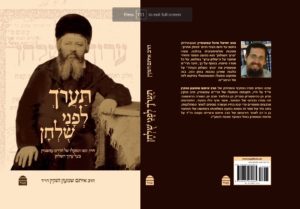

Rav

Kook’s Attitude towards Keren Hayesod – United Israel Appeal

By Rav Eitam Henkin, Hy”d

(Translated into English by Rachelle Emanuel)

This

article originally

appeared

in Hebrew in

HaMayan 51:4 (2011), pp. 75-90.

Today is the yahrzeit of the Rav Eitam and Naama Henkin, who were cruelly murdered one year ago. May Rav Eitam’s important writings, surely with us only thanks to Naama’s support, be an aliyat neshama for both. Hy”d.

·

“It is well known that the person

who heads the above [body]” supports Keren Hayesod

·

What is the difference between Keren

Kayemet Le-Yisrael – the Jewish National Fund – and Keren Hayesod — the United

Israel Appeal?

·

The forgery in the 1926 public letter

·

The significance of supporting Keren

Hayesod

·

The halakhic letter of 1928

·

The joint declaration with Rav Isser

Zalman Meltzer

·

Conclusion

“It

is well known that the person who heads the above [body]” supports Keren

Hayesod

The

philosophy of Rav Elĥanan Bunem

Wasserman, follower of the Ĥafetz

Chaim and Rosh Yeshiva of the Baranovich Yeshiva (Lithuania), and among the

most extreme of eastern European Torah leaders between the world wars in his

anti-Zionist approach, is still considered today as having significant

influence on the ideology concerning Zionism and the State of Israel prevalent

in the Hareidi community. In this respect he constitutes almost an antithesis

to the Chief Rabbi of Eretz Yisrael, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, in

whose philosophy religious Zionism found its main ideological support for its approach

and outlook.[1]

One

rare statement made by Rav Wasserman, aimed apparently at Rav Kook, has found

resonance with part of the Haredi public, and is used by them as justification

for rejecting Rav Kook and his teachings. In fact, we are not talking of a

direct reference, but of words that appear in a letter sent to Rav Yosef Tzvi

Dushinski, who took over Rav Yosef Ĥaim Zonnenfeld’s position as head of the Eidah Ĥareidit, on June

25, 1924:

A proposal has been made to combine the Ĥareidi Beit

Din with the Chief Rabbinate. It is well known that he who heads [the Chief

Rabbinate] has written and signed on a declaration calling on Jews to

contribute to Keren Hayesod. It is also known that the funds of Keren Hayesod

go towards educating intentional heretics. If that is the case, he who

encourages supporting this organization causes the public to sin on a most

terrible level. Rabbeinu Yona in

Sha’arei

Teshuva explains the verse “The

refining pot is for silver, and the furnace for gold, and a man is tried by his

praise” (Prov. 27:21) as

meaning that in order to examine a person one must look at what he praises. If

we see that he praises the wicked, we know that he is an utterly wicked person,

and it is clear that it is forbidden to associate with such a person.[2]

As

far as Rav Wasserman was concerned, because the head of the Chief Rabbinate

publicized statements in which he called to support Keren Hayesod, which among

other activities, funded a secular-Zionist education system, he was causing the

public to sin and it was forbidden to be associated with him.[3]

However,

it seems that Rav Wasserman’s sharp assertion is based on a factual error.[4]

According to Rav Kook’s son, Rav Z.Y. Kook, his father supported Keren Kayemet

Le-Yisrael, and called on others to support them, but his attitude towards Keren

Hayesod was completely different.

… as a result of the claims and complaints about

their behavior concerning religion and Judaism, [Rav Kook] later delayed giving

words of support to Keren Hayesod, and none of the entreaties and efforts of

Keren Hayesod’s activists could move him. In contrast, even though he continued

to constantly protest concerning those claims and complaints, he never

hesitated giving words of support to Keren Kayemet. None of the entreaties and

efforts of those who opposed Keren Kayemet could change this. On the contrary, with

his sacred fire, he increased his support and encouragement for Keren Kayemet, [considering

its projects as] a mitzvah of redeeming and conquering the Land.[5]

If

these words are correct, Rav Wasserman’s protest loses ground. In light of the

above we would have to say that Rav Wasserman’s sharp statement about Rav Kook

relies on the shaky basis (“It is well known…”) of rumors that were

widespread in certain localities in East Europe.[6]

However, precise research shows that despite Rav Z. Y. Kook’s clear testimony, for

which we will bring below explicit references from Rav Kook himself, Rav

Wasserman’s words were not just based on vague rumors alone. It turns out that

even while Rav Kook was alive, propaganda attempts were made to attribute to

him support for Keren Hayesod. In one case, at least, it was intentional fraud,

upon which it seems Rav Wasserman unwittingly based himself.

What

is the difference between Keren Kayemet LeYisrael – the Jewish National Fund –

and Keren Hayesod – the United Israel Appeal?

Whatever

the case may be, the reader will ask: what is the difference between the Keren

Kayemet and the Keren Hayesod? Perhaps in Rav Wasserman’s opinion they both

were “abominations,” since both organizations were headed by “heretics”;

and even though Keren Kayemet did not deal with education, nevertheless it

enabled heretics to settle on its land. If that was the case even supporting Keren

Kayemet falls into the category of lauding the wicked, etc.! However, one

cannot ignore the fact that R. Wasserman was talking about Keren Hayesod in

particular, on the grounds that its funds were “going towards raising

intentional heretics” in the educational institutions – something not

relevant to the activity of Keren Kayemet. The Keren Kayemet was a veteran

institution, founded at the beginning of the century for very specific,

accepted goals – redeeming land from the hands of gentiles, whereas Keren

Hayesod was established at the beginning of the twenties in a very different

political reality, and its fields of activity were much broader. Rav Kook

himself, in a response from winter 1925 to the famous letter from four Hasidic

rebbes (Ger, Sokolov, Ostrovtza, and Radzhin) who had heard that “your

Honor is indignant over our opposition to giving aid to the Keren Kayemet and

Keren Hayesod,” and in which they explained their opposition, gave his

reasons in full for supporting the Keren Kayemet, and only the Keren Kayemet.[7] In an

earlier draft of his response, in his handwriting, preserved in his archive, he

explicitly notes the difference in his approach to the two organizations:

I myself, in the past gave credentials for aid to

Keren Kayemet alone […] which is busy transferring land from the hands of

gentiles to Jewish possession, […] and for that I gave Keren Kayemet’s activists

a recommendation over the course of several years. This is not the case with

Keren Hayesod, which does not deal in redeeming land, but rather in settling it

and in matters of education. I have never yet given them a recommendation [and

will not do so] until the matter will, please God, be put right, and at least a

significant part of the funds will be assigned to settling Eretz Yisrael in the

way of our holy Torah.[8]

There

is indeed a large amount of information about the extensive relations that Rav

Kook had with Keren Kayemet, most of which involved continuous support for its tremendous

project of redeeming land, together with constantly keeping his eye on, and immediately objecting to, any deviation

from the way of the Torah that was perpetrated on its grounds.[9] On

the other hand, in all the writings of Rav Kook published till now, there are

only a few mentions of Keren Hayesod, and they show reservations in principle

from the organization.[10] Whoever

is fed by rumors and presents Rav Kook as one who “lends his hand to

evil-doers” without reservations, will anyway assume, “as it is

known,” that he similarly called for support of Keren Hayesod. In

contrast, for someone who knows about Rav Kook’s life story, his work, and his

letters, the idea that he would be capable of calling for support for an

organization which directly causes ĥilul Shabbat, secular education, and

so on, is utterly baseless. Even his support for Keren Kayemet was not

complete, but with conditions, restrictions, and even warnings attached. The

following are some salient examples that are sufficient to prove that if Keren

Kayemet had been involved in projects opposed to the spirit of the Torah — as

was the case with Keren Hayesod — Rav Kook would not have agreed to support it

either:

In

a letter to the chairman of Keren Kayemet, Menahem Ussishkin, from February 4,

1927, concerning violations of Shabbat in the Borokhov neighborhood located on

Keren Kayemet land (by the residents, not by Keren Kayemet itself), Rav Kook

warned them “that if they do not take the necessary steps to correct these

wrongdoings that have gone beyond all limits, I will be forced to publicize the

matter in an open letter, loud and clearly, to the whole Jewish People.”[11]

In

a letter to Tnuva from March 2, 1932, that was sent following a report

concerning

ĥilul Shabbat on Kibbutz Mizra, Rav Kook announced that so

long as the kibbutz members did not mend their ways, their milk would be

considered as

ĥalav akum (milked by a non-Jew) and Tnuva would be

forbidden from using it.[12]

In

a letter to Ussishkin from April 3, 1929, Rav Kook complained about the fact

that Keren Kayemet had started to publish literary pamphlets, “which are

not its subject matter. Money dedicated to the redemption of the Land was not

for literary purposes. Moreover, the essence of this literature damages its

image in public, spreading false views in direct opposition to the sanctity of our

pure faith […] I hope that these few words will have the correct effect, and

that the obstacle will be removed without delay, so that we will all together,

as one, be able to carry out the sacred work of redeeming the Land with the

help of Keren Kayemet Le-Yisrael.”[13]

The

forgery in the 1926 public letter

However, as has been said, because of the

significant weight that Rav Kook’s position bore, over the years many attempts

were made by the supporters of Keren Hayesod to ascribe to him outright support

of the fund. The most prominent case occurred in the winter of 1926 (about a

year after the above-mentioned letter to the hasidic rebbes). Several months

previously the yishuv in Eretz Yisrael entered a severe economic crisis which

seriously hindered its development, causing unemployment of a third of the work

force, a decrease in the number of immigrants, and a steady flow of emigrants

from the country.[14] This

crisis, considered the worst experienced by the yishuv during the

British Mandate, was the first time that the impetus of the yishuv‘s

development, which had been increasing since the end of the First World War, was

brought to a standstill. Against the backdrop of this situation, the Zionist

leadership initiated a “special aid project of Keren Hayesod for the

benefit of the unemployed in Eretz Yisrael.” Because of the severity of

the situation, Rav Kook also volunteered to encourage contributions to improve

the economic situation in Eretz Yisrael, and when R. Moshe Ostrovsky (Hameiri)

left for Poland to help with the appeal, Rav Kook gave him a general letter of

encouragement for the Jews in eastern Europe.[15] At

the same time, on November 8, 1926, Rav Kook wrote a public letter calling for

support of the Zionist leadership’s initiative, in which he wrote, inter alia:

To our dear brothers, scattered throughout the

Diaspora, whose hearts and souls yearn for the building of Zion and all its

assemblies; beloved brethren! The hard times which our beloved yishuv in

the Land of our fathers is experiencing, brings me to raise my voice with the

call, “Help us, now.” Our holy edifice, the national home for which

the heart of every Jew holds great hopes, is now facing a temporary crisis

which requires the help of brothers to their fellow sufferers in order to

endure […] Therefore I am convinced that the great declaration which the

Zionist leadership is proclaiming throughout the borders of Israel, to make

every effort to come to the aid and relief of this crisis, will be heard with

great attention; and that, besides all the frequent donations for all the

general matters of holiness which our brothers wherever they live will give for

the sake of Zion and Jerusalem, all the sacred institutions will raise their

hands for the sake of God, His people, and His Land, to give willingly to the appeal

to relieve the present crisis, until the required sum will be quickly

collected.

Although

the appeal was made through the organization of Keren Hayesod, Rav Kook avoided

mentioning the name of the fund because of his principled refusal to publicize

support for it (as he explained in the letter to the hasidic rebbes). The

version quoted above is what was published in the newspapers of Eretz Yisrael,

under the title “For the Relief of the Crisis.”[16]

However, amazingly, it becomes apparent that in the version published some

weeks later in Warsaw’s newspapers, the words “the Zionist

leadership” were changed in favor of the words “the head office of

Keren Hayesod,” and accordingly, the words were presented as nothing

less than “Rav Kook’s public letter in favor of Keren Hayesod“![17]

Even

if we didn’t have any information other than the two versions of this public

letter, there is no doubt that the authentic version is the one published by

his acquaintances, the editors of Ha-Hed and Ha-Tor in Eretz

Yisrael, close to, and seen by Rav Kook. In contrast, when members of Keren

Hayesod circulated Rav Kook’s public letter among Poland’s newspapers, they were

not concerned that the author would come across the version they had published

in a remote location. They even had a clear interest to insert into Rav Kook’s

words a precedential reference to Keren Hayesod. Even if we only had before us

the east-European version of the letter, we could determine that foreign hands

had touched it. This is not only because of Rav Kook’s words in his letter to

the hasidic rebbes sent about a year earlier, but because of a letter that Rav

Kook sent to the heads of Keren Hayesod a few weeks prior to writing the public

letter. In this letter to Keren Hayesod he informs them in brief that he is

prevented from cooperating with the management of the fund or even visiting its

offices (!) until the list of demands that he presented them with, in the field

of how they conduct religious affairs, would be met. The background to this

letter is a request sent to Rav Kook on December 7, 1926, after the

inauguration of Keren Hayesod’s new building on the site of “the national

institutions” in Jerusalem. The directors of the head office of Keren

Hayesod wrote: “It would give us great joy, and would be a great honor if

our master would be so good as to visit our office – the office of the global

management of Keren Hayesod.”[18] In

reply to this request, Rav Kook wrote a letter – which is published here for

the first time – to the heads of Keren Hayesod, (Arye) Leib Yaffe and Arthur

Menaĥem Hentke:

8th Tevet 5687 [December 13, 1926]

To the honorable sirs, Dr. Yaffe and A. Hentke,

I received your invitation to visit your esteemed

office. I hereby inform you that I will be able to cooperate for the benefit of

Keren Hayesod, and I will, bli neder, also visit Keren Hayesod’s main

office, after Keren Hayesod’s management and the Zionist leadership will

fulfill my minimal demands concerning religious issues in the kibbutzim and in

education.

Yours, with all due respect …[19]

During

the course of the years there were, nevertheless, several opportunities when

Rav Kook came into contact with members of Keren Hayesod, mainly in connection

with matters of budgets for religious needs.[20]

However, as this letter illustrates, even such limited cooperation was

dependent, from Rav Kook’s point of view, on the demand to change the way the

fund conducted its matters with respect to religion.[21] What

were Rav Kook’s exact demands of Keren Hayesod, in order for it to be

considered as having “put things right” (as he wrote in his letter to

the hasidic rebbes), and to benefit from his support and cooperation? We can

clarify this from a document which is also being published here for the first

time. This document, whose heading is “Rav Kook’s answers” to Keren

Hayesod, was apparently written after the previous letter, in reply to a

question addressed to him by Keren Hayesod concerning his attitude towards

them. It was probably written against the backdrop of rumors that Rav Kook

forbade (!) support of Keren Hayesod.[22] We only

have a copy of the document in our possession, but it is written in first

person, meaning that Rav Kook wrote it himself, and the person who copied it

apparently chose to copy just the body of the letter without the opening and

end signature:

1. I

have never expressed any prohibition, God forbid, against Keren Hayesod. On the

contrary – I am very displeased with those who do so.

2. Concerning

my attitude towards the Zionist funds: my reply was that I willingly support

Keren Kayemet at every opportunity without any reservations. However,

concerning Keren Hayesod, at the moment I am withholding my letter in its

benefit until the Zionist management corrects major shortcomings that I demand

be put right, as follows:

a.

That nowhere in Eretz Yisrael will

education be without religious instruction, not just as literature, but as the

sacred basis of Jewish faith.

b.

That all the general religious needs be

immediately taken care of in every moshav and kibbutz. For example, shoĥet,

synagogue, ritual bath, and where a rabbi is necessary – also a rabbi.

c.

That there will be no public profanation

of that which is sacred in any of the places supported by Keren Hayesod, such

as ĥilul Shabbat and ĥag in public.

d.

That the kitchens, at least the general

ones, will be particular about kashrut.

e. That

all the details here which concern the residents of Keren Hayesod’s locations,

will be listed in the contract as matters hindering use of the property by the

resident, and which will give him benefit of the land only on condition that he

fulfills these basic principles.

And because I strongly hope that the management will

finally obey these demands, I therefore am postponing my support of Keren

Hayesod until they are fulfilled. I hope that my endeavors for the benefit of

settling and building our Holy Land will then be complete.

It

should be noted that these conditions are similar in essence to those that Rav

Kook set with Keren Kayemet. However, the latter’s dealings were with redeeming

the Land, in contrast to Keren Hayesod where the areas referred to in Rav

Kook’s demands were at the center of its activity. Therefore, as far as the

Keren Kayemet was concerned, Rav Kook did not give the fulfillment of his

demands as a basic condition for his cooperation and call for support; but he

certainly did so with regard to Keren Hayesod.[23]

Whatever

the case may be, if R. Wasserman did indeed see the public letter of 1926,

without doubt he saw the falsified version published in the Polish newspapers,

and therefore he held on to the opinion that: “It is well known that he

who heads [the Chief Rabbinate] has written and signed on a declaration calling

on Jews to contribute to Keren Hayesod.”[24]

However, as has been clarified, these words have no basis.

The

significance of supporting Keren Hayesod

As

has been said Rav Kook was not prepared to support Keren Hayesod, which dealt

in education and such matters “until the matter will … be put right, and

at least a significant part” of the funds activities will be directed to

settling the Land according to the Torah. The words “at least a

significant part …” seem to give the impression that if a significant part

of the fund’s activity were directed to activity in the spirit of the Torah,

then Rav Kook would give his support even if another part were still directed

to secular education. However, in practice, there is no doubt that Rav Kook’s

demand was much stricter. In Keren Hayesod’s regulations it was determined that

only about 20% of its resources would be directed to education[25] (and

only a certain amount of that budget would be allocated to

“problematic” education) — and despite this fact Rav Kook refused to

call for its support. It must be emphasized that this policy in Keren Hayesod’s

regulations was strictly applied. An inclusive summary of the fund’s activity

between the years 1921-1930, indicates that 61.4% of its resources were

invested in aliya and settlement (aliya training, aid for refugees,

agricultural and urban settlement, housing, trade, and industry), 19.6% in

public and national services (security, health, administration), and only 19.0%

in education and culture – from which a certain part was allocated for

religious needs: education; salaries for rabbis, shoĥtim, and kashrut

supervisors; maintenance of ritual baths, eruvim, and religious

articles; aid for the settlements of Bnei Brak, Kfar Ĥasidim, etc.[26] In

light of this data, it seems that R. Wasserman’s claim against those who call

for support of Keren Hayesod, and his defining them as “utterly

wicked” people, is not essentially different from the parallel claim

against those who demand the paying of required taxes to the State – a claim

heard today only by extreme marginal groups within the Ĥaredi sector.

Indeed,

not surprisingly, it transpires that there were in fact some well-known rabbis

of that generation who did call to contribute to Keren Hayesod, despite the

problematic issues of some of its activity.[27] Just

several months before the publication of Rav Kook’s afore-mentioned public

letter, another declaration was published, explicitly calling for support of

Keren Hayesod, signed by more than eighty rabbis from Poland and Russia. Among

them were well-known personalities such as R. Ĥanokh Henikh Eigash, author of Marĥeshet;

R. Meshulam Rothe; R. Reuven Katz, and more.[28]

Moreover, in several locations, particularly in America, support of Keren

Hayesod was considered as consensus among the rabbis,[29] and

even Rav Kook’s colleague in the Chief Rabbinate, R. Ya’akov Meir, called for

support of Keren Hayesod.[30]

Would R. Wasserman have defined all of these scores of rabbis as evil ones

“who cause the public to sin on the most terrible level”?[31] Whatever

the case may be, it transpires that it was specifically Rav Kook who stands out

as being the most stringent among them, and he consistently agreed to publicize

support only for Keren Hakayemet. In the light of all the data detailed here,

one wonders whether R. Wasserman’s extreme words to R. Dushinski[32] were

only written in order to deter him from cooperating with the Chief Rabbinate

(which he strongly opposed), and perhaps this is the reason that he avoided

mentioning Rav Kook explicitly by name.[33]

The

halakhic letter of 1928

The

public letter of 1926 was indeed the only one in which Rav Kook’s words were

falsified in order to create support for Keren Hayesod. However, in the

following years, too, attempts were made to present what he had written as an

expression of direct support of Keren Hayesod. The element the two cases have

in common is that they were both published far from Rav Kook’s location. In 1928,

an announcement from the “Secretariat for Propaganda among the

Ĥaredim” was published in the Torah monthly journal Degel Yisrael,

published in New York and edited by R. Ya’akov Iskolsky. This secretariat

published a special letter from Rav Kook in Degel Yisrael, emphasizing

that the letter had not yet been publicized anywhere else. According to the

secretariat, the context in which the words were written was the following:

An

occurrence in a town in Europe, where the community demanded that all its

members contribute towards Keren Hayesod, and the opponents disputed

this before the government, and took the matter to court. The judges demanded

that the community leaders prove to them that the matter was done in accordance

to Jewish law, and on the basis of the above responsum (of Rav Kook) the

members of the community were acquitted.[34]

In

other words, according to those who publicized the Rav Kook’s letter, it was

written in order to help the heads of one European community to force all its

members to donate to Keren Hayesod. The problem is that examination of the

letter (see below) raises different conclusions. Similar to what appears above

(note 27) concerning the letter written by R. Meir Simĥa Ha-Kohen of Dvinsk,

here there is also no mention at all of Keren Hayesod. The explanations in the

letter are not relevant to the majority of Keren Hayesod’s projects, and the

letter only deals with clarifying the general virtue of settling Eretz Yisrael

and the obligation to support its inhabitants. Even the title prefacing the

letter only talks about “one community that agreed to impose a tax on its

members for the settlement and building of Eretz Yisrael,” without

mentioning that this was a tax specifically for Keren Hayesod. Towards the end

of the letter it is mentioned only that “the Zionist leadership in Eretz

Yisrael deals with many issues concerning settling the Land,” without any

specific reference to Keren Hayesod, even if the fund was the organization that

managed the appeal for the Zionist Organization. Thus, we again find that

whereas according to those that publicized the letter — the concerned parties —

the letter constitutes declared support for Keren Hayesod, in Rav Kook’s actual

words there is no mention of that.

The

letter, which as far as I know was never printed a second time, is brought here

in full:

When I was asked whether a Jewish community can impose

on an individual the obligation to give charity for maintaining the settlement

of Eretz Yisrael, I hereby reply that there is no doubt in the matter, considering

that the halakha is that one forces a person to give charity, and makes

him pawn his property for that purpose even before Shabbat, as explained in Bava

Batra 8b, and as Rambam wrote in Hilkhot Matnot Aniyim 7:10:

concerning someone who does not want to give charity, or who gives less than

what is fitting for him, the court forces him until he gives the amount they

estimated he should give, and one makes him pawn his property for charity even

before Shabbat. The same is written in Shulĥan

Arukh, Yore Dei’a, 248:1-2. If

this is the case in all charities, all the more so is it the case concerning

charity for strengthening Eretz Yisrael, for this is explicit in Sifrei, and quoted in Beit Yosef, Yore

Dei’a, §251, that the poor of Eretz Yisrael have priority over

the poor outside the Land. And because one forces a person to give charity for

the poor outside the Land, it is clearly even more the case concerning charity

for strengthening the Land and its poor. The obligation to settle in Eretz

Yisrael is very great, as it says in the Talmud Ketubot 110b, and is brought by Rambam as a halakhic

ruling in Hilkhot Melakhim 5:12: A person should always live in Eretz

Yisrael, and even in a town where the majority are idol worshippers, rather

than live outside the Land, even in a town where the majority are Jews. In Sefer Ha-Mitzvot (mitzvah 4) Nachmanides wrote: that we were

commanded to inhabit the Land; “and this is a positive mitzvah for all

generations, and every one of us is obligated,” and even during the period

of exile, as is known from the Talmud in many places.

A great Torah principle is that all Jews are responsible for one another.

Therefore, those who are unable themselves to keep the mitzvah of living in

Eretz Yisrael, are obligated to help and support those who live there, and it

will be considered as though they themselves are living in Eretz Yisrael so

long as they do not have the possibility of keeping this big mitzvah

themselves. It is therefore obvious that any Jewish community can require an

individual to give charity for the benefit of settling Eretz Yisrael and

supporting its inhabitants; and G-d forbid that an individual will separate

himself from the community. Someone who separates himself from the ways of the

community is considered one of the worst types of sinners, as Rambam writes in Hilkhot

Teshuva 3:11. Just as the community must guide the individuals towards all

things good and beneficial, and any general mitzvah, thus must it ensure that

no individual separates himself from the community concerning matters of

charity in general, and all the more so concerning matters of charity relating

to Eretz Yisrael and support of its inhabitants, as I have written. No one can

deny that which is revealed to all, that the Zionist leadership in Eretz

Yisrael deals with al lot of matters concerning settling Eretz Yisrael, hence

it is clear that its income is included in the principle of charity for Eretz

Yisrael.

And as a sign of truth and justice, I hereby sign … Avraham Yitzĥak HaKohen

Kook

The

joint declaration with Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer

Just

as the public letter of 1926 (in the version published in Poland) quickly came

to the notice of the zealots of Jerusalem, who rushed to claim that Rav Kook

supports “a baseless fund,” the same thing happened with the 1928

letter: following its publication under the above headline, the zealots rushed

to upgrade their accusations and to claim that Rav Kook ruled that one may

“force a person to give charity to Keren Hayesod” (see below).

This

fact brings us to yet another claim, raised only recently, that Rav Kook did

indeed sign on a declaration in support of Keren Hayesod. A few years ago,

Professor Menaĥem Friedman wrote about an event that occurred in winter 1930,

when the zealots of the Jerusalem faction of Agudath Israel, with Reb Amram

Blau at their head, came out with a particularly sharp street poster against

Rav Kook. The background to the attack was the joint declaration of Rav Kook,

R. Isser Zalman Meltzer, and R. Abba Yaakov Borokhov, that was published before

the convening of the 17th Zionist Congress in Basel, calling to the

attendants of the convention and its supporters to exert their influence to

prevent

ĥilul Shabbat, etc; at the side of this request, writes Prof.

Friedman, was a “call to donate to Keren Hayesod.”[35]

However,

in fact matters are not so clear at all. Prof. Friedman brings no support at

all for his words, and the only source that he brings concerning the event is

that same street poster that the zealots published. It seems that Prof.

Friedman never actually saw the said declaration, but rather assumed its

contents from the information that appears in parallel sources, such as the opposing

street poster, in which there is the claim that Rav Kook ruled that one may

“force people to give charity to Keren Hayesod,” but of course that

does not constitute an acceptable historical source.[36]

An

addition to this affair appears in a manuscript of R. Isser Zalman Meltzer,

which was published several years ago. This is a draft of a public announcement

from 1921, which shows that indeed there were those who understood that the

signature on the declaration meant support of Keren Hayesod (and other such

organizations) — but R. Meltzer clarifies that this was not the case:

Being that I signed on a call to the donors of the

Zionist funds, demanding that they do not support with their money those who

profane the Shabbat, and those who eat non-kosher food, I therefore declare

that my opinion is like it always has been: that so long as schools in Eretz

Yisrael that instill heretical ideas are supported by these funds, it is

forbidden to support them or give them aid in any way whatsoever. Those who

support and help them are destroying our holy Torah, and are ruining the yishuv.

I added my signature only to ask those who support those funds that at least

they should make every effort to influence those funds not to feed Jewish

people in kitchens that provide non-kosher food, and not to support those that

profane the Shabbat, etc.[37]

This

clarification was apparently written after reactions of amazement among some of

the Jerusalem public were voiced in the wake of the publication of the joint

declaration of R. Meltzer, Rav Kook, and R. Borokhov. From R. Meltzer’s words

it becomes clear that the joint declaration was not a call to support Keren

Hayesod, but a call to the supporters of the fund and to the attendants of the

Zionist Congress that they should anyway insist that their money should not be

used for unfitting purposes.[38]

Conclusion

Rav

Kook’s path was falsified many times, both during his lifetime and after his

death, sometimes unintentionally and sometimes intentionally. In what we have

written here, it is proven beyond all doubt that R. Elĥanan Wasserman’s claim

that Rav Kook called for the support of Keren Hayesod — a claim through which

he explained his opposition to cooperation between the Eidah Ĥareidit and the

Chief Rabbinate — is based on a mistake. The historical truth is that Rav Kook,

in his dealings with the institutions of the yishuv, more than once took

a more aggressive and stringent stand than did other rabbis of his generation,

as is expressed in the issue at hand.