Rosh Hashana 23b – The Missing Map – Were We Deprived of a Map Drawn by Rashi?

Rosh Hashana 23b – The Missing Map – Were We Deprived of a Map Drawn by Rashi?

Eli Genauer

The Mishnah on Rosh Hashana 22b discusses the signal fires which were lit to inform the residents of Bavel of the Kiddush HaChodesh in Yerushalayim.

מַתְנִי׳: בָּרִאשׁוֹנָה הָיוּ מַשִּׂיאִין מַשּׂוּאוֹת…..

MISHNAH: Initially, after the court sanctified the new month they would light torches on the mountaintops, from one peak to another, to signal to the community in Babylonia that the month had been sanctified.[1]

The Mishnah continues

וּמֵאַיִן הָיוּ מַשִּׂיאִין מַשּׂוּאוֹת?

And from which mountains would they light the torches?

מֵֵהַר הַמִּשְׁחָה לְסַרְטְבָא וּמִסַּרְטְבָא לִגְרוֹפִינָא וּמִגְּרוֹפִינָא לְחַוְורָן וּמֵחַוְורָן לְבֵית בִּלְתִּיןִ..…

The Daf Yomi Advancement Forum provides us details of the places mentioned.[2]

From HAR HA’MISHCHAH- the Mount of Olives (to the east of the Old City of Yerushalayim)

To SARTAVA- a mountain in the Jordan valley

To GEROFINA- most probably a tower or rise heightened by Agrippa II near Ceasarea Philippi (modern-day Banias in northern Eretz Yisrael)

To CHAVRAN- Auran, a mountain located in the area of Aurantis east of the Jordan River

To Bait Baltin, which will be discussed on 23a and b. It is identified as BIRAM, a city on the border of Eretz Yisrael and Bavel

The Gemara 23a (on the bottom) and 23b (on the top) continues (Davidson Talmud):

וּמֵאַיִן הָיוּ מַשִּׂיאִין מַשּׂוּאוֹת כוּ׳ וּמִבֵּית בִּלְתִּין, מַאי בֵּית בִּלְתִּין? אָמַר רַב זוֹ בֵּירָם

What is this place called Beit Baltin? Rav said: This is the town called Biram.

The Gemara continues

תַּנְיָא רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר אוֹמֵר אַף חָרִים וּכְיָיר וּגְדֹר וְחַבְרוֹתֶיהָ אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי בֵּינֵי וּבֵינֵי הֲווֹ קָיְימִי אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי לְהָךְ גִּיסָא דְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל הֲווֹ קָיְימִי מָר חָשֵׁיב דְּהַאי גִּיסָא וּמָר חָשֵׁיב דְּהַאי גִּיסָא

It is taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar says: Torches were also lit at Ḥarim, and Kayar and Geder, and its neighboring places. There are those who say that the places added by Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar are located between the places mentioned in the Mishnah, whereas there are those who say that they are located on the other side of Eretz Yisrael, on the side nearer Babylonia. The Sage in the Mishnah enumerates the places found on one side of Eretz Yisrael, whereas the Sage in the Baraita enumerates the places found on the other side.

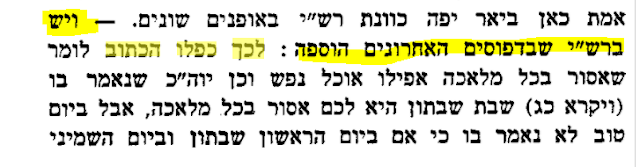

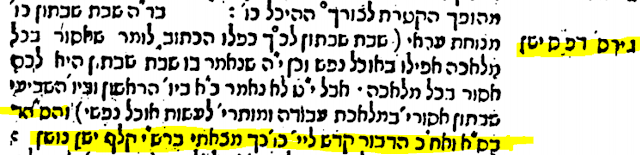

Rashi comments on the relationship of Eretz Yisroel to Bavel[3]

באידך גיסא – של א“י לצד בבל, שני צדדים של א“י נמשכין לצד בבל:

On one side – of Eretz Yisroel towards Bavel. There are two sides of Eretz Yisroel which extend to Bavel

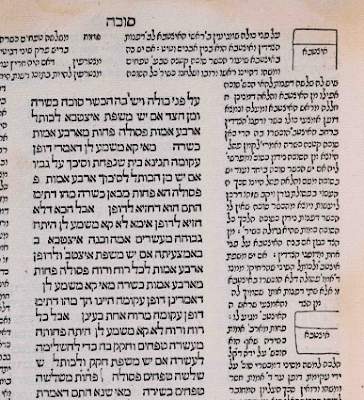

The language of Rashi is a bit unclear. It would be helpful if he included a map so we could visualize it better. As you can see, there is no map included in the authoritative text of the Vilna Shas.

A missing map of Eretz Yisroel and Bavel

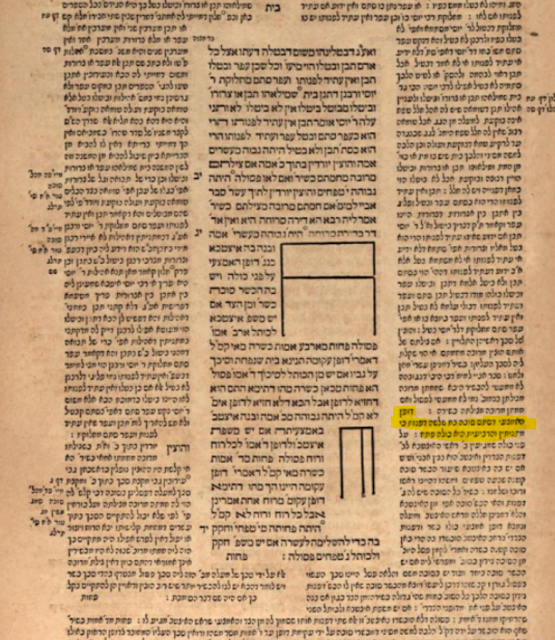

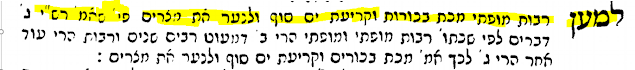

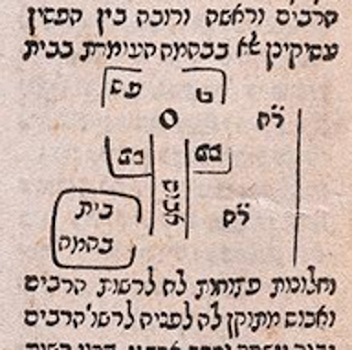

The first printed edition of Massechet Rosh Hashana was done by the Soncino family in Pesaro, Italy circa 1511.

It shows the two sides of Eretz Yisroel as it extends towards Bavel, with the places in the Mishnah listed in order on the top side, and the places listed in the Baraita on the bottom side. The map most correctly should have been placed underneath the Rashi which begins with the words באידך גיסא.

https://digitalcollections.jtsa.edu/islandora/object/jts%3A395714#page/59/mode/1up

What the map shows is the stretch of land which extended all the way from Eretz Yisroel to Bavel, and that there were two routes to get there.[4] The places named are different because the Tanna of the Mishna discusses the route on one side of Eretz Yisroel, and the Tanna of the Baraita discusses another route. Please note that even though it seems on the map that Bavel is to the west of Eretz Yisroel, this is only a convention of modern maps.[5] Clearly Rashi knew that Bavel was to the east as Eretz Yisroel was known as Ma’arava.

The first complete edition of the Talmud printed by Daniel Bomberg in Venice (c.1520-1523) retained the space for the diagram but left it blank.[6] This was carried through in his later printing of Rosh HaShana.

https://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=21208&st=&pgnum=47

The Giustiani edition (Venice 1548) also left a blank space

The space disappeared from the next printed edition, that of Basel 1579.

https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/zoom/22850827

It reappeared in an edition printed in Cracow in 1603, and it was now in the right place.

The next complete edition of the Talmud was printed in Amsterdam by Immanuel Benveniste (c.1644-1648). It did not contain a space, this despite its claim that it was patterned after the Giustiani edition of 1548.

The map (or an empty space) did not appear in the influential Amsterdam edition of 1717 and that most likely doomed it to oblivion in the printed Gemarot which followed[7].

Dr. Aharon Ahrend (“Rashi’s Commentary on Tractate Rosh Hashana: A Critical Edition,” Bialik Institute Jerusalem 2014) lists a number of manuscripts as his sources (3 complete, many partial) and does not indicate that this map is in any of them.[8] The Pesaro edition is the only one with this map. (p.218, last line”, במקור ״מ״ נוסף followed by a reproduction of the map- מקור ״מ״ is Pesaro).

The conclusion one might reach is that since no other manuscript contained this map, the manuscript on which the Pesaro edition was based had this map added by someone after Rashi’s time, perhaps in the margin to help the reader understand Rashi.

Is The Pesaro Edition of Masechet Rosh HaShana the Only Source For This Map?

Let us turn to the commentary of the Malechet Shlomo on Rosh Hashana. This commentary was first introduced in a new edition of Mishnayot printed by the Romm printers in Vilna. The Romm printers explain how they were able to access this heretofore unpublished manuscript which was found among the papers of the Chida.

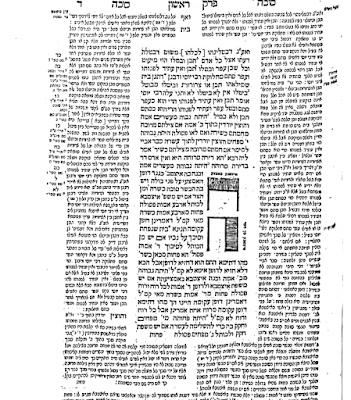

The author of the Malechet Shlomo was Rav Shlomo HaAdani (1567, Saana, Yemen-1625 Chevron, Eretz Yisroel) who wrote this commentary while he was in Chevron. He states that his two main teachers were Rav Betzalel Ashkenazi (the author of Shita Mekubetzet) and Rav Chaim Vital.

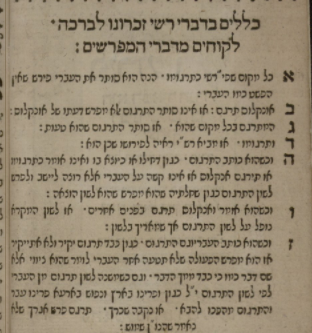

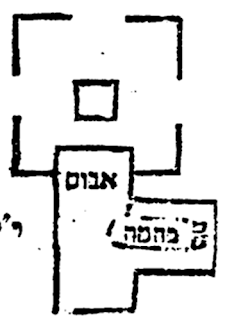

In this first printed edition of his commentary on our Mishna in Rosh Hashana we find a map very similar to the one in the Pesaro edition, only it is missing the cities on the top listed in the Mishna.[9] (Possibly because his “Kazeh” applies only to the cities on the other side of Eretz Yisroel and not the ones mentioned in the Mishnah).

This is the Ktav Yad of Rav Shlomo HaAdani from his commentary on Rosh Hashana:

Library of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute Warsaw Poland Ms. 267

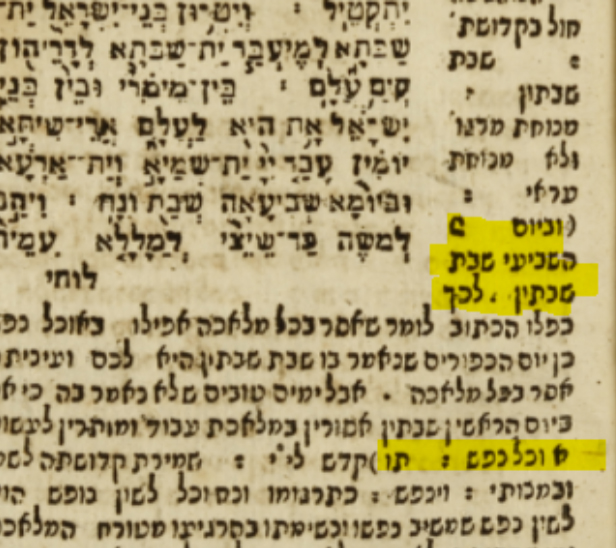

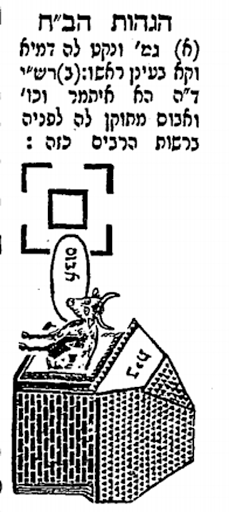

We mentioned that Rav Shlomo HaAdani was a Talmid of Rav Betzalel Ashkenazi. In his own copy of Rosh Hashana ( Bomberg Venice 1521) Rav Betzalel added many notes. Here is what 23b looks like in his Gemara:

The Russian State Library, Moscow, Russia Ms. Guenzburg 816

You can see that he drew in some sort of map in the empty space.

On the top of that same page, we find another map which he drew. The words on the top left are כל זה בספר יד.i[10] The Vilna Shas in its Acharit Davar says that he would do that quite often.

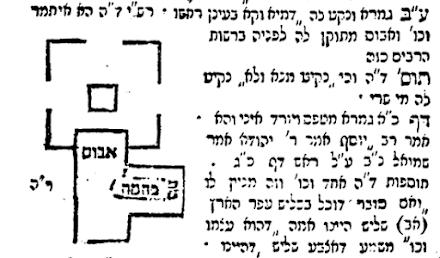

The Bach also drew in his Gemara, a Bomberg Rosh Hashana of 1531. The National Library of Israel owns a Gemara which was copied from the personal copy of the Bach.

The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel Ms. Heb. 24°174

Paleographic Note

אין זה אוטוגרף המחבר, ככל הנראה הועתק מהש“ס שלו

Here is how it looks

There seems to have been a concerted attempt in the 1500’s and 1600’s to retain some sort of map in the Rashi. Whether it appeared in the “original Rashi” we will likely never know.

[1] Sefaria, the William Davidson Talmud, English translation of Rav Steinsaltz, here.

[2] There are many other opinions as to where these places were.

[3] The Girsa in the Dibur HaMatchil in Rashi is slightly different than in the text of our Gemara.

[4] Rashi seems to indicate that Pumpedita (alternatively Nehardea) could be seen from the border of Eretz Yisroel whereas the Meiri indicates that once the fires got to the Israel/Bavel border, they were relayed from mountain to mountain in Bavel until Pumpedita.

[5] Please see Marc Shapiro’s article on map orientation which recently ran on the Seforim Blog here.

I specifically refer to footnote 4 at this website https://www.geographyrealm.com/map-orientation/, which states “Maps with south oriented towards the top of the map are known as south-up or reverse maps, since the map appears upside down to those used to a map orientation towards the north. In these maps, South is oriented the top of the map, east is towards the left of the map and west towards the right.”

[6] Dr. Edward Fram writes that “A blank space was left on the page suitable for adding a woodcut, but, whether for financial or technical reasons, the diagrams were not included until later printings” Edward Fram, “In the Margins of the Text, Changes in the Page of the Talmud,” in Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Scottenstein, ed. Sharon Lieberman Mintz et.al., Yeshiva Univ. Museum, New York: 2005, p. 91, n.4.

[7] My own research has shown this to be the case.

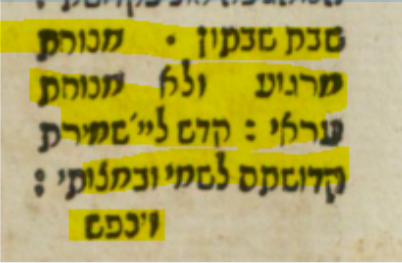

[8] Here is an example of a manuscript which does not contain the map:

The Palatina Library, Parma, Italy Cod. Parm. 2244

https://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/digitallibrary/pages/viewer.aspx?presentorid=MANUSCRIPTS&docid=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990000752410205171-1#|FL14863954

[9] This is taken from Mishnayot Zecher Chanoch (Jerusalem 1999) which is based on the Romm Vilna Mishnayot which were printed from 1887-1908.

[10] My thanks to Aharon for deciphering this and for all his other insightful comments.