Marc B. Shapiro – Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 3

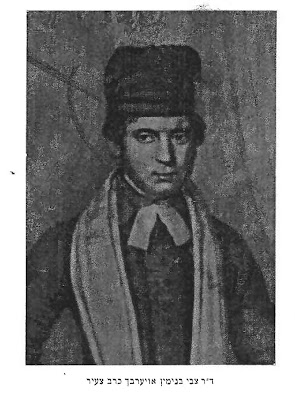

I thought that I had exhausted all I had to say about Rabbi Zvi Benjamin Auerbach’s edition of the Eshkol — see my first two posts at the Seforim blog, here and here [and elaborations] — but thanks to some helpful comments from readers, there is some more material that should be brought to the public’s attention. Even before looking at this, let me express my gratitude to Dan Rabinowitz who sent me this picture of a youthful Auerbach. In my first post I cited R. Yitzhak Ratsaby as a very rare example of a posek who is aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol. A scholar who wishes to remain anonymous, and who has helped me a great deal in the past,[1] called my attention to R. Yehiel Avraham Zilber (the son of R. Binyamin Yehoshua Zilber), who is also aware of the Eshkol problem. In his Berur Halakhah, Yoreh Deah (second series), p. 111, he notes that R. Ovadiah Yosef cites Auerbach’s Eshkol in matters of hilkhot niddah. Yet the authentic Eshkol does not have any section for niddah. In fact, as Yaakov Sussman has pointed out,[2] Auerbach’s Eshkol, vol. 1, p. 117, also refers to the Yerushalmi on Niddah. However, this is impossible as neither R. Abraham ben Isaac nor any of the other rishonim had this volume.

In my first post I cited R. Yitzhak Ratsaby as a very rare example of a posek who is aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol. A scholar who wishes to remain anonymous, and who has helped me a great deal in the past,[1] called my attention to R. Yehiel Avraham Zilber (the son of R. Binyamin Yehoshua Zilber), who is also aware of the Eshkol problem. In his Berur Halakhah, Yoreh Deah (second series), p. 111, he notes that R. Ovadiah Yosef cites Auerbach’s Eshkol in matters of hilkhot niddah. Yet the authentic Eshkol does not have any section for niddah. In fact, as Yaakov Sussman has pointed out,[2] Auerbach’s Eshkol, vol. 1, p. 117, also refers to the Yerushalmi on Niddah. However, this is impossible as neither R. Abraham ben Isaac nor any of the other rishonim had this volume.

Zilber writes that his own approach is not to rely on anything in either Auerbach’s Eshkol or the Nahal Eshkol. In his Berur Halakhah, Orah Hayyim (third series), p. 16, he also states that a certain passage in Auerbach’s Eshkol, Hilkhot Tzitzit cannot be authentic. Before I was alerted to these two sources I had never examined any of Zilber’s volumes (although I have perused the works of his father). Now that I have looked at them I see that they contain a great deal of learning, but my sense is that they are of no significance in the halakhic world, and are rarely quoted.

This doesn’t mean that they are not valuable in and of themselves, but with so many halakhic books being published, only some can make it to the top. The rest, no matter how learned, remain little studied and even less quoted. One must feel bad for authors who put so much effort into producing their works which could be of great use to people, yet at the end of the day do not have any impact.

As Eliezer Brodt has already pointed out, in a previous post at the Seforim blog, with respect to books on hilkhot shemitah, although new volumes continue to appear, it is hard to believe that much of anything original is being added.[3] The same can be said for the laws of Shabbat, where I don’t see how another new book recording the halakhot can possibly have any value as we already have so many fine books in this area. If the author is going to come up with new rulings, then fine, but it is hard to see how the world will benefit from yet another collection of the various melakhot and what is permitted and forbidden.

This doesn’t mean that up-and-coming halakhic scholars have nothing to write about. For example, there is only one book on the halakhic issues involved in sex change operations, so here is an area that cries out for our best and brightest to direct their talents towards. For those who are writing books that are not given the attention due them, one should not lose hope. Occasionally a book that is ignored in its time comes back in a future generation and assumes great popularity (e.g., the Minhat Hinnukh), while books which were very popular in previous years fall out of style. One example of the latter is the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh. When I was young everyone seemed to study it. It has been reprinted numerous times and also translated into many languages. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, it went through fourteen editions in the author’s lifetime, which I think is a record for halakhic works. Yet today, I don’t know anyone who uses it as a work of practical halakhah. (Simply writing this ensures that people will e-mail me to point out that there are indeed some who still use it).

For those who are writing books that are not given the attention due them, one should not lose hope. Occasionally a book that is ignored in its time comes back in a future generation and assumes great popularity (e.g., the Minhat Hinnukh), while books which were very popular in previous years fall out of style. One example of the latter is the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh. When I was young everyone seemed to study it. It has been reprinted numerous times and also translated into many languages. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, it went through fourteen editions in the author’s lifetime, which I think is a record for halakhic works. Yet today, I don’t know anyone who uses it as a work of practical halakhah. (Simply writing this ensures that people will e-mail me to point out that there are indeed some who still use it).

Returning to the anonymous scholar mentioned above, he also alerted me to a letter by R. Michael[4] Aryeh Stiegel which appeared in Tzefunot 1 (Tevet, 5749): 108. In this case I had actually seen the letter, as I own the journal and even have my pen mark on this page. But I had forgotten about it, so once again I am in the anonymous scholar’s debt. Before noting what he says, let me repeat what I mentioned in a previous post, namely, that the publication of the fourth volume of the Eshkol is very strange. We are given no information about the manuscript such as where it came from and why no one, including Auerbach’s family, had ever heard of it until it was published.

There is one other point which I neglected to make in my previous post, but it also is relevant. In 1974 Bernard Bergman published an essay on Auerbach in the Joshua Finkel Festschrift (later included as an appendix to vol. 4 of the Eshkol) in which he defended him against Albeck’s attack. At the time of this essay Bergman knew nothing about any unpublished manuscript of Auerbach’s Eshkol. It is very suspicious, to say the least, that Bergman is also the one to publish the newly discovered volume. Are we supposed to assume that it is just coincidence that Bergman, who earlier had published an essay on Auerbach, discovered this manuscript? (Those who are old enough will recall that during these years Bergman had lots of other things on his mind.) Of course, it is possible that some rare book dealer came into possession of the manuscript and knowing Bergman’s interest in Auerbach, sold it to him. In my previous post I stated that despite the problems that can be raised about the new volume, barring any further evidence we should give Bergman the benefit of the doubt.

Yet Stiegel notes something which should force us to reopen the issue. In volume 4, p. 26 n. 24, we find the following in the Nahal Eshkol.

The problem is that the edition of Ra’avan with R. Solomon Zalman Ehrenreich’s commentary Even Shlomo only appeared in 1926, many years after Auerbach’s death. This sort of anachronism is often what enables scholars to uncover a fraud.

When problems became apparent in Auerbach’s edition, Albeck called for the manuscript to be produced, and this was never done. Here too, I call for the manuscript of volume 4 to be produced, and for the publisher, Machon Harry Fischel, to join in this demand. Only when we can examine the manuscript will we be able to determine what is going on. If the answer given is that the manuscript cannot be located, which was the same answer given one hundred years ago, then the possibility that Eshkol volume 4 is a late twentieth century forgery will have to be seriously considered.

The anonymous scholar also alerted me to R. Hayyim Krauss’ Toharat ha-Shabbat ke-Hilkhatah. Krauss is known for a campaign he mounted in the 1970’s, culminating in the publication of his books Birkhot ha-Hayyim and Mekhalkel Hayim be-Hesed, which were in large part devoted to showing that the proper – and original — pronunciation in the Amidah is morid ha-geshem, not gashem. There is no doubt that Kraus was correct, but I don’t know if his campaign bore any fruit. Certainly in the United States when I was growing up, virtually everyone said gashem since that is what the siddurim had, including Brinbaum. Matters have changed greatly in the last twenty years because of the ArtScroll siddur. This siddur vocalizes – or, to use the word that ArtScroll prefers, “vowelizes” – גשם as geshem. I have previously noted one example where the Artscroll siddur has changed the davening practices of the American Orthodox community[5] and this is another. Had the ArtScroll siddur given gashem as the pronunciation, that’s what we all would be saying now.

Since this blog is devoted to seforim, with a great focus on bibliographical curiosities, let me mention the following: It has been awhile since I’ve seen the literature about geshem vs. gashem, but I remember that the side that supported gashem was able to show that it was not only grammarians who supported this reading, but R. David Lida (c. 1650-1696) Ashkenazi rav of Amsterdam, also attested to it. In fact, he might be the earliest authority to do so. But those who cited Lida didn’t know a couple of things about him. Neither do the people who keep publishing his works. To begin with, Lida was a plagiarizer, and not a very skilled one at that.[6]

People can live with plagiarism, especially as it is not uncommon in haredi “mehkar.”[7] But worse, much worse, is that Lida also appears to have been a Sabbatian. In my Limits of Orthodox Theology, p. 42 n. 21, I called attention to something similar. The Yemenite kabbalists who attacked R. Yihye Kafih made use of, and defended, a Sabbatian work written by Nehemiah Hayon. It was only after R. Kook pointed out the true nature of Hayon’s work that they excised this defense. As I commented in my book, this shows the elasticity of apologetics, in that if one beleves a work is “kosher,” he will devote great efforts to defending it, but after learning that the author is a Sabbatian the defense is immediately dropped. We must ask, however, why were the ideas in this work acceptable before the author’s biography was known?

Returning to Krauss’ Toharat ha-Shabbat ke-Hilkhatah, in volume 1 of this work he cites Auerbach’s Eshkol. In volume 2, p. 450, Krauss publishes a letter he received from R. David Zvi Hillman. Hillman, in addition to being an outstanding talmid hakham, also has a real historical sense and many years ago edited Iggerot ha-Tanya u-Venei Doro (Jerusalem, 1953). In more recent years he published an interesting, though wrong-headed, article arguing that Meiri’s views of anti-Gentile halakhot are not to be taken seriously but were written due to fear of the censor (which was a concern even in pre-printing days).[8] He has also been involved with the Frankel edition of the Rambam, most recently editing Sefer ha-Mitzvot. Despite its problems, the Frankel edition of the Mishneh Torah is now the standard edition for both yeshivot and the academic world.[9]

As everyone knows, the Frankel edition has been attacked for systematically ignoring the writings of some prominent non-haredi gedolim. For example, there are no references to R. Kook, even though he wrote a commentary on the Rambam’s shemitah laws, which will be mentioned in an upcoming post at the Seforim blog. (He is cited the ArtScroll Mishnah volume on Shevi’it.) It was because of this affront that R. Kook’s followers have put out a separate index of commentaries on the Mishneh Torah, which is now available online. See here.

A particularly harsh criticism of the Frankel edition, which appeared as an “open letter,” is found here:

Hillman chose to answer this critique. He briefly mentions the issue of R. Kook, but has a lot to say about R. Kafih, and his critique of the latter is incredibly sharp. Here is his letter:

Hillman chose to answer this critique. He briefly mentions the issue of R. Kook, but has a lot to say about R. Kafih, and his critique of the latter is incredibly sharp. Here is his letter:

Even if one doesn’t agree with him, it should be obvious to all that Hillman has a much broader knowledge than the typical talmid hakham. It therefore should not be surprising that he was critical of Krauss for including Auerbach’s Eshkol. In fact, Krauss does not even print Hillman’s entire letter, but cuts out a section that no doubt would have been seen as disrespectful to Auerbach. Thus, Hillman writes:

Even if one doesn’t agree with him, it should be obvious to all that Hillman has a much broader knowledge than the typical talmid hakham. It therefore should not be surprising that he was critical of Krauss for including Auerbach’s Eshkol. In fact, Krauss does not even print Hillman’s entire letter, but cuts out a section that no doubt would have been seen as disrespectful to Auerbach. Thus, Hillman writes:

The second ellipsis was inserted by Krauss. In his letter Hillman must have written, “Even if you want to say that Auerbach didn’t forge this section, and it really was stated by the Eshkol.” Yet Krauss didn’t want anything negative about Auerbach to appear in print, so he cut it out. Hillman also calls attention to the comments of R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira in the introduction to his Darkhei Teshuvah on hilkhot mikvaot. Here Shapira notes that the Maharsham cited Auerbach’s Eshkol, and this once again raises the problem I have earlier discussed, namely, what to do with pesakim that rely on forged texts? (This is not such a problem in hilkhot mikvaot, as Shapira notes that most of what is quoted from Auerbach’s Eshkol is le-humra).

Shapira states that he is not prepared to decide the matter of the authenticity of Auerbach’s Eshkol, yet according to Hillman נראה מכתלי דבריו שדעתו נוטה לצד המערערים על אמיתותו. It is obvious that the reason Shapira does not definitively decide the matter is because of his feeling of respect for Auerbach as a great talmid hakham. The notion that such an outstanding Torah scholar, one of the German rabbinic elite, could perpetrate such a fraud is difficult for people to accept. Yet Shapira is also surprised that the Maharsham cites Auerbach’s Eshkol entirely oblivious to the problems with this edition.

I don’t see this as unusual at all. Shapira was an incredibly learned man, with knowledge of all sorts of things, but the Maharsham was an ish halakah whose life was spent in Shas and Poskim. Similarly, although R. Moshe Feinstein quotes Auerbach’s Eshkol, I would assume that he too had never heard of the controversy, as it is not something that penetrated the walls of the traditional Lithuanian Beit Midrash (at least not until so many bachurim began reading the Seforim blog!). Shapira writes:

In his reply to Hillman, Krauss states that he was indeed aware of the problems with Auerbach’s Eshkol, and even referred to Shapira’s introduction, but he did not want to elaborate (and indeed, he never quotes what Shapira says, but only tells the reader to examine it). I think that many people in the traditional world who know about the issue have this problem as well. They are between a rock and a hard place. If they say nothing, then a forgery is allowed to remain part of the Torah world. Yet if they write against it, they must take on someone who in his lifetime was recognized as one of the gedolim of Germany. Like all gedolim, he was also regarded as a great tzaddik.

Krauss does allow himself to say the following:

Prof. Yaakov Spiegel has also called my attention to his article in the latest Sidra[10] focusing on the various terms used for describing the blessing of the new moon. It so happens that in medieval times the term kiddush levanah was not found in either the Sephardic world or among Provencal scholars. Yet as Spiegel notes, this expression is found in Auerbach’s Eshkol, in a section that is missing from Albeck’s edition. This is another proof (if any was needed) that Auerbach’s edition is a forgery.[11]

The Auerbach forgery relates to another issue, that of rabbis lying and making things up for what they view as good reasons (which ties into my current project on censorship). Let me offer one example of this, but first I must give some background. If there is one thing Orthodox Jews know it is that sturgeon is a non-kosher fish. Yet as with so much else that people know, this is not exactly correct. While our practice today is not to eat sturgeon, no less a figure than the great R. Yehezkel Landau, the Noda bi-Yehudah, permitted it.[12] This decision led to enormous controversy as many of the greatest rabbis of Europe lined up in opposition.

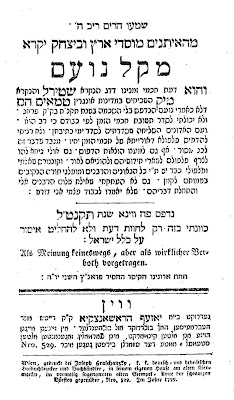

Rabbi Aaron Chorin, at this time rav of Arad, Hungary, was a student of R. Yehezkel and he took up the cause of kosher sturgeon, publishing the volume Imrei Noam (Prague 1798) in support of his teacher’s view. At this time he had not yet crossed over to the dark side where he would, in the Hatam Sofer’s words, become known as אחר, an abbreviation of the way Chorin signed his name: Aron Choriner Rabbiner (see Teshuvot Hatam Sofer, 6:96). R. Isaac Grishaber, the rav of Paks, took up the battle against Chorin and published the volume Makel Noam (Vienna 1799). Here is the title page of the book: Chorin responded with another book on the subject, Shiryon Kaskasim (Prague, 1800).

Chorin responded with another book on the subject, Shiryon Kaskasim (Prague, 1800).

Grishaber was a fairly well known rabbi, and in recent years Torah journals have begun to print his unpublished writings. The problem that Grishaber was up against was that even with the many rabbis who wrote haskamot for his book, the great R. Yehezkel Landau had ruled differently. How could he destroy Chorin’s argument, convince the people that he was right, and most importantly, spare Jews from eating non-kosher when the recently deceased gadol ha-dor stood in his way?

Even before Chorin published his book, Grishaber had been on a crusade to have sturgeon declared as non-kosher. As part of this battle Grishaber took a fateful step which I have no doubt was done le-shem shamayim, but which from our perspective must be regarded as reprehensible.

In his effort to stop the eating of sturgeon, which he firmly believed was a terrible sin, Grishaber declared that R. Yehezkel sent him a letter retracting his decision and asking him to forward this letter to the rabbi of Temesvar, to whom he originally gave his lenient opinion. Grishaber states that the original letter of R. Yehezkel, which he received and sent on to the other rabbi, was lost in the mail.[13] He also writes that he misplaced the copy he made of R. Yehezkel’s original letter to him. This is all very fishy. Not surprisingly, R. Yehezkel’s son, R. Samuel, and R. Yehezkel’s leading student, R. Eleazar Fleckeles, rejected Grishaber’s testimony. They declared that he never received such a letter. In other words, he was lying when he stated that the Noda bi-Yehudah had retracted his opinion.

These are strong words, but it is hard to read what R. Samuel and R. Fleckeles write and still have any doubts that Grishaber was engaging in a fraud – although as R. Samuel states, Grishaber no doubt believed that in the effort to stop people from eating non-kosher even this was permissible. Here are some of R. Samuel’s words (Noda bi-Yehudah, Yoreh Deah, tinyana, no. 29), which are very interesting in that he keeps the standard respectful phrases at the same time that he is telling Grishaber that he is a liar.

Grishaber also had to deal with the fact that in Turkey the Jews ate sturgeon. To this he replied that one could not rely on the Turkish Jews since many of them were still followers of Shabbetai Zvi. R. Samuel had no patience for this nonsensical assertion.

Fleckeles also speaks harshly (Teshuvah me-Ahavah, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 329), and this comes after beginning his letter with all the customary rabbinic introductory words of praise.

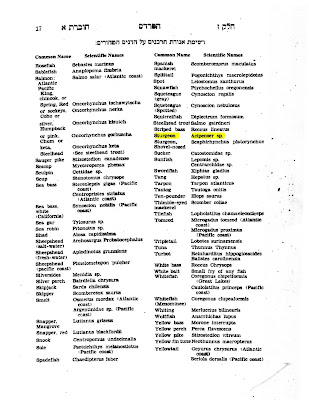

Although there were some who supported R. Yehezkel, this remained a minority opinion. By now no one is in dispute about this matter. Yet I wonder if any readers recall eating sturgeon in the United States. I ask because there was a time when sturgeon was regarded as kosher in this country. Here is a page from the list of kosher fish published by Agudas ha-Rabbonim in Ha-Pardes, April 1933. This advertisement for delicious sturgeon appeared in subsequent issues of Ha-Pardes.

This advertisement for delicious sturgeon appeared in subsequent issues of Ha-Pardes.

1. The Chief Rabbinate of Israel declared swordfish to be kosher, and in a 1960 responsum R. Isser Yehudah Unterman defended this ruling. In response to R. Moshe Tendler’s objection, Unterman reaffirmed its kosher status.[14] It is likely that the widespread assumption that swordfish is not kosher can be traced to Tendler’s successful efforts in this regard. Today, who even remembers the that swordfish used to be kosher?

2. There was a great rav in Boston named Mordechai Savitsky. To a certain extent he was an adversary of the Rav and was one those tragic figures in American Orthodoxy. His Torah knowledge was the equal of any of the outstanding Roshei Yeshiva who became so popular, but he was never able to find his place. He publicly declared – and in his Shabbat ha-Gadol derashah no less – that swordfish is kosher.

These two points are enough to show that the issue of swordfish is anything but settled, and is certainly not an Orthodox-Conservative issue. Zivotofsky’s article will be quite illuminating in this regard.

Notes:

[1] See The Limits of Orthodox Theology, Preface.

[2] Mehkerei Talmud 2 (1993), 255 n. 196.

[3]”R. Yaakov Lipshitz and Heter Mechirah,” the Seforim blog (October 11, 2007), available here.

[4] In an effort to keep far away from non-Jewish names, many people who are named מיכאל spell it as Michoel. I have even seen Mecheol. Certainly, no one today in the haredi world who has the name משה would write his English name as Moses, as is found on R. Moshe Feinstein’s stationery.

[5] See here at note 8.

[6] See Bazalel Naor, Post-Sabbatian Sabbatianism: Study of an Underground Messianic Movement (Spring Valley, 1999), 38; Marvin Heller, “David ben Aryeh Leib of Lida and his Migdal David: Accusations of Plagiarism in Eighteenth Century Amsterdam,” Shofar 19 (Winter 2001): 117-128.

[7] Yet can they live with a well-known contemporary rabbi who not only falsified a book he worked on, but has ignored a series of summons to a beit din? See here (and here) for more. Since the censorship and forgery he engaged in are directed against Chabad, it is possible that in his mind he has done no wrong. He probably also assumes that a Chabad beit din is not valid, and therefore he can ignore it.

[8] “Leshonot ha-Meiri she-Nikhtevu li-Teshuvat ha-Minim,” Tzefunot 1 (5749): 65-72.

[9] In my forthcoming book, Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters (University of Scranton, 2008), I give examples of some of the problems. The book should appear in another few months.

[10] “Le-Mashmaut ha-Bituyim: Kiddush Hodesh, Birkat Levanah, Kiddush Levanah,” Sidra 22 (2007): 185-200.

[11] For other forgeries in Auerbach’s Eshkol, see Louis Ginzberg, Perushim ve-Hiddushim Birushalmi, vol. 1, Introduction, p. 84, and vol. 4, p. 6. I owe these references to the anonymous scholar.

[12] Noda bi-Yehudah, Yoreh Deah, tinyana, no. 28.

[13] See Yisrael Natan Heschel, “Mismakhim Nosafim le-Folmos Dag ha-Stirel bi-Shenat 5558,” Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael (Sivan-Tamuz 5755): 109.

[14] See Shevet mi-Yehudah, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 5.