Benefits of the Internet: Besamim Rosh and its History

By: Dan Rabinowitz & Eliezer Brodt

In a new series we wanted to highlight how much important material is now available online. This, first post, illustrates the proliferation of online materials with regard to the controversy surrounding the work Besamim Rosh (“BR”).

[We must note at the outset that recently a program has been designed by Moshe Koppel which enables one, via various mathematical algorithims, to identify documents authored by the same author. We hope, using this program, to provide a future update that will show what this program can demonstrate regarding the authorship of the BR and if indeed the Rosh authored these responsa.]

Background

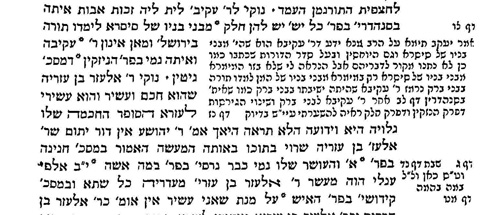

Before turning to the BR and discussing its history we need to first discuss another work. R. Raphael Cohen the chief rabbi of triple community, Altona-Hamburg-Wansbeck (“AH”W”), [1] published a book,

Torat Yekuseil, Amsterdam, 1772 regarding the laws of

Yoreh Deah.

Torat Yekuseil is a standard commentary and is unremarkable when compared to other works of this genre. While the book is unremarkable in and of itself, what followed is rather remarkable.

Some years later, in 1789, a work with the putative author listed listed as Ovadiah bar Barukh and titled

Mitzpeh Yokteil [2] was published to counter R. Raphael Cohen’s

Torat Yekuseil (“TY”)

. Mitzpeh Yokteil (“MY”), was a vicious attack both against the work TY as well as its author, R. Raphael Cohen. R. Raphael Cohen was a well-known and well-respected Rabbi. In fact, he was the Chief Rabbi of the triple community of AH”W. The attack against him and his work did not go unanswered. Indeed, the

beit din of Altona-Wansbeck placed the putative author, Ovadiah, and his work, under a ban.

The Altona-Wansbeck beit din could not limit the ban to just Altona-Wansbeck as the attack in the MY was intended to embarrass R. Raphael Cohen across Europe. Indeed, the end of the introduction to MY indicates that copies were sent to a list of thirteen prominent rabbis across Europe. Specifically, copies were sent to the Chief Rabbis of Prague, Amsterdam, Frankfort A.M., Hanover, Bresslau, Gloga, Lissa, etc., “as well as The Universally Know Goan haHassid R. Eliyahu from Vilna.” Thus, the intent of the book was to diminish R. Raphael Cohen’s standing amongst his peers.

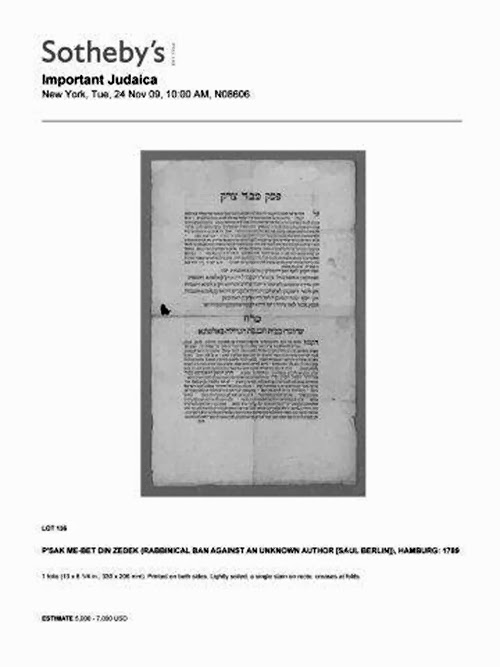

The Altona-Wansbeck

beit din, recognizing the intent of the book, appealed to other cities courts to similarly ban the author and book MY – the ban, entitled,

Pesak mi-Beit Din Tzedek, the only known extant copy was recently sold at Sotheby’s (

Important Judaica, Nov. 24, 2009, lot 136).[3]

These concerns lead the ban’s proponents to the Chief Rabbi of Berlin, R. Tzvi Hirsch Berlin, and to solicit him to join the ban. Initially, it appeared that R. Tzvi Hirsch would go along with the ban. But, as he was nearing deciding in favor of signing the ban, someone whispered in his ear the verse in Kings 2, 6:5, אהה אדני והוא שאול – which R. Tzvi Hirsch understood to be a play on the word “שאול” in the context of the verse meaning borrow, but, in this case, to be a reference to his son, Saul. That is, the real author of MY was Saul Berlin, Tzvi Hirsch’s son. Needless to say, R. Tzvi Hirsch did not sign the ban. [4]

Not only did he not sign the ban, he also came to his son’s defense. Aside from the various bans that were issued, a small pamphlet of ten pages, lacking a title page, was printed against MY and Saul. [5] Saul decided that he must respond to these attacks. He published Teshuvot ha-Rav. . . Saul le-haRav [] Moshe Yetz,[6] which also includes a responsum from R. Tzvi Hirsch, Saul’s father. Saul defends himself arguing that rabbinic disagreement, in very strong terms, has a long history. Thus, a ban is wholly inappropriate in the present case.

R. Tzvi Hirsch explained that while MY disagreed with R. Cohen, there is nothing wrong with doing so. The author of MY, as a rabbi – Saul was, at the time, Chief Rabbi of Frankfort – Saul is entitled to disagree with other rabbis. Of course, Saul’s name is never explicitly mentioned. Moreover, in the course of R. Tzvi Hirsch’s defense he solicits the opinions of other rabbis, including R. Ezekiel Landau. R. Landau, as well as others, noted that aside from the propriety of disagreement within Judaism, the power of any one particular beit din is limited by geography. Thus, the Altona-Wansbeck’s beit din‘s power is limited to placing residents of Hamburg under a ban but not residents of Berlin, including R. Saul Berlin, the author of MY.[7]

The controversy surrounding the MY was not limited to Jewish audiences. The theater critic, H.W. Seyfried, published in his German newspaper,

Chronik von Berlin, translations of the relevant documents and provided updates on the controversy. Seyfried agitated on behalf of the

maskilim and editorlized that the Danish government should take actions against R. Cohen. It appears, however, that Seyfried’s pleas were not acted upon.[8]

The Publication of Besamim Rosh

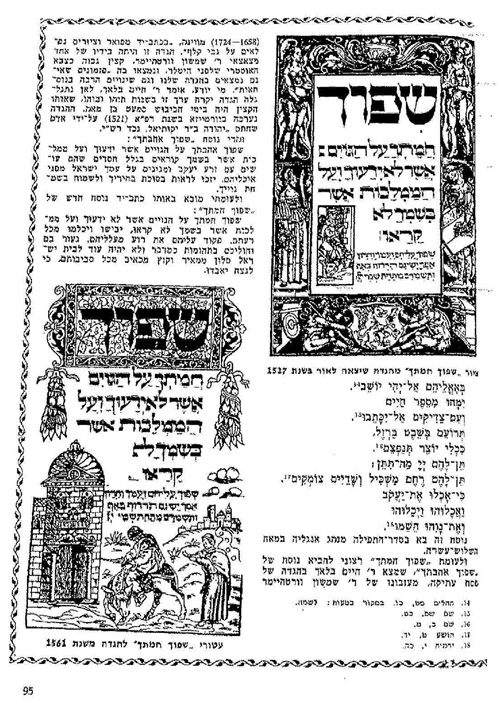

With this background in mind, we can now turn to the Besamim Rosh. Prior to publishing the full BR, in 1792, Saul Berlin published examples of the responsa and commentary found in the BR – a prospectus, Arugat ha-Bosem. This small work whose purpose was to solicit subscribers for the ultimate publication of BR. It appears that while Saul may have been trying for significant rabbinic support, the majority of his sponsors were householders.

In 1793, the BR was published. The BR contains 392 responsa (besamim equals 392) from either R. Asher b. Yeheil (Rosh) (1259-1327) or his contemporaries. This manuscript belonged to R. Yitzhak di Molina who lived during the same time period as R. Yosef Karo, the author of Shulchan Orakh. Additionally, Saul appended a commentary of his own to these responsa, Kasa de-Harshana.

The BR contains two approbations, one from R. Tzvi Hirsch Berlin and the other from R. Yehezkel Landau. R. Landau’s approbation first explains that Rosh’s responsa need no approbation. With regard to R. Saul Berlin’s commentary, he too doesn’t need an approbation according to R. Landau. This is so because R. Saul’s reputation is well-known. R. Landau’s rationale, R. Saul’s fame, appears a bit odd in light of the fact that among some (many?) R. Saul’s reputation was very poor due to the MY.

R. Tzvi Hirsch’s approbation also contains an interesting assertion. Saul’s father explains that this book should put to rest any lingering question regarding his son.

In addition to the approbations there are two introductions, one from di Molina and the other from Saul. Di Molina explained the tortured journey of the manuscript. He explains that, while in Alexandria, he saw a pile of manuscripts that contained many responsa from Rosh that had never before been published. He culled the unpublished ones and copied and collected them in this collection. What is worthy of noting is that throughout the introduction di Molina repeatedly asks “how does the reader know these responsa are genuinely from Rosh.”

R. Saul, in his introduction, first notes that the concept of including introductions is an invention long after Rosh, and is not found amongst any of the Rishonim.

As mentioned previously, the BR is a collection of 392 responsa mostly from Rosh or his contemporaries. Additionally, R. Saul wrote his own commentary on these responsa, Kasa diHarshena. [9] This commentary would contain the first problem for Saul and the BR. In responsum 40, Rosh discusses the position of Rabbenu Tam with regard to shaving during the intermediate days (ho ha-moad). While Rosh ultimately concludes that one is prohibited from shaving on hol ha-moad, R. Saul, in his commentary, however, concludes that shaving on hol ha-moad is permissible. In so holding, R. Saul recognized that this position disagreed with that of his father. Almost immediately after publication, R. Saul printed a retraction regarding this position allowing for shaving on hol ha-mo’ad. This retraction, Mo’dah Rabba, explains that Saul failed to apprise his father of this position and, as Saul’s father still stands behind his negative position, Saul therefore retracts his lenient position. [Historically, this is not the only time a father and son disagreed about shaving on hol ha-moad. R. Yitzhak Shmuel Reggio (YaSHaR)and his father, Abraham, disagreed on the topic as well. As was the case with Saul and his father, the son, YaSHaR took the lenient position and his father the stringent. Not only did they disagree, after YaSHaR published his book explaining his theory, his father attacked him in an anonymous response. For more on this controversy see Meir Benayahu, Shaving on the Intermediary Days of the Festival, Jerusalem, 1995.]

This retraction, while may be interperated as evidence of Saul humbleness in his willingness to admit error and not stand on ceremony, others used this retraction against him. The first work published that questioned the legitimacy of BR is Ze’ev Yetrof, Frankfort d’Oder, 1793, by R. Ze’ev Wolf son of Shlomo Zalman. (This book is very rare and, to my knowledge, is not online. Although not online, a copy is available in microfiche as part of the collection of books from the JTS Library, and on Otzar Hachomah see below) The author explains that eight responsa in BR are problematic because they reach conclusion that appear to run counter to accepted halahik norms. In addition, the author states in his introduction, “that already we see that there is something fishy as it is known that the author [Saul Berlin] has retracted his position regarding shaving.” It should be noted that no where does R. Ze’ev Wolf challenge the authenticity of the manuscript for internal reasons – it is incorrectly dated, incorrectly attributed etc. Apparently, Ze’ev Yetrof, was not well-known as it is not cited by other contemporaries who too doubted the authenticity of BR. Samat theorizes that either wasn’t printed until later or, was destroyed.[10]

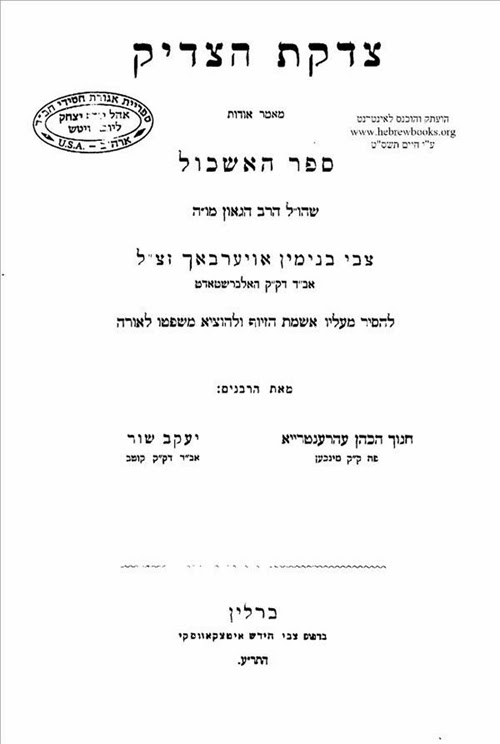

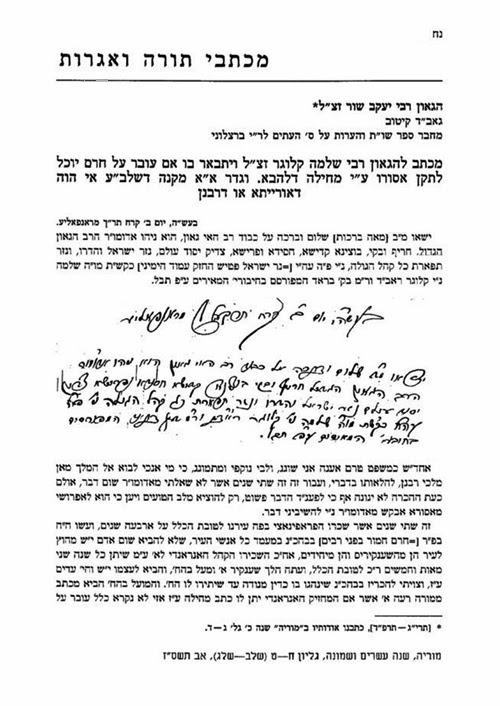

The second person to question the legitimacy of BR was R. Rafael Hamburg’s mechutan, R. Ya’akov Katzenellenbogen. In particular, he wrote to R. Cohen’s student, R. Mordechai Benat. As was the case with Wolf, R. Katzenellenbogen located 13 responsa where he disagreed with the conclusions. R. Katzenellenbogen indicated that R. Benet shold review the BR himself and apprise R. Katzenellenbogen regarding R. Benet’s conclusions.

R. Katzenellenbogen also wrote to Saul’s father, Tzvi Hirsch, and Tzvi Hirsch eventually responded in a small pamphlet. R. Tzvi Hirsch first deals with the predicate question, is the manuscript legitimate. That is, prior to discussing the conclusions of particular responsum, regarding the manuscript, R. Tzvi Hirsch testifies that he is intimately familiar with this manuscript. He explains that for 11 years, the manuscript was in his house. In fact, R. Tzvi Hirsch created the index that appears in BR from this manuscript. Additionally, he had his other son Hirschel (eventual Chief Rabbi of London) copy the manuscript for publication. Thus, R. Tzvi Hirsch argues that should put to rest any doubt regarding the authenticity of the manuscript.

R. Tzvi Hirsch then turns to the issue regarding conclusions of some of the responsa. He first notes, that at most, there are a but a small number of questionable responsa. Indeed, it is at most approximately 5% of the total responsa in BR. That is, no one questions 95% of the responsa (at least not then). Second, with regard to the conclusions themselves, that some conclusions are different than the halahik norms, that can be found in numerous books, none of which anyone questions their authenticity. Thus, conclusions prove nothing.

Leaving the history and turning to the content of BR. One of the more controversial responsa is the one discussing suicide. In particular, according to the responsum attributed to Rosh, the historic practices that were applied to a suicide – lack of Jewish burial, no mourning customs – are not applicable any longer. This is so, because suicides can be attributed to the poor conditions of the Jews and not philosophical reasons. Thus, we can attribute the motivations of a suicide to depression and remove the restrictions that applied to suicides.

This responsum was what lead some, including R. Moshe Sofer (Hatam Sofer), to conclude that the entire BR was a forgery. Indeed, this responsum was one of the two that were removed in the second edition. Others, however, point out this responsum and its conclusions are not in any conflict with any accepted halakhic norms. And, instead, while providing new insight into the current motivations of a suicide, the ultimate conclusion can be reconciled with all relevant laws. [11]

This particular example illustrates the problematic nature of merely relying upon a particular conclusion to demonstrate the authenticity or lack thereof of a work. Although R. Sofer was certain this responsum ran counter to a statement of the Talmud, others were easily able to reconcile the Talmudic statement with the conclusion of the responsum.

Another controversial responsa deals with someone who is stuck on the highway as the Shabbat is fast approaching. The traveler is thus faced with the following dilemma, stop in a city where he will require the charity of strangers or continue on and get home. The BR rules that the traveller can continue and is not required to resort to charity. This, like the responum above, was similarly removed from the second edition. These are the only two responsa removed from the second edition. Of course, this removal isn’t noted anywhere except that the numbers skip over those two. In fact, the index retains the listing for the two responsa.

Other controversial responsa include one dealing with belief in the afterlife and messianic era, kitnoyot – BR would abolish the custom, and issues relating to mikvah.

Today, common practice regarding suicide appears, for the most part, to conform with the position of BR.

Status Today

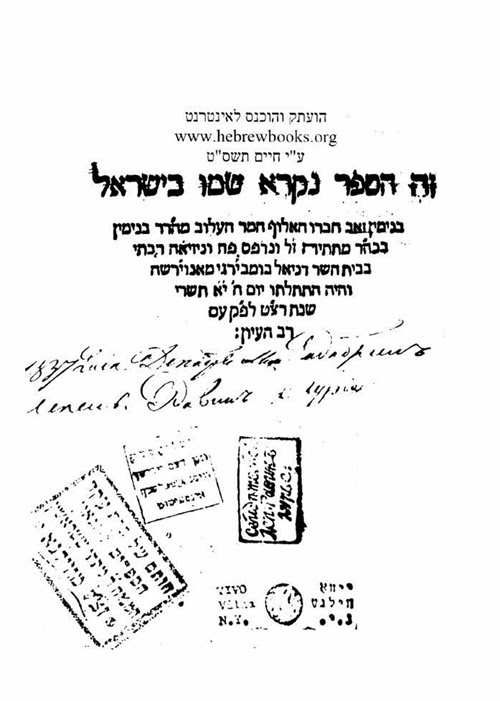

After its publication in 1793, it would be almost one hundred years before the BR would be reprinted. In 1881, the BR was reprinted in Cracow. This edition was published by “the well-known Rabbi Yosef Lazer from Tarnow'” R. Lazer’s was part of a well-known Hassidic family. His grandfather, R. Menachem Mendel Lazer was the author of

Sova Semochot, Zolkiov, 1845.[12] It appears that the BR was the only controversial book that R. Yosef Lazer published. Although he published approximately 30 books, the are mainly run-of-the mill works,

Machzorim,

haggadot, as well as some standard rabbinic works. It is unclear what prompted R. Lazer to republish the BR. Lazer provides no explanation. Although Lazer’s publishing activities are difficult to reconcile with his publication of the BR, the printers, Yosef Fischer and Saul Deutscher, other publications indicate that they were more open to printing all types of books. For example, the same year they published BR, they published a translation of Kant,

Me-Ko’ach ha-Nefesh, Cracow, 1881. In all events, it appears that Lazer (or perhaps the printers) was aware of the controversy surrounding the BR as he removed Saul Berlin’s introduction as well as two of the more controversial responsa, one discussing suicide and the other allowing one to continue to travel home after sunset on Friday to avoid having to rely upon the charity of strangers. In addition, one responsa was accidentally placed at the end of the volume, not in its proper order.[13] Although the two responsa were removed in the text, they still appear in the index. A photo-mechanical reproduction of this edition was published in New York in 1970, and a copy is available on Hebrewbooks.

In 1984, the BR was reprinted for only the third time. This edition, edited by R. Reuven Amar and includes an extensive introduction, Kuntres Yafe le-Besamim, about BR. Additionally, commentary on the BR by various rabbis is included. The text of this edition is a photo-mechanical reproduction of the first edition. This edition contains two approbations, one from R. Ovadiah Yosef, who in his responsa accepts that BR is a product of R. Saul Berlin, but R. Yosef holds that doesn’t diminish the BR’s value. The second approbation is from R. Benyamin Silber. But, R. Silber provides notes in the back of this edition and explains that he holds the BR is a forgery and that he remains unconvinced of Amar’s arguments to the contrary.

In his introduction, Amar attempts to rehabilitate the BR. Initially, it should be noted that Amar relies heavily upon Samet’s articles on BR, but never once cites him. Samet had complied a bibliography of works about BR as well as where the BR is cited, Amar also provides the latter in a sixty four page

Kuntres, ריח בשבמים, in the back of his edition. In his introduction Amar relates the history of the BR and attempts to demonstrate that many accepted the BR and those that did not, Amar argues that many really did accept BR. This introduction contains some very basic errors, many of which have been pointed out by

Shmuel Ashkenazi in his notes that appear after the introduction.

Difficulties in Authentication

Today, various theories have been put forth to demonstrate that the BR is a forgery. Specifically, some have pointed to “hints” or “clues” that R. Saul left for the careful reader which would indicate that BR is a carefully created forgery. For example, some note that the number of responsa, 392, the Hebrew representation of that number is שצ”ב which can be read to be an abbreviation of Saul’s name –

Saul

ben

Tzvi. Others take this one step further and point to the was R. Asher (Rosh) is referenced – רא”ש – which again can be read

R. Saul. Obviously, these clues are by no means conclusive. In the academic world, the BR is written off as a “trojan horse” intended to surreptitiously get R. Saul’s masklik positions out in the masses or something similar. All of these positions, however, rely upon a handful of responsa at best and no one has been able to conclusively demonstrate that the entirety of BR is a forgery. At best, we are still left with the original criticisms – that a few of the responsa’s conclusions espouse positions that appear to be more 18th century in nature than 13th century. [14]

R. Yeruchum Fischel Perlow aptly sums up much of what has been written regarding the question of authenticity of BR:

Just about all who have examined [the question of the authenticity of BR] walk around like the blind in the dark, and even after all their long-winded essays, they are left with only their personal feelings about the BR without ever adducing any substantive proofs in support of their position. And, on the rare occasions that they actual do provide proofs for their positions, it only takes a cursory examination to determine that their is nothing behind those proofs. [R. Yeruchum Fischel Perlow, “Regarding the book ‘Besamim Rosh,'” Noam 2 (1959), p. 317. For some reason this article is lacking in some editions of Noam]

Assuming that one discounts the testimony of Saul and his father regarding the manuscript, it is not easy to determine if the BR is authentic or not. For example, responsum 192, according to R. Moshe Hazan, one of the defenders of BR, this responsum “is clear to anyone who is familiar with the language and style of the Rishonim, from the Rishonim.” Responsum 192, is attributed to R. Shlomo ben Aderet (Rashba), and discusses the opinion of Rosh that allowed for capital punishment for pregnancy out of wedlock. Thus, according to R. Hazan, 192 is conclusive proof that BR is authentic.

Simcha Assaf, however, has shown that responsum 192 is a forgery – or there is a misattribution. Assaf explains that if one looks at the date of this incident, responsum 192 could not have been written by Rashba. Rashba died 10 years prior to this event. Simcha Assaf,

Ha-Onshim Ahrei Hatemat ha-Talmud, Jerusalem, 1928, pp. 69-70. Thus, the very same responsum whose “language and style” demonstrated that it was from the times of the rishonim has attribution problems. To be sure, Assaf isn’t saying this responsum isn’t necessarily from the rishonim period, however, it surely isn’t from Rashba.[15]

Or, to take another example. Talya Fishman argues that “[halakhic literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries . . . climbed to new (and fantastic) heights of theoretical speculation, creating, in effect, a body of non applied law.” Talya Fishman, “

Forging Jewish Memory: BR and the Invention of Pre-emancipation Jewish Culture,” in

Jewish History and Jewish Memory, ed. Carlbach et al., Hanover and London: 1998, pp. 70-88. Based on this understanding of seventeenth and eighteenth century literature, as contrasted with literature from the period of Rosh, she turns to the BR and finds such speculative responsa. This, according to Fishman, implicitly demonstrates that BR is a product of the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Indeed, Fishman concludes “[i]n short, [BR], has an unusually high concentration of eyebrow-raising cases.”

Id. at 76.

But, if one subjects Fishman’s argument to even a minimal amount of scrutiny, her argument, as presented, is unconvincing. First, in support of Fishman’s “high concentration” of odd responsa, Fishman provides three examples. That is, Fishman points to three out of 392 responsa that contain “eyebrow-raising cases” and concludes this represents “an unusually high concentration.” I think that most would agree that less than 1% does not represents an unusually high concentration. Second, of the three examples Fishman does provide, one is from Kasa deHarshena, which everyone agrees is a product of the eighteenth century. Third, one of the examples, no. 100, it appears that Fishman misread the responsa. Fishman provides that responsa 100 is a “bizarre question about whether a one-armed man should don tefilin shel yad on his forehead alongside tefilin shel rosh.” Id. at 76. Indeed, responsa 100 is about a one-armed man and whether because he cannot fulfill the arm portion of tefilin if that absolves him of the head portion. Nowhere, however, not in BR or Kasa de-harshena, does it mention the possibility of putting the tefilin shel yad on one’s forehead. Thus, if we discount these two responsa, Fishman is left with a single responsum to prove her generalization about BR.[16]

Regarding the manuscript, that too is an unsolved mystery. We know that a manuscript that may have been the copy which R. Hirschel made is extant but the manuscript from di Molena is unknown. Additionally, although we know that the Leningrad/St. Petersberg library had Tzvi Hirsch’s copy with his annotations, the current location of that book is unknown. See Benjamin Richler’s post regarding the manuscript

here.

The BR’s most lasting effect may be in that this was to be the first of many newly discovered manuscripts to be accused of forgery because of the conclusions reached. Subsequent to the BR, responsa or works in other areas of Jewish literature were tarred with cry of forgery because of their conclusions. [See Yaakov Shmuel Spiegel, Chapters in the History of the Jewish Book, Writing and Transmission, Ramat-Gan, 2005, 244-75, (“until the publication of BR, there were no questions raised regarding the authenticity of a book”) Spiegel also demonstrates that we now know that in many instances that the charge of forgery was wholly without basis and today there is no question that some of the books that are alleged forgeries are legitimate.]

Other Works by Saul Berlin

One final point. While we discussed Saul’s work prior to BR, there was another book that he wrote, that was published posthumously. This work,

Ketav Yosher, defended Naftail Wessley and his changes to the Jewish educational system. Indeed,

Ketav Yosher, is a scathing attack on many traditional sacred cows. [17]

Ketav Yosher, like MY, was published without Saul’s name, but again, we have testimony that Saul was in fact the author. In light of the position

Ketav Yosher takes, it is no surprise that this book doesn’t help Saul’s standing among traditionalists.

Saul may have written additional works as well, however, like the BR itself, there is some controversy surrounding those additional works. R. Saul’s son, R. Areyeh Leib records an additional 11 works that Saul left behind after he died. The problem is these very same works – although all remaining in manuscript – have been attributed to someone else. But, before one jumps to conclusions, it should be pointed out that this story gets even more complicated. The book which attributes these works to another is itself problematic. Indeed, whether this list attributing the books to another even exists is a matter debate. And, while that sounds implausible, that, indeed is the case. Ben Yaakov, Otzar ha-Seforim (p. 599 entry 994) says there is a 1779 Frankfort Order edition of Sha’ar ha-Yihud/Hovot ha-Levovot that includes an introduction (and other material) that lists various manuscripts which the editor, according to Ben Ya’akov, was a grandson of Yitzhak Yosef Toemim, ascribes to his grandfather – and not Saul. Weiner, in his bibliography, Kohelet Moshe, (p. 478, no. 3922) says that Ben Ya’akov is wrong – not about the edition, Weiner agrees there was a 1779 Frankfort Oder edition, just Weiner says there is no introduction and Toemim wasn’t the editor (and other material is missing). Vinograd, Otzar Sefer ha-Ivri lists such a book – 1779 Frankfort Oder, Hovot ha-Levovot/Sha’ar ha-Yichud, but there is no such edition listed in any catalog that we have seen including JNUL, JTS, Harvard, British Library etc. It appears that Samat couldn’t locate a copy either as although he records the dispute between Weiner and Ben Yaakov, he doesn’t offer anything more. Thus, Saul’s other writings, for now, remains an enigma.

It is worthwhile to conclude with the words of R. Matisyahu Strashun regarding Saul and the BR:

“After all these analyses, even if we were able to prove that the entire BR from the begininning to end is the product of R. Saul, one cannot brush the work aside . . . as the work is full of Torah like a pomegranate, and the smell of besamim is apparent, it is a work full of insight and displays great breadth, the author delves into the intricacies of the Talmud and the Rishonim, the author is one of the greats of his generation.” Shmuel Yosef Finn, Kiryah Ne’amanah, notes of R. Strashun, p. 93.

The Internet

As hopefully should be apparent, most of the books discussed above or referenced below are available online. These include the

rare retraction that R. Saul published regarding his position on shaving on hol ha-ma’od,

Ketav Yosher, the

prospectus for BR, as well as the

BR itself. Indeed, not only is the BR online but both editions are online. And, the BR exemplifies why one should be aware of multiple internet sources. Hebrewbooks has a

copy of BR which they indicate is the first edition “Berlin, 1793,” however, in reality it is the later, 1881 Warsaw edition of the BR. As noted above, that edition, however, is lacking two responsa. This highlights an issue with Hebrewbooks, the bibliographical data is not necessarily correct. The JNUL, has the

first edition. Indeed, in the case of the JNUL, the bibliographical information is much more reliable than Hebrewbooks. Thus, one needs to use both the JNUL as well as Hebrewbooks if one wants to get a full picture of the BR. Or, another example. Both the

JNUL site as well as

Hebrewbooks has MY online; but, the

JNUL version was bound with two rare letters at the end and those appear online as well. Additionally, when it comes to Hebrewbooks, one must be aware that they have removed books that someone presumably finds objectionable so although MY and KY are there now, there is no guarantee it will be in the future. Similarly, although not online, and unlike the MY the JNUL has, Otzar haChomah has the

Ze’ev Yitrof with additional material bound in the back. Besides for all these rare seforim mentioned, many of the other seforim quoted in this post, as is apparent from the links, can now be found on the web in a matter of seconds instead of what just a few short years ago would have taken a nice long trip to an excellent library.

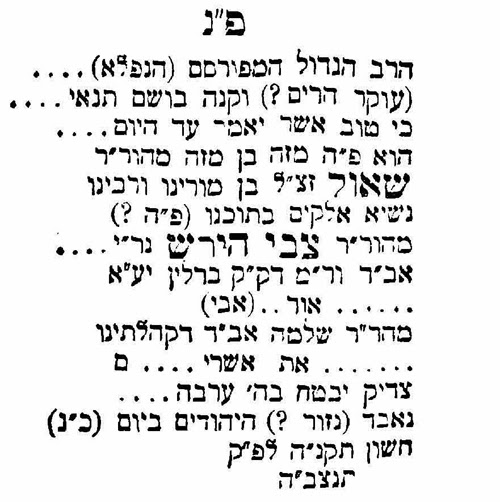

Saul’s Epithet, he was buried in the Alderney Road Cemetery in London, next to his brother, Hirschel, Chief Rabbi

Notes

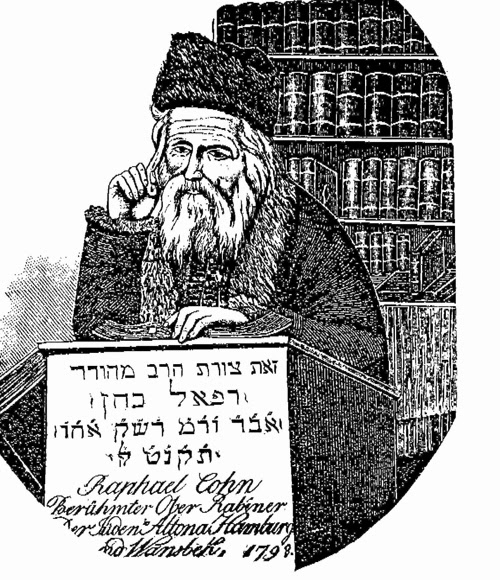

[1] For more on R. Raphael Cohen see the amazingly comprehensive and insightful bibliography by the bibliophile R. Eliezer Katzman, “A Book’s Luck,”

Yeshurun 1 (1996), p. 469-471 n.2. See also R. Moshe Shaprio,

R Moshe Shmuel ve-Doro pp.103-110 especially on the BR see 108-09. C. Dembinzer,

Klielas Yoffee, 1:134b, 2:78b writes that the work on TY caused R. Saul to lose his position as Chief-Rabbi of Frankfort and his wife divorced him because of it. See also, S. Agnon,

Sefer Sofer Vesipur, p.337. On R. Raphael Cohen and his connection with the Gra and Chasidus see D. Kamenetsky,

Yeshurun, 21, p. 840-56. As an aside this article generated much controversy for example see the recent issue of

Heichal Habesht, 29, p.202-216 and

here.

[2] Regarding the correct pronunciation of this title see Moshe Pelli, “The Religious Reforms of ‘Traditionalist’ Rabbi Saul Berlin,” HUCA (1971) p. 11. See also R. Shmuel Ashkenzi’s notes in the BR, Jerusalem, 1983 ed., introduction, n.p., “Notes of R. Shmuel Ashkenzi on Kuntres Yefe le-Besamim, note 6.

Additionally, MY was not Saul’s first literary production, nor was it his first that was critical of another’s book. Instead, while he was in Italy in 1784, he authored a

kunteres of criticisms of R. Hayyim Yosef David Azulai’s

Birkei Yosef. See R. R. Margolis,

Arshet pp. 411-417; Moshe Samat, “Saul Berlin and his Works,”

Kiryat Sefer 43 (1968) 429-441, esp. pp. 429-30, 438 n.62.

On Chida’s opinion of the BR see for example

Shem Hagedolim:

עתה מקרוב נדפס ספר זה בברלין… ועוד יש הגהות כסא דהרסנא. ואשמע אחרי קול רעש כי יש בספר זה קצת דברים זרים ואמרו שהמעתיק הראשון בארץ תורגמה מכ”י הרב יצחק די מולינא ז”ל יש לחוש שהוסיף וגרע. ולכן הקורא בסי’ זה לא יסמוך עליו דאפשר דתלי בוקי סריקי בגדולים עד אשר יחקור ויברר הדברים ודברי אמת ניכירים ודי בזה… (שם הגדולים, ערך בשמים ראש, וראה שם, ערך מר רב אברהם גאון)

See also the important comments of R.Yakov Chaim Sofer, Menuchas Sholom, 8, pp. 227-230 about the Chida.

[3] Eliezer Landshut,

Toldot Anshei Shem u-Puolotum be-Adat Berlin, Berlin: 1884, 89-90 for the text of the ban as well as its history. Additionally, for the proclamation read in the main synagogue of Altona see

id. at 90-1. This proclomation has been described as “one of the harshest condemnations” of the time. See Shmuel Feiner,

The Jewish Enlightenment in the Eighteenth-Century, Jerusalem: 2002, p. 310.

[4] Id. at 91. Samat, however, notes that neither Saul nor his father ever admitted Saul’s authorship of MY. Samat, “Saul Berlin and his Works,” p. 432, 4.

[5] According to A. Berliner, the author of this pamphlet is R. Eliezer Heilbot. See Samat,

id. Saul and MY were not the only ones attacked. The publisher of MY,

Hinukh Ne’arim, was also attacked and, not only MY but all the books they published were prohibited by some. The publishers, however, defended their decision to publish MY. They argued that the whole point of MY was to ascertain if R. Raphael Cohen’s book was riddled with errors or, the author of MY was mistaken. The publishers pointed to the above mentioned introduction to MY wherein the MY’s author explains that he has sent copies of the book to leading rabbis to determine the question regarding R. Cohen’s book. Thus, MY is either right or wrong, but there can be nothing wrong with merely publishing it.

See id. at 92-3.

Additionally, it should be noted that according to some, Saul authored a second attack on R. Raphael. R. Raphael published

Marpeh Lashon, Altona, 1790, and was soon after attacked in the journal

Ha-Meassef by someone writing under the pen-name EM”T. Many posit that this is none other than Saul. Katzman,

Yeshurun 1, 471 n.3, disagrees and points to internal evidence that it is unlikly that Saul is the author of this critique.

According to Feiner, these attacks were not one-sided. Feiner argues that R. Cohen criticizes Saul, albeit in a veiled manner, in Marpeh Lashon. See Feiner, Jewish Enlightenment, op. cit., 314-15.

[6] Landshuth, id., suggests that Moshe is a non-existent figure like MY’s putative author Ovadiah. See also, Samet, “Saul Berlin and his Works,” 432 n.4 who similarly questions the existence of Moshe. Carmilly-Weinberg makes the incredible statement that his Moshe is none other than Moses Mendelssohn. Carmilly-Weinberg, Sefer ve-Seiyif, New York, 1967, p. 215, (Carmilly-Weinberg’s discussion about both MY and BR are riddled with errors). As Pelli notes this is impossible as the letter is signed 1789, the same year MY was printed, and Mendelssohn died three years prior. Pelli resurrects Moshe and links him with a known person from Amsterdam, Saul brother-in-law. See Pelli, HUCA (1971) p. 13 n.75. Ultimately, however, Pelli rejects this and demonstrates that Moshe is indeed a pseudonym but a well-selected one. See id.

[7] See Landshuth, 93-9; Pelli, 13-15. See also R. Alexander Sender Margolioth,

Shu”t ha-RA”M, Lemberg, 1897, no. 9.

[8] See Feiner,

The Jewish Enlightenment, op. cit., 312-13. This newspaper is online

here, and Feiner provides the relevant issues which are 1789 pp. 484-88, 520-24, 574-81, 680-82, 768-74, 791-802, 867-92, 932-72.

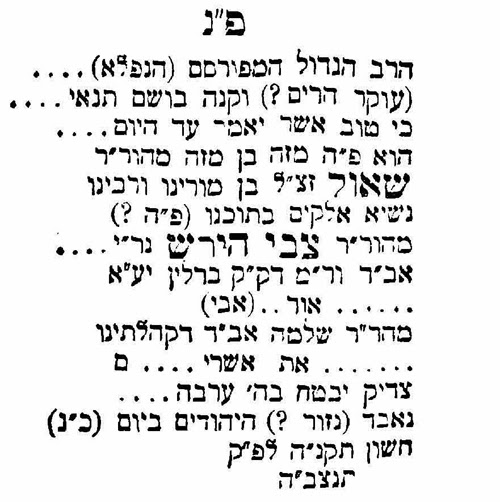

One of which includes this portrait of R. Cohen.

Which is a very different portrait, both in time and look, to the one appearing in E. Duckesz,

Ivoh le-Moshav, Cracow, 1903.

[9] For the deeper meaning of the title Kasa de-Harshena, see Moshe Pelli, The Age of Haskalah, University Press of America, 2006, 183 n.51.

[10] See Samat, who discusses the exact progression of the ban.

[11] See Yechezkel Shrage Lichtenstein,

Suicide: Halakhic, Historical, and Theological Aspects, Tel-Aviv, 2008, pp. 438-44. See also,

Yeshurun 13:570-587 especially pp.578-581; Marc B. Shapiro, “Suicide and the World-To-Come,” AJS Review, 18/2 (1993), 245-63.

On the issue of suicide there are others who similarly reach the same holding as the BR see Strashun in his

מתת-יה pp. 72a-72b (this source is not quoted by Samet or Amar).

[12] Biographical information on R. Yosef Lazer is scant. For information on his father and grandfather, see Meir Wunder, Me’orei Galicia, Israel, 1986, vol. III, pp. 456, 462-3. See also T.I. Abramsky, “‘Besamim Rosh’ in the Hassidic Milieu,” Taggim, (3-4), 56-58.

[13] Samat only notes the removal of one responsum, he fails to note that exclusion of the second. He does, however, note the misplaced responsum. Additionally, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot ha-Hadash, fails to record that any are missing or that one responsum was moved to the end.

[14] See Pelli,

Age of Haskalah, pp. 185-89, comparing a few responsa with 18th century

haskalah literature.

[15] Assaf was not the first to use this responsa and note its historical anacronisms. Leopold Zunz, also highlights the issues with this responsum (as well as others). Leopold Zunz,

Die Ritus des Synagogalen Gottesdienstes, Geschichtlich Entwickelt, Berlin: 1859, 226-28. Zunz’s critique is quoted, almost in its entirety by Schrijver, but Schrijver appears to be unaware of Assaf’s additional criticisms of the responsum (and others).

Assaf provides one other example where he shows through internal data that there is a misattribution. Assaf concludes that he has other examples of historical anacronisms in BR but doesn’t provide them here or, to our knowledge, anywhere else.

Additional Bibliography:

M. Samet has two articles on the topic, R. Saul Berlin and his Writings, Kiryat Sefer, 43 (1969) 429-41; “Besamim Rosh” of Saul Berlin, Kiryat Sefer 48 (1973) 509-23, neither of which are included in the recent book of Samet’s articles.

To add to Samet’s and Amar’s very comprehensive lists of Achronim who quote BR: (I am sure searches on the various search engines will show even more): Malbim in

Artzos Hachaim, 9:41 (in Hameir Learetz);

Shut Zecher Yosef,1:32b;

Keter Kehunah p. 30;

Matzav Hayashar 1:2a;

Pischei Olam 2:218,228;

Birchat Yitchcak (Eiskson), pp. 6,14,24;

Maznei Tzedek, p.26,45,254; R.Yakov Shor,

Birchat Yakov, pp.212

Sefer Segulos Yisroel pp.116b; R. Rabinowitz

, Afekei Yam 2:14; R. Leiter,

Zion Lenefesh Chayah# 43;

Shut Sefas Hayam, OC siman 14;

R Meir Soleiveitck, H

ameir Laretz 45a, 45b, 54b, 55a;

Emrei Chaim p.26; R. Sholom Zalman Auerbach,

Meorei Eish p. 108 b

In general on BR see: R.Yakov Shor,Eytaim Lebinah (on Sefer Haeytim) p. 256; Pardes Yosef, Vayikrah 220b Pardes Yosef, Shelach p. 517; R.Yakov Chaim Sofer, Menuchas Sholom, 8, pp. 222- 230; Shar Reven p. 54; A. Freimann, HaRosh ; Y. Rafel, Rishonim Veachronim, pp. 123-130; B. Lau, MeMaran Ad Maran, pp.133; S. Agnon, Sefer Sofer Vesipur, pp.337-339.

R. Pinhas Eliyahu Horowitz writes:

ולפעמים תולים דבריהם באילן גדול וכותבים מה שרוצים בשם איזה קדמון אשר לא עלה על לבו… כספר בשמים ראש שחיבר בעל כסא דהרנסא לא הרא”ש וזקני ישראל תופסי התורה יעלו על ראשם… (ספר הברית, עמ’ 232).

The Steipler was of the opinion in regard to the BR that:

שבאמת ניכר מהרבה תשובות שהם מהרא”ש ז”ל רק כנראה שיש שם הרבה תשובות מזויפות שהמעתיק הכניס מעצמו כי ישנם שם דברים מאד מזורים ואיומים (ארחות רבנו, א, עמ’ רפה)

R Zevin writes in Sofrim Veseforim (Chabad) p.354 :

אלא שבתשובות בשמים ראש המיחוס להרא”ש ושכידוע נמנו וגמרו שמזוייף הוא

R. Yakov Kamenetsky said: “Do you think Just we (he meant people of his own caliber) were fooled? Even R. Akiva Eiger was fooled.” (Making of a Godol, pp.183-184)

About Rav Kook and the BR see: http://www.biu.ac.il/JS/JSIJ/5-2006/Gutel.pdf

R. Avigdor Nebensal writes:

כשמביאם את הבשמים ראש ראוי להזכיר שיש מסתייגים חריפות מהספר הזה (השתנות הטבעים, עמ’ 16).

R Zalman Nechemiah Goldberg writes:

אכן בעיקר הענין אם להביא דברי בשמים ראש בודאי צדק הג”א נבנצל שליט”א שיש להביאו בהסתייגות, ובפרט בענינים אלו שהוחזק למזייף ולמביא עקומות וכוזבות (השתנות הטבעים, עמ’ רסד).