A Farewell to Eitam Henkin

by David Assaf

Professor David Assaf is the Sir Isaac Wolfson Chair of Jewish Studies, the Chair of the Department of Jewish History, and the Director of the Institute for the History of Polish Jewry and Israel-Poland Relations, at Tel-Aviv University.

A Hebrew version of this essay appeared at the Oneg Shabbat blog (6 October 2015) (http://onegshabbat.blogspot.co.il/2015/10/blog-post.html), and was translated by Daniel Tabak of New York, with permission of Professor David Assaf.

This is his first contribution to the Seforim blog.

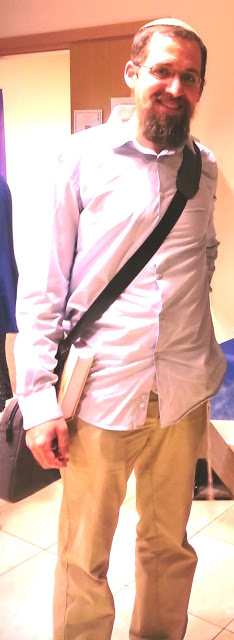

Eitam Henkin (1984-2015), who was cruelly murdered with his wife Na’ama on the third day of Hol Ha-Mo‘ed Sukkot (1 October 2015), was my student.

Anyone who has read news about him in print media or on websites, which refer to him with the title “Rabbi,” may have gotten the impression that Eitam Henkin was just another rabbi, filling some rabbinic post or teaching Talmud in a kollel. While it is true that Eitam received ordination from the Chief Rabbinate, he did not at all view himself as a “rabbi,” and serving in a rabbinic post or supporting himself from one did not cross his mind. His studies for ordination (2007-2011) constituted a natural, intellectual outgrowth of his yeshiva studies; they formed part and parcel of a curiosity and erudition from which he was never satisfied. Eitam regarded himself first and foremost as an incipient academic scholar, who was training himself, through a deliberate but sure process of scholarly maturation, to become a social historian of the Jews of Eastern Europe. This was his greatest passion: it burned within him and moved him, and he devoted his career to it. Were it not for the evil hand that squeezed the gun’s trigger and took his young life, the world of Jewish studies undoubtedly would have had an outstanding, venerable scholar.

I spent that bitter and frenzied night outside the country.The terrible news reached me in the dead of night, hitting me hard like a sledgehammer. In my hotel room in Chernovich, Ukraine, so far from home, my thoughts wandered ceaselessly to those moments of sheer terror that Eitam and Na‘ama had to face, to the horror that unfolded before the eyes of the four children who saw their parents executed, and to the incomprehensible loss of someone with whom I had spoken just the other day and had developed plans, someone on whom I had pinned such high hopes. There was a man—look, he is no more . . .

The next day, I stood with my colleagues in Chernovich, near the house of Eliezer Steinbarg (1880-1932), a Yiddish author and poet mostly famous for his parables. In a shaky voice I read for them the fine parable about the bayonet and the needle—in the Hebrew translation of Hananiah Reichman—dedicating it to the memory of Eitam and his wife, who in those very moments were being laid to rest in Jerusalem.

The Bayonet and the Needle

A man (a Tom, a Dick, or some such epithet)

comes from the wars with a rifle and a bayonet,

and in a drawer he puts them prone,

where a thin little needle has lain alone.

“Now there’s a needle hugely made,”

the little needle ponders as it sees the blade.

“Out of iron or of tin, no doubt, it sews metal britches,

and quickly too, with Goliath stitches,

for a Gog Magog perhaps, or any big-time giant.”

But the bayonet is thoughtfully defiant.

“Hey, look! A bayonet! A little midget!

How come the town’s not all a-fidget

crowding round this tiny pup?

What a funny sight! I’ve to tease this bird!

Come, don’t be modest, pal! Is the rumor true? I heard

you’re a hot one. When you get mad the jig is up.

With one pierce, folks say, you do in seven flies!”

The needle cries, “Untruths and lies!

By the Torah’s coverlet I swear

that I pierce linen, linen only…It’s a sort of ware…”

“Ho ho,” the rifle fires off around of laughter.

“Ho ho ho! Stabs linen! It’s linen he’s after!”

“You expect me, then, to stitch through

tin?” the needle asks. “Ah, I feel if I like you

were bigger…”

“Oh, my barrel’s bursting,” roars the rifle. “My trigger—

it’s tripping! Oh me! Can’t take this sort of gaff.”

“Pardon me,” the needle says.“I meant no harm therein.

What then do you do? You don’t stitch linen, don’t stitch tin?”

“People! We stab people!” says the bayonet.

But now the needle starts to laugh,

and it may still be laughing yet.

With ha and hee and ho ho ho.

“When I pierce linen, one stitch, and then another, lo—’

I make a shirt, a sleeve, a dress, a hem.

But people you can pierce forever, what will you create from them?”

Eitam was a wunderkind. I first met him in 2007. At the time he was an avrekh meshi (by his own definition), a fine young yeshiva fellow,all of twenty-three years old. He was a student at Yeshivat Nir in Kiryat Arba, with a long list of publications in Torah journals already trailing him. He contacted me via e-mail, and after a few exchanges I invited him to meet. He came. We spoke at length, and I have cared about him ever since. From his articles and our many conversations I discerned right away that he had that certain je ne sais quoi. He had those qualities, the personality, and the capability—elusive, unquantifiable, and indefinable—of someone meant to be a historian, and a good historian at that.

I did not have to press especially hard to convince him that his place—his destiny—did not lie between the walls of the yeshiva, and that he should not squander his talents on the niceties of halakha. He needed to enroll in university and train himself professionally for what truly interested him, for what he truly loved: critical historical scholarship.

Eitam went on to register for studies at the Open University, and within three years(2009-2012), together with the completion of his studies at the yeshiva, he earned his bachelor’s degree with honors.Immediately afterwards he signed up for a master’s degree in Jewish history at Tel-Aviv University, and under my supervision completed an exemplary thesis in 2013 titled “From Hibbat Zion to Anti-Zionism: Changes in East-European Orthodoxy – Rabbi David Friedman of Karlin (1828-1915) as a Case Study.”

Eitam, hailing from a world of traditional yeshiva study that is poles apart from the academic world, slid into his university studies effortlessly. He rapidly internalized academic discourse, with its patterns of thinking and writing, and began to taste the distinct savors of that world. To take one example, in July 2014 he participated in an academic conference—his very first—for early doctoral students,both Israeli and Polish, that took place in Wrocław, Poland. There he delivered (another first) a lecture in English, and got deep satisfaction from meeting other similarly-aged scholars working on topics that overlapped with his own. I asked him quite often whether as an observant Jew he found it difficult to study at the especially open and “secular” Tel-Aviv campus. He answered in the negative, saying that he never felt any difficulty whatsoever.

I was deeply fond of him and respected him. I loved his easygoing and optimistic personality, his simple humility, the smile permanently spread across his face. I loved his positive approach to everything, and especially loved his sarcastic humor, his ability to laugh at himself, at his world, at the settlers (so far as I could sense he was very moderate and distant from political or messianic fervor), at the Orthodox world in which he lived, and at the ultra-Orthodox world that was his object of study. He was a man after my own heart, and I have the sense that the feeling was mutual. When I told him one time that I was prepared to be his adviser because I was a stickler for always having at least one doctoral student who was a religious settler, so as to avoid being criticized for being closed-minded and intolerant, he responded with a grin…

More than my affection for him, I respected him for his vast knowledge, ability to learn, persistence, thoroughness, diligence, efficiency, original and critical manner of thinking, excellent writing style, ability to learn from one and all, and generosity in sharing his knowledge with everyone. In my heart of hearts I felt satisfaction and pride at having nabbed such a student.

Immediately after finishing his master’s degree, Eitam registered for doctoral studies. 2014 was dedicated to fleshing out a topic and writing a proposal. Eitam was particularly interested in the status of the rabbinate in Jewish Lithuania at the end of the nineteenth century, and he collected a tremendously broad trove of material, sorted on note cards and his computer, on innumerable rabbis who served in many small towns. He endeavored to describe the social status of this unique class in order to get at the social types that comprised it in the towns and cities. In the end, however, for various reasons that I will not spell out here, we decided in unison to abandon the topic and search for another. I suggested that he write a critical biography of the Hafetz Hayyim , Rabbi Israel Meir Hakohen of Radin (1839-1933), the most venerated personality in the Haredi world of the twentieth century and, practically speaking, until today. (Just two weeks ago I wrote a blog post describing my own recent visit to Radin, wherein I quoted things from Eitam. Who could have imagined then what would happen a short time later?) Eitam was reticent at first. “What new things can possibly be said about the Hafetz Hayyim?” he asked skeptically, but as more time passed and he deepened his research he became convinced that it was in fact a suitable topic. As was his wont, he immersed himself in the topic and after a short time wrote a magnificent proposal. At the end of March 2015 his proposal was accepted to write a doctorate under my guidance, whose topic would be “Rabbi Israel Meir Hakohen (Hafetz Hayyim): A Biography.”

A short time later I proposed Eitam as a nominee of Tel-Aviv University for a Nathan Rotenstreich scholarship, which is the most prestigious scholarship granted today to doctoral students in Israeli universities, and, needless to say, it is competitive. Of course, as I predicted, Eitam won it. He responded to the news with characteristic restraint, but his joy could not be contained. It was obvious when I gave him the news that he was the happiest man alive.In order to receive the Rotenstreich Scholarship, students must free themselves from all other pursuits and devote themselves solely to scholarship and completion of the doctorate within three years. Eitam promised to do so, and he undoubtedly would have made good on that promise. He would have received the first payment in November 2015. Now, tragically, we have all lost out on this tremendous opportunity.

One could goon and on singing Eitam’s praises, and presumably others will yet do so. I feel satisfied by including a letter of recommendation that I wrote about him to my colleagues on the Rotenstreich Scholarship Committee. Recommenders typically tend to exaggerate in praising their nominees, but let heaven and earth be my witness that in this case I meant every single word that I wrote.

May his memory be blessed.

[1] Eliezer Shtaynbarg, The Jewish Book of Fables: Selected Works, edited, translated from the Yiddish, and with an introduction by Curt Leviant, illustrated by Dana Craft (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 20-23.

* * * *

12 Nissan 5775 – 1 April 2015

RE: Recommendation for Mr. Eitam Henkin for the Rotenstreich Scholarship (22nd Cycle)

I hereby warmly recommend, as it is customarily said, that my student Mr. Eitam Henkin be chosen as a nominee of the faculty and university for a Rotenstreich Scholarship for years 5776-5778..

Henkin, who completed his Master’s studies at Tel-Aviv University with honors, and whose proposal was just now approved as a PhD candidate, is not the usual student of our institution, and would that there were many more of his caliber. One could say that I brought him to us with my own two hands, and I have invested significant time and much energy convincing him to register for academic studies so that at the end of the day he could write his doctorate under my guidance.

Henkin is what people call a “yeshiva student,” and he has spent his adult life in national-religious Torah institutions, wherein he acquired his comprehensive Torah knowledge, assimilated analytic methodology, and even received rabbinic ordination. As a scion of a sprawling, pedigreed family of rabbis and scholars, he has also revealed within himself an indomitable inclination to diverge from the typical path of Torah and invest a serious amount of his energy in historical scholarship. Naturally, Henkin gravitates toward studies of the religious lives and worlds of rabbis, yeshiva deans, and spiritual trends among Eastern European Jews in the modern period. His enormous curiosity, creative thinking, and natural propensity for study and research with which he has been endowed, as well his impressive self-discipline and independence, assisted him in mastering broad fields of knowledge through his own abilities and without the help of experts. The scope of his knowledge of Jewish history more generally, and of the Jews of Eastern Europe more specifically, including familiarity with the scholarly literature in every language, is cause for astonishment.

What is more, Henkin has already managed to publish twenty scholarly articles (!) and even a book (To Take Root: Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and the Jewish National Fund [Jerusalem, 2012], co-authored with Rabbi Avraham Wasserman, but in practice the research and writing were wholly Eitam’s). Most of them deal with varied perspectives on the spiritual and religious lives of the Jews of Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century. It may be true that these articles were published in Torah-academic journals, which we often refer to—not always with justification—as “not peer-reviewed,” but I can attest that the articles in question are scholarly in every sense; they could undoubtedly be published in recognized academic journals. I do not know many doctoral students whose baseline is as high and impressive as that of Eitam Henkin.

Given that I see in Henkin a promising and very talented scholar, I have placed high hopes in the results of the research he has taken upon himself for his doctorate under my guidance: the writing of a critical biography on one of the most authoritative personalities—one could say without hesitation the most “iconic”—of the Haredi world of the last century, Israel Meir Hakohen of Radin, better known by his appellation (based on his famous book) “the Hafetz Hayyim.” We are speaking of a personality who lived relatively close to us in time (so there exists a relative abundance of sources), yet remains concealed under a thick cover of Orthodox hagiography. One cannot exaggerate the enormous influence of the Hafetz Hayyim on the halakhic formation, atmosphere, and lifestyle of the contemporary Haredi world, with all its factions and movements, and especially what is referred to as the “Litvish” world. Nevertheless, to this day no significant study exists that places this complex personality—with the stages of his life, his multifarious writings, communal activities, and the process of his “sanctification” after his death—against the background of his time and place from an academic, critical perspective that brings to bear various scholarly methodologies.

Henkin’s doctoral proposal was approved literally a few days ago,and I am convinced that he will embark upon the process of research and writing with intense momentum, keeping pace with the timetable expected of him for completion of the doctorate.

At this stage of his life, as he intends to dedicate all of his energy and time to academic studies, Henkin must struggle with providing for his household (he has four small children). He supports himself from part-time jobs of editing, writing, and teaching, but his heart is in scholarship and the great challenge that stands before him in writing his doctorate.

Granting Eitam Henkin the Rotenstreich Scholarship would benefit him and the Scholarship. Not only would it enable him to free himself from the yoke of those minor, annoying jobs and dedicate all his time to scholarship, but it would also demonstrate the university’s recognition of his status as an outstanding student. I try to exercise restraint and minimize usage of a description like “outstanding,”and I certainly do not bestow it upon all of my students; Henkin, however, deserves it. The scholarship would assist him, without a doubt, in realizing his scholarly capabilities through writing a most important doctorate, which would add a sorely needed and lacking layer to our knowledge of the world of Torah, the rabbinate, and Jewish life in Eastern Europe of the preceding generations. As for my part, as Eitam’s adviser I obligate myself to furnish the matching amount of the scholarship from the research budgets at my disposal.

Warm regards,

Professor David Assaf

Department of Jewish History

Head of the Institute for the History of Polish Jewry and Israel-Poland Relations

Sir Isaac Wolfson Chair of Jewish Studies

* * * *

In my archive I found a document that Eitam wrote (in Hebrew) for me in preparation for his submission for the Rotenstreich scholarship. He described himself with humility and good humor:

Scholarly “Autobiography”

by Eitam Henkin