Augsburg and its Printers

Augsburg and its Printers: Printer of the Tur in Ashkenaz: Fragments Censored at the Beinecke’s Augsburg Mahzor

By Chaim Meiselman

Chaim Meiselman catalogs rare books for the Joseph Meyerhoff Collection, originally at Baltimore Hebrew Institute, now at Towson University. He is a bibliophile and intermittently a book dealer. This is his first contribution to the Seforim Blog.

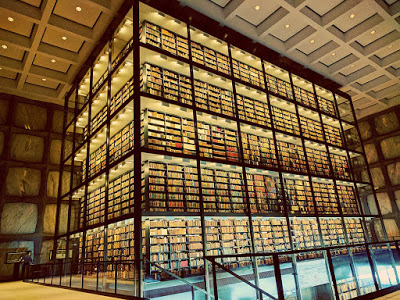

Last summer, I was at Yale University for a conference. Those who have spent time at Yale University will know that their libraries are separated by major subject, and therefore are situated in different buildings. While I was spending a good amount of the time at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library for material covering manuscripts, I was able to use downtime for perusing their Rare Book Collection.

This library is a breathtaking edifice erected for books. For those who haven’t had the opportunity to visit it, I highly recommend going, even for a non-research purpose. The reason why I recommend it is because one can see a modern-day example of something which used to be more common during the previous centuries – a temple dedicated to literary craft. As is with many commercial buildings built during the last century, libraries have evolved into storage containers of some kind; this building is built exhibiting manuscripts and books in rich light. Six of the seven stories of volumes are visible from the balcony, where they exhibit items and one can tour the inside.

Here is a picture of the vantage from the inside.

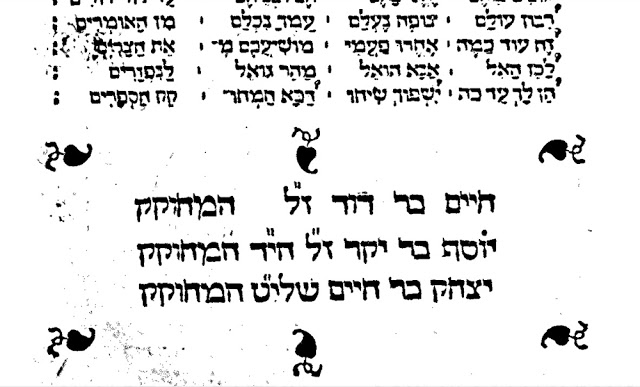

Among their collection of hebrew books is a copy of the very rare imprint of the Machzor ke-seder ha-Ashkenazim, the volume of Machzor printed in Augsburg in 1536 by Haim “ha-mehokek” b. David Shahor (see here). This is a rare and revolutionary title for a number of reasons, some of which I’ll write here.

While I own a facsimile of the Shahor volume, I’ve never before held it in hand. It is about the size of a large size Mechon Yerushalayim Tur, thinner though. The pages were darkened by light exposure but the type was still fresh. More below on his imprint of Tefillos.

The first question (which is relevent to what discovery i will share here) is – who is Haim Shahor. Hayyim b. David Shahor was among the earliest printers of Hebrew books north of the Alps; born in the late 15th century, likely in Ashkenaz, he was involved earlier in Hebrew print than Bomberg and Giustiani, and earlier than Bak, Prosstitz, and Jaffe in ‘Ashkenaz’. He is documented as having printed in tiny hamlets earlier than 1535 – Heddernheim, Oels (Schliesen), yet more famously Augsburg.

Augsburg was where Shahor printed his Siddur, his Machzor, and his Turim. Comparably few copies were created; for every Augsburg volume, Moritz Steinschneider (CLHB) writes “fol. Rara” or “ed. Rara”. Libraries which contain volumes of Hebrew Incunabula often don’t contain a print of Shahor, certainly not an Augsburg volume – they are extremely scarce.

There have been claims that Shahor may have been a Christian printer disguising himself as a Jew. These are very unlikely, and probably aren’t true; in one of the Augsburg printings, a long Tefillah and colophon puts this claim in doubt.

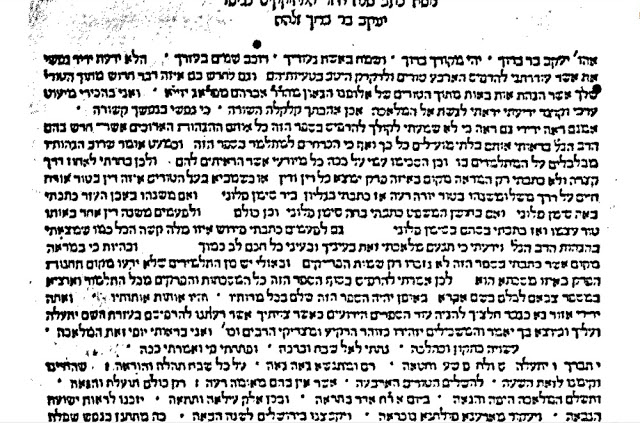

I am pasting copies of the one scanned on Hebrewbooks.org. However, this scan is extremely low resolution, even for HB. If there is a high resolution scan done of the volume, one will be able to see the precise and sharp magnificence of this font, almost like that of Ketav Ashurit. This is an adaptation of the Ashkenazic script from manuscripts centuries older, and it carries that appearance somewhat.

As I see it, it is highly unlikely that this was a Christian family printing – Yosef b. Yakar writes to his brother in law, Ya’akov b. Baruch that he has emended the printing format of the Luach ha-Simanim (in which the Mare’h ha-Mekomot are brief and added are a longer Luach preceding each of the Seder ha-Turim). Many of the examples of the “Luach Gadol” in this Tur no longer exist, making full examples of these even more rare – but they were written in heavy “Rashi script” – and if they aren’t the first tables of contents in printed Hebrew Books, they are almost certainly are the most lengthy and encompassing.

Briefly referenced is a disagreement (regarding this format) with Avraham of Prague, who is a noted editor on the other Augsburg volumes (and selected other Shahor printings).

I will quote a passage from this here: אמנם ראה ידידי … כי לא שמעתי לקולך להדפיס בספר הזה כל אותם ההגהות הארוכים אשר חידש בהם הרב הנ”ל … וכמעט אומר שרוב ההוגותיו “מכלכלים” (מקלקלים) על התלמידים בו … וכן הסכימו עמי. Below, he details exactly what the differences were, and he immediately offers words of thanks for being able to put out this edition, the first Tur to be printed in Ashkenaz, but one which is “without defects”: על כל שבח תהלה והוראה. שהחיינו וקיימנו לזאת השעה. להשלים הטורים ארבעה. אשר אין בו מאומה רעה. It is clear that the novelty of the printed Turim is paramount in the thought of the printers, however what is mentioned and repeated is לחדד התלמידים, כדי שלא יקלקלו התלמידים, and such scripts on the idea of studying the Tur and teaching it to students. This theme isn’t one of Christian influence, especially being that there already was a debate on the proper methods of studying Halacha raging at the time – this language feeds to this writing. Although it was at this time of a smaller scale (because of the not-yet published Bet Yosef and Shulchan Arukh and the later writings on the subject of Rama, Maharal, Maharshal, and R. Yoel Sirkis), the statement completing the enormous printing process was like the one above is directly showing a Rabbinic influence, not a Christian one.

After the letter of Yosef b. Yakar, Shahor writes a “Shevach Tehilla” for finishing the volume. He repeats this theme: בחור תראה | הן תשתאה | ספר נאה | בהדורים |רבה הון מה | לך תתהמה | פן יהיו מה | הד נמכרים … ישמח יסגא | כל בם הוגה | כי ממשגה | הם נשמרים | קונים מהם | יהגו בהם | הם ובניהם | עד דוד דודים | As before, I see it that this is related to the theme of the debate of the proper methods to learn Halacha, and not to neglect the study of Gemara (as it had been in Ashkenaz at the time, according to some accounts.)

Another reason it is highly doubtful that Shahor was a crypto-christian was that his granddaughter married the printer Kalonymus Jaffe, famously as printer (including the printing of the Shas and the Turim) in Lublin. He was the first cousin to R. Mordechai Yaffe, known as the Ba’al ha-Levush; his father Mordechai printed the first copies of the Levushim. This is another hint that Shahor was from a learned Jewish background, not that of a Christian printer. As is documented, from Shahor’s family descended generations of printers in Prague, Krakow, and other centers of printing in Central Europe. See Marvin J. Heller, Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, pg. 149-151.

In the entry for the Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics (Brill, 2013) title “Hebrew Printing” by Brad Sabin-Hill, it is recorded that Shahor was working among presses owned by Christian humanists; this is likely, in the light of what I will record below.

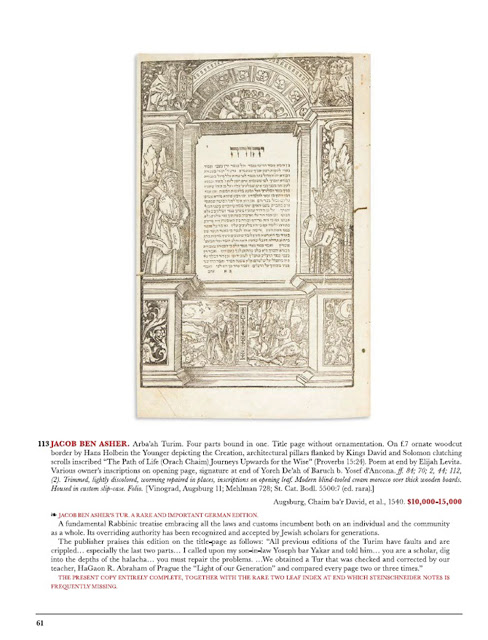

Leaf 7, the opening leaf of the text of the Tur, is supposedly illustrated by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), an important late-Renaissance artist originally from Augsburg. I’m not certain where this information is from. Here is the catalog entry from the Selected Catalog of the Valmadonna Trust Selections, which sold at Kestenbaum’s on November 9th.

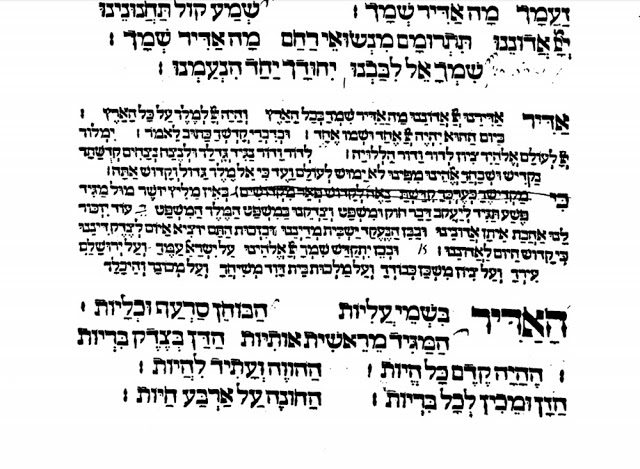

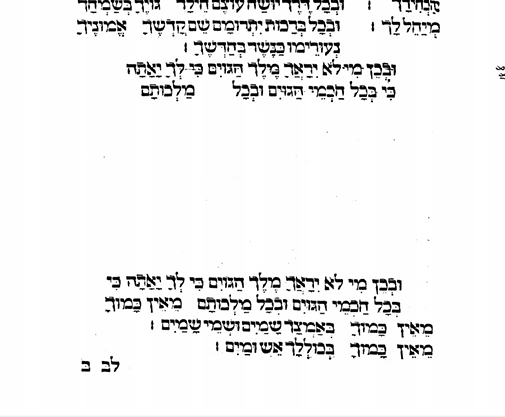

Back to the Mahzor. Among the differences this Mahzor has with the other editions, one that should be noticeable (as relating to the editor and printer) is the self-censorship of a Piyyut. For the Yom Kippur Piyyutim recited during Shacharit, a Piyyut is supplicated in after אדיר אדירנו. Even though in the Mahzor it is recorded after ובכן יתקדש … ועל מכונך והיכלך, it follows the heading האדיר, and opens another acrostic lines into the Piyyut מי אדיר אפסיך – perhaps this is because of the re-use of the text block for the repeating paragraphs of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur davening.

This is how it appears:

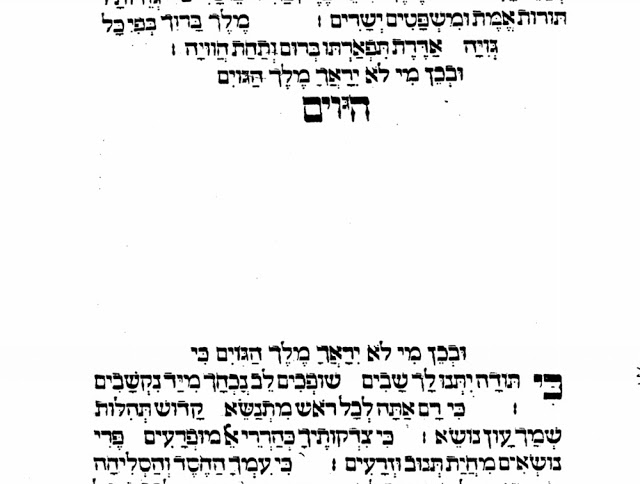

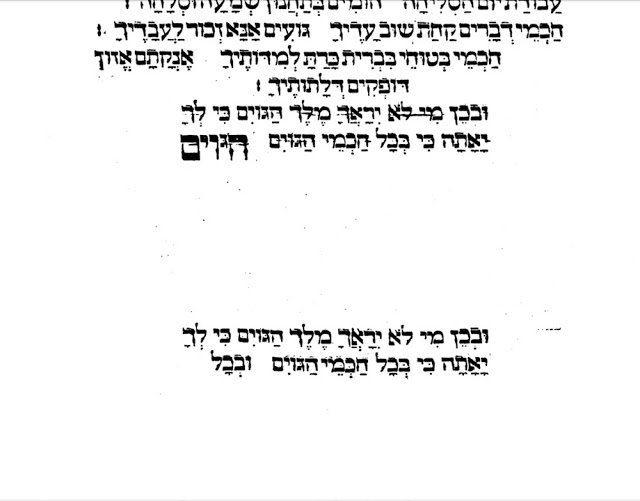

For the Piyyut headed by האדיר, an acrostic begins using Jer. 10:7, מי לא ייראך מלך הגויים, כי לך יאתה: כי בכל-חכמי הגויים ובכל-מלכותם, מאין כמוך. In that Piyyut, there is a portion which was censored in virtually every text. However, the Augsburg Mahzor self-censors three blocks, which would’ve likely been offensive in the eyes of the Church. Although it is possible that he did it out of consideration not to offend the Humanists who had granted him the rights to print (if it is true that this was the case for this printing), it is entirely plausible that he wanted the text to be supplemented by a scribe and didn’t want the internal work of a censor to be involved (both at the time of print and the future viewers).

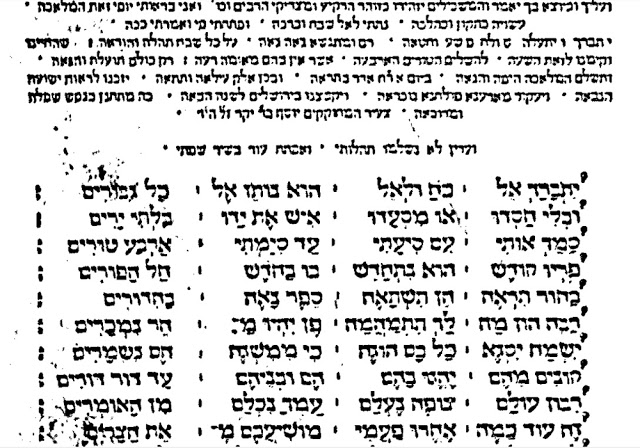

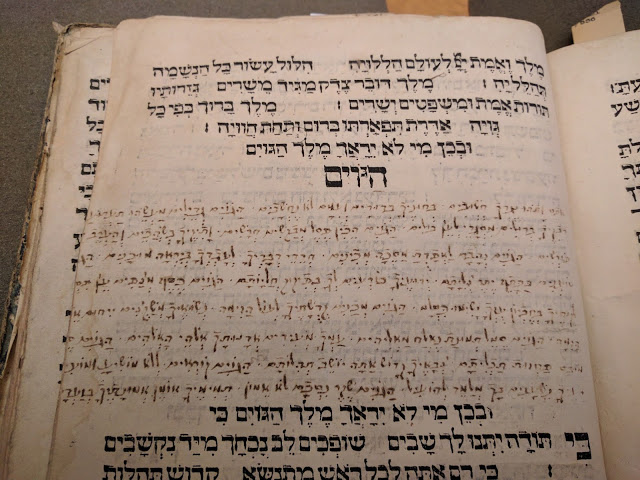

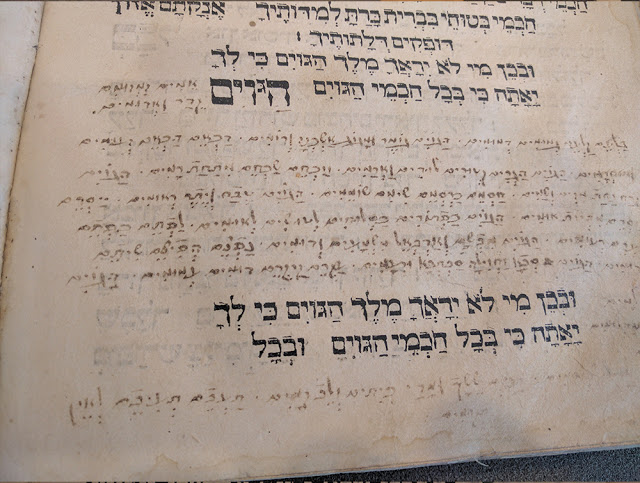

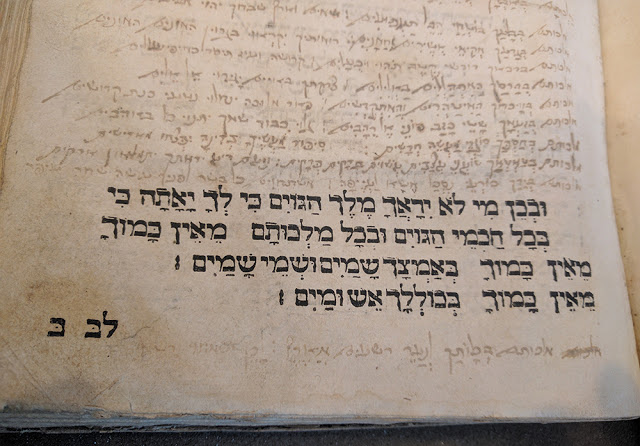

This is how they look:

Back to the copy at Yale. In the copy I was holding, I saw that it was inscribed with the missing pieces.

There was a scribe who wrote in the margins, crossed through printing mistakes, and marked pieces which would be relevant to a Shaliach Tsibbur. Examples of פזמון, קהל, בניגון, and a type of cantillation abound in the volume by his hand. At the end, he signs his name as ‘Shelomoh b. Ya’akov halevi’ .

The script appears to me to be from the time the volume was printed. It utilizes flourishes and specific criteria of script that I recognize from the hands of (and from the time of) R. Yoel Sirkis, R. David Halevi (Ta”z), and other handwriting of the era.

The themes of the Piyyutim with the inscription additions are now complete, as you can see with my writing below. The paragraphs, especially the second one, are very harsh in their ‘attack’.

First, I will paste photos of the pages:

The writing has faded, and is difficult to make out in some areas. However, I transcribed what was there.

Edited to add: Marc Shapiro pointed out that variants of these paragraphs are in the Goldschmidt Mahzor. I will paste here the my transcription of the written paragraphs in text and Goldschmidt (where he differs strongly) in bold type.

Paragraph one:

הגוים

אפס ותהו נגדך חשובים: בחוניך בדודים לעם לא נחשבים: הגוים גדילים מעשיהו תעתוע והבלים

דבקיך בדולים מסגרי מסגודי לעץ בולים: הגוים הכין פסל מבקשים חרשים: ותיקיך בשהכים והערב [ייחודיך

פורשים: הגוים זהבם לאפדת מסכה מכינים: חרדי דבריך לעבדיך ליראה מוכנים: הגוים]

[שועגים טוענים בכתף יתר כליתם: ידועיך כורעים לך בפיקוק חליותם: הגוים כסף מצפים עץ מסגריהם]– פסלם

לקחיך בחביון עזך ישימו כסלם: בגוים מכנים קדשתך לעול הזימה: נשואיך משקצים ייחוס ע[רוה]-

וזמה אשת הזמה : הגוים סמל תמונת נאלח מאליהים: עמך מעידים אדנותך אלהי האלהים: הגוים

פגר מובס בחנות פחזות תכליתם צבאך קדוש אתה יושב תהלותם: הגוים קוראים ללא מושיע ומוע—יל

רעך נשענים בך מלמד להועיל : הגוים שקר נכסם לא אמון תמימיך אומן אמונתיך בועד(ם)

ינעמון

ובכן מי לא ייראך מלך הגוים וכו

Paragraph two:

יאתה כי בכל חכמי הגוים הגוים-אמים (זמזומים)

קדר לאדומים. ואדומים

בלעם קלעים גמומים דמומים. הגוים גומר ומגוג אשכנז ורומים. דכאם הכאם זעומים

למוחרמים הגוים הגרים כעורים טורים קטורים לודים ואראמיים. ייכחם וכחם שכחם מתחת רמים. הגוים

זרם נחת מקיצים מזים ושמים. חמסם כרסמם שימם שוממים. הגוים טבח ליתר ראומים. ייסרם

סדם הסירם מהיות אומים. הגוים כפתורים כסלוחים כפלתחים לטושים לאומים . לפתם כפתם

צערם סעורים רעועים. הגוים מבשם ואדבאל משמעים ודומים. נפצם הפילם הפיצם שיתם

הדווחים הדמים. הגוים סבא וחבילה סבתכא ורעמים. ישרם עקרם קרקרם דומים דוויים נמומים. הגוים

פלשת אמון אשור בין אשור לעילמים

צמתם המיתם תנם ייתם למהלומים

—– (לירדם)

קיר ומואב לודים וענמים רטשם נטשם דקים צנומים

שישך ומדי כמים ולב-קמים תעבם העיבם לאין תקומים

זקשם —- לדמים. חכים ששך למדי כיתים ולב רשעים. תבעם תעיבם לאין

מן המים: ובכן מי לא ייראך מלך הגוים…. וכוליה

Paragraph three:

ובכן מי לא יראך מלך הגוים כי לך יאתה

כי ככל חכמי הגוים ובכל מלכותם

מלכותם באבדך עבדי ניטנים פסילי נסכים: תוכן מלכותם תיכון מלכותך מלך מלכי המלכים

מלכותם [בבלעך] בוטחי הבל תעתועים: שמים לארך שבחך יהוי אביעים

מלכותם בצרעך בגדעך מקימי אשירים לחמנים: רומותיך יקראו בגרון המונים המונים

מלכותם בדכאך דורשי קטב תהו ובעלים: קדושה ועוז תיסד כמפי עוללים?

מלכותם בהרסך המתהללים באללילים : צדקתך באיים יגידו באיים אל אלים

מלכותם בווכיך המטהרים והמקדישים: פאר מלוכה ינחלו ככוכבי נטעי כנת קדושים

מלכותם בזעמך שטי כזב פוני אל רהבים: גלו עלוי כבוד שמך יתנו כל באהבים

מלכותם כחסדך בחשפך סוגרי מעשה חדשים: סיפור מעשיך ברינה יפצחו מארישים

מלכותם בטחטאח שועגי טועני עצבים עשוים ברקים ברקים פרקים : וינעם דינו דע יראתך יתממון יתמאלון זורקים

מלכותם בידך כורעי נסבל אשא לעייפה: משתחוים כל בשר לפניך עושה שחר עיפה

מלכותם בכעותך בכלותיך לנער רשעים מארץ: לכן יכוממו במלכו רשמי —-

ישמחו השמים ותגל הארץ

ובכן מי לא יראך וגומר

I wrote down the notes in my facsimile copy of the Mahzor with a fountain pen using these transcriptions. This part of the Piyyut will survive.

I saw that the Artscroll Mahzor published a heavily censored element of the first paragraph in the back of the book, with the remaining Piyyutim (which avoids translating it into English, although it had been censored far too much to have posed a problem for them.) It appears truncated, because the other paragraphs of the Piyyut are consistently as long as the above quoted. For example, they write for stanza Daled : דבקיך דבוקים באלהים חיים, which poses grammatical and stylistic problems (eg. no other stanza is four words, it should’ve written דבוקיך, etc.) The stanza above reads: הגוים גדילים מעשיהו תעתוע דבקיך בדולים מסגרי לעץ בולים, which follows the ebb-and-flow, הגוים, and מי לא ייראך.

I also saw in the recently printed Mahzor h-Gra the same few stanzas as Artscroll are published, but also with confusions and clearly censored items.

Finally, this Mahzor contains an interesting addition to another Piyyut, that of היום תאמצינו. In this Mahzor, another stanza is added: היום תדרש דם עבדיך השפוך.

I conclude that among the treasures that have been found, that we find (or are waiting to be discovered) the history awaits in the elements that were in the full view of the public (Jewish and Christian alike) and the censored items, which wait to be discovered and to live new life.