Haggadah, First Hebrew Map, and Forgery

One of the most beautifully done haggadot is that of the Amsterdam, 1695. This haggadah for the first time used copperplate instead of woodcuts to produce the illustrations. Consequently, the illustrations are sharper and more intricate. The illustrator, Avrohom bar Ya’akov mimispchto shel Avrohom avenu, as is apparent from his name, was a convert. Before converting he was a preacher.

One of the most beautifully done haggadot is that of the Amsterdam, 1695. This haggadah for the first time used copperplate instead of woodcuts to produce the illustrations. Consequently, the illustrations are sharper and more intricate. The illustrator, Avrohom bar Ya’akov mimispchto shel Avrohom avenu, as is apparent from his name, was a convert. Before converting he was a preacher.

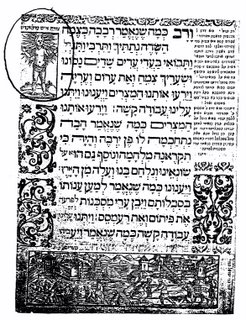

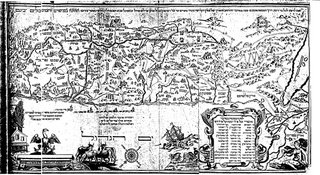

His edition of the haggadah was special not only for the copperplate and the illustrations, but for a specific illustration, one of the earliest Hebrew maps of Israel (the map on top, you can click to see a zoomable view). This haggadah included a fold out map (it was rather large) of the travels of the Jews through the desert and into Israel. Many (Yerushalmi and Yaari) incorrectly assert this was actually the first Hebrew map, however, as we will see in a moment that is wrong. But this map and the haggadah was rather popular and was reprinted four times in a little over one hundred years. [It was reprinted this year, however, the reprint is terrible. It seems they photocopied it and then had a three-year-old add color. The map is included in this reprint, not a fold out page, but as the end papers of the binding.]

The map itself has north on the right and east on the right as was common for maps of that time a compass is supplied in the bottom middle of the map. The legend on the top reads “This will allow every person to see the route of the forty year journey . . . ” And in keeping with previous Jewish books there is a nude in the lower right hand corner perhaps representing an Egyptian(?).

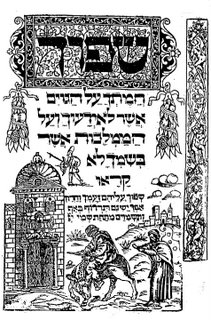

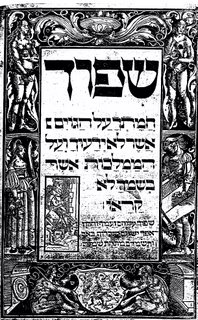

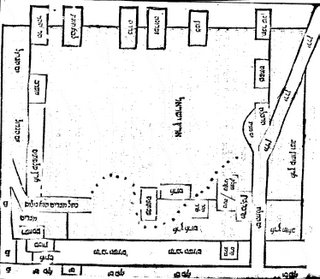

This was not the first Hebrew map of Israel. Instead, that milestone goes to a book with its own interesting history. The Biurim on Rashi was published in 1593 in Venice and attributed to R. Nathan Shapiro. This work includes two illustrations. The first is of the menorah (reprinted many times to this day) and the second is a map of Israel. This is the first Hebrew map. However, although on the title page this book is supposedly written by R. Shapiro, this was not the case. Instead, R. Shapiro’s son published his fathers comments on Rashi in 1697 in a work titled Imrei Shefer. In the introduction he explains why there are two books from his father both on the same topic.

ואתם קדושי עליון אל תתמהו על החפץ שזה שתנים ימים יצא בדפוס איזה ביאורים הנקראים על שם הגאון אדוני אבי ז”ל, כי המציאוהו אנשים, אנשי בלי עול מלכות שמים, חיבור אשר מצאו, ומי יודע המחבר אם נער כתבו ורצו לתלותו באילן גדול אדני אבי ז”ל, חלילה לפה קדוש להוציא מפיו דברים אשר אין בהם ממש, כי הכל תוהו ובוהו ומזויף מתוכו, כלו עלו קמשונים כסו פניו חרולים. וכאשר הגיעו הספרים ההם בגלילות אלו הכרוז בהסכמת כל רבני ורשאי המדינות שלא ומכרו ויהיו בבל יראה ובבבל ימצא בכל ארצות אלו. ואשר קנו מהם יחזר להם המעות ולא ימצא בביתך עולה

[“Do not wonder why I am publishing what was published just two years ago, the Biurim, in my father’s name. As wicked people, people who found a book, a book which may have been written by a child. However, they wanted to use my father’s good name to publish their work. But, my father would never say such stupidities which appear in that book, their book is worthless and a forgery. When this was discovered all the Rabbis agreed that this book [Biurim] should be under a ban, no one should be allowed to keep it. Whomever purchased it should have their money returned, they should not allow a stumbling block into their home.”]

So this book was actually a forgery and not really from R. Shapiro however, it still did provide the first map, albeit a crude one. In the Imrei Shefer there is no map.

His son was not the only one to question the authenticity of the Biurim. R. Yissachar Bear Ellenburg in his Be’er Sheva and in his Tzedah L’Derekh states unequivocally that R. Shapiro did not write the Biurim.

Sources: A. Yaari Maps of Israel in the Haggadah, Machanyim, 55 (1971) 152-159; (for more on converts in printing see Yaari, Mehker Sefer, 245-55); Introduction Imrei Sefer, Lublin 1697 (on differences in the printings of the Imrei Shefer see Yudolov, Areshet, 6 (1981) 102 no. 7); Biurim, Venice 1693; R. E. Katzman, “Rabbi Nathan Nata Shapiro – Ha-Megaleh Amukot” in Yeshurun 13 (Elul 2002) 677-700; Introduction [R. E. Katzman]Seder Birkat HaMazon im pirush shel R. Noson Shapiro, 2000 Renaissance Hebraica, 1-10; Yeushalmi, Haggadah and History, plate 69.