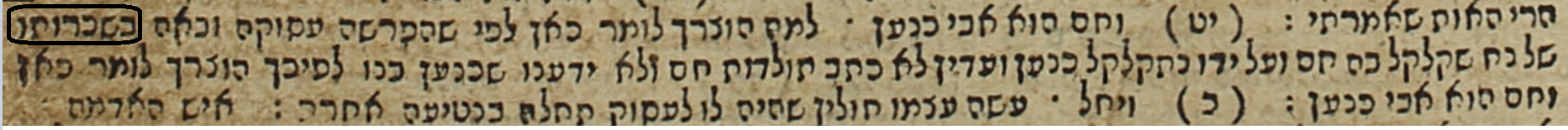

Rashi Devarim 26:17-18….. הֶאֱמַ֖רְתָּ and הֶאֱמִֽירְךָ֣

Eli Genauer

Rashi provides two explanations for a word in the Torah. Some scholars maintain that Rashi was not the source of the second explanation, rather it was derived from a “Taus Sofrim”. A close look at the manuscript witnesses reveals that the second explanation most likely did originate with Rashi.

Devarim 26

17. אֶת־ה’ הֶאֱמַ֖רְתָּ הַיּ֑וֹם לִהְיוֹת֩ לְךָ֨ לֵֽאלֹֹֹֹֹקים וְלָלֶ֣כֶת בִּדְרָכָ֗יו וְלִשְׁמֹ֨ר חֻקָּ֧יו וּמִצְוֺתָ֛יו וּמִשְׁפָּטָ֖יו וְלִשְׁמֹ֥עַ בְּקֹלֽוֹ׃

18. ה’ הֶאֱמִֽירְךָ֣ הַיּ֗וֹם לִהְי֥וֹת לוֹ֙ לְעַ֣ם סְגֻלָּ֔ה כַּאֲשֶׁ֖ר דִּבֶּר־לָ֑ךְ וְלִשְׁמֹ֖ר כָּל־מִצְוֺתָֽי

Rashi:

:האמרת … האמירך. אֵין לָהֶם עֵד מוֹכִיחַ בַּמִּקְרָא, וְלִי נִרְאֶה שֶׁהוּא לְשׁוֹן הַפְרָשָׁה וְהַבְדָּלָה — הִבְדַּלְתָּ לְךָ מֵאֱלֹהֵי הַנֵּכָר לִהְיוֹת לְךָ לֵאלֹהִים וְהוּא הִפְרִישְׁךָ אֵלָיו מֵעַמֵּי הָאָרֶץ לִהְיוֹת לוֹ לְעַם סְגֻלָּה, וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד וְהוּא לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת כְּמוֹ (תהלים צ”ד) יִתְאַמְּרוּ כָּל פֹּעֲלֵי אָוֶן

האמרה, האמירך are words for the meaning of which there is no decisive proof in Scripture. It seems to me, however, that they are expressions denoting “separation” and “selection”: “You have singled Him out from all strange gods to be unto you as God — and He on His part, has singled you out from the nations on earth to be unto Him a select people”. And I have found a parallel (lit., a witness) to it where it bears the meaning “glory”, as in (Psalms 94:4): “All wrongdoers glory in themselves”. (Sefaria translation)

We are faced with the following issues

- First Rashi says that he cannot find a word in Tanach similar האמרת … האמירך אֵין לָהֶם עֵד מוֹכִיחַ בַּמִּקְרָא, and he is therefore compelled to give his own interpretation וְלִי נִרְאֶה

- Rashi then seems to do an about face and says that he actually did find a comparable word in Tanach וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד. The Sefer Yosef Da’as terms this a Stirah.

- The textual witness that Rashi finds for האמירך is in Tehillim. On that word in Tehillim, Rashi gives an explanation and refers you to Ki Savo where he says the meaning is the same as his interpretation of וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד . There is a similar situation with Rashi’s interpretation of that word in Chagigah 3a and on Berachos 6a. On the other hand, in Gittin 57a, we find Rashi explaining our Pasuk in Ki Savo the same as his וְלִי נִרְאֶה Pshat here. We need to understand the relationship between the Rashi in Devarim and the Rashi on Tehillim. We need to understand the various Gemaros that explain either the Pasuk in Tehillim or the Pasuk in Devarim. We also need to understand why Rashi did not use the interpretation of Onkelos for the words האמרת ,האמירך which is taken directly from the Gemara in Chagigah.

- When we look at the various manuscripts of Rashi on this Pasuk we find a wide diversity of texts. Both the Sefer Yosef Da’as (Prague 1609) and Wolf Heidenheim (Chumash Me’Or Eynayim 1821) say that the words starting from וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד were not written by Rashi but were added later on by a student.[1] A study of the many Rashi manuscripts available today puts this conclusion into question

האמרת … האמירך. אֵין לָהֶם עֵד מוֹכִיחַ בַּמִּקְרָא, וְלִי נִרְאֶה שֶׁהוּא לְשׁוֹן הַפְרָשָׁה וְהַבְדָּלָה — הִבְדַּלְתָּ לְךָ מֵאֱלֹהֵי הַנֵּכָר לִהְיוֹת לְךָ לֵאלֹהִים וְהוּא הִפְרִישְׁךָ אֵלָיו מֵעַמֵּי הָאָרֶץ לִהְיוֹת לוֹ לְעַם סְגֻלָּה, וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד וְהוּא לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת כְּמוֹ (תהלים צ”ד) “יִתְאַמְּרוּ כָּל פֹּעֲלֵי אָוֶן”

The above seems to be the standard text of this Rashi. We find evidence of this entire text including the words “וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד” going back to Lisbon 1491, Venice 1524 and Sabionneta 1557:

Lisbon 1491

Venice 1524 ( and 1547)

Sabionetta 1557

Some “newer” Chumashim have the thought starting with וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד in parentheses:

Amsterdam 1901-A.S Onderwijzer – (The Dutch translation of Rashi also has this portion in parentheses)

Chumash Torah Temimah- Vilna -1904

The Artscroll Stone Chumash has the words “דבר אחר” immediately preceding the word “וּמָצָאתִי” all in parentheses.

I have also seen it recorded with just the דבר אחר in parentheses.

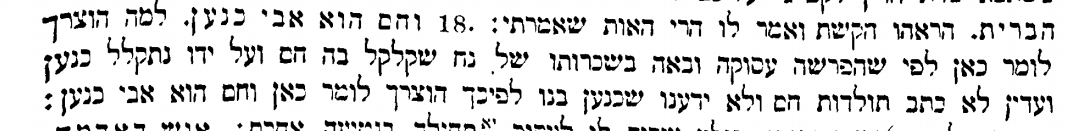

The Sefer Yosef Da’as (Cracow 1608) concludes that the words starting from וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד were not written by Rashi[2] ״רק איזה תלמיד כּתבו על הגליון והמדפיס חשב שהם דברי רש״י״

This is also the conclusion of Wolf Heidenheim:

Chumash Meor Einayim, Rödelheim : 1821 (ed. Wolf Heidenheim)

Heidenheim echoes the words of the Yosef Daas[3]:

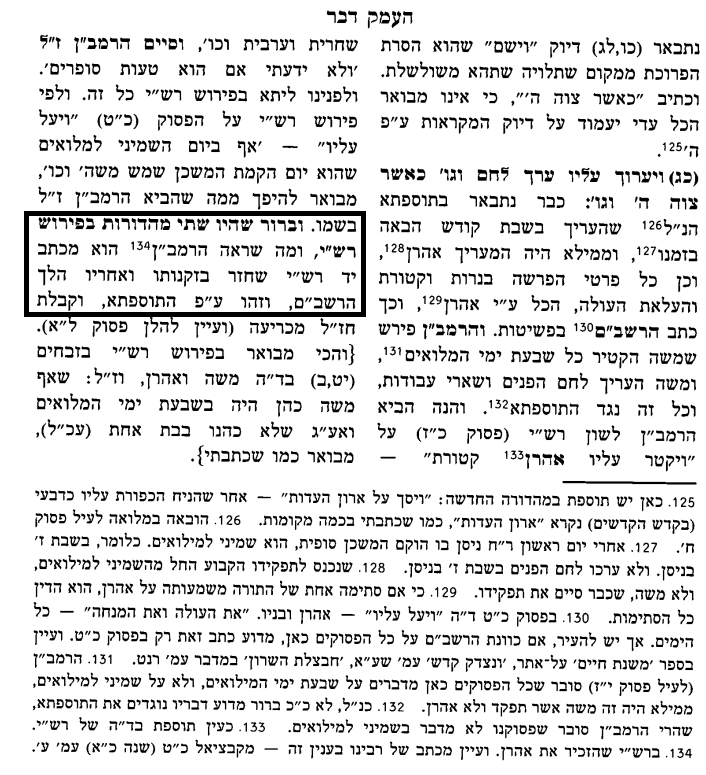

What was the Original Girsa of Rashi?

Here is some background on the manuscript known as Leipzig 1. It was not available to Yosef Da’as, Wolf Heidenheim or later on, to A J. Berliner and to Artscroll Saperstein.

From Chachmei Tzarfat HaRishonim by Prof. Avraham Grossman.[4]

עמ’ 187 :כלי עזר חשוב לבירור הנוסח המקורי של פירוש רש”י לתורה הוא כתב-יד לייפציג .פירוש רש”י לתורה שבכתב-יד זה הוא ככל הנראה הנוסח הקרוב ביותר על המקור שכתב רש”י, המצוי כיום בידינו, אף שגם בו יש השלמות מאוחרות ושיבוש העתקה. בשולי פירוש רש”י לתורה שבכתב-יד זה נרשמו הגהות רבות ערך של תלמידו ר’ שמעיה, ונידון בהן בפירוט בסקירת מפעלו של ר’ שמעיה

עמ’ 188 :ר’ מכיר העיד פעמים הרבה שהחזיק בידיו את כתב היד של פירוש רש”י לתורה שבו כתב ר’ שמעיה בעצמו את הגהותיו

. עמ’ 191 :מדבריו של ר’ שמעיה עולה כי לא זו בלבד שרש”י בעצמו הכניס תקונים לפירושיו והגיהם, אלא שביקש גם ממנו לעשות כן

“הגהות רבינו שמעיה ונוסח פירוש רש”י לתורה” – תרביץ ס׳ (תשנ״א)

” לדעתי ראוי [כ”י ליפזיג 1] להיחשב כמקור החשוב ביותר המצוי כיום בידינו וככלי העזר העיקרי לכל חקירה בשאלת הנוסח של פירוש רש”י לתורה”

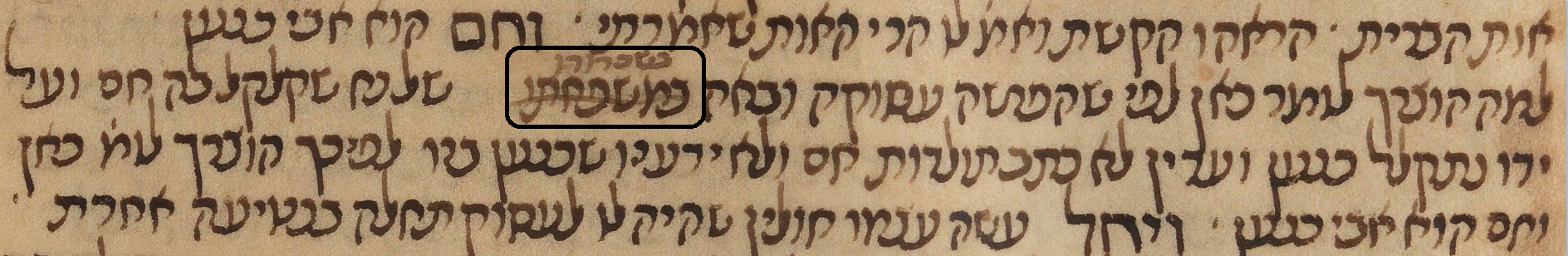

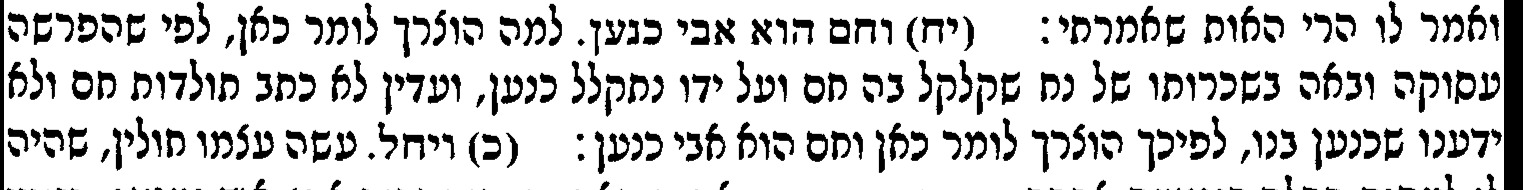

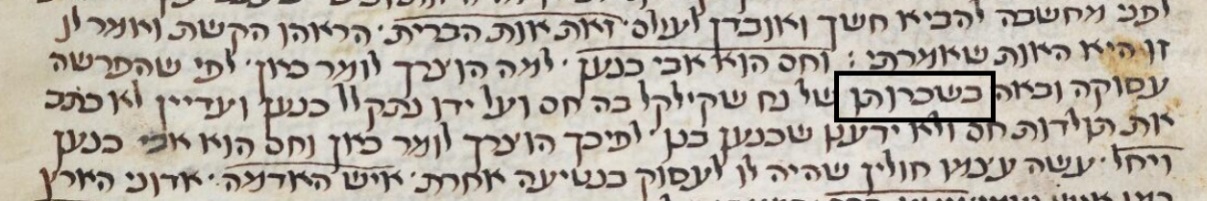

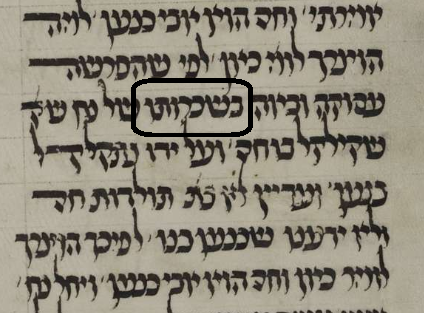

This is how it is recorded in Leipzig 1. The order is reversed and Lashon Tiferet comes first followed by Lashon Havdalah.

(The entire page.)

.יז-יח האמרת, האמירך – לשון תפארת כמו יתאמרו כל פעלי און אין להם עד במקרא, ולי נר’ שהם לשון המשכה והבדלה הם, הבדלתו מאלקי הנכר להיות לך לאלקים, והוא הפרישך אליו מעמי הארץ להיות לך לעם סגולה

We find that the interpretation that Rashi seems to give as an afterthought, is now the first interpretation.

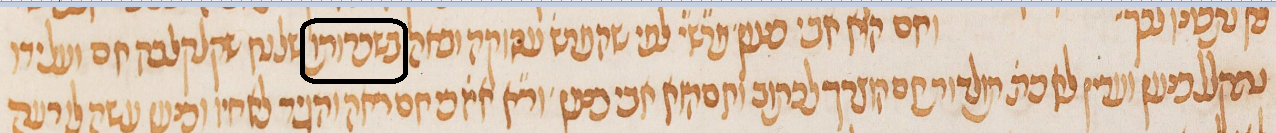

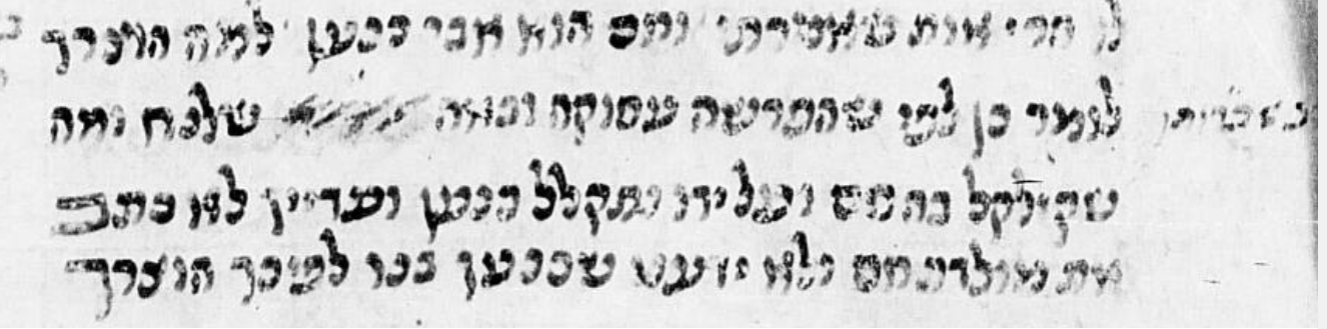

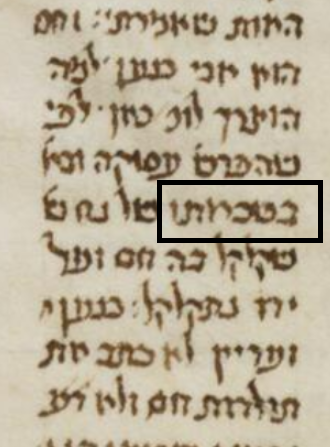

Berlin 1221- Has only לשון תפארת

האמרת, האמירך – לשון תפארת כמו יתאמרו כל פעלי און

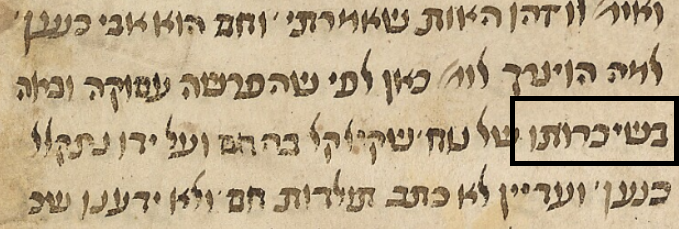

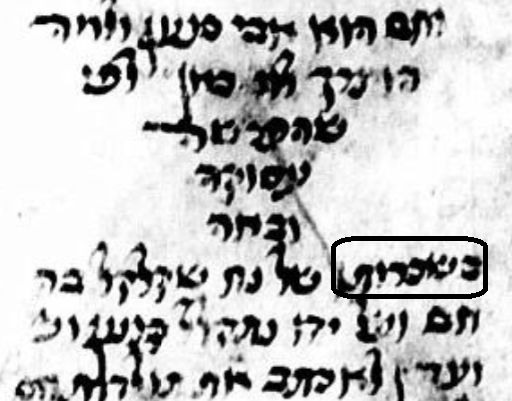

On the other hand, Munich 5 has only Lashon Havdalah with no Lashon Tiferes – the complete opposite of Berlin 1221.

Because of its age (1194) another important manuscript is Oxford UCC 165 ( Neubauer 2440). It records the Rashi the same as Munich 5.

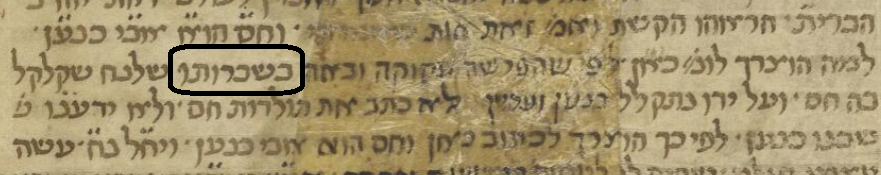

To summarize: Lepzig 1 has both comments with Lashon Tiferes first. Berlin 1221 has only Lashon Tiferes and Munich 5 and Oxford UCC 165 only have Lashon Havdalah.[5]

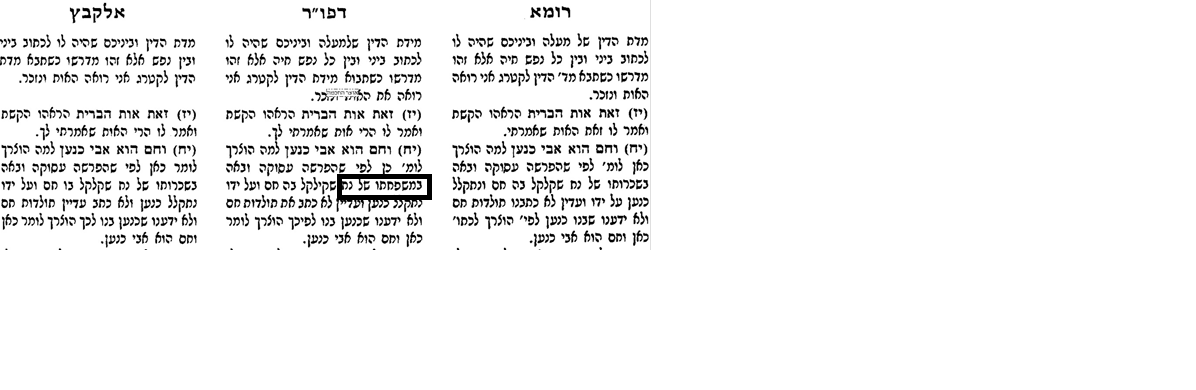

An analysis of other manuscripts by Al HaTorah yields the following, along with a possible approach to reconciling the textual variances. .

From Al Hatorah.org:

10 ה 10ה הדיון בהמשך של “אין להם עד… לעם סגולה” חסר בכ”י ברלין 1221, וינה 23, וינה 24

בכ”י פרמא 181, מינכן 5, פריס 155, ברלין 1222, וטיקן 94, ליידן 1, המצב הפוך, וחסר “לשון תפארת כמו יתאמרו כל פעלי און” (בפרמא 181 הוא נוסף בגיליון אחר “לעם סגולה”, ובברלין 1222 הגיליון סומן לאחר “האמרת והאמירך” וכפי שהוא מופיע בטקסט בלייפציג 1). בכ”י ויימר 652 “מצאתי להם עד לשון תפארה יתאמרו כל פועלי און” מופיע בסוף הפירוש לאחר “לעם סגולה”, וכן באופן מקוטע בפריס 154. כ”י פריס 49 דומה לכ”י לייפציג. ועיין במחלוקתם של א’ טיוטו בתרביץ ס”א:א’ עמ’ 92-91 וא’ גרוסמן בתרביץ ס”א:ב’ עמ’ 308.

יש שתי דרכים שבהן ניתן להסביר ולשחזר את התהליך שאירע בפירוש רש”י כאן:

(א) הפירוש הראשון (“לשון תפארת”) הוא של רש”י עצמו, והפירוש השני (“לשון המשכה / הפרשה והבדלה”) הוא תוספת של ר”י קרא. אפשרות זו נתמכת ע”י כ”י מוסקבה 1628 – עיין דברינו על פירוש ר”י קרא לדב’ כ”ו:י”ז-י”ח.

(ב) שני הפירושים הסותרים נכתבו ע”י רש”י עצמו. הפירוש הראשון (“לשון תפארת”) הוא של רבותיו של רש”י, והפירוש השני (“לשון המשכה / הפרשה והבדלה”) הוא של רש”י עצמו. אפשר שכ”י פרנקפורט 19 תומך באפשרות זו. שם כתוב: “האמרת, האמירך – לשון תפארת כמ’ יתאמרו כל פועלי און וכמ’ בראש אמיר כך הורו מורים [אולי צ”ל “מורי”]. ואני אומ’ שאין להם עד במקום [צ”ל “במקרא”]. ולי נראה שהוא לשו’ הפרשה והבדלה, הבדלתו לך מאלהי הנכר להיות לך לאלהים, והוא הפרישך אליו להיות לו לעם סגולה.”

Analysis of Gemaros and of Rashi in Tehillim:

The first Pshat וְלִי נִרְאֶה in the standard Rashi is that the Jewish people have set aside Hashem to be there G-d (לְשׁוֹן הַפְרָשָׁה וְהַבְדָּלָה ) and He has set aside the Jewish people as His people. This is similar to the explanation Rashi gives for our Pasuk on Gittin 57b. The Gemara tells the story of the woman whose seven sons refused to bow down to an idol, each one quoting a Pasuk to back up his decision.

‘אתיוהו לאידך אמרו ליה פלח לעבודת כוכבים אמר להו כתוב בתורה (דברים כו, יז) את ה’ האמרת וגו’ וה’ האמירך היום וגו

They then brought in yet another son, and said to him: Worship the idol. He said to them: ( I cannot do so,) as it is written in the Torah: “You have האמרת Hashem this day to be your G-d…and Hashem has האמירך you this day to be a people for His own possession” (Deuteronomy 26:17–18)

Rashi explains האמרת – ייחדת – set aside . This is very similar to the Lashon he uses in Ki Savo of הִבְדַּלְתָּ לְךָ מֵאֱלֹהֵי הַנֵּכָר לִהְיוֹת לְךָ לֵאלֹהִים

On the other hand, the Pasuk where he writes וּמָצָאתִי לָהֶם עֵד וְהוּא לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת כְּמוֹ

“יִתְאַמְּרוּ כָּל פֹּעֲלֵי אָוֶן”:, in Tehillim 94:4..there Rashi gives his second explanation to our words in Ki Savo

The thought expressed in Tehillim is how long will Hashem tolerate the fact that evildoers brag about their actions. It is clear that יִֽ֝תְאַמְּר֗וּ means “praise themselves”.

עַד־מָתַ֖י רְשָׁעִ֥ים ׀ יְהוָ֑ה עַד־מָ֝תַ֗י רְשָׁעִ֥ים יַעֲלֹֽזוּ׃

How long shall the wicked, O LORD, how long shall the wicked exult,

יַבִּ֣יעוּ יְדַבְּר֣וּ עָתָ֑ק יִֽ֝תְאַמְּר֗וּ כָּל־פֹּ֥עֲלֵי אָֽוֶן׃

shall they utter insolent speech, shall all evildoers pride themselves?

Rashi in Tehillim

יתאמרו. ישתבחו כמו (דברים כו) האמרת והאמירך

In Ki Savo, Rashi seems to say he can’t find a witness for this word הֶאֱמַ֖רְתָּ in all of Mikra and then Rashi himself in Tehillim explains the word as meaning something very similar to לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת and refers you to the Pesukim in Devarim. And in Tehillim, he gives a different explanation for the Pasuk in Ki Savo than he gives on Gittin 57b.

Chagigah 3a on the bottom of the page

עוד דרש (דברים כו, יז) “את ה’ האמרת היום”,” וה’ האמירך היום “אמר להם הקב”ה לישראל אתם עשיתוני חטיבה אחת בעולם ואני אעשה אתכם חטיבה אחת בעולם

Rashi comments

האמרת – שבחת כמו יתאמרו כל פועלי און (תהילים צ״ד:ד׳) ישתבחו, שדרכן צלחה:

Again we have the word יתאמרו or האמרת meaning something like לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת (שבחת ) and not לְשׁוֹן הַפְרָשָׁה וְהַבְדָּלָה

Rashi seems to be giving us a translation of the word האמרת as opposed to the Gemara’s Drasha on this word

However, Onkelos uses the word חֲטַבְתָּin his translation of the word He’emircha

יָת הּ’ חֲטַבְתָּ יוֹמָא דֵין לְמֶהֱוֵי לָךְ לֶאֱלָק’ וְלִמְהַךְ בְּאָרְחָן דְּתָקְנָן קֳדָמוֹהִי וּלְמִטַּר קְיָמוֹהִי וּפִקּוּדוֹהִי וְדִינוֹהִי וּלְקַבָּלָא בְמֵימְרֵיהּ:

והּ’ חָטְבָךְ יוֹמָא דֵין לְמֶהֱוֵי לֵיהּ לְעַם חַבִּיב כְּמָא דִי מַלִּיל לָךְ וּלְמִטַּר כָּל פִּקּוּדוֹהִי:

חטיבה is like in the words “Chotaiv Aitzecha.”

The word חטיבה is translated by Steinsaltz as a “single entity.”

This is Steinsaltz’s translation of the Gemara:

You have made Me a single entity in the world, (as you singled Me out as separate and unique). And (therefore) I will make you a single entity in the world, (as you will be a treasured nation, chosen by God.)

This is more in line with the idea of

לְשׁוֹן הַפְרָשָׁה וְהַבְדָּלָה — הִבְדַּלְתָּ לְךָ מֵאֱלֹהֵי הַנֵּכָר לִהְיוֹת לְךָ לֵאלֹהִים וְהוּא הִפְרִישְׁךָ אֵלָיו מֵעַמֵּי הָאָרֶץ לִהְיוֹת לוֹ לְעַם סְגֻלָּה

We have a similar outcome in Rashi in Berachos 6a where the Pasuk in Ki Savo is also quoted. There too Rashi explains the word האמיר in our Pasuk in Ki Savo as meaning praise.

ומי משתבח קודשא בריך הוא בשבחייהו דישראל אין דכתיב את ה׳ האמרת היום וכתיב וה׳ האמירך היום

Is the Holy One, Blessed be He, glorified through the glory of Israel? Yes as it is stated: “You have האמרת, this day, that the Lord is your God, And it states: “And the Lord has האמירך, this day,…(Deuteronomy 26:17–18).

Rashi comments on the word האמרת:

האמרת – לשון חשיבות ושבח כמו יתאמרו כל פועלי און (תהילים צ״ד:ד׳) ישתבחו

The Lubavitcher Rebbe summarizes some of the problems with the Rashi text as we have it, and adds another issue as to why Rashi didn’t explain the word as coming from the Shoresh “Omair” as Ibn Ezra did.

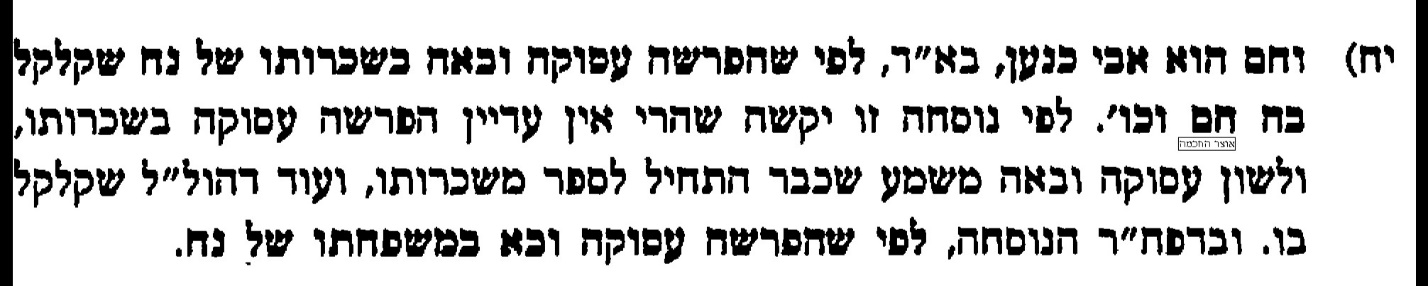

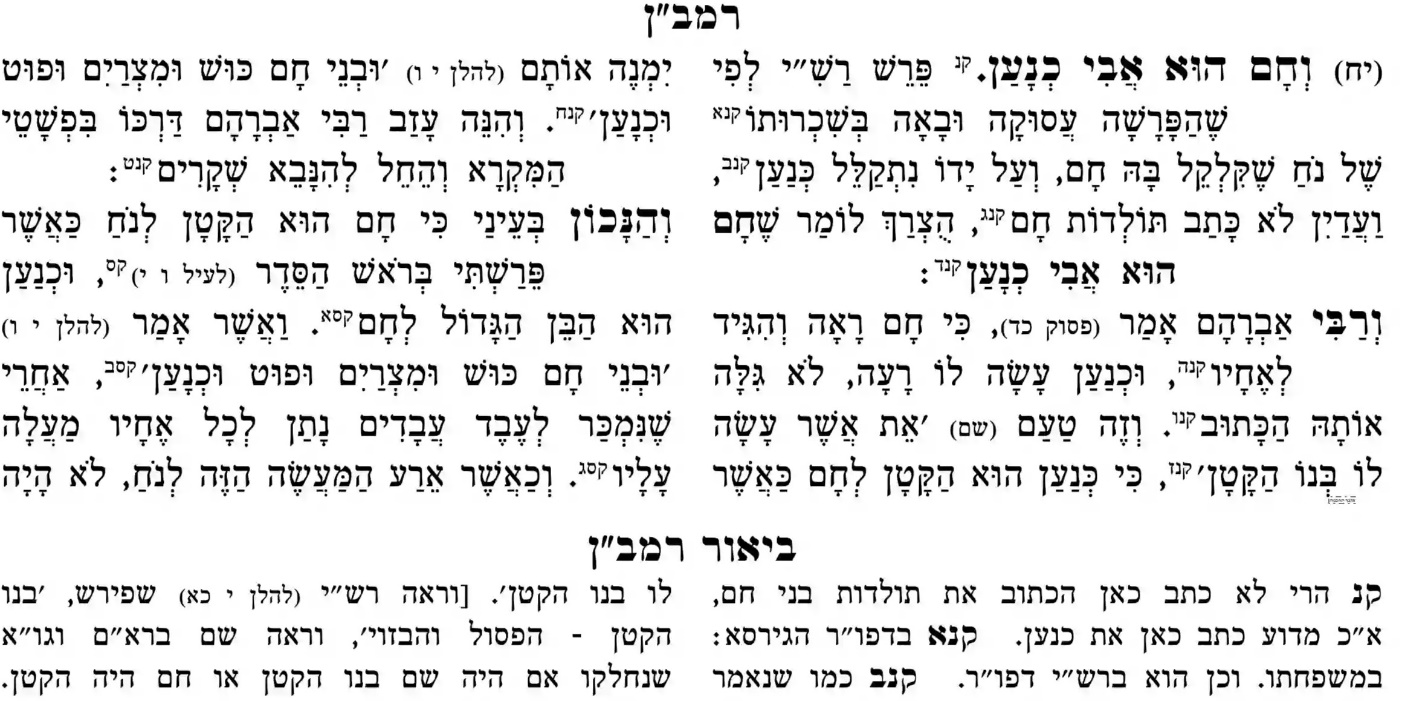

Likutei Sichos Chelek Tes – The Sicha is in Yiddish only – This is a summary in Hebrew:

קשה לפרש ש”האמרת” הוא לשון אמירה (כי האמירה אינה בכל יום), ו”אין להם עד מוכיח במקרא” שיכריח לפרש כן. אך “ומצאתי להם עד” שהוא לשון תפארת

ברש”י (כ”ו י”ז): “האמרת והאמירך: אין להם עד מוכיח במקרא. ולי נראה שהוא לשון הפרשה והבדלה, הבדלתו לך מאלוקי הנכר להיות לך לאלוקים והוא הפרישך אליו מעמי הארץ להיות לו לעם סגולה. ומצאתי להם עד והוא לשון תפארת כמו יתאמרו כל פועלי און”

.1 צריך להבין איך אומר בהתחלה ש”אין להם עד מוכיח”, הרי מיד אח”כ אומר “ומצאתי להם עד”?

.2ומדוע אינו מפרש שהוא לשון אמירה – כמו שפירש ר’ יהודה הלוי והובא באבן עזרא – שאז יוצא שיש להם ריבוי מוכיחים במקרא

והביאור: רש”י מדגיש ש”אין להם עד מוכיח במקרא”, זאת אומרת שישנה קושי לפרש ש”האמרת” הוא לשון תפארת ואמירה, ורק אם היה להם עד מוכיח – שיכריח לפרש כן – הי’ מפרש כן. והקושי שישנו בפירוש אמירה הוא שהפסוקים “האמרת היום” “וה’ האמירך היום” באים בהמשך להפסוק “היום הזה ה’ אלוקיך מצוך” – שקאי על כל יום, וא”כ אי אפשר לפרש ש”האמרת” הוא לשון אמירה, כי רק כשהנהגת בנ”י הוא כראוי פועלים שה’ יאמר שהוא רוצה להיות להם לאלוקים, ורק כשהנהגת ה’ עם בנ”י הוא באופן ניסי, אומרים בנ”י שהם עם סגולה. ולכן מפרש רש”י “לשון הפרשה והבדלה”, דענין זה אינו תלוי בהנהגת בנ”י (דגם כשאינם עושים רצונו של מקום יודעים שה’ הוא אלוקיהם(

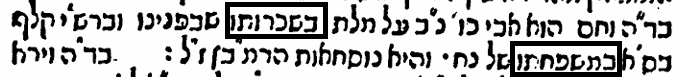

This is how this Pasuk is presented in the Artscroll Saperstein Rashi[7]:

The comments end (4.) with “Yosef Da’as concludes they were interpolated by someone other than Rashi” indicating that Rashi in Ki Savo does not include the concept of האמרת meaning לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת. This is directly in contradiction to Leipzig 1.

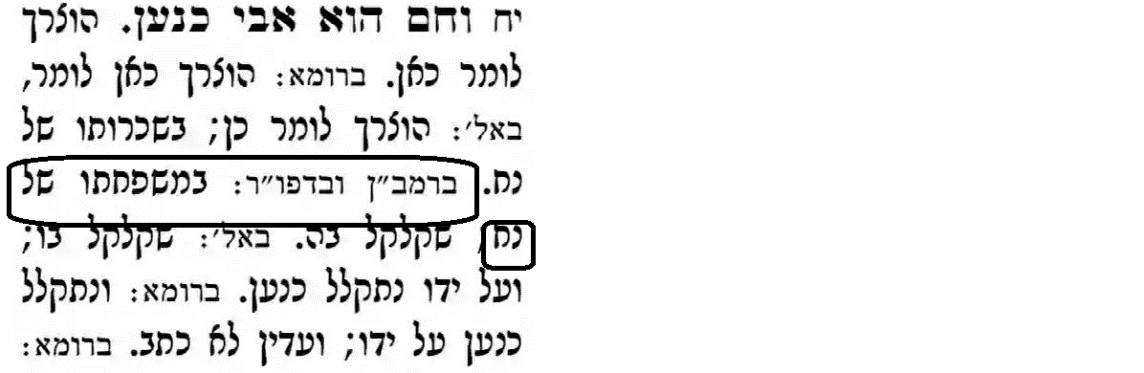

What does Avraham Berliner in Zechor L’Avraham (Berlin 1867) say?

Firstly, Berliner states that the author of Yosef Da’as only had one Rashi manuscript and therefore his (Berliner’s) rendering of Rashi is more accurate.

This is Berliner on our Pasuk:

In his introduction, Berliner mentions all the Kisvei Yad he had and includes Munich 5 but he does not include Leipzig 1.

In conclusion, if you look at many early manuscripts, the idea that האמרת means לְשׁוֹן תִּפְאֶרֶת is definitely there. As a matter of fact, in Lepzig I it comes first and other manuscripts, (such as Berlin 1221) don’t even have the explanation of הבדלה. Both Leshonos could come from Rashi.

[1] The Artscroll Sapirstein Rashi quotes Yosef Da’as as the last of its comments.

[2] The author of Yosef Da’as:

המחבר היה מחכמי פראג שנולד בפראג בשנת ש”ם ונפטר שם בשנת תי”ד. הוא היה תלמידם של גדולי חכמי פראג, והוא מביא הרבה תורה מהם בספר, וכן הוא כותב מאחרי השער שהספר נדפס בהסכמתם. המחבר עמל לזקק את הטעויות שנפלו בפירוש רש”י על התורה, ולמטרה זו השתמש בחומשים עתיקים, וכן בכתב יד עתיק מהמאה ה-14 שמצא בלובלין. ליד כל תיקון והערה, הוא מציין את המקור

[3] A.J. Rosenberg also weighs in on this (Judaica Press Rashi in English) as follows:

[4] There is a Machlokes on Grossman’s opinion which is still open 308 ‘ועיין במחלוקתם של א’ טיוטו בתרביץ ס”א:א’ עמ’ 92-91 וא’ גרוסמן בתרביץ ס”א:ב’ עמ.

[5] Munich 5 is also supposed to be quite authoritative. Here is a quote from Prof. Marc B. Shapiro cited in Hakirah 26:

The copyist of the Rashi manuscript was not some anonymous person, but R. Solomon ben Samuel of Würzberg. R. Solomon was an outstanding student of R. Samuel he-Hasid and a colleague of R. Judah he-Hasid. He was also a student of R. Yehiel of Paris, and R. Solomon’s son was one of the participants in the 1240 Paris Disputation together with R. Yehiel. R. Solomon wrote Torah works of his own and he may be identical with R. Solomon ben Samuel, the author of the piyyut סלחתי ישמיענו that is recited in Yom Kippur Neilah. ArtScroll, in its Yom Kippur Machzor, p. 746, tells us that סלחתי ישמיענו was written by “R’ Shlomo ben Shmuel of the thirteenth-century.”

[6] Explanation of Ibn Ezra. First, he says it a language of exaltation. (similar to Shavachta and Lashon Tiferes) Then he quotes Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi as saying the source is ויאמר . Ibn Ezra prefers this explanation. This is referred to by the Lubavitcher Rebbe as the most direct explanation.

האמרת. מלשון גדולה וקרוב מגזרת בראש אמיר ויאמר רבי יהודה הלוי הספרדי ,נשמתו עדן, כי המלה מגזרת ויאמר והטעם כי עשית הישר עד שיאמר שהוא יהי’ אלהיך גם הוא עושׁה לך עד שאמרת שתהי’ לו לעם סגולה ויפה פירש והנה תהיה מלת האמרת פעל יוצא לשנים פעולים

The Hebrew word “bespoke” carries connotations of exaltation. Compare, “in the top of the uppermost bough” [Isaiah 17: 6]. The Spaniard Rabbi Yehudah HaLevy — may his soul rest in Gan Eden — explained how the word is related to the verb “to say”: the sense of the passage is that you have done all that is proper, to the point that you cause other people to say “He will be your God”; and He will likewise act toward you so as to cause you to say that you will be His treasured people. According, the verb “to bespeak” takes both a direct and an indirect object.

[7] Artscroll’s sources are given as follows:

Variant readings [of the text of Rashi] are either enclosed in braces or appear in the footnotes, along with the sources from which Rashi drew his commentary. Among the earliest printed editions (incunabula) from which the variant readings are taken are the editions printed in: Rome (undated, possibly 1470), Reggio di Calabria, Italy (also called defus rishon, “first printed edition”; 1475); Guadalajara, Spain (Alkabetz edition, 1476); Soncino, Italy (1487); Zamora, Spain (1487). The Venice (Bomberg) edition of 1517-18 was the first edition of Mikraos Gedolos with Scripture, Targum, Rashi and all the standard commentaries. In the course of researching the variant readings of Rashi, we found valuable resources in the recently published Yosef Hallel (Rabbi Menachem Mendel Brachfeld; Brooklyn; 5747/1987); and, for the Bereishis volume, the ongoing Chamishah Chumshei Torah – Ariel/Rashi HaShalem (Jerusalem, vol. 1 – 1986, vol. 2 – 1988, vol. 3 – 1990).

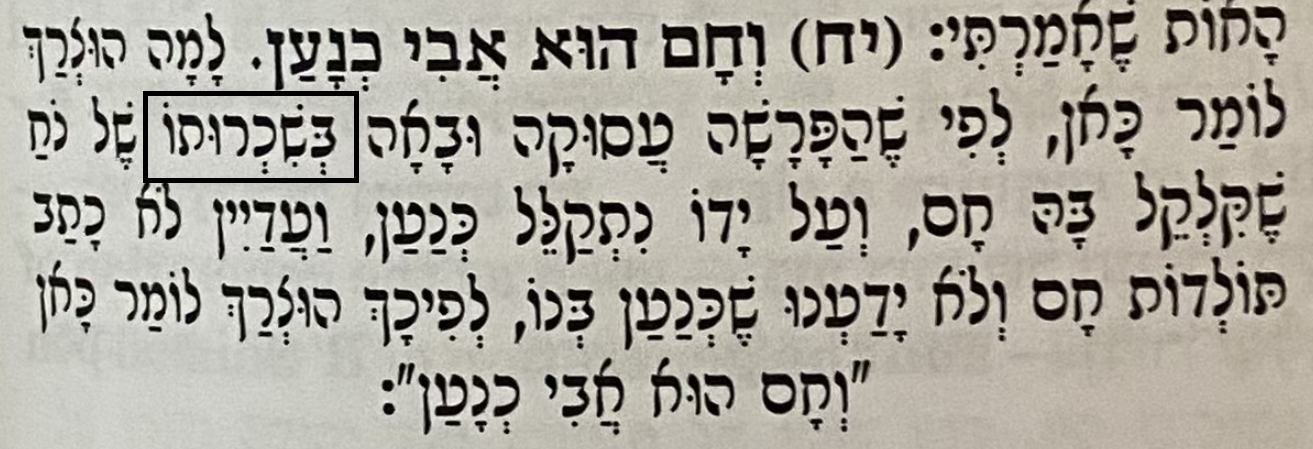

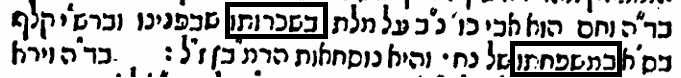

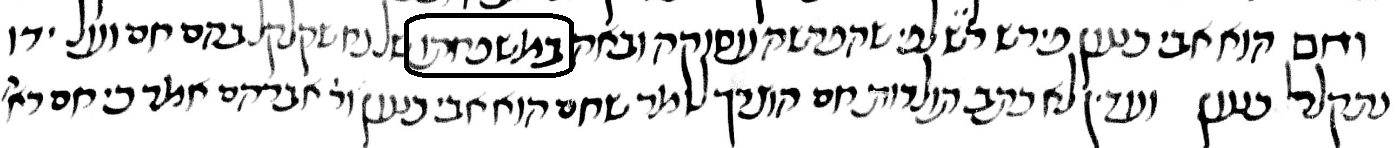

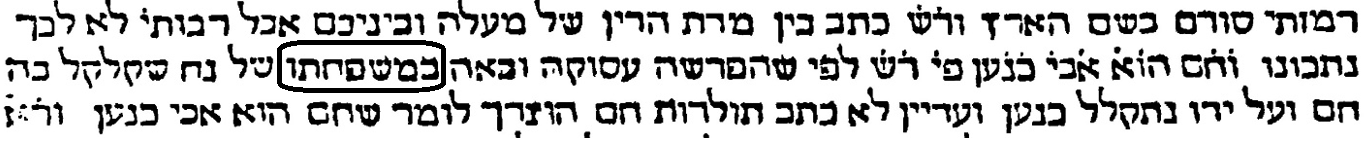

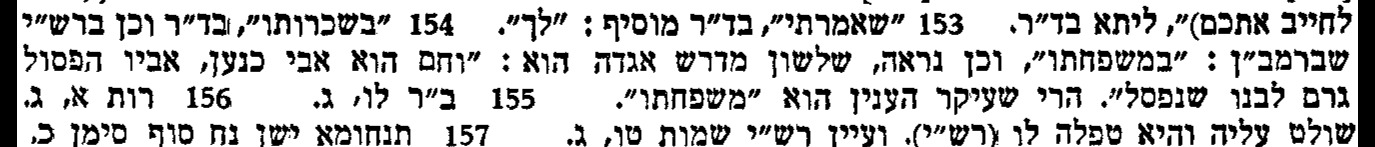

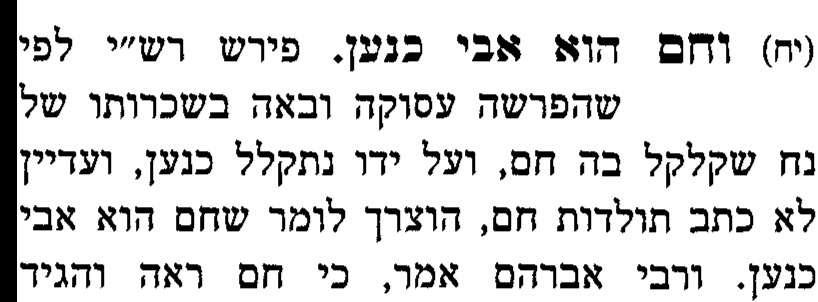

The Netziv in Shemot 40:23 cites a comment of the Ramban in which he quotes Rashi and says that our text of Rashi is different. He proposes that there were two Mahdurot of Rashi, of which Ramban had the first Mahadura and we have the second one. In that second Mahadura, Rashi reversed himself from what he said in the first Mahadura. It is possible that this occurred here- in the first Mahadura, Rashi wrote במשפחתו and that is the Mahadura which Ramban had. Later on, Rashi changed it to בְּשִׁכְרוּתו and that has become the standard Girsa:

The Netziv in Shemot 40:23 cites a comment of the Ramban in which he quotes Rashi and says that our text of Rashi is different. He proposes that there were two Mahdurot of Rashi, of which Ramban had the first Mahadura and we have the second one. In that second Mahadura, Rashi reversed himself from what he said in the first Mahadura. It is possible that this occurred here- in the first Mahadura, Rashi wrote במשפחתו and that is the Mahadura which Ramban had. Later on, Rashi changed it to בְּשִׁכְרוּתו and that has become the standard Girsa:

%20(1)_html_699a7594.jpg)

%20(1)_html_mf930eff.jpg)

%20(1)_html_a83250b.png)

%20(1)_html_6f0244b5.png)

%20(1)_html_635ceb31.png)

%20(1)_html_22fab565.png)