The Vilna Gaon, Part 1 How Modern Was He?

Eliyahu Stern, The Genius: Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism (New Haven, 2013)

Eliyahu Stern has set for himself a daunting task and argues his case with conviction. He intends to correct a widespread assumption shared not only by the general public, but by the scholarly community as well. According to this narrative, the Vilna Gaon (hereafter the Gaon) should not be seen as a traditionalist defender of the past, but actually a modern Jew and one who helped usher in the modern era in Jewish history. In Stern’s words, “I [have] come to believe that [Jacob] Katz’s and [Michael K.] Silber’s notion of tradition and traditionalism fails to explain the experience of the overwhelming majority of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century eastern European Jews who did not spend their days either combating the Western European secular pursuit of science, philosophy and mathematics or holding onto the same political and social structures of their sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ancestors. Katz and Silber might have been right about [R. Moses] Sofer. . . . But figures such as the Gaon of Vilna or Hayyim of Volozhin (the Gaon’s student and Sofer’s contemporary), who did not express hostility toward modernity, elude their grasp” (p. 7).

This is quite a claim, and it would be a major revision of the historical picture if Stern could prove the point. Stern also argues that the Gaon’s notes to the sixteenth-century legal code Shulhan Arukh were influential in Jews moving away from a “code-based learning culture supported by the kehilah” (p. 11).[1]

By focusing on Talmud study for its own sake rather than for the sake of determining the halakhah, a paradigm shift occurred in which commentary replaced code. This occurred at the very time that the yeshiva took the place of the kehilah, as seen in the establishment of the Volozhin yeshiva by the Gaon’s disciple, R. Hayyim. Thus, the hierarchy of religious authority was restructured, which leads to what Stern refers to as “religious privatization” (p. 11). As he sees it, “The Volozhin yeshiva was founded not in opposition to the cultural and intellectual upheavals of the nineteenth century. It was itself built on the most modern of assumptions, the separation of public and private spheres” (p. 141). Stern even makes the bold claim that in certain respects the Gaon was more modern than Mendelssohn, arguing that “it was the Gaon’s hermeneutic idealism that called into question the canons of rabbinic authority, while Mendelssohn tirelessly defended the historical legitimacy of the rabbinic tradition to German-speaking audiences” (p. 64). In seeking to turn the Gaon into a more modern Jew, one who is not, as standard scholarship assumes, an opponent of philosophy, Stern even argues that the Gaon did not believe in “demons, magic, [and] charms” (p. 129).[2]

After mentioning that the Gaon is embodied in the Jewish residents of Tel Aviv and New York, who live as though they are majorities, Stern concludes his book with this striking assertion: “From the birth of the State of Israel, to the Jews’ involvement in radical anti-statist modern political movements, to the creation of a robust vibrant Jewish life in the United States, Jewish modernity derives much of its intellectual dynamism, social confidence, and political assertiveness from an astonishing source: the brilliant writings and untamed personality of Elijah ben Solomon” (p. 171).

As with all revisionist theses there is bound to be reluctance to accept a new paradigm. The successful revisionist thesis is the one able to withstand the initial skepticism. Does Stern’s thesis fall into this category? Despite his enthusiastic and tempting arguments, I am not convinced. Reading the book, I could not help wonder if, for example, drawing contrasts with the thought of Leibniz offers any real insight into the thought of the Gaon. We know that the Gaon was fearless in emending rabbinic texts, but for Stern, “Elijah’s emendation project addresses the charge that Leibnizian idealism leaves no room for the possibility of progress, redemption, and critique. . . . Elijah embroidered the theological concept of evil around the idea of textual error” (p. 61). Isn’t this reading too much into what the Gaon had in mind? Why does the approach of the Gaon have to be given such theological weight that Stern can conclude that “emendation is the path toward redemption and a restored original harmony” (p. 62)?[3]

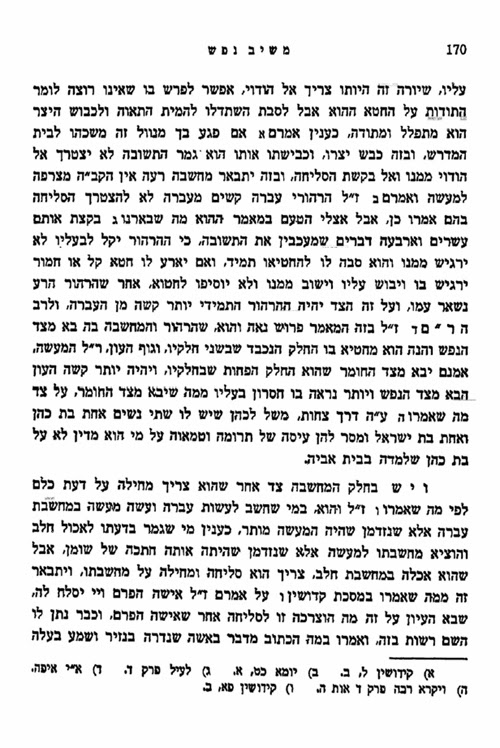

In another example of his revisionist approach, Stern argues that the Gaon did not oppose philosophy. Rather, “Elijah’s problem with Maimonides revolves around issues of linguistics, interpretation, and hermeneutics and not whether it is permissible to read secular philosophy” (p. 130). As noted already, Stern also assumes that the Gaon did not really believe in “demons, magic, charms and other irrational objects” (p. 129). There is no question in my mind that Stern is in error here. Because the Gaon was a traditional Jew, whose approach to the classical rabbinic texts was not influenced by rationalist philosophy, this is precisely why he believed in demons, magic, and charms. The only reason to reject these things, as did Maimonides, is because one is influenced by rationalist thought.

I see no evidence that the Gaon was influenced in any substantial way by such knowledge, and his occasional use of Aristotelian terminology does not by itself indicate real influence. Furthermore, everything in his writings leads one to believe that when it came to the occult his mental universe was no different than the great rabbis of his time and subsequent to him, for whom demons did indeed exist. In his famous attack on Maimonides, found in his comment to Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 179:13, he specifically mentioned the efficacy of magic, and contrary to Stern this is to be taken literally.[4]

In fact, a few notes later, 179:26-28, which are not mentioned by Stern, the Gaon again wrote about demons, mentioned that one is permitted to consult with them if it is not the Sabbath, and cited talmudic and midrashic texts that show humans interacting with demons.[5] The Gaon’s position in this matter does not need to be explained. Pretty much every traditional Jew in his day believed in demons, and he did as well. It is Maimonides’ opinion that is not traditional.

Stern leaves it as an open question whether the Vilna Gaon called philosophy “accursed” (p. 245). This is obviously an important issue, since if Stern is correct that the Gaon was not really opposed to philosophy, one would not expect him to use the word “accursed.” Yet there is no doubt that the Gaon did indeed use this word. It appears in the first printing of the Gaon’s commentary to the Shulhan Arukh, and its authenticity was attested to by R. Samuel Luria who examined that actual manuscript. Only later was the word removed by the publisher. Contrary to what Stern states, Samuel Joseph Fuenn, Matisyahu Strashun, and Hillel-Noah Maggid Steinschneider do not claim that later editors put in this phrase. The one to make this assertion was R. Zvi Hirsch Katzenellenbogen, and he was hardly a neutral observer.[6]

Several other issues emerge in the book. Stern quotes Aliyot Eliyahu as stating that before the age of thirteen the Gaon was “studying books on engineering for half an hour a day” (p. 38). I am not sure why Stern mentions anything about “thirteen,” as the text is explicit that he was around eight years old. Furthermore, the text says nothing about “engineering.” Rather, it states that the Gaon studied astronomy (tekhunah).

Stern writes that the Gaon “rejected outright” the Shulhan Arukh (p. 60). This is a strange statement being that the Gaon wrote a commentary on the Shulhan Arukh. Furthermore, this commentary was designed to show the earlier rabbinic sources upon which the Shulhan Arukh‘s laws were based. It is true that there are many times when the Gaon disagreed with the Shulhan Arukh. However, what is significant with the Gaon is precisely that he accepted the Shulhan Arukh. He had the stature to reject it had he chosen, and to write his own code, yet he did the exact opposite. By attaching his notes to the Shulhan Arukh he was affirming the work. He personally did not need the Shulhan Arukh and would decide halakhah from the Talmud and rishonim. But when the Shulhan Arukh decided the halakhah correctly, he was content to show the sources for the law, meaning that the work had value and that is why he affirmed it.[7]

Contrary to Stern (pp. 77-78), there is no evidence that the Gaon was influenced by Elijah Levita and the Gaon never mentioned him. When the Gaon wrote that the Masorah disagreed with the Talmud, he was referring to how to spell certain words, and this formulation comes from the Tosafists. He was not in any way identifying with Levita’s notion that the Hebrew vowels originated in post-talmudic times, and was certainly not addressing “the veracity of the cantillations of the Bible” (p. 78). When the Gaon’s son cited Levita, he was also not referring to his view of the vowels, only of the spelling of words.

I do not know what Stern means by “following Nachmanides, the Gaon argues that the book of Deuteronomy was written later than the other four books of the Bible” (p. 80). Quite apart from Nahmanides, this position is found in Gittin 60a, where one view is that the Torah was given “scroll by scroll.” Also on p. 80, Stern states that “the Gaon, in contrast, builds on the historical position laid down by Ibn Ezra that the last verses, though inspired by Moses, were actually ‘arranged’ by Joshua.” This has nothing to do with Ibn Ezra as the Talmud already contains the view that the last verses were written by Joshua (saying nothing about being “inspired” by Moses. [Ibn Ezra also says nothing about the last verses being “inspired” by Moses])

On page 133, Stern quotes a passage from the introduction to R. Judah Epstein’s Minhat Yehudah (Warsaw, 1877) where he writes of “thousands who came to study and the miracle it would take for one to emerge with any teaching ability.” In the Hebrew the final words are “yatza le-hora’ah.” This has nothing to do with teaching but refers to the ability to decide halakhic questions. The expression originates in Kohelet Rabbah 7:49.

Finally, he writes that “when the Volozhin yeshiva opened its doors in 1802, it was the first time that young men from all economic and social backgrounds were afforded the opportunity to study” (p. 150, see also p. 162). I know of no evidence to support this assertion. Both before the Volozhin yeshiva’s opening and after, opportunities for study were limited to those who could afford to support a child away from home, and give up the income he would bring in for the family.

Even though I am not convinced by Stern’s thesis, there is no doubt that this book is filled with learning and insight and has understandably created a good deal of excitement. To appreciate Stern’s efforts and ingenuity, one must read very carefully, and this reading will be rewarded in many ways.

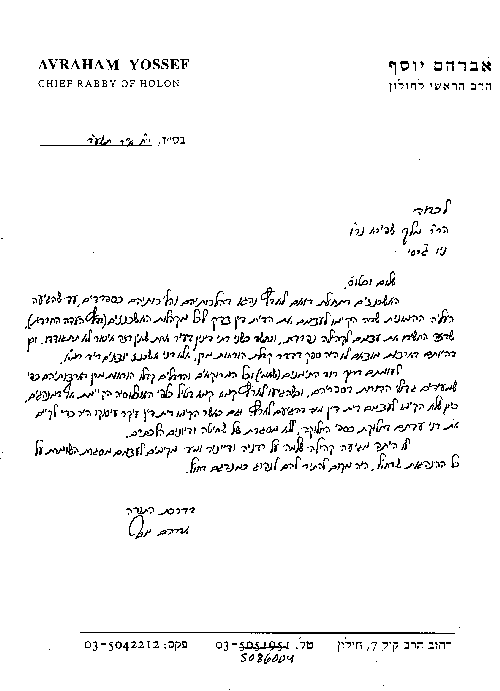

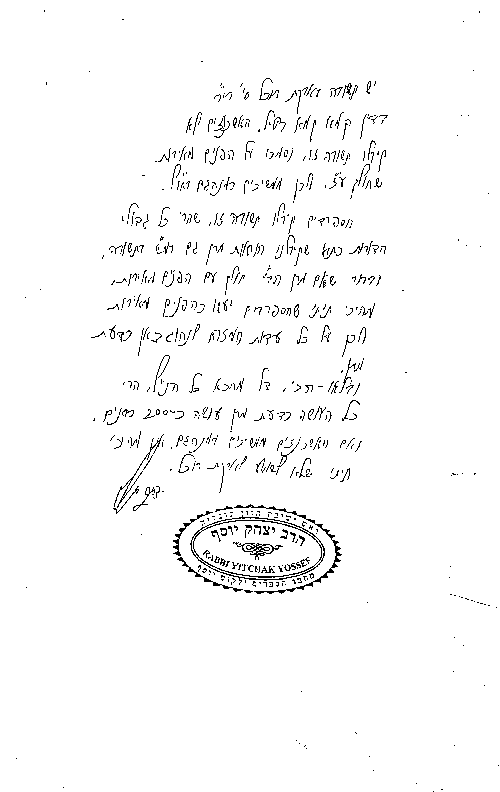

The review you have just read (with the exception of notes 1-5, 7, and one sentence in brackets) appeared on the H-Judaic listserv on July 19, 2013. In the review I was limited in terms of space and I also could not use Hebrew. So let me now add some additional points and corrections that could not be included in the original. Before doing so I want to stress that I enjoyed Stern’s book a great deal, and I also learnt much from it. The Gaon’s scholarship is so wide-ranging that anyone who attempts such a daunting task as to write on him must be commended.[8]

Stern should also feel gratified that so many people have chosen to use their precious time to write about his book, even if they disagree with him.

Stern’s first chapter, which puts the Gaon and Vilna in historical perspective, was particularly interesting to me. How many people, for instance, are aware of the following (p. 70): “The roughly 5,500 Jews in and around Vilna (Wojewoda) made up nearly 30 percent of the population, and the 3,500 to 4,000 Jews living within Vilna proper formed an overwhelming majority of the local population.”

I strongly recommend that people read the book, if only to see how the talented author attempts to create a completely new perspective on the Gaon. Almost every page of Stern’s book raises issues that I can comment on, and I could easily have written a hundred page post. I agree with much in the book, and can cite sources in support of a number of points Stern makes. Yet this does not change the fact that I was not convinced by his major arguments. Rather than cite all the things I agree with, let me offer some more comments correcting errors, or offering different interpretations, as well as some tangential observations.

P. 14. Stern tells us that the Gaon’s mother was from Slutzk, and on p. 181 he cites a source that supposedly claims that the Gaon was also born in Slutzk. Yet this is incorrect. The town referred to is not Slutzk but סעלץ. This is the shtetl Selets (or Selcz) around 150 kilometers south-east of Brisk.[9]

This information is also found in the

Encyclopaedia Judaica entry on the Gaon. There is another Selets in Belorussia, some eight hundred kilometers away,[10] but this is not the town associated with the Gaon. There is no actual proof that the Gaon was born in Selets, but that was the tradition of the town.[11]

P. 15. Stern records how the Gaon wanted to study medicine but was discouraged by his father who wanted his son to devote himself to Torah study. I don’t know if this has any relationship to the Gaon’s unusual (but not unique) view in opposition to using doctors as opposed to turning to God. According to one report, the Gaon only had this view when it came to internal medical problems, but not external ones (e.g., a burn).[12]

P. 17. Stern mentions the report by R. Samuel Luria that the Gaon travelled throughout Europe to find rabbinic manuscripts. Among the legends of these travels is one recorded in the name of R. Joseph Hayyim Sonnenfeld, quoting R. Joshua Leib Diskin, that when the Gaon visited the Munich library and saw the famous manuscript of the Talmud, he said that he would give all the money in the world in order to put it in genizah, because this Talmud was only R. Ashi’s first version (and thus of no authority). This story appears in Menahem Mendel Gerlitz’s Mara de-Ar’a Yisrael (Jerusalem, 1969), vol. 1, p. 57 n. 49. I can’t say whether or not R. Sonnenfeld ever made this comment (and Gerlitz’s book in general is quite unreliable). What I can say is that the story never happened as described for the simple reason that the manuscript only arrived in Munich in 1806, as noted by R. Raphael Rabbinovicz in the introduction to Dikdukei Soferim, vol. 1, p. 35.[13]

P. 44. “He [the Gaon] and his students reinterpreted a strand of kabbalah developed by Abraham Abulafia. . . . Elijah’s circle borrowed heavily from his ideas regarding the mathematical underpinnings of the world.” Unfortunately, this influence is never sufficiently explained and there is confusion about an important text. Thus, Stern writes:

As Menachem Mendel of Shklov wrote, “The word cheshbon [calculus] comes from the word machshava [thought] and this [calculus] is the first form that emerges from the essence of thought.”[14]

To begin with, I don’t know why cheshbon should be translated as “calculus.” I assume it means mathematics.[15] But that is a minor point, as the general meaning of the passage is clear and R. Menahem Mendel of Shklov tells us that this approach was shared by the Gaon. The more important point, however, is that the sentence quoted as having been stated by R. Menahem Mendel was not stated by him at all. R. Menahem Mendel tells us explicitly that the sentence comes from an early book, one that predates R. Isaac Luria. What we learn from Moshe Idel is that this is actually a quotation from Abulafia.[16] Yet this information does not appear in Stern’s book, even though it would have strengthened his case.

Stern also states: “Elijah’s son Avraham approvingly cites the much-maligned Abulafia, and bestows the honorific “z”l” (the Hebrew acronym for “may his memory be blessed”) on the controversial medieval thinker.”

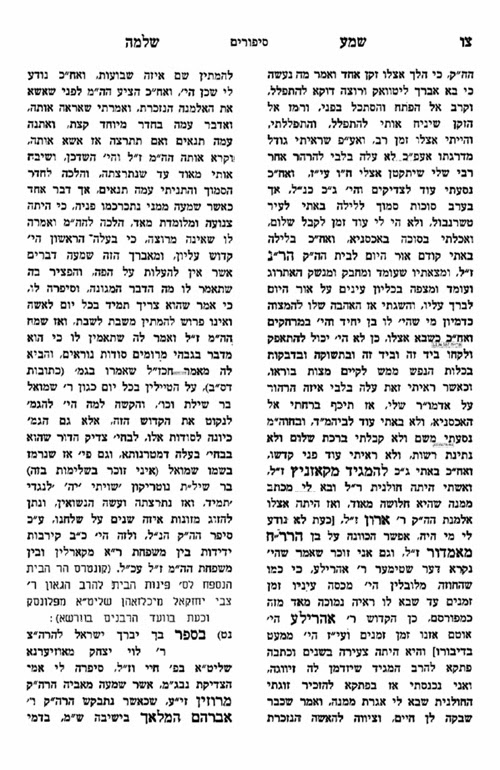

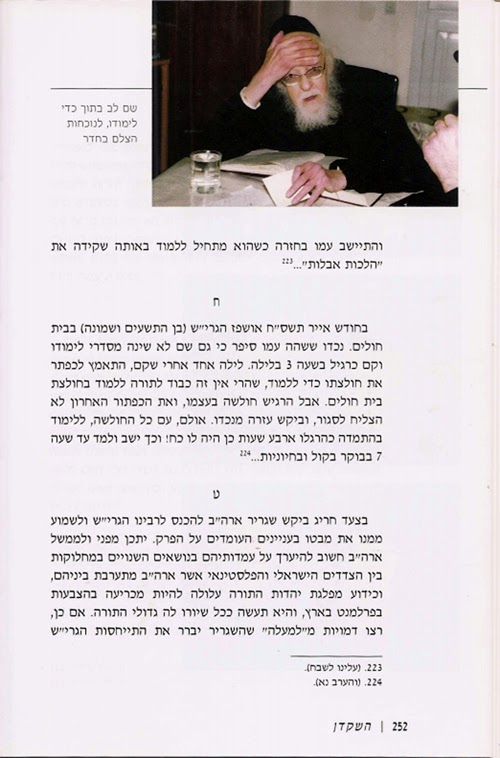

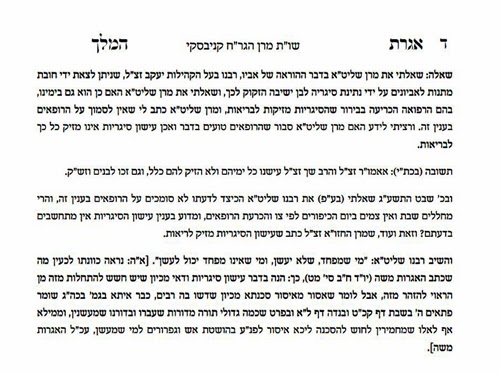

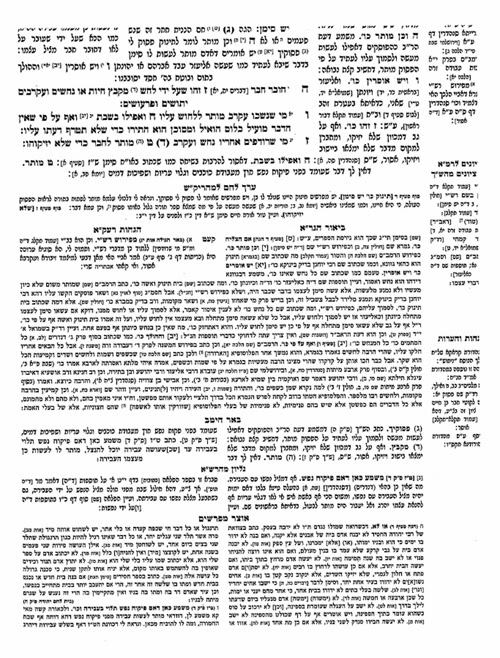

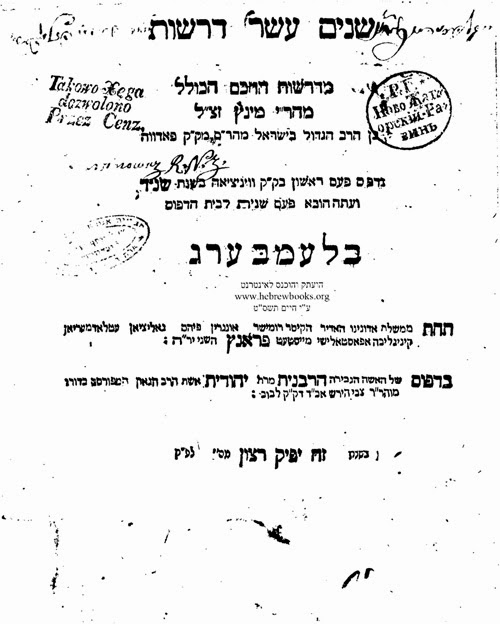

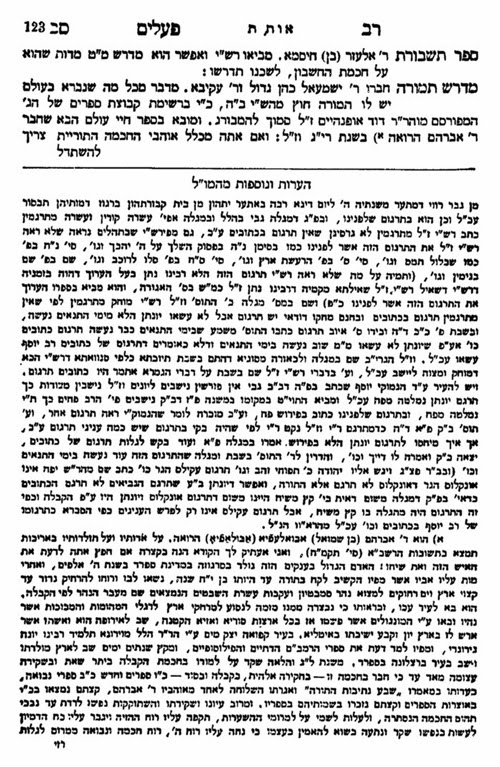

Here is the page in R. Avraham’s

Rav Pealim.

Unfortunately, Stern must have read too quickly and instead of וז”ל [= וזה לשונו] he read the abbreviation as ז”ל, or perhaps he mistakenly connected the ז”ל on the previous line to ר’ אברהם הרואה

Pp. 44ff. Stern argues that according to the Gaon, matter existed eternally and the world was created from this eternal matter. If this was the case, it would be quite significant. Yet I believe that Stern misunderstands what the Gaon is saying. Stern himself quotes the Gaon as explaining that creation means “created from that which exists above.” As I see it, what this means is that matter “found” in the Divine was brought into the world, e.g., through emanation. But this is not the same as speaking of eternal matter, even eternal matter that is lacking form, as these exist apart from God.

With regard to the Gaon and creation, see also R. David Luria’s commentary to Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 51 n. 17, where he cites a manuscript comment of the Gaon that the world is eternally created. This same viewpoint is shared by R. Hayyim of Volozhin, Nefesh ha-Hayyim ch. 13. I don’t see how this can be reconciled with the Gaon’s comment at the beginning of Aderet Eliyahu that time itself is a creation, and he further speaks of an actual moment of the world’s creation:

בראשית: ב’ הוא ב’ הזמניי. כמו ביום. מפני שהזמן עצמו נברא והב’ מורה על עת הבריאה שהיה בחלק הראשון מהזמן הנברא

If matter is eternal, as Stern claims, or even eternally created, then time is also eternal. But this is clearly not what the Gaon says in the text just quoted.

P. 80. Stern notes that the Gaon’s interpretation of the Mishnah was not bound to how the Talmud explained matters. This is correct, and many people have written on the matter. I mention this only to call attention to the comments of the great genius, R. Meshulam Roth, in his Kol Mevasser, vol. 2, pp. 120-121, 128-129, who felt constrained to argue against this notion. I think it will be obvious to readers that R. Roth’s interpretations of the Gaon are based on his own dogmatic assumption, which he states explicitly, that it is unacceptable to interpret the Mishnah in a way that diverges from the talmudic interpretation.

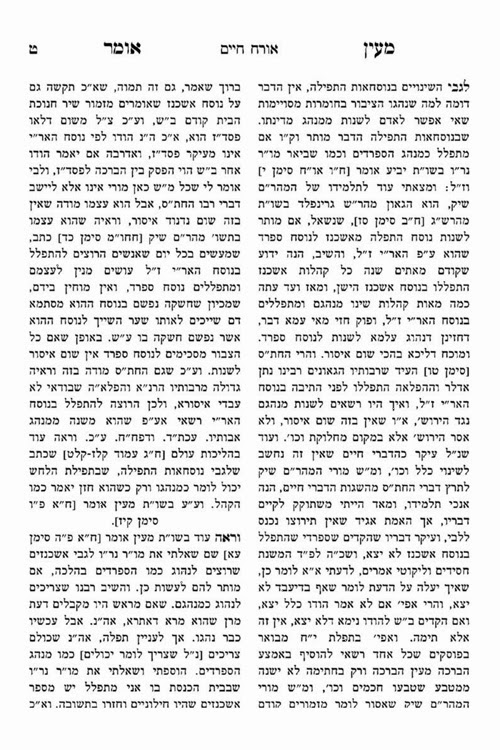

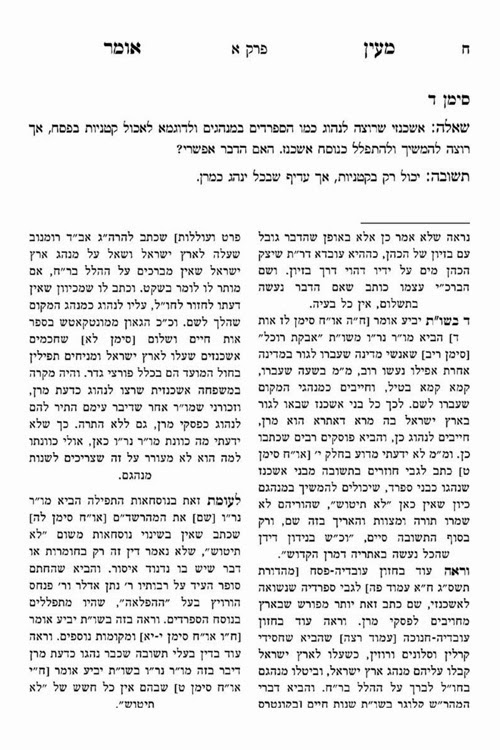

P. 97. Stern writes:

Contrast Elijah’s vision with the picture of intimacy expressed by Rabbi Pinchas of Korzec (1726-1791): “Prayer is like intercourse with the Divine Presence. At the beginning of intercourse there are motions. Similarly, there is a need for motion in prayer. One should move when beginning to pray. Later on, one can stand without moving, attached to the Divine Presence with a powerful bond. As a result of the motions alone one can attain dvekut.”

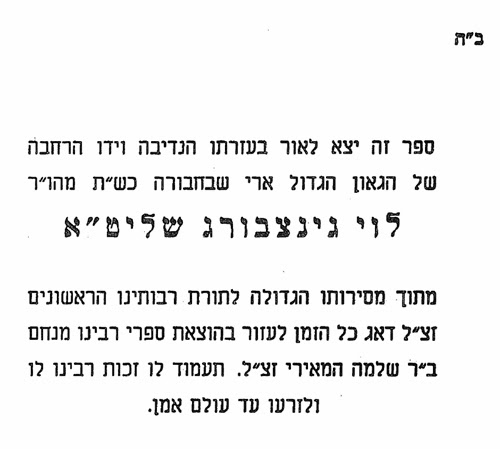

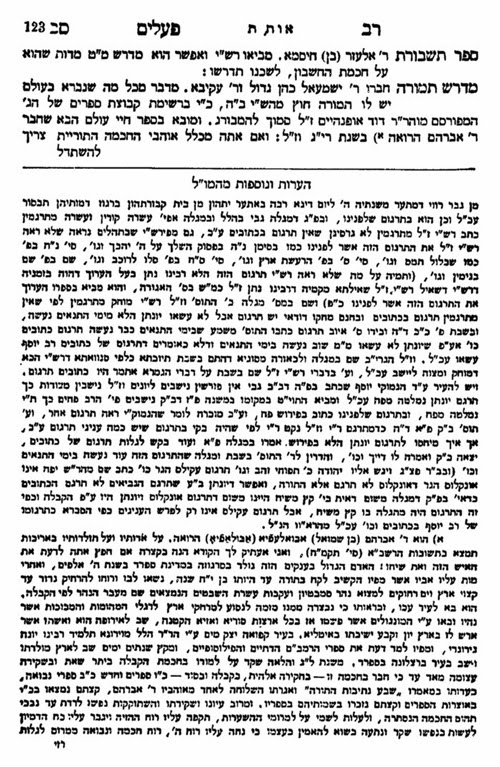

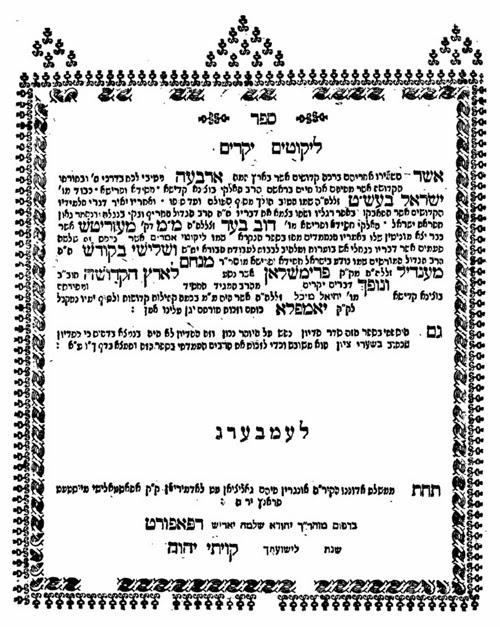

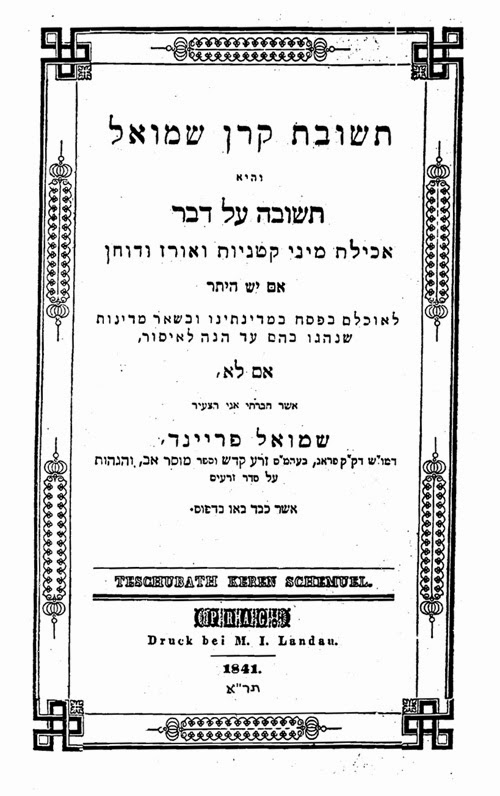

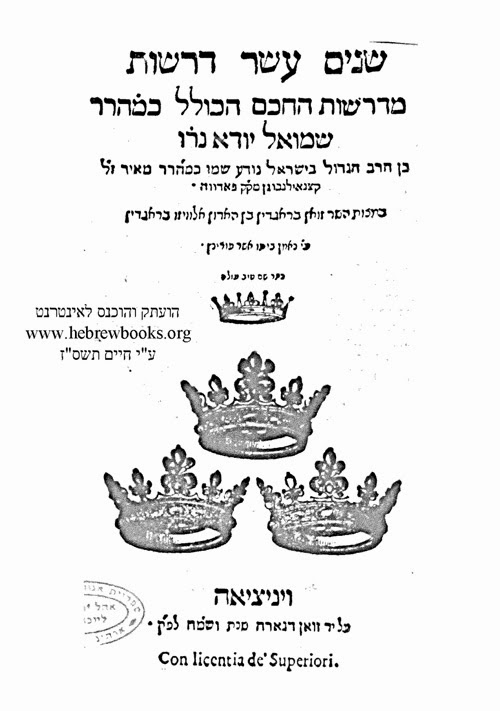

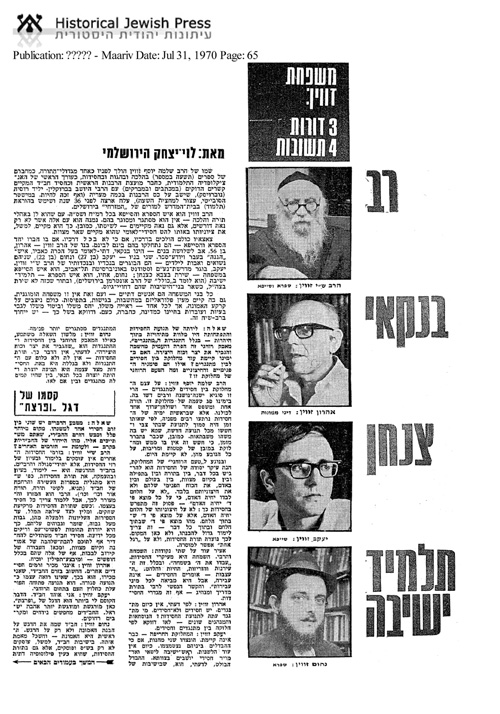

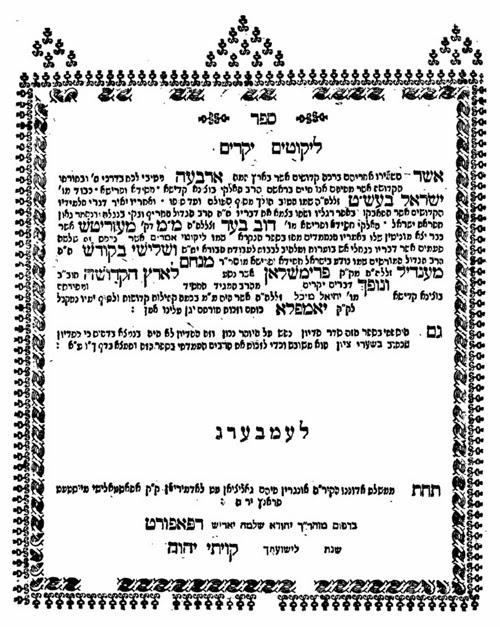

In the note the source for this quotation is given as

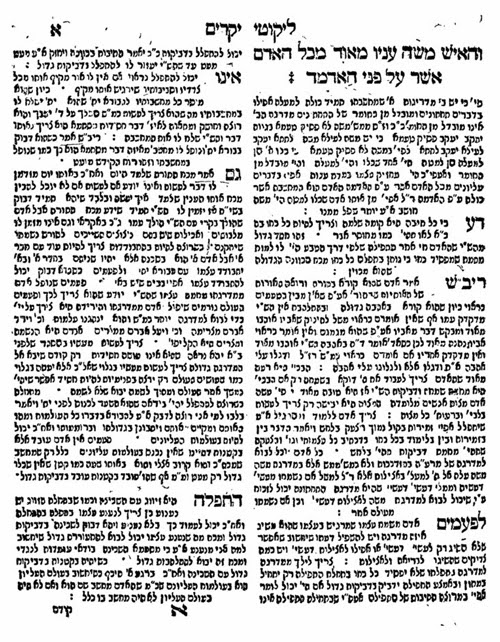

Likutim Yekarim, 18, and the bibliography tells us that the edition used is Lemberg, 1792 (the first edition). Yet there is some confusion here. R. Pinchas of Koretz indeed wrote a book entitled

Likutim Yekarim, but the book where the passage cited comes from is another

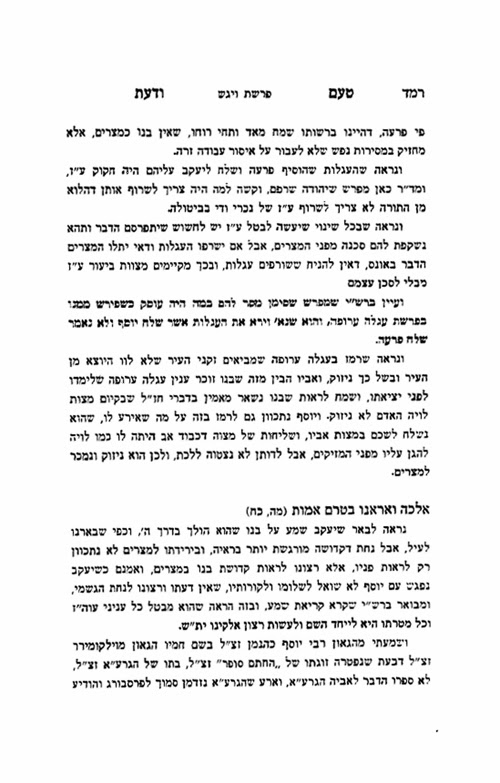

Likutim Yekarim, one that records the teachings of other early Hasidic teachers. Here is the title page.

Furthermore, the reader looking at page 18 in the first edition of (the correct) Likutim Yekarim will not find anything, as the text is on page 1a. In the 1974 edition the text is found in section 18, but as far as I can tell, these sections were only added in this edition.[17]

Here is the relevant page from the first edition, and the comment referred to is in the last paragraph. The last sentence of the translation quoted above (“As a result . . .”) is not an accurate rendering of the Hebrew sentence that begins מכח מה שמנענע

P. 102: “While it is doubtful that Elijah endorsed or defended Eibeschuetz’s or Luzzatto’s Sabbatian tendencies, he never publicly condemned their works.” Instead of the word “doubtful,” which leaves some room for question, the sentence should say that “it is certain that Elijah never endorsed or defended . . .” I leave aside for now the question of why Stern is so certain that Luzzatto had Sabbatian tendencies, and simply note that the Gaon would have rejected such an assumption in the strongest terms. The Eibeschuetz case is more complicated,[18] but I don’t understand how “Eibeschuetz’s Sabbatian proclivities were revealed when his son Wolff was unmasked as a closet Sabbatian” (p. 99). Since when do the actions of a son determine the stance of a father?

Let us now return to the issue of the Gaon’s view of philosophy, which was mentioned earlier in this post, and when I refer to philosophy I have in mind rationalism. Stern, p. 129, argues that the Gaon was not opposed to philosophy and as evidence for this proposition notes that the Gaon uses Aristotelian terms, cites the Guide once in his Aderet Eliyahu, and procured a copy of Aristotle’s Ethics. He then writes, “This evidence has led some to suggest that Elijah objected to a materialistic or epicurean lifestyle often associated with philosophy, but not to philosophy’s heuristic value.”

While I think that Stern is indeed correct that the Gaon saw heuristic value in philosophy, I was still quite surprised when I read this sentence, since I had never heard of anyone who argued that the Gaon’s only concern with philosophy was the materialistic lifestyle associated with it. When I looked in Stern’s note (p. 246 n. 55) it didn’t help. This is what appears in the note:

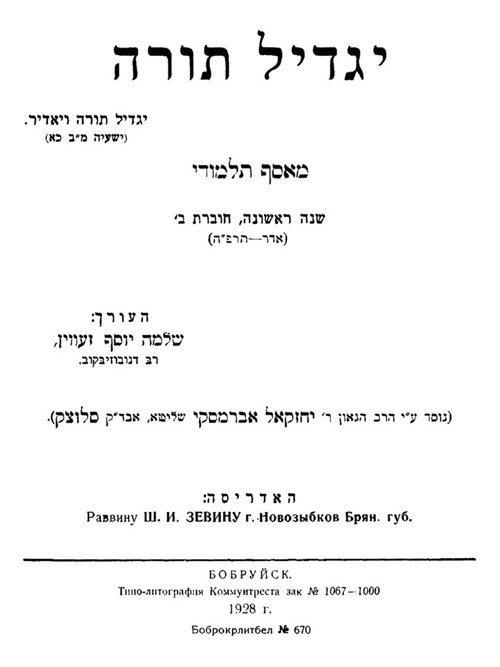

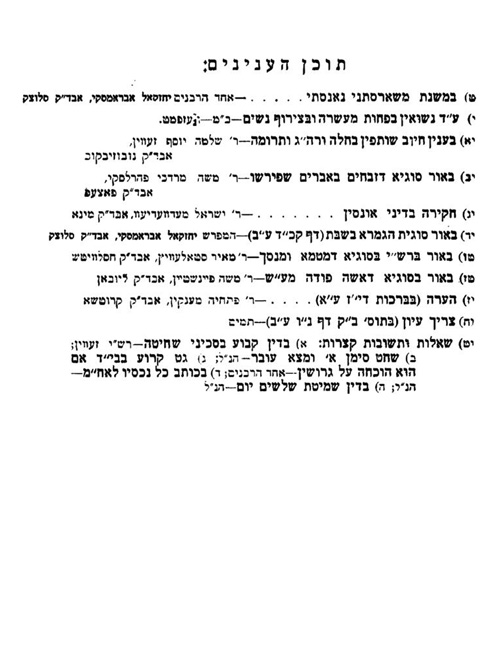

See Moshe Philip, ed., Sefer Mishlei im Biur ha-Gra (Petach Tikvah: 2001), 441 and Eliyahu Stern, “Philosophy and Dissimulation in Elijah of Vilna’s Writings and Legacy,” Revue Internationale de Philosophie (forthcoming). On Elijah reading Aristotle, see his letter to Rabbi Shaul of Amsterdam recorded in Tzvi ha-Levi Horowitz, Kitvei ha-Geonim (Warsaw: 1938 [should be 1928]), 3-10.

I don’t know what is intended by the first reference, as there is a typo since the volume does not contain 441 pages. Stern’s forthcoming article can only be discussed when it appears in print, but the book under review does not give any reference to others who argued that the Gaon had no substantive opposition to philosophy. Also, contrary to what Stern states here, the Gaon did not write to R. Saul of Amsterdam asking him to send him the Ethics. The letter Stern refers to was actually written by the Gaon’s brother, R. Yissakhar Ber.[19]

See Kitvei ha-Geonim, p. 4a. On p. 44, Stern states that the letter was written by both the Gaon and his brother. This, I think, is closer to the truth. I say this because the Gaon’s brother requested לקנות בשבילנו ולשלוח לנו, although this could also just be the writing style he used. However, there are lots of reasons why people read books, and this alone does not mean that one is positively inclined to a subject. The greatest of all Jewish philosophers, Maimonides, tells us that he read all the works of Sabian idolatry that he could get his hands on (Guide 3:29). It would also be more significant if instead of the Ethics, the book requested of R. Saul of Amsterdam was Aristotle’s Metaphysics. But I don’t want to make too much of this, since I am convinced by Stern that the Gaon saw some value with philosophy. But contrary to Stern, I would add that the Gaon also saw great dangers in philosophy.

In the note directly following the one just referred to, Stern concludes based upon the introduction of R. Menahem Mendel of Shklov to the Gaon’s commentary to Avot and R. Israel of Shklov’s introduction to his Peat ha-Shulhan that “Elijah was secretly positively inclined to the study of philosophy.” He again refers to his forthcoming article where he develops this point. As mentioned already, discussion of this article must wait until it appears in print. In the meantime, however, it is difficult to accept this point without a clear articulation of what exactly Stern means by “study of philosophy”, since in R. Israel of Shklov’s introduction to Peat ha-Shulhan he writes as follows:

ועל חכמת הפילוסופי’ אמר [הגר”א] שלמד אותה לתכליתה ולא הוציא ממנה רק ב’ דברים טובים . . . והשאר צריך להשליכה החוצה.

R. Israel of Shklov also notes that the Gaon knew חכמת הכישוף which contradicts Stern’s statement that according to the Gaon “references to demons, magic, charms, and other irrational objects and ideas cannot be ignored—though not per se because he thinks they actually exist.” (p. 129).

See also Ma’aseh Rav (Jerusalem, 1906), Siah Eliyahu, p. 21b (no. 61(, which states that the Gaon would not study R. Bahya Ibn Paquda’s philosophically based Sha’ar ha-Yihud (in the Hovot ha-Levavot):

והי’ מחבב הגר”א ז”ל ס’ מנורת המאור וס’ חובת הלבבות זולת שער היחוד ובמקום שער היחוד הי’ אומר שילמדו בס’ הכוזרי הראשון שהוא קדוש וטהור ועיקרי אמונת ישראל ותורה תלוין בו.

There is another passage that is relevant, but as far as I know has not been cited in any of the scholarly discussions about the Gaon and philosophy. R. Hillel Rivlin, Kol ha-Tor (Bnei Brak, 1969), ch. 5:2, quotes the Gaon as saying the following about philosophy, and you can’t get any clearer than this:

את חכמת הפילוסיפיה למדה לתכליתה ולא מצא בה כי אם דברים אחדים שמקורם לוקח מחז”ל ועל השאר אמר, שאין בה לא הגיון ולא צדק ומיוסדת על אפיקורסות אווילית.

As mentioned, you can’t get any clearer than this, but I realize that this is not the Gaon speaking but rather a student, so it is possible to argue that he, and also R. Israel of Shklov, didn’t properly portray their teacher.

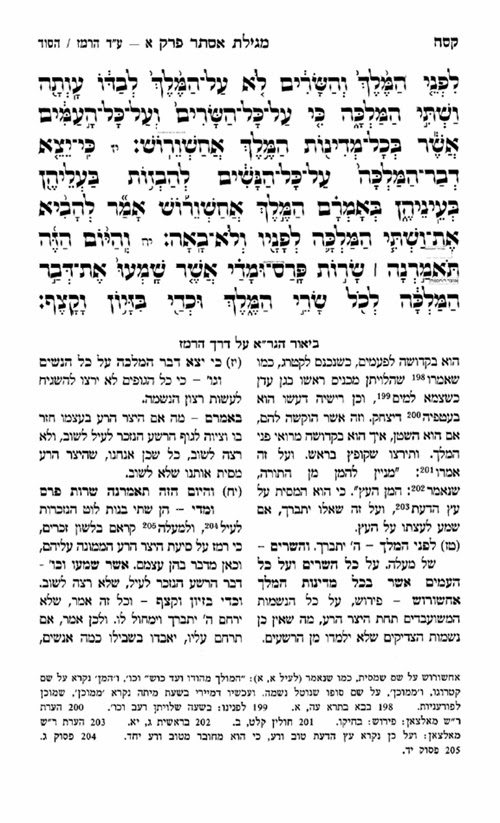

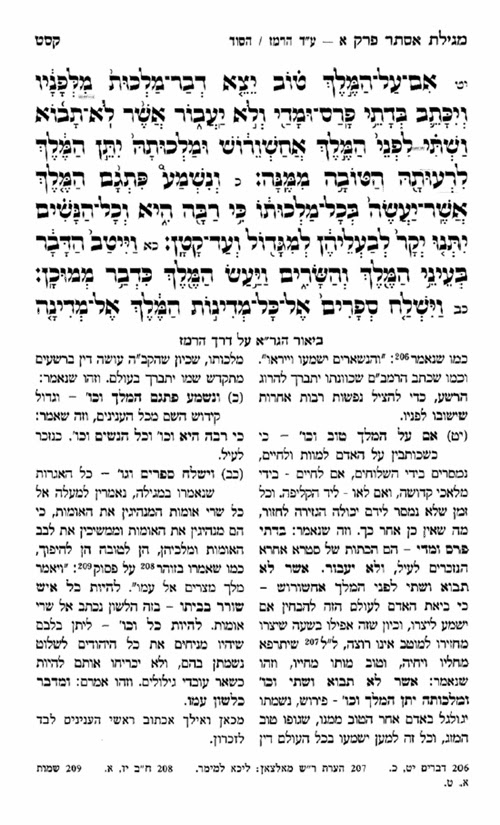

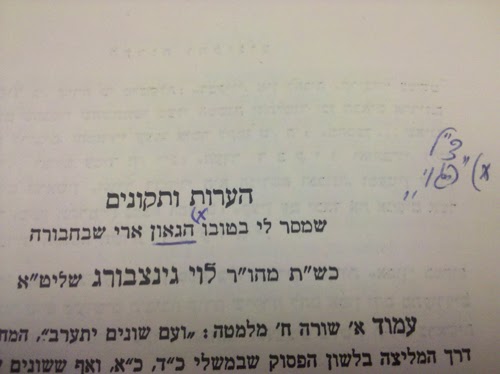

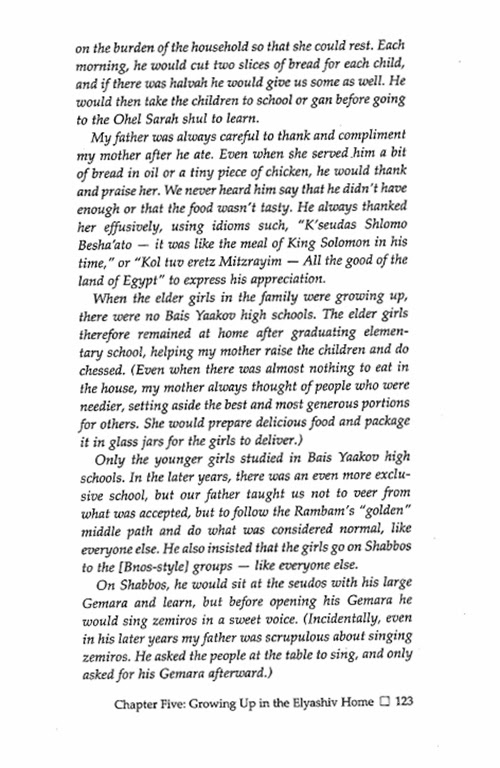

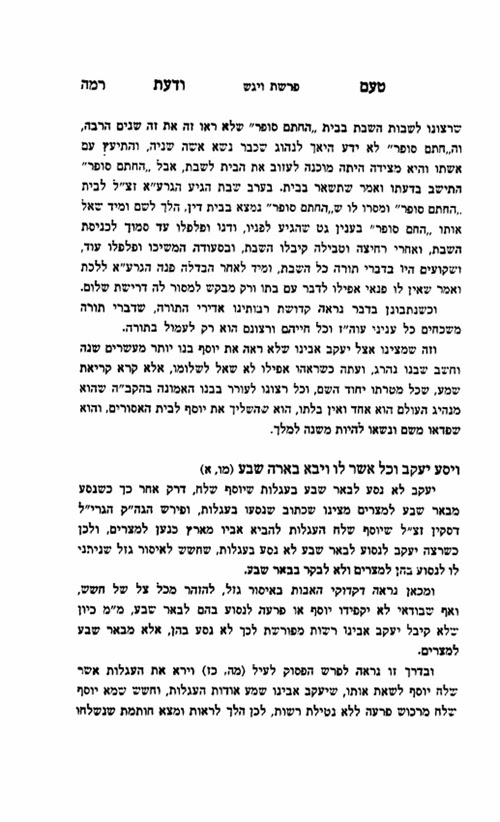

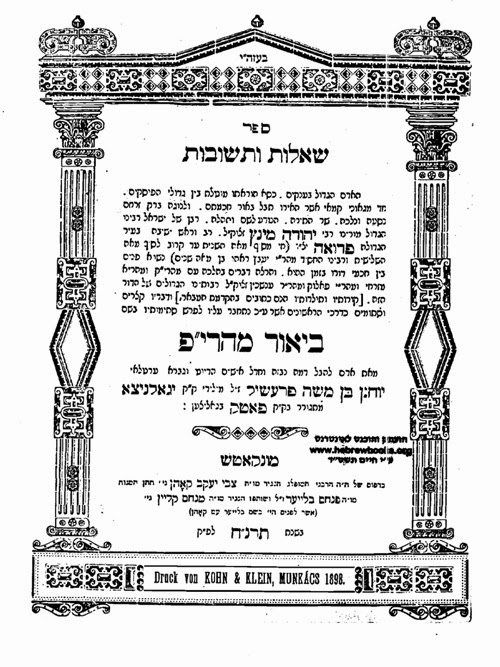

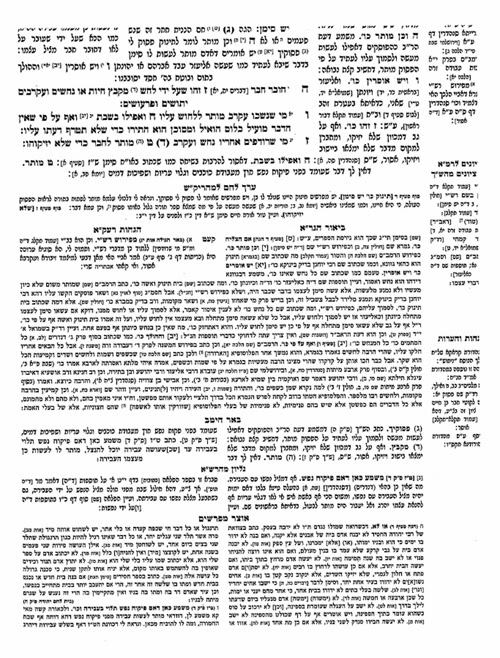

The passage that creates so many problems for Stern’s thesis is found in the Gaon’s commentary to

Yoreh Deah 179:13. In this text, the Gaon famously attacks Maimonides for being led astray by “accursed philosophy.”

Stern argues that the Gaon does not oppose the study of (even rationalist) philosophy per se. Rather, his opposition is directed at how “a philosophical approach may ignore linguistic nuance” (p. 129). I think this is very unlikely, and it appears to me that Stern is trying to force his interpretation into the words of the Gaon when the more likely, and natural, interpretation is that the Gaon indeed opposes the study of (rationalist) philosophy.[20] (On p. 130 Stern claims that the Gaon was not opposed to the study of “secular philosophy” which is an even more far-reaching claim.) Beyond what the Gaon writes in his comment on the Shulhan Arukh, there is the way he writes it, which unfortunately is not reflected in Stern’s translation. Here is how Stern renders the first part of the text:

All those who came after Maimonides differed [because they did not use his rational allegorical interpretive technique]. For many times we find magical incantations mentioned in the Talmud. Maimonides and philosophers claimed that such magical writings and incantations, and devils, are all false. However, he [Maimonides] was already reprimanded for such an interpretation. For we have found many accounts in the Talmud about magical incantations and writings. . . . Philosophy is mistaken in a majority of cases when it interprets the Talmud in a superficial manner and destroys the sensus literalis of the text. But one should not think that I in any way, Heaven forbid, actually believe in them or in what they stand for.

In this comment the Gaon writes:

והוא נמשך אחר הפלוסופיא הארורה .

This means that Maimonides “followed after the accursed philosophy.” However, Stern mistakenly translates these words: “Maimonides and philosophers claimed.”

Later in his comment the Gaon writes:

והפלסופיא הטתו ברוב לקחה לפרש הגמרא הכל בדרך הלציי

Stern translates this as “Philosophy is mistaken in a majority of cases when it interprets the Talmud in a superficial manner.” This too is a incorrect translation. What the Gaon is saying is that philosophy misled Maimonides to falsely explain the Talmud. So again, we see the great dangers of philosophy, and how it was able to lead astray even Maimonides. (There is nothing in the Gaon’s comment about “a majority of cases”). The final words quoted from the Gaon, בדרך הלציי, do not mean “superficial manner.” They mean “in a figurative sense.”

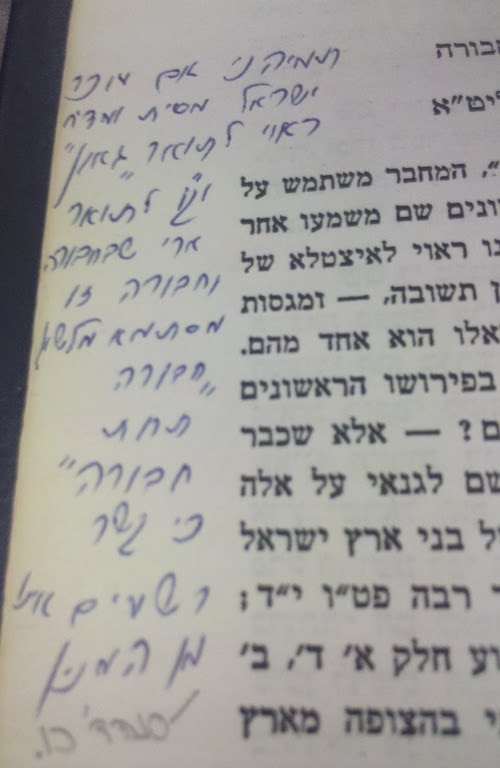

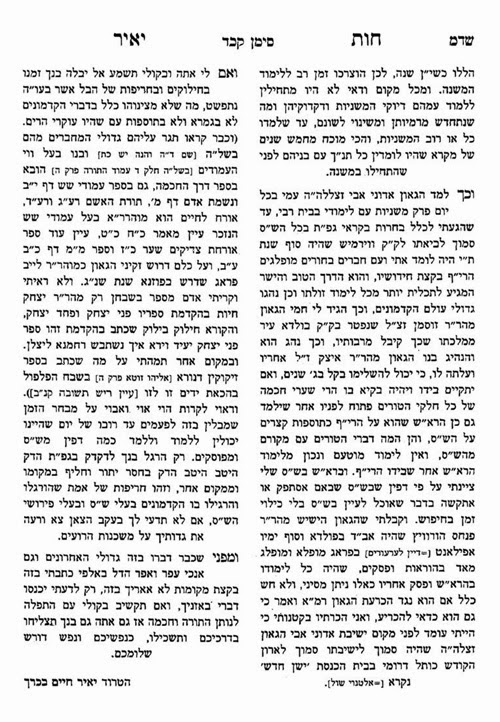

What can we say about the Gaon and Maimonides’ Guide? Although I hadn’t investigated the matter properly, for awhile I thought that the Gaon didn’t study the Guide in a serious manner. Anyone who reads Stern will see that this is incorrect. In fact, the Guide was even studied in Vilna during the Gaon’s time. The following passage from Aliyot Eliyahu (Vilna, 1892), p. 13a, should have been cited in the text by Stern as exhibit no. 1, as it is a strong piece of evidence in support of his position. For some reason, it is only summarized in a note (p. 246 n. 58):

וסיפר לי הרב כו’ הישיש מ’ ישראל גארדאן רב בווילנא (אשר היה מכיר היטב את הגאון נ”ע ודירתו היה בחומת אביו וקודם פטירתו היה דר הגאון בחצר בהכנ”ס) אשר היה נכנס ויוצא כפעם בפעם בבית הגאון נ”ע ושמע פ”א אשר בא הרב ר’ טרייטיל ז”ל לפני הגאון והרעיש על אשר ראו עיניו שאנשים קבעו למודם בבהמ”ד בספר מורה נבוכים וביקש שהגאון ימחה בידם והגאון השיבו בחרי אף ואמר ומי יעיז לדבר נגד כבוד הרמב”ם וספרו אשר מי יתנני ואהיה עמו במחיצתו בגן עדן.

There is no question that this report complicates the picture and shows that the Gaon’s view of the Guide was more complex than often portrayed. We see from it that unlike others, the Gaon, despite his strong criticism of Maimonides and general opposition to rationalist philosophy, nevertheless believed that the Guide had value and qualified scholars should not be prevented from studying it.

After quoting this passage in Aliyot Eliyahu, R. Shlomo Korah adds, “There is a story about someone who asked his rebbe if it is permitted to study the Guide. He replied, ‘The Rambam permits it —הרמב”ם מתיר ”.[21]

Alan Brill has also made the case that the Gaon saw value in philosophy and calls attention to the fact that in a text attributed to the Gaon, there is a summary of a section of the

Guide. See his “Auxiliary to

Hokhmah: The Writings of the Vilna Gaon and Philosophical Terminology, in Moshe Hallamish, et al., eds.,

Ha-Gra u-Veit Midrasho (Ramat Gan, 2003), p. 10. This shows that philosophy has value, as I too acknowledge, but this has nothing to do with rationalism, which the Gaon strongly opposed.

It is also worth noting that R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady, in responding to the reported theological objections that the Gaon expressed about early hasidut, wrote as follows[22]:

ומי יתן ידעתיו ואנחהו ואערכה לפניו משפטינו להסיר מעלינו כל תלונותיו וטענותיו הפילוסיפיות אשר הלך בעקבותיהם, לפי דברי תלמידיו הנ”ל, לחקור אלקות בשכל אנושי

In other words, and this is really ironic, R. Shneur Zalman assumes that Gaon was led astray by philosophy and that explains his objections![23]

The reason I had my mistaken assumption that the Gaon didn’t study the Guide in any significant way was because the Gaon didn’t refer to it in his commentary to the Shulhan Arukh, even when he had the opportunity, such as in his note to Yoreh Deah 179:13. Another place where he could have referred to the Guide is in the very first halakhah in Orah Hayyim. R. Moses Isserles is quoting from Maimonides’ Guide, and rather than refer the reader to this, the Gaon offers sources for the Rama’s formulation from rabbinic literature. Yet even before reading Stern’s book I should have seen that the Rama in Darkhei Moshe tells us that he is quoting the Guide, and one should assume that the Gaon saw this text.

This is how R. Isserles begins the Darkhei Moshe (and he begins the Shulhan Arukh similarly):

כתב הרמב”ם בספר מורה הנבוכים חלק ג’ פרק נב שמיד שאדם ניעור משנתו בבוקר מיד יחשוב בלבו לפני מי הוא שוכב וידע שהמלך מלכי המלכים הקב”ה יתעלה חופף עליו שנאמר (ישעיה ו, ג) ) מלא כל הארץ כבודו.

R. Isserles quotes Maimonides as saying that as soon as you wake up in the morning you should think about God. Yet if you look at Guide 3:52 that he is quoting you find something interesting. Here is the passage in Ibn Tibbon’s translation (which is what the Rama used).

מי שיבחר בשלמות האנושי ושיהיה איש הא-להים באמת יעור משינתו וידע שהמלך הגדול המחופף עליו והדבק עמו תמיד הוא גדול מכל מלך בשר ודם ואילו היה דוד ושלמה, והמלך ההוא הדבק המחופף הוא השכל השופע עלינו שהוא הדבוק אשר בינינו ובין הש”י . . . וכבר ידעת הזהירם מלכת בקומה זקופה, משום מלא כל הארץ כבודו.

Where does the Rama get his formulation that as soon as one awakes – מיד שאדם ניעור משנתו – he should think of God? It comes from Maimonides’ words we just read: יעור משינתו. As pointed out by Raphael Speyer,[24] it seems that the Rama simply misunderstood what Maimonides (in Ibn Tibbon’s translation) was saying. The words יעיר משינתו have nothing to do with awakening from sleep in any literal sense. Rather, the expression simply refers to people who are figuratively awakening from their slumber and can now recognize God’s presence. Therefore, there was no need for the Rama in seeking to make his point to include anything about getting up in the morning.

In the Datche’s editor’s response to Speyer, he pointed out another problem with the Rama’s formulation. While the Rama writes of מלך מלכי המלכים הקב”ה יתעלה חופף עליו, this is not what Maimonides says. According to Maimonides, “this king who cleaves to him and accompanies him is the intellect that overflows toward us and is the bond between us and Him, may He be exalted.” In other words, Maimonides is speaking about the Active Intellect yet the Rama turns this into God Himself. It is because of things like this that Yeshayahu Leibowitz was led to declare that the Rama “didn’t understand philosophy and didn’t understand the Guide of the Perplexed.” He also referred to the Rama’s Torat ha-Olah as a work of “pseudo-philosophy.”[25]

This might seem like an unfair statement, and I am sure that Yonah Ben Sasson would reject it,[26] but consider the following. No one could be regarded as a rabbinic scholar if all he studied was the Mishneh Torah, without examining the talmudic passages upon which the Mishneh Torah is based. In fact, I think all would agree that one can’t really understand the Mishneh Torah without knowing the talmudic sources. By the same token, one can’t really understand the Guide without knowing the Aristotelian sources upon which so much of Maimonides’ words are based. Yet the Rama tells us, in his famous letter to R. Solomon Luria,[27] that he never actually studied Aristotle and his only knowledge of him comes from Maimonides’ Guide and other Jewish sources.

כי אף שהבאתי מקצת דברי אריסטו מעידני עלי שמים וארץ שכל ימי לא עסקתי בשום ספר מספריו רק מה שעסקתי בספר המורה שיגעתי בו ומצאתי ת”ל [תהלה לא-ל] ושאר ספרי הטבע כשער השמים וכדומיהין, שחברו חז”ל ומהם כתבתי מה שכתבתי מדברי אריסטו.

Interestingly, I found one place, Torat ha-Olah 3:47, where the Rama speaks very disrespectfully of Maimonides’ philosophical knowledge, referring to it as foolishness.

ואין לך סכלות חכמתו גדולה מזה

Nevertheless, the Gaon placed the Rama together with Maimonides in his other sharp criticism of the latter[28]:

אבל לא ראו את הפרדס, לא הוא [הרמ”א] ולא הרמב”ם

To be continued

* * * *

Information about my summer trips to Spain, Central Europe, and Italy will be available soon. Anyone interested should check out the Torah in Motion website. Marc Glickman, one of the participants on last year’s tour to Central Europe, described it as follows: “It was great to meet Marc and he was a fantastic guide. The trip was like a living Seforim Blog post (I follow his posts religiously).” Thank you Marc!

Also for those interested, I will be speaking on R. Ovadiah Yosef at Ohab Zedek in NYC on December 17 at 8:15pm.