו מהתגלותו בעולם, ואת פרטיו יפלס על פי ארחות התורה. אז יעלה בידו המוסר הטהור אמיץ ומזוקק. Another interesting statement from R. Kook on developing morality is found in Pinkesei ha-Reiyah, also published in 2008. (In a future post I will have more to say about these two new volumes.) In discussing how terrible war is, and the concept of a “permissible war,” which is recognized as a halakhic category, he notes that the latter is only suitable for a world which hasn’t developed properly, one which still sees war as a means to achieve things, This proper development can only come when all peoples have reached an elevated stage, since, pace Gandhi, you can’t have one nation practice the higher morality of no war while other nations are still using force. R. Kook describes “permissible war” as follows (p. 29): כל התורה הזאת של מלחמת רשות לא נאמרה כ”א לאנושיות שלא נגמרה בחינוך. The way the Torah shows this is by the law of yefat toar, concerning which R. Kook writes: כל לב יבין על נקלה כי רק לאומה שלא באה לתכלית חינוך האנושי, או יחידים מהם, יהיה הכרח לדבר כנגד יצר הרע ע”י לקיחת יפת תואר בשביה באופן המדובר. ומזה נלמד שכשם שעלינו להתרומם מדין יפת תואר, כן נזכה להתרומם מעיקר החינוך של מלחמת רשות, ונכיר שכל כלי זיין אינו אלא לגנאי. Wouldn’t it be great to hear rabbis talk about stuff like this on Shabbat?! On the very next page of Pinkesei ha-Reiyah, R. Kook applies the same insight to the issue of slavery, seeing it as only a temporary phenomenon, one that the Torah wishes to see done away with. In addition to what I have quoted from him in note 64, R. Norman Lamm has also recently written something else relevant to the issue being discussed: If anyone harbors serious doubts about inevitable changes in the moral climate in favor of heightened sensitivity, consider how we would react if in our own times someone would stipulate as the nadan for his daughter the equivalent of the one hundred Philistine foreskins which Saul demanded of David (1 Samuel 18:25) and which dowry David later offered to him for his daughter Michal’s hand in marriage (II Samuel 3:14) . . . The difference in perspective is not only a matter of esthetics and taste but also of morals.[65] He then develops the notion of a developing halakhic morality in which our evolving understanding of morality lead us back to the Torah “to rediscover what was always there in the inner folds of the Biblical texts and halakhic traditions” (pp. 226-227). To be continued * * * Many of you reading this post have purchased my book Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters. In the first printing there is an unfortunate typo in the very last word (there are also some typos in the Hebrew section). Although I read through the book a few times before printing, as did a copy-editor, we didn’t notice it. Neither did numerous others who read the book, and I thank R. Yoel Catane, the editor of Ha-Ma’ayan, who was the first to catch the mistake (which has been fixed in the new printing). While the last word reads ,מחמר this should actually be מחמד, and was understood to refer to Muhammad. I was very upset upon learning of the careless typo. Seeing how I was beating myself up, my friend Shlomo Tikoshinski wrote to me as follows: לאו דמחמר – אין לוקין עליו (see Shabbat 154a, Mishneh Torah, Hilkhhot Shabbat 20:1)

[33] See Isaiah Tishby, Netivei Emunah u-Minut (Jerusalem, 1982), pp. 228ff.[34] She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rashbash, no. 411.

[35] See Daniel J. Lasker, Jewish Philosophical Polemics Against Christianity in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2007), pp. 81-82.

[36] See Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief (Chicago, 2002), ch. 3.[37] See Thomas E. Bullard, UFO Abductions (Mount Ranier, MD, 1987). See also Jonathan Z. Smith’s article “Close Encounters of Diverse Kinds,” reprinted in his Relating Religion (Chicago, 2004), ch. 13.

[38] “Diabolus Ex-Machina: An Unusual Case of Yuhasin,” Jewish Law Association Studies 8 (1994), pp. 183-204.[39] Available at torahinmotion.org[40] Mishpetei Uziel,Mahadurah Tinyana, Even ha-Ezer no. 11.[41] Yalkut Avraham (Munkacs, 1931), p. 10.[42] While it is clear that demons come in both male and female, what about angels? According to the Magen Avraham, Orah Hayyim 610:5, the reason only men wear white on Yom Kippur is because men want to appear like the angels, and angels are male! Magen Avraham didn’t make this up, but is quoting a Midrash which teaches this idea. See Yalkut Shimoni, Proverbs 959, and Louis Jacobs, Judaism and Theology (London, 2005), ch. 19.[43] See The Bible as it Was (Cambridge, 1997), p. 86; How to Read the Bible (New York, 2007), pp. 60-61[44] R. Asher Anshel Miller, Hayyei Asher (Bnei Brak, 1991), no. 123.

[45] Mintz tells us that this is a pseudonym. For details of the conflict between “Yosel Ableson” and R. Aaron, see Mintz, Hasidic People (Cambridge, MA., 1992), pp. 302ff.

[46] Ibid., p. 307.[47] See the testimony recorded She’elot u-Teshuvot Maharshal, no. 101:דוא בישט איין נאדלר. דוא נאדלר ווארום נימשטו מיר מיין געלט . . . [48] See R. Judah Loew ben Bezalel, Netivot Olam (Bnei Brak, 1980), Netiv ha-Lashon, ch. 9.[49] See here[50] Yaskil Avdi, vol. 8, p. 200.[51] See e.g., his responsum in R. Ovadiah Yosef, Yabia Omer, vol. 3 p. 300. Here he reminds dayanim not to lose site of the humanity of the people standing before them (which current dayanim voiding conversions seem to forget–I will return to this in an upcoming post):

על הדיין לראות מעצמו אם היה ענין כזה באחת מבנותיו ח”ו, ובא הבעל נגדה בטענה כזו, האם ירצה שביה”ד יפסקו עליה להוציאה בע”כ מבלי כתובה. [52] Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology (London, 1980), p. 17.[53] See e.g., Maharil, Hilkhot Milah no. 20:וצוה הרב לשמש העיר להכריז אחר המילה לציבור קול רם תדעו הכל שהילד הנימול הוא ממזר . . . ואמר אלינו מהר”י סג”ל שנתגדל הנער ההוא לבן עשר שנים ומת. וכתבו למהרי”ל לבשורה טובה שנסתלק ונאסף מתוכנו

R. Israel Moses Hazan, Kerakh shel Romi, p. 61b:ועברו איזה ימים ומת הממזר (ברוך שעקרו ולא נתערב זרע ממזרים בתוך קהלתנו)

R. Elijah Aberzel rules that it is permitted to abort a mamzer fetus. See Dibrot Eliyahu, vol. 6, no. 107.

[54] For an example of a preacher’s words that even the most idiotic person today would never use in trying to comfort a bereaved parent, see R. Joseph Stadthagen Divrei Zikaron (Amsterdam, 1705), p. 38a:ואם ח”ו מזבח כפרה מיתת בנים יארע, גם בזה אין ראוי להצטער [!] כי מי יודע מה היה מגדל ממנו יצור או כיעור, חכם או סכל, להרע או להטיב. [55] For those who have never heard of R. Ishmael, consider this: He is quoted by R. Ovadiah Yosef in Yabia Omer and Yehaveh Da’at many more times than R. Moses Feinstein.[56] In those days mamzerim were also named kidor, based on Deut. 32:20: כי דור תהפוכות המה[57] See Meir Bar–Ilan, “Saul Lieberman: The Greatest Sage in Israel,” in Meir Lubetski, ed., Saul Lieberman (1898-1983), Talmudic Scholar (Lewiston, 2002), pp. 86-87 (referring to Tosefta Yevamot, ch. 3).

[58] In his Avi Ezri R. Shakh discusses a certain halakhah dealing with the death penalty for violating the Noahide commandments. In 1987 some (presumably Chabad) troublemakers, obviously not concerned about hillul ha-Shem, “leaked” this to Israeli newspapers with the result that the latter had headlines: הרב שך מתיר להרוג גויים ללא דין. R. Shakh’s people were quick to point out that the discussion in Avi Ezri is completely theoretical, something which the “leakers” were well of. See Moshe Horovitz, She-ha-Mafteah be-Yado (Jerusalem, 1989), 96ff. For a similar incident five years ago involving Yeshiva University, see “Critics Slam Rabbi, Y.U. Over Article on Gentiles,” available here

[59] Torat ha-Nevi’im, ch. 7.[60] She’elot u-Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, Orah Hayyim no. 108 (end).[61] Cf. however Nathan Lewin’s argument, “Deterring Suicide Kllers,” available here Lewin, however, is dealing with adults, not potentially minor children. For Arthur Green’s response, ” A Stronger Moral Force,” see here

[62] See R. Shimon Krasner, “Ishiyuto u-Feulotav shel Shaul ha-Melekh,” Yeshurun 11 (2002), pp. 779-780.

[63] Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah (Waltham, 2004), p. 292 n. 38.

[64] Cf. this to what R. Norman Lamm wrote in his response to Noah Feldman’s infamous article, referring in particular to Feldman’s discussion of the saving of non-Jewish life on Shabbat.Surely you, as a distinguished academic lawyer, must have come across instances in which a precedent that was once valid has, in the course of time, proved morally objectionable, as a result of which it was amended, so that the law remains “on the books” as a juridical foundation, while it becomes effectively inoperative through legal analysis and moral argument. Why, then, can you not be as generous to Jewish law, and appreciate that certain biblical laws are unenforceable in practical terms, because all legal systems — including Jewish law — do not simply dump their axiomatic bases but develop them. Why not admire scholars of Jewish law who use various legal technicalities to preserve the text of the original law in its essence, and yet make sure that appropriate changes would be made in accordance with new moral sensitivities? [65] “Amalek and the Seven Nations: A Case of Law vs. Morality,” in Lawrence Schiffman and Joel B. Wolowelsky, eds., War and Peace in the Jewish Tradition (New York, 2007), p. 208.

Thoughts on Confrontation & Sundry Matters Part I

Soloveichik is currently working on his PhD at Princeton, and due to his many essays he has already made a mark. While it is true that political concerns play a central role in his writing, and he seems most comfortable in the role of public intellectual rather than academic scholar, there is a great deal of learning in everything that he produces. He has also emerged as Orthodoxy’s most prominent “theocon,” which has led him to take positions that in my opinion are at odds with the proper halakhic response.[4] I also suspect that many will not look kindly upon his theoretical defense of torture, although no one can argue the case better than he can.[5]

There are those who will criticize Soloveichik because he engages in theological dialogue with Christians, and they think that this is in violation of the Rav’s strictures. If that were the case, then the Rav himself would be in violation, because he first delivered his famous “Lonely Man of Faith” as a lecture at a Catholic seminary.[6] The fact is that the Rav never said that theological issues couldn’t be discussed with non-Jews in a non-official setting. It all depends on the context of the discussions and the venue. In any event, it is very important to have a rabbi who actually understands Christian dogma. Otherwise, you can get poskim, like R. Joseph Messas, mentioned below, who come to decisions based on entirely incorrect information.

We should all be happy that there is a rabbi who knows that before Newman was an actor and then a tomato sauce, there was a more important Newman, that Immaculate Conception is not Virgin Birth, that Limbo is not only a game played at Bar Mitzvahs, and that St. Thomas is more than an island in the Caribbean. There are, however, many rabbis who know very little about Christianity. That is fine, but it is not fine when they try to speak about a matter they know nothing about. Some time ago I heard a talk in which the speaker gave his take on what was wrong with certain Christian ideas. The only problem was that that he had but a smattering of knowledge of the religion he was discussing. (Can you believe that there are people who speak about Catholicism without even knowing what happened at Vatican II?) After the talk someone asked me what I thought about the speaker. My reply was to quote the immortal words of Ha-Gaon R. Mizrach-Etz: “A man has got to know his limitations.”[7]

Let me begin with a short article I wrote on “Confrontation” that originally appeared on the website of Boston College’s Center for Jewish-Christian Understanding. I don’t think that many people have seen it, and posting it here will give it some more exposure. I would encourage people to also read the other papers.[8] One can even watch the original presentations.[9] “Confrontation”: A Mixed Legacy If any evidence were needed of the centrality of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik in contemporary American Orthodoxy, one need only look at the vigorous exchange of ideas between Drs. Korn, Berger and Rabbi Klapper. These thinkers have focused on a close reading of the seminal essay “Confrontation,” and have argued about its message and implications in a changed world. I would like to call attention to some points that have not been raised, which I regard as unfortunate results of the widespread acceptance in American Orthodoxy of the perspective offered in “Confrontation.”

My goal in these comments is not to criticize the essay, but rather to clarify its impact. In fact, both in my personal and professional life (with perhaps one exception) I have avoided all venues of interfaith dialogue, and this despite being in my tenth year of teaching at a Jesuit university. I have participated in numerous events where Christians were exposed to Judaism, as well as some where I learnt more about Christianity, but it is unlikely that Rabbi Soloveitchik’s position has any relevance to these situations.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s warning was directed against Jews dialoguing with Christians in some sort of organized, presumably official,[10] meeting, and the fears he expressed relate to this type of setting. On the other hand, individual Jews and Christians discussing each other’s religion has occurred in every generation, and neither this, nor a Jew giving a lecture to Christians about some aspect of Judaism, qualifies as dialogue of the sort that the Rav was warning against. It is therefore not surprising that even the most strident opponents of dialogue do not mention the subject of Orthodox professors teaching at universities whose student body is primarily Christian.

I have abstained from involvement in interfaith dialogue not because I regard the Rav’s essay as a binding halakhic decision, but because I would have felt uncomfortable being regarded by the other side as a representative of Judaism. (Despite being part of a department of Theology and Religious studies, I am hardly a theologian.) In addition, I have always been sensitive to an aspect of dialogue that the Rav was concerned with, namely, that Jews will feel pressure to adjust their religious views in response to moves from the Christian side. In calling attention to this point, I feel that the Rav was uncannily prescient.

Yet despite the fact that I have lived my life in accordance with the Rav’s guidelines, I believe that his position has had certain negative consequences. It might be that these are the sorts of consequences that Orthodox Jews who follow the Rav’s prescriptions must live with, but I hope not.

One of these consequences is religious separatism, and when it comes to interfaith relations the Modern Orthodox have adopted the same position as that of the right-wing Orthodox. Thus, in the United States one finds virtually no relationships between Modern Orthodox rabbis and Christian clergymen, or between Modern Orthodox groups and their Christian counterparts, even of the sort that the Rav would encourage.[11] This type of separatism is to be expected when dealing with the haredim, but one would have thought that the rabbinic leadership of Modern Orthodoxy would be more open-minded in this area. Yet for many Modern Orthodox rabbinic figures this is not the case, and when a group of Cardinals recently toured Yeshiva University a number of faculty members and students of the Rav expressed strong criticism of the administration in allowing this visit.[12] In fact, the Rav was often cited as a source for this opposition, as if anything he wrote in “Confrontation” spoke against friendly relations and interchange of ideas in non-theological settings.[13]

In today’s Orthodox world, when it comes to Christianity the stress is on the negative, beyond anything the Rav wrote about in “Confrontation.” This has brought about a broad refusal on the part of Modern Orthodox rabbis to have even the barest of relationships with their Christian counterparts. I am not blaming this on “Confrontation,” since before the essay appeared such relationships were also rare, but the essay reinforced the atmosphere of distance between Orthodox Jews and Christians in all spheres, even though this was not its intent. To put it another way, I would say that, despite its intent, “Confrontation” reaffirmed Orthodox Jews’ inclination that, in all but the most negligible circumstances, they should ignore the dominant religion and its adherents. A different essay by the Rav could have put an even greater stress on the positive results of interfaith cooperation in “secular” spheres.[14] Instead, almost nothing was done to remove the fear of Christianity from Orthodoxy, and while in the very shadow of Vatican II this might have been the correct approach, by now I think we have moved beyond this. Yet even in our day it would still be unheard of for a Christian clergyman to address the members of an Orthodox synagogue or group about matters of joint concern. A lay Christian might be welcome, but any relationship with clergy is seen as dangerous, in that it could lead to a compromising of traditional Jewish beliefs.

Another result of the lack of any dialogue between Orthodox Jews and Christians is that in addition to the fear of Christianity, there remains an enormous amount of ignorance. On numerous occasions I have heard Orthodox Jews assert that according to Christianity one must accept Jesus in order to be “saved”. When I have pointed out that this notion has been repudiated by the Catholic Church as well as by most Protestants, the response is usually incredulity.

It is also significant that Orthodox Jews treat Christianity as an abstraction, and detailed discussions about its halakhic status continue to be published. I find it strange, however, that in our post-modern era people can write articles offering judgments about Christianity based solely on book knowledge,[15] without ever having spoken to Christian scholars and clergymen, that is, without having ever confronted Christianity as a living religion.[16] There is something deeply troubling about Orthodox figures discussing whether Christianity is avodah zarah without attempting to learn from Christians how their faith has impacted their lives. I would think that this narrative, attesting as it does to the redemptive power of faith, must also be part of any Jewish evaluation of Christianity.[17] Yet barring theological dialogue, how is this possible?

I realize that the halakhic system prefers raw data to experiential narratives, but certainly modern halakhists and theologians are able to find precedents for inclusion of precisely this sort of information. After all, wasn’t it personal contact with Gentiles, and the recognition that their lives were not like those of the wicked pagans of old, that led to a reevaluation of the halakhic status of the Christian beginning with Meiri and continuing through R. Israel Moses Hazan,[18] R. David Zvi Hoffmann, and R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg?

The concern with dialogue leading to attempted revisions of traditional Jewish beliefs is certainly well-founded, but the flip-side is that without any direct contact distortions can arise in the other direction as well, namely, in how non-Jews are viewed. Could Saadia Grama ever have written his infamous book[19] if his Gentile neighbor, the Christian, was a real person instead of a caricature? Of course, one does not need interfaith theological dialogue in order to see adherents of other religions in a more positive light than Grama, but as noted above, a current trend opposes even non-theological dialogue. When all substantive contact with the Other is off-limits, it becomes much easier for extremists to reawaken old prejudices that should have no place in a modern democratic society.

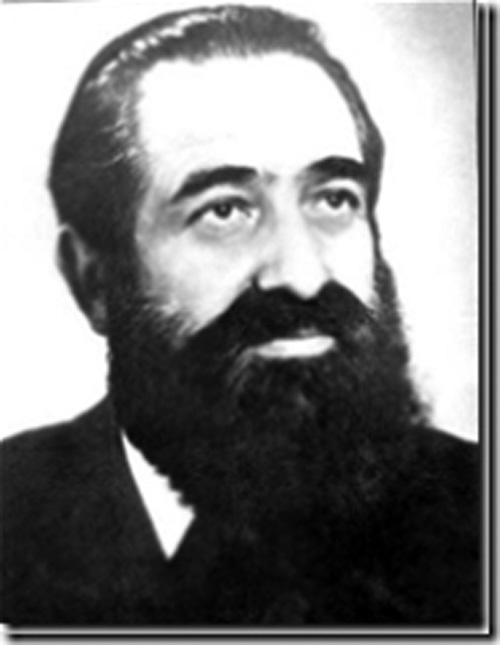

I don’t have any illusions that the leaders of American Orthodoxy will change their stance on this matter even after considering what I and others have written. Yet this does not mean that all is lost when it comes to Jewish-Christian relations. Even without theological dialogue there is still a great deal that we can discuss, and thus ensure that neither Orthodox Jews nor Christians are strangers in each other’s eyes. There is a host of social and political issues that affect both of our communities and a vast reservoir of goodwill and respect among Christians for Jews, and Orthodox Jews in particular. Isn’t it time the Orthodox responded in kind?* * *With regard to the Rav and Christianity, it is interesting to note what R. Samuel Volk wrote. R. Volk was one of the other roshei yeshiva at RIETS, an outstanding talmudist who had studied in Telz. Yet he was no fan of the Rav and went so far as to accuse the latter of adopting Christian imagery. In his eulogy for Dr. Samuel Belkin, the Rav described the latter as a wandering and restless yeshiva student. This was too much for Volk (who clearly had a bone to pick with the Rav). In the introduction to volume 7 of his Sha’arei Tohar, he wrote: ראשית כל הנני להעיר שהביטוי הזה של “נודד” שאל “גאון” זה מהגוים ימ”ש, שאומרים שבעבור שעם ישראל לא קבלו תורת “אותו האיש” נתקללו להיות “עם נודד לעולם” ימ”ש וזכרם. ועליהם אין להתפלא דמה לנו ולהם? אבל על “גאון” הנ”ל שיש לו אפי’ “פאספארט” של זכות אבות יש להתפלא! He repeats this criticism of the Rav in his Sha’arei Tohar, vol. 8, p. 332.[20] Yet this is nothing compared to how he savages Dr. Belkin, his former boss. Out of respect for Belkin, I will refrain from reproducing what he writes (which can be found in the just mentioned sources). His words are a good reflection of the conflict and tension that existed between Belkin and the roshei yeshiva, many of whom saw Belkin’s goals as at odds with Torah Judaism[21] On occasion Belkin had to give in to them, as in their threat to resign en masse if he went through with his plan to move Stern College uptown near Yeshiva University. Yet they usually had to sit by and feel growing anger at what they viewed as Belkin’s wrong-headed moves. It was only after they were no longer employed at YU that they could express themselves openly. When they did, it is not surprising that they could be sharper than the most harsh haredi critics. Another strong attack on Belkin was penned by R. Chaim Dov Ber Gulevsky, who also taught at YU. (I will have a great deal more to say about his fascinating writings in one of my upcoming posts.) As with Volk, Gulevsky too, unfortunately, falls into the trap of attacking Belkin personally.[22] In the case of Gulevsky, I can say that he believed that in doing so he was defending the honor of the Rav, for whom he has the greatest respect. Yet, as with Volk, his attack is way overboard, so much so that I am again embarrassed to cite it. It is unfortunate that rather than focusing on all the Torah he taught while at YU, Gulevsky concludes on the following note: ואני תפילה שנזכר לחיים טובים ממלך חפץ בחיים אמן ואמן. ושלא יענישו ושלא ירחיקו אותי ממקורי, וממחיצת צדיקים ישרים ותמימים גאוני ישראל קדושי עליונין בגלל שפעם הייתי במחיצתו של “אותו הנשיא”, “אשר מכף רגל והראש לא היה בו מתום” . . . ר”ל. In Gulevsky’s attack, we also see reflected the long battle between the roshei yeshiva and the adherents of academic Jewish scholarship. This dispute was found at the institution from its early years, and is described in Rakefet’s biography of Revel, Solomon Zeitlin was probably the first focus of the roshei Yeshiva’s anger. A number of others, most notably Irving Agus and Meir Simhah Feldblum, would later run into trouble from the halls of RIETS on account of their outlooks. In Gulevsky’s mind, Belkin was not an adherent of Torah study of the traditional sort – he even denies the well-known story that Belkin received semikhah from the Hafetz Hayyim at age seventeen. He sees Belkin as having sold his soul to the idolatry of academic Jewish studies, with all the heresy that went along with it. In fact, it is not merely academic Jewish studies that Gulevsky sees as Belkin’s downfall, but no less than the hated ‘hokhmah yevanit” that the Sages had warned about. Philo of Alexandria is, in Gulevsky’s understanding, just another example of “hokhmah yevanit.”[23] This involvement with Greek wisdom also led Belkin to his friendships with Christian scholars and “the professor who thought that ‘the Jews made a terrible mistake’ in pushing away oto ha-ish r”l”. Gulevsky told me that (as I suspected) the unnamed professor is Harry A. Wolfson, who was the preeminent Philo scholar of his time. Yet I don’t think Wolfson ever said this, and I believe Gulevsky has confused Wolfson with Joseph Klausner. Gulevsky also recalls with pain how, in his annual shiur in memory of R. Yitzhak Elhanan Spektor, for whom RIETS was named, Belkin would include material dealing with Philo rather than give a traditional shiur. According to Gulevsky, this even led Belkin to make heretical statements with regard to the Oral Law. He also blasts Belkin’s lengthy article on Philo and Midrash Tadshe[24] and what he regards as Belkin’s foolish attempt to posit a Philonic influence on the Zohar through an ancient midrashic tradition.[25] Rather than seeing this last article as a worthy attempt to uphold an ancient dating for the Zohar, Gulevsky instead points out how Scholem rejected Belkin’s position as completely nonsensical, even doing so on a visit to Yeshiva University.[26] * * * Returning to the issue of Judaism and Christianity, let me begin by calling attention to some curiosities that are perhaps not so well known. The first relates to R. Israel Moshe Hazan, mentioned above. His positive view of Christian scholars seemed so over the top to R Eliezer Waldenberg, that the latter delivered a stinging rebuke in Tzitz Eliezer 13:12: שומו שמים למקרא מה יפית כזה לאמונת הנוצרים וחכמיהם מפורש יוצא וללא כל בושה, מפי בעל התשובה . . . ובכלל המותר לקרוא קילוס לחכמיהם? ואיה האיסור של לא תחנם שישנו בדבר? As far as I know, Hazan is the only rabbinic author to publish a Christian haskamah in his work (he actually publishes two). These appear in his Nahalah le-Yisrael, which is devoted to a halakhic problem dealing with inheritance. Translations of these haskamot are found in the appendix to Isadore Grunfeld’s The Jewish Law of Inheritance.[27] (The section dealing with Hazan and his Nahalah le-Yisrael is called: “A Cause Célèbre, A Remarkable Man and a Remarkable Book.”) The Christian scholars’ haskamot appear together with the haskamot of such renowned figures as R. Hayyim David Hazan of Izmir (later Rishon le-Zion in Jerusalem), R. Eleazar Horovitz of Vienna, R. Shimon Sofer of Mattersdorf, R. Avraham Samuel Sofer of Pressburg, and R. Meir Ash of Ungvar. Hazan’s testimony about Jews who would go to the Church to listen the music, even if they stood outside the sanctuary has also been very troubling for many. The whole question of the propriety of entering a church deserves its own post. In years past no Jew would enter a Church unless he was forced to, or in order to avoid enmity. R. Moses Sitrug, Yashiv Moshe, vol. 1, no. 235, discusses the latter case and he advises removing one’s head covering before entering the church. If not, one will be forced to do so in the church, and this would appear as if one was worshipping with the Christians.[28] (When the Chief Rabbi of England is present in a church for an important state function, he does not remove his kippah, and is not expected to.) I began this post with Meir Soloveichik. There was actually another Soloveitchik who also had a great interest in things Christian. I refer to R. Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik. Here is a picture of him.

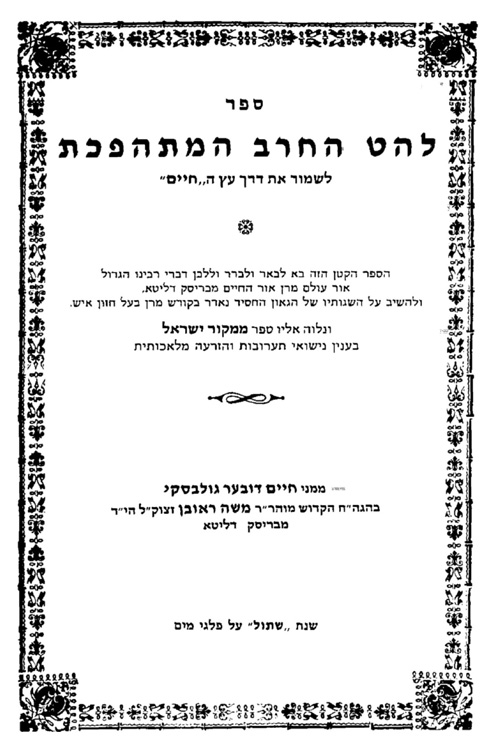

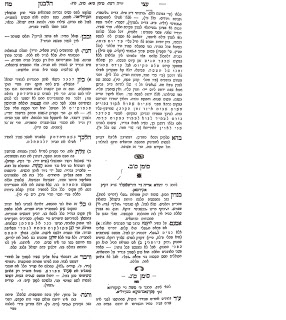

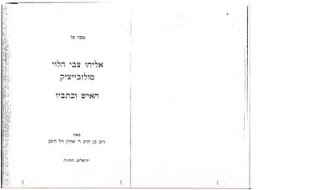

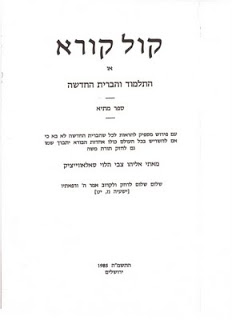

He was the grandson of R. Hayyim of Volozhin and the uncle of R. Joseph Baer Soloveitchik, the Beit Halevi. He is also the subject of a comprehensive monograph by Dov Hyman, who was a medical doctor trained in London and who lived in Manhattan. For some reason this book was kept fairly secret, with only fifty copies published and never sold in stores. Here is the title page of the book. Among Soloveitchik’s works is a volume entitled Kol Kore (Paris, 1875). Friedberg, Beit Eked Seforim, describes this book as “in opposition to the New Testament.” Yet Friedberg never looked carefully at the volume, for if he did he would have seen that rather than being in opposition to the New Testament, it is in favor of it. Yet it is not a missionary tract. Rather, Soloveitchik followed the approach of R. Jacob Emden (whom he cites in his introduction) that the New Testament is only directed towards Gentiles, and supports the Noahide Laws. However, it has nothing to say to Jews, whom it acknowledges are obligated to keep the Torah. In line with this conception, Soloveitchik felt comfortable in authoring a commentary on the book of Matthew, and that is what the Kol Kore is. Here are the title pages of the first edition as well as the 1985 reprint.

Among Soloveitchik’s works is a volume entitled Kol Kore (Paris, 1875). Friedberg, Beit Eked Seforim, describes this book as “in opposition to the New Testament.” Yet Friedberg never looked carefully at the volume, for if he did he would have seen that rather than being in opposition to the New Testament, it is in favor of it. Yet it is not a missionary tract. Rather, Soloveitchik followed the approach of R. Jacob Emden (whom he cites in his introduction) that the New Testament is only directed towards Gentiles, and supports the Noahide Laws. However, it has nothing to say to Jews, whom it acknowledges are obligated to keep the Torah. In line with this conception, Soloveitchik felt comfortable in authoring a commentary on the book of Matthew, and that is what the Kol Kore is. Here are the title pages of the first edition as well as the 1985 reprint.

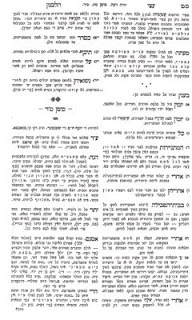

This is not the only rabbinic commentary on the book of Matthew. In 1900 R. Samuel Weintraub’s commentary on this Gospel was published (Milhemet Shmuel). Yet unlike Soloveitchik’s work, Weintraub’s commentary is devoted to exposing the Gospel’s faults.[29] Here are the two title pages of the book.

This is not the only rabbinic commentary on the book of Matthew. In 1900 R. Samuel Weintraub’s commentary on this Gospel was published (Milhemet Shmuel). Yet unlike Soloveitchik’s work, Weintraub’s commentary is devoted to exposing the Gospel’s faults.[29] Here are the two title pages of the book.

The book is an interesting polemic, which unlike most polemics is written in the form of a commentary. Yet there are times when the author goes too far. For example, he deals with Matthew 1:18, which states that Mary was impregnated by the Holy Spirit. Needless to say, he strongly attacks this notion. But he also has to make sense of Gen. 6:2, which states that “the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them as wives.” The problematic words are בני אלהים, as this might be taken to show that the Torah also shares the mythological conception of gods impregnating women. Weintraub writes: הוא כתרגום אונקלס בני רברביא, ואמרו בב”ר ר”ש בן יוחאי הי’ מקלל למי שמתרגם בני אלהיא, כי לא יתכן כלל שהמלאך יבוא אל האשה ויחמוד אותה, ורק העובדי אלילים היו מאמינים בשטותים הללו כמבואר בספרי מיטהאלאגיע ובס’ יוסיפון, תדע שהרי הכתוב מסיים עלה: וירא ד’ כי רבה רעת האדם בארץ, ולא כתיב כי רבה רעת בני אלהים בארץ, כי בני אלהים האמורים היו ג”כ בני אדם כתרגום אונקלס. ואם רצה השי”ת לברא את המשיח ברוח קדשו היה לו לבראו עפר מן האדמה מבלי אב ואם כמו שברא את אדם הראשון ואז היו כולם מודים בו ואין הקב”ה בא בטרוניא עם בריותיו. The only problem with Weintraub’s point is that in his zeal to attack the Christian belief, and by asserting that only pagans could believe in a nonsensical notion such that an angel could desire a woman, he has unknowingly also placed certain rabbinic texts into the category of not simply fools, but עובדי אלילים. Devarim Rabbah 11:10 describes how “two angels, Uzah and Azael, came down from near Thy divine Presence and coveted the daughters of the earth and they corrupted their way upon the earth until Thou didst suspend them between earth and heaven.” Similar passages are found in other rabbinic texts, in particular Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 22, which elaborates on how the angels desired and impregnated human women. This is part of the whole genre of “fallen angels” stories found in the ancient world. I personally have no doubt that passages such as these are foreign imports, mythological tales that somehow found their way into Jewish literature. Yet precisely because the “fallen angel” genre became part of Jewish tradition, even if one chooses to reject it I think it is going much too far to regard something that appears in traditional rabbinic sources as being idolatrous. The Sages could adopt non-Jewish notions when these related to science, history, and folklore – and even halakhah if Yaakov Elman is correct – but they would not adopt anything that smacked of idolatry. (I understand that this last statement can be challenged from a Maimonidean perspective. However, I don’t think Maimonides is correct, either historically or theologically, in the way he ties astrology to idolatry.)

The book is an interesting polemic, which unlike most polemics is written in the form of a commentary. Yet there are times when the author goes too far. For example, he deals with Matthew 1:18, which states that Mary was impregnated by the Holy Spirit. Needless to say, he strongly attacks this notion. But he also has to make sense of Gen. 6:2, which states that “the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them as wives.” The problematic words are בני אלהים, as this might be taken to show that the Torah also shares the mythological conception of gods impregnating women. Weintraub writes: הוא כתרגום אונקלס בני רברביא, ואמרו בב”ר ר”ש בן יוחאי הי’ מקלל למי שמתרגם בני אלהיא, כי לא יתכן כלל שהמלאך יבוא אל האשה ויחמוד אותה, ורק העובדי אלילים היו מאמינים בשטותים הללו כמבואר בספרי מיטהאלאגיע ובס’ יוסיפון, תדע שהרי הכתוב מסיים עלה: וירא ד’ כי רבה רעת האדם בארץ, ולא כתיב כי רבה רעת בני אלהים בארץ, כי בני אלהים האמורים היו ג”כ בני אדם כתרגום אונקלס. ואם רצה השי”ת לברא את המשיח ברוח קדשו היה לו לבראו עפר מן האדמה מבלי אב ואם כמו שברא את אדם הראשון ואז היו כולם מודים בו ואין הקב”ה בא בטרוניא עם בריותיו. The only problem with Weintraub’s point is that in his zeal to attack the Christian belief, and by asserting that only pagans could believe in a nonsensical notion such that an angel could desire a woman, he has unknowingly also placed certain rabbinic texts into the category of not simply fools, but עובדי אלילים. Devarim Rabbah 11:10 describes how “two angels, Uzah and Azael, came down from near Thy divine Presence and coveted the daughters of the earth and they corrupted their way upon the earth until Thou didst suspend them between earth and heaven.” Similar passages are found in other rabbinic texts, in particular Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 22, which elaborates on how the angels desired and impregnated human women. This is part of the whole genre of “fallen angels” stories found in the ancient world. I personally have no doubt that passages such as these are foreign imports, mythological tales that somehow found their way into Jewish literature. Yet precisely because the “fallen angel” genre became part of Jewish tradition, even if one chooses to reject it I think it is going much too far to regard something that appears in traditional rabbinic sources as being idolatrous. The Sages could adopt non-Jewish notions when these related to science, history, and folklore – and even halakhah if Yaakov Elman is correct – but they would not adopt anything that smacked of idolatry. (I understand that this last statement can be challenged from a Maimonidean perspective. However, I don’t think Maimonides is correct, either historically or theologically, in the way he ties astrology to idolatry.)

With regard to ‘fallen angels”, and the cross-cultural influence on Judaism, Rabbi Leo Jung’s volume on the topic was long the classic treatment.[30] He deals with all sorts of folklore in the aggadic literature, much which has its origin in non-Jewish sources.[31] While today, this sort of book would be excommunicated in certain circles, even years ago Jung was sensitive to the implications of what he was writing. He therefore included at the beginning of the book some pages about the authority of the aggadah. This is quite interesting, since one does not expect to find such a discussion in an academic work.[32] He notes that the purpose of Aggadah is not history, but to amuse, to cheer up, to let the people forget their present suffering by either leading them back to the glorious past or by painting in bright colors the fullness of times when there will be no enemy, no slander, no prejudice. There is no trace of a definite method, of any endeavor to weave these stories into a dogmatic texture, the Haggadah containing all that had occupied the popular mind, what they had heard in the beth hammidrash, or at a social gathering. Stories contradicting each other, theories incompatible with one another, are very frequent. They are recorded as the fruits of Israel’s genius. They have no authority, they form no part of Jewish religious belief. Nor may they be taken literally: it is always the idea, the lesson, and not the story, which is important. It is wrong to say that the Haggadah contains the doctrines of the Rabbis, or that only orthodox views have been admitted to the exclusion of all the rest (pp. 3-4).Jung continues by citing the classic sources in this regard, namely, R. Sherira Gaon, R. Samuel ha-Nagid, and of course, R. Abraham ben Maimonides. He also cites R. David Zvi Hoffmann, “recognized as the greatest rabbinical authority of our age” (p. 4), who in his introduction to his commentary to Leviticus states that there is no obligation to accept Aggadah. Jung concludes:It is very important to remember that there is no such thing as a systematic Jewish Theology. Even a system of fundamental points of creed did not grow up before the times of the Karaites and then was evolved through the necessity of defending Judaism. Maimonides endeavored to condense Judaism into thirteen principles of faith, but, as Crescas rightly contends, they are both too many and too few. The Haggadah, while preaching the beauty of holy life, does not give us law of belief and practice; the religious conduct of the Jew is regulated entirely by the Halakha (pp. 6-7).The status of Aggadah has been raised so much in recent centuries that people today are often unaware of the attitude towards Aggadah of some geonim and rishonim, in how they were prepared to reject aggadot that didn’t appeal to them. Thus, they will be surprised to read what Jung writes. For similar sentiments from another Orthodox leader, let me quote from Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz, in his Foreword to the Soncino Talmud (in words that today would land him in herem): We have dogmatical Haggadah, treating of God’s attributes and providence, creation, revelation, Messianic times, and the Hereafter. The historical Haggadah brings traditions and legends concerning the heroes and events in national or universal history, from Adam to Alexander of Macedon, Titus and Hadrian. It is legend pure and simple. Its aim is not so much to give the facts concerning the righteous and unrighteous makers of history, as the moral that may be pointed from the tales that adorn their honour or dishonour. That some of the folklore elements in the Haggadah, some of the customs depicted or obiter dicta reported, are repugnant to Western taste need not be denied. “The great fault to be found with those who wrote down such passages,” says Schechter, “is that they did not observe the wise rule of Dr. Johnson who said to Boswell on a certain occasion, ‘Let us get serious, for there comes a fool.’ And the fools unfortunately did come, in the shape of certain Jewish commentators [!] and Christian controversialists, who took as serious things which were only the expression of a momentary impulse, or represented the opinion of some isolated individual, or were meant simply as a piece of humorous by-play, calculated to enliven the interest of a languid audience.” In spite of the fact that the Haggadah contains parables of infinite beauty and enshrines sayings of eternal worth, it must be remembered that the Haggadah consists of mere individual utterances that possess no general and binding authority. to be continued . . .