Haftaros of Vayetze and Vayishlach – A Mistake Rectified[1]

By Eli Duker

There had been one practice throughout the Jewish world concerning the Haftara of Vayishlach until the print revolution. The book of Ovadia is the Haftara listed in every Haftara list, including the one in the Rambam’s Seder HaTefillos in the Mishneh Torah, MS Ginsburg Moscow of the Machzor Vitry,[2] Etz Chaim (written in London on the eve of the Edict of Expulsion),[3] Abudarham,[4] and the list of Rabbi Shmuel Hanagid, cited in the Sefer HaEshkol.[5] It is also the Haftara in the “Emes” piyyut written by Rabbi Shmuel Hashelishi[6] and the “Zulas” piyyut written by Rabbi Yehuda B’Rabi Binyamin.[7] This is also the Haftara listed in all chumashim in manuscript[8] and in all Cairo Geniza fragments9 that I have seen.

This was also the practice of those who followed the triennial cycle in Eretz Yisrael,[10] the Haftara for the sidra of Vayishlach Yaakov was from the book of Ovadia. The reason for the Haftara is clearly due to it being a prophecy about Edom, and Edom is discussed in depth in the parasha.

The universal practice in all communities was to read from the book of Hoshea for the Haftara of Vayetze, but not everyone read the same verses. In all Geniza fragments[11] the Haftara begins at 11:7, “Ve’ami seluim.” In the fragments with a clear end to the Haftara I have found 3 that end at 12:14,[12] which is similar to what appears in the list of in the Rambam’s Seder HaTefillos, making it a classic Haftara of exactly twenty-one pesukim. One source has it end at 13:4,[13] which is the “Zulas” piyyut written by Rabbi Yehuda B’Rabi Binyamin for this parasha,[14] as well as in the Sefer HaShulchan, written by a student of the Rashba. The reason for the Haftara is due to the verse “Vayivrach Yaakov ,” which is clearly related to the events of the parsha, as well as, possibly, the mention of “Bes El” in 12:5

There were two different Ashkenazi practices in the pre-printing era. One was to begin at 12:13, “Vayivrach Yaakov ,” and to read until the end of the book. This is the Haftara found in MS Ginsburg Moscow of the Machzor Vitry,[15] Etz Chaim,[16] and in 12 of the 16 Ashkenazi chumashim in manuscripts I checked. Outside of Ashkenaz this was the practice among the Romaniots. It is also found in the “Zulas” piyyut of Rabbi Shmuel Hashlishi,[17] who lived in Eretz Yisrael in the 10-11 centuries and belonged to a community that read the Torah according to the annual cycle (although the Haftara ends there at 13:4, making it a Haftara of just seven verses!). It was also the Haftara for the sedra of “Vayetze Yaakov” in the triennial cycle of Eretz Yisrael.[18]

The secondary practice in Ashkenaz, which I found in three chumashim in manuscript, was to read starting from 11:7. One manuscript has the Haftara ending at 12:14,[19] and the other two end at 13:5.[20] The latter is the practice of the Ashkenazi community of Amsterdam.[21]

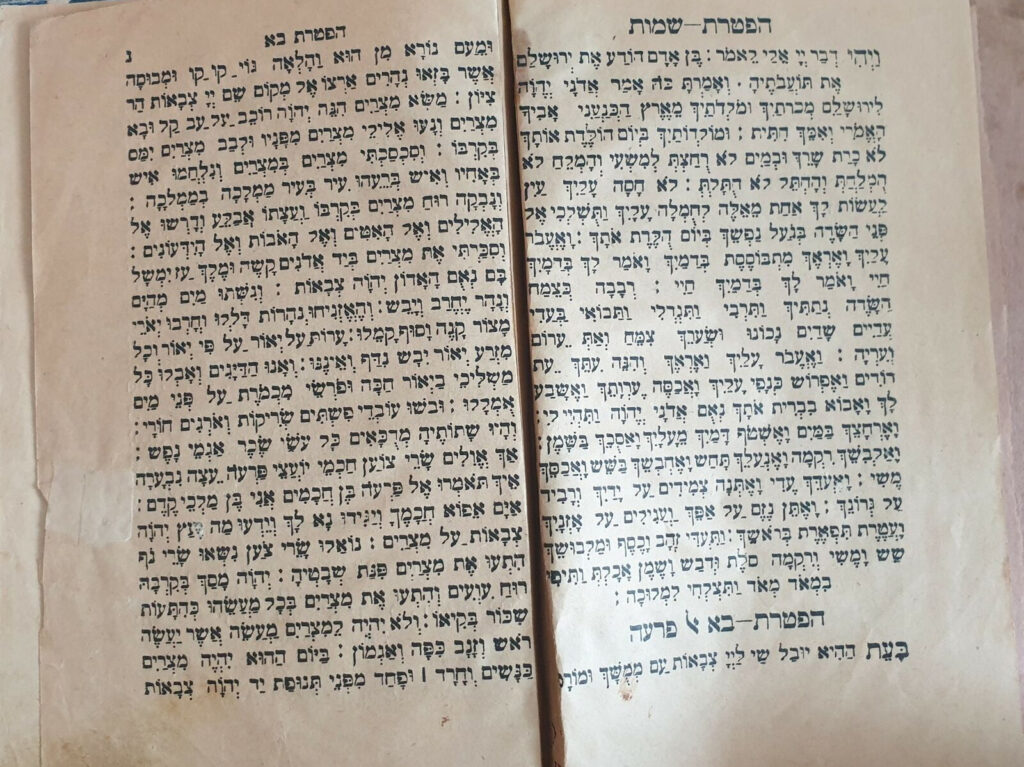

The first printed chumash with Ashkenazi Haftaros was the Soncino, printed in Brescia in 1492. It had the Haftara beginning at 12:13, following most other Ashkenazi sources. The 1517 Bomberg chumash, printed in Venice, has printed Haftaros according to both the Ashkenazi and Sephardi practices, and has the Haftara for Vayetze beginning at 11:7. After 13:5, the word “כאן” in written, followed by something that was erased (in the microfilmed copy of the Israel National Library) followed by “ההפטרה לספרדים,” that this is where the Haftara ends according to the Sefardi practice, which is quite normative. But before 12:13, at the front of the page, the words “הפטרת וישלח לאשכנזים” appear. The Haftara of Vayishlach in that chumash is from Ovadia, without any instructions, indicating a discrepancy between the two practices. It is clear that a mistake was made here, as Hoshea 12:13 is an Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayetze, not Vayishlach.

The 1517 chumash did not sell well among Jews, likely because its editor, Felix Pratensis, was a Jewish convert to Christianity.[22] In 1524 Daniel Bomberg published another chumash, this time with Yaakov ben Chayim ibn Adoniya as his editor, and this edition was much more popular among Jews. It is essential an entirely different book, as this editor did not rely on the first edition, yet, the Haftaros were, by and large, copied from the first edition, with only minor changes. Concerning our topic, the Haftara for Vayetze is 11:7, without any indication that there are other practices. Right before 12:13 it is written “כאן מתחילין הפטרת וישלח האשכנזים” with no indication where Sephardim finish the Haftara. Here too, Ovadia is listed as the Haftara for Vayishlach, without any instructions indicating that there is a discrepancy between communities.

The popularity of the chumash (already called “Mikraos Gedolos”) created a situation where a new reality was created. The Ichenhausen chumash, published in 1544, merely copied the Haftaros and their instructions from the second Bomberg chumash.

By contrast, another Venetian publisher, Marco Antonio Giustiani, also in 1544, went even further, and wrote in his chumash concerning the Haftara from Ovadia as “הפטרת וישלח כמנהג בני ספרד”. The instructions in this chumash created three changes:

- It shortened the Sephardi Haftara for Vayetze and ended it at 12:12, a verse that that discusses the Israelites performing pagan sacrifices and the ramifications of this, an extremely inappropriate way to complete a Haftara.

- It ignored the widespread Ashkenazi practice to begin the Haftara of Vayetze from 12:13. Instead, it has them all starting at 11:7 (as well as completing the Haftara at 12:12, which was unheard of).

- It created a new Ashknenazi Haftara for Vayishlach, from Hoshea, which has nothing to do with the parsha at all, and did away with the reading from Ovadia, which had been a universal practice until that time.

Not all chumashim “ruled” in such a manner. In the Lublin chumash of 1517, the original Ashkenazi Haftaros of Hoshea 12:13 for Vayetze and Ovadia for Vayishlach were listed. Likewise, the Levush, published in 1590, listed these Haftaros as well.

Soon after, we begin to see many chumashim following the new practice. For example: Manitoba – 1589, Frankfurt am Main – 1662, Venice – 1684, as well Haftara books published in Frankfurt Oder in 1685 and in 1708. Yet, I found chumashim from this period with the original Ashkenazi Haftaros, but they were both printed in Prague, which is known to have kept the original practice, as will be discussed below.

The first to point out the error of the new chumashim was Rabbi Avraham Gombiner, in his commentary, Magen Avraham, on Orach Chayim of Shulchan Aruch in siman 428:[23]

מה שכתב בחומשי’ ויברח יעקב לפ’ וישלח ט”ס הוא ושייכ’ לפ’ ויצא (לבוש)

Magen Avraham was first published in 1692, after the author’s passing. He does not explicitly mention what the Haftara for Vayishlach is, but as he cites the Levush, it is clear that he meant it is from Ovadia, as with the exception of the new practice of reading Hoshea 12:13 for Vayishlach, which the Magen Avraham clearly rejects, Ovadia was the only known Haftara for Vayishlach. Nevertheless, chumashim printed after the publication of the Magen Avraham continued to list Hoshea 12:13 as the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach.[24] Even the chumash published by R’ Shabs ai Bass, author of the Sifsei Chachamim and publisher of Magen Avraham, had this as well.

In 1718 the book “Noheg Katzon Yosef” by Rabbi Yosef Yozefa Segal was published, a work on the practices of German communities in general and Frankfurt am Main in particular. He wrote the following concerning parashas Vayetze:[25]

כתב בלבוש החור ס’ תרס”ט שהפטרה של סדר זו הוא ויברח יעקב, והפטרת וישלח הוא ועמי תלואים, עיין שם. והנה באמת במקומות שמחלקים שתי פרשיות אלו מהושע לאמרם לשתי הפטרות משתי שבתות אלו היה הדין עם הלבוש להקדים המאוחר ולאחר המוקדם. דכד נעיין ביה שפיר נראה שכתיב ויברח יעקב “ובאשה שמר” שהוא מלשון ואביו שמר את הדבר, כלומר המתין עד שתנא ראויה לביאה, או ששמר את הצאן בעד האשה, שהוא מעין פרשת ויצא. ובעמי תלואים כתיב וישר אל המלאך ויוכל , שהוא על שם הכתוב כי שרית עם אלקים ועם אנשים ותוכל הכתוב בוישלח. א”כ למה לנו ליתן את של זה בזה ושל זה בזה? ואפשר שיצא משבשתא זו מפני ששתי הפטרות אלו הם סמוכים בקרא, ועמי תלואים מוקדם במקרא, לפיכך שמו המוקדם במקרא לפרשת ויצא המוקדמת, והמאוחר לפרשת וישלח המאוחרת. והמנהג בק”ק פ”פ שמפטירין בויצא מן ועמי תלואים עד סוף הנביא, דהיינו שתי הפטרות אלו ביחד, שמספר מה אירע ליעקב. ועיין מה שכתבתי בפרשת וישלח

It is written in the Levush Hachur siman 769 that the Haftara for this seder is “Vayivrach Yaakov ,” and the Haftara for Vayishlach is “Ve’ami seluim.” In reality, places that divide the Haftara from Hoshea in order to read it as two Haftaros over two Sabbaths should follow this Levush and read the latter part first and the earlier later, as when one looks examines the matter one see it says in “Vayivrach Yaakov ” (the words) “he guarded his wife,”[26] which is similar to, “and his father kept the matter in mind,”[27] meaning [Yaakov] waited until she was fit for marriage, or it means he guarded the sheep in order to marry the woman, which is similar to parshas Vayetze. And in “Ve’ami seluim” it is written “he strove with an angel and prevailed,” which is based on the verse “for you have striven with beings divine and human and prevailed,” which is written in Vayishlach. Therefore, why should we read them in the opposite order? It is possible that this mistake occurred because these Haftaros are adjacent to each other, and “Ve’ami seluim” appears first. Therefore, they put the first Haftara for Vayetze, which is the earlier parsha, and the latter one for the later Vayishlach. But the practice in Frankfurt is to read “Ve’ami seluim” until the end of the book, meaning to read both Haftaros together.

This piece is rather difficult to comprehend.

- First, the Levush says nothing of the sort. The author proceeds to try to explain the mistake that developed due to the Levush, who did not write what is ascribed to him.

- He recommends reversing the orders of the Hoshea Haftaras, rather than recommending that Ovadia be read, which he cites later as the practice in Frankfurt.[28]

- He claims that the Frankfurt practice is to read from 11:7 until the end of Hoshea for Vayetze. All other sources claim that the practice there was to read from 12:13 for Vayetze and to read Ovadia for Vayishlach, and there is no other source for this “double Haftara” anywhere.

The Rav of Frankfurt, Rabbi Yaakov, author of the Shav Yaakov, wrote an approbation for the book “Noheg Katzon Yosef,” but after he found many errors he asked Rabbi Yehuda Miller, the author’s father-in-law, to fix the errors.[29] Some later printings of the book included these corrections in a booklet called “Tzon Nachalos,” where he wrote that the author was indeed mistaken with regard to the practice in Frankfurt.[30]

In 1729, eleven years after the publication of Noheg Katzon Yosef, Rabbi Yitzchak Aizik Mis wrote a commentary on the Haftaros known as Be’er Yitzchak, which was published in Offenbach, a town quite close to Frankfurt. He listed there various halachos and practices connected to Haftaros. He wrote there:[31]

בכל החומשים נפל טעות שציינו להפטורת ויצא ועמי תלואים ולפ’ וישלח ויברח יעקב וצריך להיות לפ’ ויצא ויברח יעקב לפי שבו כתיב ובאשה שמר שהוא מעניינא דפרשה ששמר את הצאן בעד האשה ולפ’ ושילח ועמי תלאים לפי שבו כתיב וישר אל מלאך ויוכל וגו’ שהוא מעניינא דפ’ כי שרית עם א-הים ועם אנשים ותוכל ובק”ק פרנקפורט דמיין אומרים לפ’ ויצא ועמי תלואים וגם ויברח יעקב ולפ’ וישלח חזון עובדיה

All of the chumashim have a mistake, as they cite the Haftara of Veyetze as “Ve’ami seluim” and that of Vayishlach as “Vayivrach Yaakov ,” while the Haftara for Vayetze should be “ Vayivrach Yaakov ,” as is written there “he guarded a wife” which is the matter of the parsha where (Yaakov) guarded the sheep for the wife’s sake, and that of Vayishlach should be “Ve’ami seluim,” as it is written there he strove with an angel and prevailed, which is the matter of “for you have striven with beings divine and human and prevailed.” In Frankfurt am Main they say “Ve’ami seluim” and “Vayivrach Yaakov ” for Vayetze, and “Chazon Ovadia” for Vayishlach.

It is clear that he did not just copy this out of the Noheg Katzon Yosef, as he views what is printed in chumashim as a mistake, while the Noheg Katzon Yosef mistakenly attributed it to the Levush. But it seems likely that his (erroneous) statement concerning the Frankfurtian practice does come from there.[32]

The famous printing press in Amsterdam, Proops, published a chumash in 1712 with similar Haftaros for these parshiyos to the Venice chumashim, but in another chumash, the 1734 edition, in the Haftara for Vayetze before 12:14 it is written כאן מתחילין האשכנזים פרשת ויצא while for Vayishlach, Ovadia is listed as the Haftara for Sephardim, with no mention of the Ashkenazi practice at all. It is likely that the publisher, who published a Shulchan Aruch with Magen Avraham,[33] was aware of the comment there concerning the mistake in the chumashim about the Haftara of Vayetze, but someone along the line did not realize the ramifications of this and just left Ovadia as the Haftara for Sephardim alone.

The 1754 Proops chumash cited the Venteian Haftaros, possibly as the best method to correct the error of the earlier chumash omitting an Ashekenzi Haftara for Vayishlach. But in the chumash they published in 1762, the following appears before the Haftara for Vayetze, Hoshea 11:7:

והמנהג הנכון לאשכנזים להפטרת ויצא ויברח יעקב וכן כתוב באחרונים

Before Hoshea 12:14 the following appears:

כאן מתחילים האשכנזים הפטרת וישלח, והמנהג הנכון לאשכנזי’ זהו הפטר’ ויצא ועמי תלואים שייך להפטר’ וישלח

It seems that the so-called “achraronim” mentioned here are the Be’er Yitzchak and the Noheg Katzon Yosef.

These Haftaros appear in later Proops chumashim in 1767 and 1797, as well as in another Amsterdam chumash, published in 1817 by a doctor named Yochanan Levi.

Other chumashim of the period continue to cite the Haftaros as they were listed in the Venice chumashim.[34]

Rabbi Shlomo Ashkenazi Rappaport of Chelm, in his Shulchan Atzei Shitim, wrote that the Haftara for Vayetze is Hoshea 12:14, and the Haftara for Vayishlach is from Ovadia, and in his Zer Zahav commentary he wrote:[35]

ויברח יעקב – ודלא כמו שנרשם בחומשים בטעות ויברח יעקב לפרשת וישלח דשייך לפ’ ויצא (ס’ תכ”ח)

This is clearly based on Magen Avraham.[36] It seems that his opinion concerning the Hafatros was not accepted in his day.[37]

Eighteenth-century Amsterdam was major center of Hebrew printing, and Proops was quite famous in terms of print quality, and in particular for using new methods for marketing their books.[38] Books from there were shipped to Danzig, from where they made their way into Eastern Europe. [39] Proops’ books were very popular there, which enabled them to raise the necessary funds to print a new edition of the Talmud Bavli[40] Rabbi Avraham Danziger, having grown up in the city, would have likely been exposed to the many sefarim published by Proops, and it is likely that he had their chumashim. The first edition of his Chayei Adam was published anonymously in 1810, and the matter of these Haftaros is not raised there, but in the second edition, published in the author’s lifetime in 1819, is it written:

מה שכ’ בחמשים הפטרת וישלח ויברח יעקב הוא טעות אלא בויצא מפטירין מן ויברח עד ויכשלו בם ובוישלח מפטירין מן ועמי תלואים וגם מקצת ויברח יעקב עד ומושיע אין בלתי (תכ”ח):

What was the source for this statement of the Chayei Adam? It does not seem likely that it is Noheg Katson Yosef, as that book had been published only once, a century earlier.[41] It is also not likely to be the Be’er Yitzchok, which was published in faraway Offenbach. It seems reasonable that he was exposed both to the Proops chumashim (or others with those Haftaros), as well as other chumashim with the Venetian Haftaros, which he saw as mistaken, and when he referred to “what is written in the chumashim,” he did not mean all of them.

The publishers of this of this edition, Menachem Mann and Zimmel, published a chumash for Ashkenazim in 1820 with Hoshea 14:12 as the Haftara for Vayetze and 11:7 for Vayishlach, likely following what was the ruling of the Chayei Adam at the time.

The next edition of the Chayei Adam was published in 1825, several years after the author’s death. As it had the same publisher, it seems unlikely that any changes were made by anyone but him. It is written there:

מה שכ’ בחומשים הפטרת וישלח ויברח יעקב הוא טעות אלא בויצא מפטירין מן ויברח עד סוף הושע (ואח”כ פסוקים מיואל ואכלתם אכול וכו’ וידעתם וכו’ ג”כ מטעם לסיים בטוב( ובוישלח מפטירין מן ועמי תלואים וגם מקצת ויברח יעקב עד ומושיע אין בלתי ועפ”י הגר”א נוהגין להפטיר בפ’ וישלח וישלח חזון עובדי’ (תכ”ח)

We see two changes here.

- That two verses from Yoel should be added in to the Haftara for Vayetze (which he already pointed out in the previous edition is Hoshea 12:14) which otherwise ends with the mention of sinners stumbling.[42] Evidently, earlier authorities did not think it necessary to avoid such an ending. This is cited by the Mishna Berura,[43] but is not written in any chumashim published before the Holocaust.

- He mentions that the Vilna Gaon ruled that we read Ovadia as the Haftara for Vayishlach, and those who follow him do so. The author of the Chayei Adam was related to the Vilna Gaon by marriage, and prayed with him in the Vilna Gaon’s Kloyz.

These additions were printed in later editions of the book.[44]

During the same year, 1819, Rabbi Efraim Margolies published the Sha’arei Efraim,45 which sounded similar to what was written in the Chayei Adam published in that same year:[46]

מה שנרשם במקצת חומשים הפטורת ויברח יעקב לפ’ וישלח הוא ט”ס, כי הוא שייך לפ’ ויצא, והפטורת וישלח בהושע ועמי תלואים למשובתי

It is unlikely that he saw the edition of the Chayei Adam that had been published just a few months beforehand. The fact that he writes that reading Hoshea 12:14 as the Haftara for Vayishlach is a mistake that appears in some chumashim indicates that he saw other chumashim with the Haftaros in what he considered the correct order, and is likely agreeing with them.

In the first edition of Shulchan Hakriah and Misgeres Hachulchan by R’ Dov Reifman, published in 1864, the opinion of the Sha’arei Efraim is cited,[47] but in the second edition[48] it is not.

Later, the above-mentioned publisher of the Chayei Adam, Menachem Mann, changed his name to Romm and began publishing many books in Vilna, including the famous Shas Bavli. The chumashim published there had Hoshea 14:12 as the Haftara for Vayetze, and soon other publishing houses followed suit. Romm themselves continued to follow this approach,[49] even though luchos for Vilna printed in 1826[50] and 1839[51] had Ovadia as the Haftara for Vayishlach. It seems likely that in Vilna itself the publication of the Vilna Gaon’s practice in the Chayei Adam had an immediate effect.[52] Romm published the Toras Elokim chumash in 1874,[53] continuing to list Hoshea 11:7 as the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach, yet the following note was inserted before the Haftara:

הפטרה זו וגם הפטרת ויברח יעקב היא הפטרת ויצא לספרדים מפני שהם בנביא אחד אבל האשכנזים מפטירין בויצא רק ויברח יעקב ובוישלח חזון עובדיה כמבואר ברמב”ם ובלבוש

It is not clear what it means that both Haftaros are read by Sephardim for Vayetze, and it is rather strange that Hoshea 11:7 is listed for the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach with instructions that Ashkenazim actually read from Ovadia. Before the Haftara from Ovadia the following appears:

הגם שנמצא בחומשים כתוב שהיא הפטרה רק לספרדים אך מבואר ברמב”ם ובלבוש שהיא הפטרת וישלח בין לספרדים בין לאשכנזים

These instructions appeared in the Mikraos Gedolos chumash they published in 1880, and others used these rather strange instructions as well.[54]

The Mikraos Gedolos chumash published by Kadishson in Piotrkow had the Haftara from Hoshea 11:7 without any instructions, but wrote the following before the Haftara from Ovadia:

“כ”ה דעת הלבוש וראה עוד לזה ג”כ בסי’ תרפ”ד… הפטרת שבת א’ של חנוכה …

The Levush here explains that the reason why Zecharia is the Haftara on the first Sabbath of Chanuka while the fashioning of the menoras in Melachim in read on Chanuka only in the event that there is a second Sabbath is that that a Haftara discussing the future redemption is preferred, and the editor here felt the same applies to preferring Ovadia over Hoshea for parashas Vayishlach. The same instructions appear in the Romm Mikraos Gedolos printed in 1904.

Another Romm Chumash from 1898 had Ovadia as the Haftara for Sephardim only and Hoshea 11:7 for Ashkenazim. This chumash was reprinted in 1938, but that chumash was just a copy of one that was printed in Zhitomer in 1867, which is to this day viewed as the standard “shul chumash.”

The Chayei Adam as printed in 1825 edition onward is cited by the Mishna Berura.[55] It seems that by then many communities were reading Ovadia for Vayishlach.

The practice of returning to the original Ashkenazi Haftara was not limited to Vilna and its environs. Shortly after the publication of Sha’arei Efraim, we find many communities in what became the Austro-Hungarian empire (where Rabbi Efraim was from) who read Ovadia for Vayishlach. This includes Vienna,[56] Tarnow,[57] Pressburg[58] Erlau,[59] and Eperjes.[60] But the practice in Gálszécs[61] was to read Hoshea 11:7 for Vayishlach. This was the practice in Warsaw in Russian Poland as well, according to the luach from there in 1889. By contrast, in Przeworsk[62] they still maintained the Haftaros, based on the Venice chumashim, Hoshea 11:7 for Vayetze and 12:13 for Vayishlach.

Cities that retained the original Ashkenazi practice throughout

It is impossible to know the effect of printed chumashim in various eras on every local practice, but it is clear that there were communities that simply ignored them and continued the old practice from before the era of printing. We have already seen that that was the case in Frankfurt. This was the practice in Worms as well, as seen in “Minhagei K”K Vermeiza” by Rabbi Yosefa Shamash, circa 1648.[63]

Concerning Mainz, in “Minhagei K”K BeSeder HaTefilla Unuschoseha” in the Sefas Emes siddur printed in 1862,[64] Hoshea 12:14 is the Haftara for Vayetze. Although this is a late source, it seems to reflect a very early practice and only Haftaros that are not universal in Ashkenaz[65] are written there, which is why it does not mention the Haftara for Vayishlach, which by then was standard in Ashkenaz.

Concerning Prague (Bohemia), as mentioned earlier, chumashim there retained the original Haftaros of Hosea 13:12 for Vayetze and Ovadia for Vayishlach after they ceased to be printed as the Haftaros elsewhere. One chumash printed there 1697 does not, but it states explicitly that the Hafatros are as they are printed in Amsterdam. In Mendelsohn’s Biur, printed in 1836, the following is written:

‘מנהג פראג ויברח יעקב – והיא הפטרת וישלח כמנהג האשכנזים, ויש מתחילים אותה בהושע י”א פסוק ז

The verses between Hoshea 11:7-12:13 are printed in small letters, indicating they are generally not meant to be read by the intended audience. In a chumash printed in 1893, Ovadia and Hoshea 11:7 appear as Haftaros for Vayishlach, with these instructions before the former:

כמנהג האשכנזים רק בפראג ובמדינת בעהמען מפטירין חזון עובדיה

Before the Haftara from Ovadia the following appears:

כמנהג הספרדים פראג ומדינת בעהמען

In a chumash printed in Budapest in 1898 it is mentioned as a practice of Prague; not as one of all of Bohemia.

Just like there are different sources whether the original Haftaros were maintained in Prague alone or in all of Bohemia, there is a similar matter with regard to Frankfurt. In the chumash printed in Roedelheim in 1818 the Haftara for Vayetze is Hoshea 11:7. The note there states:

בק”ק פפד”מ ורוב אשכנז מפטירין בפ’ ויצא ויברח יעקב ואינם אומרים כלל ועמי תלואים

And for Vayishlach, where the Ashkenazi Haftara is listed as Hoshea 12:14, it is written:

כאן מתחילין האשכנזים הפטרת וישלח אבל בק”ק פפד”ם ורוב אשכנז מפטירין בפ’ וישלח חזון עובדיה דלקמן

The same appears in the 1854 chumash published there, as well as all subsequent printings, including the edition this chumash published in Basel in 1964.[66] The same notes appear in a chumash printed in Konigsberg[67] in 1851 and Vienna in 1864. A chumash printed in Furth in 1901 had Hoshea 11:7 as the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach, but mentioned that the practice in Frankfurt was to read from Ovadia.

Here there is evidence that the retaining of the original Haftaros spread beyond Frankfurt, as it was the practice in the old communities of Mainz and Worms.

Another community that appeared to have retained the old practice throughout is Posen, from which there is a Pinkas[68] with unique practices and carefully retained customs.

The original practice returned, as it was mentioned in sources and chumashim in the 19th century. It was in the luchos in the Austrio-Hungarian empire mentioned before and it was the practice in Chernowitz as of 1868. Later it was mentioned in the all of the luchos in Eretz Yisrael69] and in that of Ezras Torah in the United States, causing (or reflecting) that the old/new Haftaros became the standard practice for Ashkenazim.

The reacceptance of the two original Haftaros was and is not universal. The Beis Medrash Hayashan in Berlin read Hoshea 11:7 for Vayishlach until its bitter end,[70] while the practice of Kehal Adas Yisrael there was to read Ovadia.[71] The United Synagogue communities in the United Kingdom[72] (and some synagogues in some other Commonwealth countries) still read Hoshea, as it is listed as the Ashkenazi Haftara in the Hertz Chumash.[73] The Chabad[74] practice is similar to the Sephardi practice, and Amsterdam Ashkenazim read Hoshea 11:7 for Vayetze.

Adding verses from Yoel

The Chayei Adam cited this idea, which is then cited by the Mishna Berura. Two other options are mentioned in order to finish with a positive matter. One is to finish the Haftara earlier, at 14:7, and another is to add from Micha 7:18-20.[75]

Luach Eretz Yisrael of Rav Yechiel Michel Tucazinsky cites the practice of adding the two verses from Yoel. Lately, this practice has been cited by the Ezras Torah Luach in the United States.[76] Nonetheless, out of all of the chumashim that list the Haftara from Hoshea 12:13 for either Vayetze or Vayishlach, none mentioned this practice until the Koren Chumash of 1963, which cited that there are those who add the verses, and so is written in subsequent editions until today. By contrast, there are other Israeli chumashim that do not cite this practice.

The first edition of the popular English Stone Chumash, published by ArtScroll in 1993, did not cite this practice, but from the second edition onward the verses from Yoel are there, along with instructions in English that there are those who add them.

Summary

In the pre-printing era most Ashkenazi communities read Hoshea 12:14 for Vayetze and everyone read Ovadia for Vayishlach. This changed due to a mistake in the Venice chumash of 1517, after which most chumashim listed Hoshea 12:14 as the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach and Hoshea 11:7 for Vayetze. Magen Avraham noted this error, but mentioned only the correct Haftara for Vayetze, leading Noheg Katzon Yosef, Amsterdam chumashim, and after them the Chayei Adam and Sha’arei Efraim, to claim that Hoshea 11:7 is the Ashkenazi Haftara for Vayishlach. As time passed, and possibly due to the influence of the Vilna Gaon, the practice reverted to what it originally had been, to read Ovadia for the Haftara of Vayishlach.

[1] The topic of this article is the development of the Ashkenazic practices regarding these Haftaros. Any mention of other practices is just an aside. I would like to thank R’ Avraham Grossman for editing the original Hebrew and my brother R’ Yehoshua Duker for editing the English translation. I would also like to thank Dr. Gabriel Wasserman, R’ Dr. Eliezer Brodt, R’ Elli Fischer, R’ Mordechai Weintraub, my uncle Dr. Joel Fishman, and the staff of the National Library of Israel for their assistance and input.

[2] Goldshmidt Ed. Vo. 2. Krios Vahaftaros, p. 589

[3] Hilchos Krias Hatorah Ch. 4. P. 53.

[4] Keren Re’em edition, Vol. 3 29:23 (p. 29).

[5] Albeck edition, Hilchos Krias Hatorah p. 181.

[6] The Yotserot of R. Samuel the Third, Vo. 1 227-229

[7] Piyutei R Yehuda BiRabbi Binyamin (Elitzur ed.) pp. 113-114.

[8] See Fried, “Haftarot Alternativiot Befiyuttei Yanai Ush’ar Paytanim Kedumim” Sinai 2. He states one of my main claims there; i.e., that the change of the Haftara began at the onset of the printing era, but he does not mention specifics.

[9] Cambridge T-S A-S10241, B14.22, B14.88, B14.95, B15.5, B16.21, B20.2 B20.4 20.14 Cambridge Lewis-Gibson MISC 25.53.16.

[10] See list by Y. Ofer https://faculty.biu.ac.il/~ofery/papers/haftarot3.pdf

[11] T-S AS19.241, B20.2, 4,14, B14.62c, 125, B15.5

[12] T-S B15.2, B20.2, 4.

[13] T-S B16.21

[14] Pp. 107-108

[15] ibid.

[16] ibid.

[17] pp.214-215

[18] See Ofer

[19] Ms. Par. 2168.

[20] Ms. Lon Bl Add. 9408, Kennecott 3 (the last 3 verses are not vowelized),

[21] Hahogas Beis Haknesses DK”K Amsterdam, Proops ed. p. 519 , and Machon Yerushalayim ed. p. 221. It is not clear whether or not the Ashkenazim, who established their community there in 1632, adopted the practice of the Sephardim who had arrived in the city a half century earlier, or whether they had another Ashkenazi source. Concerning Ashkenazi Amsterdam practices in general, see the introduction to the Machon Yerushalayim edition pp 41-42.

[22] Concerning Pratensis and the publication of the chumash in general, see, Penkower, J. “Mahadurat HaTanach Harishona Bomberg Laor V’Reishit Beit Defuso,” Kiryat Sefer, 1983 pp. 586-604.

[23] Meginei Eretz edition, Dyhernfurth (today Brzeg Dolny), Shabtai Meshorer pub.

[24] This is the case in the chumashim published by Levy, H. in 1735, Atias J. in 1700, and Antonis A. in 1719, all in Amsterdam, as well as the di Foc. Florence, 1755.

[25] 179:2 pp. 239-240 Machon Shlomo Auman ed.,

[26] שמר in the original.

[27] שמר in the original.

[28] p. 240

[29] Concerning the errors in the book see the introduction to this edition pp. 17-19, as well as Shorshei Minhag Ashknenaz, Hamburger R.B. vol. 2, pp. 250-251.

[30] Printed in same edition of Noheg Katzon Yosef, p. 441. Besides the chumashim (discussed later on) that discuss the Frankfurt practices, similar to what is cited in the Tzon Nachalos, this practice is also mentioned in Frankfurt by Divrei Kehillos, Geiger, R SZ, p. 369, but this source is later, as it is from 1864.

[31] Halacha 16.

[32] The book has Hoshea 12:13 as its Haftara for Vayetze. He lists Hoshea 11:7 as the Haftara for Vayishlach, followed by Ovadia under the headline “יש מפטרין הפטרה זו”. In a Haftara book with Mendelssohn’s bi’ur published by Shmidt A., in Vienna in 1818, all of the halachos mentioned in the Be’er Yitzhak were quoted, with the exception of the one with regard to Vayetze-Vayishlach. It is possible that the publisher was aware of the error here and did not want to insert it. Moreover, in the luach published by Shmidt for Vienna in 1805, he listed Hoshea 12:13 as the Haftara for Vayetze and Ovadia for the Haftara of Vayishlach, and it could be that he did not want to give the impression that the dominant practice is different from what he wrote there. The guidelines from Be’er Yitzchok, with the omission of this one, were also printed in chumashim published in Feurth by Tzendarf, D. in 1801, and another in Livorno by Prizek, A. in 1809.

[33] Published in 1720.

[34] Salzbach (1802, 1820), Livorno, 1795. Paris 1809.

[35] Siman 6:6:1.

[36] Magen Avraham was added as the source in the Krauss edition of 2013.

[37] See introduction to Krauss edit. p. 6.

[38] See “Hebrew Printing” by Fuks, L. Translated from Dutch in “European Judaism” 5:2 (summer 1971).

[39] See “Hebrew Book Trade in Amsterdam” Fuks-Mansfeld R. G. in Le Magasin de l’univers: the Dutch Republic as the centre of the European book trade: papers presented at the international colloquium, held at Wassenaar, 5-7 July 1990 / edited by C. Berkvens-Stevelinck [et al.].

[40] See Fuchs ibid.

[41] See Auman edition. Intro. p. 16.

[42] This matter is discussed at length in Zera Yaakov, Zaleznik, R.S.Z. S. 138

[43] 28:22

[44] Menachem Mann and Ziml ed. Vilna, 1829, and 1839. Huffer ed. Zhovkva 1837, Wachs Jósefów, 1839. Menachem Mann and Ziml ed. Vilna, 1839. Shklover ed. Warsaw, 1840.

[45] Published in Dubno.

[46] 9:18.

[47] S. 25 at the end

[48] Berlin, 1882.

[49] This is the case in the Mendelssohn Biur they published between 1848-1853, Tikkun Soferim in 1860, and again in 1864.

[50] Publisher unknown.

[51] Published by Menachem and Simcha Zisl, sons of R’ Boruch.

[52] Later luchos from Vilna listed Ovadia as the Haftara for Vayishlach. I was unable to read what it said for Vayetze on the 1880 copy I saw. No Haftara was listed in the 1890 edition, as only Haftaros that had alternative practices were mentioned, and Hoshea 12:13 for Vayetze had become quite widespread among Ashkenazim by them, leaving no need to mention it.

[53] There was an earlier version in 1872 but I have not been able to locate it.

[54] This includes chumashim published in Vilna by Rosenkrantz in 1893 and Metz in 1913, and a chumash published in New York by the Jewish Morning Journal (דער מארגען זשורנאל) in 1914.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Luach in 1879

[57] Found in luchos printed there annually through 1887-1890, as well as in 1894 in Vienna by Sturm, D. Luchos are the source for the other practices listed here as well.

[58] Now Bratislava from 1870, 1892, 1893, and 1894. Printed in Vienna by Elinger, M.

[59] Eger in Hungarian 1889. Printed in Vienna by Engalder.

[60] Today Presov 1887. Printed in Vienna by Ster, D.

[61] Pronounced “Gossach”, the ancestral home of my wife’s family. Today it is called Sečovce. 1888. Printed in Vienna.

[62] 1888. This appears to be the last time there is a record of the Haftaros being read that resulted from the misprinting in the Venice chumashim.

[63] Machon Yerushayaim ed. Vol II. p. 195.

[64] p. 12

[65] Ashkenaz here refers to western Germany.

[66] These instructions are found in Haphtoroth / translated & explained by Mendel Hirsch, rendered into English by Isaac Levy. London, 1966. I believe this is the last time they were given.

[67] Now Kaliningrad

[68] See Pinkas Beis Hakneses DK”K Posna, Mirsky S.K. in Brocho l’Menachem: essays contributed in honor of Menachem H. Eichenstein, rabbi of the Vaad Hoeir, United Orthodox Jewish community, St. Louis, Missouri published by the Vaad Hoeir, United Orthodox Jewish community, 1956. What is written there, that the Haftara for Vayetze is “VVayivrach Yaakov” from S. 11 is clearly a mistake in the numbering.

[69] 1947 onward.

[70] Minhagei Beis Medrash Hayashan DK”k Berlin, 1937.

[71] Minhagei Beis Hakanesses D’Khal Adas Yisrael, Berlin 1938.

[72] Heard orally from Henry Ehreich of London, as well as on the website of the Muswill Hill Synagogue. https://u.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZzoTE7ZiRKq7OeCnFVtgCP2qaUuqJtpwP27

A chumash was published by Valentine in the U.K. in 1868 with an English translation that had Ovadia as the main Haftara for Vayishlach, qualifying that some communities read Hoshea 11:7.

[73] First Edition, published in 1929 in both London and New York.

[74] p. XIII, Sefer Haftaros Lifi Minhag Chabad, Kehot, New York.

[75] In “Luach Halalachos Vihamingim LChu”L Lishnas 5779 (Weingarten edition) these practices were cited from Luach Vilna. In R. Tucazinsky’s luach he recommends that those communities that read the Haftara from a scroll that has the entire text of “Trei Asar” refrain from reading from Micha, as it is a violation of the principle not to skip to somewhere when it takes more to time to roll the scroll then for a translator to complete translating the previous verse.

[76] Nothing about this appears in the luach for 1995 and this does appears in 2000 onward. I was unable to obtain the luchos in the interim. In 2005 it is written “כתוב בחיי אדם” and nothing else, most likely a printer’s error.