Eliezer Brodt – A Lively History of Reprinting Rabbeinu Yeruchem

Rabbi Eliezer Brodt

In recent years, a host of critical editions of works on various rishonim have been published on all topics – some seeing the light of day for the very first time – on topics related to halakha, kabbalah, and chiddushim on the Talmud. These works have been made available via the major printing presses such as Mossad HaRav Kook, Machon Yerushalyim, Machon Talmud Yisraeli, Machon Harry Fischel and others.[1] However, one very important work has noticeably been omitted from being reprinted, except for a photomechanical off-set of the second printing. This work is Sefer Toledot Adam ve-Chava and Sefer Meisharim, the halakhic works of Rabbeinu Yeruchem Meshullam (c. first half of the 14th century) who was a student of R. Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), R. Shlomo ben Aderet (Rashb”a), and R. Abraham ibn Ismaeil – author of Chiddushei Talmid HaRashb”a on Baba Kamma. In this post I would like to discuss the story behind why it was never retype-set, until a few weeks ago.

Rabbeinu Yeruchem authored his works many years ago, in years of the range of צד (1334). He was a student of the Rosh and his works are quoted extensively by the Beit Yosef throughout Tur and Shulhan Arukh. The Maggid (an angel who learned torah with the Beit Yosef) of the Beit Yosef told him ואוף ירוחם טמירי רחים לך אע”ג דאת סתיר מלוי בגין דמלאכת שמים היא (מגיד משרים פרשת צו).

Rabbeinu Yeruchem’s work contains three parts one called Meisharim and the remaining two parts entitled Toledot Adam ve-Chava. The part Adam contains everything relating to the man from birth until marriage; whereas Chavah contains everything from after marriage until death. This work was first printed in Constantinople in רעו (1517) and is extremely rare; only two complete copies are known to be extant. It was reprinted a second time in שיג (1553) in Venice; this is the version available today in photomechanical off-set editions. But, the Chida already notes that “this edition is full of mistakes.”[2] He also writes that he saw a manuscript of this sefer and was amazed as to the large amount of missing text as well as gross errors in the printed edition. The question remains as to why this work was never retype-set as opposed to the works of other Rishonim?

The answer might be found in the words of the Chid”a[3] where he brings as follows:

שמעתי מרבנן קשישאי בעיר הקודש ירושלים שקבלו מהזקנים דספר העיטור וספר רבינו ירחום הם מבחינת סוד עלמא דאתכסיא וכל מי שעושה באור עליהם או נאבדו הביאור או ח”ו יפטר במבחר ימיו”I have heard from old Rabbi in the holy city of Jerusalem that they have a tradition that the books, Sefer haIttur and Sefer Rabbeinu Yeruchum, they are a high secret and anyone who writes a commentary on these books either the work will be lost or they will die in the prime of their life.

He than goes on to list a few people who started working on expounding the sefer, and either died in middle or the work was lost. In a different place the Shem Hagedolim brings the words of the Maggid to the Beit Yosef in the Maggid Meisharim (end of parashat Vayakhel) where he writes as follows:

וכן במאי דדחית מילוי דירוחם טמירי שפיר עבדת וכן בכל דוכתא דאת משיג עליה יאות את משיג עליה וקרינא ליה ירוחם טמירי דאיהו טמיר בגינתא דעדן דאית צדיקייא דלא משיג זכותא דילהון למהוי בגינתא דעדן בפרסום אלא בטמירו אבל במדריגה רבא ויקירא איהו

This, says Professor Meir Benayahu, is the reason why there is a curse on retype setting the work. What is not understood is that this is a completely halakhic work, not kabbalistic in any way, so why was there such a curse?[4]

One such work, which the Chida already mentions, is R. Hayyim Algazi’s Netivot Hamishpat.[5] The title page already records with regard to R. Algazi, “תנוח נפשו בעדן” (may his soul rest in heaven) intimating he died in the process of writing this commentary.

Another work in this category is that of R. Reuven Chaim Klein’s Shenot Chaim.[6] Unfortunately, he also died amidst writing the sefer, at the age of 47. The title page also records that the author did not want his name to appear, one can suggest that perhaps he thought if his name did not appear, he would not be subject to the curse. What’s interesting to note is in the haskamah of R. Joseph Shaul Nathenson, author of Shu”t Shoel u-Meshiv, to R. Klein’s work, as he makes no mention of any cherem to this work, but does quote the Maggid Mesharim cited earlier. Additionally, R. Chaim Sanzer, in his haskamah to this sefer, makes no mention of any cherem.

The other work which the Chidah brings was under this curse was the Sefer HaItur. This sefer was privileged to be reprinted with a critical edition by the great R. Meir Yonah, who called the glosses ‘Shar Hachadash and Pessach Hadiveir.’ Dr. Binyamin Levine, author of the Otzar Hagaonim series, writes in his short biography on him – as he used this work in many his own seforim – that he also suffered many tragedies; i.e. he lost many children.[7]

Interestingly enough, I found a nice size work on Rabbeinu Yeruchem and the author did not die young. His name was R. Yehudah Ashkenazi (1780-1849) the work is called Yisa Bracha (available at HebrewBooks.org), printed in Livorno 1822. He authored many famous seforim such as the Geza Yeshai (klallim) (Livorno, 1842), Siddur Beit Oved (Livorno, 1843), Siddur Beit Menucha (Livorno, 1924), Siddur Beit HaBechirah (Livorno, 1875), and Siddur Shomer Shabbat (Livorno, 1892).

In spite of all the above, a portion of the Rabbeinu Yeruchum has now been printed based of the first printing as well as manuscript, by on R. Yair Chazan.

Based on the above, we find ourselves asking the question ‘why did this R. Yair Chazan decide to reprint this work?’

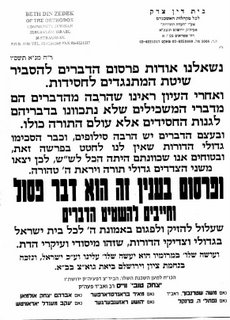

The answer is found in the haskamah to the sefer from R. Ovadiah Yosef, who wrote that the whole curse is only if one is writing a pairush/commentary – expository text – on the work. But if one’s whole intent is to just fix the printing mistakes, which is R. Chazan whole intention here, it’s not a problem. Besides for the haskamah of R. Ovadiah Yosef, there are a few other haskamot; amongst them R. Shmuel Auerbach and R. Chaim Pinchus Scheinberg.

Just to give a brief overview of this work, as mentioned before the earlier editions of the Rabbeinu Yeruchem are full of printing mistakes and is missing many pieces. What R. Chazzan did was to track down the existing manuscripts of the sefer and try to fix the mistakes and put in the missing pieces. He also puts in the sources of Rabbeinu Yeruchem and he brings down where it is quoted in various poskim. He retype-set it beautifully making it a pleasure to read and use in compared to the old print.

So far only the third volume (the חוה section) has been printed I hope to see the rest of R. Yerucham printed soon.

Notes:

[1] See here for Marc B. Shapiro’s appreciation for R. Yosef Buxbaum, founder and director of Machon Yerushalayim, posted at the Seforim blog.

[2] Shem Hagedolim, Mareches Gedolim, letter yud, number 382, quoting the Ralbach, (siman 109); see also R. Chaim Shabtai HaKohen, Shu”t Mahrch”sh, Even HaEzer p. 153,b (“it is already known that the book of Rabbenu Yeruchum has many errors and unnecessary wordage”); R. Y. Sirkes, Bach Y.D. no. 241 s.v. U’mah Sechatav Avor Aviv (“I have already studied this work [Rabbenu Yeruchum] and it is full of error – too many to count”); Y.S. Speigel, Amudim B’Tolodot Sefer HaIvri : Hagahot U’Magimim p. 247 n.121 for additional sources.

[3] idem.

[4] Pirush Sifri, Rabbenu Eliezer Nachum, Meir Benayahu, ed., (Jerusalem, 1993), Introduction.

[5] (Istanbul, 1669; reprinted by Pe’er HaTorah in Yerushalyim, circa 1975)

[6] (Lemberg, 1871; reprinted by Machon Yerushalayim, Jerusalem, 1985)

[7] Binyamin Levin, Mesivos: Talmud Katan leSeder Mo’ed, Nashim, u-Nezikin (Jerusalem, 1973), end of this book.