The Hafetz Hayyim’s Statement on Teaching Torah to Girls in Likutei Halakhot: Literary and Historical Context

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s Statement on Teaching Torah to Girls in Likutei Halakhot: Literary and Historical Context

Rachel Manekin and Charles (Bezalel) Manekin

Rachel Manekin is Associate Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland.

Charles (Bezalel) Manekin is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Maryland.

The authors live in Jerusalem, Israel.

Dedicated to the memory of our mothers, Matel Becher ע”ה and Dorothy Manekin ע”ה

R. Israel Meir ha-Kohen Kagan’s statement in his Likutei Halakhot that it is “now” a “great mitzvah” to teach Torah to girls, has attracted a great amount of attention in recent years.[1] Benjamin Brown, dating the statement to 1911, suggests that it was instrumental in the founding of the first Bait Yaakov school in 1917 by Sarah Schenirer in Kraków.[2] Haym Soloveitchik, dating the text to 1918, views it as R. Kagan’s (late) perception of the erosion of the mimetic society in the wake of World War I.[3]

We show below that the statement was published some time in תרפ”ב (last third of 1921, first two thirds of 1922), after R. Kagan, known after his book as the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, returned to Radin (Raduń), then Poland, on 25 Sivan [=July 1], 1921. The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim had spent the previous six years in Russia at a time of revolution, civil war, and the beginnings of communist policy toward Jewish religious institutions.[4] The timing of the statement on Torah education for women is significant. Several months before his arrival in Radin, a gymnasium (high school) for Orthodox girls had been established in Telz, with the direct involvement of the rosh yeshiva, R. Yosef Leib Bloch, his son, and his son-in-law.[5] Girls were taught there ḥumash and nevi’im. A primary school for girls was also established there. This was the latest in a series of Orthodox initiatives for the formal Torah education of women in Lithuania. In Kovno, a Jewish realgymnasium for Orthodox boys and girls had been established already in 1915 through the efforts of the Neo-Orthodox R. Dr. Leopold Rosenak, a brother-in-law of Emanuel Carlebach, and Joseph Carlebach, Emanuel’s brother. These initiatives were introduced as responses to the requirement of mandatory primary education, first by the German military occupying Lithuanian and later by the government of independent Lithuania. Also, in Kovno, at the initiative of Ze‘irei Yisrael, which was composed of representatives of Agudat Yisrael and the Mizrahi, the Yavne Central School System was founded in 1920; in its first year, forty schools were founded; some included girls.[6] In Kraków, then in Habsburg Galicia, Sarah Schenirer founded her afternoon supplementary school in 1917 with the blessing of the Belzer rebbe; several other schools followed in 1921 and 1922. In Warsaw, formerly in Congress Poland, R. Emmanuel Carlebach founded the Chavatzelet Orthodox women’s gymnasium in the same year, with the blessing of the Gerer rebbe. Chavatzelet taught girls ḥumash and nevi’im in the Hirschian spirit of Torah ‘im derech ’ereẓ.[7] In the 1930s the school was attended also by Hasidic girls, including the Gerer rebbe’s granddaughter.[8]

Moreover, in late January, 1922, the year in which the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s statement was published, the assembly of the Agudat ha-Rabbanim of Poland issued a series of calls upon its members that included the following:

11. To educate the daughters in the spirit of yiddishkeit and to learn with them from their early childhood some words of Torah and musar, and commensurate with their age to continue to learn with them their obligations in such a manner that when they reach the age of marriage, they will easily accept the obligations pertaining to the purity of the daughters of Israel. And the members are obliged to establish in their towns for this purpose a special school for the young women.[9]

As we shall see below, the resolution that called upon all communal rabbis in Poland to establish schools for women followed an impassioned speech on the challenges facing Torah education in Poland by the Galician rabbi, R. Meir (Maharam) Shapira, then the Rav of Galina, and shortly to become one of Agudat Yisrael’s representatives to the Polish Sejm and the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Ḥakhmei Lublin.

In light of the above, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s statement on teaching Torah to Jewish daughters should be read as a hekhsher of formal Jewish education for women after and while schools for Orthodox girls were established in Poland and especially in Lithuania. All the aforementioned schools had strong connections with Agudat Yisrael operatives in their various locales. As is well known, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim was a major rabbinical authority for the Agudah; several months after his return to Poland (which now incorporated parts of Lithuania), he and R. Ḥayyim Ozer Grodzinsky of Vilna, called for the strengthening of the Lithuanian Agudah.[10] He was most likely informed about these schools, certainly the women’s gymnasium in Telz, upon his return to Radin, if not earlier.

In any event, the 1924 decision to have Keren ha-Torah, the education fund of Agudat Yisrael, support a network of Jewish schools for girls was sanctioned by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s aforementioned statement, according to Dr. Leo Deutschländer, the head of Keren ha-Torah, and subsequently one of the administrators of the Bait Yaakov seminary in Krakow.[11]

It is important to emphasize that the educational policies of all Orthodox schools in Poland-Lithuania were subject to rabbinical authority, and that no pedagogical steps were taken without consultation with, and approval, by rabbinical leaders.[12]

Part One. The Literary Context of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s Statement on Women’s Education

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s comment does not appear as a formal response to a halakhic question of the permissibility of teaching Torah to women. Rather it appears as a footnote to the halakha that women should not be taught written Torah ab initio cited in his Likutei Halakhot on Sotah. Likutei Halakhot is a condensation of the halakhic sections of the Gemarah in the manner of R. Isaac Alfasi’s Halakhot Gedolot. Initially a project to provide students with a halakhic digest to sugyot having to do with kodeshim, the study of which the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim considered to be unduly neglected and of capital importance,[13] the project was ultimately expanded to provide a halakhic digest of all sugyot on which there was no Rif or Rosh (R. Asher b. Yehiel). Unlike the Rif, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s’s aim was not to decide the halakha, but rather to provide student with an abridged description of the development of the halakha through the Rambam.[14] The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim believed that by reading halakhic condensations of the Rif with Rashi, and Likutei Halakhot with Rashi, the students would be able to master the fundamental halakhot of the Talmud – something that he felt could not be easily accomplished by reading the Mishneh Torah with its commentaries.[15] In later years he recommended such a program of study for those who lacked the time for in-depth study of the Gemarah.[16]

Before we analyze the footnote, we need to justify dating Likutei Halakhot on Sotah to תרפ”ב. Unfortunately, determining the publication history of Likutei Halakhot is complicated. The work was published serially, beginning with Zevaḥim, in 1899/1900,[17] in the form of kuntresim, which could be bound and published as seen fit by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim; the published volumes did not carry a separate title page from the individual kuntresim comprising them. The title pages of the kuntresim often do not mention all the titles of the individual tractates contained therein, and, like many Torah publications, their dates of publication on the title page have to be derived from gematriyot of rabbinic statements in which certain letters are in bold typeface. Sometimes tractates that were published earlier were republished with the same title page. The individual tractates themselves have their own pagination. An edition of the entire work was published by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s son-in-law, R. Menaḥem Mendel Yosef Zaks, in Brooklyn in 1960, and in Jerusalem 10 years later. The edition contains, dispersed throughout the work, some of the original title pages, but not always with their original dates. The order of the tractates in the R. Zaks edition is also not always according to the order of publication; sugyot from the same tracate that appeared in different kuntresim are placed together.

As noted above, two dates for Likutei Halakhot on Sota appear in the secondary literature, 1911 and 1918. We have found no textual basis for either date. The 1911 date appears in M. Gellis’s bibliography of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s writings without explanation.[18] We do not know what is the source for the 1918 date.[19]

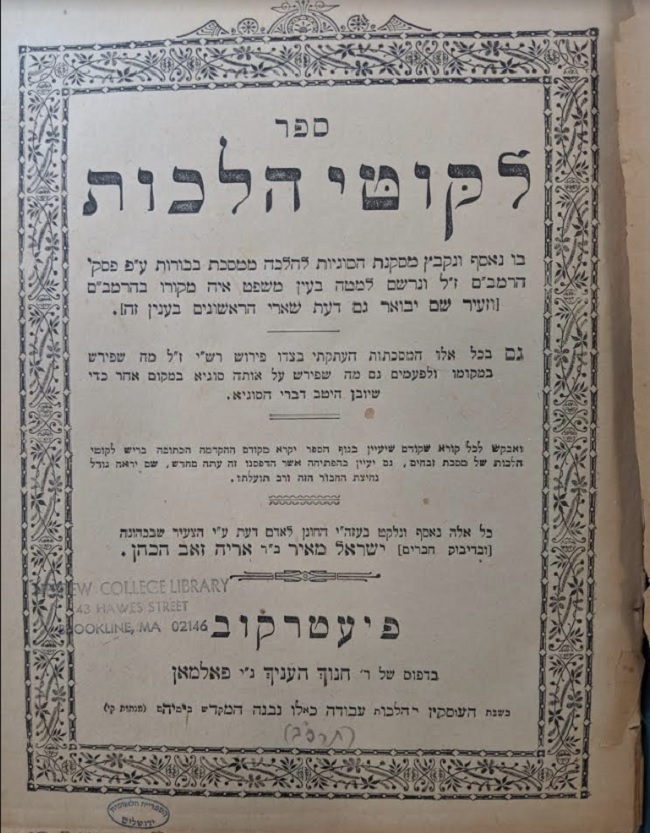

The volume of Likutei Halakhot including Sotah that we inspected in the National Library of Israel binds three kuntresim together. The first consists of Bekhorot and Keritot, printed by H. H. Fohlman, the second consists of Arakhin, Nazir, and Sotah, with only Arakhin mentioned on the title page, without a date; the third consists of Niddah, printed by M. Cederbaum, undated. Of these tractates, only Sotah and Niddah appear for the first time. (Niddah also appears published with its own title page by Cederbaum in תרפ”ג.) The date on the cover page, תרפ”ב was added in pencil, perhaps by a library cataloger or book seller, after calculating the gematriya; the volume, belonged formerly to the Boston Hebrew College library.

The תרפ”ב date is derived from the gematria of the emphasized letters: The saying (העוסקין בהלכות עבודה כאלו נבנה המקדש בימיהם (מנחות קי totals 682 ( 25 + 49 + 107 + 56 + 87+ 63 + 295), i.e., תרפ”ב.

As noted, the separate cover page for Arakhin (including Sotah and Nazir) is undated:

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, who was in charge of the printing and distribution of his books, advises on the title page of Likutei Halakhot on Bekhorot not only to read the Introductions, but also to look at the Preface (הפתיחה) “which we have now newly printed” (אשר הדפסנו זה עתה מחדש). The phrase “which we have now newly printed” is ambiguous; it can mean that the Preface is being reprinted or printed for the first time. Although the natural reading today would be the former, we found the Preface printed only in Likutei Halakhot on Sanhedrin, which we date to late תרפ”ב. And on the title page of Niddah, published by Cederbaum in תרפ”ג, we find a reference to the Preface אשר נקוה שנדפיסה בקרוב (“which we hope to print soon.”) This sort of discrepancy should not worry us, especially since Likutei Halakhot on Sanhedrin was printed by Fohlman and on Niddah by Cederbaum.

The Preface, published for the first time in תרפ”ב enables us to provide a clear terminus a quo for the publication of Likutei Halakhot on Sotah. In the middle of the first paragraph, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim lists the tractates already completed (parentheses in the text below appear originally in the kuntresim as square brackets; the square brackets here are our own):

Barukh Ha-Shem, we have collected, according to our meager opinion, the words of the Rambam that he codified from the sugyot on thirteen tractates that pertain to matters of kodeshim, namely, Zevaḥim, Menaḥot, Tamid, Pesaḥim (from Tamid ha-Nishḥat to ‘Arvei Pesaḥim), Hagigah, Yoma, Tamid, Temurah, Keritot, Bekhorot [the three final chapters), ‘Arakhim, Me‘ilah, and Nazir (the later also has many things that are relevant to kodeshim), and likewise the first two chapters of Shavuot […] and now, only a few tractates are missing from the Shas, may God grant that over time some Jews will be found to complete the entire Shas […].[20]

And in the second paragraph he writes:

I wrote all this [i.e., the Preface until the present point] more than ten years ago. We have experienced many wanderings because of the war. Barukh Ha-Shem, who has kept us alive and did not allow our feet to falter. And now that I have come from the diaspora to my home, Ha-Shem, yitborakh, has helped me in his abundant kindness and goodness for the merit of Israel to complete Likutei Halakhot on the other tractates of the Shas that do not have the commentaries of the Rif and the Rosh. (And these are: Rosh Hashanah, Makkot, Horayot, Sotah, and Niddah […]).[21]

The second paragraph of the Preface attests to a time gap in both the composition of the Preface and in the publication of the tractates. The first paragraph of the Preface was written more than ten years earlier, i.e., no later than late 1910 or 1911. At that time the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim had completed, but not published, all the tractates mentioned in the first part of the Preface. Again, he did not publish the Preface itself until late 1921 or 1922. So although there is no date on Likutei Halakhot of Sotah itself, we can infer that it was published in תרפ”ב. As for the date of actual composition, we have no evidence in the Preface or anywhere else to suggest that it was written much earlier. Given that Niddah appears separately in תרפ”ג, the kuntres containing Sotah may have appeared late in תרפ”ב, after the aforementioned assembly of the Agudat Rabbanim in Warsaw. The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim would go on to complete other tractates and finish the work in 1925.

In short, the publication of Likutei Halakhot on Sotah is to be dated to late 1921 or the first two-thirds of 1922 (תרפ”ב) and not to 1911 or 1918,[22] according to the date of the aforementioned volume, and no earlier than Summer 1921, the date of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s return to Radin, according to the Preface.

Part II. The Historical Context of the Footnotes on Jewish Education in Likutei Halakhot on Sotah

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim was 83 years old when he declared it to be a great mitzvah to educate women in various Torah matters. To understand both the context and content of the statement, we first present the text and the two relevant footnotes. The main text of Likutei Halakhot on Sotah 11a (p, 21) may be translated as follows:

Rabbi Eliezer says, “Whoever teaches his daughter Torah teachers her tiflut.” You thought [actual] tiflut? Rather [it is] as if he teaches her tiflut. R. Abbahu says, “What is R. Eliezer’s reason? It is written, ‘I, wisdom, dwell with cunning,’** When wisdom enters a person, cunning enters with it.” And how do the Rabbis understand “I, wisdom”? The verse is needed for [the interpretation] of R. Yossi b. Rabbi Haninah, for R. Yossi b. R”H says, “The words of Torah stand permanently only for the person who makes himself naked for them, as it is written, ‘I, wisdom, dwell with nakedness.” In any event, the reasoning of R. Eliezer is not thereby rejected, and the halakha is according to his statement. [Later] rabbis said that “Torah” here refers davka to the Oral Torah. But even though the Written Torah should not be taught to one’s daughter ab initio,*** [teaching her Written Law] is not as if one teachers her tiflut. And women are obligated to learn from the Oral Torah the laws that pertain to them.[23]

(The asterisks refer to footnotes on this passage. Footnotes are rare in Likutei Halakhot, and rarer still are footnotes that refer to contemporary issues.)

Let us begin with the note preceded by three asterisks, on the prohibition of teaching the written Torah to women ab initio (based on M.T. Hilkhot Talmud Torah 2:13):

It seems that all this [the admonition not to teach written Torah ab initio to women] applies to previous times, when everyone dwelled in the place of his fathers, and the paternal tradition was very strong for each person to behave in the way that his fathers had tread, as the verse says, “Ask your father and he will tell you”. [Then] we could say that [a woman] should not learn Torah but should rely for her conduct on her upright fathers. But now, on account of our many sins, the paternal tradition has weakened considerably, and it is common that one does not dwell in one’s fathers’ location at all, and, particularly for those [women] who have accustomed themselves to learn to write and speak the languages of the nations, it is certainly a great mitzvah to teach them ḥumash, and also nevi’im and ketuvim, and the musar lessons of Ḥazal, such as tractate Avot, and Menorat ha-Ma’or, and the like, in order that our holy faith be confirmed for them. For otherwise, they are liable to stray completely from the way of the Lord, and to transgress all the foundations of the religion, God forbid.[24]

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim holds that the admonition not to teach women written Torah ab initio pertained to the past, when a woman could rely for her conduct on the example of her fathers. But today, we find a weakening of paternal tradition and the dislocation of the Orthodox from their paternal homes, which requires educating women, especially those women who are accustomed to learn the language of the gentiles; without Torah education, such women are likely to stray from the true path and to become heretics. What historical reality does this reflect?

As is well known, the use of legal literature as a source of history, even literature that purports to refer to historical events, is not unproblematic. On the one hand the geographical dislocation of Polish Jews because of the war indeed meant that many parents and children were no longer in the town and villages that had anchored their faith and practices for generation.[25] On the other hand, it would be wrong to infer from the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s remarks that in his view, pre-war Poland reflected a golden age of Jewish observance. Throughout much of his life he had railed against the weakening of observance among the Orthodox, and many of his published works tried to strengthen observance through teaching both the halakha and its centrality in the life of the Jew – and the penalties for its non-observance.

For example, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim was well aware that for decades there had been a weakening of traditional observance among women from some Orthodox homes. His son, R. Aryeh Leib Kagan, relates that when he came of marriageable age in the early 1880s, his father would not consider a match for him with a young woman from an Orthodox family who had attended a gymnasium (high school), or even an elementary school; such women and their families, even though they were Orthodox, were suspect in his eyes. In one case, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim ultimately forbade his son to accept an offer of the substantial financial assistance by a wealthy prospective father-in-law; it turned out that the prospective bride’s sister had been sent by her father to learn at a gymnasium in Grodno, where she had fallen in love with a gentile officer whom she had met (“presumably at the theater”), converted, and died in childbirth at the age of 15.[26]

In his 1905 handbook on family purity laws, Taharat Yisrael, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim attributes the decline of some women observing the mitzvah of mikveh to the shame they feel, not because of any foolish modesty (which is the case with some other women), but because they have been educated to look down at the laws of Torah. These women feel shame because

they have been raised in their free-thinking ways from their youth, when they attended schools, and became “wiser in their own eyes” than their predecessors, to the extent that they feel shame in observing the laws of the Torah according to the law of Moses and Israel, and particularly in a matter they consider to be beyond the boundaries of modesty.[27]

The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim responds to such women’s contempt of the Torah by providing well-worn arguments for its superiority and perfection. His defense is part of the larger project of the book, written both in Hebrew and Yiddish, to educate men and women in the importance of observing family purity laws. Urging Jews to observe Torah and mitzvot, and educating them for that purpose, is the leitmotiv that runs throughout the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s writings. Even his Likutei Halakhot on Kodeshim, though ultimately intended as an educational tool for learning Torah, was written as practical halakhic guide for the messianic age that Ḥafetz Ḥayyim thought imminent.[28]

This emphasis on deepening Torah observance in all sectors of the Orthodox community led him to publish a kuntres directed to women, Geder Olam, in 1889, on the importance of covering their hair. The kuntres was published in Hebrew and in Yiddish, and it includes at the end a basic halakhic guide to the laws of Niddah.[29] The halakhic guide was reprinted by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim in two other works: his book addressed to Jews migrating to places like America and South Africa, Nidhei Yisrael (1895), and his aforementioned book on family purity laws, Taharat Yisrael (1905); The Yiddish translation appears in all three works, which indicates that these sections were intended also for women to read.[30] Indeed, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim urges women who are literate to teach the book to women who are not, and to learn the Ma‘ayan Tahor of R. Moshe Teitelbaum of Ujhely (the Yismah Moshe) (reprinted many times in the Korban Minḥah siddur for women). The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim writes, “We have written only the legal principles that are most common, that all women are obligated to learn abundantly, and to become expert in them, so they not stumble because of them.”[31] This is a clear call for women to learn halakha, albeit in a rudimentary fashion, from books written for them.

From the above we see how important it was for the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim to write educational materials for women on family purity and female modesty. This in itself was a novelty; we are not aware of such materials being written in Lithuania at the time by Orthodox talmidei ḥakhamim of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s stature. Contrast, for example, the words of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s contemporary, Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, in Arukh ha-Shulḥan, Yoreh Deah 246:19:

Ours has never been the custom to teach [women] from a book, and we never heard of that custom. Rather every woman teaches the relevant laws to her daughter and daughter-in-law. Recently, laws pertaining to women have been published in the vernacular for women who can read from them. Our women are fervent (zerizot); in every doubtful matter they ask [a rabbi] and don’t decide for themselves in the smallest matter.[32]

To what recently-published laws pertaining to women was R. Epstein referring? Arukh ha-Shulḥan, Yoreh Deah was composed in the years, 1887-1894;[33] the early editions of Geder Olam were 1889, 1893, and 1894. In the latter, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim admonishes women who need to ask a halakhic question not to ask another women, but only a moreh hora’ah, “and for G-d’s sake, a woman should not dare to decide the law!”[34] It is very likely that R. Epstein was referring to this when he wrote, “Our women are eager; in every doubtful matter they ask [a rabbi] and don’t decide for themselves in the smallest matter.” Here we have two conflicting views on the education of women in practical halakha: R. Epstein sees no need to compose halakhic guidelines in Yiddish for women, since the women with whom he is familiar have learnt the material from their mothers or mothers-in-law and know when to ask questions. The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, observing women who are lax about observance, writes a halakhic/hashkafic manual in Hebrew and Yiddish that urges them (and their husbands) to study these guidelines diligently and to teach them to other women.

The importance of educating women in their religious duties, especially in the realm of family purity, remained with the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim for the rest of his life. As is well-known, he traveled to Vilna when he was old and frail to deliver a lecture in Yiddish at the central Synagogue on the importance of observing the mitzvah of mikveh in front of an audience of hundreds of women, with men listening in from the women’s gallery.[35]

To be sure, publishing educational materials on family purity for women is not the same as advocating Torah education for girls, but then, again, the situation in 1905 for Polish and Lithuanian Orthodox Jewry was not the same as in 1922. Orthodox Jewry in the Second Polish Republic was under severe stress. Dislocation and pressures – economic, ideological, and governmental — had accelerated the defection of Jews from the tradition; the dire situation provided an opportunity for conservatives to respond positively to new Orthodox initiatives to stem the tide. In particular, Orthodox Jewish education was at a crisis point, even more so for boys than for girls, which explains in part why much more attention was paid by Orthodox politicians and rabbis to the challenges facing the ḥadarim, than to the education of women, since, as we noted above, the compulsory education of law of 1919, which was in the early stages of implementation, required all Polish boys and girls to attend government certified schools. Agudat Yisrael negotiated repeatedly with the Polish authorities to have the ḥadarim certified, which meant that they needed to include subjects mandated by the Polish ministry of education; otherwise, even more ḥadarim would close. The negotiations with the government concerned how many hours of secular subjects would be taught, and what were those subjects to contain.[36] Formal Torah education for girls was already well underway, partly as a response to mandatory education, the general trend in female education, and the prevalence of alternatives to the ḥeder that attracted Orthodox parents, partly as a response to the weakening of observance among the Orthodox.

When the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim returned to Radin in 1921, he was faced not only with the fait accompli of formal Jewish education for women in Telz, Kovno, and elsewhere, but with the threat to both boys and girls posed by the implementation of universal compulsory education by the State. Unlike in Russia and Lithuania, compulsory education for Jewish girls had been the norm in Galicia, the part of Poland that had belonged to the Austrian Empire until the end of the First World War. Galician Jewish Orthodox girls, bereft of formal Jewish education, had attended Polish private and public schools for decades with disastrous consequences; the same now happened elsewhere in Poland. When, in his footnote, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim refers to “those [women] who have accustomed themselves to learn to write and speak the languages of the nations” he was, whether aware of it or not, referring to all Jewish girls in the Second Polish Republic, since, as Polish citizens even the strictest Hasidim were required to send their daughters to government certified schools. And unlike the case of their brothers, no Orthodox politicians negotiated with the government to exempt girls from these schools. School attendance for Hasidic girls was a well-entrenched tradition, even among the daughters of the zealots.

It is not surprising that the rabbi who raised the issue of women’s education at the assembly of the Polish Agudat ha-Rabbanim in 1922, Maharam Shapira, hailed from Galicia, where the situation had been bleak for decades. In his survey of the state of Orthodox Jewish education, he first turns to the challenges facing the ḥeder from the mandatory education law, on the one hand, and the attacks from the [Jewish] leftists (smoliyim) on the other. If the Polish government wished to spread general education among the people, it should take into consideration the most necessary requirements of the [Jewish] nation, which is the ḥeder. And if the Orthodox try to accommodate the government’s demands, it can only be in such a way that will not destroy the ḥeder. Most importantly, Orthodox boys need to be exempt from the obligation to attend general schools. And since the ḥadarim will now have to limit somewhat their hours for Jewish subjects, it is important that they be subject to universal standards, and that the instruction be overseen by experts and pedagogues. The Maharam Shapira then turned to the question of the education of girls:

We speak a great deal about the education of girls, which is a very painful subject for us. Our situation has become so bad because we have only taken a little interest in the subject for many years. At the same time as we devoted much of our thought, and always concerned ourselves, whether a lot or a little, with the education of boys, we continued to apply to the girls, “Kol kevudah bat melekh pnimah” as in earlier times, when a Jewish daughter did not come into contact and connections with the marketplace and the public sphere, and with the currents of the time that mostly oppose Yahadut. Then we did not need to give her an antidote and a powerful and effective counterforce against them. (“Whoever teaches his daughter Torah is as if he teaches her tiflut. (Sotah 20a).” Only men had in particular to learn Torah, for they needed the antidote – the countercurrent that repels foreign currents. But the daughter and the Jewish woman sat at home, where only that environment acted educationally upon them, and developed them and made them into true Jewish women and fit Jewish daughters.) We thus did not pay attention that the girls, unarmed and lacking any concept pertaining to Torah and Yahadut, have been taken outside from us into cultures and currents. They have become so educated and raised in the lap of foreign culture and anti-Jewish ways that every “common wind” and light attempt to ensnare their spirits, to penetrate into their souls, to poison and uproot them from their place, have wielded their evil ways upon them.

And we are faced with another grave question, which is strongly related with the education of the daughters, and this is the purity of the daughters of Israel….[37]

The Maharam Shapira diagnoses the illness but does not prescribe the remedy, anyway, not in the written version of his address. But as we saw above, the Assembly subsequently called for the establishment of Jewish schools for girls (supplementary to the general schools which they would attend). Connecting the crisis in the observance of the family purity laws with girl’s lack of education meant that rabbis like the Maraham Shapira understood that female observance of Jewish law could not be taken for granted. The Maharam Shapira also called for the production of Jewish youth literature, including textbooks, for the youth that would be free of all defect, and that would educate them in the spirit of faith and religion. This call was also ratified by the Assembly.

The question of the creation of textbooks that would be appropriate for use in ḥadarim seems to be alluded to in the earlier note in Likkutei Halakhot on Sotah on R. Abbahu’s explanation to R. Eliezer’s prohibition that “once wisdom enters into an individual, cunning enters with it.” The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim writes:

According to this, one should be even more careful not to teach boys and girls flippant writings and romances, which consume their heart and soul. One who reads them regularly is in the category of one who reads external books, who was treated with great severity by our sages, as is in the beginning of Helek (Sanhedrin 90). It makes no difference wheteher they are published in the Holy Tongue or the vernacular. See S. A. Orah Ḥayyim.307:16, and in the Mishnah Berurah ad loc.[38]

While attention in recent years has been focused on the footnote on Torah education for women, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s previous footnote on the education of boys and girls appears to have been entirely neglected. Why would a halakhic authority like the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim be concerned with teaching Orthodox Jewish boys and girls “flippant writings and romances”, i.e., literature written by Poles or by Jewish maskilim? Yet his concern makes sense in the context of the new Polish government’s requirement that general studies be included within the curriculum of the ḥadarim, and also in the context of Orthodox parents sending their children to non-Orthodox Jewish schools, like the Tarbut and Yiddishist schools. Even though the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim acquiesced to the limited introduction of secular subjects in the ḥadarim, we see from this note and the passage below that he insisted that only appropriate books be read by children. That was also the line taken by Agudat Yisrael in its attempts to control the growing popular youth literature, both in lending libraries youth, and in curricular materials for the ḥadarim and the Bais Yaakov schools under its auspices.[39]

In short, underlying both footnotes referring to contemporary matters in the Likutei Halakhot on Sotah are not the challenges of “modernity” in general, but rather the specific challenges facing the Polish Orthodox leadership in the interwar period brought about by the weakening of traditional authority, geographical dislocation, the introduction of universal primary education in the Second Polish Republic, and the attraction of Bundism, Zionism, and Socialism to the youth. Although the weakening of traditional authority, and the phenomena of Orthodox women attending Polish schools predated by decades World War I, the situation after the war threatened the very future of Torah Judaism in the eyes of the Orthodox establishment.

Part III. Other Statements of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim on Torah Education for Women

In the waning years of his life, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim returned several times to the question of Torah education for girls. Thus we read in his 1930 “Admonition to Kelal Yisrael”:

There is another principle that every talmid hakham in every town needs to enact, namely, to see to it that there is a kosher ḥeder in which our little sons (and also our little daughters) will be provided a kosher education in the way of the Torah, and not in schools that are full of heresy and sectarianism, which are completely bereft of teaching our holy Torah….

[One should accustom his son to learn the the aggadot of the Talmud…]. But even more one should distance his son from schools in which heresy and sectarianism is taught, where instead of the holy ḥumash, they make up books in which are found only stories of the ḥumash that they have copied without any sense of our Holy Torah – and that’s Torah in its entirety for them And all the laws and mitzvot like in Vayikra and Devarim they denigrate and do not copy. A father must be exceedingly careful not to allow his son to go to such schools where he destroys them with his own hands (and likewise he should be careful to educate his daughters in the way of Torah).[40]

And in a public appeal for the strengthening of religion that that he published in Sivan, 1931:

First of all, we must become fortified with all our strength in the education of boys and girls, to establish for them ḥadarim and kosher schools according to the law of our Holy Torah, not to deviate to the right or the left, or to forego anything of our Holy Torah, and not to allow them to attend such schools as are full of heresy and sectarianism, God save us….”[41]

We have found no mention of the importance of educating girls in the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s numerous writings devoted to education before World War I: educating women to observe and appreciate family purity, yes, but not teaching Torah to girls. This changed after the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s return to Radin in 1921. Already in 1922 there is abundant reason to believe that the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s foonote in Likutei Halakhot on Sota referred to formal Jewish education for girls, which was already well underway. As we noted above, his position was used to justify the establishment of schools for girls by the Agudah’s Keren ha-Torah in 1925. From the 1930s he made his position explicit: teaching Torah to Jewish daughters includes establishing “kosher schools” for them.

So it is hardly surprising that in 1933, when attempts to open a Bait Yaakov school in Fristik (Frysztak), Poland, were met with opposition by the local rabbi, R. Menachem Mendel Halberstam, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim signed a public approbation of Beit Yaakov in order to convince Jewish parents from the town to send their daughters to the school:

B”H 23 Shevat, Tarzag [= Feb. 19, 1933]

To the worthy lovers and esteemers of Torah, the Godfearing people of Fristik, may the Rock guard them,

When I heard that Godfearing people had devoted themselves to establish in the towns a Beit Yaakov school, in which is taught Torah, the fear of Heaven, morals, and manners, which is Torah for the girls of our Jewish brethren, I addressed their fine action [saying] “May the Lord strengthen them and establish the work of their hands!” For [that action] is a greatly needed matter in these day, when the current of heresy, God save us, reigns in all its force, and all sorts of freethinkers lie in wait to ensnare the souls of our Jewish brethren. Whoever’s heart has been touched with the fear of God is obligated to send his daughter to learn in this school. And there is no room for concern in this day and age for all the apprehensions and doubts arising from the prohibition of teaching one’s daughter Torah. This is not the place to elaborate.

For our generation is not as the earlier ones, for in previous generations each Jewish house had a paternal and maternal tradition to walk in the way of Torah and religion, to read Zeenah u’Reenah every Shabbat. But this is not the case, due to our many sins, in our generation. Therefore we must strive to increase schools such as these and to save everything that we possibly are capable of saving.[42]

The appeal seems to have worked because there was still a Beit Yaakov in Fristik in 1935, according to the list of schools provided by Deutschländer.

* * *

We conclude with a final comment: Some have inferred from the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s footnote in Likutei Halakhot and the appeal on behalf of Bais Yaakov schools that in his eyes formal education for girls should be considered “bediavad”, i.e., that in an ideal Jewish world, girls would not need to be taught Torah outside the home. If that is true, then the bediavad status of women’s education is somewhat akin to the bediavad status of the compilation of the Mishnah: in a world without the persecution and dispersion of the Jewish people, Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi would not have had to compile the Mishnah and thereby transgress the prohibition of committing Oral Torah to writing.[43] But the Torah, which is eternal, is adapted by the Torah sages in each generation to the world in which God-fearing Jews live. Formal Torah education for girls became for the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim “in this day and age” a “mitzvah gedolah,” in other words, lekhatkhilah, and his statements on the subject reflect that.

On the other hand, to say that it is a mitzvah gedolah to teach Torah and yirat shamayim to women is not to say that the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim wished to extend the commandment of Talmud Torah to include women.[44] That conflates the commandment of Talmud Torah, which applies only to Jewish men, with the obligation of teaching yiddishkeit to Jewish women through teaching them, inter alia, selections from Tanakh. While the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim emphasizes the former repeatedly and at great length in his writings and public activity, he barely mentions the latter. One need only compare his brief mention of teaching girls “ḥumash, nevi’im, ketuvim” in his footnote in Likutei Halakhot with his frequent statements about the necessity of teaching ḥeder boys ḥumash with Rashi “without skipping anything.” Even after his return to Radin, his public activities on behalf of women’s observance focused mainly on family purity, modesty, shabbat, and kashrut – not girls’ education.

Still, it is no wonder that the conservative Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, who had written numerous tracts to strengthen the observance and piety of Jewish baalei ha-batim and their families, embraced in later years the formal Jewish education of girls. Decades earlier he had called upon literate women to teach their illiterate sisters family purity laws from a book. He was not concerned with expanding the study of Torah among women, as much as expanding its observance and taking its message to their hearts. The Torah these girls were to be taught was a combination of Torah, the fear of heaven, morals, and manners. His goals were similar to that of Bais Yaakov movement, which was not to teach Torah to the daughters of Israel as an intellectual activity, or to make them life-long learners of Torah, but to form their character as religiously observant Orthodox Jewish women.[45]

Notes:

[1] Likute Halakhot on Sotah, 11ab (pp. 21-2). Unless otherwise stated, we have consulted the 1969-1970 edition of R. Menahem Mendel Yosef Zaks (Jerusalem, 1969-1970). This appears to be a reprint of the edition published in Brooklyn 10 years earlier.

[2] “This leniency enabled the opening of the first school of Beit Yaakov.” See Benjamin Brown, “The Baal ha-Bayit: R. Yisrael Meir ha-Cohen, the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim,” in Benjamin Brown and Nissim Leon, ed., Ha-‘Gedolim’: Ishim she-‘izvu et pene ha-Yahudut ha-haredit be-Yisrael. ed. (Jerusalem: Magnes, 2017), 106-151, esp. 133 (Hebrew)

[3] See Haym Soloveitchik, “Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Contemporary Orthodoxy,” Tradition, vol. 28, no. 4 (Summer 1994): 106-107 note 6.

[4] M. Yashar, Dos leben un shafn fun Ḥofets Ḥayyim (New York, 137), II, 377, 381.

[5] This is inferred from the celebration in Purim of 1931 of the school’s tenth anniversary.

[6] Yizhak Rafael Ha-Levi Etzion (Holzberg), “The Yavneh Educational System in Lithuania,” in Yahadut Lita (Tel-Aviv, 1972), II, 160-163

[7] According to one graduate of the school, “Chavatzelet’s general studies program was of a high caliber. It was headed by a non-religious woman and the teachers were either gentiles or secular Jews, since it was very difficult for a religious Jew to obtain the degree needed to teach secular studies. The religious studies, however, was not so successful […] The religious studies principal was the only religious faculty member – a Yekke (a German Jew). Under his influence Chavatzelet was conducted in the German manner of Torah im Derech Eretz. He taught us Chumash, Navi, history, and basic Hebrew grammar […] At any rate, the Torah portion of our education took only an hour of the day. The other six hours were devoted to secular studies.” Gutta Sternbuch and David Kranzler, Gutta: Memories of a Vanished World (Jerusalem and New York: Feldheim, 2005), 19-20.

[8] Ibid., pp. 17, 21.

[9] יא) לחנך את הבנות ברוח היהדות וללמוד עמהן מראשית ילדותן מעט מעט ד“ת ומוסר, וכפי רבות שנותיהן כן יוסיפו ללמוד עמהן היובים שעליהן באופן כשיגיעו לפרק נישואין יקבלו בנקל החיובים השייכם לטהרת בנות ישראל, והחברים מחויבים להשתדל שיתיסד בעירם בית ספר מיוחד לזה בעד הנערות. Peratei-kol me-ha-ve‘idah ha-rishonah shel agudat ha-rabbanim be-Folin (Warsaw, January 23-25), published at the end of Kovetz Derushim, Ḥelek Rishon, Keraḥ Sheni, ed. M. Warszawiak and Y. M. Sagaloṿits (Piotrkow, 1924), f. 9b.

[10] Mikhtavim u-maamarim mi-Maran Rabenu ba‘al ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, Ḥelek Bet, ed. Z. H. Zaks (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim [Jerusalem, 1990], IV, pp. 83-34)

[11] Leo Deutschländer, ed., Beth Jakob: 1928, 1929 (Frankfurt a. M.: Hermon, 1929), p. 7. Deutschländer cites the footnote and refers to it as a pesak din in Keren ha-Torah’s report on the state of Jewish education delivered at the Second World Assembly (ha-Knesiyal ha-Gedola) of Agudat Yisrael (Vienna, Elul,1929), 44-45. (The full report is available at https://hebrewbooks.org/36599.)

[12] In The Rebellion of the Daughters: Jewish Women Runaways in Habsburg Galicia (Princeton UP, forthcoming), p. 204, Rachel Manekin discusses a 1923 letter from Sarah Schenirer, in which she reveals that she consulted with the Belzer rebbe over whether the girls in her school could stage her play, Judith. Although the rebbe forbade staging it as “ḥuqqat ha-goy,” she expressed the hope that it could be performed as a declamation. From this one may infer that the Belzer rebbe was the school’s rabbinic authority until it came under the auspices of the Keren Ha-Torah of Agudat Yisrael in 1924-1925.

[13] See, for example, the letters in Mikhtavim u-ma’amarim, Ḥelek Bet, 24-39 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, IV, 24-39), and the kuntres, Torah Or at the end of Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, II.

[14] See Likutei Halakhot, Second Introduction, f. 6a-b.

[15] Ibid., f. 7a

[16] Likutei Amarim, ch. 7, pp. 10-12, esp. p. 11 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim III).

[17] The Bar Ilan University Library web catalogue lists a copy of Likutei Halakhot on Zevaḥim with prenumerants, bound with the gemarrah of Zevaḥim, that dates from 1891/2. See R. Aryeh Leib ha-Kohen’s account of the delays in publishing Likutei Halakhot in his biography of his father, Mikhtevei ha-Rav ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, ed. Aryeh Leib ha-Kohen, p. 51, in Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III. R. Aryeh Leib saw his father’s decision to write on Kodeshim, in part, as a reaction to the wave of migration to Eretz Yisrael from Eastern Europe following the expulsion of Jews from Moscow in 1890-1891, and the sense of messianic expectation; see ibid., pp. 38-39.

[18] M. Gellis, Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim…reshimah bibliografit (Jerusalem, 1984), p. 56. Brown (see n. 2 above) relies on Gellis.

[19] The date also appears in Shoshana P. Zolty, And All Your Children Shall Be Learned: Women and the Study of Torah in Jewish Law and History (Northvale, N.J: J. Aronson, 1993), p. 67, n. 34 (The place of publication is given as “St. Petersburg” rather than Piotrków.) An edition of Likutei Halakhot, Part Two, of R. Natan Sternhartz, was published in Warsaw in 1918-1919; perhaps this explains the confusion

[20] וב“ה על י״ג מסכתות ששייכים לעניני קדשים והם זבחים ומנחות ותמיד ופסחיס (מפרק תמיד הנשחט עד ערבי פסחים) וחגיגה ויומא ותמיד ותמורה וכריתות ובכורות (שלשה פרקים אחרונים), וערכים ומעילה ונזיר (שגם היא יש בה הדבה ענינים ששייכים לקדשים) וכן שני פרקים הראשונים ממסכת שבועות על כל אלו לקטנו בעניות דעתנו מדברי הרמב״ם מה שהעתיק מהסוגיות לדינא […].וכעת אין חסר מן הש“ס רק איזה מסכתות יתן ד׳ שבמשך הזמן ימצאו בישראל משליטים לכל הש״ס […]

[21] והנה כל זה כתבתי יותר מעשרה שנים ועבר עלינו נדודים הרבה מפני המלחמות וב״ה ששם נפשינו בחיים ולא נתן למוט רגלינו. וכעת שבאתי מן הגולה בשלום לביתי עזרני הש״י ברוב חסדו וטובו בזכות כלל ישראל להשלים הליקוטי הלכות גם על יתר מסכתות של הש״ס שאין עליהם רי״ף ורא״ש (ואלו הן ראש השנה וסנהדרין ומכות והוריות וסוטה ונדה […]) ]. The Ḥafetz Ḥayyim mentions that there are other tractates on which there are no Rif and Rosh, and he suggests that others may come to complete his work. In fact, he himself completed the work and revised the Preface in 1926; the revised Preface was published posthumously as chapter seven (“A Worthy Article on the Study of the Holy Torah”) in Likutei Amarim, pp. 10-12 (In Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III.)

[22] Although Deutschländer writes in his 1929 historical account of Bait Yaakov schools that their legal sanction had been provided “decades ago” (vor Jahrzenten) by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim in Likutei Halakhot on Sota, he may have been unaware of the publication history of Likutei Halakhot. In any event, he does not repeat the claim in his more detailed Hebrew report, published in the same year. For references see n. 8 above.

[23] ר‘ אליעזר אומר כל המלמד את בתו תורה מלמדה תפלות. תיפלות ס“ד אלא כאילו מלמדה תפלות. א“ר אבהו מאי טעמא דרבי אליעזר דכתיב אני חכמה שכנתי ערמה מכיון שנכנסה חכמה באדם נכנסה עמו**) ערמומית. ורבנן האי אני חכמה מאי עבדי ליה מיבעי ליה לכדר‘ יוסי ברבי חנינא דאמר רבי יוסי בר“ח אין ד“ת מתקיימין אלא במי שמעמיד עצמו ערום עליהן שנאמר אני חכמה שכנתי ערמה ומ“מ לדינא אין נדחה מפני זה סברת ר‘ אליעזר ונקטינן כן להלכה. וכתבו רבוותא דהיינו דווקא תורה שבע“פ אבל תורה שבכתב אף שאין ללמדה ***) לכתחילה מ“מ המלמדה אינו כמלמדה תפלות וגם מתורה שבע“פ הדינים השייכים לאשה מחוייבת ללמוד.

[24] **ונראה דכל זה דווקא בזמנים שלפנינו, שכל אחד היה דר במקום אבותיו, וקבלת האבות היה חזק מאוד אצל כל אחד ואחד, להתנהג בדרך שדרכו אבותיו, וכמאמר הכתוב ‘שאל אביך ויגדך‘; בזה היינו יכולים לומר שלא תלמוד תורה, ותסמוך בהנהגה על אבותיה הישרים. אבל כעת בעוונותינו הרבים, שקבלת האבות נתרופף מאוד מאוד, וגם מצוי שאינו דר במקום אבותיו כלל, ובפרט אותן שמרגילין עצמן ללמוד כתב ולשון העמים, בוודאי מצווה רבה ללמדם חומש וגם נביאים וכתובים ומוסרי חז“ל, כגון מסכת אבות וספר מנורת המאור וכדומה, כדי שיתאמת אצלם עניין אמונתנו הקדושה; דאי לאו הכי עלול שיסורו לגמרי מדרך ד‘, ויעברו על כל יסודי הדת ח“ו”

[25] According to Leo Deutschländer’s report of Keren ha-Torah at the Second Kenesiya Gedolah in Vienna in 1929, between 40 and 50 thousand children had been taken from their parents during the war and its aftermath, and these children had grown up without Torah, ethics, education, and faith. See Ha-Kenesiyah ha-Gedolah ha-Sheniyah shel Agudat Yisrael, ed. Shabbetai Sheinfeld (Vienna, 1929), p. 29. The situation among Polish Orthodox youth led Agudat Yisrael to establish, for the first time in Poland, organizations for the purpose of strengthening the faith and commitment of the younger generation. See Gershon C. Bacon, The Politics of Tradition: Agudat Israel in Poland, 1916-1939 (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1996), 181-141.

[26] Mikhtevei ha-Rav ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, pp. 20-22, in Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III.

[27] Taharat Yisrael, ch. 8, pp. 10-11, esp. 10, in Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III.

[28] See Mikhtevei ha-Rav ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, pp. 53-54, in Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III.

[29] This guide is attributed in the early editions of Geder Olam to a יצחק בר“ז, who says that they are based on the tract, Dinei Niddah, by Shlomo Zalman Lifschutz, the authors of the Ḥemdat Shelomo on the Shulhan Arukh. יצחק בר“ז is likely the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s close associate in Warsaw, R. Isaac b. Zeev (“Itche”) Grodzienski. According to R. Aryeh Leib Kagan, R. Grodzienski translated Geder Olam into Yiddish in a second printing, in 1890, which explains why the name Isaac is on the title page. However, the first 1889 edition also has both Yiddish and Hebrew and more to the point, subsequent editions remove all mention of Isaac. Since the the Yiddish appears in two other books by the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim printed under his own name, one assumes that the Yiddish translation, too, was the work of the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, perhaps in partnership with R. Grozdienski

[30] The reference to the Dinei Niddah of the Ḥemdat Shelomo is omitted in these works. The Yiddish is absent from R. Zaks’ edition, which also omits the chapter on family purity in Geder Olam. It was not unusual for the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim to reuse parts of his kuntresim.

[31] Geder Olam (Warsaw 1889), f. 19 ,p. 37.

[32] Arukh ha-Shulhan (Jerusalem, 1969), VI, f.18, p. 35.

[33] Eitam Henkin, “The Books of the Arukh ha-Shulhan – The Order of Their Composition and Their Publication,” Ḥitzei Giborim –Pleitat Soferim, vol. 7 (2014): 515-536, esp. 516 (Hebrew), available online here (https://tinyurl.com/y8t7a7ncThis).

[34] Ed. 1895, 15a, p. 29

[35] For the Yiddish address, with Hebrew translation, see Kol Kitvei ha-Hafetz Ḥayyim III, 171-174.

[36] For an account of these negotiations, and the “quiet revolution” in Orthodox education, see Bacon, The Politics of Tradition, pp. 147-177.

[37]מדברים אנו הרבה ע“ד חנוך הבנות, שהוא אצלנו שאלה מכאבת מאד. מצב הענין הזה רע אצלנו כל כך משום שאך מעט מזעיר התענינו בו שנים הרבה, בה בשעה שעל אודות חנוך הבנים הרבינו לחשוב מחשבות ולהתעניין בו תמיד ברב או במעט, השארנו הבנות על חשבון “כל כבודה בת מלך פנימה“, כבשנים קדמוניות, בשעה שבת ישראל לא באה כל כך ביחס וקשור עם השוק ורשות–הרבים, עם זרמי העת המתנגדים לרוב להיהדות ולא היינו צריכים ג“כ לתת לה איזו תבלין וכח–מנגד חזק נגדם. (‘כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאילו למדה תפלות‘ תורה היו צריכים ללמוד ביחוד רק הגברים, שהיו נחוצים להם תבלין, זרם–מנגד ודוחה לזרמים הזרים, אולם הבת והאשה הישראלית ישבו להן בביתן, במקום שרק הסביבה פעלה עליהן פעולה חנוכית ופתחה ועשתה אותן לבנות ישראל כשרות ויהודיות אמתיות). לא שמנו אפוא את לבנו לזה, כי גם הבנות מוצאות לחוץ, ברשות הרביות וזרמים זרים המזורה לרגליהן, בהיותן אי–מזוינות, בלי היות להן כל מושג בתורה ובהיהדות, נתחנכו ונתגדלו בחיק תרבות זרה, ודרכים אי–יהודיים, וכל רוח מצוי‘ וכל נסיון קל לצודד נפשותיהן ולחדור לתוך נשמותיהן ולהרעיל ולעקרן ממקומן – פעלו עליהן את פעולתם הרעהץ עומדות לפנינו עוד שאלה חמורהת הקשורה בקשר אמיץ עם חנוך הבנות והיא טהרת בנות ישראל.

[38] **) הערה ולפ“ז כ“ש שיש ליזהר מללמד להנערים והנערות כתבי לצון ובדברי חשק שזהו ממש מכלה לבן ונפשן והמרגיל עצמו בזה הוא בכלל הקורא בספרים החצונים שהחמירו החכמים מאוד בזה כדאיתא בריש פרק חלק (סנהדרין דף צ) ואין נ“מ אם הם נדפסות בלשה“ק או בלשון לע“ז ועיין בשו“ע או“ח בסימן ש“ז סט“ז ובמ“ב שם.

[39] The Maharam Shapira, in the aforementioned address to the Polish Agudat ha-Rabbanim, also remarks on creating appropriate literature for Jewish youth.

[40] עוד ישנו עיקר גדול שעל כל הת“ח שבכל עיר לתקן והוא לראות שיה‘ בעירו חדר כשר שבו יתחנ כובנינו הקטנים (וגם הבנות הקטהות שלנו) בחינוך כשר בדרך התורה ולר בבתי ספר כאלו המלאים כפירה ומינות שאין בהם שום זכר ללמוד תורה“ק… אבל ביותר צריך להרחיק את בנו מבתי ספר כאלו שלומדים שם כפירה מינות, שבמקום החומש הקדוש המציאו ספרים כאילו שבהם נמצאו רק סיפורי החומש שהעתיקו אותם בלי שום טעם וריח של תורה“ק, וזה להם כל הצורה כולה. וכל דיני התורה והמצוה כמו ספר ויקרא וספר דברים בזו להם ולא העתיקם כלל…ומאד מאד יזהר האב, מלהניח את בניו ללכת לבתי ספר כאלה שהוא מאבד בידים את בניו (וה“ה גם בנותיו יזהר לחנכן בדרך התורה) Mikhtavim u-ma’amarim, Ḥelek Bet, pp. 56-57 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, IV). For the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s attack on the “methods” pedagogy of the non-Orthodox Hebrew schools, see Ḥomat ha-Dat, pp. 20, 52-55 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, II), and his 1927 appeal against teaching the Bible in this fashion in Mikhtevei ha-Rav ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, pp. 24-26 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III)

[41]ראשית הדבר,עלינו להתחזק בכל כחנו בענין חנוך הבנים והבנות,ליסד עבורם חדרים ובתי ספר כשרים כדין תורה“ק, שלא להטות ימין ושמאל ושלא לוותר על שום דבר מתורה“ק ולא להניחם ללמוד בבתי ספר כאלו, מלאים כפירה ומינות, ר“ל…. “Appeal for the Strengthening of Religion,” in Mikhtevei ha-Rav ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, p. 99 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, III).

[42] ב“ה, יום כ“ג לחודש שבט תרצ“ג אל כבוד האלופים הנכבדים חובבי ומוקירי תורה החרדים לדבר ה‘ אשר בעיר פריסטיק נ“י. כאשר שמעתי שהתנדבו אנשים יראים וחרדים לדבר ד‘ ליסד בערים בי“ס “בית יעקב” ללמוד בו תורה ויר“ש מידות ודרך ארץ זו תורה לילדות אחינו בני ישראל. אמרתי לפעלם הטוב יישר ד‘ חילם ומעשה ידיהם יכונן כי ענין גדול ונחוץ הוא בימינו אלה. אשר זרם הכפירה ר“ל שורר בכל תקפו והחפשים מכל המינים אורבים וצודים לנפשות אחב“י וכל מי שנגעה יראת ד‘ בלבבו המצוה ליתן את בתו ללמוד בבי“ס זה וכל החששות והפקפוקים מאיסור ללמד את בתו תורה אין שום מיחוש לזה בימינו אלה. ואין כאן המקום לבאר באריכות. כי לא כדורות הראשונים דורותינו אשר בדורות הקודמים היה לכל בית ישראל מסורת אבות ואמהות לילך בדרך התורה והדת ולקרות בספר “צאינה וראינה” בכל שבת קודש מה שאין כן בעוונותינו הרבים בדורותינו אלה. ועל כן בכל עוז רוחנו ונפשנו עלינו להשתדל להרבות בתי ספר כאלו ולהציל כל מה שבידינו ואפשרותנו להציל. הכותב למען כבוד התורה והדת ישראל מאיר הכהן, in Mikhtavim u-ma’amarim, Ḥelek Bet, pp. 24-39 (Kol Kitvei ha-Ḥafetz Ḥayyim, IV).

[43] See Mishneh Torah, Introduction. Although Rambam does not say explicitly that the compilation of the Mishnah was a violation of the prohibition of writing Oral Torah down, he suggests that the compilation was a novelty required by the travails of the time. For a look at this question see Michael Wygoda, “‘You Are Not Permitted to Write Down Oral Statements,’ On the Development of a Forgotten Halakha,” Dimuy 26 (1996): 48-63 (Hebrew).

[44] Cf. Benjamin Brown, “The Value of Torah Learning in the Ḥafetz Ḥayyim’s Writings and His Ruling on Women’s Torah Learning,” Diné Yisrael, vol. 24 (2007): 79-118, esp. 116-11

[45] For this see Manekin, The Rebellion of the Daughters, 182-235.