What’s Wrong With Wealth and Honor?

by Eli Genauer

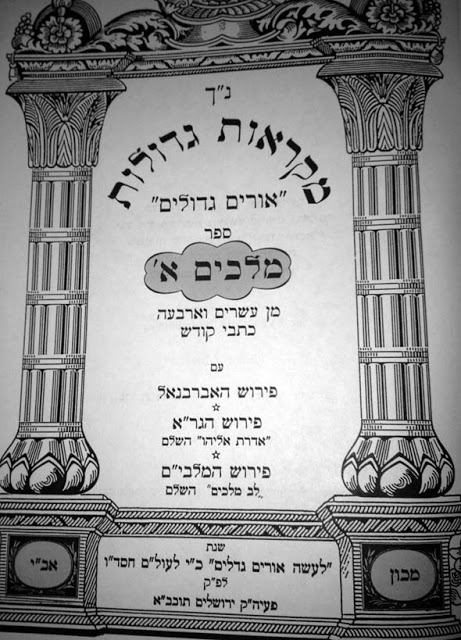

Below, we will present some timely notes regarding an English/Hebrew Machzor for Rosh Hashana which was printed in England in 1807. We will touch upon a variety of issues, and thus first present general backgrounds regarding Hebrew printing in London, the prayer for the state, and Kol Nidrei.

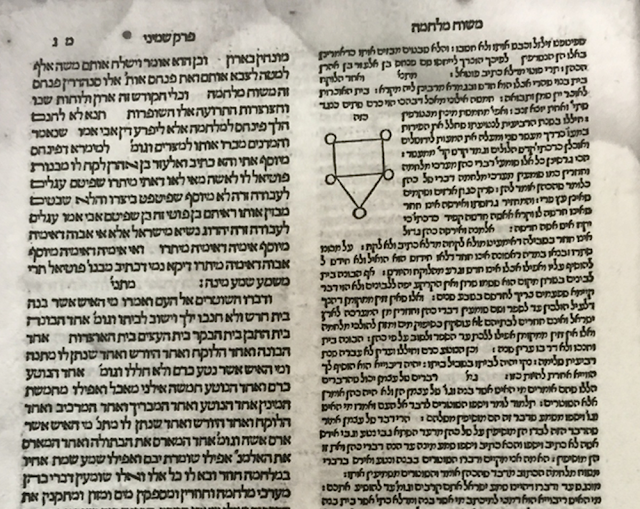

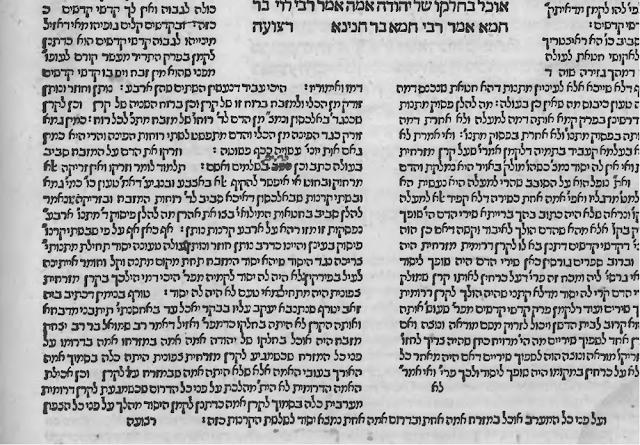

Hebrew Typography in London

The earliest use of Hebrew typography in England is sometime in the middle to the late 1520s. Of course, at that time, Jews were banned from England and the earliest works containing Hebrew type in England were produced for non-Jews.

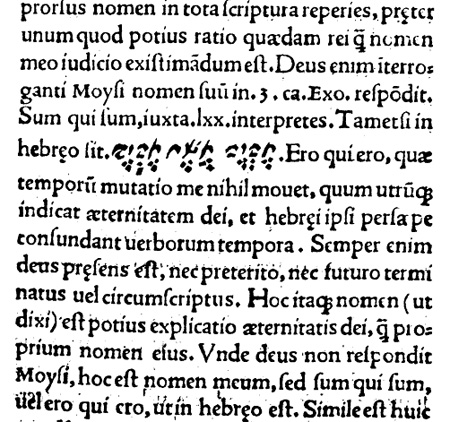

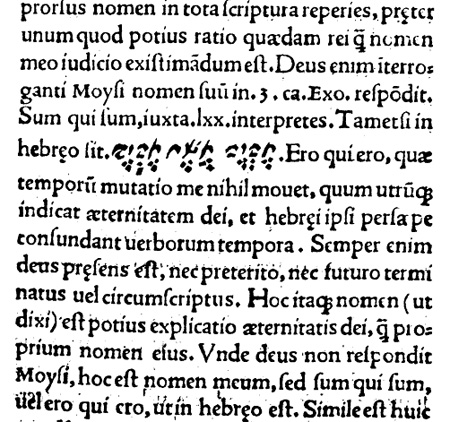

The prize of first was thought to go to Thomas Wakefield’s publication of his address regarding “Three Languages” – Hebrew, Arabic and Chaldean (

Oratio de laudibus et utilitate trium linguarum [

link]). The type, as you can see, was quite primitive.

This lecture was given in 1524, and as the book itself is undated, it was assumed that the lecture was published soon after it was given. Thus, many dated it to 1524/25. Wakefield, a noted Hebraist, actually spends the majority of the book discussing Hebrew and the other two languages get short shrift.[1]

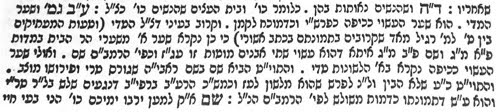

Recently, however, the dating of this work has been challenged and been shown to likely incorrect. The author, in the self-described “Holmesian manner,”[2] highlights the various persons Wakefield claims to have tutored in Hebrew and the honorifics used to describe those persons.[3] Based upon some of the descriptions, it seems likely that Wakefield’s work was not published prior to 1527 and most likely in 1528. [4] This conclusion, coupled with the dating of another work by a different author, unseats Wakefield’s book claim to first. Instead, Richard Pace’s Praefatio in Ecclesisten, printed in August 1527, is the most likely candidate for the first use of Hebrew typography in England.[5] Here is a sample:

It took nearly two hundred years after the appearance of Hebrew typography for the first Hebrew book published for a Jewish audience in England. The controversy surrounding R. David Nieto’s remarks and their affinity or lack thereof to Spinoza would produce the first printed Jewish Hebrew book in England. The first was a very small one, only a few pages, of a responsum written by R. Tzvi Ashkenzi, in R. Nieto’s defense, and published in 1705. It included both Spanish as well as Hebrew (available

here).[6] For more on R. Nieto and this controversy, see the Seforim Blog’s earlier post

here.

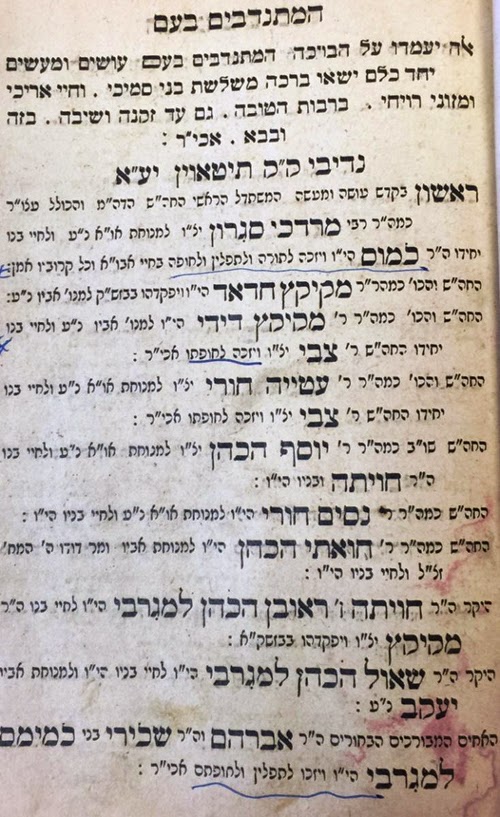

The Prayer for the Welfare of the State

The prayer for the welfare of the king or ruler is ancient. Many point to the statements of Ezra as well as the passage in Avot as early sources for the prayer. A variety of rationales are offered for this obligation. For example, Rabbenu Yonah interprets the need for these prayers as indicative of a Universalist worldview, which requires all humans to display empathy for one another. In order to effectuate that goal, Jews therefore pray for not only the Jewish leaders but also the secular one. R. Azariah di Rossi, claims that the prayer carries a pacifist message as he emphasizes the lack of allegiance to a specific ruler or country and thereby transforms the prayer into one arguing for peace among all nations.

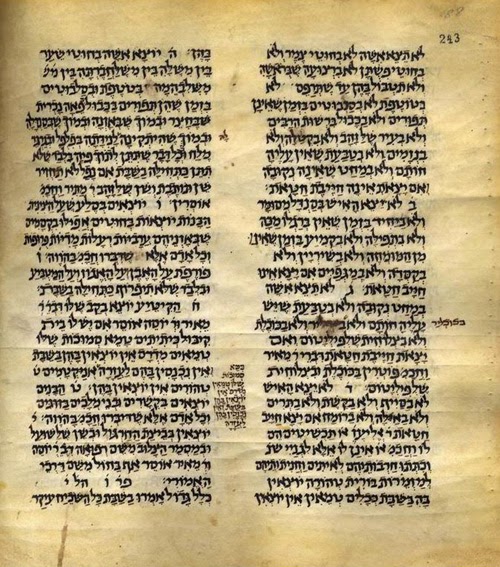

The earliest extant prayers are from the Geniza, and can be dated to between 1127 and 1131. The prayer is for the “Fatimid caliph al-Amir bi-ahkam Allah who ruled Egypt and its regions during the years 1101-1131.” See S.D. Goitein, “Prayers from the Geniza for Fatimid Caliphs, the Head of the Jerusalem Yeshiva, the Jewish Community and the Local Congregation,” in Sheldon R. Brunswick, ed., Studies in Judaica, Karaitica and Islamica: Presented to Leon Nemoy on His Eightieth Birthday (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1982), 47-57.[7] In this instance, the prayer includes not only a prayer for the secular ruler, but also a prayer for the local Rosh HaYeshiva. Additionally, it blesses all of the Rosh HaYeshiva’s deceased predecessors, providing a nice genealogy. Goiten posits that these prayers may have been written in response to specific historical events and may not be indicative of the general practice in 12th century Egypt. See id. at ___.

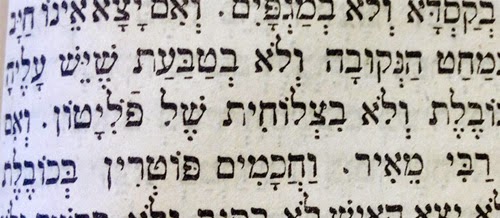

The earliest sources, however, do not include the modern formulation of HaNoten Teshua. Instead, early on there was a lack of conformity regarding this prayer. Kol Bo records the custom but indicates that each community had its own practices. But, none used the HaNoten Teshua formulation. The first extant example of HaNoten Teshua is found in a Spanish manuscript dated between 1479-92.[8] Ironically, this example was prepared for King Ferdiand V, who, in 1492, issued the expulsion order.

It appears that with the expulsion and dispersion of the Spainish Jews, the HaNoten Teshua was disseminated throughout the Jewish world. Indeed, the inclusion of this prayer in Yemenite rites, appears to undermine a major thesis of the noted Yemenite scholar, R. Yosef Kapach. He asserts that the rite presents a pristine rite, unchanged over hundreds of years. But, as the Yememite rite includes HaNoten Teshua, which is from the 15th century, indicates that the Yemenite rite is less pristine than Kapach would have it. [9]

The prayer is also linked to the readmission of Jews into England. Menasseh ben Israel in his plea for readmission of the Jews to England (

link) provides the

full text – in English – of the

HaNoten to demonstrate the Jews’ loyalty to their rulers.[10]

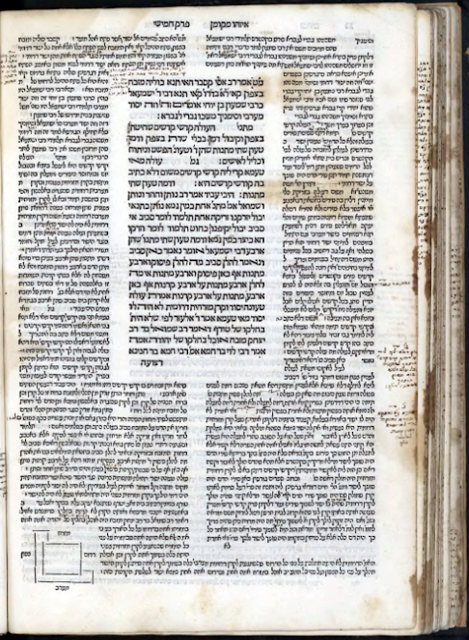

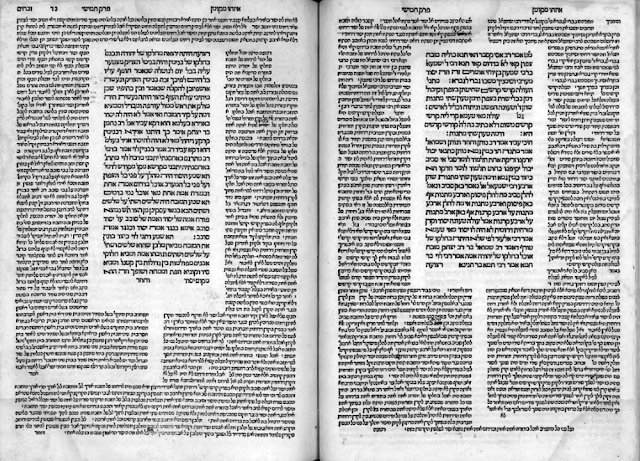

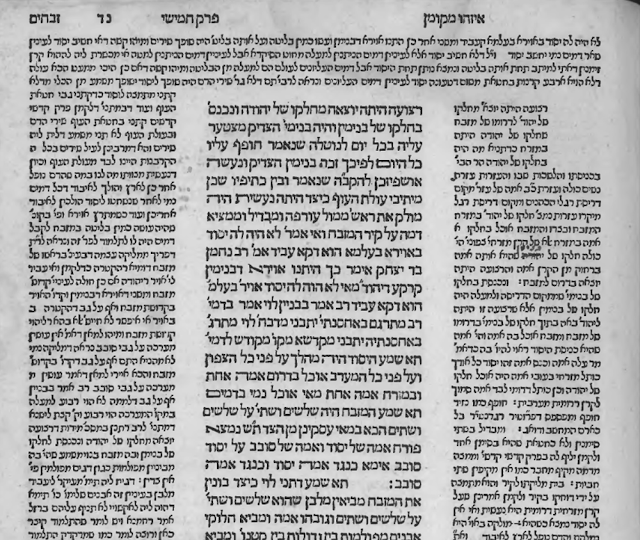

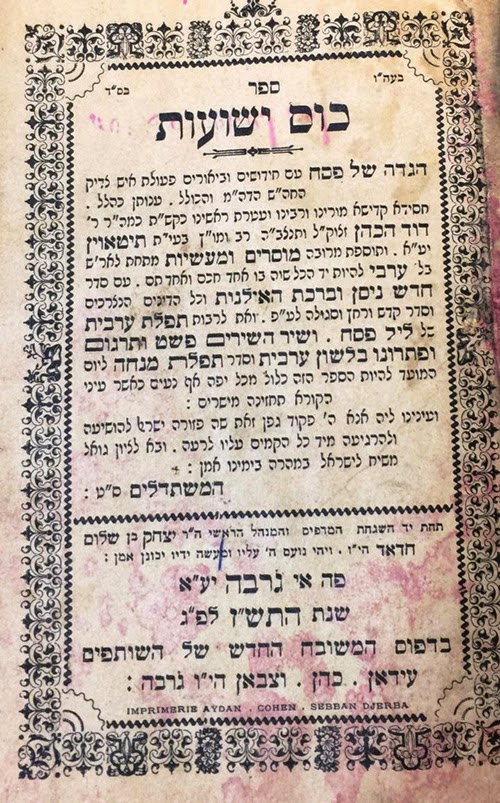

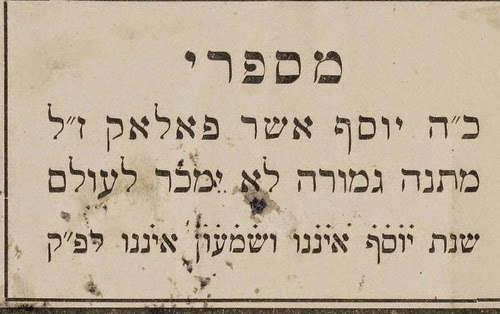

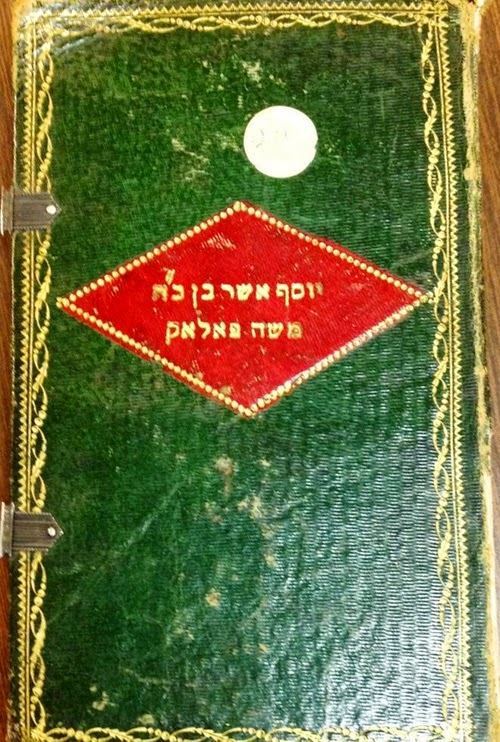

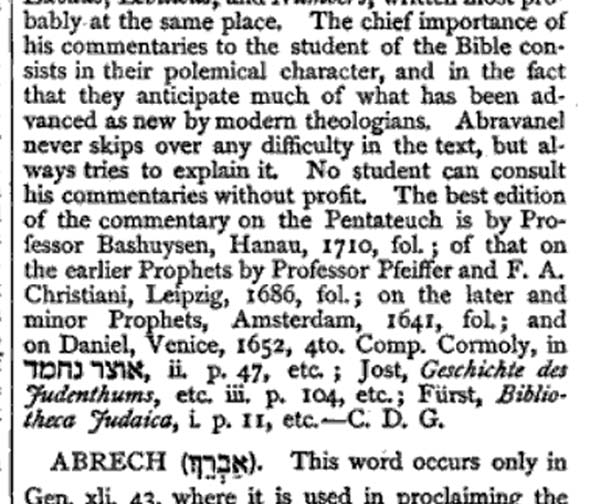

A English Hebrew Machzor Printed in London

The Jewish Encyclopedia notes “In 1794 David Levi published an English version of the services for New-Year, the Day of Atonement, and the feasts of Tabernacles and Pentecost, and thirteen years later gave a new version of the whole Mahzor. This second edition was “revised and corrected” by Isaac Levi, described as a “teacher of the Hebrew Language.”

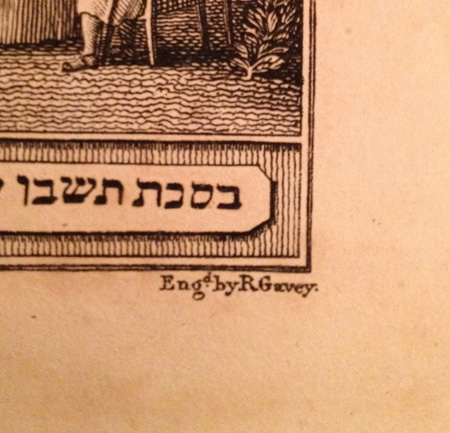

The Machzor features a frontispiece with various engravings of the Jewish holidays. The engraving for Shavuos features Moshe Rabbeinu dressed in a manner probably unknown 3,000 years ago, and holding the Aseres HaDibros with the numerical sequence from left to right. Yom Kippur correctly shows two identically sized “Se’irim” as per our tradition.

If you look closely at the name of the engraver, you will see that it was done by an R. Gavey.

I tried to find out more about R. Gavey and finally came upon a website which dealt with his family. I sent an email to the address listed and waited and waited. Two years later, I received the following response from a fellow in Australia:

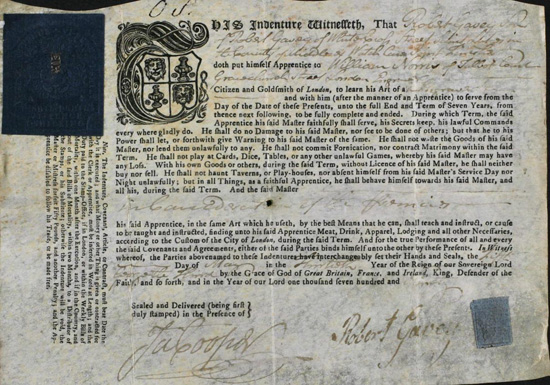

“Robert Gavey b.1775 London was my 4xGreat Grandfather. He is listed as an engraver. Both his father and grandfather were watch makers. Robert Gavey’s daughter Harriot Angelina Gavey married my 3x Great Grandfather whose son James Fletcher emigrated to Australia 1852. The Fletchers were originally Huguenot silkweavers with the surname Fruchard and I believe the Gavey’s would have been Huguenots also.”

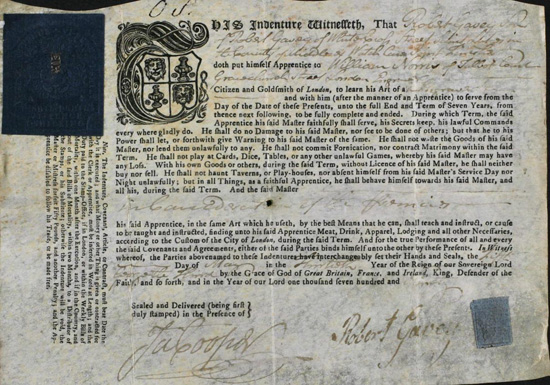

It turns out that Robert Gavey’s Australian descendent had a copy of his certificate of indenture as an engraver to a goldsmith named William Norris. Robert was 15 years old at the time (1790) and his period of indenture lasted for seven years. He promised not get married during that time period or play cards or dice. He also was forbidden to frequent taverns or playhouses or engage in any act which would cause his master a loss of money. (Click to see a large, high-resolution image.)

The certificate of indenture was signed in May of 1790 which was noted as the thirtieth year of the reign of George III who is described as the king of Great Britain, France, and Ireland.

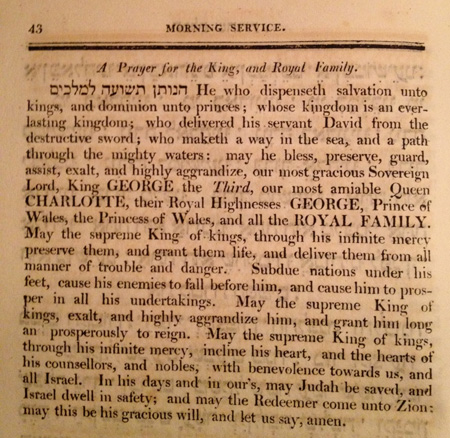

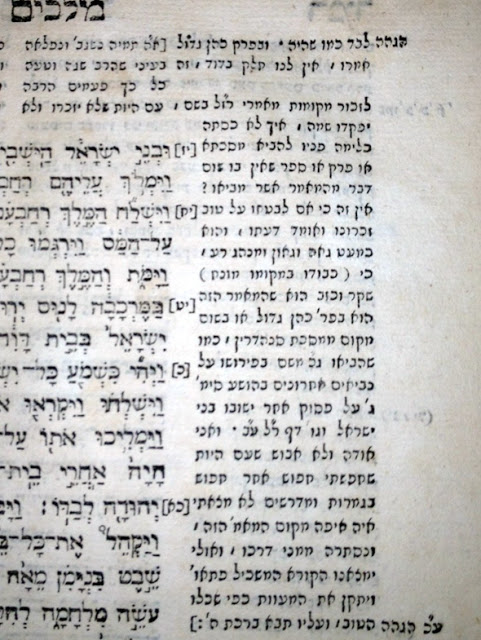

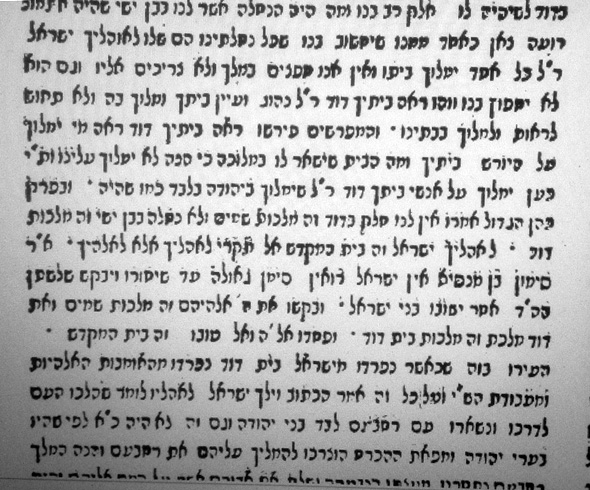

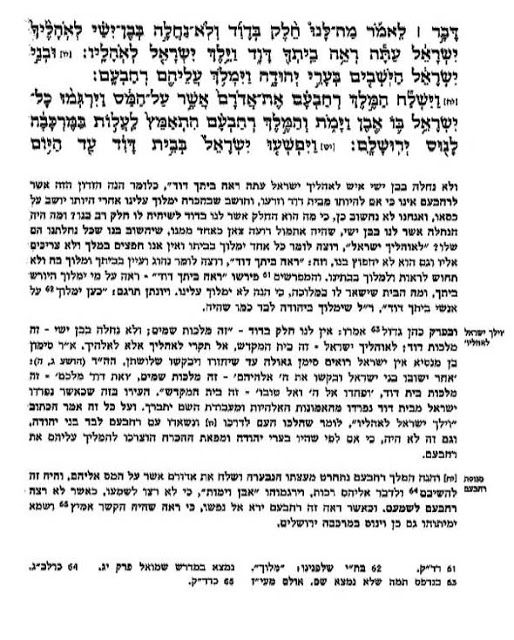

Speaking of George III, he received much better treatment in this Machzor than in our American Declaration of Independence. On our side of the pond, we know George III as a man who “ has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.” As part of the agreement by Cromwell to allow Jews back into England, the Jews promised to always pray for the welfare of the ruler. Accordingly, this Machzor blesses King George in this manner:

This is not the only edition that continued to praise the monarch. Isaac Lesser, published the first complete machzor in the United States in 1837-38, for the Spanish and Portuguese rites with an English translation. Lesser’s translation relies heavily upon that of David Levi’s translation.[11] In an attempt to sell his machzor in both the United States as well in other English-speaking locals, he includes two version of the prayer, one asked that God “bless, preserve, guard, assist, exalt, and raise unto a high eminence, our lord the king.” The other, replaced this phrase with the request that God “bless, preserve, guard, and assist the constituted officers of the government.”[12]

The person who finally brought the prayer for the government more in keeping with American democratic values was Max Lilienthal (1814-1882).[13] While some had been willing to change the prayer, they did so only in the vernacular but retained the Hebrew

HaNoten Teshua. Lilienthal, however, totally reworked the prayer, altering its tone and focus. Lilienthal removes all mention of kings, focuses on the country more than its rulers, and seeks to bestow God’s blessing, not on the ruler but on all the inhabitants of the land. This version was included in Henry Franks’s

Teffilot Yisrael, a siddur containing the Orthodox liturgy. This siddur was first published in 1848, and reissued in more than 30 editions. As Sarna

notes, the acceptance of the prayer is somewhat ironic in that Lilienthal, later became part of the American Reform movement, was the author of a prayer that became the standard even in Orthodox siddurim.[14] Id. at 436.

Aside from changing the text of the prayer to fit American sensibilities, how the prayer was recited was also changed. Congregation Shearith Israel, in New York, after the revolutionary war, “ceased to rise for Hanoten Teshu’ah. According to an oral tradition preserved by H.P. Solomon, ‘the custom of sitting during this prayer was introduced to symbolize the American Revolution’s abolition of subservience.’”[15]

The United States was not the only country to undergo significant changes to its governmental structure. France, in 1787, abolished (temporarily) the monarchy. After which the prayer for the welfare of the government was radically changed. Instead of praying for the benefit of kings and rulers, the French prayer focuses upon the Republic and its people. All the biblical verses included bless the people and not the king. [16] The prayer begins “Look down from your holy place on our land, the French Republic, and bless our nation, the French people, Amen.”

Other changes to the prayer, due to time and place, were common. For example, during the height of the Sabbati Zevi messianic frenzy, two versions of the prayer were produced, not asking to bless the secular ruler, but, instead, blessed Shabbati Zevi.

Today, the most significant change to this prayer has been the new prayer on behalf of the State of Israel. The authorship of the prayer as well as its use is subject to controversy.[17]

In the most recent “Prayer For the State” news, French President François Hollande, specifically invoked this prayer when discussing French Jews’ relationship to the state. He included in his remarks, translated in NYRB, commemorating the round-up of Jews at the Vélodrome d’Hiver: “Every Saturday morning, in every French synagogue, at the end of the service, the prayer of France’s Jews rings out, the prayer they utter for the homeland they love and want to serve. ‘May France live in happiness and prosperity. May unity and harmony make her strong and great. May she enjoy lasting peace and preserve her spirit of nobility among the nations.'”

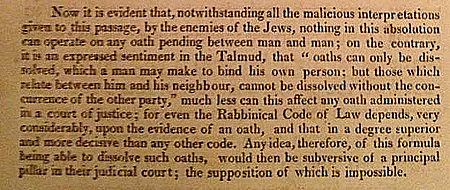

The Yom Kippur volume of this set contains a detailed “apology”for the Kol Nidre prayer. The Jews endeavored to incorporate themselves into general society and felt the need to emphasize that their word was binding on them. Kol Nidre was seen as indicating otherwise, so an explanation of the prayer was seen as necessary, both for Jew and Gentile. (See Y. Goldhaver,

Minhagei Kehilot, Jerusalem: 2005, pp. 209-19 on the history of Kol Nidre and the controversy.) It concludes as follows.

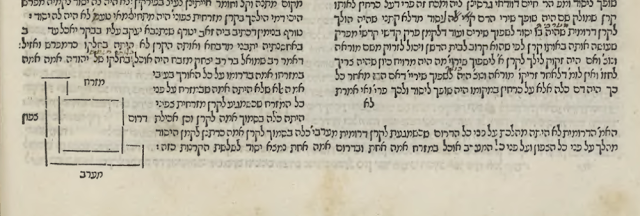

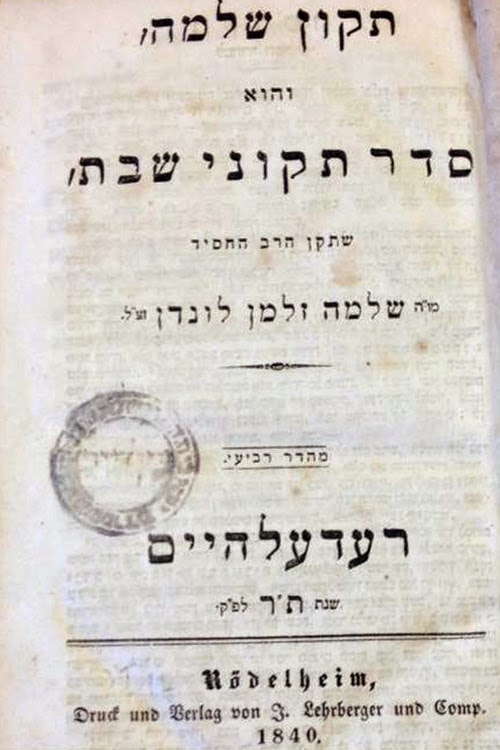

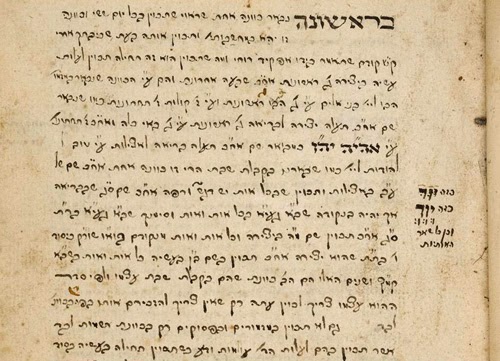

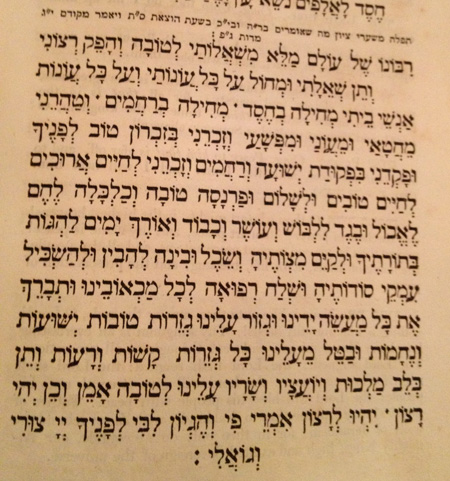

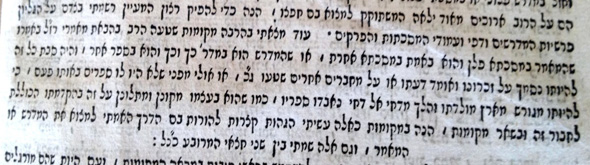

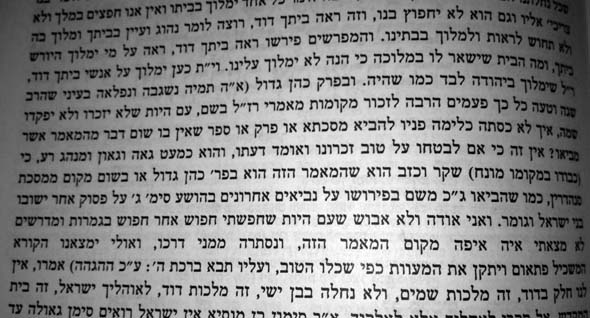

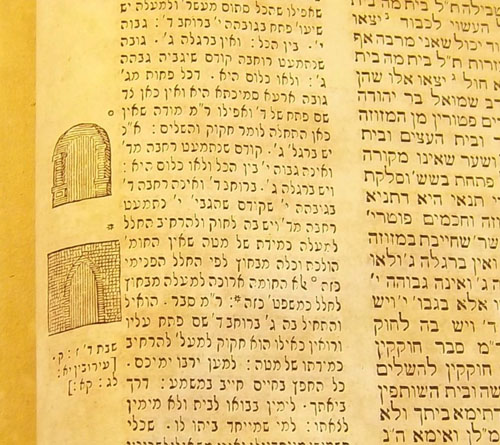

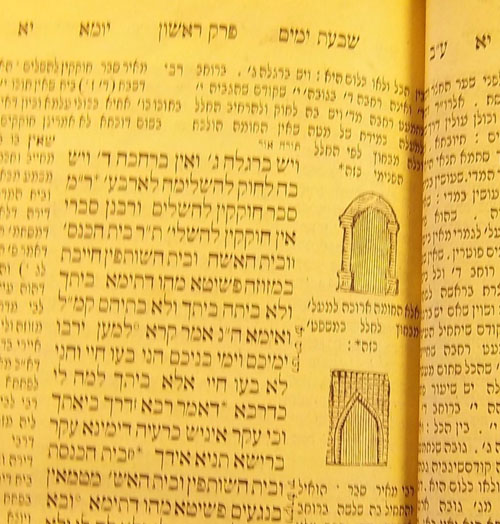

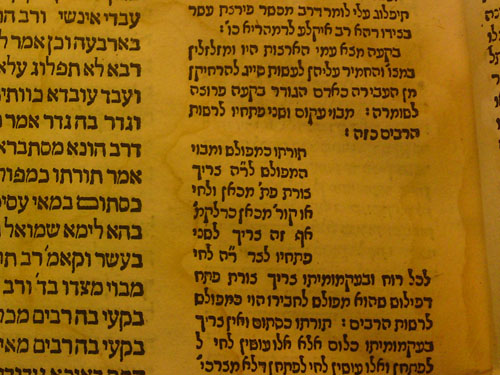

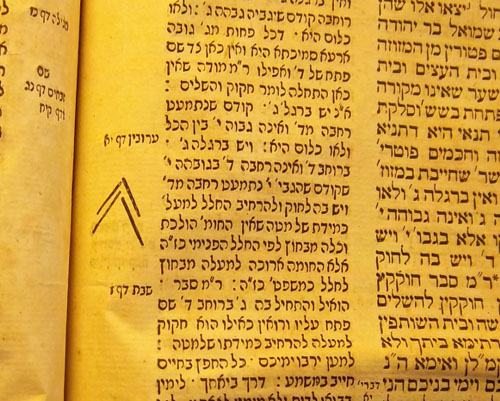

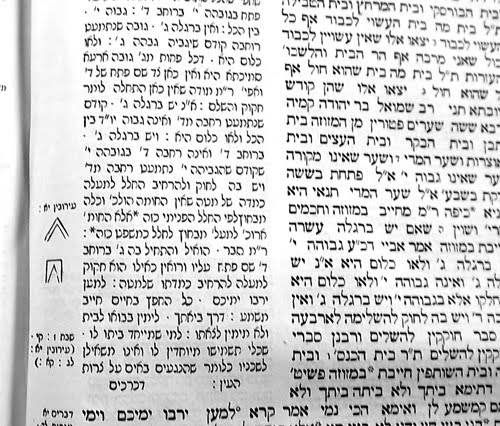

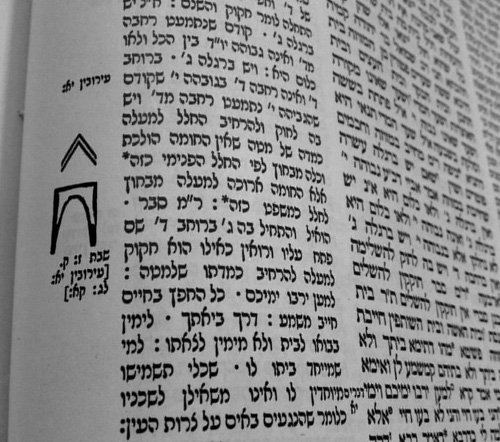

Finally, I would like to focus on the special prayer said during the Yamim Noraim when the Torah is taken from the Aron Kodesh. It first appeared in the

Siddur Shaarey Tzion of Rabbi Nathan Hanover and begins with the words “Ribbono Shel Olam”.

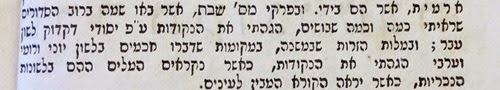

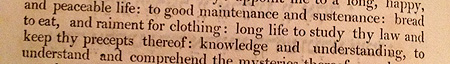

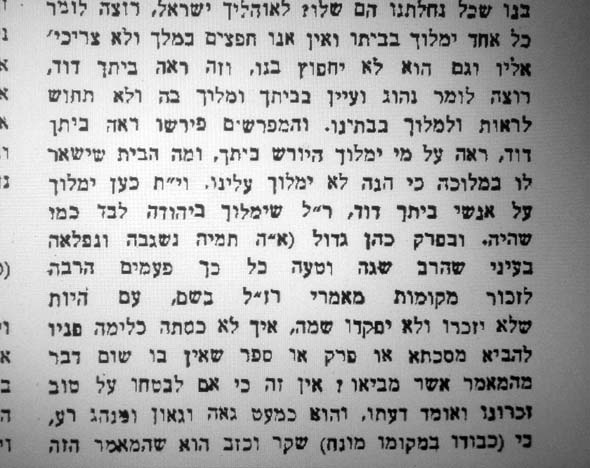

In it we ask Hashem to remember us for a long and good life, with everything that comes along with that. We include in our request that Hashem should provide us with “Lechem Le’echol, Beged Lil’Bosh, V’Osher V’Chavod”. Let us see how David Levy translates these words.

As you can see, the request for “wealth and honor” is nowhere to be found in the English translation. I was curious about this and asked Dan Rabinowitz for his opinion. He offered that it is possible that this Machzor was printed at a time when the English community was quite interested in the Hebrew language. Non-Jewish scholars eagerly bought any books printed in Hebrew. As such, it could be that Levy decided to leave out the reference for our desire for wealth and honor because, well, maybe it was a bit too pushy on our part.

I hope all of you are blessed with a Shana Tova, even one that includes within it the promise of wealth and honor.

[1] See Marvin J. Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book, Brill, Leiden:2004, entry for Oratio and pp. 959-60 and the sources cited therein. But see Brad Sabin Hill, Incunabula, Hebraica & Judaica . . .” Ottawa:1981, #52 asserting that 1561 is the earliest introduction of Hebrew typography to England. It is unclear what the basis of that assertion is.

[2] Richard Rex, “Review: Robert Wakefield On Three Languages 1524,” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42:1 (Jan. 1991) 159.

[3] Richard Rex, “The Earliest Use of Hebrew in Books Printed in England: Dating Some Works of Richard Pace & Robert Wakefield,” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, Vol. 9, No. 5 (1990), 517-25.

[4] Id. at 517-18.

[5] Id. at

[6] See B. Roth, The Hebrew Printing Press in London, Kiryat Sefer 14 (1937), pp. 97-99.

[7] See also, Fenton,

[8] See Aaron Ahrend, “Prayers for the Welfare of the Monarchy and State,” in Aaron Ahrend, ed., Israel’s Independence Day: Research Studies (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1998), 176-200 (Hebrew). This date is contrary to Schwartz who incorrectly posits that there is no evidence of HaNoten Teshua prior to the 16th century, and none in pre-expulsion Spain. See Barry Schwartz, “Hanoten Teshua: The Origin of the Traditional Jewish Prayer for the Government,” in HUCA, 57, (1986) 113-20. Sarna appears unaware of Ahrend’s article as he continues to assert that HaNoten Teshua was not composed prior to the 16th century. See Jonathan Sarna, “Jewish Prayers for the United States Government: A Study in the Liturgy of Politics and the Politics of Liturgy,” in Ruth Langer & Steven Fine, eds., Liturgy in the Life of the Synagogue: Studies in the History of Jewish Prayer (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2005), 207 & n.9 (link).

[9] See Ahrend, “Prayers for the Welfare,” at 183.

[10] See Menasseh ben Israel, The Humble Address to his Highness the Lord Protector, 1655.

[11] Leeser was not the first American to utilize Levi’s translation. The first Hebrew prayer book published in the United States, The Form of Daily Prayers (Seder Tefilot), New York, 1826, also includes an English translation by Solomon Henry Jackson. Jackson, who emigrated to the United States from London, also relied heavily upon Levi’s translation. Jackson, in the introduction, indicates that HaNoten Teshua was adapted for U.S. audience, in fact, the Hebrew remained the same, only the “translation” was altered. See Sarna, Jewish Prayers, 213.

Additionally, some time in the 1820s, there was an attempt to reprint Levi’s machzor in the United States. A prospectus was issued, but Levi’s machzor was never reprinted in the United States. See Yosef Goldman, Hebrew Printing in America 1735-1926, Brooklyn, NY, 2006, no. 33.

The first appearance of HaNoten Teshua in the United States is found in the first prayer book published in the United States. Isaac Pinto’s holds that honor. In his English only edition whose first volume was published in 1761 with the second volume published in 1766, he includes HaNoten Teshu’ah.

[12] Jonathan Sarna, “Jewish Prayers for the United States Government,” at 215.

[13] See Jonathan Sarna, “A Forgotten 19th-Century Prayer for the United States Government ,” in Hesed ve-Emet, Studies in Honor of Ernest S. Frerichs, ed. Magness & Gitin, Atlanta, Georgia, 1998, 431-40.

[14] Today, however, the most widely used Orthodox siddur in the United States, Artscroll, does not include the prayer in any form in its standard editions. It is unclear why Artscroll omitted this very old prayer.

[15] Sarna, Jewish Prayers, at 210.

[16] Moshe Katon, “An Example of the Revolution in the Hebrew Songs of the French Jews,” Mahut 19 (1997) 37-44, esp. 37-8.

[17] See Aharon Arend, “The Prayer for the Welfare of the Monarchy and Country, in Arend ed., Pirkei Mehkar le-Yom ha-Atzmot, Ramat Gan: 1998, 192-200.