A Few Comments Regarding The First Woodcut Border Accompanying The Prague 1526 Haggadah

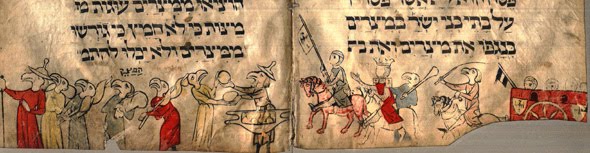

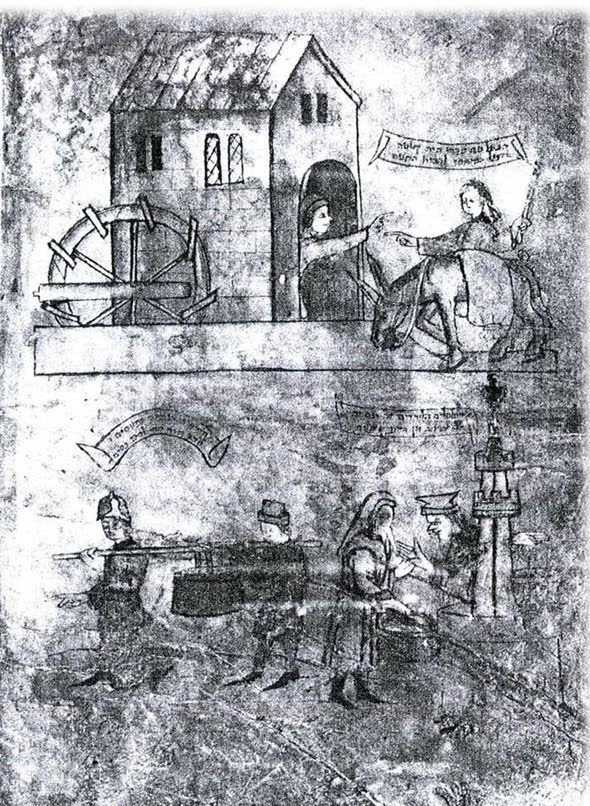

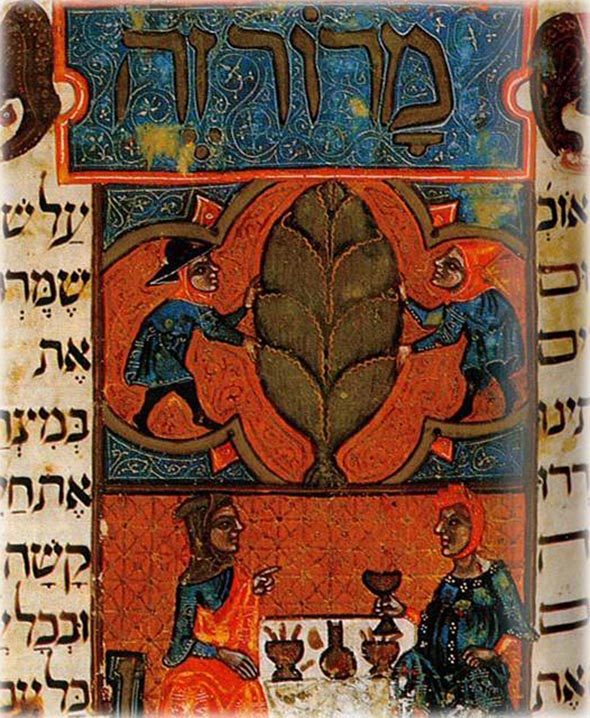

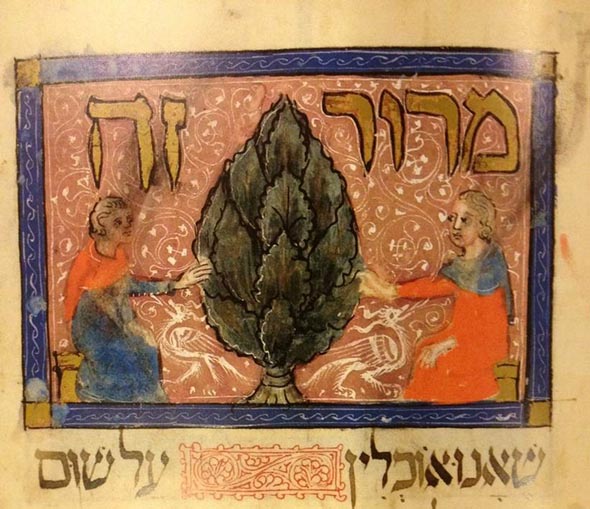

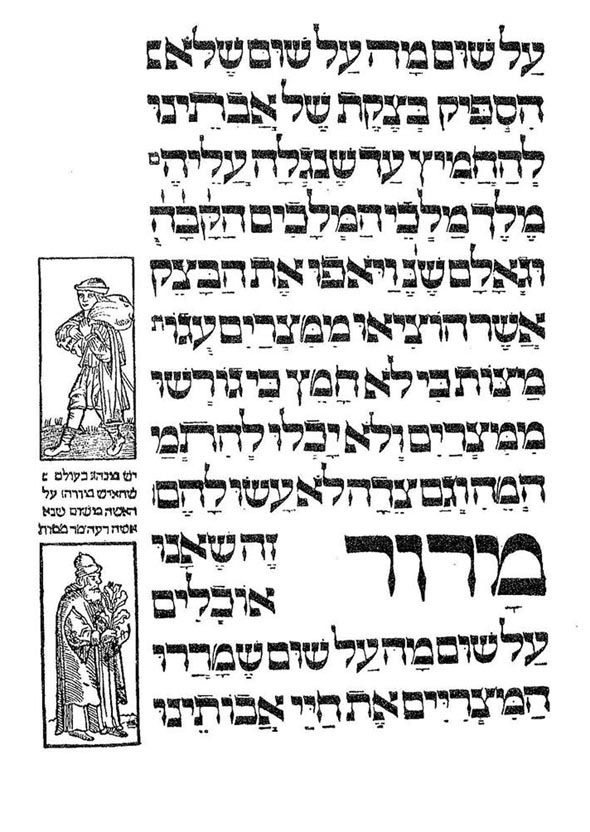

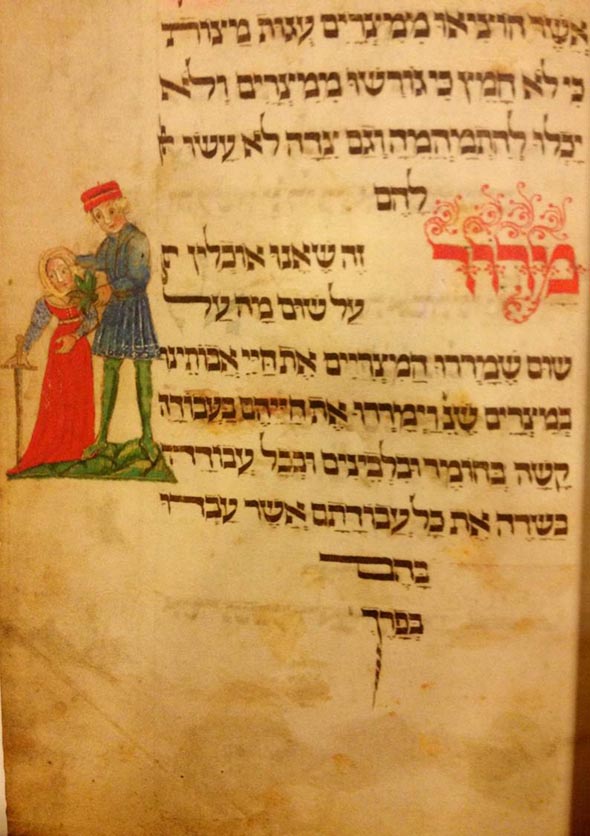

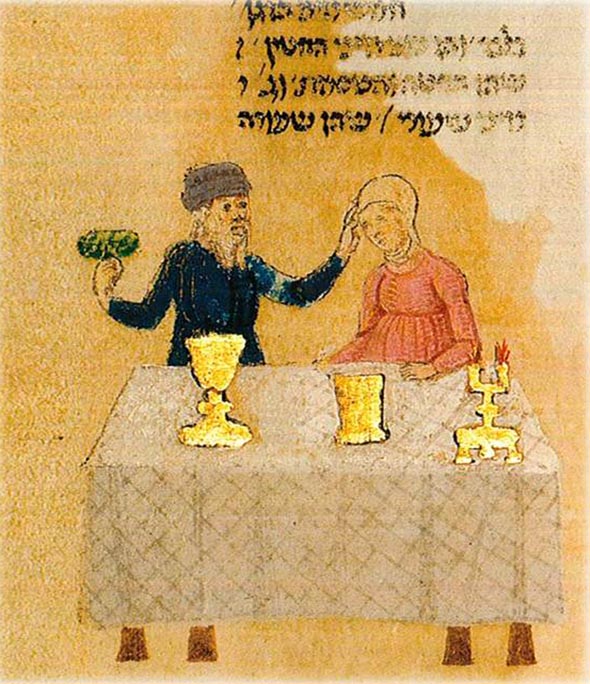

The Prague 1526 edition of the Haggadah is one of the most important illustrated haggadot ever published. It is perhaps the earliest printed illustrated haggadah for a Jewish audience and served as a model for many subsequent illustrated haggadot.[1] The earliest printed haggadah with illustration was published in 1512 in Latin and for a non-Jewish audience. That haggadah contains six woodcuts, and was intended as a response to the infamous anti-Semite Pfefferkorn’s screeds against Judaism.[2]The woodcut accompanying the first page shows three Jews around the seder who have four cups in front of them. Although the Talmud explicitly states that one is not required to have four distinct cups of wine, presumably the image is a crude method of indicating the four-fold nature of the wine during the seder rather than prescribing custom.

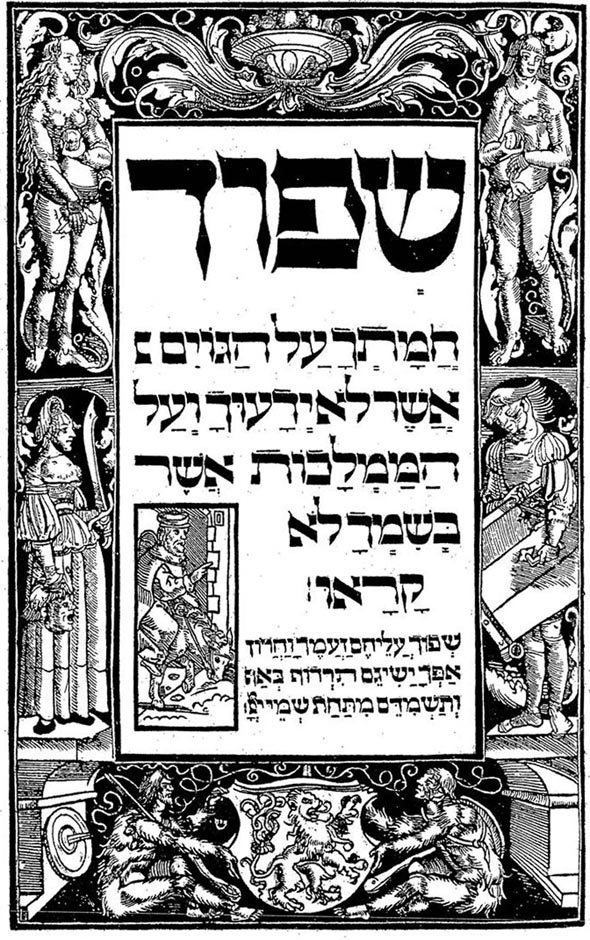

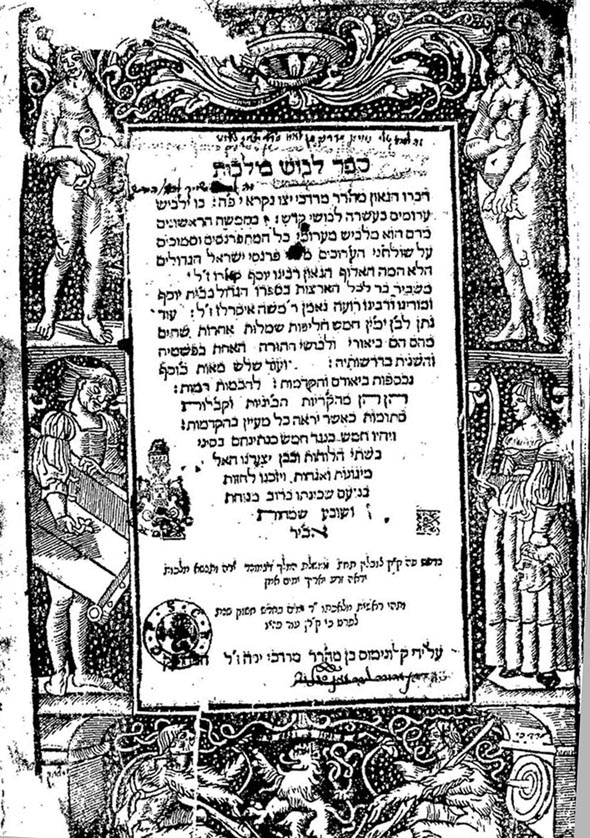

The Prague 1526 edition was published by Gershom and his brother Gronom Katz on Sunday, 26th of Tevet 5287 or December 30, 1526.[3] This detailed publication information does not appear on the title page, rather it appears at the end of the book and is referred to as a colophon. The colophon is a manuscript convention that was incorporated into earlier printed books. The Prague 1526 edition does not have a title page at all. At that time, the usage of the title page was only in its early stages.[4]

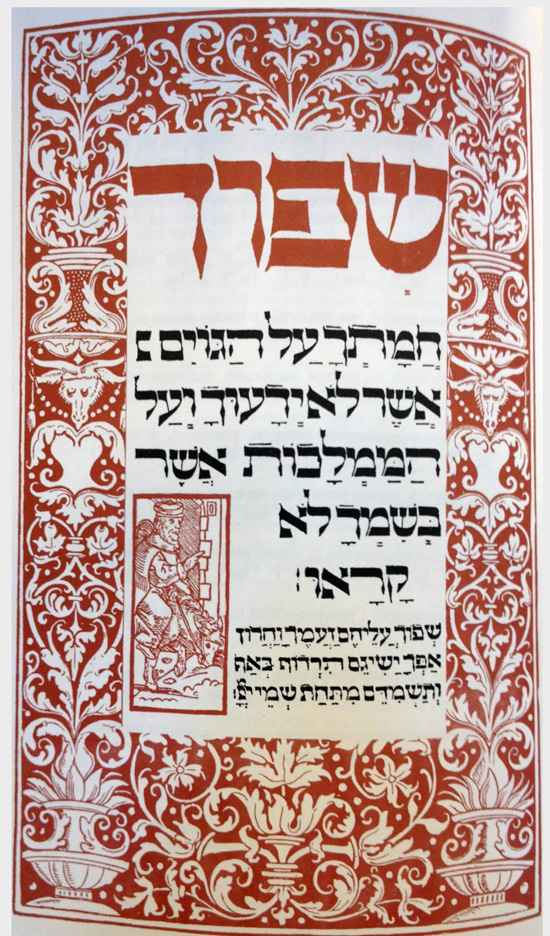

- The Earliest Hebrew Title Pages

As with non-Hebrew titles, the title page developed over time, both in terms of content as well as usage.[5] The first Hebrew title page is that of the Sefer Rokeah published in Fano in 1505.[6] But that title page is really one of the more basic forms of the title page, known as a “label title page” providing only the title and author and no other ornamentation or information.[7] In that same year, an edition of Abarbanel’s Zevah Pesach was published in Constantinople. This edition was the first to contain a border with the title and author, but no place or date of publication.[8] The first Hebrew book containing all the elements of a traditional title page, border, title, author, place and date is likely the 1511 Pesaro edition of the Talmud published by Soncino.[9]

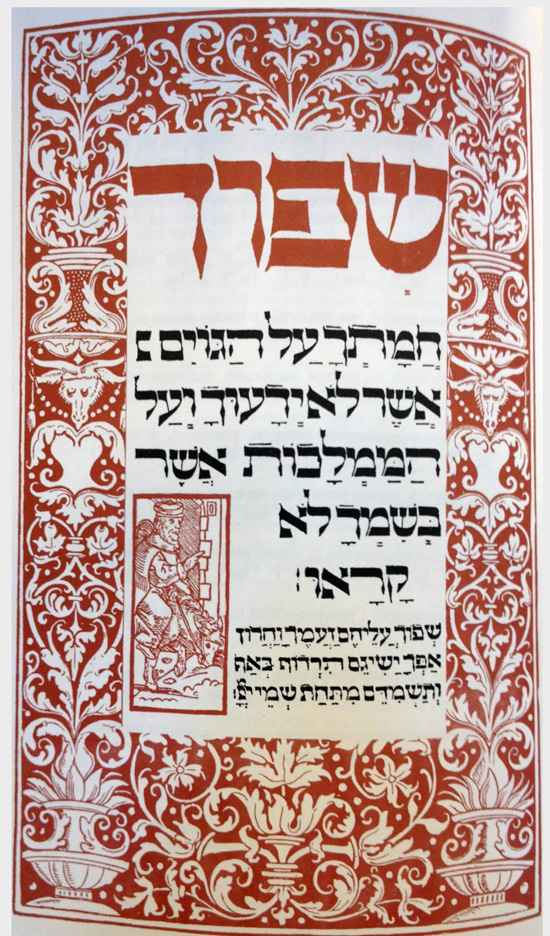

Traditionally, the Hebrew title page is referred to as a “sha’ar” or gate. The theory behind this description is that many title page borders are comprised of “gates,” the most common are the pillars that adorn many Hebrew books and are assumed to be those at Saint Peter’s Basillica in Rome. Their inclusion in Hebrew books is perhaps linked to the (discredited) notion that the Catholic Church maintains certain portions of the Jewish Temple, and these pillars were actually in the Temple. The first Hebrew book to use an architectural border is Daniel Bomberg’s edition of the Jerusalem Talmud published in 1522.[10]

- Illustrations in Hebrew Books

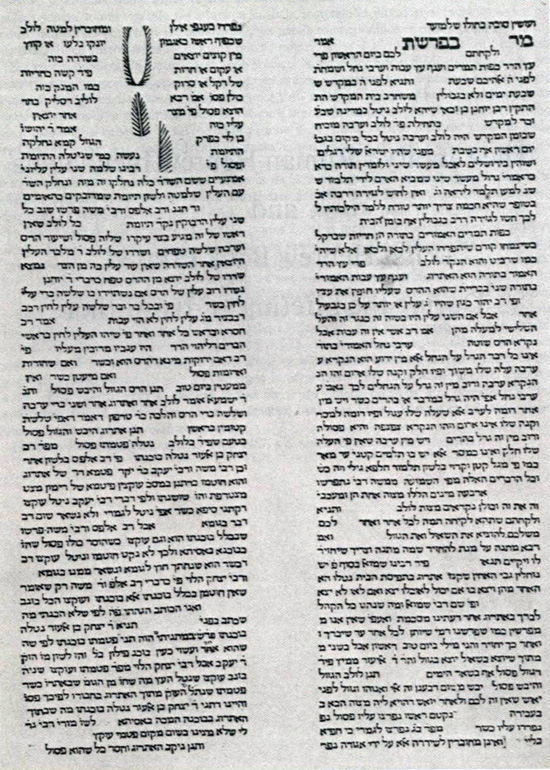

Returning to the Prague 1526 haggadah, as mentioned previously, this edition was copiously illustrated, including the first page of the book. This is not the first example of Hebrew printed illustrations. The earliest illustration to appear in a Hebrew book is that of a lulav and a handful of other explanatory images accompanying the Rome edition of the Sefer Mitzvot Gedolot dated to before 1480.[11]

The first fully illustrated Hebrew book was published in the incunabula period as well, it is Isaac ben Solomon Ibn Sahula’s Meshal ha-Qadmoni, printed in Italy, circa 1491, by Gershom Soncino.[12]

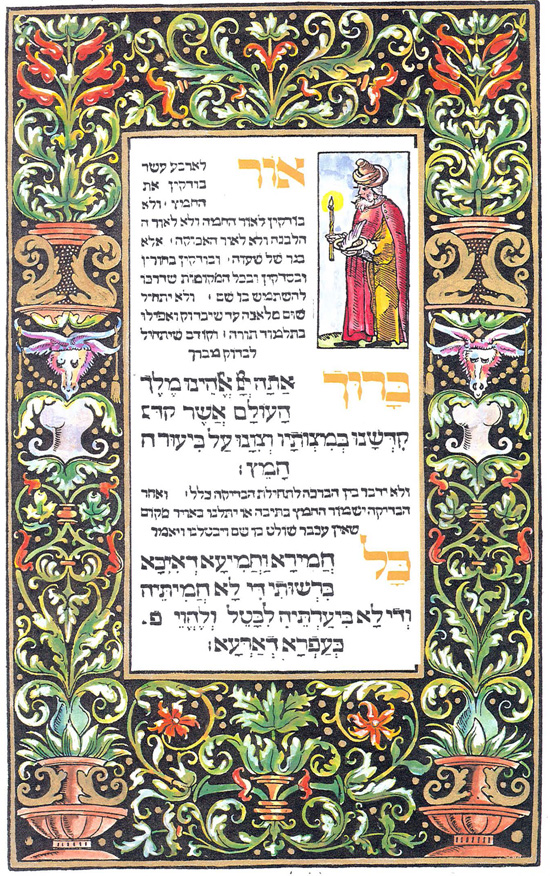

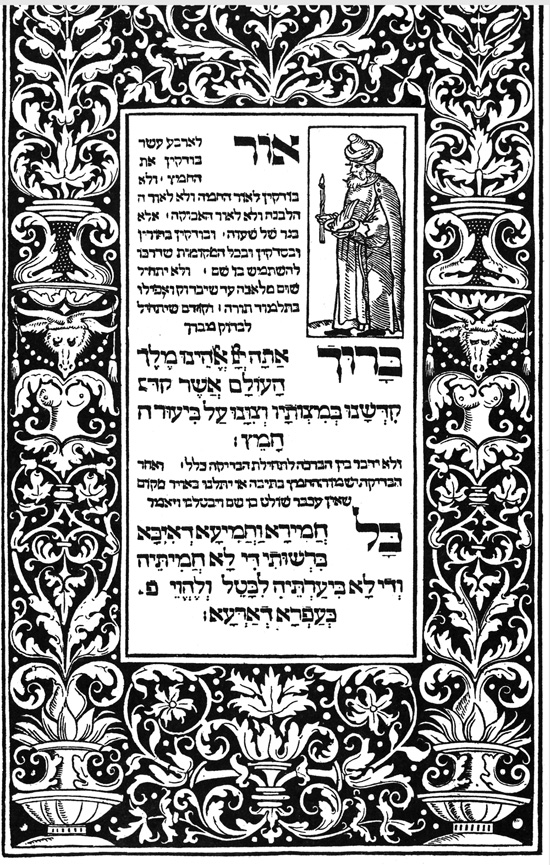

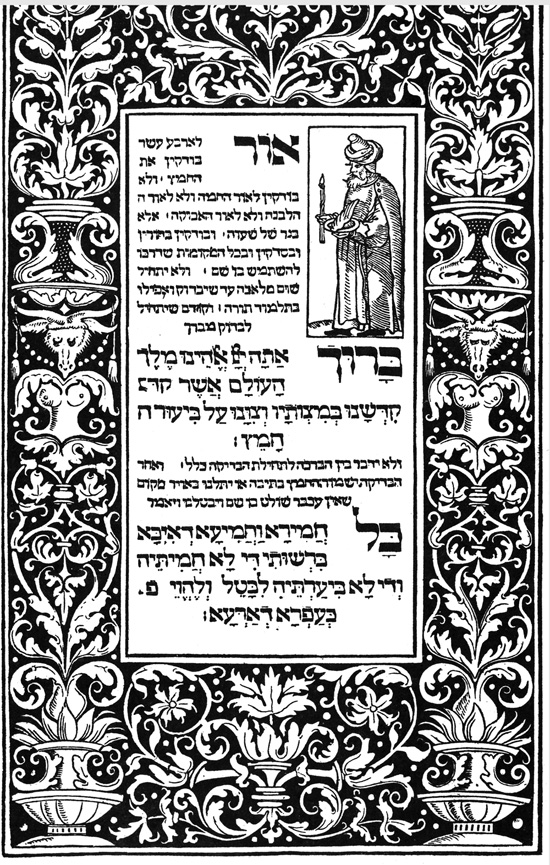

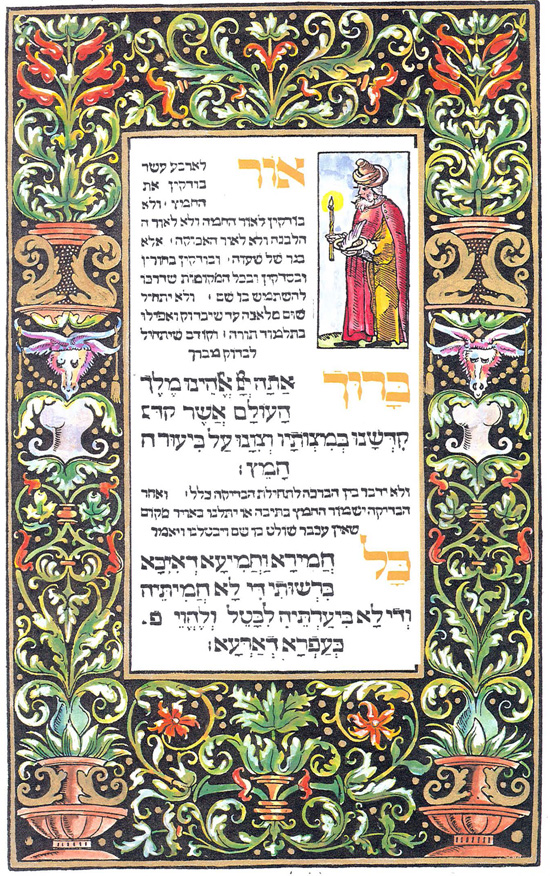

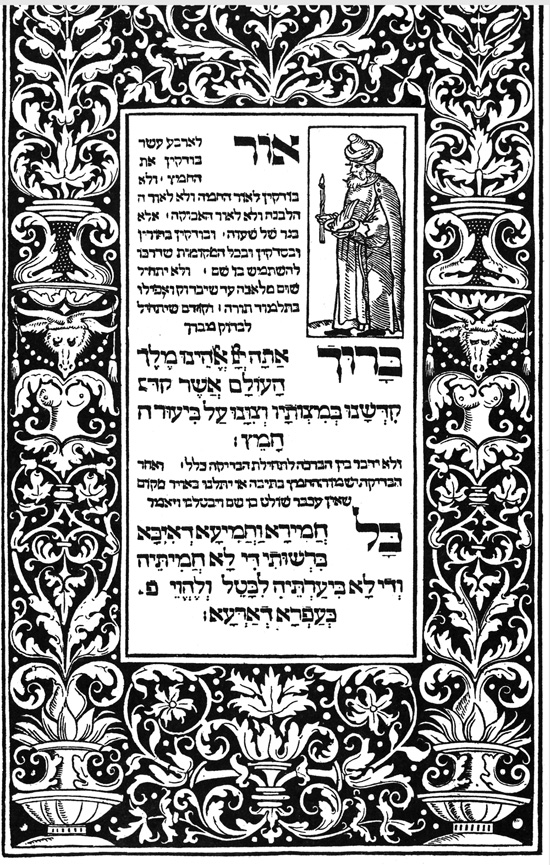

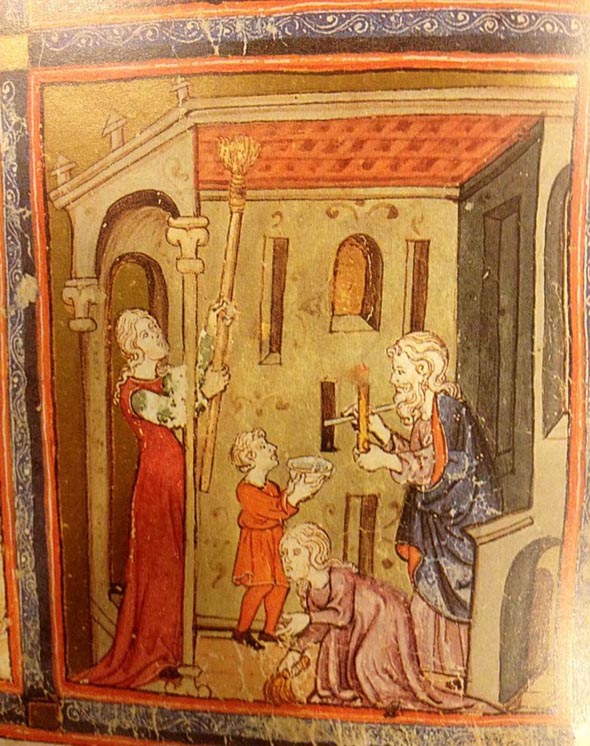

The border surrounding the first page of the Prague 1526 incorporates both Jewish as well as non-Jewish elements. First, it is obvious that a Jew had a hand in the border as, in the inset, it displays someone performing bedikat hametz (searching for the bread) where he is using the traditional implements of a candle and chicken feather. The outside border is less Jewish, and as many have noted, appears to be a copy of Italian/German renaissance borders. The two most likely candidates for models for Prague are the border first used in the 1518 edition of Sacri Doctoris by Raymond Lulli (available here) or a border first used in 1519 for Paolo Ricci’s, Lepida et litere in Augsburg and reused in an Augsburg 1522 edition of Erasmus, Ad reverendum (available here). Although we cannot pinpoint exactly which of these, if any, served as a model, what is clear is that among the images included in this border are bare-breasted women.

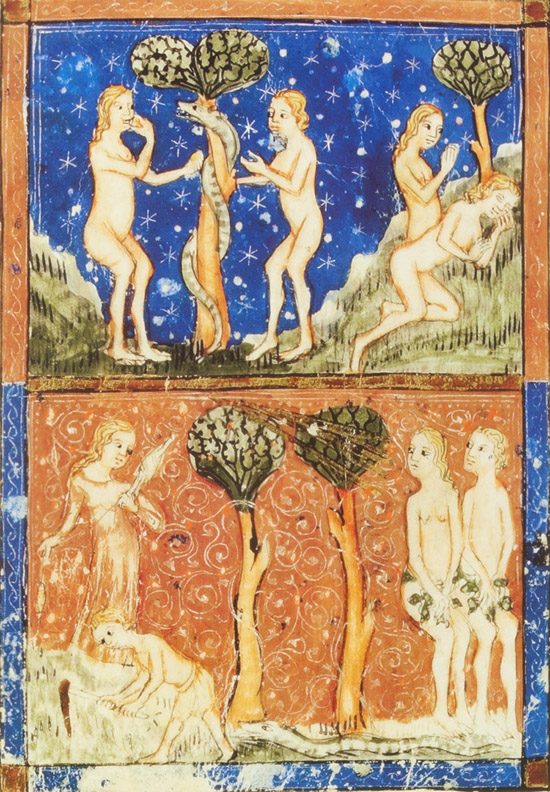

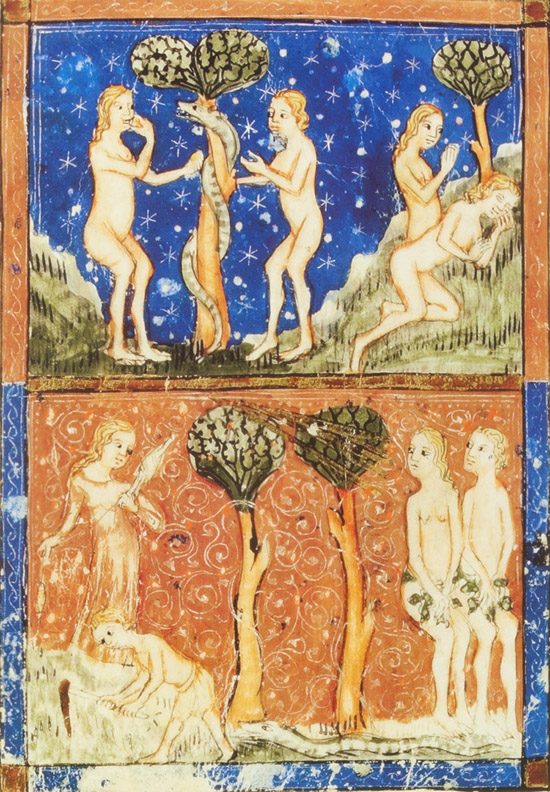

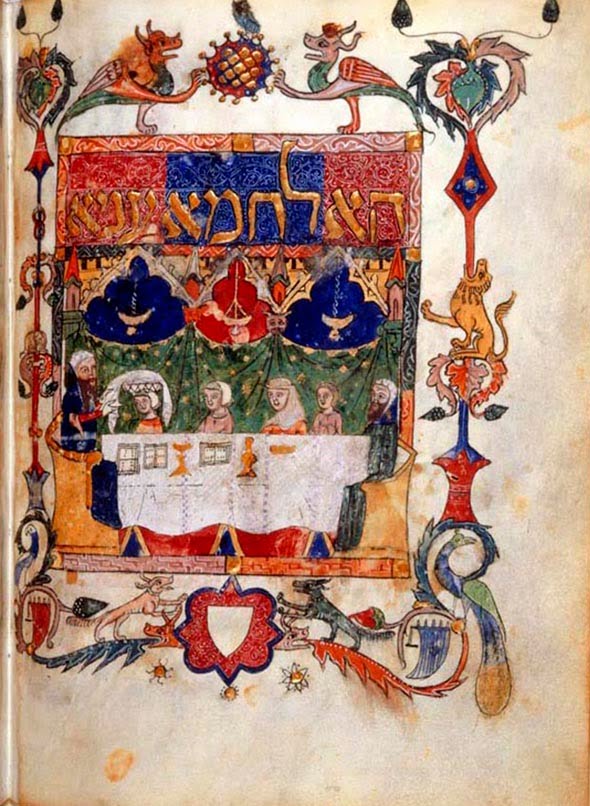

The use of bare breasted women to illustrate the haggadah is not limited to Prague. Both Charles Wengrov and Elliot Horowitz have pointed to earlier manuscript antecedents for Prague’s usage of such illustrations.[13] Aside from the printed example of the Prague 1526 Haggadah, this convention continued in manuscripts as well illuminated after 1526. There are at least four such 16th century examples.[14] Additionally, and contrary to Horwitz’s contention that Spanish Jews were less accepting of such displays,[15] the Sarajevo Haggadah, which originated in Spain around 1350, includes two panels of Adam and Eve both depicting a bare-breasted Eve.

Likewise, the Golden Haggadah, 1320 Spanish manuscript includes the same form of illustration of the Adam and Eve scene. Additionally, the Golden Haggadah includes images of nude bathers when it depicts Miriam standing from afar to see what will become of baby Moses.[16]

III. Censorship in Modern Reprints of Prague 1526

These historical antecedents notwithstanding, recent reprints of Prague 1526 have not been as accepting. This initial border has been altered to airbrush and removes the bare breasts. In 1989, a facsimile edition of Prague 1526 was published with the commentary of the Prague rabbi, Rabbi Yehuda Loew (Maharal). This border has been “touched up.”

Similarly, in 1998, a colorized facsimile edition of Prague 1526 was published. Although the publishers took great pains to provide color where before there was black and white, they also altered this border.

Oddly enough, although they found this image offensive, they decided to reproduce it in two other places in this reprint even though this image only appears once in the original. Here is the original:

Not only is the first border altered, but other instances of bare breasts have been removed; most notably the image accompanying the verse from Ezekiel 16:7 “I made you grow like a plant of the field. You grew up and developed and became the most beautiful of jewels. Your breasts were formed and your hair grew, you who were naked and bare.”

(As discussed previously here a later, Venice 1609, edition also altered this page.) Again in 2001, a facsimile of Prague 1526 “published by the Religious Council of Efrat in honor of the settlement’s twentieth anniversary . . . . two illustrations are surreptitiously deleted: the bare breasted woman” accompanying the verse from Ezekiel.[17] Most recently, in 2009, the airbrushed image of this woman was reproduced in The Schechter Haggadah: art, history; commentary.[18]

[1] There may be an earlier illustrated print haggadah, however, only 12 leaves of this haggadah are extant making it difficult to date (or identify the country of origin). For a bibliography regarding this fragment haggadah see Y. Yudlov, Otzar haHaggadot, Magnes Press, Jerusalem:1997, entry 9; and most recently, Eva Frojmovic, “From Naples to Constantinople: The Aesop Workshop’s Woodcuts in the Oldest Illustration Printed Haggadah,” in The Library, Sixth Series, Vol. XVIII, No. 2, June:1996, pp. 87-109.

[2] See R. Cohen, Jewish Icons: Art & Society in Modern Europe, University of California Press, CA:1998, pp. 21-22; see also Y.H. Yerushalmi, Haggadah; History: A Panorama in Facsimile, Philidelphia:1978, plates 6-8.

[3] Aside from the edition discussed herein, there is at least one copy of another haggadah that is also published by Cohen in Prague that same year. While both versions are substantially similar, some of the images and borders have been changed. Relevant for our purposes, is that the image accompanying “Sefokh” which is a full

page border with images of bare breasted women, has been replaced with a more innocuous border found elsewhere in the haggadah. See Yudlov, Otzar, entry 8; A. Ya’ari, Bibliography of the Passover Haggadah,

Bamberg & Wahrman, Jerusalem:1960, entry 7; Rabbi Charles Wengrov, Haggadah & Woodcut: an Introduction to the Passover Haggadah Completed by Gershom Cohen in Prague, Shulsinger Bros., New York:1967, pp. 78-9.

[4] The first Prague imprint to include a separate title page is in a 1526 edition of Yotzrot published by Cohen. See Wengrov, Haggadah & Woodcut, p. 82 n.238.

[5] Although, with regard to the adoption of the title page, Jews appear to adopt this convention at or near the time as society at large, that was not the case with other literary advances. While the majority of the western world adopted the codex and discarded the scroll some time in the third century, the first recorded Jewish reference to the codex does not occur until the late

eighth or the early ninth centuries. See Anthony Grafton, “From Roll to Codex: A Christian Initiative,” in Crossing Borders, Hebrew Manuscripts as a Meeting-place of Cultures, ed. Piet van Boxel & Sabine Arndt, Bodleian Library:2012, pp. 15-20.

[6] A.M. Habermann, Title Pages of Hebrew Books, Museum of Printing Art, Safed:1969, pp. 8-9.

[7] For a discussion of the development of the title page as well as the different types, i.e., label, border, end-title, see M.M. Smith, The Title-Page its early development 1460-1510, The British Library & Oak Knoll Press, London & Deleware:2000.

[8] See M.J. Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus, Brill, Leiden & Boston:2004, vol. I, pp. 6-7.

[9] The border used for the Pesaro Talmuds first appeared in Decachordum Christianum (The Christian Ten String Harpsichord) published in Fano, 1507 by Gershom Soncino. See M.J. Heller, Printing the Talmud, pp. 104-117 Additionally, see Heller’s discussion, id. p. 113, regarding Soncino’s reuse of the Dechachaordum‘s frames. In reality, although the frames were originally cut for Decachordum, they were first used on Gershom’s edition of Bahya ibn Pakua’s commentary on the Torah, published four months prior to Decachordum. See M.J. Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus, Brill, Leiden & Boston:2004, vol. I, p. 41; Smith, The Title-Page, supra, pp. 47-59 (discussing the use of the blank title page).

[10] See A.M. Habermann, “The Jewish Art of the Printed Book,” in Jewish Art, An Illustrated History, ed. Cecil Roth [revised ed. by B. Narkiss], New York Graphic Society Ltd., Connecticut:1971, pp. 167-68. In Habermann’s earlier work, Title Pages of Hebrew Books, p. 9, he erroneously asserts that the earliest works to include architectural title pages were Soncino’s Melitza le-Maskil and Bomberg’s Tanach, both published in 1524/25.

[11] See Joshua Bloch, “The Library’s Roman Hebrew Incunabula,” in Hebrew Printing & Bibliography, ed. Charles Berlin, New York:1976, p. 140. For a description of this work see S. Iakerson, Catalogue of Hebrew Incunabula from the Collection of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, JTS, New York & Jerusalem:2005, entry 7.

[12] See A.M. Habermann, “The Jewish Art of the Printed Book,” supra, at 169. Habermann appears to argue that this is first printed Hebrew book containing illustrations, is incorrect. As discussed above, the first was the Rome edition of Sefer Mitzvot Gedolot. He is not alone in this error. Ursula Schubert makes the same error. See Ursula Schubert, Jewish Book Art, From the Renaissance until Emancipation, [Hebrew], Kibbutz hami-Uchad, Tel Aviv:1994, p. 27. Habermann, id., notes that the great Hebrew bibliographer, Mortiz Steinschneider, was tricked with regard to one of the illustrations contained in Meshal

ha-Qadmoni. Steinschneider, in a discussion about the alleged Christian origins of these illustrations, called attention to the fact that in one of them contains a monk wearing a crucifix. But, in the interim we have learned “that this last embellishment was a

practical joke played by a Christian scholar. . . [the crucifix] having been added by [a later] hand!” Regarding the history and origins of the images included in Meshal ha-Qadmoni, see César Merchán-Hamann, “Fables from East to West,” in Crossing Borders, pp. 35-44; Ursula Schubert, Jewish Book Art, pp. 27-8.

[13] Rabbi Charles Wengrov, Haggadah & Woodcut, p. 47 nn.112-13;Elliot Horowitz, “Between Cleanliness and Godliness,” in Tov Elem: Memory, Community & Gender in Medieval & Early Modern Jewish Societies, ed. E. Baumgarten, et al., Bialik Institute, Jerusalem:2011, *38-*39.

[14] Mendel Metzger, La Haggada Enluminée, E.J. Brill:1973, plate LIV, nos. 303-305; Chantily Haggadah, Musée Condé, Ms.

732, fol. 13, reproduced in Index of Jewish Art, eds. B. Narkiss & G. Sed-Rajna, Jerusalem-Paris:1976, vol. I, card no. 36.

[15] Horowitz, “Between Cleanliness,” at *38, (“One suspects that a Spanish Jew coming to Germany in the early 15th century would have been equally surprised to see an image of a naked woman” in a Hebrew manuscript.).

[16] The Golden Haggadah, ed. Bezalel Narkiss, Pomegranate Artbooks, California:1997, figs. 17 & 24.

[17] Id. n.37. Horowitz only notes the 2001 example of censorship of Prague 1526, and apparently is unaware of the earlier

examples. Additionally, he chastises the Efrat reproduction for erroneously indicating a 1527 publication date. Efrat is not only in erring regarding the secular date. The first facsimile edition (Berlin:1925), which includes a scholarly introduction, full title

is: “Die Pessach Haggadah Des Gerschom Kohen Gedruckt Zu Prag 5287/1527.” Perhaps one can excuse the error as, in reality, it was completed on the eve of 1527, December 30, 1526.

[18] The Schechter Haggadah: Art, History & Commentary, [illustrations selected and annotated by David Golinkin], Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem:2009, p. 36, fig. 16.1.

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.