Woe Is Unto Whom?

Woe Is Unto Whom? Christian Censorship of a Sugya in Berachos 3a

(or What Was Bothering the Censor II)

By: David Zilberberg

I. A Censored Text in Berachos 3a

The Vilna Edition of Berachos 3a states as follows:

אמר רב יצחק בר שמואל משמי’ דרב ג’ משמרות הוי הלילה ועל כל משמר ומשמר יושב הקב”ה ושואג כארי ואומר אוי לבנים שבעונותיהם החרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין אומות העולם

The identical statement is cited by R. Yose in a Braisa that follows the above-cited section. The Braisa records the story of R. Yose’s visit to a ruin in Jerusalem to pray and his subsequent conversation with Eliyahu HaNavi upon leaving the ruin. At the end of the conversation, Eliyahu haNavi asks R. Yose whether he heard a “kol” in the ruin. R. Yose responds as follows:

ואמרתי לו שמעתי בת קול שמנהמת כיונה ואומרת אוי לבנים שבעונותיהם החרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין האומות

The meaning of the statement reported by R. Yitzchak bar Shmuel and R. Yose seems straightforward: God is expressing the magnitude of the Jewish people’s loss. And, by attributing this loss to the nation’s own sins and repeating this statement on a regular, thrice-nightly, basis, the statement serves as a constant reminder to the nation that their loss is their own fault.[1] While an element of rebuke is not explicit in the statement, it dwells right beneath the surface.

However, as noted in Dikdukei Soferim, the version of the statement appearing in the Vilna edition is incorrect. The version of the sugya that appears in all extant manuscripts (at least those available on the JNUL online repository),[2] the earliest printings of the Talmud and various Rishonim who cite it, does not include the phrase “לבנים שבעונותיהם”. Thus, in the Munich and the Firenze manuscripts and in citations to the sugya in the Menoras Hamaor (which is cited in the Dikdukei Soferim), and the Kuzari,[3] the statement reads:

אוי לי שהחרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין אומות העולם

Early Talmud printings (e.g., Soncino, Bomberg), the Rosh, Rav Hai Gaon and Rabbenu Chananel have it slightly differently:

אוי שהחרבתי את ביתי ושרפתי את היכלי והגליתים לבין אומות העולם

The Paris manuscript follows the Munich and Firenze version (“אוי לי שהחרבתי”) in the story of R. Yose and follows the Soncino version (“אוי שהחרבתי”) in the statement of Rav. Similarly, the Tosafist R’ Moshe Taku, in Kesav Tamim, cites both versions.

Either alternative has a profoundly different meaning than the Vilna version.[4] A statement casting blame at the nation for their exile becomes a statement of divine mourning or regret. Dikdukei Soferim explains the change as follows:

ובד׳ בסיליאה (של״ט) שינהו הצענזור וממנו בדפוסים האחרונים

Thus, the original text was changed in the notorious Basel edition of the Talmud at the behest of the Christian censors, and this change was retained in subsequent versions.[5]

Why was this statement censored? What did the censors find objectionable about the original version?

II. Overview of Christian Censorship of the Talmud and the Basel Edition

To answer this question, it would be useful to briefly outline the history of censorship of the Talmud by the Church. According to William Popper’s The Censorship of Hebrew Books, from the time it was first committed to writing until the High Middle Ages, the text of the Talmud survived in manuscript form relatively undisturbed by outside scrutiny. The first significant efforts against the Talmud occurred in 13th Century France. These efforts, spearheaded by Jewish apostates, culminated in the the burning of thousands of volumes of Hebrew books in the 1230s and 1240s. Similar but less extreme efforts were taken against the Talmud in Spain as well.

The Golden Age of Hebrew printing that developed in Italy in the late 15th century was abruptly ended by a “golden age” of censorship. Within years of the invention of the printing press, Italy quickly became the center of Hebrew printing. In 1483, Gershom Soncino set up a printing press, and only a year later published Masekhes Berachos. While this volume was not the first printed Talmud, it established the classic tzuras hadaf that has become synonymous with Talmud study until today. During the first half of the 16th century, other Italian printers published volumes of the Talmud, including Daniel Bomberg, who published multiple editions of the Talmud including at least one complete set. These early printed editions encountered little interference by the Christian authorities. In fact, the Bomberg edition was printed with the permission of Pope Leo X (this is not to say that the printers did not engage in self-censorship).

Starting in the end of 15th century, the Church, concerned about the ease with which the written word could now be disseminated unimpeded throughout the Christian world, began to take measures to regulate the publishing industry. The focus of these efforts was initially on books designed for Christian readers. However, as these measures became stricter, they ultimately focused on Hebrew books. In 1550, the events of 13th Century France began to replay themselves in Italy. Accusations against the Talmud by several apostates led to a renewal of anti-Talmud sentiment and ultimately to decrees directing the burning of the Talmud and prohibitions against possessing it. The Talmud benefitted from a reprieve in 1563, when the Council of Trent modified the ban against the Talmud to allow its printing as long as it was renamed (to Gemara) and the “calumnies and insults to the Christian religion” were removed. However, this limited dispensation was not exploited for many years, most likely because the risk of printing even an expurgated Talmud was deemed too great to justify the financial investment. Finally, in 1578, a printer in Basel, Switzerland decided to print a version of the Talmud that would be acceptable to the Church and hired two well known figures with solid censorship credentials — Marco Marino, the papal inquisitor of Venice, and Pierre Chevallier of Geneva — for the task.[6] The Talmud that produced in Basel was a thoroughly butchered work that was considered an utter abomination by the Jewish community. In the words of R. Rabinowitz in Ma’amar al Hadpasas Hatalmud:

ובמגינת לב ודאבון נפש ראו היהודים את התלמוד אשר הוא חיי רוחם וכל מעיינם בו נתון למרמם ביד הצענזור אשר שם בה שמות ופרעות ולזרה היה הדפוס הוה בעיניהם

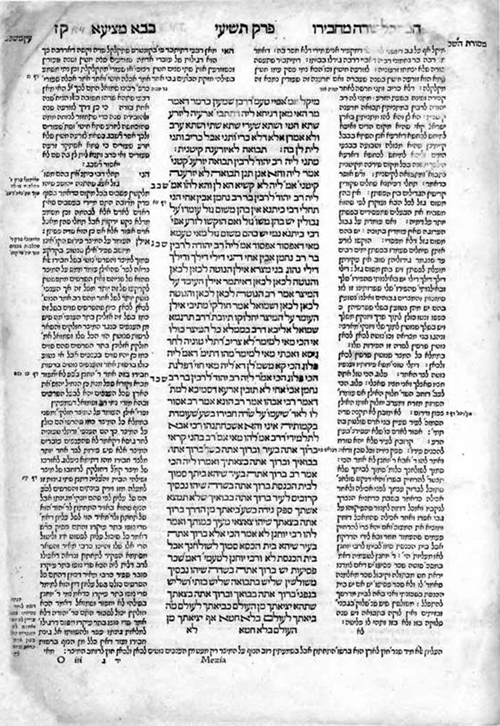

Certain words were systematically replaced, sections were removed or changed and “explanatory” notes were added. The entirety of Maseches Avodah Zara was omitted. Most shocking were the notes added to Maseches Bava Metzia. An example is the following amud:

The marginal note in the lower left hand corner is a comment on a derasha regarding the purity of a person upon entry into this world. Although difficult to read in the image posted above, Ma’amar cites the text of the note as follows:

רוצה לומר שהאדם בביאתו לעוה״ז עדיין לא חטא בעצמו ואמנם לפי אמונת הנוצרים הכל נולדים בעון אדם הראשון כדכ‘ ובחטא יחמתני אמי

There you have it – the Christian doctrine of Original Sin on a blatt Gemara.

As unconscionable as these notes are, any harm they did was short term. These changes were both clearly gratuitous and easy enough for printers to spot. Accordingly they were removed (for the most part) in later printings. The changes to the text of the Talmud itself were more pernicious because not only were they harder for printers to identify, printers of the 17th and 18th century were content with sticking with a text that passed muster rather than risking problems with the censors by reverting to the pre-Basel text.

III. Explaining the Work of the Censors

Our original questions remains: what did the censors find objectionable about our sugya?

It should be noted at the outset that it is impossible to determine definitively the reasoning of the censors. The censors left no detailed notes explaining the basis for their decisions. In addition, the censorship of the Basel Talmud, and Hebrew books more generally, was not systematic or consistent. Many have pointed out the almost comical examples of censorship revealing the utter incompetence of certain censors, who for example, indiscriminately replaced certain “buzzwords” such as “גוי” or “אדום” without regard to context. In addition, identical or near identical texts that appeared in multiple places received different treatment by the Basel censors for no apparent reason other then lack of diligence (or perhaps due to the use of two censors).[7] Thus, any attempt to divine why a particular change was made involves a bit of guesswork.

A. Anthropomorphism

Some scholars have suggested that the censors objected to the anthropomorphic nature of the original version’s portrayal of a sorrowful or regretful God, as it were.[8] However, this reason appears to be incomplete. The first Chapter of Berakhos is replete of anthropomorphic statements. God wears Tefillin, God davens and God asks for a blessing from the Kohen Gadol. All of these statements escaped the scrutiny of the censors. Anthropomorphism, it would seem, didn’t always bother them. While it might be argued that expressions of regret or sorrow by God was a form of anthropomorphism more troubling to the censor then other “garden variety” forms of anthropomorphism, I find this reasoning unsatisfactory.[9]

B. Supersessionsism

A hint at what I believe is the true reason for the change in our text is found in a book called Sefer HaZikuk. This book was printed in different versions at various times but its purpose was the same: to provide the censors with Hebrew language guidance (which, because the censors were apostates, for the most part, was the only language they could read) as to what kind of passages were considered contrary to Church doctrine.

A. M. Haberman quotes a number of the guidelines printed in one of the versions of the book.[10] Among these guidelines is:

כל מקום שאומר, שהקב”ה מצטער על אבדן של ישראל, ימחק לגמרי

The censored passage in Berachos 3a fits this guideline precisely.

Note that this book was not used by the censors of the Basel Talmud – it was written after the printing of the Basel Talmud. However, Haberman states that this book was based on the censorship standards used for the Basel Talmud. Accordingly, it provides a strong hint as to the kind of concern this passage likely raised with the Church and why it was changed.

While the Sefer Hazikuk doesn’t answer our original question, it certainly points us in the right direction. Why would an expression of divine “pain” over the Churban be objectionable? The answer would appear to be supersessionism. Supersessionism is (or at least was) a central tenet of Church doctrine. It aims to explain the status of various Divine promises to and covenants with the Jewish people contained in Tanach in light of the New Testament. The basic idea is that these promises were superseded by a new covenant with the followers of the Christian faith because the Jews failed to live up to their obligations. Thus, the destruction of the Temple and the exile and persecution of the Jewish people is a fulfillment of Church teachings.

The notion of Divine lament or pain over these events is therefore a direct affront to this brand of Christian theology – if God “replaced” the Jews due to their failures with a new people and a new covenant why would he lament or feel pain over the rejection of the Jews or the destruction of the Temple that facilitated His relationship with them? Supersessionism not only explains the “offensiveness” of the original text, but the rationale for the revised text as well.[11]

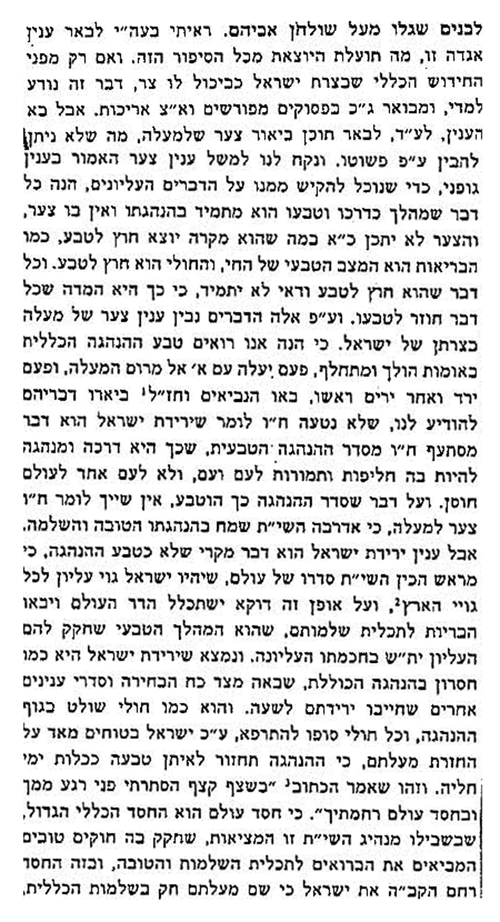

While many cases of censorship merely show the ignorance of the censor, the censorship of the passage before us should actually deepen our understanding of it. What set off alarms in the minds of Medieval Church officials should likewise signal to us that the sugya is not merely a puzzling anthropomorphic statement attributing emotions to God but, but an implicit affirmation of God’s relationship with the Jewish people.[12] In fact, this is the precisely the interpretation offered by R. Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook in his commentary on our sugya in Ayn Ayah:

III. A Note Regarding Recent Talmud Printings

It’s troubling enough that censored passages continued to be retained in nearly all printings of the Talmud over the several hundred years after the Basel Talmud. But what is completely unconscionable is that many of the “Mifuar” reprintings of the Talmud in recent years have retained these passages as well, including certain editions that boast of teams of editors exerting painstaking effort to fix the text. Most puzzling is the English Schottenstein edition of Berachos which not only retains the censored text and fails to note the correct original text, but includes a note providing a commentary on the censored text:

Accordingly, the statement “Woe to the children because of whose sins I destroyed My Temple…” may be meant to convey that since it is only because of our sins that the Temple was destroyed and our people were scattered among the nations, it is only because of our failure to repent them that the Temple continues to lie in ruins and we remain scattered among the nations. God, however, yearns for our repentance and if only we will cry out to Him in anguish and repent over our sins and return to Him, He will surely restore us to our land and rebuild the Holy Temple.

While the notion that we can extract important lessons from texts written by medieval Christian censors is somewhat peculiar, it is ironic that the explanation somehow manages to retain the hopeful message of the original uncensored text. Thankfully, the Hebrew Schottenstein edition, as well as the Oz v’Hadar and Steinsaltz editions, include the original texts in footnotes.

We are blessed to live in a society where we benefit from nearly absolute freedom of religion. All sorts of expression — even the most vile, hateful and offensive sorts – receive broad protection under law. Why do we continue to print and study editions of the Talmud marred by the fingerprints of the 16th Century Catholic Church?

Notes

[1] The statement is echoed a third time later in the sugya but with somewhat different wording. This post does not directly address this statement, although much of what is said here may apply to it.

[2] The JNUL repository shows three manuscripts of the sugya: Munich, Firenze and Paris.

[2] The JNUL repository shows three manuscripts of the sugya: Munich, Firenze and Paris.

[3] Saul Lieberman notes that this version of the text also appears in several anti-Talmud polemical texts by Christians and Karaites. Shki’in at 69-70. Lieberman demonstrates that (contra other scholars) these polemic works are valuable and trustworthy sources of Hebrew texts.

[4] More about the difference between the two alternatives below.

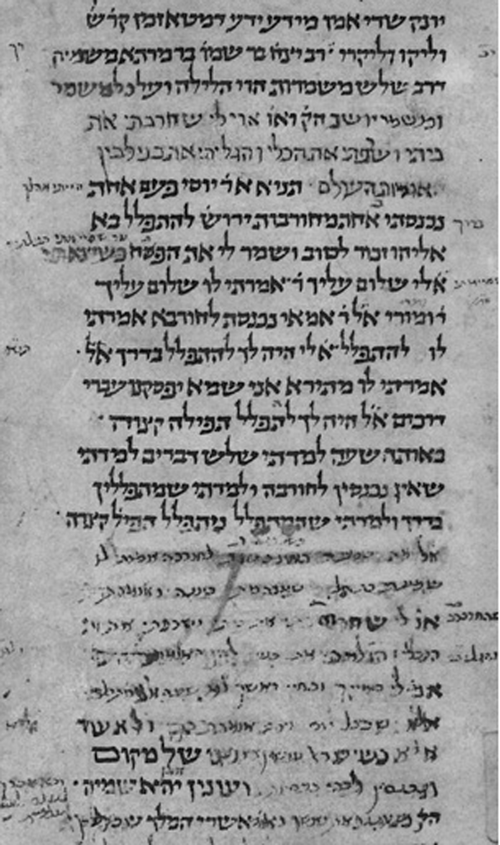

[5] Notably, the Firenze manuscript itself reflects the work of the censor. Here is the relevant portion of our sugya below.

As you can see, a censor sought to remove the text under review and a later scribe apparently sought to reinsert it. According to this, this manuscript was censored in Florence in 1472. See below for another example of the expurgation of the passage:

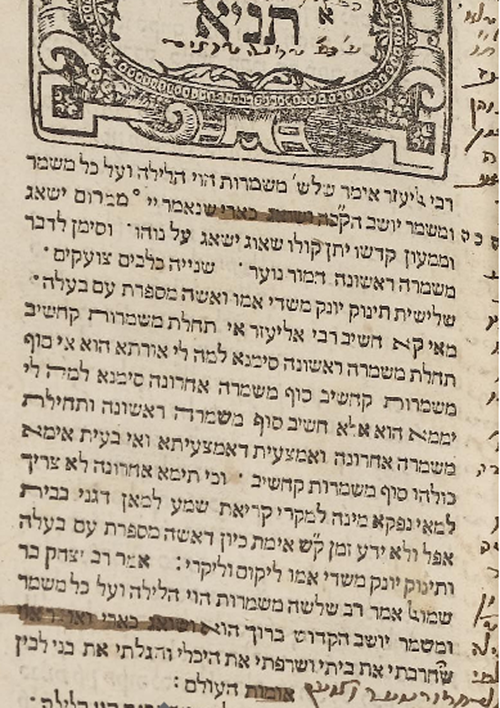

This is an image of an expurgated version of the first page of Ein Yaakov (renamed “Ein Yisrael” due to the listing of Ein Yaakov on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum) taken from the Printing the Talmud website.

[6] See Stephen G. Burnett, The Regulation of Hebrew Printing in Germany, 1555-1630: Confessional Politics and the Limits of Jewish Toleration (available here) for background regarding the printing of the Basel Talmud.

[7] Although not quite a parallel text, Chagiga 5b includes identical themes to the uncensored version of our sugya, namely, God mourning, as it were, over the persecution of the Jews and nonetheless appears in the Basel edition unscathed.

[8] Popper, Censorship at 59; Nehemia Polen, Modern Judaism, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Oct., 1987), “Divine Weeping: Rabbi Kalonymos Shapiro’s Theology of Catastrophe in the Warsaw Ghetto” at n. 18.

[9] While I am no expert on Christian censorship or Christian theology, I don’t understand why the Catholic Church would find expressions of anthropomorphism a basis for censorship. In fact, the use of the uncensored version of this passage and others like it in anti-Talmud polemical texts discussed by Lieberman would seem inconsistent with this argument. Presumably, these texts sought to ridicule and belittle the Talmud based on the anthropomorphism of the passage. Why would anthropomorphism become a reason for Christians to censor these passages a few centuries later?

[10] A. M. Habermann, The Oral Law During the Manuscript Era and the Publishing Era, available here.

[11] Credit for this insight goes to my clinical psychologist wife Penina whose prowess apparently extends to long dead church officials.

[12] Significantly, the Rosh and Rabenu Chananel, both of whom had the version of the sugya without the word “לי”, interpret the expression of woe as applying to the wicked (i.e., that due to the their misdeeds, God is compelled, as it were, to punish the Jewish nation) rather than God Himself. This less radically anthropomorphic interpretation brings the original version of the text (at least the version that the Rosh and the Rabenu Chananel had) closer in line to the Basel text. One can speculate that this line of interpretation provided a rabbinic basis for retaining the Basel text. However, this understanding cannot explain the version of the sugya in the extant manuscripts, which employ the word “לי”, thereby clearly attributing the expression of woe to God Himself.

It should be noted that Lieberman asserts that the “correct” version of the text includes“לי” based on the prevalence of this version in the manuscripts and in anti-Talmud polemical tracts. He speculates that the removal of the word “לי” is an example of Jewish self-censorship resulting from discomfort with the radical anthropomorphism of the original text. Shki’in at 70.