Jews, Baseball, and The Yiddish Press

Jews, Baseball, and The Yiddish Press

By Eddy Portnoy

Dr. Eddy Portnoy is Senior Researcher and Director of Exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is the author of the recently-published (and much acclaimed, and fun) book, Bad Rabbi: And Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford, 2017), available here.

This is his second contribution to the Seforim Blog. His previous essay, “The Yiddish Press as a Historical Source for the Overlooked and Forgotten in the Jewish Community,” was published here.

Jews love baseball! Well, maybe not all Jews. On the one hand, the editors of the Forverts, the largest and most successful Yiddish newspaper in history, enthusiastically commissioned an article at the end of August, 1909 explaining the fundamentals of the game to their audience of Yiddish-speaking immigrants. While they may not have expected their readers to run out and play ball, they did understand that it was of value culturally to understand how the game was played. In short, it was seen as part and parcel of the Americanization process.

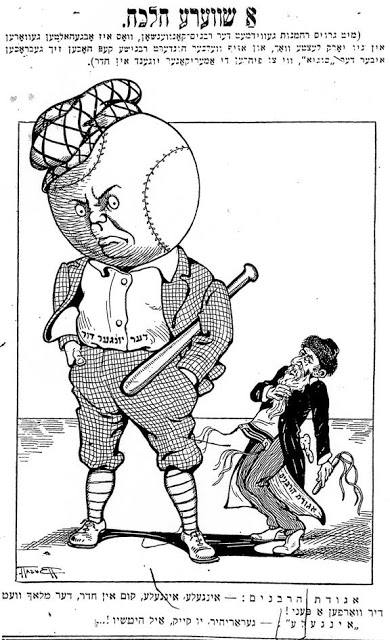

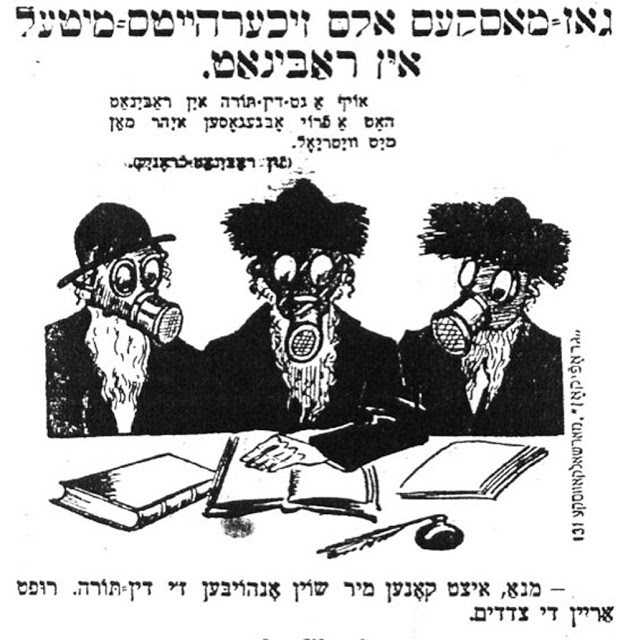

And yet, on the other hand, a cartoon that appeared a few years later reveals somewhat of an antipathy to baseball from a different Yiddish precinct. Baseball appears to have been one of those rare matters upon which both Orthodox rabbis and secular Yiddish cartoonists could agree. It is thus with great sympathy that one of the cartoonists working for Der groyser kundes views the difficulty Orthodox rabbis in America had in trying to convince American Jewish boys to attend heder. Der kundes, a very popular and very secular satire publication oriented to Left Labor Zionism, lamented the disinterest the lunkheaded, foul-mouthed, baseball-obsessed Jewish youth. Not that they necessarily supported the acquisition of a traditional Jewish education (even though all their writers had one), but they didn’t like baseball either.

Not unlike Nusakh sfard, baseball won the battle and is now a pastime enjoyed by large numbers of American Jews. Many of them even went back to heder. Left Labor Zionists satire magazines, however, aren’t doing so well anymore.

Der groyser kundes, New York, May 29, 1914

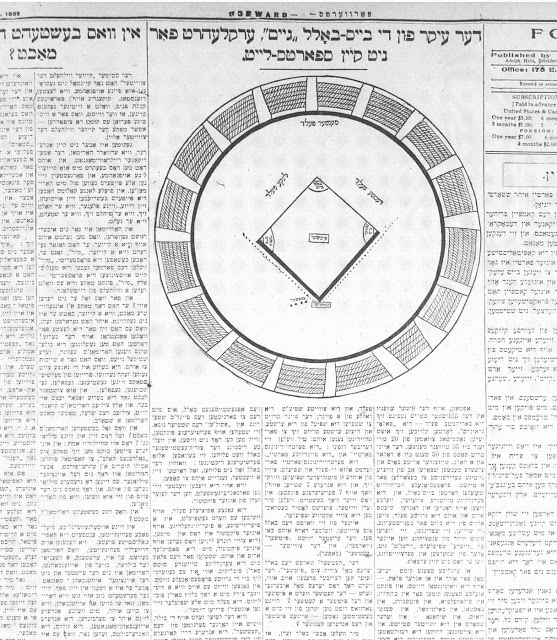

The Forverts, New York, August 27, 1909

“The

Fundamentals of the Base-Ball ‘Game’ Described for Non-Sports

Fans,” The Forverts (27 August 1909): 4, 5, translated by Eddy

Portnoy.

Uptown, on 9th Avenue and 155th Street is the famous field known as the “Polo Grounds.” Every afternoon, 20 to 35 thousand people get together there. Entrance costs from 50 cents to a dollar and a half. Thousands of poor boys and older people go without some of their usual needs in order to pay for tickets. Professional teams play baseball there and the tens of thousands of fans who sit in row after row of seats all around the stadium, go nuts with enthusiasm. They jump, they scream, they simply go wild with enthusiasm when one of “their” players does well, or, they are pained or upset when they don’t succeed.

A similar scene takes place every day in another place – in the Washington Heights. And the exact same thing goes on in Brooklyn, in Philadelphia, in Pittsburgh, in Boston, in Baltimore, in St. Louis, in Chicago – in every city in the United States. And the newspapers print the results of these games and describe what happened and tens of millions of people run to read it with gusto. They talk about it and they debate the issues.

And here we’re only talking about the “professional games:” practically every boy, nearly every youth, and not a few middle-aged men play baseball themselves, belong to baseball clubs, and are huge fans. Every college, every school, every town, nearly every “society” and every factory has it’s own baseball “team.”

Millions are made from the professional games. Related to this, there is a special kind of “political” battle between different cities. A good professional player gets eight to ten thousand dollars for one season. Some of them are educated, college-educated people.

To us immigrants, this all seems crazy, however, it’s worthwhile to understand what kind of craziness it is. If an entire people is crazy over something, it’s not too much to ask to try and understand what it means.

We will therefore explain here what baseball is. But, we won’t do it using the professional terminology used by American newspapers use to talk about the sport; we must apologize, because we’re not even able to use this kind of language. We will explain it in plain, “unprofessional” and “unscientific” Yiddish.

So what are the fundamentals of the game?

Two parties participate in the game. Each party is comprised of nine people (such a party is called a “team”). One party takes the field, and the other plays the role of an enemy; the enemy tries to block the first one and the first one tries to defend itself against them; from now on we will call them, “the defense party” and the “enemy party.”

The “defense party” also takes the field and plays. Two of the team players play constantly while the other seven stand on guard at seven different spots. What this guarding entails will be described later. Let us first consider the two active players.

One of them throws the ball to the other, who has to grab it. The first one is called the “pitcher” (thrower) and the second is called the “catcher” (grabber).

Each time, the “catcher” throws the ball back to the “pitcher.” The reader may therefore ask, if so, doesn’t it happen backwards each time – the catcher becomes a pitcher and the pitcher becomes a catcher? Why should each one be called with a specific name – one pitcher and one catcher?

We will soon see that the way in which the catcher throws the ball back is of no import. The main thing during a game is how the pitcher tries to throw the ball to the catcher.

The enemy party, however, seeks to thwart the pitcher.

This occurs in the following way:

One of the team’s nine members stands between the pitcher and the catcher (quite close to the catcher) with a thick stick (“bat”) and, as the ball flies from the pitcher’s hand, tries to hit it back with the stick before the catcher catches it.

This enemy player is called “batter.” The place where he stands is designated by a number of little stars (****).

(The other eight players on the enemy team, in the meantime, do not participate. They each wait to be “next.”)

Imagine now, that the “batter,” meaning the enemy player, finds the flying ball with his stick and flings it. If certain rules, which we will discuss later, aren’t broken, this is what can happen with the ball: if one of the “guards” catches the hit ball while it is still in the air, then the opposition of the “batter” is completely destroyed and the batter must leave his place; he is excluded (he is “out”). He puts down the “bat” and another member of his party takes his place.

The roles of the seven guards of the defense party are also specific: they must try and catch the hit ball in order to destroy the enemy’s attempt to hinder them and to get rid of the player doing the obstructing. They stand at various positions because one can never know in which direction the ball will fly. They watch the different trajectories in which the ball might fly, so a guard can be there, ready to catch it.

The readers can see the way the seven guards are distributed in our picture.

The entire official field on which the game is played is a four-sided, four-cornered one. This is in the center of our picture (The two round lines which go around it represent the tens of thousands of seats for the audience. That is how it usually is for the big professional games. It actually looks like a giant circus with a roof only for the audience. The field, with all the players, is under the open sky.).

As the readers see in the image, one corner is taken by the “catcher.” The other three corners of the four-cornered figure are stations. Each one is called a “base.” With the catcher facing the pitcher, the first “base” is outward from the direction of his right hand, just opposite him is the second base; and from his left hand is the third base.

A little bag of sand lay on every base. The guards, however, must not stand on the base, but next to it.

We previously mentioned three guards. They are called the first baseman, the second baseman and third baseman. A third guard stands between second and third base. He is called the “short stop;” when a ball is hit, it often goes in that direction and the “short stop” gets a chance to catch it in the air.

But if the ball flies way over the heads of these four “guards,” there are three other guards who stand on the outside field, or the “out field.” One of these is called the “right fielder,” the second, the “center fielder,” and the third, the “left fielder.”

Two of the four sides of the four-sided figure in our picture are marked with dots. When a hit ball flies over one of these two lines, it is called a false ball (foul ball). For it to be a proper ball (a fare ball), it must fly forward, or over the other two lines of the four-cornered figure.

When the batter doesn’t manage to hit the ball with his stick, it is called a “strike.” If he gets three “strikes,” he is “out,” or eliminated. Certain kinds of “foul balls” are considered “strikes,” however, we will not go into these details.

When the batter hits the ball and it is “proper,” and the guard doesn’t catch it, this means that the opposition, in this case, is successful. However, this success can either be greater or smaller. Depending on the level of this success, the following is done: as soon as the batter hits the ball, he throws his “bat” away and starts running; if nothing disturbs him, he runs to first base, from first to second, from second to third, and from third to the place where the catcher stands. This place is called “the home.” If he gets to the “home” spot, it means that the success of the opposition is complete.

This means that he made a whole “run:” and, based on these “runs,” the results of the game are figured out. The party which makes more runs is the winner.

But to make a full run at one time doesn’t happen all the time. In order to do so, the zetz that the batter gives the ball must be especially successful. It happens more often that he makes a quarter run, or a two quarter, or three quarter.

The rule is this: the running batter has no right to go to first base if the guard (the first baseman) holds, at that very moment, the ball in his hand. If the hit ball falls on the ground and one of the guards picks it up, the running batter is not yet eliminated. He runs. But imagine that some guard throws the ball to the first baseman and that this first baseman catches the ball before the running batter physically arrives at first base: then this runner is eliminated. But if he catches the ball when the runner is already on the base, the runner is “saved” (safe).

If the runner keeps running to second base, the rule is a bit different: the second baseman can eliminate him only if he touches him with the ball; and the same rule works for the third baseman, he has to touch him with the ball in order to get him out. The catcher or pitcher can also get a runner out with a “touch” if he finds himself near the base or the “home” to which he ran.

Each player is the embodiment of agility, with strong, swift muscles and sharp, fast eyes. And the whole game is full of “excitement” for those who are interested in it.