An “Artscroll”™ Illustration in the Vilna Shas-Masechet Shabbat 98b

An “Artscroll” ™ Illustration in the Vilna Shas–Masechet Shabbat 98b

By Eli Genauer

לזכר נשמת אבי מורי ר׳ יעקב קאפל בר׳ משה יהודה הלוי גענויער ז״ל. היארצייט שלו י״ד סיון.

For those studying Daf Yomi this week, there is a unique diagram that appears on Shabbat 98b. In the Vilna Shas one can see a closeup “picture” of one of the boards of the Mishkan (“קרש“) which would make Artscroll proud.[1] While one might be familiar with diagrams that appear in the Talmud, those diagrams illustrate comments in the rishonim, mainly Rashi. Most of these are called out specifically by Rashi: “kazeh” “like this.” Artscroll, however, includes their own illustrations beyond those from any of the rishonim. Yet, they were not the first publishers of the Talmud to do so. Indeed, this diagram on page 98b is a much earlier example of a publisher electing to incorporate their own diagrams into the text.

Diagrams in Printed Editions of the Talmud

The use of diagrams is attested to in numerous manuscripts. These diagrams appear in Rashi, Tosefot and even were used by the Geonim.

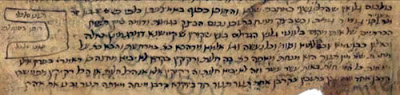

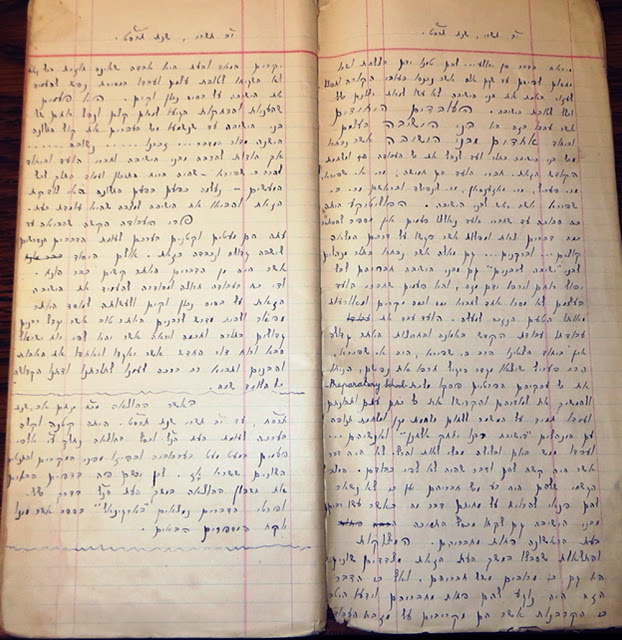

When manuscripts gave way to printing in the late 1400’s and early 1500’s, those diagrams were excluded in the early printed editions of the Shas. When Daniel Bomberg published the first complete edition of the Shas in the early 1500s, he did not include the actual diagrams, but instead left a space for the book’s owner to pencil in the relevant diagrams (how they would know what the diagram looked like is left unanswered).

Finally starting with 1697, (the Berman Shas of Frankfurt on der Oder) did diagrams start to reappear in the empty spaces (mostly in Eruvin and Sukkah).

What was the source of those diagrams in the Berman Shas and in ones that were printed soon after in the early 1700’s? There were three sources, the Maharshal, Maharsha, and Mahram of Lublin.

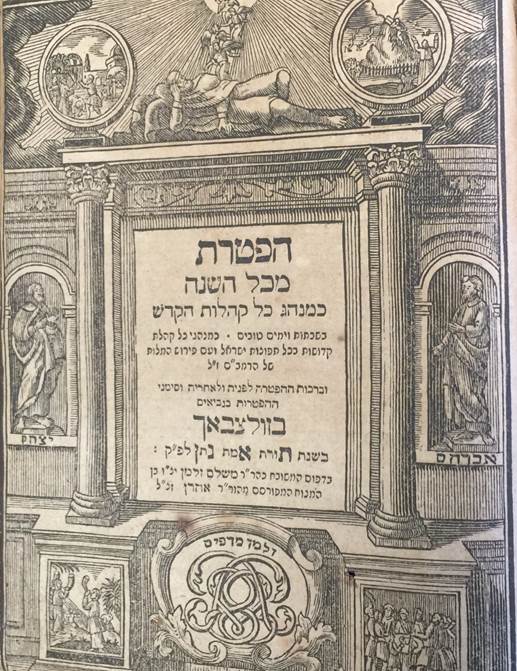

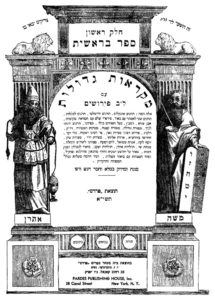

This is the Shaar Blatt from the Frankfurt on der Oder 1697 edition:

The Maharshal is the key point person when it comes to diagrams. He had the 2nd edition of the Bomberg Shas (printed circa 1528) and made his notations there. He recognized the importance of the Shas being printed but also the dangers that lay in the fact that if there was a mistake, it would find its way into thousands of hands. He lived at a time when there were still manuscripts around, and he made his corrections based on those manuscripts and also his own logic. Since he had the status of an Adam Gadol, his own logic carried much weight. Originally, he did not set out to write a book with his corrections. Like the Ba’ch, he just made the corrections in his own Gemara. After he died though, his sons printed Sefarim which reflected his notes.[2] Therefore, if in the late 1600’s or early 1700’s you were printing a Shas, and you looked at a previous edition and in Rashi it said “Kazeh” and there was a space, you would look at the Chochmas Shlomo. If he had added a diagram, you would place that diagram in the empty space and feel comfortable that it had good Yichus. There were times that there wasn’t an empty space that the Chochmas Shlomo shows a diagram, and in that case, the printers usually added it.

The 1715 Amsterdam Edition of the Talmud

A complete edition of the Talmud was first published in Amsterdam in the 1640s by Immanuel Benveniste. In the 17th and 18th centuries Amsterdam was counted among the most important cities for the printing of Hebrew books and there were many well-known publishers that followed Benveniste and they printed many important works yet none of them attempted to reprinting the Talmud. Only some sixty years later did Amsterdam see a Talmud come off its presses. This one, that began in 1714, was never completed.

R. Judah Aryeh Loeb ben Joseph Samuel of Cracow appealed to Samuel ben Solomon Marsheses and Raphael ben Joshua de Palasios prominent members of the Amsterdam Sephardic community and asked them to print a new edition of the Talmud. Neither had ever published a book. In 1710, Loeb unsuccessfully sought to publish an edition of the Talmud in Frankurt. Now, in Amsterdam he sought to try again. Marcheses and Palasios formed a printing house specifically to print a “fine and accurate edition,” in an environment that “the workers would not be hurried so that they could work with care, reducing errors, and under the supervision of … the dayyan of the Ashkenaz Rabbinic Court of Amsterdam who would help establish the correct text.”[3] An emissary was sent to visit various Jewish communities to collect subscribers and reduce the burden of the significant printing costs. Relevant to diagrams, the emissary came bearing a gift, the Amsterdam 1710 edition of R. Jacob ben Samuel Bunim Koppelman of Brisk’s (1555-94) Omek Halakahah (first printed in 1510), a book that includes many diagrams to explain difficult passages of the Talmud.[4]

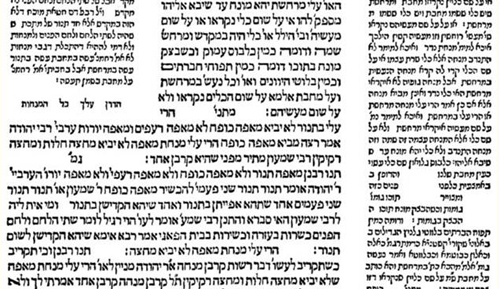

The first volume, Berakhot, was published in 1714[5] and the editors note the sources for their text and likely for the diagrams as well.

-

Chochmas Shlomo

-

Chochmas Manoach

-

Chidushei Halachos of the Maharsha

-

Maharam Lublin

-

Sifrei Hashas of Yosef Shmuel ben Zvi – seemingly these were concentrated on Zeraim, Kodshim and Taharos

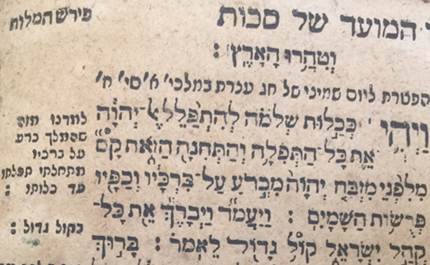

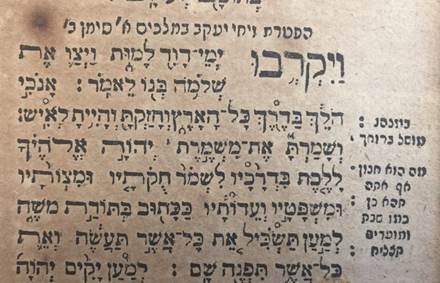

The volume on Meseches Shabbos was published in 1715 and the top 4 appear in the Hakdamah:

The Source and Purpose of the Diagram in Shabbos 98b

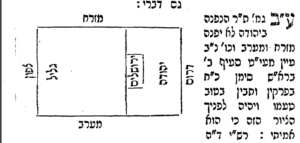

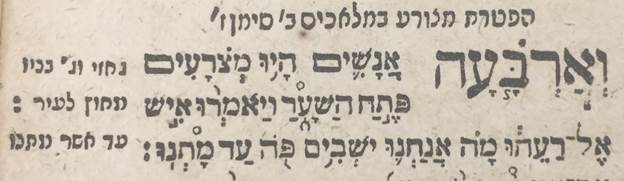

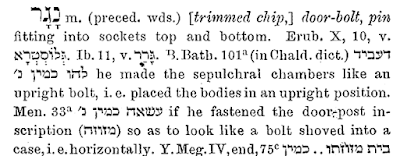

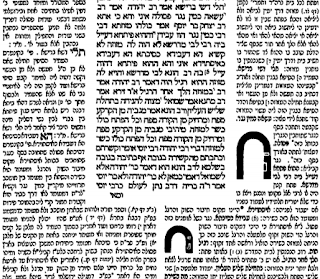

The Gemara in Masechet Shabbat on Daf 98a and b deals with the laws of carrying and discussing some of the details of the boards (“קרשים“) which made up the walls of the Mishkan.[6] These board were comprised of a complex system designed to keep each board straight and provide sufficient support for the entire structure of the Mishkan. Indeed, if one examines modern editions of the Talmud, there is an illustration that appears on the page. But where did it come from and more importantly what is its purpose? As we will show, the first edition to incorporate this diagram was the 1715 Amsterdam edition of the Talmud.

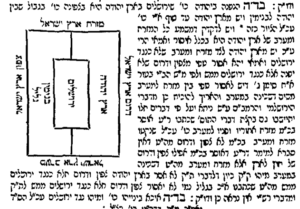

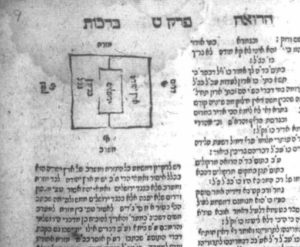

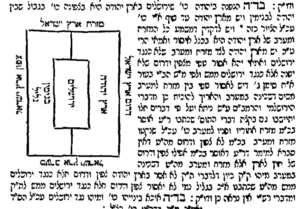

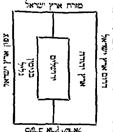

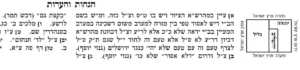

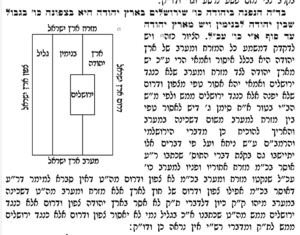

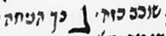

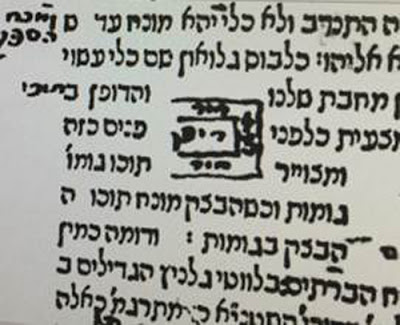

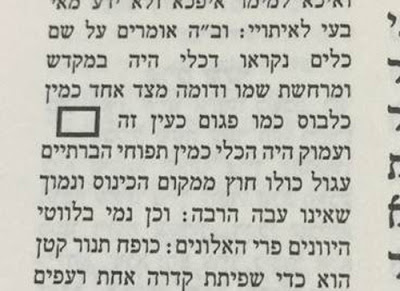

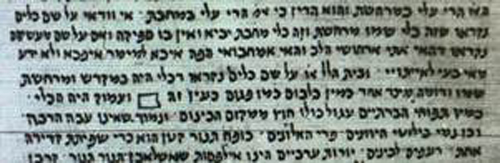

This is how it appears in the 1715 edition.

This image was reprinted in the Vilna Shas in a slightly clearer format although with the same detail and is a bit easier to analyze.

The picture primarily shows that there were three rods (“בריחים”) that connected one board to the next. The rods on the top and bottom went through outer rings, but the rod in the middle went through the width of the board.( “עובי הקרש“) It also shows the sockets on the bottom (“אדנים“) and the grooves (“ידות“) inserted in them which provided stability to the boards as they stood.

As discussed above, manuscripts of Gemarot though generally do not contain pictures, and a check on the invaluable website “Hachi Garsinan” shows that no manuscript of these pages has a picture to illustrate what a board looked like.[7] One might expect Rashi in his description of some of the statements of the Gemara to state his opinion and then write “כזה” (“ like this” ) Then we could expect to find an illustration in any of the number of Rashi manuscripts we have, and we could expect that this illustration (or an empty space for it) would appear in subsequent printed editions. Here we have none.[8]

The most relevant Rashi appears to his comments regarding how the boards stood miraculously.[9] But It does not discuss the fact that the middle rod went through the thickness of the board, but rather the miraculous nature of how the rod bent as it turned the corner. Another potential relevant Rashi explains the statement “the Sages taught, the bottoms of the beams (kerashim) were grooved and the sockets were hollow.” This deals with a completely different aspect of the beams which is how they were shaped on the bottom (and only according to Rabbi Nechemya). Thus, it is unsurprising that the manuscripts of Rashi do not include this diagram.

It was only in the 1715 edition does this illustration first appear. Yet, in the case of the picture of the keresh on Shabbos 98b, we do not find this picture in any of the sources identified by the Amsterdam publishers, not the Maharshal, Chochmas Manoach, Chidushei Halachos of Maharsha, or in Maharam Lublin.

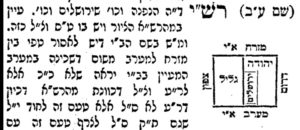

First, we must identify what the diagram is attempting to illustrate. Rather than the more common form of diagrams, this one is not an illustration tied to one of the rishonim, rather it is illustrating two statements of the Gemara, one in the middle of the Daf and one at the very bottom. This, despite the fact that the diagram appears close to Rashi’s commentary on the page, seemingly tying it to his commentary.

Instead, the illustration is the independent product of the Amsterdam publishers and intended to elucidate the text of the Gemara, what did the board system look like. The Mesivta edition of Oz Vehadar also understands that this picture illustrates the words והבריח התיכון בתוך הקרשים. They indicate that Tziyur 6 which except for the detail on the bottom looks very similar to the one in the Vilna Shas, illustrates that statement.

In truth, the main part of the picture showing the middle rod going through the width of the board is not at all aligned with a comment of Rashi. Understanding that it just tries to give a picture of the “קרש” will make it easier to understand for people who study this page. This illustration is designed to explicate the text of the Talmud itself and was the entirely the idea of the publishers of the Amsterdam Talmud.

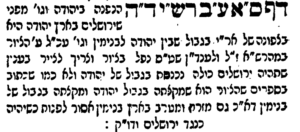

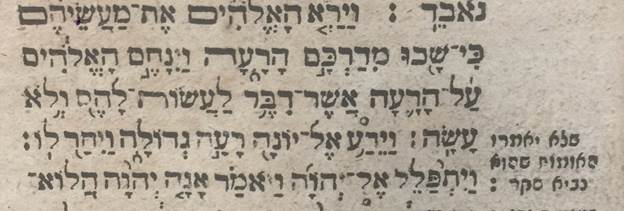

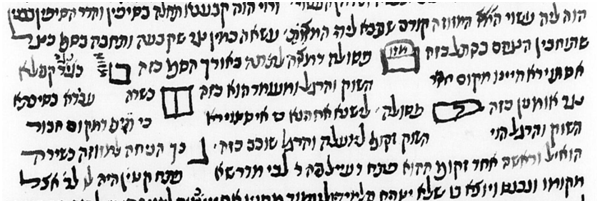

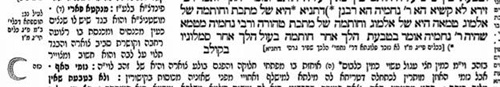

Why did the editors of the Amsterdam 1715 Shas insert a picture like this? Perhaps they were inspired by diagrams that appeared in a book called Omek Halacha by Jacob ben Simcha Bunim Koppelman which had just been reprinted in Amsterdam in 1710 and was even used in the fundraising campaign for this edition of the Talmud.[10] It has a picture of the grooves that fit into the sockets that is associated with the second aspect of this picture.

Yet, the Amsterdam publishers did not reprint the Omek Halakha’s crude diagram. Like the text and the other aspects of this edition, they included a much clearer and more detailed diagram that is infinitely more helpful in understanding the complicated text. Adding such a picture to a Daf of Gemara was a revolutionary act at that time and once added, it became part of Tzurat HaDaf that we have until today.

[1] As a matter of fact, there is a picture of the “קרש” in the Artscroll Stone Chumash, page 457, similar to the picture of the “קרש” in the Vilna Shas

[2] See Yaakov Spiegel, Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri: Hagahot u-Magihim (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan Univeristy Press, 2005), 312-17.

[3] Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: Complete Editions, Tractates, and Other Works and the Associated Presses from the Mid-17th Century through the 18th Century (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 75.

[4] Koppelman published another illustrated book, Ohel Yaakov. See Marvin Heller, The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus, Volume 2, (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 724-25.

[5] For additional information on this edition see Heller, Printing the Talmud, 74-89.

[6] The categories of work employed to build the Mishkan formed the basis for the Melachot of Shabbat. In this case, the boards of the Mishkan were transported from one location to another giving rise to issues relating to the domains created thereby.

[7] https://fjms.genizah.org/

[8] The manuscripts I checked on the KTIV website of the National Library of Israel were ones known as Parma 2097, Vatican 138, and Paris 324. All have no diagram in this entire Perek despite containing other diagrams of Rashi in other Perakim. (The two other manuscripts I checked of the total five that were available did not have diagrams in other Perakim either). The general website address for KTIV is https://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/en/manuscript

[9] In the book רש״י ,חייו ופירושיו“,כרך ב׳, הוצאת הקדש רוח יעקב, תשנ״ז” page 497, the author Rav Rephael Halpren states that there are 101 diagrams in Rashi included in the Vilna Shas, 51 of them in Masechet Eruvin. He then proceeds to enumerate all of them, including this one on Shabbat 98b. From the positioning of it on the page it certainly does look that way.

[10] Jacob ben Simcha Bunim Koppelman (1555–1594) was a talmudic scholar distinguished for his broad erudition and interest in secular sciences. Early in his life he embarked upon mathematical and astronomical studies, in addition to intensive occupation with traditional Jewish learning. He is the author of Omek Halakhah (Cracow, 1593). In it he elucidates the laws appertaining to Kilayim, Eruvin, etc., with the aid of diagrams and models. See here on Jacob ben Simcha Bunim Koppelman.

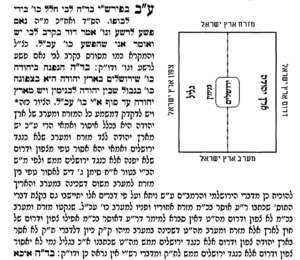

This is it as it appears in the first edition (Cracow 1593):

https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=45068&st=&pgnum=39