Berakhot Koren Talmud Bavli and Ein Aya

Berakhot Koren Talmud Bavli and Ein Aya

by Chaim Katz

Berakhot Koren Talmud Bavli (KE) is a translation (into English) of Rav Adin Even-Yisrael Steinsaltz’s Hebrew edition of tractate Berakhot. It comprises the text of the Talmud, the in-line commentary, the explanation of foreign words, the mini-studies (iyunim), the biographies of selected sages, the description of cultural objects (hahayim), descriptions of fauna and flora and more. As far as I’ve noticed, they never mention in the front matter nor in the advertising blurbs that they added informational notes that don’t appear in the original edition, but there are more than 100 new notes in Berakhot KE.

In this paper, I’d like to present an overview of the new notes, and specifically examine the notes based on Ein Aya [1] – Rav Kook’s commentary to Ein Yaakov. [2]

I had a few questions about the notes based on Ein Ayah:

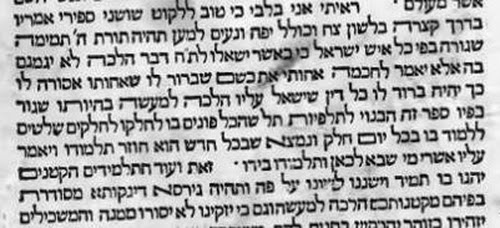

- In the Hebrew edition, Rav Adin created a bibliography of all the sources he used to compile his explanations. The list contains about 100 entries that stretch from Baal Halakhot Gedolot and Sheiltot (8th century) to Rabbi Akiba Eger (died 1837), the Hatam Sofer (died 1839), and commentaries printed in the Vilna Shas and the Vilna Ein Yaakov, e.g., Maharatz Chajes (died 1855), Rav Samuel Strashun (died 1872), Rav Hanokh Zundel the author of Etz Yosef (died 1867). Rav Adin did not incorporate any 20th century authors in his commentary. KE made an exception and included Rav Kook. What is the reason?

- Ein Aya is not really an explanation of Ein Yaakov. Rav Kook points out in its introduction that his work uses Ein Yaakov as a starting point. However, his goal was to expand the literature of Aggadah and produce a new type of reading material based upon ethical ideas in Jewish philosophy, kabbalah, musar and hassidut. Does KE realize that Ein Aya is not a commentary like the others?

- Ein Aya is very long. A haggadic statement that Maharsha devotes 15 lines of explanation to, is discussed by Rav Kook in about 60 lines (30 lines of double column text). How will KE summarize all that material? [3]

First, I’ll briefly review some of the new notes in KE and then examine a few passages quoted from Ein Aya. The following are new:

1 KE Daf 16b (page 112) has a biography of Rav Safra which is copied from the Hebrew edition Moed Kattan 25a

2 KE Daf 57b (page 371) has a biography of Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha copied from Gittin 58a

3 KE Daf 64a (page 409) has a note about the Chaldean astrologers, which is copied from the Hebrew Shabbat 156b.

4 KE Daf 17b (page 115) has a note about Jesus the Nazarene copied from the Hebrew Edition Sotah 47a.

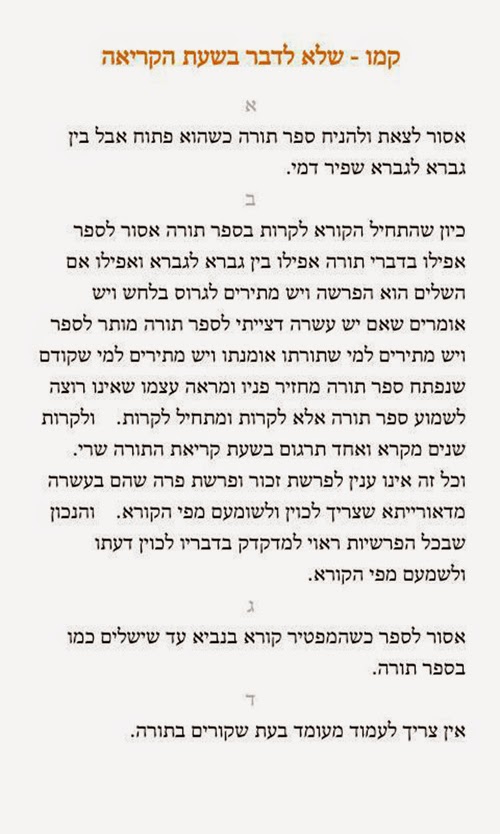

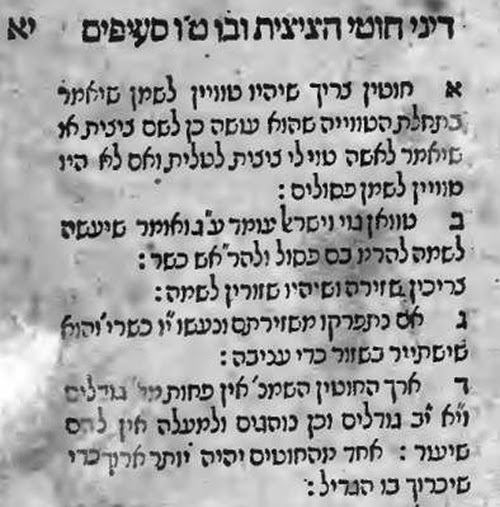

5 KE Daf 9b, (page 59) there is a note about tekhelet, similar but different from the notes in Menahot 38a .

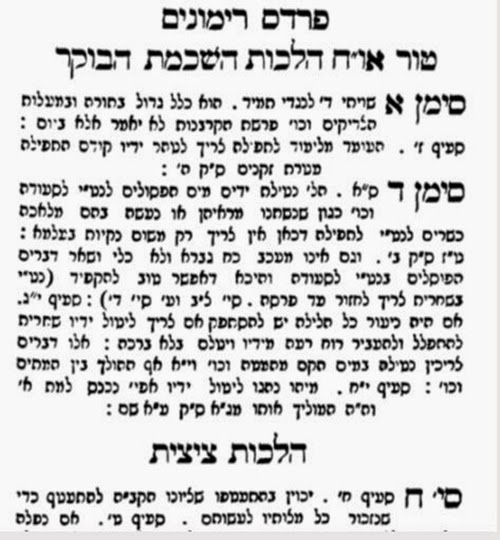

6 KE Daf 12b, (page 82) has a long note about tzizit – ritual fringes

7 KE Daf 13b, (page 91) there’s a definition of kavanah – intent

8 KE Daf 13b, (page 92) has a diagram of the placement of the tefillin on the arm and hand.

9 KE Daf 56b, (page 365) has a note describing a lion.

10 KE Daf 56b, (page 367) has a note describing an elephant.

11 KE Daf 41a, (page 270) has notes for: radish, olive, wheat, barley, and fig. The following page has a definition of a date.

12 KE Daf 59a (page 382) has a note about a rainbow.

13 KE Daf 7a, (page 42) has an unattributed explanation based on the words: “When I wanted you did not want . . . “. The explanation is from Maharsha.

14 KE Daf 10a, (page 64) has a comment concerning the relationship of the Holy One Blessed is He and the world. This explanation comes from Etz Yosef.

15 KE Daf 11b, (page 74) has an unattributed very long note about abounding love אהבה רבה and eternal love אהבת עולם. The note is taken verbatim from The Long Shorter Way (Chapter 4 – Two Ways of Loving G-d) [4].

16 KE Daf 51a, (page 323) has a clarification of a statement made by the angel Suriel. This is from the Maharsha.

17 KE Daf 58a, (page 374) has an explanation concerning the statement: “When Samaria was cursed, its neighbors were blessed”. The explanation comes from Anaf Yosef.

18 KE Daf 17a (page 114) There is a short note about the “Divine Presence” (although it’s not the first time that the word שכינה appears in the tractate.)

My sense is that the Steinsaltz Hebrew edition only introduces a note when there is a problem (on the page) that the additional note might solve. KE relaxes this constraint. I’ll illustrate this difference using the first example in the above list. We read in our Gemara:

After his prayer, Rav Safra would add: “May it be Your will, G-d our G-d, that You make peace among the members of the heavenly court…”

Rav Safra is one of many sages quoted. There is no problem that needs to be solved. The KE has a biography of Rav Safra that ends this way:

Since Rav Safra was an itinerant merchant, he never established his own yeshiva and did not spend much time in the study hall. Therefore, there were those among the Sages who held that he was unlike other Rabbis, that all are required to mourn their passing.

This is a strange piece of information which doesn’t look like it belongs in a biography. However, the Talmud Moed Kattan 25a, records the following discussion:

When R. Safra died, the students did not rend their clothes for him, since, they said, we have not learned from him. Abaye argued with them: Does the baraita say: ‘When a teacher dies’? Rather it says ‘when a scholar dies’. Moreover, every day in the study hall we discuss his interpretations of the halakha.

KE’s biography was copied from Rav Adin’s biography in Moed Katan.

There are many other examples of notes in KE that were copied from one location to another. They usually don’t fit very well in the destination location. In general, the notes regarding the religious objects add value. The notes describing the obvious (e.g., lion and elephant) are probably included for their esthetics.

Concerning Ein Aya: First, I’ll present the note, my translation and the Hebrew text of Ein Aya side by side and then I’ll discuss the note briefly.

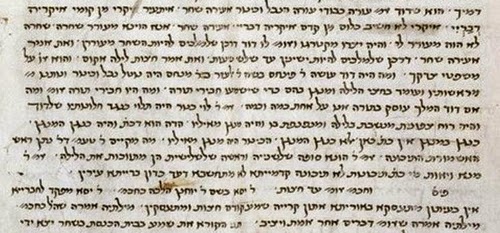

1 KE Daf 9a (Page 57), Ain Aya Berakhot 1 112

| When the children of Israel were redeemed from Egypt, they were redeemed only in the evening. And when they left, they left only during the day:

There are two separate elements to the transition from slavery to freedom. First, the slave acquires a personal sense of freedom and becomes master of his own fate. Second, he becomes free in the eyes of others, i.e., he is perceived by those surrounding him as a free man and has the potential to influence them. With regard to the children of Israel, the first element enabled them to receive the Torah and elevate themselves with the fulfillment of G-d’s commandments. The second element provided Israel with the opportunity to become a “light unto the nations.” Therefore, the redemption was divided into two stages. The first stage, in which they acquired private, personal freedom, took placed at night; the second stage, which drew the attention of the world to the miracle of the Exodus, took place during the day. |

R. Aba said: All agree that when Israel was redeemed from Egypt, they were redeemed specifically during the night, and when they left Egypt, they left specifically during the daytime.

Redemption from slavery to freedom in general has two effects on an entire nation: 1) An inner liberation and exaltedness that it senses when it exchanges the submissiveness of slavery for autonomy and self-determination. 2) A freedom to perform actions that impact the world. In Israel these two effects are more pronounced. For the inner freedom is the beginning of their own perfection – developing holy behaviors in Torah, its mitzvot and its wisdom. While the outer public freedom allows Israel to be a light to the nations. A great part of the latter mission has already been accomplished even in our time and will be fully completed when G-d has compassion on His nation. For from Zion will the Torah go forth (Is. 2:3), Even the people in the far-way lands will wait to hear Torah of Israel (Is. 42:4) Therefore, the redemptions are divided into two parts. When Israel was redeemed from Egypt – the inner redemption – this occurred during the nighttime. For the main point is not publicity or exposure to others, but a strong sense of their inner liberation. When they left, they specifically left during the daytime, publicly and openly for all the nations of the world to see, to demonstrate their worldly mission of instructing, benefiting and illuminating all of mankind with the light of G-d as it is written: Nations will walk in your light, kings in your glorious light. (Is. 60 3) |

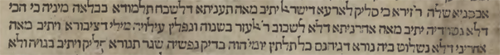

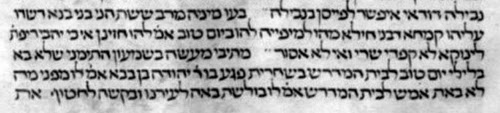

א”ר אבא הכל מודים כשנגאלו ישראל ממצרים לא נגאלו אלא בערב, וכשיצאו לא יצאו אלא ביום .

הגאולה מעבדות לחירות בכלל, פועלת בכלל עם-שלם שני עניינים. האחד הוא החופש שירגיש בנפשו התרוממות שיצא מכלל שפלות העבדות ונעשה בן חורין ואדון לעצמו. והשני הוא הפעולה הנגלית בעולם, בהיותו עם חפשי חי ופועל. ובישראל עוד יתר שאת לשני אלה, כי החופש הפנימי הוא התחלה לשלמות עצמם, בקדושת המדות בתורה ומצותי’ וחכמתה. והחופש הגלוי החיצוני, הוא עומד בישראל להיות לאור גויים, כאשר כבר נעשה חלק גדול מזה גם לעת כזאת, ויגמר בתכליתו לעת ירחם ד’ את עמו, כי מציון תורה תצא ולתורת ישראל איים ייחלון. ע”כ נחלקו הגאולות לשני חלקים, כשנגאלו ישראל ממצרים הגאולה הפנימית, היינו מבערב, שע”ז אין העיקר הידיעה והפרסום של זולתם, כי אם ההרגשה הטובה בחופשתם הפנימית. וכשיצאו לא יצאו אלא ביום, ביד רמה גלוי לכל יושבי תבל, להורות על פעולתם הגלויה בעולם, להשכיל להיטיב לכל ברואי בצלם להאיר באור ד’, כדבר שנאמר “וְהָלְכוּ גוֹיִם לְאוֹרֵךְ וּמְלָכִים לְנֹגַהּ זַרְחֵךְ |

KE skipped the nuance that Rav Kook was speaking about nations and not individuals. It also decided that redemption occurs in two stages, while Rav Kook only said that redemption has two components to it. They stopped short and didn’t capture the emphasis that Rav Kook placed on enlightening the nations (probably with the Noachide laws), but on the whole, it’s a fairly accurate summary.

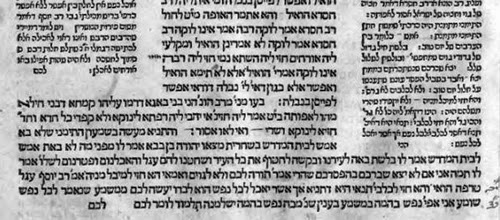

2 KE Daf 10b, (page 65), Ain Aya Berakhot 1 141

| From the chambers [kirot] of his heart – Often prayer is viewed as an act that combines the spiritual and the intellectual. There is a cognitive awareness of the necessity to turn to G-d in our time of need. When there is a pressing need, calling for a higher level of prayer, there can be an authentic call emanating from a person’s very heart, as the Psalmist declares: “My heart and my flesh sing for joy unto the living G-d” (Psalms 84:3) | Hezekiah turned his face to the wall and prayed. Why wall? Rabbi Shimon b Lakish said: From the walls of his heart.

There is a prayer that accompanies emotions that are intellectual, when the intellect perceives the value of the necessity of praying and recognizes the great worth of prayer. For the intellect is associated with the spirit of the heart, which resides in the chamber of the heart. However, when one fortifies oneself in prayer so much so that the body’s powers are aroused by the feelings generated by prayer, then the prayer affects the body, not just the soul. This is called praying from the walls of the heart. Namely, not just with the spirit, which is in the chamber of the heart, but also with physical vitality as it written: my heart and my flesh sing to the living G-d (Psalms 84:3) |

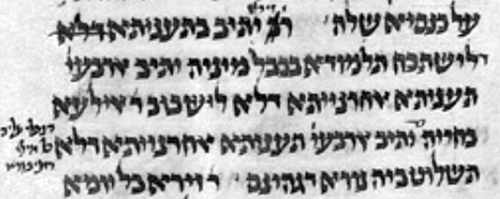

ויסב חזקי’ את פניו אל הקיר ויתפלל. מאי קיר ארשב”ל מקירות לבו

יש תפילה שבאה ברגש שכלי, שהשכל משקיף על ערך הנחיצות להתפלל ומכיר גדולת ערך התפילה. והנה השכל מיוחס לרוח הלב השורה בחלל הלב. אבל כשמגביר ברחמים עד שגם כוחות הגופניים מתפעלים מרגשי התפילה, ונמצא שהתפילה פועלת על הגוף לא על הנפש לבדה, נקרא שמתפלל מקירות הלב. כלומר לא מהרוח לבדו שהוא בחלל הלב, כ”א גם בהתפעלות בשרית, כמו שכתוב “לבי ובשרי ירננו אל אל חי”. |

This is a more difficult piece, particularly because we don’t relate to the view that (one side of) the heart is filled with spirit. We don’t identify with the description of the heart as a source of emotion and we no longer think of intellect affecting the flesh of the heart (but that’s another discussion).

The main problem with KE’s translation, is that Rav Kook is speaking here about the influence that prayer has on the person. He’s not speaking about “a higher level of prayer . . . an authentic call emanating from a person’s very heart”. He’s saying that a person can change himself through prayer. He can change his thoughts (chamber of the heart) and he can even change his character (walls of the heart). KE’s translation misses all of this. It misses the distinction between walls and chamber, and it misses the connection to the verse from Psalms that Rav Kook cites.

(It’s not the right place now to trace the history of the idea that the person refines and elevates himself through prayer. See maybe Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch on Devarim 11:13, or Rabbi Soloveitchik’s Shiurim l’Zecher Aba Mori z”l volume 2, page 29 and other places there.)

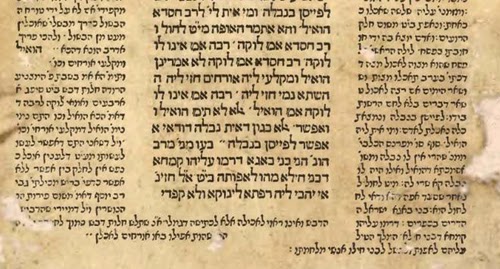

3 KE Daf 63b, (page 408), Ain Aya Berakhot 9 344

| Matters of Torah are only retained by one who kills himself over it [5]

While educators often try to make Torah study easier because they believe that doing so will lead students to accumulate more information and Torah knowledge, their approach is fundamentally flawed. The significance of Torah education is qualitative, not quantitative. It is not the sheer volume of knowledge amassed; it is the quality of the Torah wisdom that is attained. Simplistic, facile methods of study do not facilitate deep understanding. That can only be achieved through hard work and serious effort |

The school of R. Yannai taught: What is the meaning of (Mishle 30:33) The culturing of milk produces fermented milk (yogurt) … In whom do you find fermented milk of Torah, in the one who spits out the milk he nursed from his mother.

There are many educators who pride themselves for introducing methods that make learning simpler. They imagine they’ll benefit the world by transmitting lessons and knowledge of Torah in an undemanding way, eliminating the need to for a person to work. This assistance is misguided. Knowledge isn’t measured by quantity but by quality, according to depth and perceptiveness that enable the student to apply the knowledge to any situation. More so regarding Torah knowledge, which is measured by the profound impression on the student in his ethical personality, virtuous behavior, and pure fear of Heaven. Success will come when the studies do not follow an easy and undemanding curriculum. For through exertion and mental effort, a person is elevated to ethical behaviors, and turns with love and longing toward wisdom and holiness. The learning affects him such that he’s entirely dedicated and devoted to his lessons. Learning specifically with great effort produces a deep understanding, clarity in knowledge, and the pleasing way of serving G-d, fearing Him, and purifying one’s character. Studies that are acquired easily, without exertion and tremendous struggle will always be superficial, frozen and detached from the person’s inner soul. They will have minimal impact on his behavior and personality. Therefore, the fermented milk of Torah, the choice purified portion of Torah, the key aspect, clarified by deep thought and profound understanding that strengthens the soul in the fear G-d, and in the ways of holiness in whom will it be found? Only in one who was raised laboring in Torah and acquired Torah by following the beaten paths of strenuous effort and great toil; who distances himself from his childhood pleasures so that his Torah was not acquired though childish games. He spits out the sweet milk he nursed from his mother |

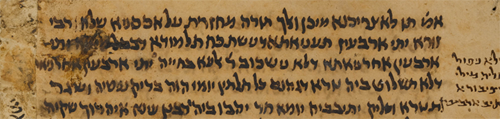

אמרי דבי ר”י: מאי דכתיב (משלי ל לג): “כי מיץ חלב יוציא חמאה במי אתה מוצא חמאה של תורה? – במי שמקיא חלב שינק משדי אמו עליה”

רבים הם הפדגוגים המתנשאים להביא דרכים להקל את עול הלימוד, וחושבים שיביאו ברכה לעולם בהקנותם את הידיעות והלימודים התורניים באופן קל, שלא יצטרך האדם להיות עמל בהם. תועלת הדבר אינה אמנם אלא מתעה, כי הידיעות לא תימדדנה על פי כמותם כי אם על פי איכותם, על פי עומק ההבנה וחריפות השימוש בהם לכל חפץ.ביותר לימודי התורה, על פי גודל הרושם שפועלים על הלומד, לענין התכונה של המוסר המעשים הטובים ויראת ה’ הטהורה. ובזאת יהיה מועיל רק הלימוד שאינו בא בדרכים קלים ונוחים לקלוט, כי על-ידי היגיעה ועבודה שכלית מתעלה האדם למידות נעלות, ולהיות נוטה אל השכל ואל כל דברי קודש באהבה וחפץ לב, והלימוד פועל עליו להיות כולו נתון ומסור ללימודיו. על-כן יצא מהלמוד שעל-ידי היגיעה דווקא, עומק ההבנה והידיעה הברורה עם הפעולה הרצויה לעבודת ה’ ויראתו וכל טהרת המדות. אבל הלימודים הנכנסים באופן קל, בלא יגיעה ועבודה כבירה, ישארו לעולם שטחיים וקפויים, עומדים מחוץ לנפשו של אדם הפנימית, ופועלים מעט על מעשיו ועל יצרי לבבו. ע”כ חמאה של תורה, הברור והמובחר שבה, העיקרי, המחוור בעומק רעיון ושום שכל והמרבה אומץ הנפש ביראת ה’ ודרכי קודש במי תמצא? רק במי שנתגדל על עבודת התורה בעמל, וקנה אותה בדרכים כבושים שע”י יגיעה ועבודה רבה, שעמדו לו להתרחק מן הילדות וכל געגועיה, לבלתי קנותם בדרך שעשועי ילדים, כ”א מקיא חלב שינק משדי אמו עליה |

KE, missed the point here as well. Rav Kook isn’t speaking about education or Torah education. It’s not about “deep understanding that can only be achieved through hard work and serious effort”

He’s speaking about love of G-d. The fermented milk of Torah represents the Torah studies that, under the proper conditions, lead the person to the love of G-d. Knowledge isn’t sufficient; one must labor and exert himself in these Torah studies and only then will they succeed in leading him to holiness.

(The basis of Rav Kook’s idea might be in the Sifre Devarim (on Deut. 6 6) quoted by Maimonides Book of Commandments, Positive #3, “You shall love G-d your G-d with all your heart’, can I know how to love G-d? The Torah therefore says: These words which I command you today shall be upon your heart. Thus, you will come to recognize the One who spoke and the world was created and you’ll cling to His ways.)

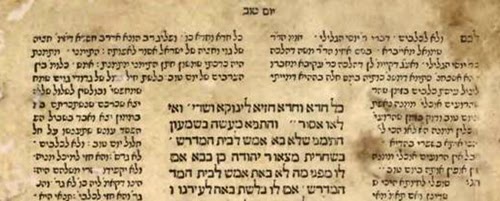

4 KE Daf 10a, (page 62), Ain Aya Berakhot 1 128

| David… resided in five worlds and said a song of praise corresponding to each of them:

There is a tremendous difference between looking upon an experience in a superficial manner and reflecting upon it and contemplating it. An individual who merely sees the external will not come to understand the deeper, spiritual significance of a given experience or encounter. Natural events like pregnancy, birth and nursing may seem to be mundane events experienced by humans and animals alike. However, one with a higher level of spiritual discernment will appreciate the vast difference between man and animal. King David’s songs of praise, uttered at every stage of life, attest to the magnitude of his sensitivity to G-d’s beneficence and to his appreciation of His role in the world. |

He lived inside his mother’s womb and offered songs of thanksgiving; he went out into the air of the world…

One who looks at the real world superficially cannot recognize the grandeur and beauty of the majesty of G-d nor the splendour of the human soul, as his perception of the real world is based exclusively on obvious visible traces of wisdom. In the words of the Duties of the Heart, (Hovot HaLevavot by Bahya ibn Pakuda Spain 11th century): based on the obvious visible traces of wisdom in the real world, both the intelligent man and the fool are equivalent. On the other hand, the truly gifted person will find hidden insights in the very things that didn’t inspire or elevate the person who looks at the world superficially. The truly gifted person will recognize the line of kindness that extends through all creations from their beginnings to their ultimate purpose. He will appreciate G-d’s wonders and thank Him. With happiness he will sing for G-d and for His goodness. He will recognize the majesty of his own soul that perceives the grandeur of the glorious King. Therefore, David (peace to him), who combined in himself depth of knowledge with sweet Divine song, sang about things that are discerned only with wisdom and deep contemplation. He lived inside his mother’s womb… Seemingly, there is no reason to be amazed. The experience is similar for a human or any other animal that doesn’t speak. In the womb, the human embryo is just like an amphibian or a lizard, the lowest rungs in the animal hierarchy. But when he reflects deeply, that in this lowly state all organs and limbs, which will serve the loftiest powers of the soul, are being completed. Not one is missing. If so, how great is the work taking place in the womb for the design of a person. Then, being so far from perfection, all the material and spiritual abilities he will later need are developing so that he’ll develop into a refined ethical person, who embraces in his brain and mind, the foundations of the world and its infinite expanses. |

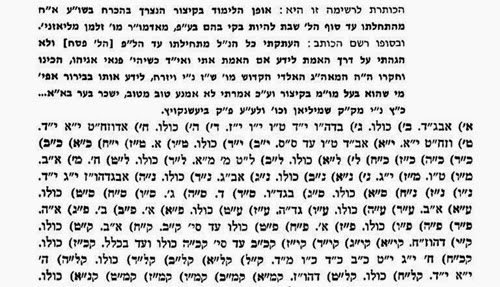

דר במעי אמו ואמר שירה, יצא לאויר העולם . . .

הבדל יש בין המסתכל רק בהשקפה שטחית על המציאות, הוא לא יוכל להכיר רוממות ה’ והדר גאונו ועם זה הוד נפש האדם, רק מהדברים הגלויים בסימני החכמה שבמציאות. כדברי חוה”ל, שבסימני החכמה הגלויים המשכיל והכסיל שוין בהם. אבל החכם האמיתי, הוא יחדור אל סימני החכמה הצפונים, שלעין הרואה רק חיצוניות הדברים לא יולד מהנה שום רוממות נפש. אבל החכם האמיתי, יכיר החוט של חסד ההולך בכל המעשים כולם מהתחלתם עד מטרתם, ויכיר נפלאות השם ית’ ויודה לשמו. ומטוב לב ישיר על ד’ ועל טובו, ויכיר הוד נפשו המכרת את הדרת מלך הכבוד. ע”כ דוד ע”ה שבו חובר עומק הדעת עם נועם השירה האלהית, אמר שירה על הדברים שרק בחכמה והשקפה רבה יוכר הודם ופלאם. דר במעי אמו, לפי החיצוניות אין להפליא כ”כ, מקרה האדם בזה כמו שאר החיים הבלתי מדברים, אז הוא במדרגת השרצים ג”כ שהם במדרגה הנמוכה של מערכת החי. אבל כשהתבונן, כי בהיותו במצב הנמוך הזה אז נגמרו ונוצרו כל יצוריו כולם, וכל האיברים המשמשים לכוחות הנפש היותר נשגבות אחד מהם לא נעדר. א”כ מה רבה התכונה הנעשה בבטן המלאה ביצירת האדם, שאז במצב רחוק משלמות והתפתחות כזה, צריכים שיוכנו לו כל הכוחות וכל הכלים הרוחניים והגשמיים שיצטרכו לו בהיותו אדם המעלה, המחבק זרועות עולם ומרחבי אין קץ בדעו ושכלו. |

Here too, I think, KE missed the point. It’s not about “the vast difference between man and animal”, which Rav Kook never mentioned. Rav Kook picks the theory of recapitulation to explain David’s song. According to the theory (which was immensely popular in the second half of the 19th century), the stages of embryonic development correspond to adult stages in the evolution of the species (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny). That’s why Rav Kook writes: the human embryo is then like an amphibian. But the theory is based on superficial similarities. The truly wise man looks beyond the superficiality and sees that each embryonic phase is not an evolutionary ancestor, but a point on a line extending from the person’s beginning to his birth. Each point on the line contains a hidden potential that will unfold and finally develop into a moral and ethical man. The insight (probably disproves the theory and) results in a greater appreciation of the Creator’s kindness, which is the song of praise that David sings.

We can now come back and answer the three questions that I posed earlier. 1) KE is not looking at Ein Aya as a typical commentary; that’s why they had no problem including Rav Kook’s words in the Berakhot volume. Additionally, I guess, the writers or editors have an admiration and affinity for Rav Kook and wanted to include some writings of his. 2) KE knows that in quoting a section from Ein Aya they are not explaining the text of the Talmud. Instead, they are attempting to follow the path of Ein Aya; to add thoughts and reading material of an ethical nature to KE. 3) It looks (at least in these few examples) that KE translated only the first few sentences of the Ein Aya section and then wrote up their own conclusions. They probably didn’t read to the end of the Ein Aya section(?), or if they did, they decided to “keep it simple”. I guess this can be excused too. In one of these notes they did write “see Ein Aya” instead of just attributing the section to Ein Aya.

Maybe the new notes in KE Berakhot aren’t of the same calibre as the original notes in the Hebrew edition. Still, they make the learning more interesting and more attractive. For this we should be thankful.

[1] Ein Aya is a work by Rav Kook on the Aggadah in Ein Yaakov, published by Makhon HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, Jerusalem. It consists of 4 volumes covering Berakhot and most of Shabbat. Though it was written over 100 years ago it was only published recently (approximately between 1995 and 2005). The text is also available at https://he.wikisource.org/wiki/

[2] Ein Yaakov is a collection of aggada from the Talmud Babli, by Rabbi Yaakov Ibn Habib (died 1516)

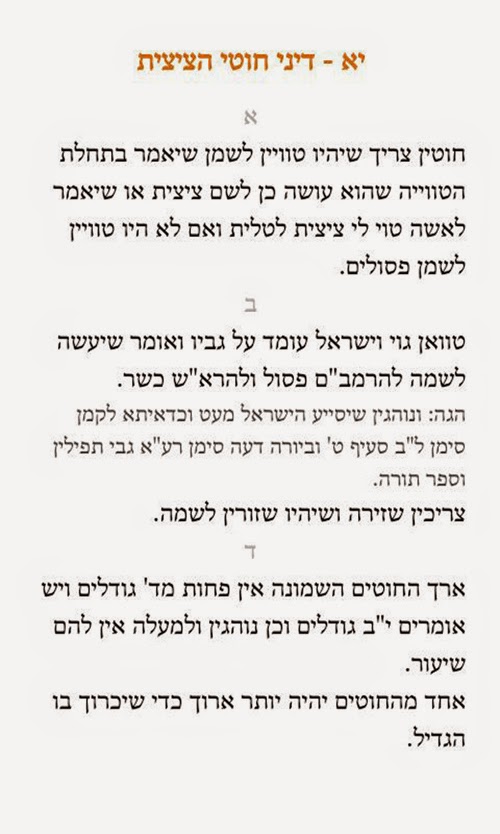

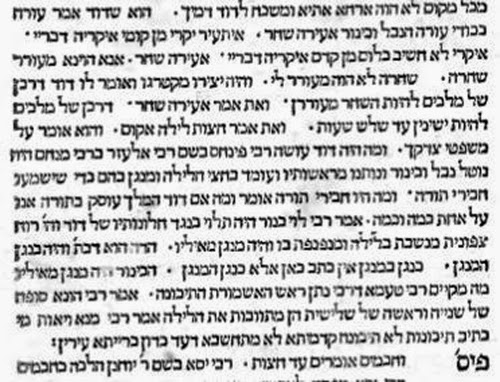

[3] I’m using as my example: Daf 3a “Rabbi Eliezer said: The night consists of three watches… during the first watch a donkey brays, during the second the dogs howl, during the third the infant nurses from its mother and a wife speaks with her husband”

[4] The Long Shorter Way, Discourses on Chasidic Thought, by Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, edited and translated by Yehuda Hanegbi, Koren/Maggid Publishers. Based on a series of lectures delivered by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz on Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi’s classic Chasidic work, the Tanya.

[5] There is a printing mistake here. They mixed up the passage’s key words (דיבור המתחיל) with another comment. I’m not sure if this mistake affected the subsequent translation.