Akedah, Art, and Illustrations in Hebrew Books

At most in Haggadot or on title pages, at times, there are minor illustrations. But, there is a notable exception.

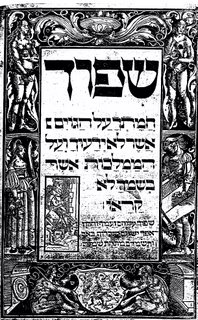

At most in Haggadot or on title pages, at times, there are minor illustrations. But, there is a notable exception.In his later work Et Kets, also published in Amsterdam in 1710 he includes another depiction of the Akedah. This work is devoted to figuring out when the Messiah will come, (he thinks in 1740), a much more upbeat topic than his prior work. As you can see both illustrations, it bears discussing them in some detail.

The illustrations are most likely done by two different artists. This is so, as there are slight distinctions between the two. For instance, in the earlier one, Abraham has a full beard, while in the later one he only has a mustache. The ram in the first has straight horns, while in the second has circular ones.  These distinctions, however, are not as meaningful as others.

These distinctions, however, are not as meaningful as others.

The overall depictions are of two different time periods. In the first, the illustrations depicts Abraham just as he was about to slaughter Isaac and the angel calling out to stop him. But, in the second the illustration is of Abraham going after the ram and not Isaac. The signifcance of this is tied to the actual books. In Pachad Yitzhak the book discusses a terrific threat to the Jews and their salvation. Thus, the illustration is of the same – the terrific threat to Isaac and the salvation. The second work, Et Kets, is a much more positive book. This work has none of the fear of the prior instead, is fully devoted to Messiah and thus the illustration is only of the ram and its sacrifice.

Further, there are different Hebrew words which appear on both the illustrations. On the first the word ערכה (prepared or set up) appears across Abraham’s chest. This word expresses Abraham’s readiness to sacrifice Isaac. It would seem, similarly, the Jews of Padua were willing to sacrifice themselves for God. But the word ערכה only means to prepare and not to actually sacrifice. Thus, Isaac was only prepared but not sacrificed and so too the Jews of Padua were placed in danger but ultimately redeemed.

In Et Kets, the words ירא יראה appear. These words are a reference to what Abraham called the place where the Akedah took place. Importantly, Abraham uttered these words after the entire episode. These were words of jubilation on both him passing his test and Isaac’s redemption. Again, these words fit well with the content of Et Kets.

These allusions are unsurprising knowing the style of R. Dr. Cantarini. His books are written rather cryptically, with many many allusions to Biblical and other themes throughout.

Now, a word or two about the author. R. Dr. Isaac Cantarini lived in Padua. He came from a family of cantors or hazzanim. Thus, his name was בן חזן (ben hazzan – son of a hazzan) or in Italian Cantarini which has the same meaning. He received his medical degree from the University of Padua on the 11th of February 1664. He was a prominent Rabbi and the head of the Yeshiva in Padua. Among his students was R. Moshe Hayyim Luzzato (Ramchal). The Ramchal wrote a dirge on R. Dr. Cantarini’s death. R. Dr. Cantarini was a very popular speaker. One Shabbat, there were so many non-Jews in attendance, the Jews were forced to sit in the woman’s section. He authored repsonsa and appears in some of the contemporary responsas of his contemporaries. One work he appears in is R. Isaac Lamporti’s encyclopedia Pachad Yitzhak. Sharing the same first name and titling their books the same caused at least the Jewish Agency to conflate the two and erroneously claim about R. Dr. Cantarini that he “Published Pahad Yizhak (Fear of Isaac), a rabbinical encyclopedia which also described the attacks on the Padua community the year before.”

In his medical practice he was highly respected by both Jews and non-Jews. He left in manuscript some of his medical writings.

Note 1. At the end of his life the name Rafael was added, see Shmuel David Luzzato, Otzar Nechmad III p. 147.

Sources: Mordecai Ghirondi, Toldot Gedoli Yisrael, p. 143 no. 154; Joseph Gutmann, The Sacrifice of Isaac in Medieval Jewish Art, in Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 8 no. 16 (1987), pp. 67-89; Simon Ginzburg, The Life and Works of Moses Hayyim Luzzatto, index under Cantarini; S.D. Luzzato, Otzar Nechmad, III pp. 128-149; also the Jewish Encyclopedia has an entry (better than EJ) here.