Hadaran: Who is going down to the pit of destruction?

by Leor Jacobi

A siyum of a masechet of gemorah is truly a joyous occasion, usually the culmination of many weeks of rigorous group study; challenging, edifying, and uplifting. The centerpiece of the siyum is undoubtedly the customary recitation of the unique kaddish and special additional prayers framing the accomplishment as an integral link in the chain of dissemination of Torah – from the tannaim and amoraim whose divine words we ponder, to the great rishonim and ahronim who guide us in revealing their talmudic treasures and infusing them into the modern world.

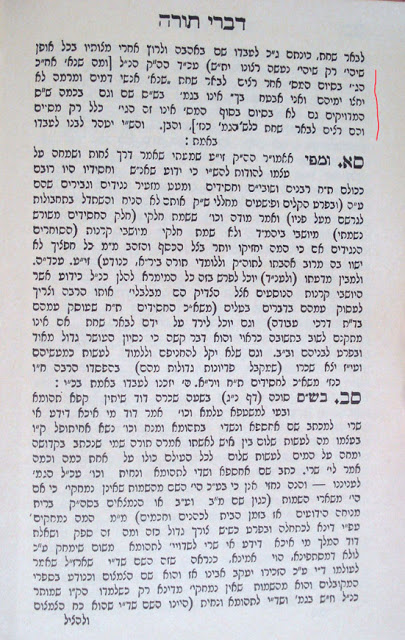

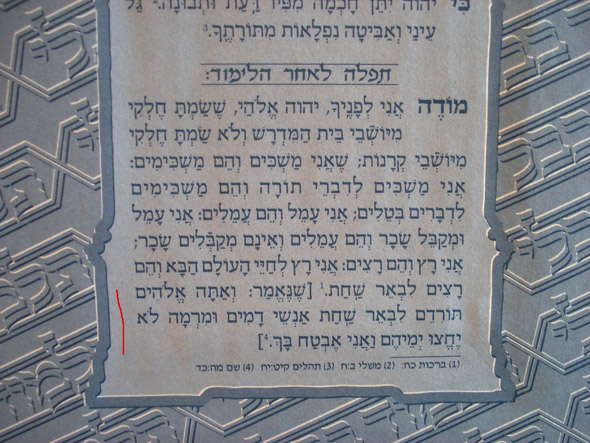

Fortunate is our lot! Our gratitude is expressed in the prayer of

Rabbi Nehunia Ben HaKana[1]:

מודים אנחנו לפניך ה’ אלהי ששמת חלקינו מיושבי בית המדרש ולא שמת חלקינו מיושבי קרנות שאנו משכימים והם משכימים אנו משכימים לדברי תורה והם משכימים לדברים בטלים אנו עמלים והם עמלים אנו עמלים ומקבלים שכר והם עמלים ואינם מקבלים שכר אנו רצים והם רצים אנו רצים לחיי העולם הבא והם רצים לבאר שחת שנאמר וְאַתָּה אֱלֹהִים תּוֹרִדֵם לִבְאֵר שַׁחַת אַנְשֵׁי דָמִים וּמִרְמָה לֹא יֶחֱצוּ יְמֵיהֶם וַאֲנִי אֶבְטַח בָּךְ

Our exalted state can only be fully appreciated when contrasted with that of those not fortunate enough to join us in the beis hamidrash. The Yoshvei Kranos, identified by Rashi as idle shopkeepers who waste their time in frivolous conversation, are deprived of the rich rewards of Torah study, both in this world and in the next. They are to be pitied and even disdained for their boorish lack of concern for lofty matters.

The prayer proceeds a step further, however, in the concluding verse from Tehillim 55:24, cursing the ignorant with early death, destruction, and perhaps even damnation! And you, HaShem, lower them into the pit of destruction, murderous swindlers, may they not live out even half their expected lifespan. Are they really so wicked? At our joyous simcha, shouldn’t we rather be resolving to help inspire and mekarev these poor folk?

Did the creator of this prayer,

Rabbi Nehunia Ben HaKana, or anyone from

Hazal recite this verse? (If so, there would certainly be a a good reason for it.) A survey of the sources reveals a resounding:

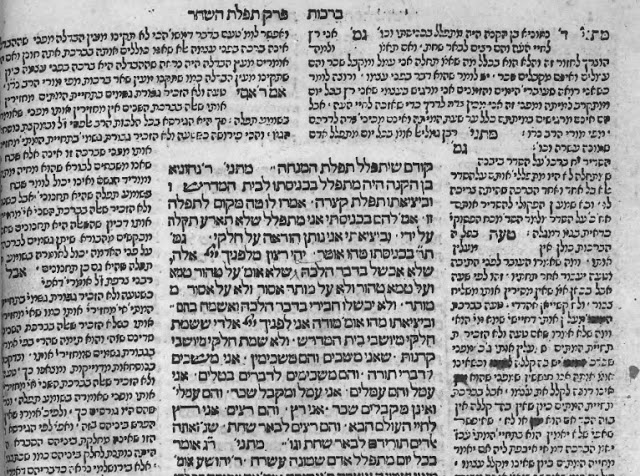

no. Not only does it not appear in Gemara Brachos 28b, but it does not appear in any of the known manuscripts,

Rambam[2], or any of the many

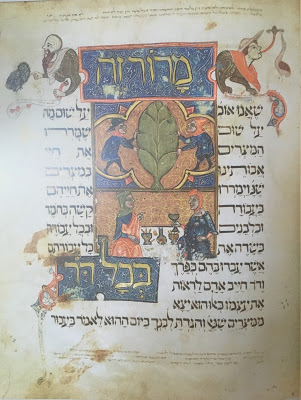

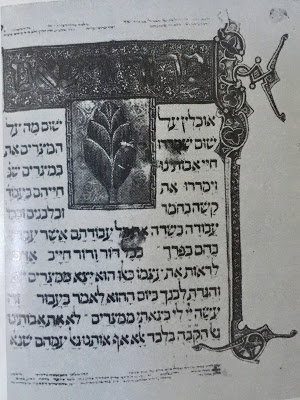

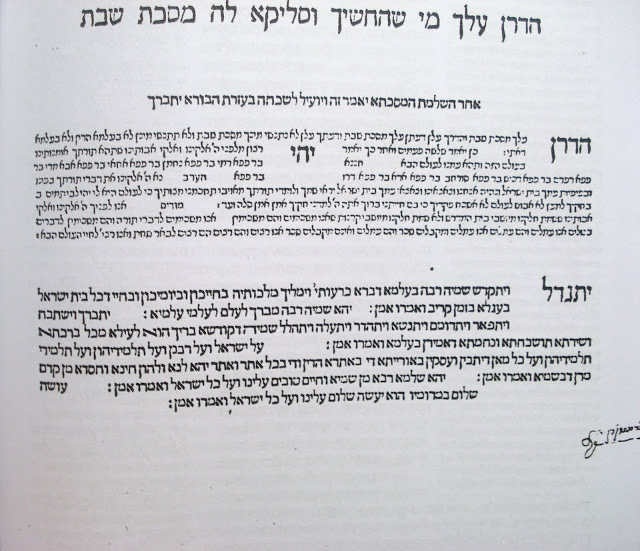

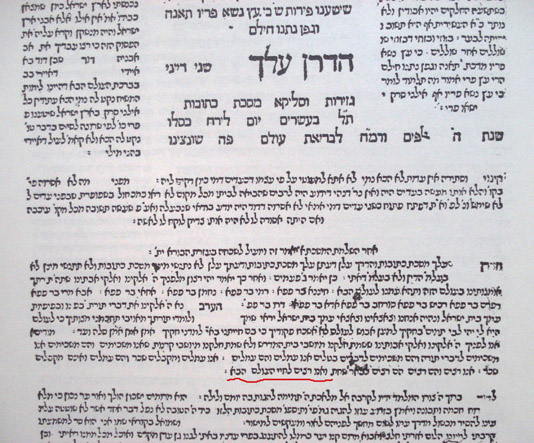

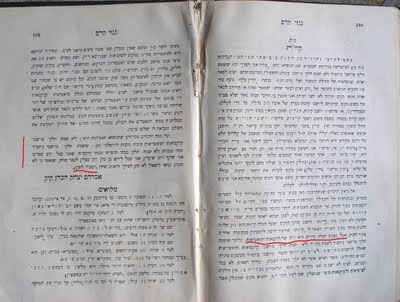

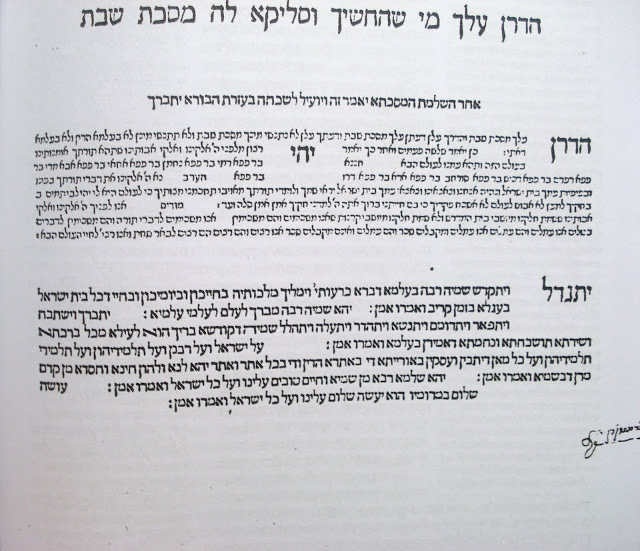

poskim rishonim that quote the prayer. Early versions of the Hadaran prayer do not include the verse either! See the attached photo of the early Venice and Soncino editions of the Talmud.

[3] Nowhere. Gornisht.

In his Sefer Divrei Torah (Mahadura 5)the Munkasczer rebbe, an avid bibliophile, indicates that the verse should be omitted.

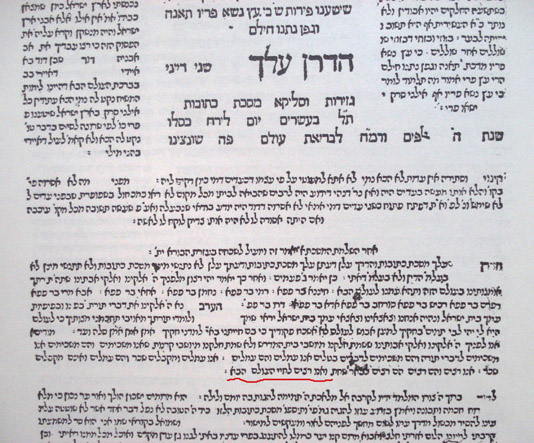

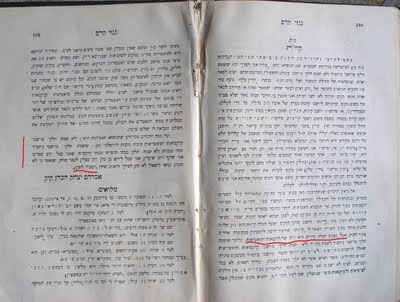

The verse only appears in one known halachic source: Halachot of Rif (Rabbi Yitzhak Alfasi). See below (1st edition, Constantinople 1509):

Why would

Rif add this verse? He is usually involved with editing away verses from the Gemorrah, not adding them! Does it reflect an ancient custom of his? Why didn’t any of the great

Rishonim who studied

Rif cite this verse?

[4] Ra’ah in his commentary on

Rif quotes the entire prayer without mentioning the verse!

None of the many known manuscript versions of

Rif mention the verse!

[5] Its earliest known appearance in this prayer is in the first printed edition of

Rif (published almost exactly 500 years ago, רס”ט, in Constantinople). Why did the publishers include the verse?

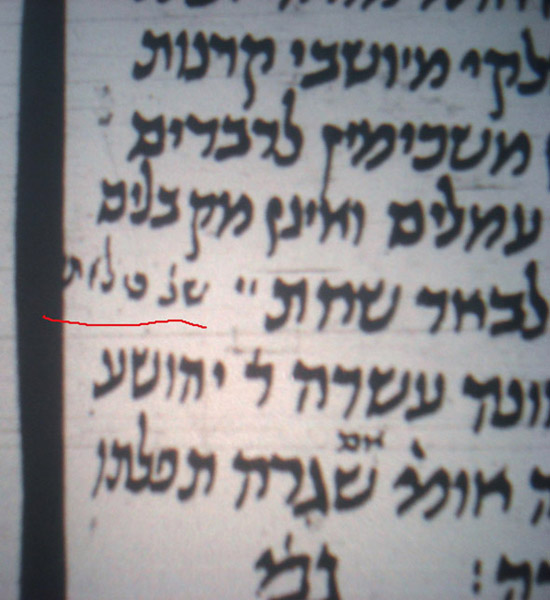

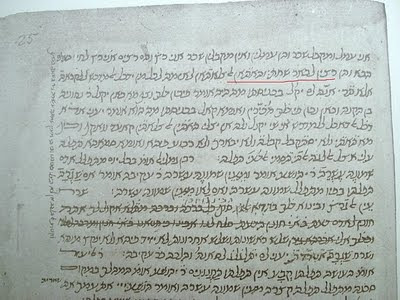

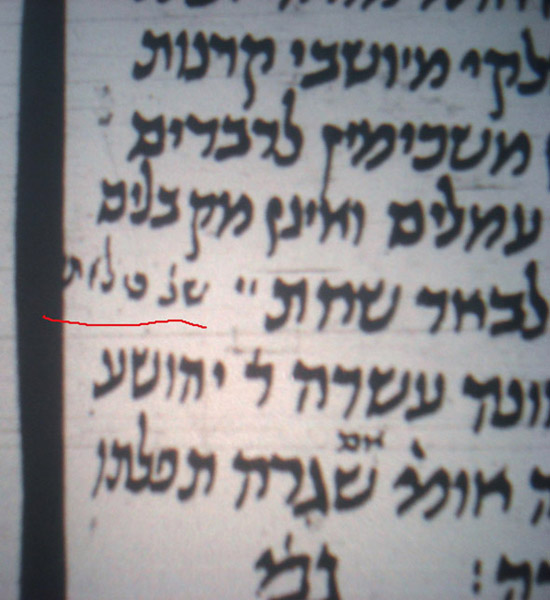

The answer may lie in a marginal gloss of one lone manuscript version of

Rif[6].

In the left hand side of the manuscript, one can see that a later scribe added a citation to a verse. Only a few letters are visible in the microfilm: שנ’ כי לא ת

This is clearly referring to a different verse! Without a doubt, it is the same verse cited at the end of the version of the prayer found in the Talmud Yerushalmi:

כִּי לֹא תַעֲזֹב נַפְשִׁי לִשְׁאוֹל לֹא תִתֵּן חֲסִידְךָ לִרְאוֹת שָׁחַת

[7]

“For you will not abandon my soul to the grave, you will not allow your pious one to see (his) destruction.”

This verse is most fitting and proper here as a conclusion of the prayer. It lacks all of the problematic vitriol of the commonly found verse. This scribal addition undoubtedly represents an ancient custom

[8], which the printers of Constantinople may have been unfamiliar with.

[9] The verse they substituted, however, was certainly most familiar to them in a different context:

משנה מסכת אבות פרק ה

אבל תלמידיו של בלעם הרשע יורשין גיהנם ויורדין לבאר שחת שנאמר (תהלים נ”ה) ואתה אלהים תורידם לבאר שחת אנשי דמים ומרמה לא יחצו ימיהם ואני אבטח בך:

The students of Bilaam are certainly deserving of such a curse, for they are involved in sorcery, treachery, and other wickedness – if only they would be idle as the shopkeepers, that would be a tremendous improvement!

The custom of reciting Pirkei Avos on Shabbos afternoon dates back to time immemorial, and as a result of the regular study, many have mastered its teachings literally by heart. It doesn’t seem at all far-fetched to assume that the printing of this verse in Rif was a simple oversight. Eventually the verse entered into the hadaran prayer as we know it.

The prayer of

Nehunia Ben HaKana is also found in many printed prayer-books in its original form, to be recited upon leaving the

Beis HaMidrash. It is usually located just after

shaharith.[10] Many of these contain the verse, such as the prayerbook printed by Rav Ya’akov Emden on his private press

[11]. But many do not contain the verse.

[12]

Rambam ruled that upon entering and exiting it is obligatory to recite the prayer of

Nehunia Ben HaKana[13]. The

Shulhan Aruch also follows his

psak. In order to further facilitate the fulfilment of this duty

, printers have

recently begun printing the prayer in the inside front covers of their

gemorrahs and

mishnayos, including the verse. The editors of

Artscroll are the most democratically accommodating – they include the verse in parenthesis. You can decide whether to say say it or not.

It’s well worth noting that a precedent to this custom of the printers is found in the Pesicha to the famous Tosafos Yom Tov commentary on the mishna by Rav Yom Tov Lipman Heller. He writes that since the recitation of these prayers is obligatory, and since many are unfamiliar with them, as they do not appear in the siddur (of his time), that he is printing them, according to the nusach of the RIF. And his nusach follows the printed version of RIF. He does not explain why he chose the RIF’s version over that of the Talmud, but it seems clear that he did not have access to manuscripts of RIF, and, unfortunately, relied on corrupted printed versions. It’s also unclear as to whether his concerns for proper nusach were with the concluding prayer at all, or with the prayer recited upon entering the House of Study, whose wording is much more varied between different manuscripts and printed versions. It could be that this “endorsement” of the Tosafos Yom Tov to the printed version of RIF contributed to the eventual inclusion of the verse in later printings of the Hadaran prayer at the end of tractates and later, in prayer-books.

Hopefully, our good friends, the “yoshvei kranos” will be taking part in a daf yomi shiur and joining us at the next siyum, reciting the Hadaran along with us, and meriting Olam HaBa!

Appendix

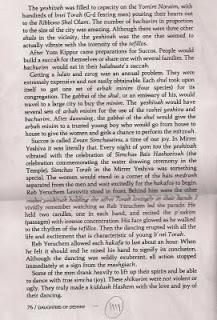

Theaters and circuses, the Talmud Yerushalmi (and Rav Kook)

(By a happy coincidence, David Segal recently

posted at the Seforim Blog on this very topic!)

We are not the first ones to find the prayer in the

hadaran to be overly contentious. No less an illuminary than Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, OBM, the first chief Rabbi of Israel, was deeply disturbed by this prayer’s tone.

Yoshvei Kranos are today’s

ba’alei batim. They keep

mitzvos and give

tsdakah. The

takanah to read the

torah on Monday and Thursday is for them, so they should not go too long without hearing words of

torah. It goes completely against the grain of Hazal to curse them! In fact, even without the verse, why should they be punished at all?

Rav Kook proposed a truly fantastic solution. A corruption occurred in the text: the yoshvei קרנות of the Talnud Bavli are really yoshvei קרו”ת, roshei teivos for קרקסיות andתרטיות , those who patron theaters and circuses, which in fact, is the exact nusach of the version of the prayer found in the baraisa of the Talmud Yerushalmi!

What exactly goes on in these theaters and circuses? The

gemarah in

Avodah Zara 18b states that they are essentially a

moshav leitzim, foolish and irreverent. Another opinion cited there is that these were much more nefarious centers of

Avodah Zara and Shfichus Damim, gladiator sports, public executions and like. Historically, both of these opinions seem correct – theaters and circuses where occasionally more pernicious activities took place. All in all, they don’t seem to be much too different than the modern versions of popular “entertainment”

[14].

The curse of Rav Nehunia’s prayer is directed against these insidious people who waste away their free time in such sordid foreign entertainments, as opposed to the

Torah-true who spend their free time immersed in learning in the

beis hamidrash or in prayer in the

beis kneses, even if during the work-day they are but simple “idle” shopkeepers. In this context, even the dubious additional verse is somewhat appropriate

[15].

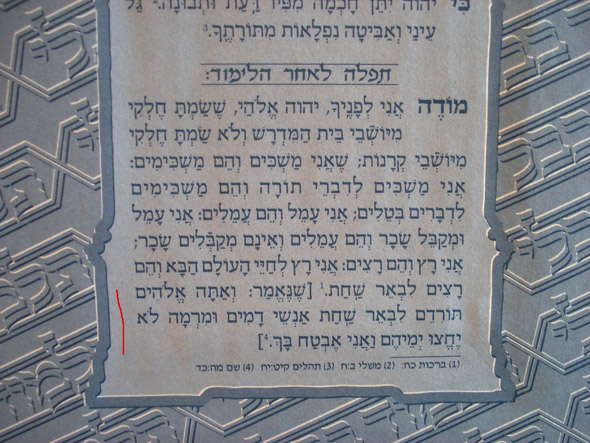

Rav Kook went so far as to call for “correcting” the nusach of the prayer and adopting the version of the

Talmud Yerushalmi! That proposition certainly has merit, but is it really the true intention of the

Talmud Bavli itself?

[16] Perhaps this is not the only suggestion of his that, in retrospect, seems a bit far-fetched.

[17] However, it seems that his insight into the tradition of the Talmud Yerushalmi and its stark opposition to “theaters and circuses” teaches a lesson which is especially pertinent today, and can deepen our appreciation of the importance of this truly enigmatic prayer.

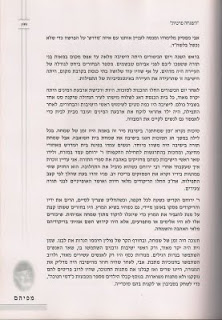

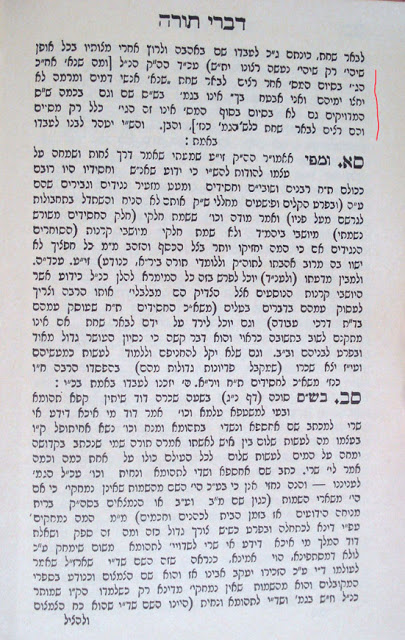

Here are Rav Kook’s words (you may click this image to read a larger copy):

The original version of the prayer appears to be found in the Talmud Yerushalmi, produced under the glare of Greco-Roman culture with its ubiquitous theaters and circuses. In Sasanian Babylon, these cultural expressions were unheard of, hence they were restated as the more familiar yoshvei kranos. In contrast, our modern secular culture of entertainment is, for the most part, a western one, and hence the version of the Talmud Yerushalmi takes on crucial added significance today.

Many thanks to Moshe Bloi, Ezra Chwat and Shamma Friedman. All errors are, of course, mine.

Note: This article is based on one which originally ran in Kolmos of Mishpacha magazine and they take no responsibility for the content here. You can read the original article

here.

UPDATE 8/18/2011: A

song has recently been composed as a result of this article and discussions surrounding it’s Hebrew and English versions. The song lyrics consist of only the two verses and highlights the contrast between them musically.

Here the composer explains the composition in Hebrew and provides a link to the previous Hebrew discussion which inspired it:

[4] In the back of the new

Oz V’Hadar gemarras, the

Magid Ta’alumos is cited, who explains that the verse is included in order to end the prayer on a positive note (!),

v’ani evtah boch, insead of

be’er shachas. The same explanation is offered by the Dinover rebbe, the the author of the classic

Bnei Yesoschar, in his

Maggid Ta’alumah (פרעמישלא תרל”ו) in his commentary

v’Heye Bracha, referring to the inclusion of the verse by the

Tosafot Yom Tov in the introduction to his monumental commentary on the

Mishna. He makes no reference to the

Rif. Perhaps he thought that the verse was added to the

Rif according to the

Tosafos Yom Tov? It’s worth noting that both the

Maggid Ta’alumos and the

Maggid Ta’alumah have the same observation on the inclusion of this verse, independently!