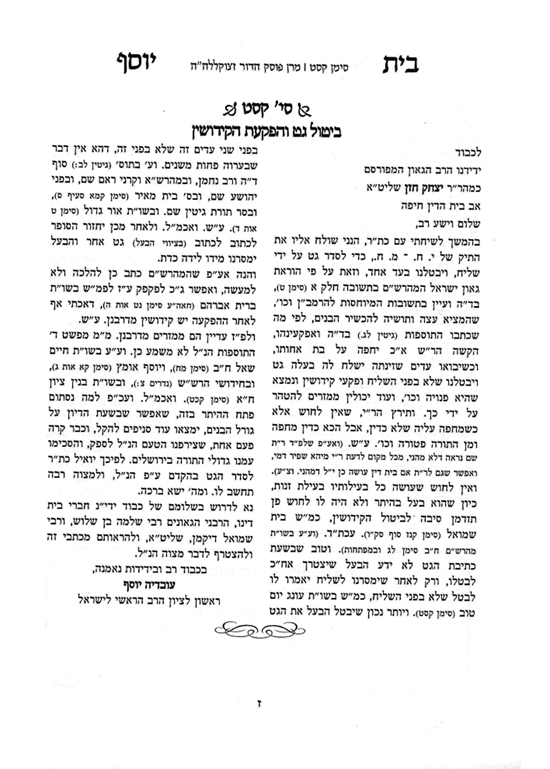

The Haftarot of the Sabbaths of Hanukkah and the Haftarah of the Sabbath of Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet

The Haftarot of the Sabbaths of Hanukkah and the Haftarah of the Sabbath of Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet[1]

by: Eli Duker

In the Babylonian Talmud (Megillah 31a) it is stated that the haftarah for the Sabbath of Hanukkah is from “the lamps of Zechariah,” and if Hanukkah coincides with two Sabbaths, the haftarah for the first Shabbat is from “the lamps of Zechariah” and the haftarah for the second Shabbat is from “the lamps of Solomon.”

Rashi there explains that “the lamps of Zechariah” refers to the haftarah beginning: “Sing and rejoice” (Zechariah 2:14), and that “the lamps of Solomon” refers to the haftarah beginning: “Hiram made” (I Kings 7:40). This explanation is also found in Seder Rav Amram Gaon, and this is the practice in most communities to this day.[2]

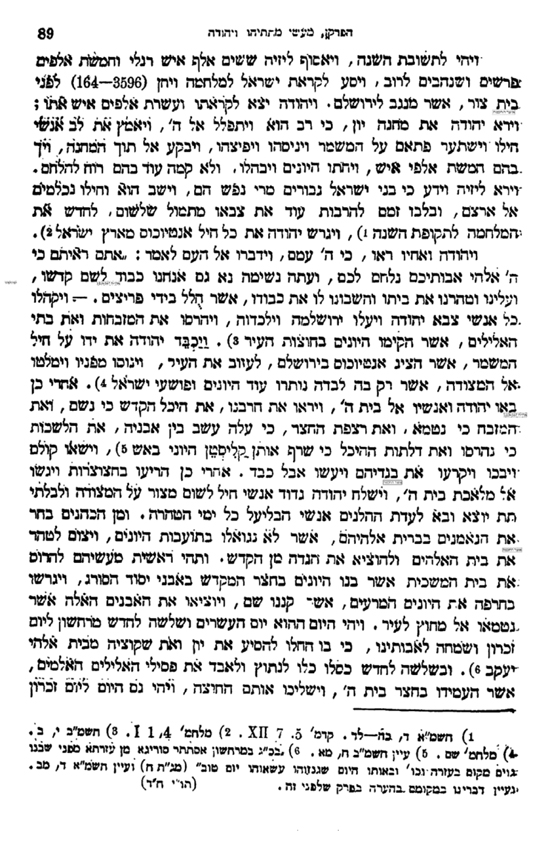

We find another custom in Tractate Soferim (20:8) with regard to the Torah reading and haftarah for the Sabbath of Hanukkah:

ובשבת שבתוכו קורא ויהי ביום כלות משה, עד כן עשה את המנורה, וכן ביום השמיני, עד וזה מעשה המנורה, ומפטיר ותשלם כל המלאכה.

Thus, according to Tractate Soferim, the haftarah for the Sabbath of Hanukkah begins: “When all the work was completed” (I Kings 7:51), which addresses the dedication of the First Temple. It is somewhat puzzling that the haftarah begins precisely there and not a few verses earlier, which would have included the “lamps of Solomon,” a fitting verse for Hanukkah. It is possible that since Tractate Soferim generally reflects the practices of Eretz Yisrael, and the miracle of the cruse of oil is a Babylonian tradition, they saw no need to refer to the making of the menorah. Yet, we see that according to this ruling they nevertheless read in the Torah up to the account of the making of the menorah, even though according to the Mishnah only the passages of the nesi’im are read — indicating that there is a desire to allude to the miracle of the cruse of oil.[3] One can suggest that since the menorah was already mentioned there, they did not see a need to allude to it again in the haftarah.

Tractate Soferim does not mention a Torah reading or haftarah for the second Sabbath of Hanukkah. Concerning Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet that falls on a Sabbath, it is stated there (20:12):

דר’ יצחק סחורה שאל את ר’ יצחק נפחא, ראש חדש טבת שחל להיות בשבת במה קורין, בעניין כלות, ומפטיר בשל שבת וראש חדש.

The “haftarah for Sabbath and Rosh Ḥodesh” refers to what is stated elsewhere in Tractate Soferim (17:9):

ובזמן שחל ר”ח להיות בשבת השמיני שצריך לקרות וביום השבת ובראשי חדשיכם הוא מפטיר (יחזקאל מ״ו:א׳) בכה אמר [ה”א] שער החצר הפנימית הפונה קדים.

In Pesikta Rabbati[4] there are homilies on no fewer than three haftarot for the Sabbaths of Hanukkah: “Elijah took twelve stones” (I Kings 18:31), “When all the work was completed” (I Kings 7:51, similar to the haftarah in Tractate Soferim), and: “It will be at that time that I will search Jerusalem with lamps” (Zephaniah 1:12). Each of these sections in the Pesikta begins with a halakhic question relating to Hanukkah.

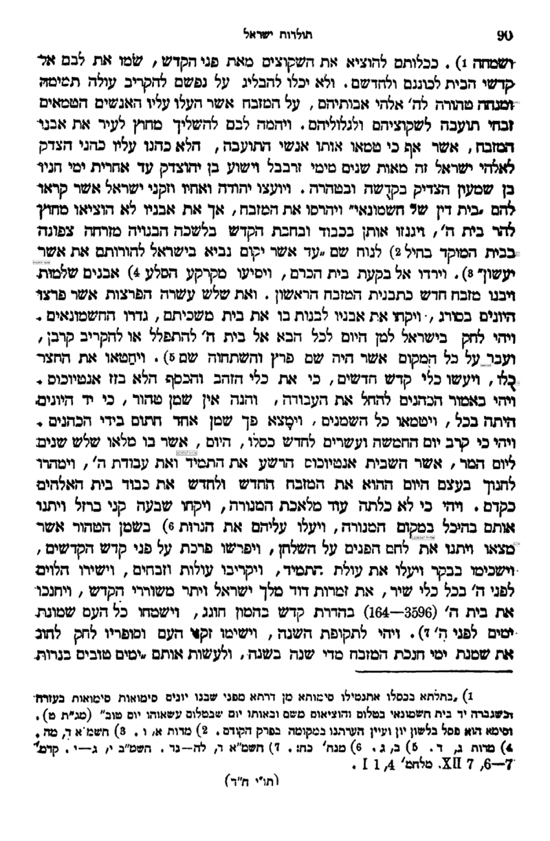

In Piska “Elijah took” (4) we find:

ילמדנו רבינו: ראש חודש שחל להיות בחנוכה, הואיל שאין תפילות המוספין בחנוכה, מי שהוא מתפלל תפילת המוספין מהו שיהא צריך להזכיר של חנוכה? למדונו רבותינו אמר רבי סימון בשם רבי יהושע: ראש חודש שחל להיות בחנוכה אף ע”פ שאין מוסף בחנוכה אלא בר”ח, צריך להזכיר של חנוכה בתפילת המוספים. שבת שחלה להיות בחנוכה אע”פ שאין מוסף בחנוכה אלא שבת, צריך להזכיר של חנוכה בתפילת המוספין. והיכן הוא מזכיר? בהודאה.

It is noteworthy that the question is formulated primarily with regard to the Musaf of Rosh Ḥodesh during Hanukkah, even though it obviously applies equally to the Musaf of the Sabbath of Hanukkah, as reflected in the answer. Rabbi Meir Ish Shalom already noted in his commentary in his edition of Pesikta Rabbati[5] that it is reasonable to assume this is the haftarah for the Sabbath of Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet. The connection between this haftarah and Rosh Ḥodesh likely lies in what appears later in the same passage in the Pesikta:

אתה מוצא שנים עשר חודש בשנה, שנים עשר מזלות ברקיע, שתים עשרה שעות ליום ,ושתים עשרה שעות לילה. אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: אפילו העליונים והתחתונים לא בראתי אלא בזכות השבטים שכך כתב “את כל אלה ידי עשתה” (ישעיה סו:ב), בזכות כל אלה שבטי ישראל שנים עשר (בראשית מט:כח) (לכך שנים עשר מזלות, שתים עשרה שעות). לכך כיון שבא אליהו לקרב את ישראל תחת כנפי השכינה נטל שתים עשרה אבנים למספר השבטים ובנה אותן מזבח. מניין? ממה שהשלים בנביא “ויקח אליהו שתים עשרה אבנים למספר שבטי בני יעקב”.

In Piska “It will be at that time” (8) we find:

ילמדנו רבינו: מהו שידליק אדם נר שישתמש בו מן הנר של חנוכה? תלמוד, למדונו רבותינו א”ר אחא בשם רב (אמר) אסור להדליק נר שישתמש בו מנר של חנוכה, אבל נר של חנוכה מותר להדליק מנר של חנוכה.

In Piska “When all the work was completed” (6) we find:

ילמדנו רבינו: נר של חנוכה שהותיר שמן מהו צריך לעשות לו…

It is therefore possible to suggest that in Pesikta Rabbati there is Zephaniah 1:12 for the first Sabbath of Hanukkah that is not Rosh Ḥodesh, and I Kings 7:40 for the second Sabbath of Hanukkah. In addition, there is I Kings 18:31 as a haftarah for a Hanukkah Sabbath that is also Rosh Ḥodesh. This is an appropriate haftarah for this time due to description of the victory over the prophets of Baal—which parallels the Hasmonean victory over the Greek kingdom—and the recurring motif of twelve, which is appropriate for Rosh Ḥodesh.

By contrast, all other sources from Eretz Yisrael (Tractate Soferim and the piyyutim mentioned below) point to I Kings 7:51 as the sole haftarah for the Sabbath of Hanukkah, read not only when there are two Sabbaths of Hanukkah. Moreover, in the Pesikta, the Piska of “When all the work was completed” immediately follows “It was on the day that Moses finished,” which is the Torah reading for a regular Sabbath of Hanukkah (or at least when Shabbat falls on the first day of Hanukkah).[6] For this reason, B. Elitzur claims[7] that “When all the work was completed” was read specifically on the first Sabbath of Hanukkah, and “It was on the day” was read on the second Sabbath. It should be noted that the Piska “It was on the day” is adjacent to the Piska “The one who brought his offering on the first day,” not to the Piska “On the eighth day” (to which the section “And Elijah took” is adjacent).[8]

In the Kedushta piyyut of Yannai[9] for the Sabbath of Hanukkah, the verse “When all the work was completed” appears as the first verse in the chain of verses in the meshalesh, indicating that this was the haftarah. Likewise, this verse also appears in the Meḥayyeh of the Kedushta piyyut of Rabbi Yeshuah son of Rabbi Joseph.[10] There is nothing in these piyyutim to indicate they were composed specifically for the second Sabbath of Hanukkah.[11] In light of all these sources—which mention only a single haftarah for the Sabbaths of Hanukkah (despite the approximately five-hundred-year gap between Yannai and Rabbi Yeshuah)[12]—the customs reflected in Pesikta Rabbati were likely very rare in both time and place.

In a comprehensive study of Rabbi Eleazar ha-Kalir’s Kedushta piyyutim for Hanukkah, A. Mintz-Manor identifies no fewer than five potential haftarot for the first Sabbath of Hanukkah. In the piyyut “Adir Kenitzav,” the Kalir cites the verses “When all the work was completed,” as well as “Solomon built the House and finished it” (I Kings 6:14), and “Thus said Hashem: Behold, I will restore the fortune of the Jacob’s tents” (Jeremiah 30:18).

In the piyyut “Meluḥatzim Me’od Bera,” “Behold, I will restore” also appears, as well as “I will search Jerusalem” (which appears as a haftarah in Pesikta Rabbati), and another potential haftarah: “Solomon brought the peace offering” (I Kings 8:63).

In the piyyut “Otot Shelosha” for a Sabbath that is both Hanukkah and Rosh Ḥodesh, both the verses “The gate of the inner court” and “When all the work was completed” appear, indicating that in his time there was no uniform custom in Eretz Yisrael for this Sabbath, with some reading the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah and others reading the Hanukkah haftarah. Yet, the fact that the verse from the haftarah of Rosh Ḥodesh appears first may indicate that that was the preferred haftarah.

In the piyyut “Menashe Ve’et Efraim,” written for the second Sabbath of Hanukkah, the haftarah is “On the eighth day he sent the people off” (I Kings 8:66). It is possible that this is the same haftarah that appears in “Meluḥatzim Me’od Bera,” with a few earlier verses added.

Summary of Haftarot

| Haftarah | Source(s) |

|---|---|

| I Kings 7:51 | Tractate Soferim; piyyutim of Yannai, Kalir, Rabbi Yeshuah; Pesikta Rabbati |

| Zephaniah 1:12 | Piyyutim of Kalir; Pesikta Rabbati |

| Jeremiah 30:18 | Piyyutim of Kalir |

| I Kings 8:63 | Piyyutim of Kalir |

| I Kings 6:14 | Piyyut of Kalir |

A Geniza fragment[13] records both customs with regard to Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet (and Adar and Nisan) that fall on a Sabbath. According to the custom in Eretz Yisrael, two Torah scrolls are taken out. The passage for Hanukkah is read first, and then that of Rosh Ḥodesh. According to the Babylonian custom, where the weekly portion is read as well, that is read first, followed by Rosh Ḥodesh and Hanukkah. According to both customs, the haftarah there is for Hanukkah.[14]

From all the above, we see multiple differing customs regarding the Sabbath of Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet:

- Haftarah of Rosh Ḥodesh – Tractate Soferim; one mention in Kalir.

- Haftarah of Hanukkah – one mention in Kalir; a Geniza fragment.

- A special haftarah – Pesikta Rabbati.

We find in the Geonic literature that the haftarah of Hanukkah is read, as stated in a responsum of Yehudai Gaon:

תוב שאילו מן קמיה: הקורא בתורה בראש חדש חנוכה ושבת בשל ראש חדש מפטיר או בשל חנוכה? ואמר בשל חנוכה.

There is a similar statement in Halakhot Pesukot[15] and the Siddur of Rav Amram Gaon.[16]

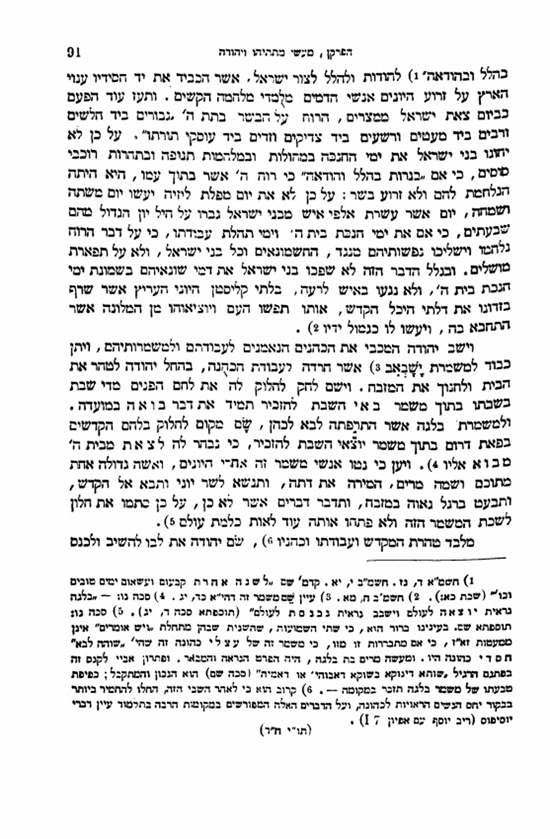

In Early Ashkenaz, where the Hanukkah haftarot followed those in the Talmud Bavli, there existed differing customs concerning the haftarah for a Sabbath of Hanukkah that coincided with Rosh Ḥodesh. In the Siddur of Rashi (321) we find:

ואם חל ראש חודש טבת להיות בשבת, התדיר קודם. מוציאין שלש תורות, וקורין ששה בעניינו של יום, והשביעי ובראשי חדשיכם, ומפטיר קורא בחנוכה ובנבואת זכריה [רני ושמחי], והשמים כסאי בטלה, דהא לא קרי מפטיר בראש חדש דלימא הפטרה דיליה. ובמס’ סופרים גרסינן שמפטירין בשל ראש חדש, אבל לא נהגו העם כן: ושמעתי שנחלקו במגנצא שני גדולי הדור ר’ יצחק בר’ יהודה ור’ שמואל בר’ דוד הלוי, ר’ יצחק ציווה להפטיר ברני ושמחי, ור’ שמואל העיד מפי אביו שאמר לו שמפטירין בשל ראש חדש וקיימו את עדותו, וכמדומה שחולקין כן בראש חדש אדר שחל להיות בשבת, ואנן נוהגין [להפטיר] ביהוידע.

From this passage it emerges that although Tractate Soferim states that the haftarah should be that of Rosh Ḥodesh, this was not the common practice. Rashi records that in Mainz two leading sages of the generation disagreed: Rabbi Yitzḥak bar Yehudah ruled to read beginning from Zechariah 2:14, whereas Rabbi Samuel bar David ha-Levi testified in the name of his father that the haftarah should be that of a standard Rosh Ḥodesh on the Sabbath, and his testimony was accepted. Rashi adds that a similar disagreement seems to have existed regarding Rosh Ḥodesh Adar that falls on a Sabbath, concerning which he records that the practice was to read “Yehoyada.”

This material appears as well, with slight variations, in Sefer ha-Pardes.[17]

It is recorded in Ma‘asei ha-Geonim:

ואילו תשובות שהשיב רבי’ ר’ משלם בר’ משה ממגנצא לאחי לר’ נחומי’. וששאלת ר”ח טבת שחל להיות בשבת במה מפטירין? יש מבני קהלינו שאומרים שמפטירים ברני ושמחי ויש מהם שאומרים שמפטירין בהשמים כסאי ואבאר טעמם של אלו וטעמם של אלו מיושר על המחיקה אותן שאומרין להפטיר בנירות של יהוידע[18] אומרים כן היא המדה לעולם שבאותו עיניין שהמפטיר קורא באותו עיניין (ש)צריך להפטיר הוי קורא בשל חנוכה. ואם נפשך לומר יקרא בשל ר”ח ויפטיר בשל ר”ח, אינה היא המידה שהרי תדיר ושאינו תדיר תדיר קוד’. וטעמם שאומרי’ להפטיר בשל ר”ח או’ ר”ח דאורייתא וחנוכה דרבנן ולא אתי דרבנן ודחי דאורייתא. ומצינו בהלכות גדולות שצריך להפטיר ברני ושמחי אבל במקומינו נהגו להפטיר בשל ר”ח מפני כבודו של רבי’ יהודה הכהן הזקן שהורה [כן] וקיי”ל מקום שיפול העץ שם יהו פירותיו.

It is clear from these sources that Rabbi Yehudah ha-Kohen ha-Zaken and Rav David (cited by his son Rav Shmuel), both students of Rabbeinu Gershom—and Rabbi Samuel bar David, ruled to read the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah. Beyond the claim that Rosh Ḥodesh is by Torah law, they were evidently also aware that this was the ruling in Tractate Soferim.

By contrast, Rabbi Yitzḥak bar Yehudah—who studied under Rabbeinu Gershom but was primarily a disciple of Rabbi Eliezer ha-Gadol[19]—ruled in Mainz to read the Hanukkah haftarah despite the rulings of Rabbi David and Rabbeinu Yehudah ha-Zaken. Out of respect for the latter authorities, this ruling was not adopted, even though it was known that Halakhot Gedolot ruled in that direction (apparently referring to Halakhot Pesukot, as cited in Or Zarua).

In the Ra’avan we find a continuation of this position, including a statement that Rabbi Yehudah ha-Kohen’s sons also ruled to read the haftarah of Rosh Ḥodesh:

וראש חודש טבת שחל בשבת בחנוכה נחלקו בהפטרה. הגאונים רבינו רבי יהודה הכהן ובניו היו מורין להפטיר בהשמים כסאי מטעם תדיר ושאינו תדיר תדיר קודם. ועוד, מדאמרינן [כ”ט ב] דאין משגיחין בדחנוכה תחילה וראש חודש עיקר, למה לי למימר ראש חודש עיקר, אלא אפילו להפטרה. ועוד, מדמפורש בהפטרה “מידי חודש בחדשו ומידי שבת בשבתו” ואין דוחין שתים, שבת ור”ח, מפני אחת, חנוכה. והחלוקין עליהם אומרים כיון שהמפטיר קורא בדחנוכה צריך להפטיר בדחנוכה. וחקרתי אני אליעזר בסדר רב עמרם גאון, ולא הזכיר בו כלל השמים כסאי, אלא כך כתב בו, שבת של חנוכה קורין בנירות דזכריה רני ושמחי ואם יש ב’ שבתות בשבת ראשונה קורין רני ושמחי.

Here we see the same tendency noted earlier with Rabbi Samuel bar David: the sons of Rabbi Yehudah ha-Kohen followed their father’s ruling to read the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah. Ra’avan notes that others disagreed, though he does not name them—presumably he refers to Rabbi Yitzḥak bar Yehudah and perhaps his son Rabbi Yehudah, who sought guidance regarding his father’s rulings.[20] It appears from Ra’avan’s language—though not definitively—that he personally examined the Siddur of Rav Amram Gaon and followed it in determining who to follow concerning this dispute among the scholars of Mainz.

It is noteworthy that in Sefer ha-Minhagim of Rabbi Abraham Klausner[21] and also in the Maharil[22] it is stated that the opinion of “Eliezer”[23] was to read the haftarah of Rosh Ḥodesh.

We find Maḥzor Vitry (239):

ואם חל ראש חדש בשבת התדיר תדיר קודם. ומוציאין ג’ תורות. וקורין ששה בעיניינו של יום. והשביעי ובראשי חדשיכם. ומפטיר קורא בחנוכת המזבח. לפי עניין היום. ומפטיר בנבואת זכריה. רני ושמחי: על שם ראיתי והנה מנורת זהב: והשמים כסאי בטילה. דהא לא קרי מפטיר בשל ראש חדש דלימא הפטרה דידיה: ובמס’ סופרי’ גר’ שמפטירין בשל ראש חדש. אבל לא נהגו העם כן. ושמעתי שנחלקו שני גדולי הדור במייאנצא. ר’ יצחק בר’ יהודה צוה להפטיר ברני ושמחי. ור’ שמואל בר’ דוד הלוי העיד משום (אבא) [אביו] שמפטירין בשל ראש חדש. וקבלו את עדותו: וכמדומה לי שחלוקין בין ראש חדש אדר שחל להיות בשבת. (דאין) [דאנן] נוהגין להפטיר ביהוידע.

It is evident from this statement that there existed a clear custom—apparently in France—to read the haftarah of Hanukkah despite their awareness of the dispute in Mainz.

Subsequently Rabbi Shimon of Sens (Tosafot, Shabbat 23b) stated unequivocally that Hanukkah haftarah should be read.

הדר פשטה נר חנוכה עדיף משום פרסומי ניסא – ונראה לרשב”א כשחל ר”ח טבת להיות בשבת שיש להפטיר בנרות דזכריה משום פרסומי ניסא ולא בהשמים כסאי שהיא הפטרת ר”ח. ועוד כיון שהמפטיר קורא בשל חנוכה יש לו להפטיר מענין שקרא. ומה שמקדימים לקרות בשל ר”ח משום דבקריאת התורה כיון דמצי למיעבד תרוייהו, תדיר ופרסומי ניסא, עבדינן תרוייהו, ותדיר קודם. אבל היכא דלא אפשר למעבד תרוייהו פרסומי ניסא עדיף. ועוד דבקריאת התורה אין כל כך פרסומי ניסא שאינו מזכיר בה נרות כמו בהפטרה. ועוד נראה לרשב”א דעל כן הקדימו של ר”ח כדי שהמפטיר יקרא בשל חנוכה ויפטיר בנרות דזכריה.

Tosafot hold that the reason why the Torah reading of Rosh Ḥodesh precedes that of Hanukkah is precisely so that the haftarah should be that of Hanukkah.

The Rash cited in Tosafot there adds another claim: Publicizing the miracle is far more prominent in the haftarah of Zechariah than in the Torah reading, which does not explicitly mention lamps.

Over the generations in Ashkenaz, both customs are recorded in the Rishonim such as Ravyah, Or Zarua, and Mordechai. Yet, in Ravyah—similarly to Ra’avan—there is a clear inclination toward reading the Hanukkah haftarah:

ואי איקלע פרשת שקלים בראש חדש אדר מפטיר בבן שבע שנים, דמיירי בשקלים מעין שקלים דכי תשא שקרא המפטיר, וזה הכלל שהמפטיר הולך אחר הפרשה שקרא הוא עצמו. ויש חולקים ואומרים להפטיר בראש חדש לעולם, מפני שהוא תדיר. וכן שבת וראש חדש וחנוכה מפטיר ברני ושמחי מעין הפרשה שקרא בה המפטיר. וכן כשחל פרשת שקלים בכ”ט בשבט מפטיר בבן שבע.

By contrast, Shibbolei Haleket[24] cites Rabbi Yehudah HaḤasid as ruling that one should read the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah.

In Sefer ha-Minhagim of Mahara of Tirna, it is stated that the opinion of the Mordechai is to read the Hanukkah haftarah, and this is how it appears in the Vilna edition of the Talmud. Yet, the Machon Yerushalayim edition has an addition that appears in manuscript:

וכן נמצא בתשובת רב יהודאי גאון[25] אך רבי יהודה כהן הביא ממסכת סופרים ובהלכות פסוקות של ספר והזהיר[26] וברכות ירושלמי[27] שמפטירין בדר”ח, ונלאיתי לכתוב ראיות.

Despite this, according to the other French sources the practice was to read the Hanukkah haftarah. In the Sefer ha-Minhagim (76) attributed to Rabbeinu Abraham Klausner—though the core of the work is actually by Rabbi Paltiel (of French origin)[28] —it is stated:

ומפטיר רני ושמחי, וכן מנהג הרבב במיידבורק. לעולם נגד מה שקורין המפטיר מפטירין. וה”ר אליעזר אומר דמפטירין השמים כסאי ואין משגיחין בדחנוכה, אע”פ כשחל ר”ח אדר בשבת מפטירין בן שבע שנים, היינו משום דמיניה קא סליק משקלים, לכך משקלים מפטירין דדמי’ ליה ושבקיה דר”ח, אבל הכא לא דמי רני ושמחי לפרשת נשיאים כלל, הילכך מפטירין בדר”ח דדמי’ לפרשת שבת ולפרשת ר”ח שנא’ “מדי חדש בחדשו ומדי שבת בשבתו”, והכי אמרינן במסכת סופרים, שאל ר’ יצחקה לר’ יצחק נפחא ר”ח טבת שחל להיות בשבת במה קורין א”ל בענין ויהי ביום כלות משה, ומפטיר בר”ח ושבת והיינו מדי חדש בחדשו וגו’.

This passage introduces a new claim: The haftarah of Hanukkah does not correspond to the Torah reading of the Nesi’im at all, and therefore should not override the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah. This represents at least one French source inclined toward the Rosh Ḥodesh haftarah. These views are cited in the glosses of the Maharil, though the Maharil himself ruled to read the Hanukkah haftarah.

Ultimately, the Rosh, the Tur,[29] and the Abudirham[30]—and following them the Shulḥan Arukh and the Levush (with the Rema not offering a dissent)—all ruled that the haftarah of Hanukkah is read. This is the practice observed in all communities today.

- I would like to thank my brother R’ Yehoshua Duker for his help in editing this, and Dr. Gabriel Wasserman for discussing the piyyutim with me. This article is written לזכר נשמת ייטא בת הרב שמואל יוסף who just passed away. Her emunah and mesirat nefesh in Auschwitz and in her long life afterward is a source of inspiration for her extended family and beyond. ↑

- See my site on Alhatorah, with regard to the Algerian practice not to read a special haftarah for the second Sabbath of Hanukkah ↑

- See E. Fleischer, The Formation and Fixation of Prayer in Eretz Yisrael, pp. 449–450 (Heb.). He understands that the reading for the last day of Hanukkah when it fell on the Sabbath was not the entirety of Numbers 7 but only similar to today’s practice. The issue of the tradition of the miracle of the oil is beyond the scope of this article. ↑

- Concerning the haftarot for Hanukkah in Pesikta Rabati, see Elitzur, B. “Pesikta Rabati: Pirkei Mevo” pp.77-79. ↑

- Piska 8 fn. 1. ↑

- See Fleisher. ↑

- Elitzur p. 77. ↑

- Elitzur. ↑

- Mahzor Piyuttei Rabbi Yannai LeTorah Velamoadim, Vol, 2. p. 237. ↑

- https://maagarim.hebrew-academy.org.il/Pages/PMain.aspx?mishibbur=954001&page=1 and Elitzur S. “Piyyutei Rabbi Yeshuah Birbi Yoesf Hashofet” p.11 fn. 46 and pp 28-20 in Kovetz Al Yad 5774. ↑

- Fleisher pp. 451-452, and fn. 32. ↑

- Rabbi Yeshuah was a dayan in 11th century Alexandria. See Fleisher, ibid. ↑

- Oxford Bodl. Heb. e. 93/3. ↑

- Fragment is in Judeo-Arabic, translated by Fleisher pp. 449-250 and fn. 22. ↑

- P. 185. ↑

- P. 36. ↑

- Budapest Edition, p. 144 ↑

- Ms, 6691=31. It is not clear why Yehoyada is mentioned here. Perhaps it is due to confusion with the son of the First Temple era Zechariah, or perhaps it is due to the same issue existing with regard to Rosh Ḥodesh Adar of Sabbath when the haftarah is about Yehoyada; see Mahzor Vitry, cited below. ↑

- Grossman, Ḥakhmei Ashkenaz Harishonim pp. 302-303. ↑

- Ibid. p 301. ↑

- Machon Yerushalayim edition, p. 65, Halacha 76. ↑

- Machon Yerushalayim edition, p. 410. ↑

- I.e., Raavan; see notes in books above. ↑

- Inyan Hanukkah, Siman 190. ↑

- It seems he is referring to the Halakhot Pesukot. ↑

- We do not have this source. See Shibbolei Haleket, Zichron Aaron edition, siman 190 fn. 32. ↑

- This source does not appear in today’s editions of the Yerushalmi. Many thought that Rishonim had a “Sefer Yerushalmi” that was an addition to the standard Talmud Yerushalmi. Several decades ago, texts were found in the bindings of books in various European libraries that may be this work. See Zusman Y. “Seridei Yerushalmi Ktav Yad Ashkenzi (Kovetz Al Yad 1994, especially pp.15-17). Later he writes how the Mordechai (Beitzah 2:682) cites a Yerushalmi not known to us, and it was found there.

As I am unaware of anything from Tractate Berakhot from this Geniza, it is uncertain what the Mordechai is referring to, but he is likely referring to this work here as well. See Zussman’s “Yerushalimi Ktav-Yad VeSefer Hayerushalmi” in Tarbitz (1996) pp. 37-63, as well as Mack. H. “Al Hahaftara Beḥag Simchat Torah” in Meḥkerei Talmud 3 vo. 2 pp. 497-8 fn. 44. ↑ - See the introduction to the Machon Yerushalayim edition. ↑

- Oraḥ Ḥayyim 684. It is the same in other sources using this numbering. ↑

- Hanukkah. ↑