Summary of Jordan Penkower on reading Zekher or Zeikher Amalek

Summary of Jordan Penkower on reading Zekher or Zeikher Amalek

This post originally appeared here. It is a summary of Prof. Jordan Penkower’s Minhag u-Mesorah: ‘Z-kh-r Amalek’ be-hamesh o be-shesh nekudot by his student Yosef Peretz. It appears here with permission, with some additions by the Seforim Blog editor.

It is common practice in most Ashkenazi congregations to read the words z-kh-r Amalek, in Deut. 25:19, twice: once with a tzere under the zayin (zeikher) and once with a segol (zekher). Sephardic congregations, however, who do not distinguish between the pronunciation of these two vowels, read it only once, and they point it with a tzere. What is the origin of this practice, when did it begin, and is this double reading necessary to fulfill the command of reading these verses of Parshat Zakhor, the special reading on the Sabbath before Purim? These questions are discussed in several articles by R. Mordechai Breuer and Dr. J. Penkower,[1] two of the most eminent among contemporary scholars of the masorah and Biblical text. In their opinion, zeikher with a tzere is beyond a shadow of doubt the original and correct pointing of the text; and that is how the verse should be read in Parshat Zakhor. It must be stressed that the custom itself of a double reading is quite surprising and completely unique in Torah reading, for it was customary to decide in favor of one reading or another whenever there was a conflict between variant readings, pointing of vowels, or assignment of cantillation marks (as in cases of kri and ktiv, where a word is written one way but read another). R. David Kimhi, in his Sefer ha-Shorashim (in the manuscript versions), was the first to note the discrepancies regarding the pointing of these vowels in Sephardic biblical manuscripts. Under the root z-kh-r he says: “‘blot out the memory (zekher) of Amalek’ (Deut. 25:19), with six dots (i.e., segol twice), but ‘praise [in remembrance of (le-zekher)] His holy name’ (Ps. 30:5), with five dots (i.e., a tzere and a segol), and this occurs nowhere else; thus it appears in some books [i.e. manuscripts of the bible containing the Masorah]. But in others, z-kh-r is always pointed with five dots.” In other words, Radak noted that in some books he found z-kh-r pointed with segol and in others, with tzere. In printed editions of Sefer ha-Shorashim, however, beginning with the Venice edition and carrying through the 19th century, Radak’s remark concludes with the words “and this occurs nowhere else.” In other words, he found zekher in Parshat Zakhor always pointed with double segol.[2]

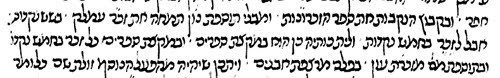

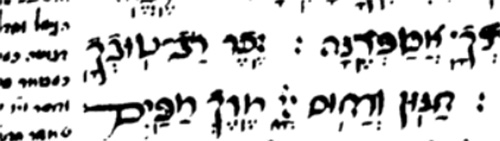

Here is a typical example in a manuscript (from 1481):

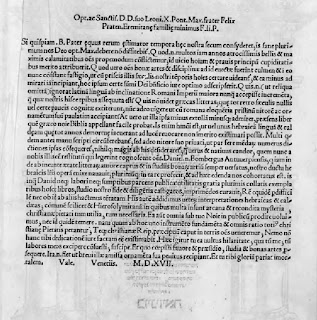

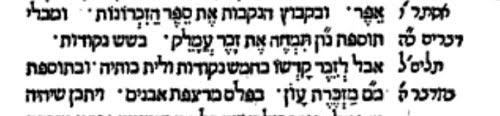

And here is the Venice edition: Here is the manuscript text restored in Biesenthal and Lebrecht’s Berlin 1847 edition:

Here is the manuscript text restored in Biesenthal and Lebrecht’s Berlin 1847 edition:

Various prayer books and Pentateuchs published in the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries were redacted according to Radak’s remark as it appears in these printed editions; for example, the siddur of R. Shabtai Sofer (in the word zekher in the Ashrei prayer and in the prayers on the eve of the New Year), and Meor Einayim, the Pentateuch published by R. Wolf Heidenheim.*

The Basel 1579 Seder Tefillot Mi-kol Ha-shanah (Ashkenaz):

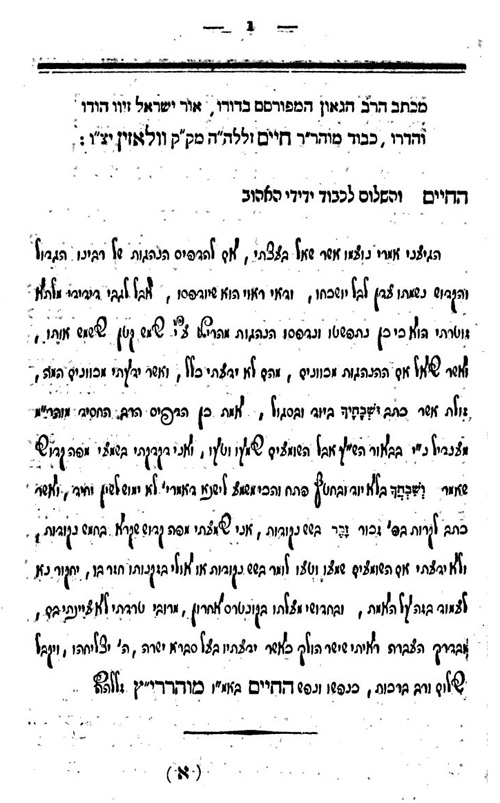

The manuscript of R. Shabtai’s siddur: In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”

In 1832, about fifteen years after publication of Heidenheim’s edition, a book by R. Issachar Baer appeared, entitled Ma`aseh Rav, containing a description of the practices of the Vilna Gaon. The author mentions that the Gaon’s disciples disagreed over the way their teacher used to read the word zekher in Parshat Zakhor. The author attested as follows: “When he would read Parshat Zakhor, he would say zekher, with a segol under the letter zayin. R. Hayyim of Volozhin, however, whose endorsement is on the book, wrote there, `As for his writing that in Parshat Zakhor one should read [z-kh-r] with six dots, I heard from the saintly person [i.e., the Gaon of Vilna] that he read with five dots (=zeikher).’ I do not know whether those hearing him were mistaken, and thought they heard segol twice, or whether he changed his practice in his later years.”

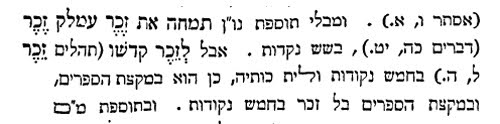

Here is the text, with the footnote referring to R. Hayyim of Volozhin’s testimony:

Here is R. Hayyim’s testimony in his approbation at the beginning of this work:

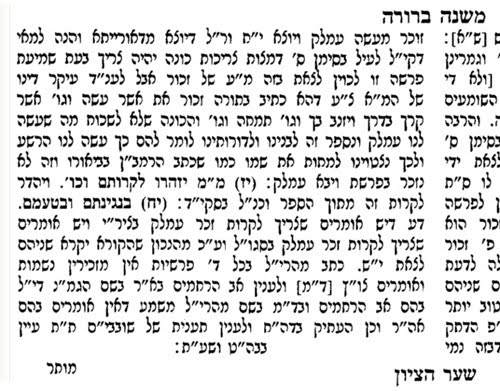

Approximately eighty years later, R. Israel Meir Ha-Cohen, otherwise known as the Hafetz Hayyim, came out with his Mishnah Berurah on the Shulhan Arukh. Since the special reading of Parshat Zakhor is a command from the Torah, and there was some doubt as to the correct reading, he ruled that the words z-kh-r Amalek should be read twice. In his own words, “Some people say it should be read as zeekher Amalek (Deut. 25:19) with a tzere, and others say that it should be read as zekher Amalek with a segol; therefore the correct practice is to read both ways, to satisfy them both” (Mishnah Berurah 685.18). Later, a variety of customs emerged in this regard. Some readers only repeat the two words, z-kh-r Amalek, while others repeat the entire phrase, timhe et z-kh-r Amalek, and still others repeat the entire verse.[3]

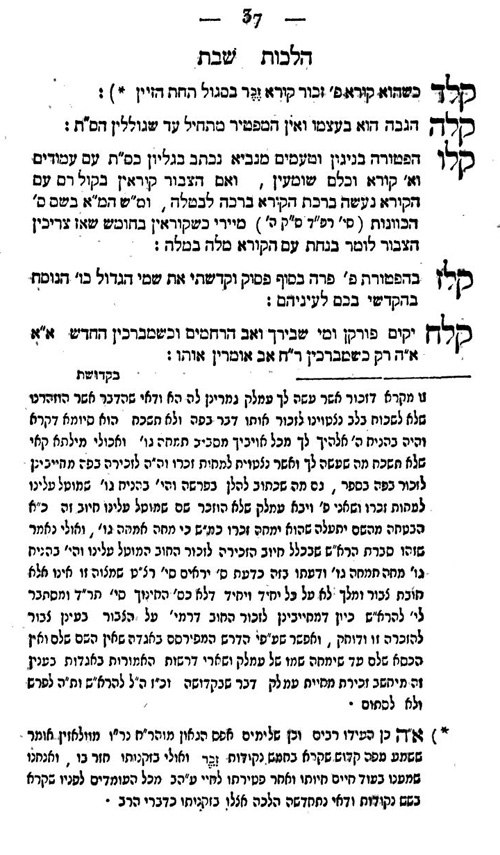

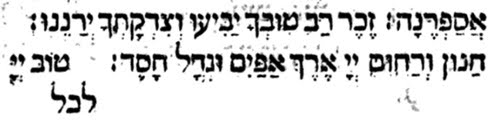

Here is the Mishnah Berurah:

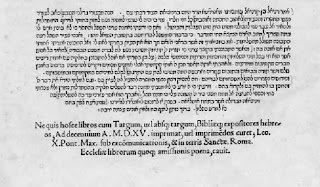

As mentioned above, Rabbi Breuer and Dr. Penkower note that the correct pointing of z-kh-r is with a tzere and the custom of double reading is unfounded. This follows from the arguments they cite from the masorah, from the ancient and highly precise Tiberian manuscripts and teachings of the Masoretes. R. Jedidiah Solomon Norzi, a seventeenth century masoretic scholar, held to be the final arbiter on the text of the Bible,[4] wrote a work entitled Minhat Shai, in which he remarks on inaccuracies that entered all the books of the Bible in the 1547-1548 Venice edition of Mikraot Gedolot and other editions published around then.[5] He says nothing about zekher ,which is pointed with a tzere followed by segol, from which it follows that he agreed with this pointing and had no doubts about it being correct.[6]

Minhat Shai from the first edition (Mantua 1742-4):

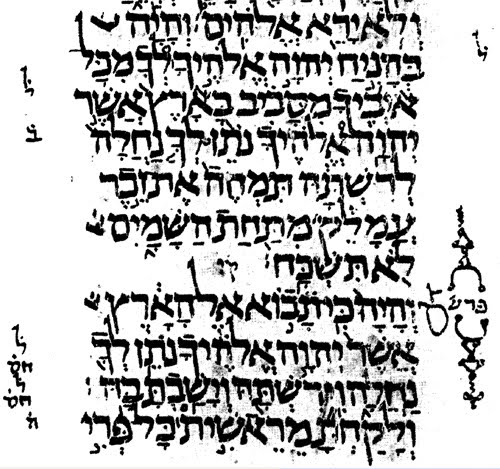

The most conclusive proof is found in ancient manuscripts, dating to the time of the masorah, and held to be very precise in their pointing and cantillation marks: the Leningrad manuscript (known as B19),[7] the Sassoon 1053 manuscript and others. All point z-kh-r with a tzere under the zayin.[8]

Leningrad manuscript:

Today we have in our hands a famous ancient manuscript, the Keter Aram-Tzova,[9] the most ancient and best authorized text of the entire Bible. The pointing and masoretic annotation of this manuscript were done in Israel over one thousand years ago by Aharon Ben-Asher, considered the greatest Masorete of all generations. Due to Ben-Asher’s precision and reputation, Maimonides chose to base his Hilkhot Sefer Torah on Ben-Asher’s work.[10] In the 15th century, at the latest, the Keter manuscript was transferred to Aleppo, Syria, where it was stored in the Sephardic synagogue until the riots against the Jews of Aleppo (Aram Tzova) that broke out in 1948, during which the manuscript was damaged, most the entire Pentateuch being lost, including Parshat Zakhor. Because the Keter manuscript was so special, the Jews of Aleppo did not allow others to photograph the manuscript or to examine it. Whoever wished to clarify a question of variants in the text had to write down the query and the person in charge would relay the version found in the Keter. The most famous of those addressing queries was R. Jacob Saphir, who submitted over five hundred questions, seeking to find out what variant appeared in the Keter. Fortunately, one of his questions pertained to the pointing of z-kh-r in Parshat Zakhor. The question and response were as follows: “(Deuteronomy) 25:19 z-kh-r h”n [question]. Yes [response].” In other words, is the word z-kh-r pointed in the Keter with five dots [h”n = hamesh nekudot, five dots,i.e., tzere followed by segol]? The answer provided by the keeper of the manuscript, R. Menashe Sitton, was” yes”.[11]

The entry in the published version of this manuscript (Rafael Zer Meorot Natan Le-rabbi Ya’akov Saphir, Leshonenu 50:3,4 Nisan-Tamuz 5746):

Dr. Penkower examined the pointing of z-kh-r in dozens of medieval manuscripts and found that in those manuscripts reputed to be more precise (some of the Sephardic ones) it was pointed with a tzere, and in those reputed to be less precise (some of the Sephardic ones and most of the Ashkenazi ones) it was pointed with a segol. These findings led him to note, “If we were to start taking into account the pointing in manuscripts far removed from the precise Tiberian ones, and were to begin reading doubly all instances of variation between them and the precise manuscripts, the Torah reading each week would last an inordinately long time.”[12] All editions of the Bible today point z-kh-r with tzere followed by segol, leaving no vestige of the double segol variant. One cannot but agree with R. Breuer and Dr. Penkower that there is no need for Ashkenazim to read zekher, for zeikher will suffice. To sum up: * R. David Kimhi mentions two methods of pointing which he observed in Sephardic manuscripts: zekher and zeikher. * The disciples of the Vilna Gaon disagreed about how their Rabbi used to read this word in Parshat Zakhor, whether with a tzere or a segol. * Because of uncertainty as to which was correct, the Mishnah Berurah ruled that z-kh-r Amalek should be read twice, once with tzere and once with segol. * The findings presented by R. Breuer and Dr. Penkower prove conclusively that the correct and original pointing of this word is zeikher (with a tzere). Therefore, in their opinion, one should return to the ancient practice, and all Jewish communities ought to read the word only once, as zeikher. [1] M. Breuer, “Mikraot she-yesh lahem hekhre`a,” Megadim 10 (1990), pp. 97-112; J. S. Penkower, “Minhag u-Mesorah: ‘Z-kh-r Amalek’ be-hamesh o be-shes nekudot” (with appendices, in R. Kasher, M. Tzippor and Y. Tzefati, eds., Iyyunei Mikra u-Farshanut, 4, Bar Ilan University Press, Ramat Gan 1997, pp. 71-127. [2] Penkower (loc. cit., p. 80 ff.) discusses at length the differences between manuscript and printed versions of Sefer ha-Shorashim. [3] On other practices, see Penkower, loc. sit., p. 71, n. 1. [4] Y. Yevin, Mavo la-Masorah ha-Tverianit, Jerusalem 1976, p. 101 ff. [5] J. S. Penkower, Ya`akov Ben Hayyim u-Tzmihat Mahadurat ha-Mikraot ha-Gedolot I-II (Dissertation), Jerusalem 1982. [6] R. Jedidiah Solomon Norzi was preceded by another important masoretic scholar, R. Menahem de Lonzano, author of Or Torah. In his book, he remarks on the same editions of Mikraot Gedolot on the system of vowel pointing and cantillation marks, but also says nothing about z-kh-r being pointed with a tzere followed by segol. [7] The printed Bible published for the IDF, prepared by Prof. A. Dothan, is based on this manuscript.[8]For further detail, see R. Breuer’s article (cited in n. 1), p. 110, and Penkower’s article (cited in n. 2), p. 101. [9] This manuscript is also known as the Aleppo Keter, or simply the Keter for short. [10] Several printed Bibles based on the Keter are available today. The most important of these is undoubtedly the Mikraot Gedolot- ha-Keter, redacted and edited by Prof. Menahem Cohen, Bar Ilan University Press, Ramat Gan 1992 and following years. Thus far five volumes have been published, covering the following six books of the Bible: Joshua-Judges (including a general introduction to the edition), Samuel I and II, Kings I and II, Isaiah, and Genesis vol. 1. [11] The manuscript containing these questions and responsa is known as Meorot Natan. See here.

[12] At the Project on Bible and Masorah at Bar- Ilan University, headed by Prof. M. Cohen, dozens of medieval manuscripts of the Bible were examined, and the findings of these studies reinforce Penkower’s conclusions regarding variant pointings in the manuscripts.

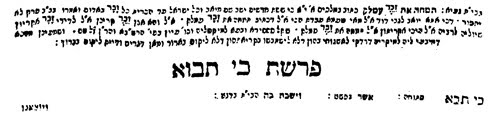

* Seforim Blog editor note: the issue is discussed in the En Hakore commentary included by Heidenheim in Humash Meor Einayim, only in the parashah of Amalek in Exodus 17, not in Deuteronomy. En Hakore is a masoretic commentary by R. Yekutiel (or Zalman) Ha-nakdan who lived in Prague in the 13th century. Here is how it appears in Heidenheim’s Humash Meor Einayim. However, it appears to be a misstatement to say that Heidenheim was among those whose work was “redacted according to Radak’s remark,” for while there is no example of Zekher from Psalms to compare with in his Humash Meor Einayim, Zekher is also pointed with tzere , rather than segol, in the Ashrei prayer included in Humash Moda Le-vina. This would seem to indicate that he did not follow the Radak. He merely published En Hakore, which dealt with the issue raised by Radak.