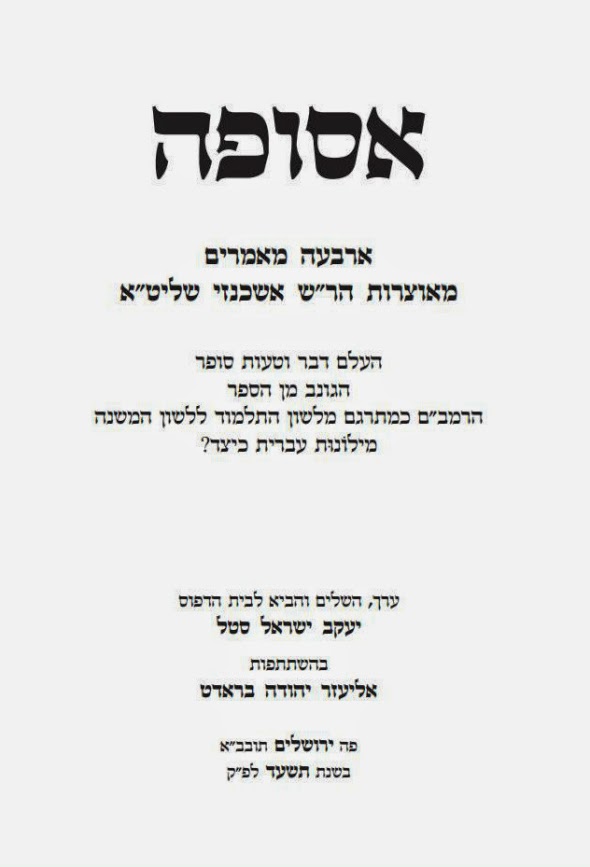

Book week 2014

week 2014

Eliezer Brodt

Eretz Yisrael. As I have written in previous years every year in Israel, around

Shavous time, there is a period of about ten days called Shavuah Hasefer – Book

Week (see here, here, here here, here here and here).

advantage of this sale as a law was passed recently against sales on newly

published books, for the first 18 months after the book was published, except

for book week. Many of the companies offer sales for the whole month. Shavuah

HaSefer is a sale which takes place all across the country in stores, malls

and special places rented out just for the sales. There are places where

strictly “frum” seforim are sold and other places have most of the secular

publishing houses. Many publishing houses release new titles specifically at

this time.

title if I just noticed the book. As I have written in the past, I do not

intend to include all the new books. Eventually some of these titles will be

the subject of their own reviews. I try to include titles of broad interest.

Some books I cannot provide much information about as I just glanced at them

quickly. Some books which I note, I can provide Table of contents if requested,

via e mail.

although book publishing in book form has dropped greatly worldwide, Academic

books on Jewish related topics are still coming out in full force.

am offering a service, for a small fee to help one purchase these titles (or

titles of previous years). For more information about this email me at

Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the

efforts of the the Seforim Blog.

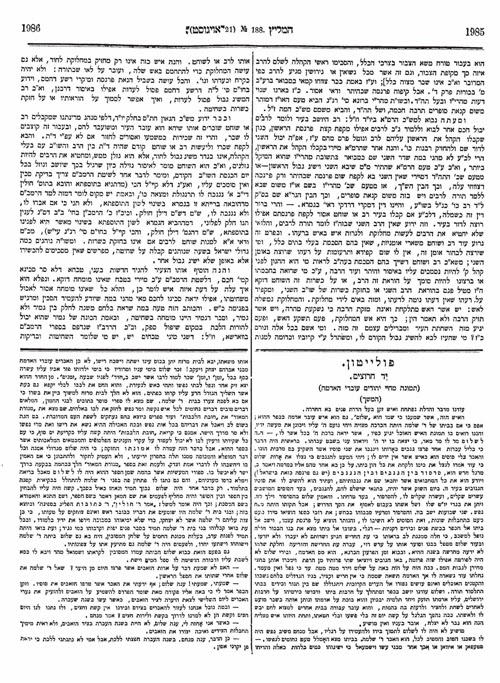

במרוקו, 420 עמודים

לאהרן, ספר היובל לכבוד ר’ אהרן ליכטנשטיין, הוצאת בר אילן, 304 עמודים

קירשנבום, ריהוט הבית במשנה, הוצאת בר אילן, 342 עמודים

בירושלים, קרות שכונות בית ישראל וסביבתה בכתביו של ר’ משה יקותיאל אלפרט

[1938-1952], בעריכת פינסח אלפרט ודותן גורן, הוצאת אוניברסיטת בר אילן,414 עמודים

אופיר שמש, חומרי מרפא בספרות היהודית של ימי הביניים והעת החדשה, פרמקולוגיה,

היסטוריה והלכה [מצוין], הוצאת בר אילן, 655 עמודים.

הכתר, מהדורה מוקטנת, יחזקאל

הכתר, פורמט גדול, שמות ב

קובץ מחקרים שי ליוסף הקר, , [מצוין], [ניתן לקבל תוכן ענינים], 596 עמודים

דן, תולדות תורת הסוד העברית, ט, 535 עמודים,

תורת הסוד העברית, י, 504 עמודים

בית צ’רנוביל ומקומו בתולדות החסידות, 472 עמודים

קליבנסקי, כצור חלמיש, תור הזהב של הישיבות הליטאיות במזרח אירופה [מצוין], 550

עמודים, [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים]

ריינהרץ, חמוריות, מסע בעקבות החמור, מיתולוגיה, אלגוריה, מליות וקלישאה, 202 עמודים

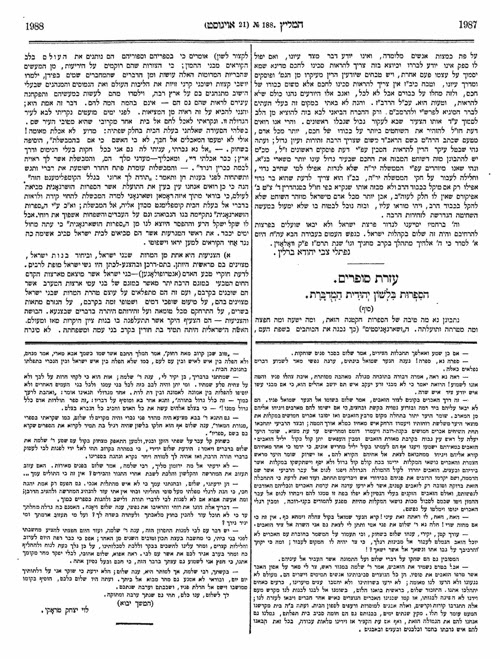

booth there are some otherwise hard to track down books, related to Poland from

Tel Aviv University available for some reduced prices amongst the titles of

interest are;

זיכרונות יחזקאל קוטיק דוד אסף (מהדיר) שני חלקים

פירוש רש”י למסכת ראש השנה, מהדורה ביקורתית, מהדיר אהרן ארנד, מוסד ביאליק,

ספר אלימה לר’ משה קורדובירו ומחקרים בקבלתו, אוניברסיטת בן גוריון, 262 עמודים.

נוסח המקרא, מהדורה שנייה מורחבת ומתוקנת, נ+411+32 עמודים

פרידמן, לתורם של תנאים, אסופות מחקרים מתודולוגיים ועיוניים, ביאליק, 534 עמודים

[מצוין], [ניתן לקבל תוכן העניינים].

בדיון ומציאות בספרותנו, מוסד ביאליק

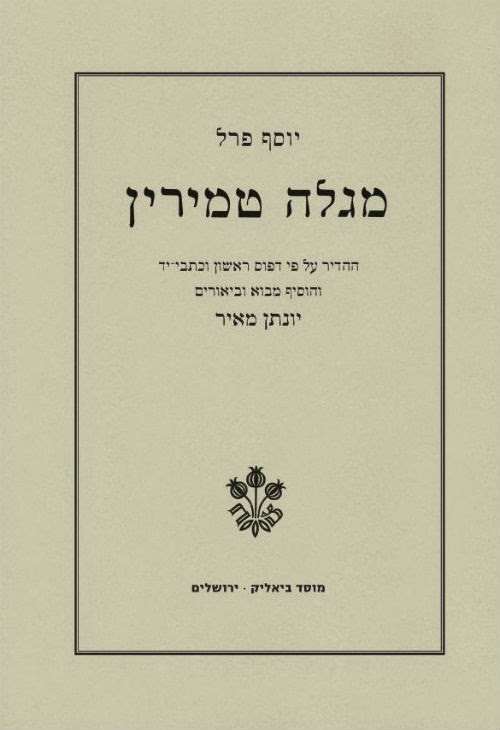

דפוס ראשון וכתבי-יד והוסיף מבוא וביאורים יונתן מאיר, מוסד ביאליק. ג’

חלקים. כרכים ‘מגלת טמירין’ כולל 345 עמודים +מח עמודים; כרך ‘נספחים’ עמ’

349-620; כרך ‘חסידות מדומה’ עיונים בכתביו הסאטיריים של יוסף פרל, 316

עמודים.

עופר יהונתן יעקבס, 718 עמודים, [מצוין] [ראה כאן]

214 עמודים

קורן, 264 עמודים [מלא חומר מעניין].

ישובות הר עציון.

כב [ניתן לקבל תוכן העניינים]

תפילה ומנהגי תפילה ארץ-ישראליים בתקופת הגניזה’ [מהדורה שניה] כריכה רכה.

לר’ משה בן יהודה חלק א מאמרים א-ז, איגוד העולמי למדעי היהדות, [מהדיר: אסתי

אייזנמן], 355 עמודים

חן לר’ לוי בן אברהם, מעשה מרכבה, מכ”י, ההדיר והוסיף מבוא והערות חיים

קרייסל, האיגוד למדעי היהדות, 330 עמודים , [כרך שלישי מתוך החיבור] [ניתן לקבל

תוכן העניינים].

נזיקין, נוסח מונחים מקורות ועריכה, בעריכת מנחם כהנא, מגנס, 392 עמודים

ההיסטוריה דמות העבר היהודי במאה העשרים, מגנס, 388 עמודים

המשכילים במדעים חינוך יהודי למדעים במרחב דובר הגרמנית בעת החדשה, מגנס 243

עמודים

יעוף וכדיבוק יאחז, על חלומות ודיבוקים בישראל ובעמים, מגנס

א, [מצוין] [ניתן לקבל תוכן], 216 עמודים

העברית בירושלים, כרך ד

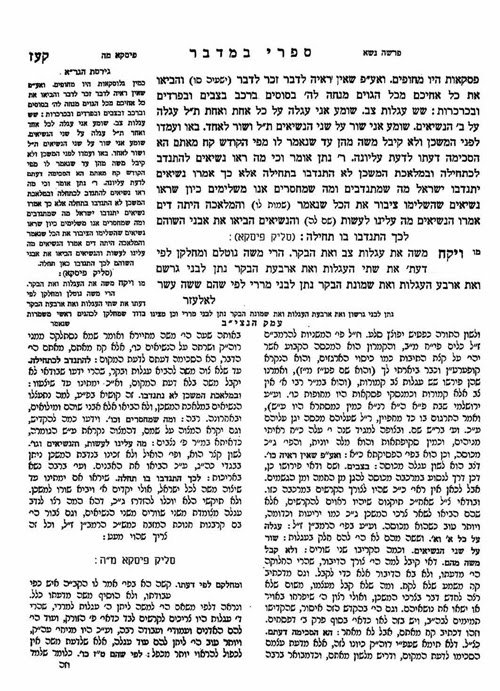

Abrams, Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual

Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism (second edition), 820 pp. (updated)

מסכת סוכה, פרקים ד-ה, משה בנוביץ, 802 עמודים

הרמב”ם, ג’ חלקים יהושע בלאו, עם הוספות רבות

Ben Tzvi:

בין גבולות, תחומי ארץ ישראל בתודעה היהודית בימי הבית השני, ובתקופת המשנה

והתלמוד, 348 עמודים, [מצוין]

השלישי [מאה העשירית] ב’ חלקים, מהדירים: יוסף יהלום, נאויה קצומטה, בן צבי, 1139

עמודים

ישראל במקורות ערביים בימי הביניים (643-1517) אסופות תרגומים, 571 עמודים

הרמב”ם במזרח, איגרת ההשתקה על אודות חיית המים ליוסף אבן שמעון, שרה סטרומזה

[מהדורה שניה] (כריכה רכה), 170 עמודים

הודו, ד, שני חלקים, מכתבים של חלפון הסוחר עם המשורר ר’ יהודה הלוי, כולל ניתוח

חשוב של כל המכתבים מאת מרדכי עקיבא פרידמן [מצוין],

עולם, שני חלקים, [מצוין] מהדורה פירוש ומבוא, חיים מיליקובסקי

שיש, כתובות מבתי החיים של פדובה 1529-1862 דוד מלכיאל

רייך, מקוואות טהרה בתקופות הבית השני המשנה ותלמוד

קימרון, מגילות מדבר יהודה, כרך שני החיבורים העבריים

רפפורט, בית חשמונאי, עם ישראל בארץ ישראל בימי החשמונאים, 499 עמודים.

ומלואה, חלק ב, מחקרים בתולדות קהילת ארם צובה (חלב) ותרבותה, 250+ 62 עמודים

אורתודוקסיה הומאנית, מחשבת ההלכה של הרב פרופ’ אליעזר ברקוביץ, ספריית הילל בן

חיים, 475 עמודים

מאכל תאוה, מזון ומיניות בספרות ההשכלה, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 195 עמודים

המשמעות הסמלית של היין בתרבות היהודית, ספריית הילל בן חיים, 184 עמודים

המכשף היהודי משואבך, משפטו של רב מדינת ברנדנבורג אנסבך צבי הריש פרנקל, ספריית

הילל בן חיים, 211 עמודים

[מהדיר] שרידי תשובות מחכמי האימפריה העות’מנית, חלק ג

ישראל בעל שם טוב ובני דורו, שני חלקים, 686 + 727 עמודים

הויכוח, ויכוח על חכמת הקבלה ועל קדמות ספר הזוהר, וקדמות הנקודות והטעמים,

כרמל,41+ 142 עמודים

[פורסמה תגובה של בנימין בראון למאמר הביקורת של פרופ’ שלמה זלמן הבלין

שפורסמה בגליון הקודם של קתרסיס, וגם תגובה של שלמה זלמן הבלין לתגובה של בראון]

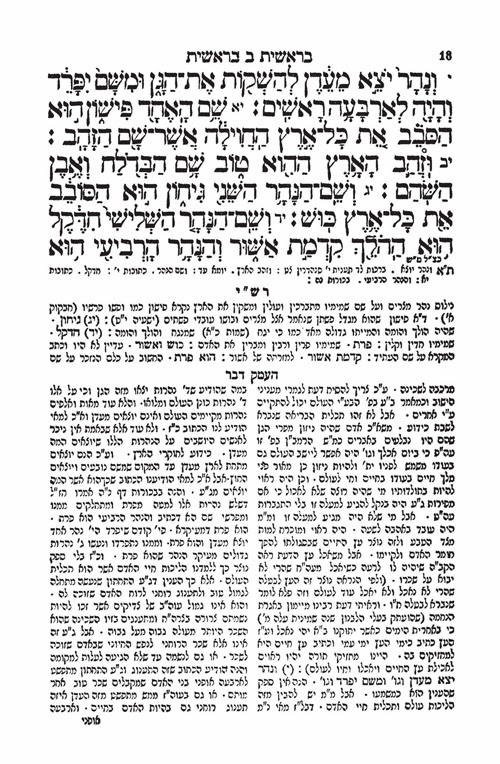

Sciences:

to Hebrew manuscript collections, Second revised edition, Israel Academy of

Sciences and Humanities, 409 pp. [TOC available]

ליכטנשטיין, מנחת אביב, חידושים ועיונים בש”ס, 659 עמודים

Jermiah, The fate of a Prophet, Maggid- Koren, 225 pp.

Mo’adim, Understanding the laws of the Festivals, Maggid-Koren, 753 pp.

Philosophical Quest of Philosophy, Ethics, Law and Halakhah, Maggid-Koren,

434 pp. [Excellent]

Laws of Cooking and Warming Food on Shabbat, 194+285 pp.

Rebbe, 246 pp.

הכהן קוק, לנובכי הדור [מצוין] מכתב יד, כולל מבוא והערות

עד היום הזה, ידיעות ספרים, שאלות יסוד בלימוד תנ”ך [מלא חומר חשוב],

470 עמודים

שחור כחול לבן

מכתבים של ר’ משה נריה לאשתו

מקום בפרשה, גיאוגרפיה ומשמעות במקרא, ידיעות ספרים, 480 עמודים, [מציון]

בעקבות הזמן היהודי, הפילוסופיה של לוח השנה, ידיעות ספרים, 383 עמודים

works at book week:

שמואל וזאב ספראי, שביעית מהדורה שניה

שמואל וזאב ספראי, דמאי, 293 עמודים

שמואל וזאב ספראי, מעשרות ומעשר שני, 460 עמודים

אבות, זאב ספראי, 390 עמודים

sale this week. Here is a list of some of their newer titles:

ר’ יוסף חיים בעל ספר בן איש חי, שו”ת תורה לשמה, מכתב יד קדשו,

כולל הערות ומבוא מקיף על הספר, מכון אהבת שלום, תרפח עמודים.

סידור

אור השנים, לבעל הפרד”ס, ר’ אריה ליב עפשטיין, אהבת שלום, תתקצג עמודים

מכתב

מאליהו, שאלות של ר’ יוסף חיים בעל ‘בן איש חי’ לר’ אליהו סלימאן מני, עם הערות של

ר’ יעקב הלל, רצא עמודים

שבחי

האר”יהאר”י וגוריו כתבוני לדורות, ג’ חלקים, מהדורה רביעית

מן

הגנזים, ספר ראשון, ‘אוסף גנזים מתורתם של קדמונים גנזי ראשונים ותורת אחרונים

דברי הלכה ואגדה, נדפסים לראשונה מתוך כתב יד,

תטז עמודים

מן

הגנזים, ספר שני, ‘אוסף גנזים מתורתם של קדמונים גנזי ראשונים ותורת אחרונים דברי

הלכה ואגדה, נדפסים לראשונה מתוך כתב יד,

תיח עמודים

תלמוד

מסכות עדיות, למהר”ש סיריליאו, על פי כ”י, אהבת שלום, 73 + שיג עמודים

[מצוין]