A Picture is Worth a Thousand Questions – Part II

The classic Vilna Shas, published by the firm of the Widow and Brothers Romm, was completed during the years 1880-86. It was the most complete and accurate edition of the Talmud printed until that time, containing many new Peirushim and using new sources to ensure the accuracy of text. This fact was not lost on the chief editor Shmuel Shraga Feiginsohn as he states in the famous Achris Davar at the end of Maseches Nidah.

“We did not print a Shas like every other Shas,… by copying what came before us like a monkey. We wanted to create something entirely new and to illuminate it with an entirely new light”

My purpose here is to concentrate on one small Sugya in Shas , the commentary of Rashi on it, with the accompanying diagrams in the Vilna edition. I will then show diagrams from some previous editions of the Talmud that are more illustrative and more accurate. Perhaps the reader will then conclude that there were some portions of previous editions that the Vilna Shas should have copied rather than the one that it did.

The Gemara on Yoma 11b discusses doorways that are or not required to have a Mezuzah. It then discusses one type of doorway for which there is a Machlokes between Rav Meier and the Rabbanan and that is the so called Shaar Madai. As Rashi there explains it, a Shaar Madai is a gate in the wall of a city which has within it an arched doorway (Kipah) and was used commonly in Madai. For our own purposes, think of the Shaar Yafo which is substantive structure in itself and within it is the actual doorway into the old city.

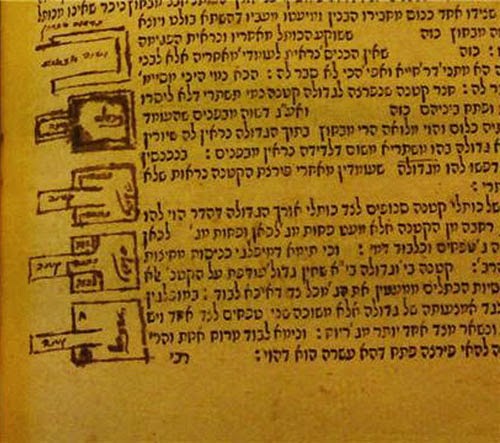

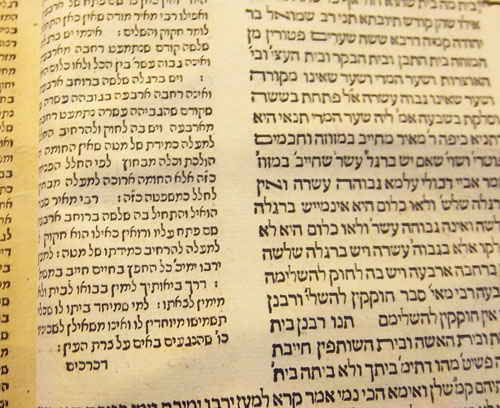

As a bit of background, for a doorway to require a Mezuza it needs to have three elements. It has to be at least four Tefachim wide on the bottom and the top, it’s side posts ( Raglayim) have to be ten tefachim high, and it has to have a lintel on top. The Gemara states that the only case of Shaar HaMadia where there is disagreement in Halacha between Rav Meier and the Rabbanan is this: The doorway starts with a width of 4 Tefachim on the bottom, each side of the doorway ( Regel) rises up straight at least 3 Tefachim so that at that point there are still 4 Tefachim between them, but then the doorway starts curving inwards, rising on each side to a height of 10 Tefachim. However, at that point, there is no longer 4 Tefachim in width between the two sides. Rav Meier says that if the gate structure( the Chomah) itself is at least 4 Tefachim wide at a height of at least 10 Tefachim, we apply the concept of “Chokekin L’Hashlim” to this case. Chokekin L’Hashlim is a Halachic concept which literally means that we “excavate to complete ( the required measurement)”.Rav Meier says that if the walls surrounding the archway are thick enough that had they been excavated, the doorway could be made 4 Tefachim wide for a height of ten Tefachim, then the doorway requires a Mezuzah. The Rabbanan disagree and say that even this type of Shaar Madai does not require a Mezuzah.

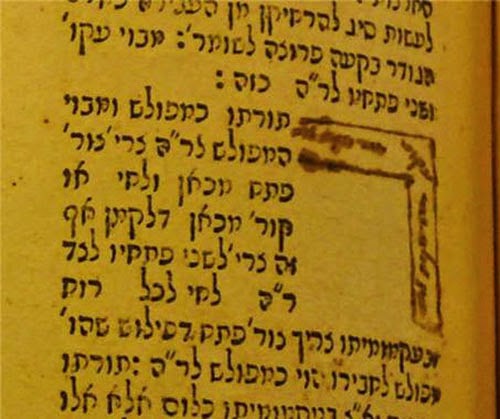

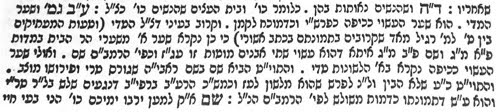

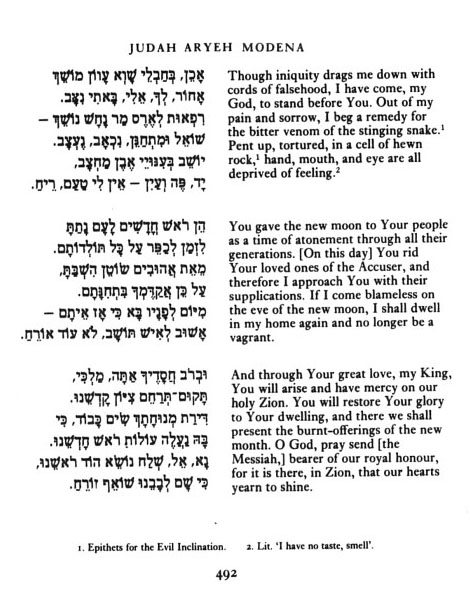

Let’s go through the Rashi: “V’Yaish B’Ragleha Shlosha” “The sides of the doorway rise up ( at least) three (Tefachim)”….still maintaining a width between them of four Tefachim….but the width between them is not four Tefachim at the height of ten Tefachim…because before the sides rise to the height of ten Tefachim, they narrow to a width of less than four Tefachim…but you can expand the emptied out space contained in the encompassing structure ( The Chomah) to the width on the bottom ( 4 Tefachim)… for the gate structure does not parallel the inner doorway like this (“Kazeh”)…rather the wall ( meaning the gate structure)is longer on top than the doorway opening like this (“Kazeh”)

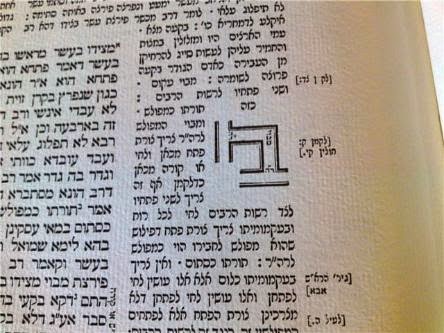

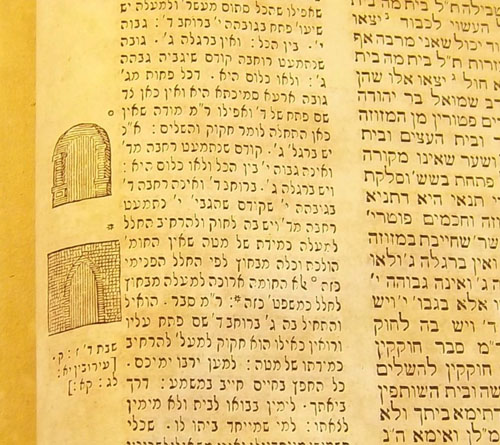

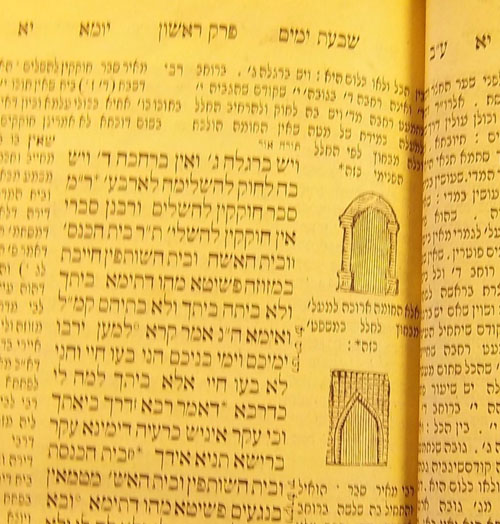

There are very nice diagrams of the two possibilities mentioned by Rashi in the 1829-1831 edition of the Shas printed in Prague by Moshe Yisrael Landau, grandson of the Nodah B’Yehudah.

It is very clear from the diagrams that the first possibility mentioned by Rashi ( the one that is not referred to in the Gemara) is where both the doorway and gate structure curve inwards so that neither of them has a width of 4 Tefachim on top. The actual case discussed by the Gemara ( the second possibility of Rashi) is where the doorway curves in to be less than four Tefachim on top, but the gate structure itself retains at least the width of four Tefachim on top and is also straight on top.

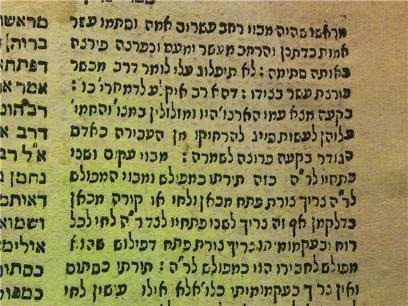

Similar diagrams appear in the Lemberg small and large folio editions of 1862, and the Vienna edition of 1841. Here is what the small folio version of the Lemberg edition looks like.

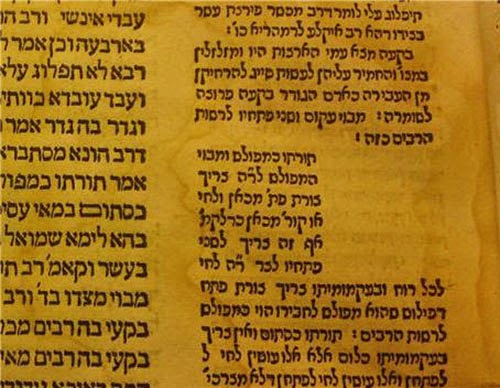

Before we take a look at the diagrams presented in the Vilna Shas, let us look at these diagrams in much earlier editions so we can trace their development. The only manuscript copy of Rashi that I was able to obtain (courtesy of Dr. Ezra Chwat at Hebrew University) looks like this.

The first thing you notice is that this manuscript does not have the word “Kazeh” after the first case, rather just referring to the second case. The illustration for the second case shows a curved doorway within a rectangular structure, exactly the way we have seen it in the Prague, Vienna and Lemberg editions. This illustration also seems to indicate that the sides of the inner doorway must be at least 10 Tefachim high before curving inwards. The words “Ragleha Asarah” are inside the doorway structure making it appear that they apply to the sides of the doorway being ten Tefachim before they curve inwards. This seems to be the case where even the Rabbanan agree that a Mezuzuah is needed. The diagram goes against Rashi’s Lashon here which is “She”kodem She’Higbiah Asarah,Nisma’et Rechava Mi’Daled”.

Advancing to the printed edition, we first look at Bomberg 1521.

The Bomberg scholars must have had a Rashi manuscript which had the word “Kazeh” after both the first and second case in Rashi. However, they did not leave any room for it to be filled in by hand as in other Masechtos which have missing drawings. Here is an example of such a situation in the Bomberg Eiruvin.

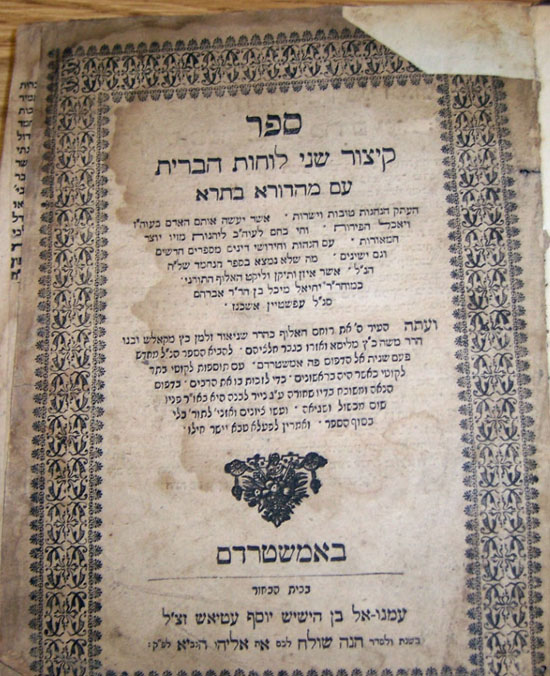

Moving forward I did not find these diagrams from Yoma 11b in the Constantinople 1585 edition, the Frankfurt on Oder 1698 edition ( even though it has the diagrams from Eiruvin ), or the Amsterdam 1740 edition. I did find fairly accurate diagrams in an Amsterdam 1714 edition but I believe they were drawn in.

The first edition I found these printed diagrams in was Amsterdam 1743 from the Proops printers. Here is what it looks like.

I did not find this diagram ( maybe it is two diagrams?) very helpful in understanding what Rashi meant when he said “Kazeh”. The diagram seems almost humorous to us, but imagine how many eyes studied this diagram and tried to make sense of it.

As mentioned before, by 1831, there were very helpful diagrams in editions printed in Prague, Vienna and Lemberg. The same cannot be said of the Zhitomir edition of 1864 which looks like this.

The first diagram is not nearly as accurate as the one in the previously mentioned editions. It mainly tries to show that the structure of the gate parallels the doorway by “curving” inwards. The second diagram which resembles a tooth, shows the doorway narrowing as it extends upwards with the gate structure maintaining its rectangular shape. My opinion is if a Rashi says Kazeh, the diagram should be as helpful as possible. No one expects a sophisticated illustration but it should be something that clearly shows what Rashi meant. In this case, I think the diagram should look like a doorway within a gate or walled structure.

We finally get to the Vilna Shas. The editors of this Shas clearly had the Vienna, Prague and Lemberg editions at their disposal. They knew what these diagrams could look like. Yet their diagrams look very much like the Zhitomir edition, with a little improvement on the second diagram.

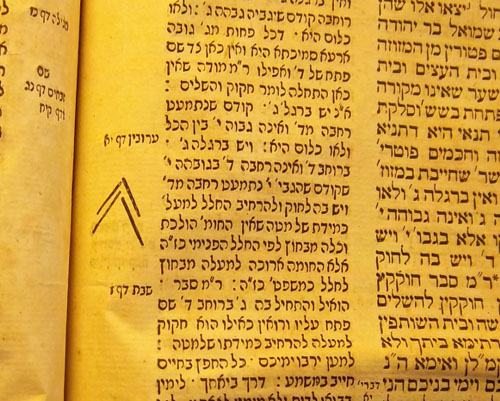

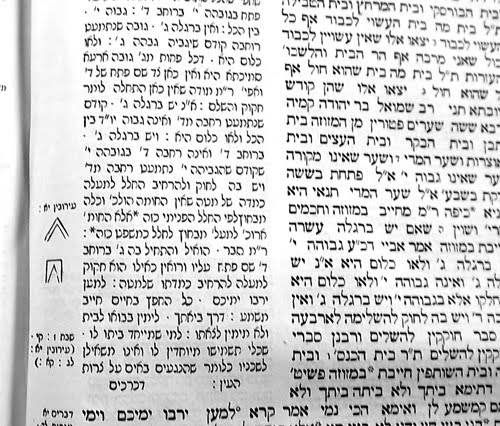

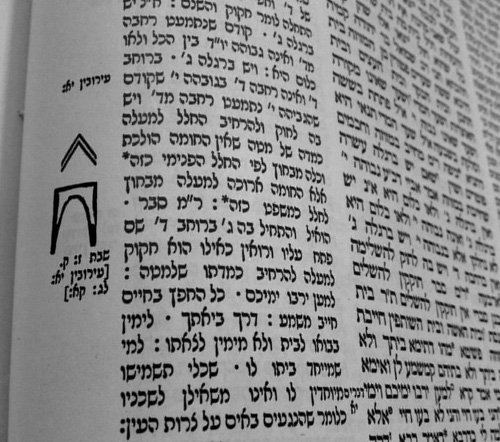

It is possible they did not have the technology to replicate the Prague 1831 edition but that seems unlikely, because in a parallel Sugya in Eiruvin 11b they have diagrams that look like this.

Maybe they had a Rashi manuscript that made the first diagram look like this ^. But even so, I think they should have tried to make things as clear as possible and the two diagrams they chose just do not do that.

Perhaps the ultimate irony in this whole Sugya is that not only may the diagrams be incorrect, but even the term “Shaar Madai” may be incorrect. The Rashash notes that in K’sav Ashuris, a Mem and a Tes look similar, and because of a Ta’us Soferim, the term Madai was used instead of the correct “Shaar Taddi”, which was a gate on the Har Habayis.

(This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library)

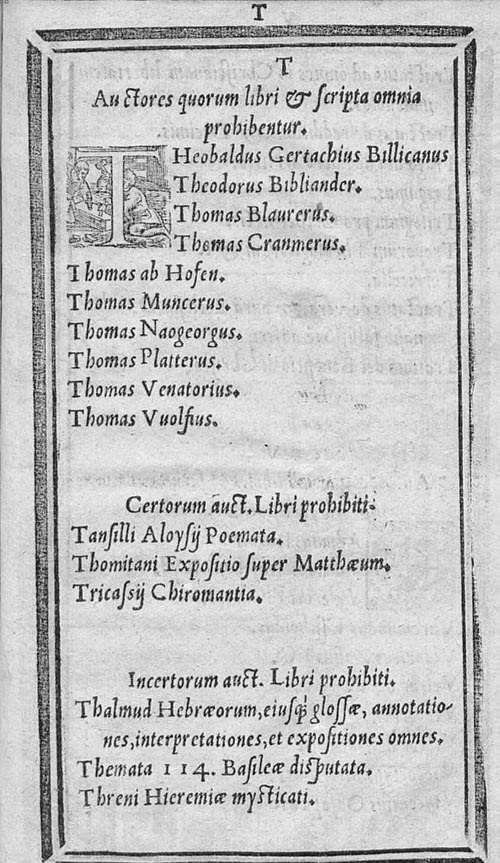

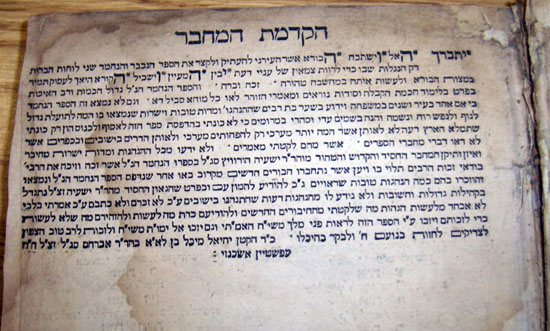

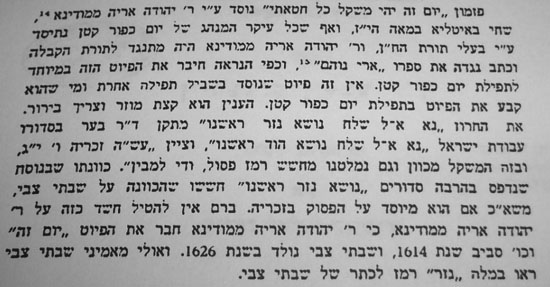

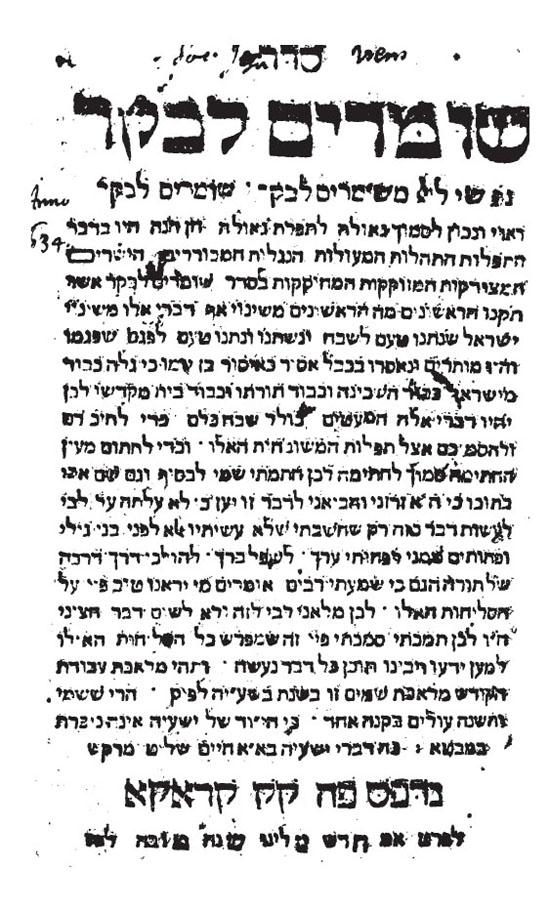

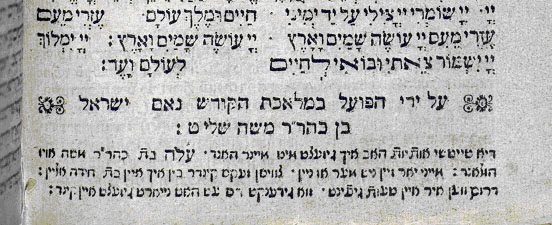

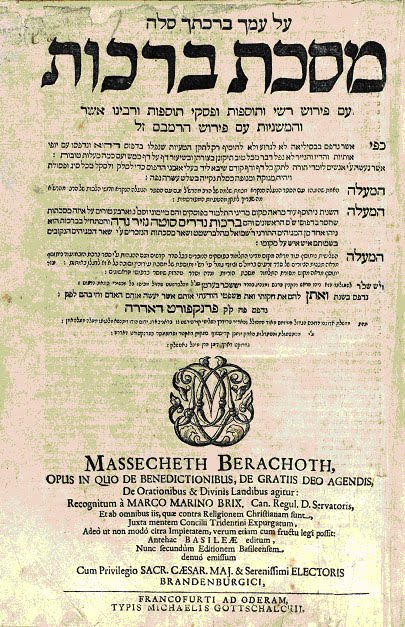

(This scan and those following are all courtesy of the JTS Library) The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague:

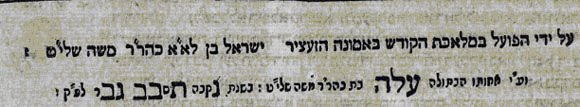

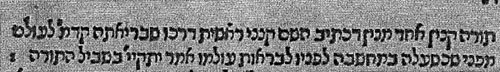

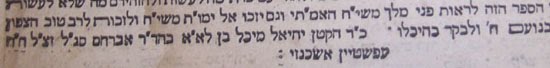

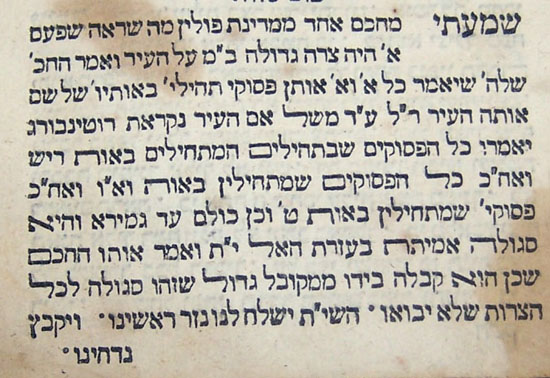

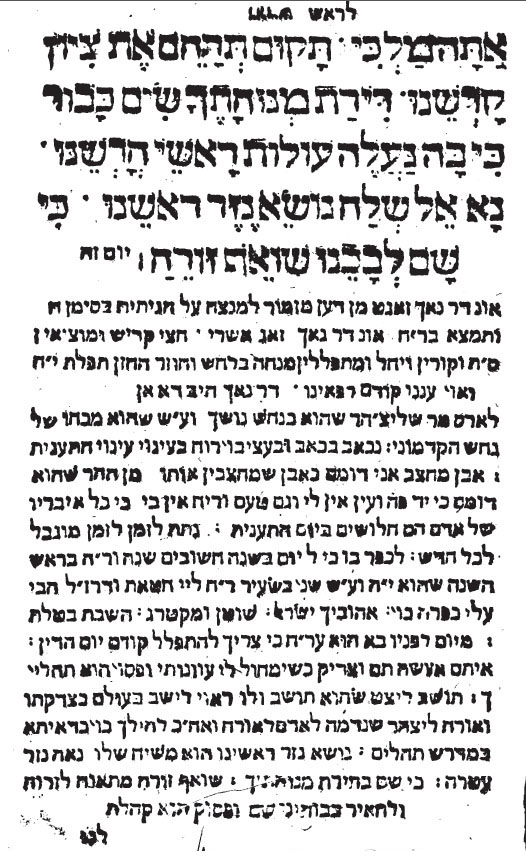

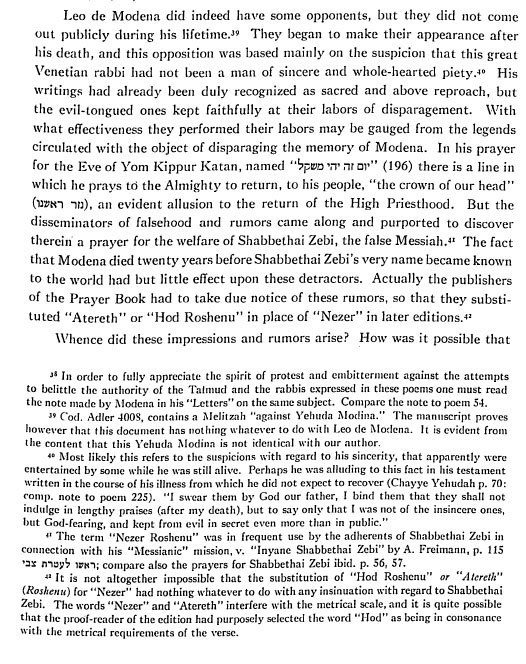

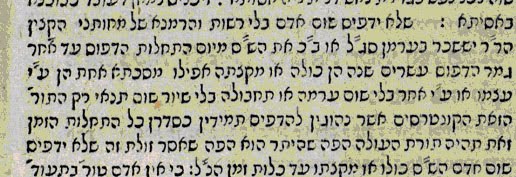

The Berman Shas is one of the most respected early printed editions of the Talmud because it contained many additional commentaries which became standard in following editions. It was the first edition since that of Gershom Soncino in the early 16th century to contain most of the diagrams we are familiar in Seder Zeraim, and Masechtos Eiruvin and Sukah. (5) It was also the first to contain Charamos from various Rabbanim prohibiting others in that general area from printing the Talmud for an extended period of time.(6) The following Cherem, recorded in Maseches Brachos, was written by Rav Dovid Oppenheim who lived at that time in Nikolsburg and later became chief Rabbi of Prague: At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.

At the end of Maseches Nidah printed in 1699, Elle signs her work a bit more boldly, and leaves us wondering what was going through her mind when she set the letters for the colophon.