Mississippi Fred McDowell, has

posted re: the Vilna Gaon’s Yerushalmi edition. However, I would like to discuss which edition of the Bavli the Vilna Gaon had. This is a rather important especially in light of the numerous emendations to the text the Vilna Gaon made. As when one is amending something it is important to know what exactly they have amended.

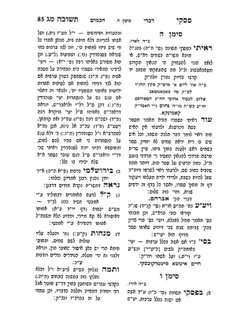

Every morning Birkat HaShahar are recited. Among these blessings are three anomalous ones. These there, as opposed to the rest, are in the negative. Specifically, these blessing are for ones legal status, gender, and religion. It is the last one, religion is the one we will focus on.

The Talmud has these blessing, however, there is some difficulty with the text of the religion one. Some editions have this blessing in the positive, i.e. “thank you for making me a Jew,” and some have it in the negative, “thank for not making me a non-Jew.” This confusion prevailed into the medieval period, with some texts containing one iteration of the blessing and some the other. What is unclear, however, is whether this change to the positive was wrought due to censorship or is there some reason this blessing should be in the positive.

R. Yom Tov Lipmann Heller, in his Ma’adani Melekh, claims any passage which is in the positive (“thank you for making me a Jew”) is due solely to censorship. And with this, we get to the crux of our discussion here – the Vilna Gaon’s edition of the Talmud.

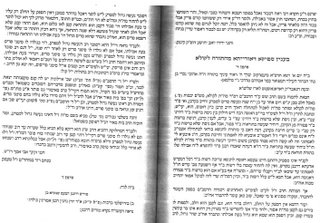

The Vilna Gaon, in his commentary on Shulhan Orach says that one should say this blessing in the positive form. He comes to this conclusion because “our editions of the Talmud have the blessing for ‘making me a Jew.'” In theory, the Vilna Gaon’s conclusion is dependent upon whether “our editions” are corrupted or not. That is, if “our editions” are censored then they prove nothing. This contention, that the Vilna Gaon used a corrupted edition is noted by R. Shmuel Feigenshon in the Otzar HaTefilot. Specifically, R. Feigenshon claims that had the Vilna Gaon seen the Amsterdam 1644 edition he would never made this mistake. [Additionally, based in part upon this, Y.S. Speigel notes the Vilna Gaon did not use manuscripts or earlier printed editions when he amended the text.]

It is worthwhile noting that R. Raphael Natan Rabinowich, in his Ma’amar ‘al HaDpasat haTalmud (which has just been reprinted by Mosad HaRav Kook) claims that the Vilna Gaon used the 1644 edition of the Talmud, the very one if he had used it would have avoid this error!!

In the end, we don’t know exactly which edition the Vilna Gaon used and according to Speigel, it is likely that the Vilna Gaon did not use one edition. Instead, it is likely the edition was dependent on the particular volume of the Talmud he had and for each volume it may have been a different edition.

Sources on the blessing: T.B. Menachot 43,b; Dikdukei Sofrim ad. loc.; Rosh, Berakot chapt. 9; Ma’dani Melekh id. at note 24; Tur Orakh Hayyimno. 46:4; id. Bach; Shulchan Orakh and Rama id.; see also, first edition of Rama Prague, 1588 for the proper placement of his comments available here; Biur HaGra id.; see also R. Y. Satnow, Va’yetar Yitzhak, no. 44; R. Jacob Emden, Luach Eres Toronto, p. 24 no. 64; Siddur Otzar haTeffilot, on the blessing in question; On the Vilna Gaon’s edition of the Talmud: Y.S. Speigel, Amudim b’Toldotha Sefer HaIvri: Haga’ot U’Magim, 404-405, 416 and the sources cited therein.