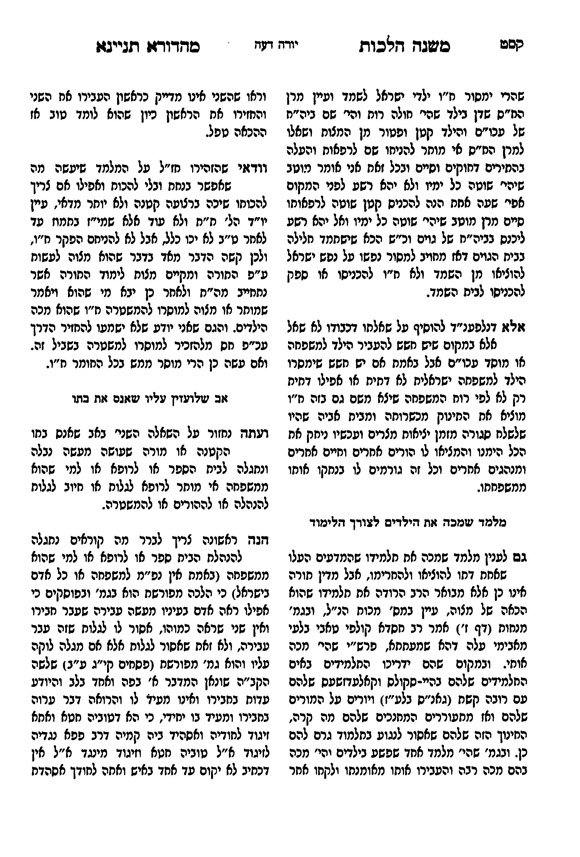

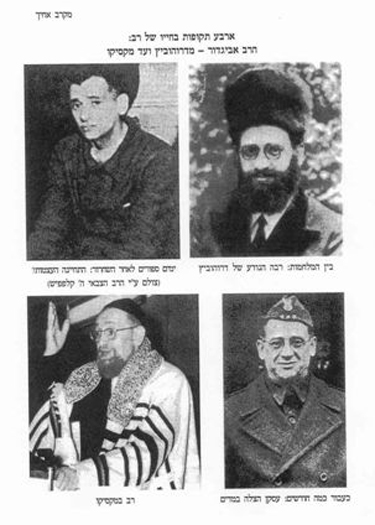

Comments on This and That, part 2

Originally, it is said, Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes were suppressed, for since they were held to be mere parables and not part of the Holy Writings [the religious authorities] arose and suppressed them. [And so they remained] until the men of Hezekiah came and interpreted them.

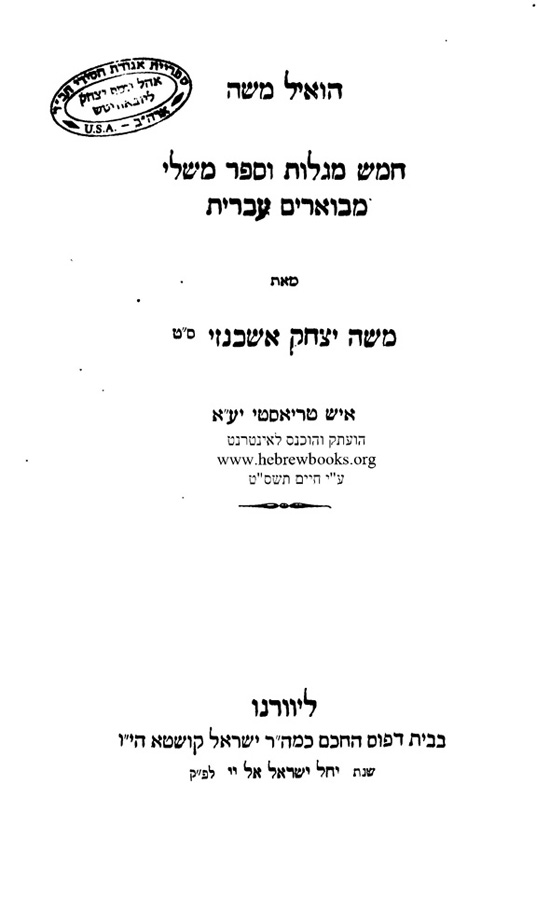

While Artscroll sees a literal interpretation of Song of Songs as blasphemous, Ashkenazi (together with Breuer and Barth) sees the book as teaching the values that make for a successful marriage. This viewpoint is also expressed in the introduction to the Soncino translation:

The main moral of the Book is that love, besides being the strongest emotion in the human heart, can also be the holiest. God has given the gift of love to sweeten the toil of the laborer, as in the case of Jacob to whom the fourteen years in which he toiled for Rachel appeared but a few days, for the love he had for her (Gen. xxix. 20). Love transfigures and hallows, but it’s a boon that requires zealously to be guarded and sheltered from abuse. This Book pictures love as a reward enjoyed only by the pure and simple, a joy not experienced by the pleasure-seeking monarch and the indolent ladies of the court. It is a joy reserved for the loyal and the constant, and is denied to the sensual and dissolute.

Ashkenazi concludes with these strong words:

גם אם נפרשהו ע”ד הפשט, נוכל ללמוד ממנו דברים נאותים. . . . רק אנשי חונף העושים מעשה זמרי ומבקשים שכר כפנחס יטילו בו דופי, בעוד שהם בשבתם על השולחן בבית חתן וכלה יוציאו מפיהם דברי נבלה המלבינים פני כל אדם ישר השמועה; והלואי ואולי היו משוררים שיר נחמד זה בסעודת חתנים. ויופי הקולות והנגינה ישמחו הלבבות ויגדילו חשק חתן וכלה זה לזה, ויגביהו לבות הבחורים והעלמות ברחשי הכבוד הראוים והנאותים להם.

I would assume that if a Modern Orthodox Machzor for Passover is ever published, that Hakham’s perspective will be the one to be included rather than what we find in Artscroll.

R. Zvi Yehuda has the same perspective, writing that the literal meaning has an independent existence, and “it too is raised to the level of holiness, not just on account of the nimshal, but on its own strength.”[4] He quotes Rashi who in his introduction to Song of Songs stresses that the allegory must be attached to the peshat of the verse:

ואף על פי שדברו הנביאים דבריהם בדוגמא, צריך ליישב הדוגמא על אופניה ועל סדרה.

The fact that the mashal needs to reflect reality is seen in another Rashi as well (not cited by Yehuda). Song of Songs 7:5 reads אפך כמגדל הלבנון. Rashi writes: “I cannot explain this [אפך] to mean a nose, either in reference to its simple meaning or in reference to its allegorical meaning, for what praise of beauty is there in a nose that is large and erect as a tower? I say therefore that אפך means a face.”

If the allegory is all that is important, then Rashi would not have a problem. He could translate אפך as nose, which is the literal translation,[5] and offer the allegorical explanation. Yet precisely because it is important that the peshat be coherent, Rashi is forced away from the literal meaning, for what man can praise his bride as being beautiful for having such a nose?[6]

One other interesting point that I learnt from Yehuda’s article is that the rishon, R. Avigdor Kohen Tzedek, gives the following strange explanation for why God’s name doesn’t appear in Song of Songs.[7]

ולא נכתב שם קודש בשיר השירים לפי שנאמר כל הספר בלשון חשק ואהבה ואינ’ דרך כבוד להזכיר השם ב”ה על דבר חשק.

ואחרי אלה ההערות אינני רואה שיסופק שום משכיל בדברי הספר לחשב בם שהם כפשוטם, ואלו היו כפשוטם לא היו חולי חולין בעולם כמותם, ולא היה נזק גדול לישראל כיום שניתן להם שיר השירים, כי פשוטו יעורר תאוה וביותר תאות המשגל אשר היא המגונה מכלם

שיר השירים, על כל בחינותיה ורבדי מובניה – ואף לפי פשוטה – היא “קודש קודשים”. האהבה האנושית המתוארת בה – מתרוממת לגובהי קדושה.

He concludes (p. 481) that it is a mistake to think that the Sages explained Song of Songs allegorically because they had a problem with its literal meaning. According to Yehuda, the opposite is the case, and it is precisely because the Sages valued the literal meaning of the book that they explained it allegorically. It is because they saw the human love described in the book as so exalted that they were prepared to also view the book as an allegory for heavenly love.

שכל הלשונות שבמשל הן עצמיים ובשרשם העליון ענינם נשגב למאד, אלא שהענינים הרמים אלה משתלשלים ויורדים מעולם לעולם עד שמגיעים אלינו מצטיירים לנו צורה זו הנאותה לפי מציאות האדם בעולם הזה.

With regard to Artscroll, everyone knows that the “translation” they provide of Song of Songs is allegorical. In the Passover Machzor that is all you get, but in their separate edition of Song of Songs they do provide the literal translation in the commentary, for those who wish to look at it. Artscroll’s approach vis-à-vis the Song of Songs has been the subject of harsh criticism in the Modern Orthodox world, especially from its intellectual elite. In fact, I think when people criticize Artscroll, this is one of the things that is high on the list of what annoys them.

Yet what about Israelis? We now have a situation where “the masses” can understand the Hebrew Bible since Hebrew is their vernacular. This is a completely new phenomenon. How are these masses to be protected from reading the text literally, for as we have seen, Artscroll tells us in the Pesach Machzor that “the literal meaning of the words is so far from their meaning that it is false”? In the Introduction to the Artscroll Shir ha-Shirim, p. lxiv, we are told that when the words שני שדיך, “your bosom” [Artscroll won’t use the word “breasts”] refer to Moses and Aaron, this is not

departing from the simple literal meaning of the phrase in the least. Song of Songs uses words in their ultimate connotations. Just as geshem, rain, means the power of stimulating growth, shodayim, the bosom, refers to the Heavenly power of nourishment. . . . They [Moses and Aaron], Israel’s sources of spiritual nourishment, are not implied allegorically or derived esoterically from the verse; the verse literally means them.

(Speaking of haredi circumlocutions, since the Agudah convention is in a few days I can’t resist mention of the following. A letter was sent out to attendees inviting them to a breakfast at which they will be addressed by a psychologist and and rabbi-lawyer. You can see the letter here. Notice that the letter speaks about how “the issue of child abuse has become a major topic in our society and children in our community have been and continue to be at risk.” Of course, child abuse is not the issue at all. We are not being confronted on an almost weekly basis with stories of children in our communities being beaten or anything like that. What we have is child sexual abuse, and yet the author of this letter can’t even bring himself to say the word “sexual.” It’s like we are all in grade school and this word is off-limits.)

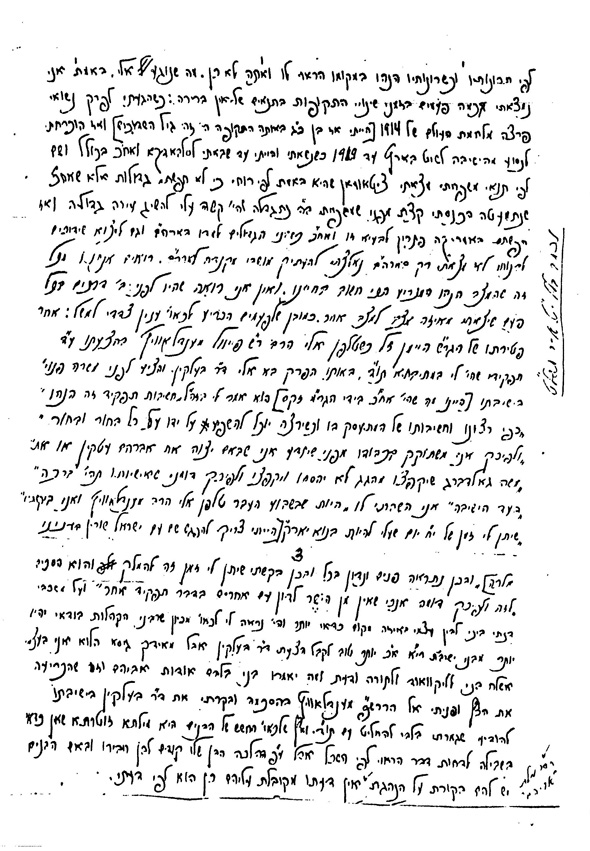

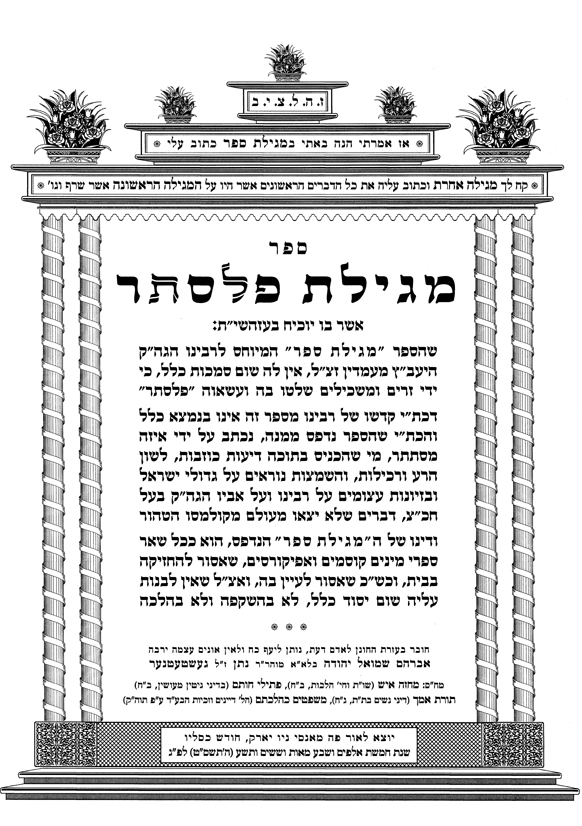

There was, in fact, one person who did refuse to change his mind, even after I presented him with the evidence. I refer to the late R. Meir Amsel, editor of Ha-Maor. Amsel is deserving of his own post, having edited Ha-Maor for over fifty years. If I were to ever write a history of Orthodox Jews in America, this journal would be an important source, together with its competitor, Ha-Pardes, because in these journals one finds most of the important issues that were part of the American Orthodox experience. Ha-Maor was the more extreme of the two journals, and all sorts of polemics were carried in its pages. But it would also contain all sorts of surprises, and Amsel’s viewpoints were not always predictable. Yet as I mentioned, he didn’t accept what I told him, and changing his mind even in the face of evidence to the contrary was not something he was prepared to do.

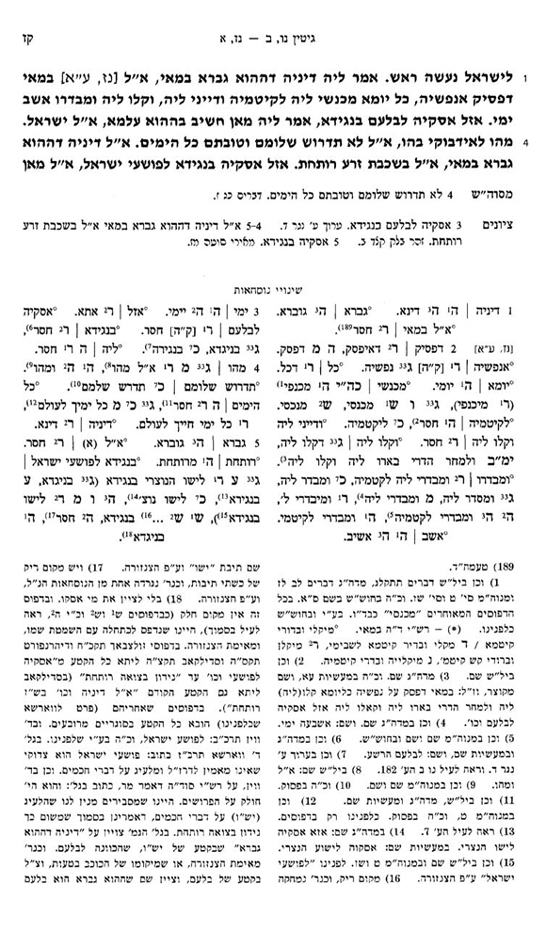

I sent him a second letter which he published, together with his response, in the March-April 1993 issue. Notice how he subtly mocks me at the beginning of this reply.

* * *

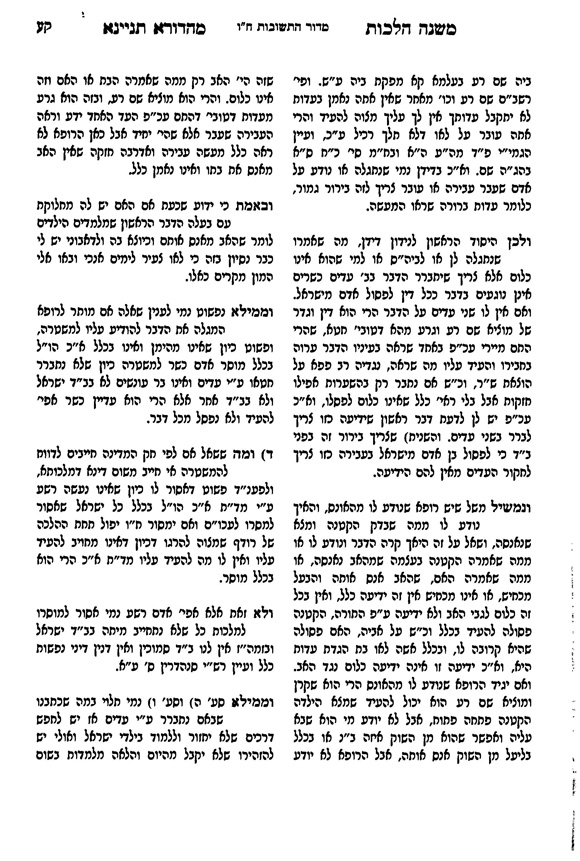

The custom on Rosh ha-Shanah is to sound additional shofar blasts towards the end of the morning prayers. Most sound these blasts after Musaf of Rosh ha-Shanah, while some sound thirty of them during the silent Amidah. There is no talmudic source for this practice. Why then do we do it? Here is how the Artscroll Machzor explains the matter, citing Eliyahu Kitov’s Sefer ha-Toda’ah as the source:

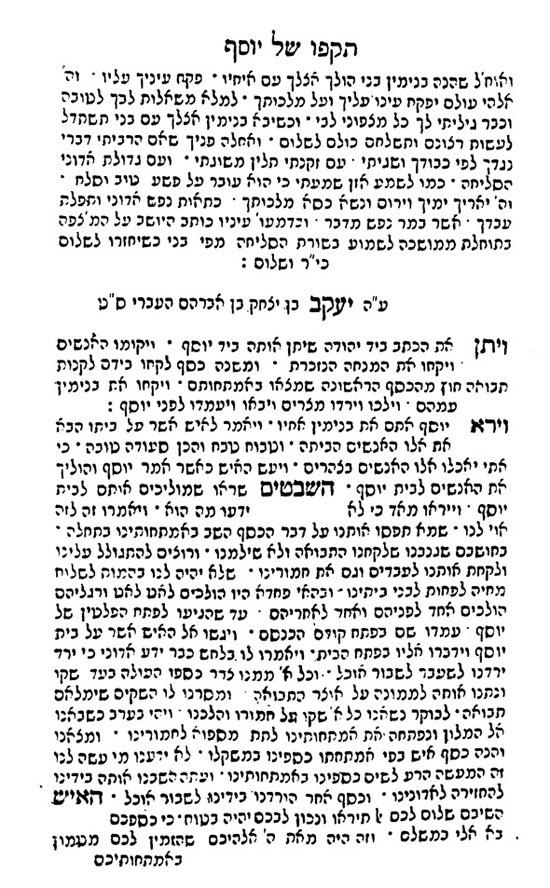

The source of this custom is the Scriptural narrative of the triumph of Deborah the Prophetess over Sisera, the Canaanite conqueror. In her song of gratitude for the victory, Deborah noted that Sisera’s mother whimpered as she worried over the fate of her dead son. Her friends comforted her that he had surely won a great victory and was apportioning spoils and captive women among his officers and troops (Judges 5:28-30). According to the Midrashic tradition she whimpered and groaned 101 times. Although one cannot help but feel sympathy for a worrying, grieving mother, one must be appalled at the cruelty of a mother who could be calmed by the assurance that her son was busy looting and persecuting innocent victims. The Jewish concept of mercy is diametrically opposed to such barbarism. By sounding the shofar one hundred times, we seek to nullify the forces of cruelty exemplified by Sisera and his mother, and bring God’s compassion upon us. Although she whimpered one time more than a hundred, we do not sound the shofar 101 times, because we, too, feel the pain of a mother who loses a child, even one as loathsome as Sisera.

והנה אם סיסרא פעתה ובכתה מאה בכיות, ואנו תוקעים מאה תקיעות ועוד אחד, כדי לבטל הקטרוגים הנמשכים מהבכיות שלה . . . וזהו “הן אתם מאין ופעלם מאפע.” “מאין” = 101 הן ה100 פעיות של אם סיסרא שבמאה ואחת תקיעות שלנו ה’ מכפר לנו, ומתקנים אנו את הפעיות [“אפע” נוט’ פעיות אם] של אם סיסרא.

When Abraham returned from Mount Moriah in peace, the anger of Samael [Satan] was kindled, for he saw that the desire of his heart to frustrate the offering of our father Abraham had not been realized. What did he do? He went and said to Sarah: “Hast thou not heard what has happened in this world?” She said to him: “No.” He said to her: “Thy husband, Abraham has taken thy son Isaac and slain him and offered him up as a burnt offering upon the altar.” She began to weep and to cry aloud three times corresponding to the three Tekiot, three howlings corresponding to the Teruot. and her soul fled, and she died.

In this text we have a connection made between the cries of Sarah and the blowing of the shofar. Here it states that she cried three times corresponding to the Tekiah and three times corresponding to Teruah. (What we call Shevarim is one possibility for how the Teruah should be sounded.) Alternate versions have Sarah crying aloud six times or ninety times.

The change was obviously made in response to criticism. Yet they should have stuck with the original version, since what appears in the “corrected” edition is mistaken. I assume that Artscroll knows it is mistaken, but leaves it in anyway so as not to antagonize its critics.

In the Machzor for Sukkot, p. 132, in discussing the different practices when it comes to wearing tefillin on hol ha-moed, it states: “It is not proper for a congregation to follow contradictory customs. Thus, if one whose custom is not to wear tefillin during Chol haMoed prays with a tefillin-wearing minyan, he should don tefillin without a blessing. Conversely, if one whose custom is to wear tefillin prays with a non-tefillin-wearing minyan, he should not wear his tefillin while praying but may don them at home before going to the synagogue.” The source for this ruling is the Mishnah Berurah. Yet with the exception of hasidic synagogues, where I presume everyone does the same thing, this ruling is no longer applicable. In all the synagogues I have ever been in, both Modern Orthodox and non-hasidic haredi, there is no one minhag and everyone does what his family practice is. In other words, the minhag today is for everyone to follow his own personal minhag, and shuls do not have a “custom” in this regard.

Also in the Sukkot Machzor, p. 957 (as well as in the other Machzors), it writes as follows: “It is virtually a universal custom that those whose parents are still living leave the synagogue during Yizkor. This is done to avoid the ‘evil eye,’ i.e., the resentment that might be felt by those without parents toward those whose parents are still living.” Can one conclude from this that Artscroll has a Maimonidean approach to the concept of the “evil eye”?

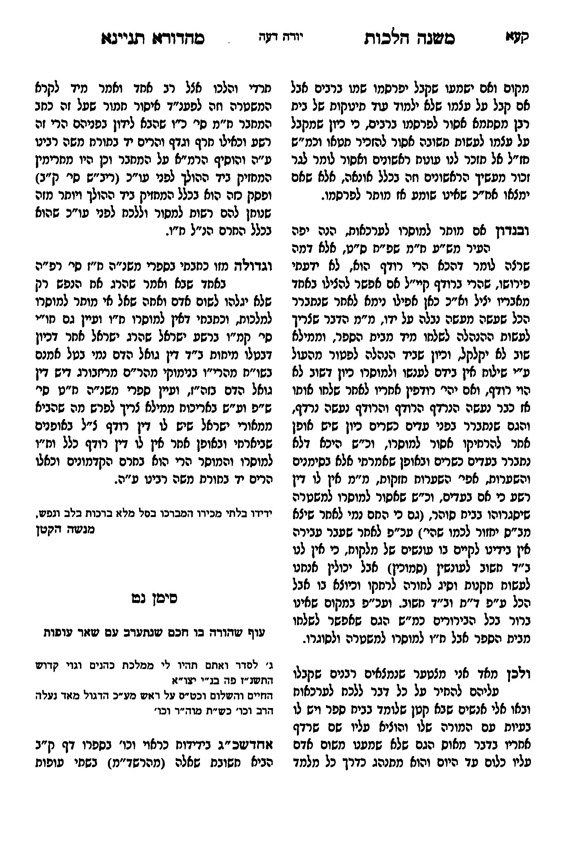

In past posts I have offered a quiz and given out prizes to the ones who answered the questions. People have wondered why I stopped doing this. The answer is simple: I didn’t have anything to give out. But now I have a few items so I can do some more quizzes. For the winner of this one I can give a CD of the music of R. Baruch Myers, rav of Bratislava. Rabbi Myers is a trained classical musician and his music is very different from what you think of when you think hasidic music. Unlike in the past, I will not give the prize to the one who answers the question first. This is unfair as due to the different time zones, some people won’t see the question until it has already been answered. I will give people a couple days and if more than one has answered correctly, I will randomly choose a winner. You will also have to answer two questions, in different genres. Yet even if you only know the answer to one, send it in, for if no one gets both answers, I will give it to a person who got one correct. Send answers to shapirom2 at scranton.edu

Question 2: There is a rabbinic phrase that today is used to praise a Torah scholar, but in talmudic days was used in a negative fashion (at least according to Rashi). What am I referring to?

Some people have asked me if I am leading a Jewish history trip to Europe this summer. Actually, I am leading two trips, one to Italy and the other to Central Europe. (The latter is a repeat of the sold-out trip from last summer). Both trips are sponsored by Torah in Motion and details will be available soon.

* * * *

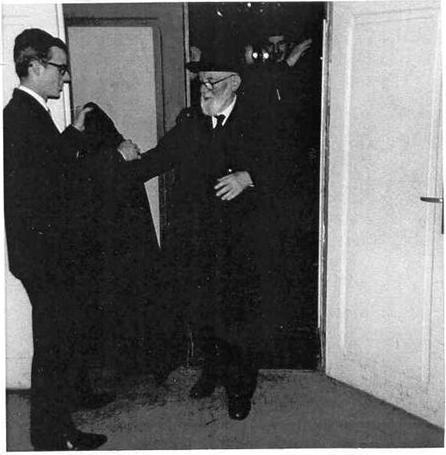

Here is something I think readers will enjoy. It is a picture from Prof. Isadore (Yitzchak) Twersky’s wedding. I thank R. Aharon Rakefet for sharing the picture. According to R. Rakefet, the man second to the left, whose face is obscured by an unknown rabbi, is R. Zev Gold. (R. Rakefet claims that the hair gives it away.) Beginning with Gold, we find Dean Samuel Sar, Isadore Twersky (standing) R. Dovid Lifshitz, R. Eliezer Silver, the Rav, R. Chaim Heller, R. Meshullam Zusia Twersky, Tolner Rebbe of Boston, R. Moshe Zvi Twersky, Tolner Rebbe of Philadelphia.

[2] This identification has recently been advocated by Christopher W. Mitchell in his massive work, The Song of Songs (St. Louis, 2003), pp. 130ff.

[3] Medieval commentators, notably Ibn Ezra, put a great deal of effort into explaining the peshat. See also the medieval commentary on Song of Songs written by R. Joseph Ibn Aknin, entitled Hitgalut ha-Sodot ve-Hofa’at ha-Meorot (Jerusalem, 1964). Ibn Aknin provides a three part commentary, with one section focused on peshat, and the other two on derash and sod. From more recent times, see R. Samuel Naftali Hirsch Epstein, Imrei Shefer (Vilna, 1873), and R. Eliyahu Halfon Shir ha-Shirim im Perush Ateret Shlomo (Nof Ayalon, 2003).

[4] “Shir ha-Shirim” Kedushatah shel ha-Megilah u-Farshanutah,” Sinai 100 (1987), p. 475.

[5] Soncino explains: “The comparison is between the well-proportioned nose and the beautiful projecting tower.”

[6] This point was made by R. Isaac Jacob Reines. See R. Judah Leib Maimon, ed., Sefer Rashi (Jerusalem, 1956), vol. 2, pp. 12-13. See also Rashi to Song of Songs 1:2 “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth.” Rashi comments: “In some places they kiss on the back of the hand or on the shoulder, but I desire and wish that he behave toward me as he behaved toward me originally, like a bridegroom with a bride, mouth to mouth.” Artscroll does not mention this Rashi. The Vilna Gaon has an interesting comment on this verse. He notes the plural “kisses,” and explains: כמו שנושק הבעל לחשוקתו א’ על מה שמתחברת עמו והב’ על שאינה מתחברת באחר

[7] Perush Shir ha-Shirim (Jerusalem, 1971), p. 11.

[8] See also Ibn Ezra’s introduction to Song of Songs: וחלילה חלילה להיות שיר השירים בדברי חשק Despite saying this, he still feels it is important to explain the peshat.

[9] See also Rav Pealim, vol. 4, Sod Yesharim no. 11, where R. Joseph Hayyim explains why God’s name does not appear in the Song of Songs.

[10] Since we are speaking of love, I should also mention Elhanan Reiner’s provocative claim, put forward in very stylistic Hebrew, that R. Yair Haim Bachrach’s responsum, Havot Yair, no. 60, is not a real case, but simply a fictional love story that Bacharach inserted into his responsa. See here. For Raphael Binyamin Posen’s response see here, and Reiner responds to Posen here.

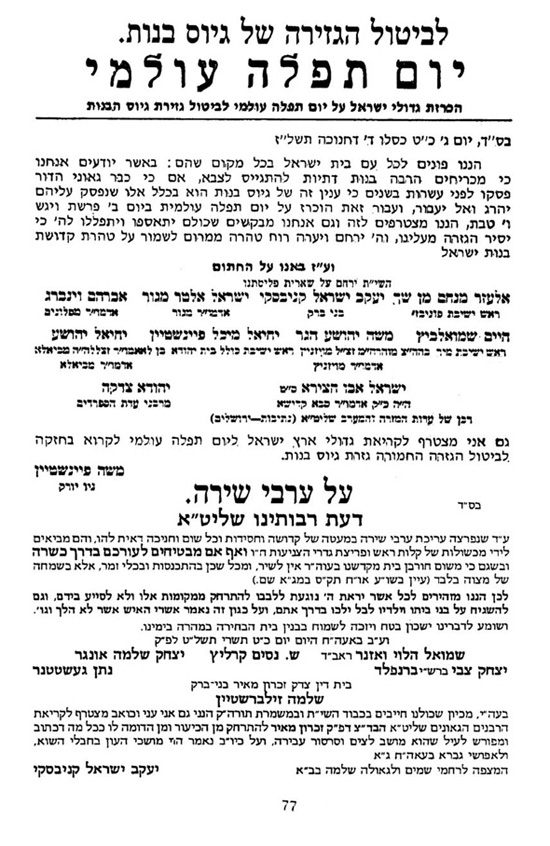

[11] Incidentally, the opposition of haredi gedolim to these concerts is often portrayed as if the only issue is tzeniut, and therefore, when men and women sit separately there should be no problem. This is a complete distortion of the issue, for even without tzeniut concerns, the main reason for the opposition, and I know this will be hard for American haredim to stomach, is that the Israeli haredi gedolim are opposed to all musical entertainment, and “fun” in general, when not connected to simchah shel mitzvah, such as Purim, a wedding, etc. Concerts are doubly problematic since these gedolim believe that is forbidden to listen to live music when not connected to a seudat mitzvah. Here is one proclamation that makes this clear (from Hashkafatenu [Bnei Brak, 1985], p. 77).

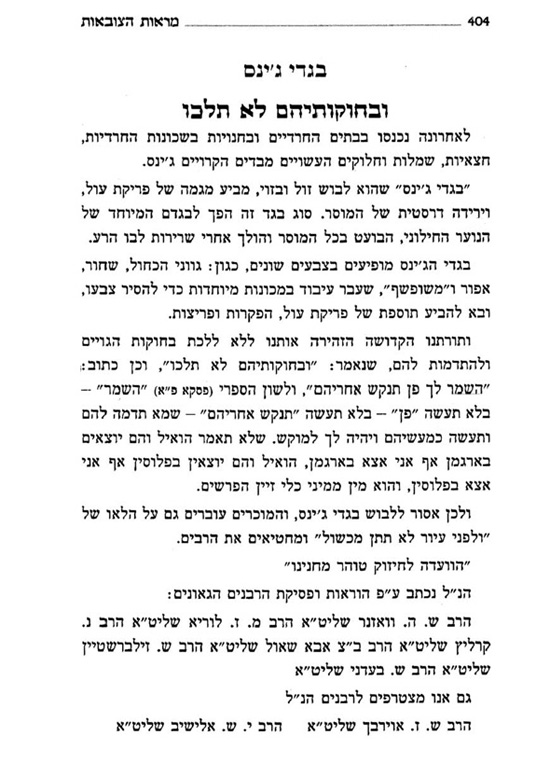

In R. Yaakov Yisrael Lugasi’s Mar’ot ha-Tzovaot (Jerusalem, 2009), p. 401, he states flatly: “The entire concept of entertainment is pasul. This is a condition of moshav leitzim and throwing off the yoke, and is the culture of the non-Jews and the secularists.” Interestingly, a few pages after this, Lugasi prints the herem against wearing jeans skirts. For those who never saw it, here it is.

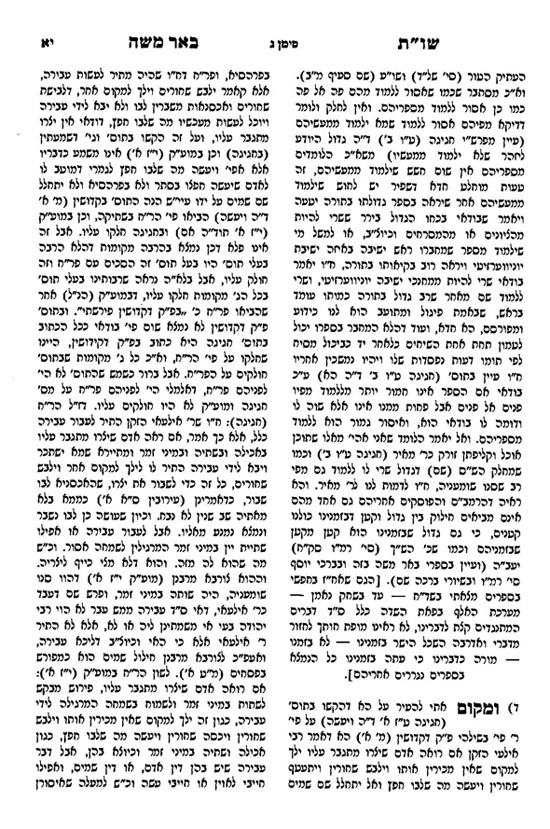

See also p. 404 for the following incredible statement: “Rav Ahron told his son that it is not right to print his brother’s דרשה of יוסף ואחיו about the Mizrachi because his brother regretted saying this דרשה ” This is perhaps the most important derashah the Rav ever delivered and is a basic text of study for religious Zionists. It explains how the Rav could break from his family tradition and become a Zionist. It is also the derashah that R. Shakh attacked, saying that it contained דברים שאסור לשומען וכש”כ להפיצן ברבים (Mikhtavim u-Ma’amarim, vol. 4, no. 320). What are we to make of R. Ahron stating that the Rav regretted this derashah?

Among other passages that caught my eye, see e.g., p. 6, where R. Ahron tells a bubba maisah about a rabbi in Auschwitz who killed some twenty Nazis with a chair. On p. 327 R. Ahron claims that Bible Criticism “paved the road for the Nazi ideology.” On this page he also states that Catholics do not support Bible Criticism. This is incorrect. The Catholic Church accepts Bible Criticism and does not see this as harming the holiness of the Bible. In fact, there are only two religious groups that do not accept the academic approach to the Bible, namely, Christian fundamentalists and (most) Orthodox Jews. (In a future post I will explain why I use the word “most”.

Why do I say that this is an unfortunate publication? Because there is a way to write and a way not to write, and someone who is very upset about how his father was treated is not the best person to review important incidents in his life. I can’t see how anyone could believe that the book brings honor to R. Ahron. I am impressed, however, that despite the harshly polemical tone, the author included documents directed against R. Ahron, as this helps with the historical record.

When publishing the letter of the other faculty members of Hebrew Theological College stating that they do not want R. Ahron in a leadership position, the author would have been wise to explain the different perspectives of the protaganists, rather than heaping abuse on them. The same is true when it comes to how he describes the haredim. There is no question that many of his complaints are justified. This is especially the case when he deals with the support given by the haredi gedolim to Elior Chen, which makes everything else pale in comparison. Yet despite this, the language Soloveichik uses in is really over the top.

I also can’t imagine that the family of the Rav will be happy to see how he too makes appearances in the book. Is it really appropriate to quote the Rav’s harsh comment against a certain Agudah leader? And I have a more fundamental question with regard to this last example. When two people agree to take their dispute to a beit din, not a government beit din but a private beit din, don’t they have an expectation of confidentiality? This is especially the case when one of the disputants is still alive. What gives the author the right to reveal the content of a private dispute brought before a private beit din, even if one of the participants did act in a disgraceful manner?

2. R. Ahron told me, halakhah le-ma’aseh, that if you have food in the oven when Shabbat starts, that this food can be returned to the oven on Shabbat morning in order to heat it up. I have heard that the Rav gave the same pesak to NCSY, but I have not confirmed this.

[13] See Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 596:1; Sefer Zikaron Divrei Shelom Hakhamim (Jerusalem, 2003), p. 264.

[14] Otzar ha-Hayyim, Tevet 5695, pp. 87-88.

[15] Ner Maaravi 2 (1925), pp. 227-228; Divrei Menahem, vol. 4, no. 13.