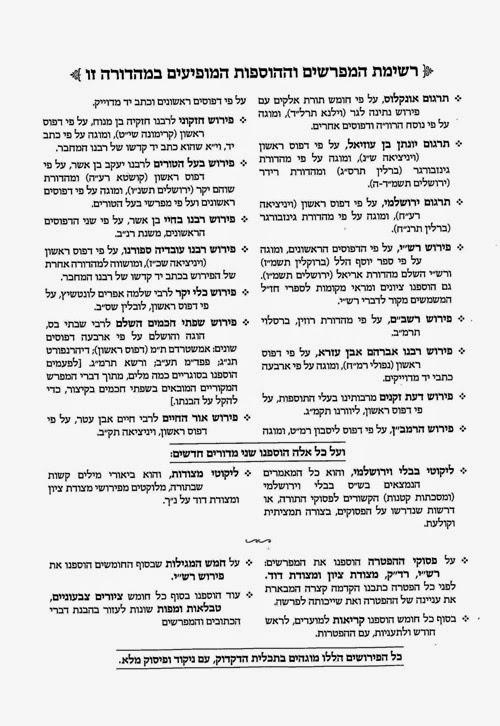

R. Hayyim Hirschensohn, Can One Kill an Am Ha’aretz on Shabbat? Physical Punishments and Lots More

1. In many earlier posts I have discussed R. Hayyim Hirschensohn, so let me pick up with him again.[1] In the Encyclopaedia Judaica’s article on R. Hirschensohn it tells us that he wrote a book Ateret Hakhamim published in 1874. Many people have been interested to see this book which was published when he was only seventeen years old. If you look at library catalogs you will not find anything. Yet if you look in Beit Eked Sefarim, the book is listed as published in Jerusalem, 1874, and this is where the EJ got its information. Beit Eked Sefarim gives the book the following subtitle:

קורות חכמת הטבע והפילוסופיה לפי השקפת אגדות חז”ל

As far as I can tell no such book was ever published in 1874 and I have no idea where the subtitle to the book came from. However, JNUL does have an unpublished manuscript from Hirschensohn with the title Ateret Hakhamim, and presumably that is where the confusion arose.

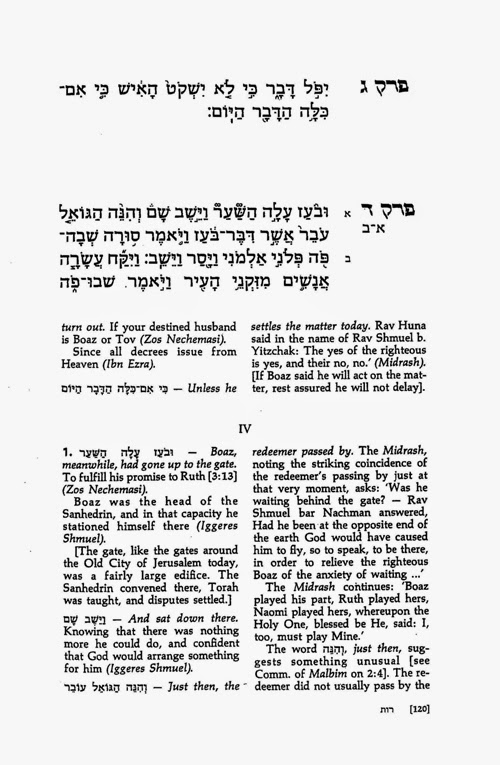

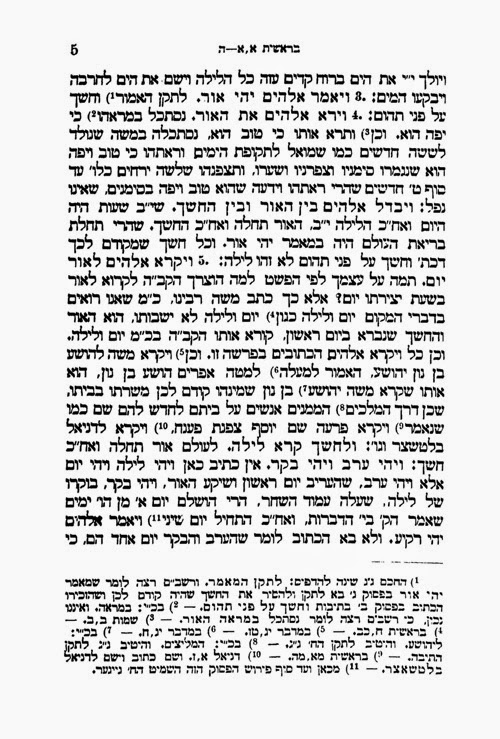

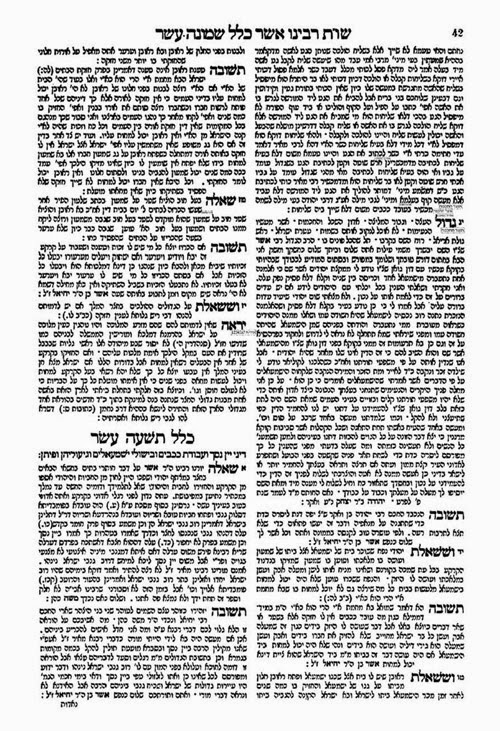

The first book by Hirschensohn is actually quite unknown, and is not mentioned by David Zohar in his list of Hirschensohn’s writings.[2] It is

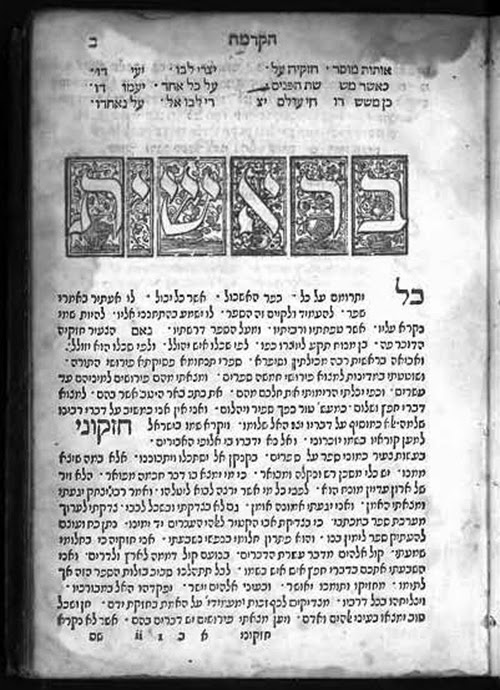

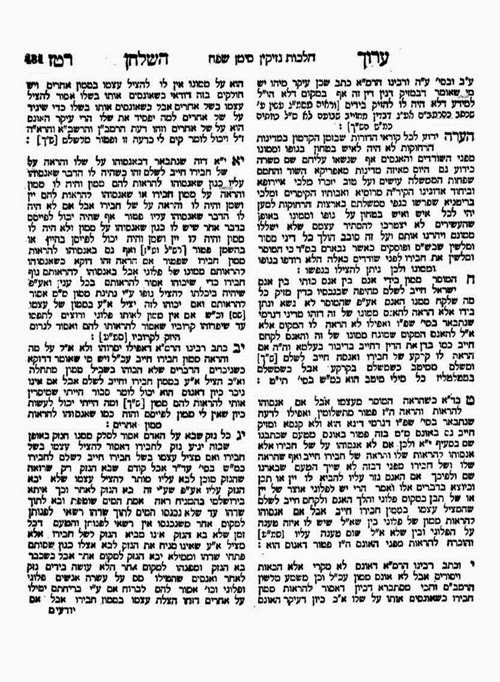

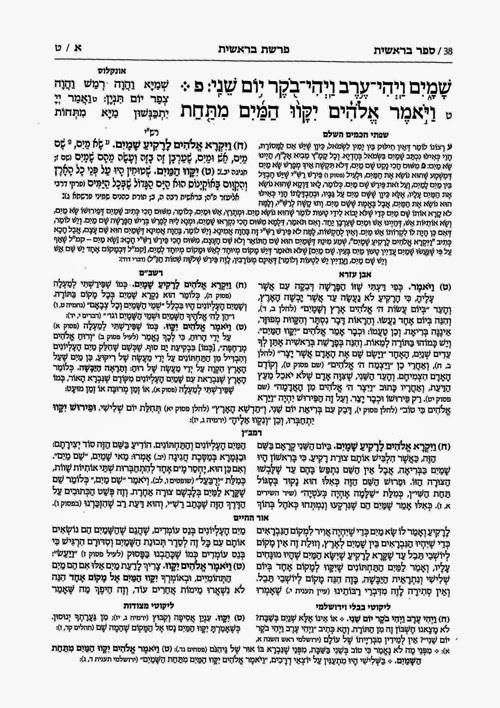

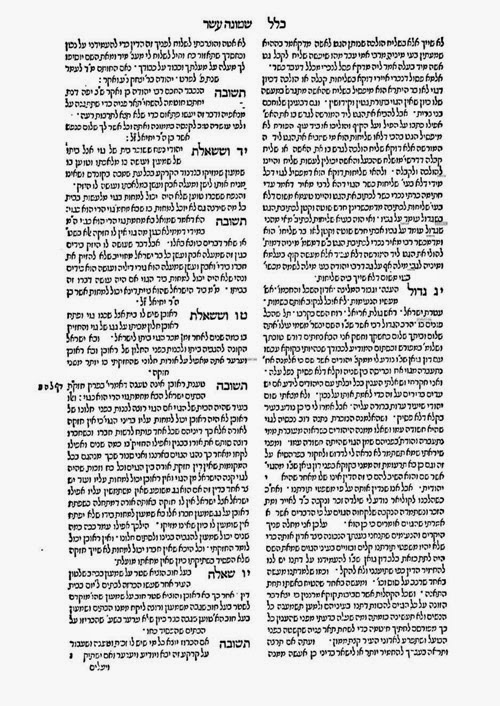

Ateret Zekenim, his commentary to R. Elijah Guttmacher’s

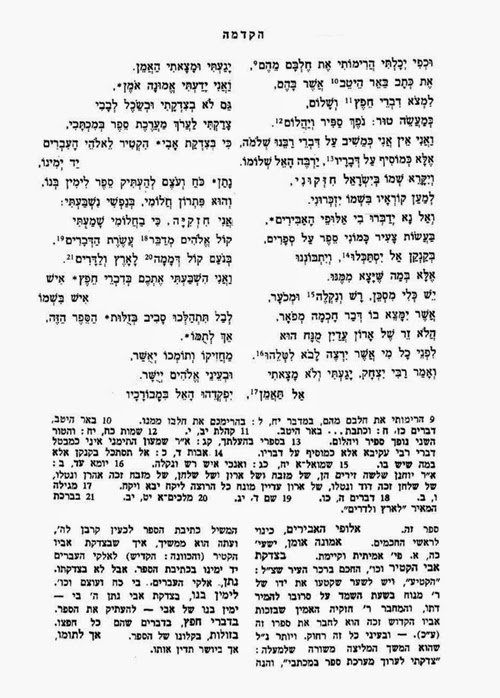

Sukkat Shalom, published in 1883. While this book is not on Otzar ha-Hokhmah we are fortunate that it is on hebrewbooks.org, and here is the title page.

R. Hirschensohn published R. Guttmacher’s

Sukkat Shalom from manuscript. The connection between the two was that R. Hirschensohn’s father, R. Jacob Mordechai, was close to Guttmacher and head of a yeshiva in Safed and later in Jerusalem that operated under R. Guttmacher’s auspices.[3]

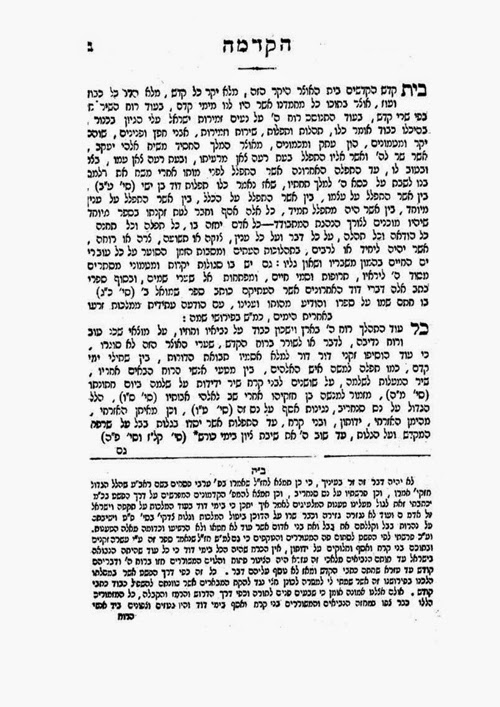

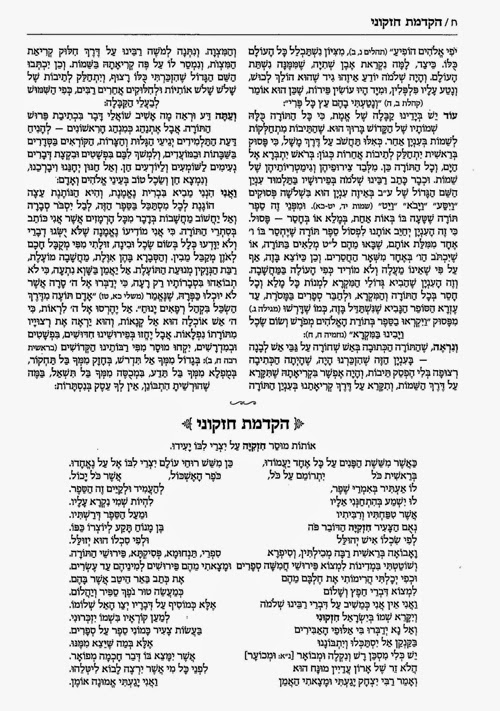

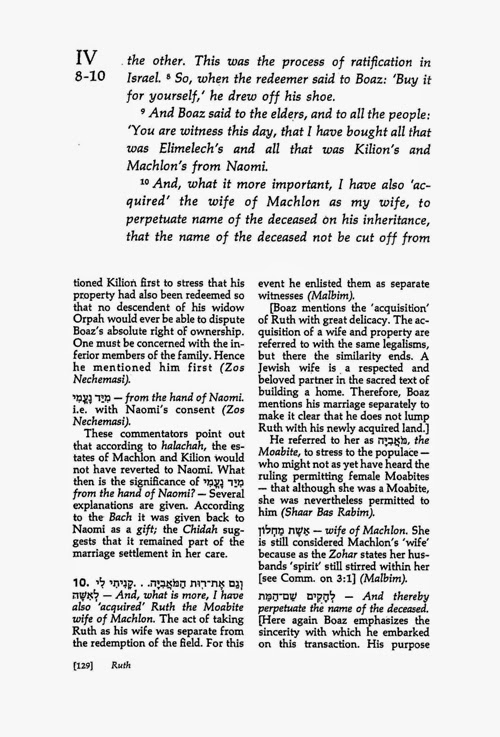

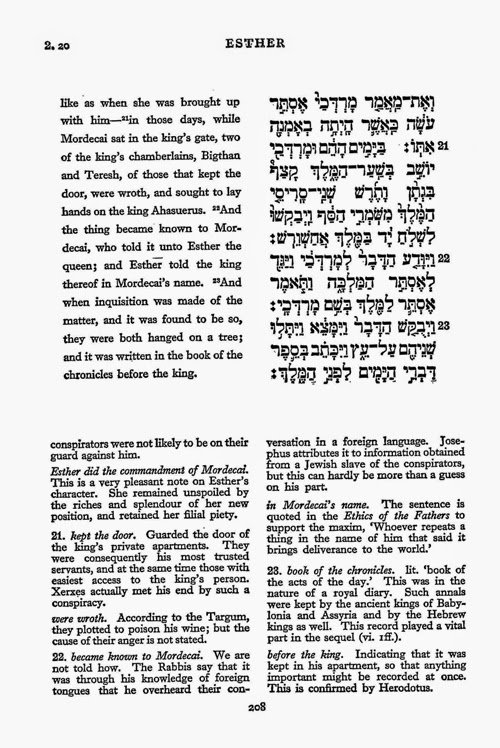

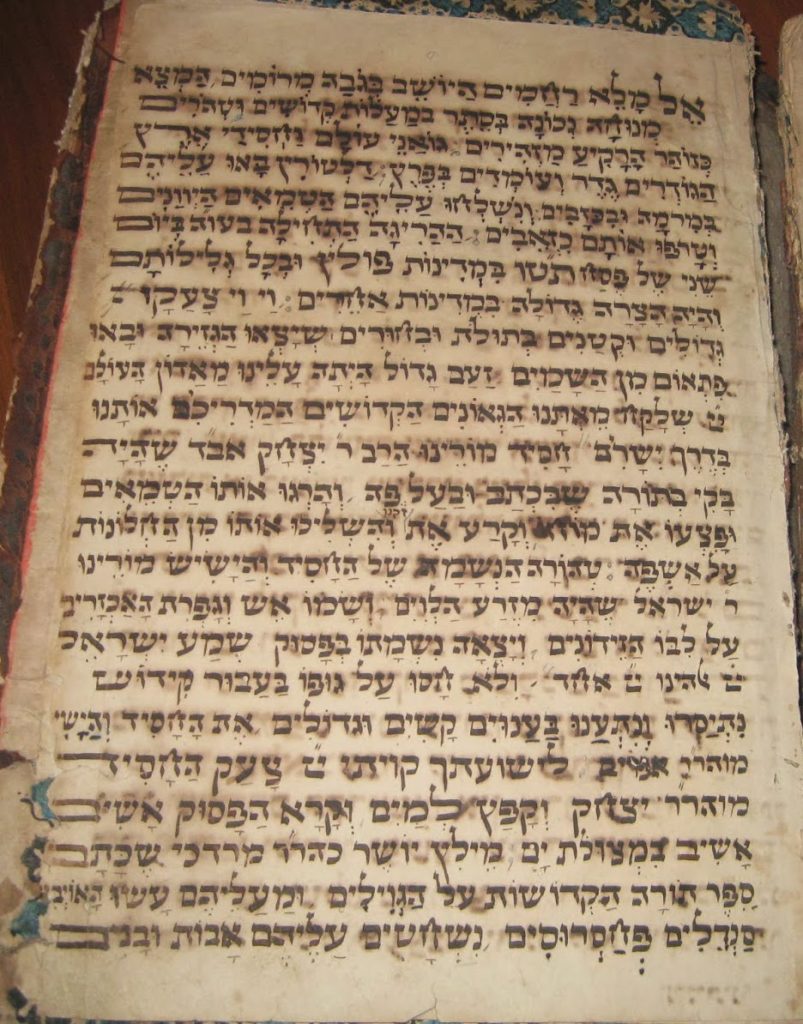

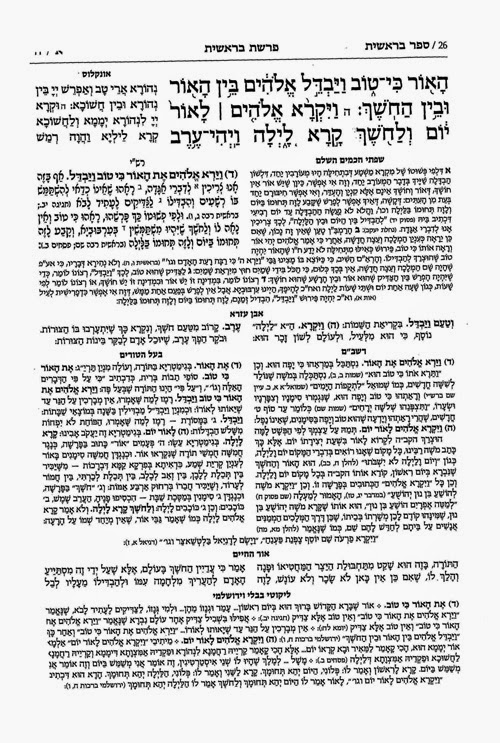

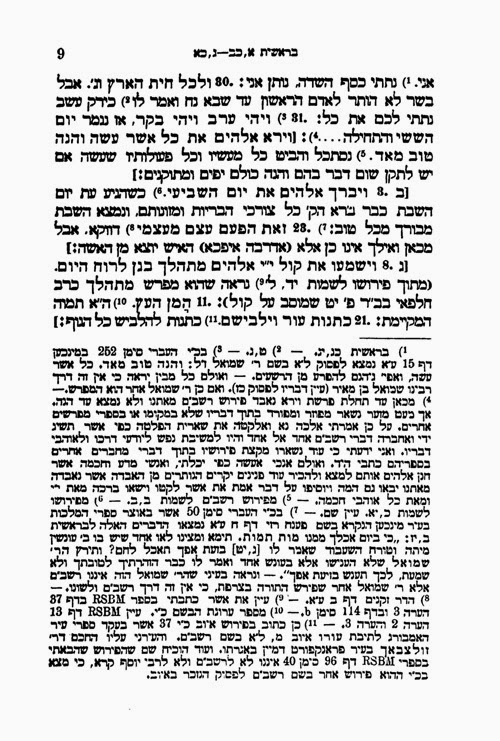

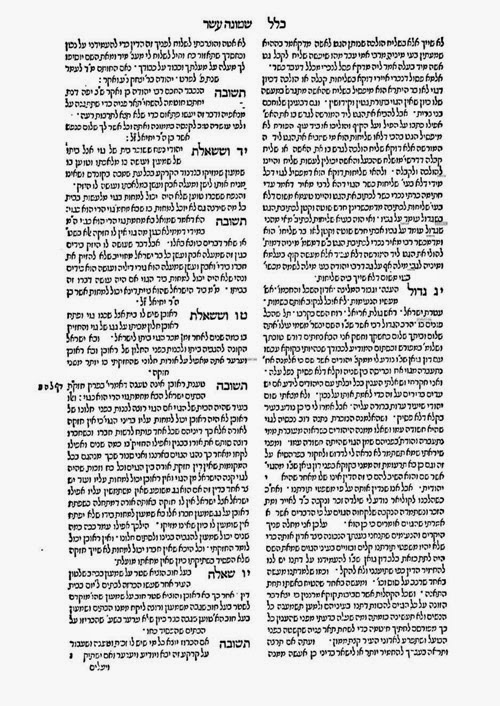

Sukkat Shalom was reprinted in 2000. Here is the title page.

Since this book is not on hebrewbooks.org or Otzar ha-Hokhmah, I think one can say that it qualifies as a “rare book.” In the introduction to this new printing, the editor tells us that the book was first published in 1883, but in the all too common haredi method, he does not tell the reader who first published it. He does tell us that his edition is based on the manuscript found in the New York Public Library, which must have come from R. Hirschensohn’s library.

When writing about a figure such as R. Hirschensohn, one of the central themes is developments in his thinking which is why the early writings are always so important. Therefore, this work must be studied by all who are interested in R. Hirschensohn. Ateret Zekenim shows R. Hirschensohn before he was exposed to secular studies and broadened himself. In this work, he is still a Jerusalem ben Torah with a limited curriculum, albeit more open-minded than many others in the Land of Israel during this period.[4]

Later in life he would even study Spinoza and write notes on the latter’s work. Yet he admitted that the feelings his writing on Spinoza raised in him were entirely the opposite of the spirit of religious feeling during Torah study, and he thus advised people to keep away from what he wrote, unless someone was particularly troubled by Spinoza’s ideas and needed to see a Jewish response.[5]

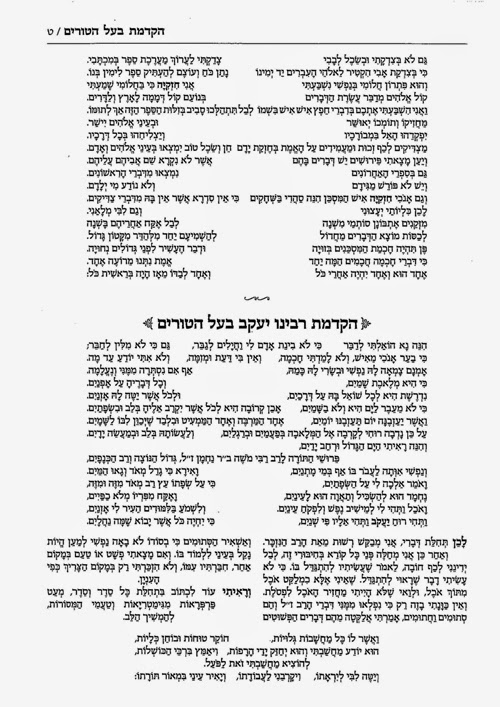

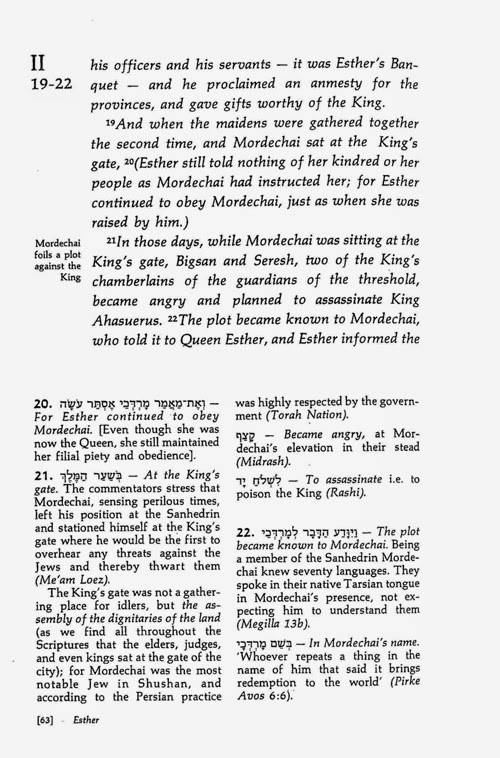

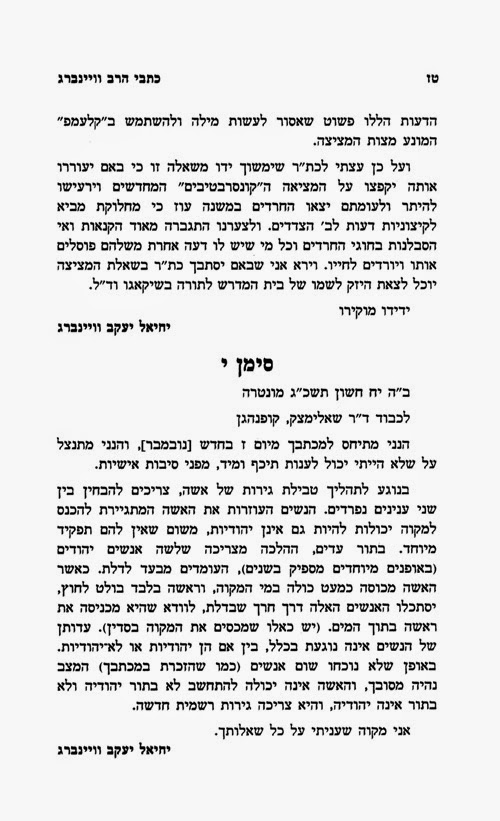

It is significant that even though R. Hirschensohn criticizes Spinoza, he does not relate to him as a heretic. He even attaches ז”ל after his name, as you can see from the title page of the second part of his Musagei Shav ve-ha-Emet.

I don’t know of any other rabbinic author who gives this type of honor to Spinoza, the heretic par excellence. In the preface to his discussion of Spinoza, R. Hirschensohn recounts what led him in 1903 to begin his study of the philosopher. On pp. 113ff. (second pagination, as are the other page numbers I refer to) R. Hirschensohn discusses Spinoza’s pantheism and states that he was not guilty of two of the big heresies: (1) regarding God as a corporeal being, or (2) avodah zarah. He was simply in error, and that was because he didn’t properly investigate matters. R. Hirschensohn even admires the way Spinoza stuck to his beliefs despite the persecution he suffered. He refused to give in to his opponents as from his perspective to do so would be a form of falsehood and idolatry. In other words, Spinoza and his opponents were equally well intentioned. In fact, all of them, including Spinoza, were tzaddikim! They simply had different perspectives on reality.

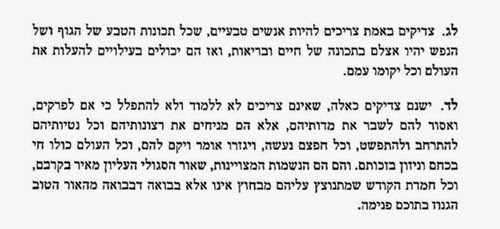

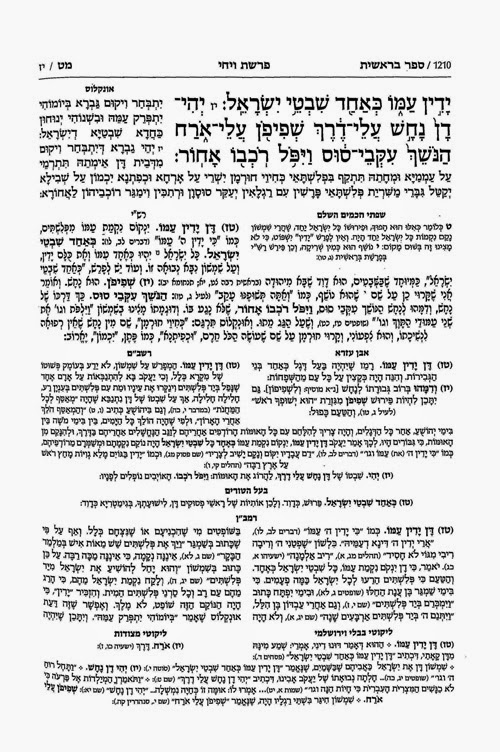

Here is what R. Hirschensohn writes on p. 115, words which are incredible coming from a rabbi and posek. As far as I know this is the only Orthodox defense of Spinoza.[6] (The word וברוך in the first sentence alludes to Spinoza’s name, and note also the words I have underlined.)

צדיק הוא שפינוזי לפי שטתו וברוך טעמו ונמוקו, ובצדקתו ותום לבבו סבל חרפת שונאיו ומנדיו וימסור נפשו וכבודו על קדוש השם, ולו הודה למתנגדיו אזי הי’ עובד אלהות הרבה, כאשר אנחנו היינו נחשבים לכופרים באלקים או עובדי ע”ז בשתוף לו הודינו אנחנו לשכלת שפינוזי באלוה, שני המתנגדים צדקו בדרכם ע”פ שיטתם המדעי ואת אלקים בקשו הרודף והנרדף, ושניהם צדיקים גמורים עובדי אלקים באמת ובלב שלם, כי כל המחלוקת אשר בינינו לשפינוזי היא רק מחלוקת מדעית, אשר אם כה ואם כה אין זה כפירה ונגיעה בדת ובאמונה, כאשר לא יהי’ נוגע לאמונה אם שני אנשים יחלקו שאחד יאמר שהארץ גדולה מהשמש והשני יאמר שהשמש גדולה

According to R. Hirschensohn, Spinoza made mistakes in his understanding of God, but this does not mean he was a heretic, since there is no obligation on Jews to investigate the nature of God. In other words, since there are no principles of faith regarding the nature of God, one such as Spinoza who errs in this matter cannot be regarded as a heretic as he has not uprooted any basic Jewish principles.[7] On p. 117 he writes:

לא נקרא בזה כופר באלוק ואפיקורס כי הוא לא אמר לאלוק נברא אתה הוא אומר שהוא מחויב המציאות וסבת עצמו, רק ייחס לו דבר שאין בו, נקרא בזה טועה לא כופר כי אין אנו מצווים בשום מקום לחקור ולידע מהות אלקים עלינו בדעת אלקים החוב רק לידע שיש שם מצוי ראשון ממציא כל נמצא כו’ החוב עלינו לידע ולהאמין מציאותו ולא לחקור ולידע את מהותו אפי’ מה לשלול ממנו . . . לא נצטונו בשום מקום לא בהתורה ולא בהנביאים גם לא בדחז”ל לידע ולחקור במהותו אדרבא נצטוינו שלא ללמד דברים אלו אלא לחכם ומבין מדעתו, כי לא נחוץ כלל לאמונה ודת החקירות בזה.

Following this, R. Hirschensohn states that since neither the Torah nor the Sages require that the masses educate themselves in philosophical matters, one cannot regard them as heretics for not being sophisticated in this area. The upshot of this, according to R. Hirschensohn, is that Rabad is correct in his criticism of Maimonides in

Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:7. That is, an honest mistake even in basic theological matters does not render one a heretic.

[8] What this means is that Spinoza also cannot be regarded as a heretic (and his mistake was not even in an

ikar emunah). R. Hirschensohn concludes by saying that in Heaven both Spinoza and his opponents have made peace with one another (p. 118).

מודה הראב”ד ז”ל שההגשמה היא שבוש הדעות אבל לא נקרא על ידי זה מין רק טועה ומכש”כ מין הגשמה הזאת של שפינוזי אשר נוכל לקרא אותה בשם הגשמה רוחנית, הוא רק טועה לא מין וכופר ח”ו ומכש”כ שלא נקרא עובד ע”ז, והותר הנדר. ובעלמא דקשוט עושה שלום במרומיו יעשה שלום בין נשמתו של שפינוזי ונשמת מתנגדיו. כי לכל העם בשגגה.

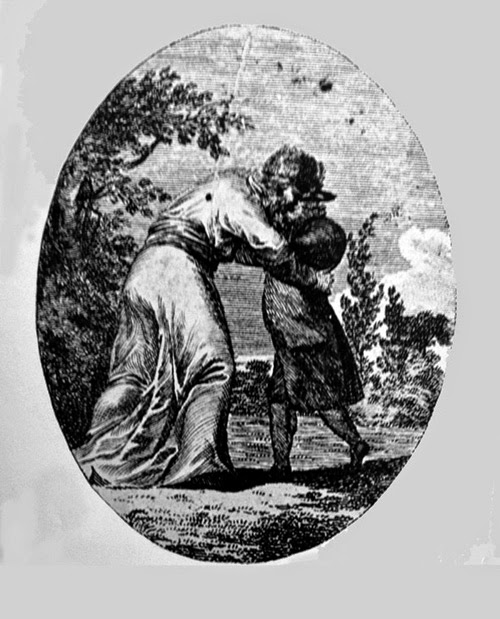

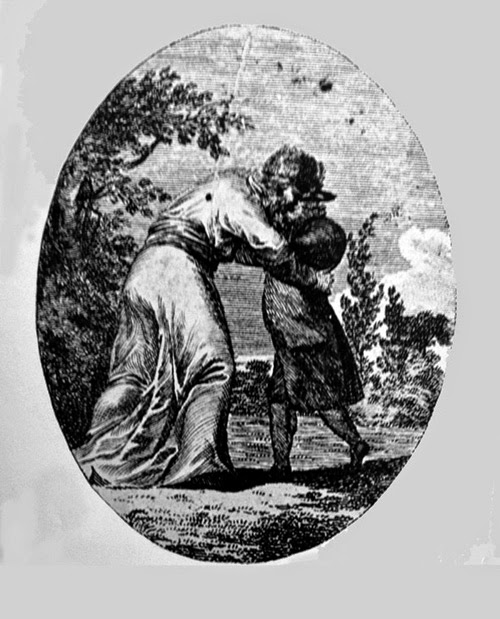

This reminds me of the famous picture of Mendelssohn and his antagonist R. Ezekiel Landau embracing in the afterlife. It appeared in the book

Alon Bakhut, published by Joseph Ha-Ephrati in 1793. (Mendelssohn was short and R. Landau was quite tall.)

S. also refers to the image

here and notes another example of antagonists making up in the World to Come, in this case R. Jacob Emden and R. Jonathan Eybschuetz.[9]

Since I will touch on the dogma of Torah mi-Sinai in the next post, let me also note the suggestive comment of R. Hirschensohn that until parashat Va-Yigash we find stories in the Torah that took place in dreams, but after this there are no such stories in dreams. Rather, everything took place in reality.[10] Unfortunately, he does not explain which stories prior to Va-Yigash he regards as having taken place in dreams. If all he meant were the stories of Abraham and the three angels, and Jacob wrestling with the angel, which were already mentioned by Maimonides,[11] then there is not much of significance in his comment. I therefore assume he has much more in mind, but as mentioned, he doesn’t reveal the particulars.

2. In my post

here I wrote “R. Asher Ben Jehiel,

She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rosh 18:13, deals with a case of a woman who was intimate with a non-Jew and became pregnant from him. R. Asher affirms the local rabbi’s decision to cut off her nose.” This passage is referred to by Louis Epstein,

Sex Laws and Customs in Judaism )New York, 1967), p. 173. In his note to this passage, Epstein writes, “Adret opposed this practice. See

Besamim Rosh, 192.” This is a very surprising note. Epstein was a great talmid hakham and also a learned academic scholar. I therefore can’t understand how he assumed that the Rashba’s responsum in

Besamim Rosh was authentic.

I have many notes to Besamim Rosh which I will one day turn into an article. The entire volume is one big game, meant to undermine traditional Judaism from the inside. People often assume that there are only a few “problematic” responsa, but this is incorrect, as there are loads of them, all with the same purpose in mind. Faced with the responsum of R. Asher which permitted mutilation, Saul Berlin could not put forth an alternative view in the name of R. Asher, so he attributed the forged responsum to the Rashba. In this responsum, “Rashba” responds to the very same inquiry that R. Asher was presented with, namely, was the questioner correct in ordering the removal of the nose of a woman who became pregnant from a non-Jewish man. In the question as it appears in Besamim Rosh, the pregnant woman is actually referred to as a ילדה, which is Berlin’s way of making R. Asher’s decision look even worse.

In his response, “Rashba” completely rejects R. Asher’s decision, stating that today there is no dinei nefashot, no kenasot, and certainly no mutilation. In this case, he tells us, the woman only violated a rabbinic prohibition, since there is no Torah prohibition on sex with a non-Jew. And even if it was a Torah prohibition there is no permission to mutilate her. “It is not proper to mutilate the daughters of Israel who are praised for their beauty.” It should be obvious to anyone who reads this responsum that we are seeing Saul Berlin’s attempt to put a kinder face on a troublesome aspect of medieval halakhah. The responsum anachronistically argues for a more humane approach to sinners than that presented by R. Asher, and is thus in line with Berlin’s wider struggle to reform traditional Judaism.[12]

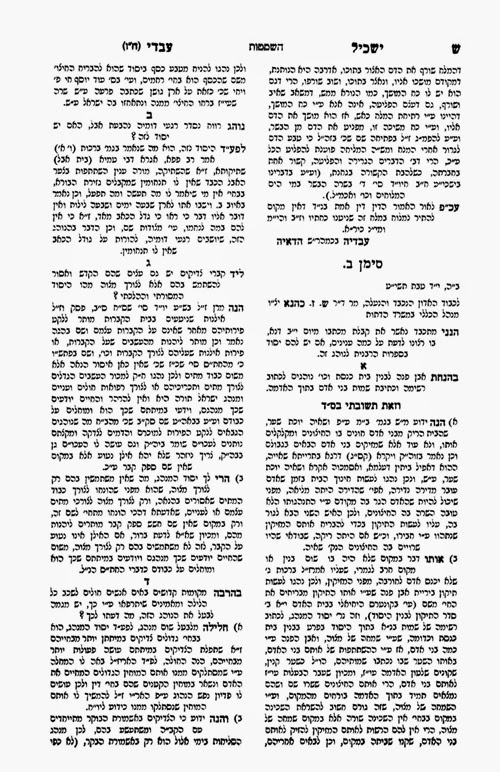

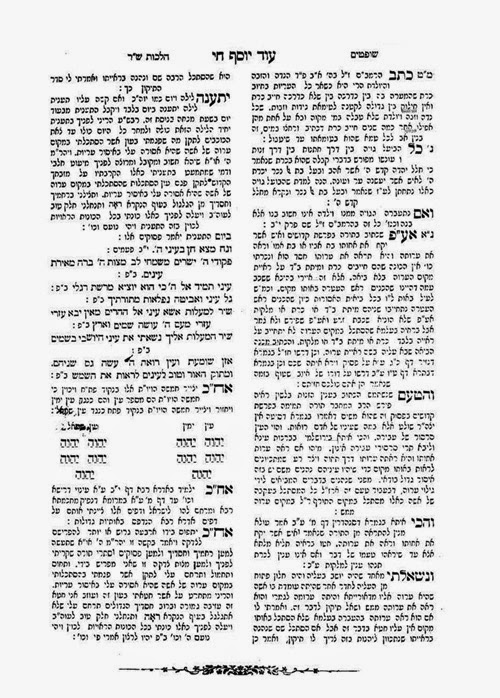

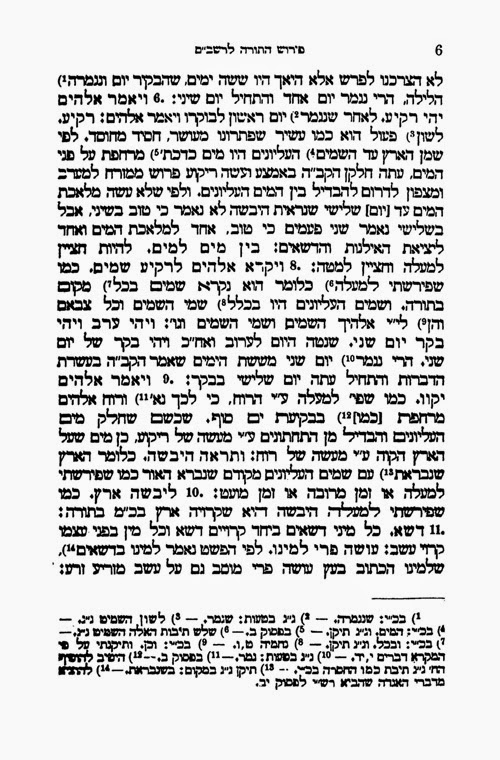

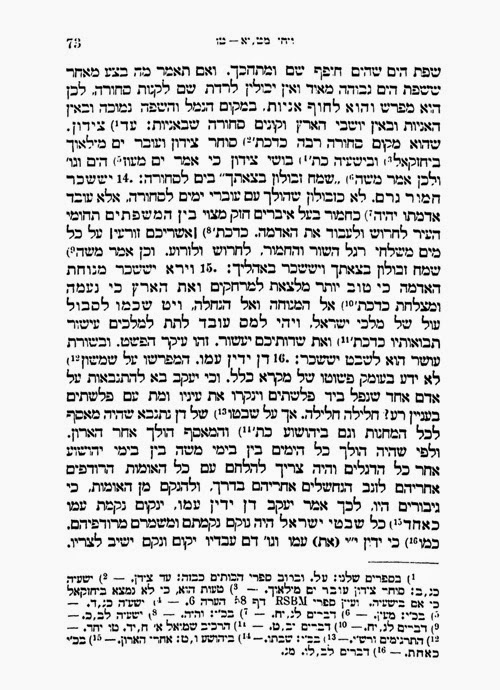

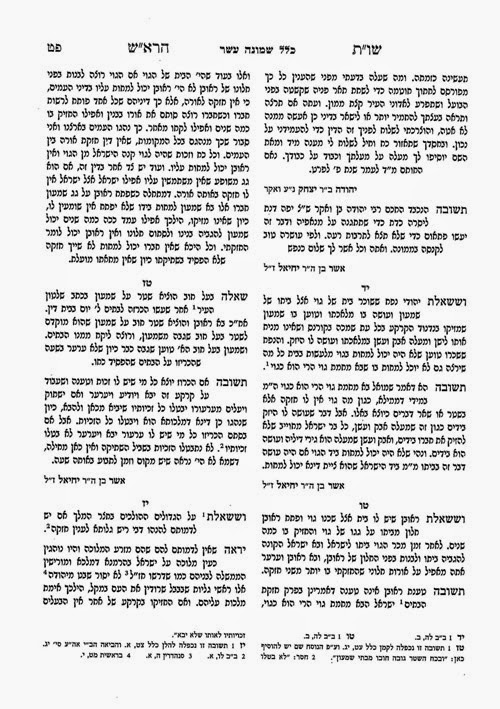

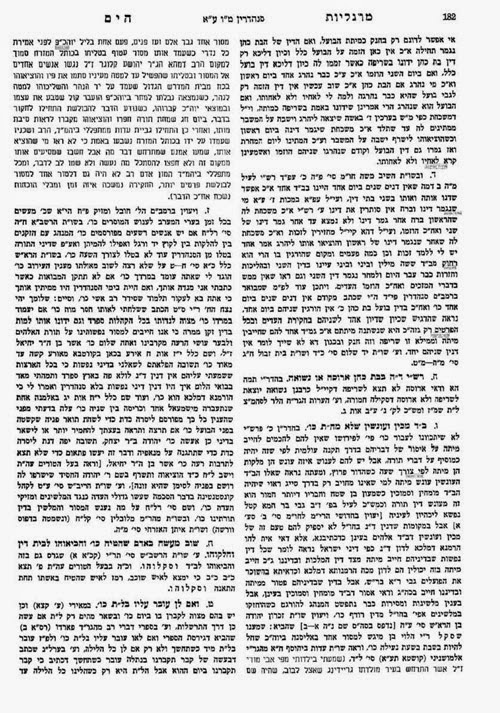

It wasn’t just Saul Berlin who had a problem with this responsum (18:13) of R. Asher. As Zachary Grodzinski pointed out to me, and I later saw that Simhah Assaf makes the same point,[13] in the Vilna 1881 edition of R. Asher’s responsa (also reprinted in Vilna, 1885) the part about cutting of the woman’s nose has been removed. Here is how the responsum looks uncensored, where R. Asher’s questioner writes:

ומה שעלה בדעתי מפני שהענין כל כך מפורסם לחתוך חוטמה כדי לשחת תאר פניה שקשטה בפני הבועל

Here is how the passage looks in the censored edition, which takes out the point about cutting off her nose:

ומה שעלה בדעתי מפני שהענין כל כך מפורסם ליסרה כדת כדי לשחת תאר פניה שקשטה בפני הבועל

The uncensored text above comes from the Machon Yerushalayim edition. What I can’t understand, however, and I think is probably an error (because there is no note), is that the Machon Yerushalayim edition for some reason prints R. Asher’s answer in a censored form.

יפה דנת ליסרה כדת כדי שתתגנה על מנאפיה

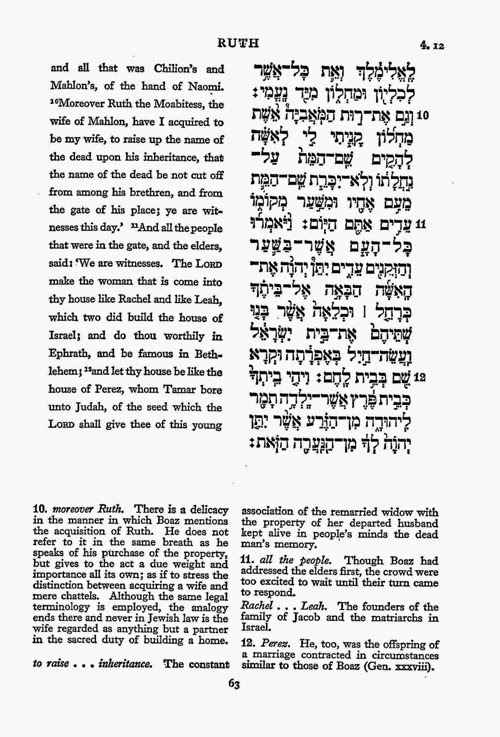

Yet the earlier editions have a more complete answer. Here, for example, is the Venice 1552 edition, which includes the point about cutting off the nose in R. Asher’s answer.

יפה דנת יחתכו חוטמה להשחי’ תאר פניה כדי שתתגנה על מנאפיה

In responsum 17:8 R. Asher recommends cutting out the tongue of a blasphemer. This section of the responsum is also missing from the Vilna edition.[14]

On the matter of physical punishments in Spain,[15] also worthy of note is the responsum in Zikhron Yehudah, no. 75, signed by among others R. Jacob ben Asher, which reports that in Lucena, on the authority of R. Joseph Ibn Migash, an informer was executed (by stoning) on Yom Kippur that fell out on Shabbat during the time of ne’ilah. Since even official executions carried out on authority of the Sanhedrin were not permitted to take place on Shabbat,[16] presumably Ibn Migash decided that in this case there was impending danger from the individual and the execution could not be postponed.[17]

Regarding a different scoundrel, R. Asher stated (17:6):

מותר לנוחרו אפי’ ביוה”כ שחל להיות בשבת

This means that he can be killed on Yom Kippur that falls out on Shabbat.[18] In the Vilna edition the word לענשו is substituted for לנוחרו. The implication of לענשו is that the sinner be punished, but not that he be killed. As we saw with the other example where the Vilna edition made a change, there was obviously a concern by the printer in the Czarist kingdom not to publicize the physical punishments that Jews enforced in medieval Spain.[19]

The language מותר לנוחרו אפילו ביום הכפורים שחל להיות בשבת is taken from Pesahim 49b where it states that an am-ha’aretz may be killed on Yom Kippur that falls out on Shabbat. This is quite a shocking statement, one of a number of strong statements directed against the am ha-aretz,[20] and it certainly is not meant to be taken literally or as referring to what today we call an am ha’aretz.[21] A number of different interpretations have been offered, many of which have their own difficulties. For example, R. Isaac Alfasi, ad loc., explains the passage to mean that he can be killed if he is chasing after a man or an engaged woman to rape them on Yom Kippur.

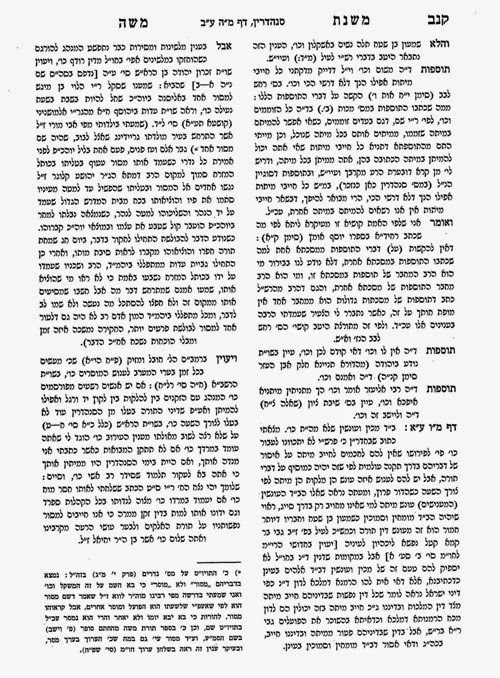

The first problem with this interpretation is that if this is what the passage meant the Talmud could have easily said so, as was pointed out by R. Asher ben Jehiel, ad loc.[22] Furthermore, the presence of an am ha’aretz in this scenario does not add anything, as even if it was a talmid hakham intent on the crime he would be killed. R. Jacob Emden, in his comment, ad loc., as usual has an original perspective in answering this problem. He notes that with regard to a typical rodef, if you can save the endangered person by only injuring the rodef then this is what you must do. However, Emden claims that when dealing with a rodef who is an am ha’aretz, one doesn’t need to be concerned with only injuring him, as you can simply kill the am ha’aretz.

דבסתם רודף אם יכולין להציל לנרדף באחד מאבריו של רודף אין רשאין להרגו, משא”כ בעם הארץ אין חוששין לו כך כך, מאחר שעל חייו אינו חס. אבל באופן אחר חלילה להרגו, דלא גרע מגויים עובדי אלילים דקיי”ל לא מעלים, גרמא בעלמא במניעת הצלה דוקא הוא דשריא, אבל אין מורידין, הריגה בידים אסירא, על אחת כמה וכמה ישראל עם הארץ.

I have no clue what led Emden to this point, which I see as quite shocking, as it legitimates what according to mainstream halakhah would be regarded as an act of murder. (The words of Emden I have just quoted are taken from the Nehardea edition of the Talmud, which uses Emden’s manuscript. The version of Emden’s comment found in the standard Vilna Shas and even in the new Oz ve-Hadar Talmud is a censored text.)

There is another surprising text in Rabad’s Temim Deim,[23] written by the Tosafist R. Isaac bar Samuel. He mentions that informers would be killed even if they only caused monetary damage to the Jewish community. In discussing how this is permitted, he refers to the talmudic passage that states that one can kill an am ha’aretz. R. Isaac explains the matter as follows: There are times when it is pikuah nefesh to kill an am ha’aretz, such as when he is unconcerned with other lives and is suspected of thievery and murder. What is really shocking is that R. Isaac continues by saying that even if you don’t know with certainty that this particular am ha’aretz has committed these crimes, since most of those he associates with are indeed suspected of this, it is permitted to kill the am ha’aretz even when he is not chasing after someone to cause harm!

How can this act be justified? R. Isaac says that perhaps the permission can be derived from a biblical verse, but even if not, he tells us that the Sages have the power to uproot commandments in the Torah, so if we kill the am ha’aretz, it is on their authority and we don’t need to be concerned with the prohibition of murder.

שאמרו רבותינו שיש עם הארץ שמותר לקורעו כדג ומותר לנוחרו ביום הכפורים שחל בשבת. אבל אין תמה דטעמא רבא איכא שפעמים שהוא פקוח לנפש כמה נפשות כגון אותו שידוע שאינו חס על חיי חבירו וחשוד ללסטם ולהרוג כשהוא יכול ואפי’ כשאינו ידוע בו בבירור כיון שרוב העושים כמעשיו הם חשודים בכך מותר ואפי’ שלא בשעת רדיפתו ואפשר שיש שום פסו’ ע”ז ואפי’ אין שם שום פ’ יש כח ביד חכמים לעקור דבר מן התורה ואפי’ בקום עשה דברי הכל כשיש טעם קצת למתיר שאז אינו דומה לעקירה

“The great novelty here is the sweeping heter to kill potential murderers, even if there is no specific knowledge that this particular am ha’aretz is a rodef.”[24] Such a view is not found among any of the other rishonim, and, it need hardly be said, if adopted would have dangerous implications. Had the authors of the controversial Torat ha-Melekh known of this text, they would certainly have cited it. (I will deal with Torat ha-Melekh in a future post.)

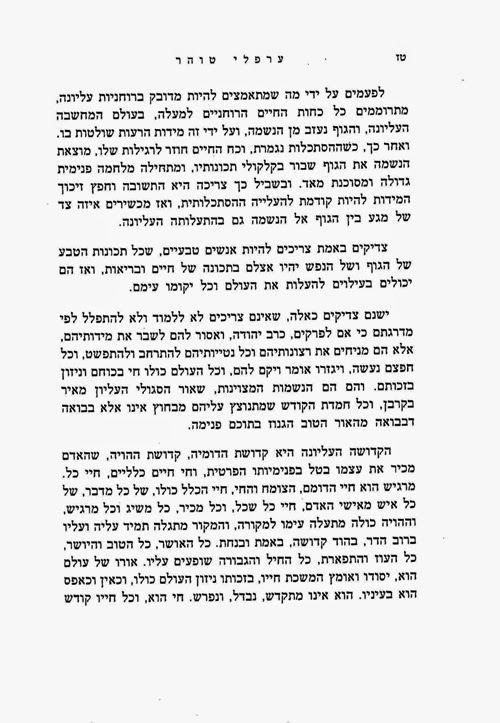

A different perspective is offered by the Maharal. He explains that while it is indeed forbidden to kill an am ha’aretz, he actually deserves to be killed. The only reason he is not killed is because of his potential to become something better than he is. The Maharal, in saying this, is not referring to an ignorant person, what today we call an am ha’aretz. For the Maharal, ignorance is not enough to put one in the same category of those whose existence is not “for the glory of God” and who are “lower than an animal.”[25] The Maharal also cites talmudic opinions that if one merely says the Shema or puts on tefillin or wears tzitzit, he is not to be regarded as an am ha’aretz. According to these views, an am ha’aretz is completely material. Yet one who performs the mitzvot just mentioned shows that he has a spiritual connection, and is thus removed from the category of am ha’aretz.[26]

The idea that an am ha’aretz is killed on Yom Kippur that falls on Shabbat leads to another matter. In the letter against the study of philosophy signed by R. Solomon ben Adret and many others,[27] the following sentence appears.

והספרים ההם אשר עשו ישרפו בשבת לעיניהם

At first glance, what this appears to be saying is that the books of philosophy should be burnt on Shabbat, and some scholars did understand the words in this fashion.[28] This would, however, be problematic, since there is no apparent halakhic justification for burning heretical works on Shabbat. In fact, it has been pointed out that the letter is not speaking about Shabbat at all.[29] It is simply using a melitzah based on the verse in II Sam. 23:7 which reads:

ובאש שרוף ישרפו בשבת

The final word has a kametz under the shin, and a segol under the bet, ba-shavet. The words mean “they shall be utterly burned with fire in their place.” In other words, there is nothing about Shabbat in his verse, or in the letter signed by the Rashba.

Finally, I want to discuss a recent article by Rabbi Shalom C. Spira and Dr. Mark A. Wainberg that appeared in Hakirah entitled “Criminalization of HIV Transmission.”[30] They begin by quoting R. Zvi Spitz who argues that one who knowingly allows his illness to be passed to someone else, under Torah law he is responsible for damages.[31] Therefore, one who knowingly injects another with HIV would be regarded as responsible for the result.

Following this, the authors cite R. J. David Bleich who thinks that according to Torah law one who intentionally injects another with HIV (today we could add Ebola) would not be responsible for damages since in order for actual infection to take place, a series of chemical steps must occur placing the initial injection in the category of gerama. This is a strange position, to say the least, and R. Bleich himself quotes R. Eliezer Waldenberg’s objection to this way of thinking, as it would mean that one who puts poison in another’s drink is not biblically culpable for murder.[32] Since there is a dispute about this matter, Spitz and Wainberg conclude that “Evidently, the principle of “kim li” would serve to exculpate the murderer before a human court.” (pp. 137-138). They further say that one who intentionally injects another with HIV cannot be sued for monetary damages in a Beth Din, “but will instead be responsible before the Heavenly court, as would be the consequence for any gerama.” The one who injected an innocent person with HIV will “bear a supererogatory obligation to voluntarily offer restitution to his victim.”

Although the authors have previously cited R. Spitz as disagreeing with R. Bleich, they nevertheless state that “R. Spitz would probably concede to R. Bleich, simply because it is difficult to envisage a compelling refutation of all the countervailing authorities cited by R. Bleich.” This is a ridiculous statement as R. Spitz’s entire argument is in direct opposition to what R. Bleich states, and he cites the Steipler in support of his position. Where do the authors get the idea that because they are convinced by R. Bleich’s argument that R. Spitz would have to concede?[33] (In general, it is very rare for a halakhic authority debating an issue to concede that he was mistaken in his understanding.)

Finally, the authors note the possibility of the secular government punishing someone who injects another, but their assumption is that from a Jewish standpoint a person can go around injecting others with HIV and not pay any price, neither criminal nor civil, for his actions. If this was indeed the case, then the non-Orthodox community would be absolutely correct in their assumption that Jewish law is completely unsuited for running a modern legal system. However, that is not the case, and the problem is not with Jewish law, but with presentations of the sort just described.

Reading Spira’s and Wainberg’s article, which deals with a real life, contemporary problem, is like reading an article dealing with Jewish criminal law in which it is stressed that there is a need for someone to warn the criminal before he commits his crime as well as an absolute requirement for two male witnesses. Such a hypothetical article would conclude that if someone pulled out a machine gun at a Hadassah convention and killed 30 women, that Jewish law offers no way to punish him, as he was not warned and the action was only observed by women. At best, the author might suggest, as did Spira and Wainberg, that the murderer would be encouraged to “voluntarily offer restitution.”

The fact is that if we had a Jewish state in which Jewish law was the law of the land, the murderer described in the previous paragraph would not get away with it, and neither would the guy who injects another with HIV. As I have already discussed in prior posts, Jewish law allows the authorities vast discretion in order to do what is needed to ensure order and punish wrongdoers.[34] See

here where I quote the Rashba who said that to insist on Torah law in these sorts of matters would “destroy the world.”

So in the real world, in a state run according to Jewish law, if someone purposely injected another with HIV he would not get off scot-free and encouraged to “voluntarily offer restitution,” as stated by Spira and Wainberg. What would happen is that the beit din would sentence the man to jail for attempted murder. In addition, assuming the man had any money, the beit din would confiscate a significant amount of it in order to cover the cost of medication for the man he infected. This is how Jewish law operates, and has always operated, in the real world when Jewish courts have had real authority. Any other portrayal is not only historically incorrect, but does a terrible disservice as it announces to both Jews and non-Jews that Jewish law is not equipped to handle the problems of the real world.

3. A number of people have suggested that I turn my posts into a book. Such a book would have to include many pictures and would be a large size book complete with an index. Since we are dealing with around a thousand pages so far, It would have to be at least two volumes. I think it would take quite a bit of effort to produce the book, which I am willing to do if there is an interest. I wonder how many people would buy such a book when the posts are available for free online. What do you think?

4. I will once again be leading tours this summer to Central Europe, Spain, and Italy. For more information, please go here

http://torahinmotion.org/.

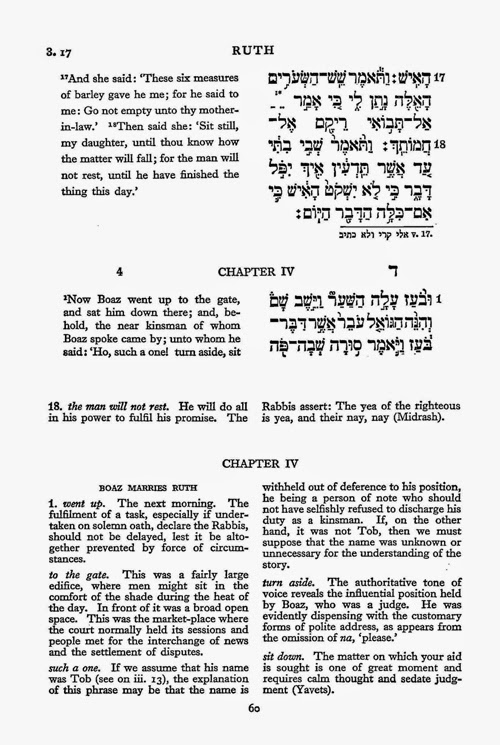

5. The newest work in the series I edit has just appeared: Ephraim Chamiel,

The Middle Way: The Emergence of Modern-Religious Trends in Nineteenth-Century Judaism, Responses to Modernity in the Philosophy of Z. H. Chajes, S. R. Hirsch and S. D. Luzzatto. You can order it by going here

here or calling 617-782-6290. By using the promotion code Chamiel30 Seforim Blog readers can get the volumes at 30% off.