Marc B. Shapiro – Clarifications of Previous Posts

by Marc B. Shapiro

[The footnote numbers reflects the fact this is a continuation of this earlier post.]

1. I was asked to expand a bit on how I know that R. Barukh Epstein’s story with Rayna Batya is contrived. In this story we see her great love of Torah study and her difficulty in accepting a woman’s role in Judaism. Certainly, she must have been a very special woman, and I assume that she was, for a woman, quite learned. When Mekor Barukh was published there were still plenty of people alive who had known her and it would have been impossible to entirely fabricate her personality. The same can be said about Epstein’s report of the Netziv reading newspapers on Shabbat. This is not the sort of thing that could be made up. Let’s not forget that the Netziv’s widow, son (R. Meir Bar-Ilan) and many other family members and close students were alive, and Epstein knew that they would not have permitted any improper portrayal. It is when recording private conversations that one must always be wary of what Epstein reports.

A good deal has been written about the Rayna Batya story, and Dr. Don Seeman has referred to it as “the only record which has been preserved of a woman’s daily interactions with her male interlocutor over several months.”[15] When challenged about the historical accuracy of Epstein’s recollections, Seeman replied “that there is no evidence to indicate that R. Epstein invented these episodes out of whole cloth.”[16]

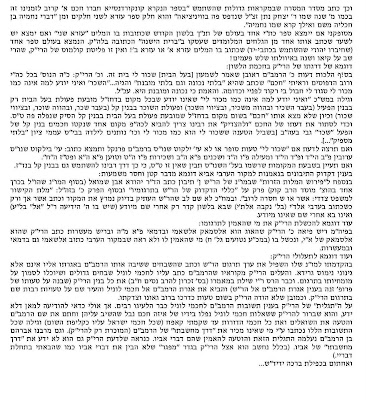

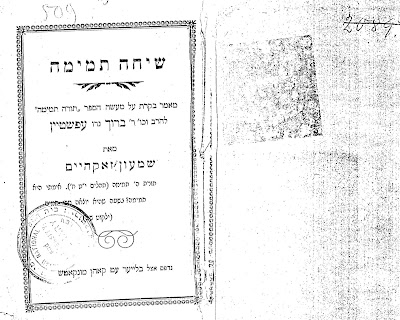

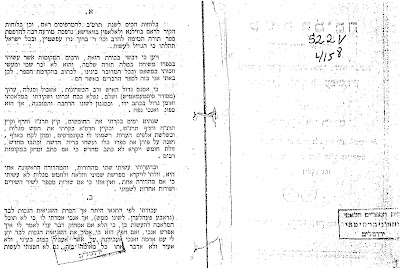

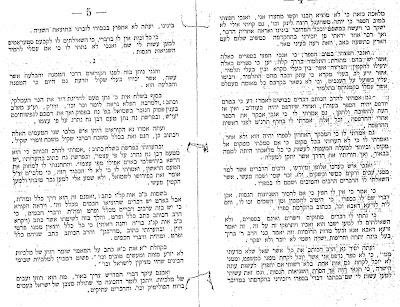

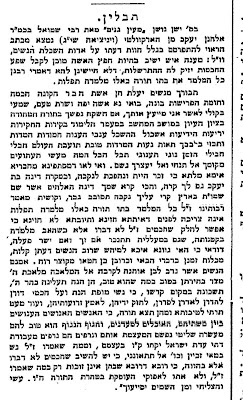

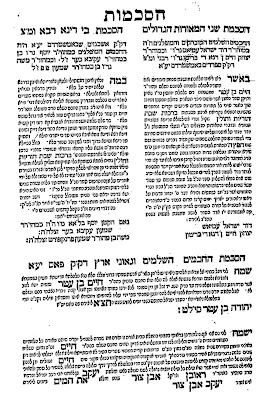

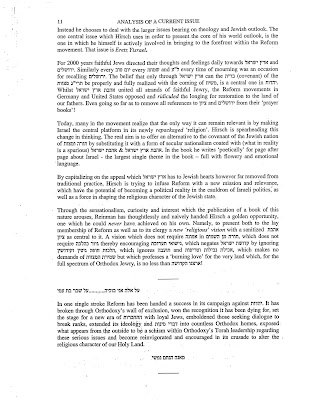

I will therefore explain how I concluded that the story is fictional. Let’s begin with the well-attested fact that Epstein was a plagiarizer. My assumption is that when dealing with someone who is not a reputable scholar, one must be very suspicious of what he or she writes when there is no outside evidence to back it up. In fact, when the Torah Temimah first appeared, the editor of this work published a booklet, Sihah Temimah, accusing Epstein of fraudulent behavior.[17] Here are the first few pages of this booklet.

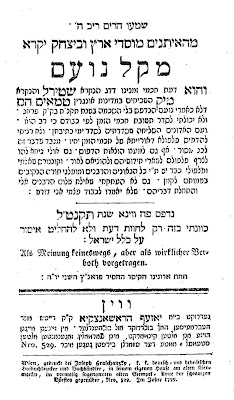

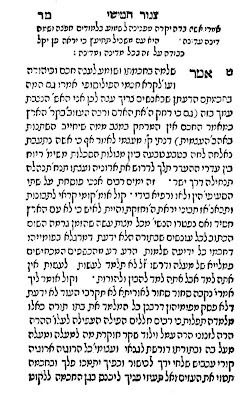

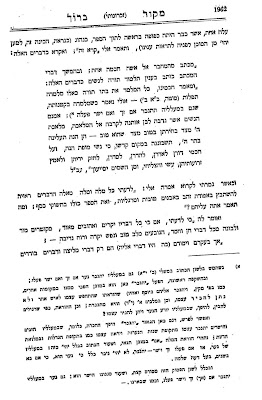

A central feature of his dialogue with Rayna Batya is her producing the book Ma’ayan Ganim by R. Samuel Archivolti. Here it states that mature women who have a desire to study Torah are to be encouraged (Mekor Barukh, p. 1962). Epstein, a young teenager, then attempts to refute her by arguing that the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim is not halakhic, but rather divrei melitzah. The whole dialogue, and in particular the part about her discovering the winning passage in Archivolti, is contrived and designed to lead the reader to sympathize with the fate of the poor woman.

A central feature of his dialogue with Rayna Batya is her producing the book Ma’ayan Ganim by R. Samuel Archivolti. Here it states that mature women who have a desire to study Torah are to be encouraged (Mekor Barukh, p. 1962). Epstein, a young teenager, then attempts to refute her by arguing that the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim is not halakhic, but rather divrei melitzah. The whole dialogue, and in particular the part about her discovering the winning passage in Archivolti, is contrived and designed to lead the reader to sympathize with the fate of the poor woman.

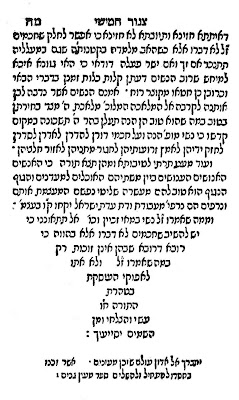

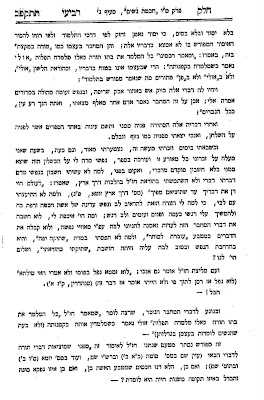

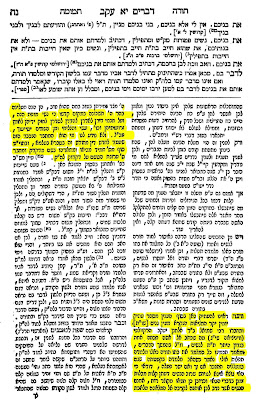

In his Torah Temimah (Deut. ch. 11 n. 68) he cites the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim that as a teenager he supposedly argued against. Anyone reading Torah Temimah would assume that Ma’ayan Ganim is a regular halakhic work, as Epstein refers to it as She’elot u-Teshuvot.[18]

Although at the end of the passage he says that he doesn’t know who the author is, and that Tosafot Yom Tov calls him a grammarian, I believe that this is all part of the literary game he is playing. In other words, he wants to publicize Archivolti’s view, and then to “cover” himself cites Tosafot Yom Tov. In Mekor Barukh, after telling his story, he points out that Archivolti was also a great talmudist and that the only reason the Tosafot Yom Tov refers to him as a medakdek was because he was referring to him in his youth.[19]

Dan Rabinowitz, in his discussion of the issue, writes:

The entire famous Rayna Batya incident must now be called into serious question. Was Rayna Batya so ignorant as to confuse Ma’ayan Gannim with a legitimate book of halakha? How, then, do we reconcile this with her supposed profound learning? It cannot be that R. Epstein was unable to recognize the Ma’ayan Gannim for what it was, for he himself writes that he told his aunt of the true nature of Ma’ayan Gannim. But if he did know what it was, how is it that in his Torah Temima he refers to Ma’ayan Gannim as responsa—and yet in the same paragraph in the Torah Temima he seems to backtrack and wonder how it is that the Ma’ayan Gannim could innovate “new laws about women with reason alone?” The entire Rayna Batya episode is a highly problematic one, raising one perplexing question after another.[20]

As far as the first few questions are concerned, I can only say that the entire report of Rayna Batya discovering the relevant text in Ma’ayan Ganim was made up by Epstein. This book, which was published in Venice in 1553, is an extremely rare volume. There would have only been a few copies of this book in all of Lithuania. (In Torah Temimah Epstein also says that it is a rare book.) It is therefore impossible to imagine that the rebbetzin, sitting in Volozhin, would just so happen to come across this volume on her husband’s bookshelf. Of this, there can be no doubt, and I assumed that Epstein, who was a great bibliophile, later in life came across the book and in his desire to publicize its contents, created the dialogue with Rayna Batya.

Yet thanks to R. Yehoshua Mondshine’s recent article,[21] I see that I was mistaken in my assumption. The truth is that Epstein never even saw the book and thus did not know the true nature of Ma’ayan Ganim. He learnt of the relevant passage, which he places in Rayna Batya’s mouth, from an article that appeared in Ha-Tzefirah, 7 Tishrei, 5656. We see this from the fact that the Ha-Tzefirah quotation mistakenly omits some words, and the same words are omitted in Mekor Barukh. This shows that his knowledge of this book came in 1894 and that he never discussed it with Rayna Batya, who died many years prior to this.

Now that we know where Epstein copied the text from, we can see another element of the literary game he played. He cites Ma’ayan Ganim as follows:

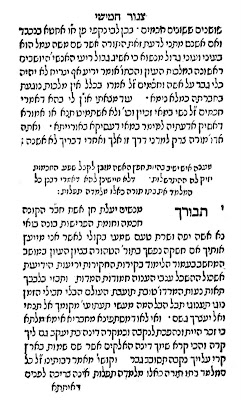

ומאמר חכמינו כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אולי נאמר כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Yet in Ha-Tzefirah it states:

מאמר רבותינו ז”ל כל המלמד בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אינה צריכה לפנים דאיתתא חזינא ותיובתא לא חזינא כי אפשר לחלק שחכמים ז”ל לא דברו אלא כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Leaving aside the words Epstein omits, he has substituted אולי for אפשר לחלק. In doing so he softened Archivolti’s point. Whereas Archivolti was stating that one can distinguish between teaching a grown woman and a small girl, Epstein has Archivolti prefacing this idea with “perhaps”. I think this is part of Epstein’s confusing game. He wants to bring this view to the public’s attention, but he doesn’t want to come off as too radical. In fact, this אולי, which is his own creation, assumes a life of its own. Thus, in his letter to R. Hayyim Hirschensohn (Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 6, p. 47), criticizing the latter’s view of teaching women Torah, Epstein writes:

In other words, Epstein invents the word אולי and inserts it into Archivolti’s letter, and then he uses this to criticize Hirschensohn! The chutzpah on Epstein’s part is astonishing, but as I see it this is all part of his game.

No one who has discussed Epstein and Rayna Batya was aware of his letter to Hirschensohn, so they could not point out the following obvious fact: When one looks at Mekor Barukh, which was published after his letter to Hirschensohn, one finds him telling Rayna Batya the exact same thing. It is obvious that he uses the language in his letter to Hirschensohn to create the following reply to Rayna Batya, that supposedly occurred some fifty years prior.

והן המחבר בעצמו כמו ‘מודה במקצת’ בזה, באמרו: ‘ומאמר חכמינו’ כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות ‘אולי נאמר כשמלמדה בקטנותה’; הרי שבעצמו אינו בטוח בדבריו, וכהוראת הלשון ‘אולי’ ולא ב”אולי” ולא ב”פן” מתירים מה שנאמר מפורש בתלמוד.

(It is possible that I am wrong in assuming that it was his positive view towards women studying Torah which explains why he created the story and cited Ma’ayan Ganim. Perhaps he was simply attempting to create a good story, or even some controversy, and that explains why he seems to be on both sides of the issue, as Dan Rabinowitz points out in the passage cited above.)

Here are the relevant pages in Ma’ayan Ganim, Ha-Tzefirah, Mekor Barukh, and Torah Temimah.

I know that there are people who are very upset at me, believing that I have given ammunition to those who chose to censor and withdraw My Uncle the Netziv. I make no apologies. We must combat falsehoods and plagiarism no matter where they emanate from. If, in the process, some of our own sacred cows are slaughtered, that is the price we must pay.

I know that there are people who are very upset at me, believing that I have given ammunition to those who chose to censor and withdraw My Uncle the Netziv. I make no apologies. We must combat falsehoods and plagiarism no matter where they emanate from. If, in the process, some of our own sacred cows are slaughtered, that is the price we must pay.

Returning to Mondshine, he is most concerned with the supposed dialogue between Epstein’s father, R. Yehiel Michel (the author of the Arukh ha-Shulhan), and the Tzemach Tzedek, R. Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. He sees it as an opportunity for Epstein to put all sorts of ideas, including criticisms of Hasidism, into the mouth of the great hasidic leader, something that if he did on his own would have brought down storms of criticism upon him. For example, he has the Tzemach Tzedek say that the hasidim have to be grateful for the opposition of the Vilna Gaon. Had it not been for the great dispute about Hasidism, and the Gaon’s strident opposition, the new movement might have led its followers out of the ranks of halakhic Judaism. (p. 1237). This idea was expressed by R. Kook (Ma’amrei ha-Re’iyah, p. 7) and was probably a common non-hasidic notion. But it is impossible to think that the Tzemach Tzedek would have ever expressed himself this way.

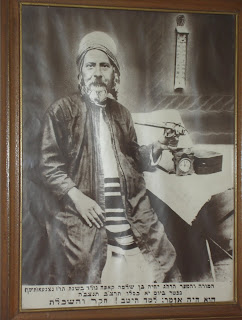

At the time that R. Yehiel Michel is said to have had his conversations with the Tzemach Tzedek, he was the rav of the Habad town Novozypkov.[22] In later years R. Abraham Chen and R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin served as rabbis of the town.[23] I know about this place because my grandmother’s second husband (who was like a grandfather to me) was from there. In fact, during World War One word came to the town that a certain group of Jews was being moved and would be passing through, and that among them was an outstanding young scholar named Shlomo Yosef Zevin. The townspeople came up with the necessary money to remove him from the group. He was chosen as the town’s rabbi and lived in my step-grandfather’s house for about six months. I read somewhere that the townspeople were followers of Kopys/Bobruisk, rather than Lubavitch. As R. Zevin was himself a Bobruisker, this would make sense. R. Yehiel Michel was himself born in Bobruisk, as was his son R. Baruch.

I always tell this story to Habad people in order to impress them with my yichus, that the great R. Zevin lived in my family’s house. Yet on two separate occasions after I told the story to young Habad shluchim, they replied, “Who is Rav Zevin?” It is also very rare to find a young Habadnik who has even heard of Kopust/Bobruisk. Yet without knowing about this it is impossible to understand how R. Zevin could have been a Zionist when the Lubavitcher rebbes were all anti-Zionist. After all, who ever heard of a hasid not following his Rebbe? The answer is that all Lubavitchers were Habad, but not all adherents of Habad were Lubavitch. The ignorance among some in Habad of their own movement probably shouldn’t surprise me, as I have met many hasidim who don’t have a clue about the history of the hasidic movement. And of course, how many Modern Orthodox know the first thing about Hirsch and Hildesheimer?

Mondshine assumes that one of the purposes of Epstein’s stories about his father and the Tzemach Tzedek is to build up his father’s halakhic reputation. His pesakim were subject to attack as being too liberal, and certainly in the hasidic world he was not accepted. In the Lithuanian world he was a much more important posek, and R. Joseph Elijah Henkin stated that in a dispute between the Mishneh Berurah and the Arukh ha-Shulhan, the Arukh ha-Shulhan is to be preferred.[24]

Yet many did not share R. Henkin’s viewpoint. A number of years ago I saw in one of R. Yitzhak Ratsaby’s books that he heard from some gedolim that one should not rely on the Arukh ha-Shulhan. I wrote to him objecting to this lack of respect for the Arukh ha-Shulhan, and also expressing my near certainty that the gedolim he referred to must have been Hungarian, for the Hungarian poskim never accepted the Arukh ha-Shulhan as an authoritative work. On Nov. 22, 1990, Ratsaby wrote to me:

בענין הגאון בעל ערוך השולחן, דוקא הדברים נובעים מליטא, והנני מפרש, הגר”י כהנמן זצ”ל מפוניביז’ (כמדומני שלמד בעצמו יחד עם הערוה”ש) והגר”ח גרינמן שליט”א בן אחותו של החזו”א. זכורני אמנם באגרות משה במקום אחד כתב על ערוה”ש כבר הורה זקן, ובמקום אחר דוחה דבריו. נראה לענ”ד אמנם שבעל ערוה”ש מחדש הרבה סברות ובזה כחו גדול, מאידך בעל משנ”ב מעמיק בעיון היטב הדק. והאמת ניתנה להיאמר שבהרבה מקומות בערוה”ש ראיתי דברים מתמיהים והיפך כוונת הדברים, וכבר הערתי עליו בדרך כלל במקומות שעסקתי בהם בחבורי הנדפסים. ופוק חזי שבישיבות לומדים בקביעות ההלכה מספר משנ”ב, וגם כמעט אין בית היום אשר אין שם משנ”ב. והחזו”א אעפ”י שחולק בהרבה מקומות על המשנ”ב, מ”מ החשיב אותו כהוראה מפי הסנהדרין ומנה אותו בנשימה אחת עם מרן הב”י והמג”א.

(Ratsaby’s recollection is correct. In Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim vol. 1 no. 39, which is his famous responsum on the proper height of a mehitzah, R. Moshe quotes the Arukh ha-Shulhan and uses the expression כבר הורה זקן. Regarding R. Joseph Kahaneman, he actually received semikhah from R. Yehiel Michel.)

The reputation of the Arukh ha-Shulhan has today fallen to such an extent that in a recent publication of the work the rulings of the Mishneh Berurah are included as well. The message of this is that while the Arukh ha-Shulhan is a Torah volume that should be studied, in terms of practical pesak it is the Mishnah Berurah that must be followed. See here for an earlier discussion at the Seforim blog of the recent reprint of the Arukh ha-Shulhan.

2. I was asked if there are any medieval poems in which there is explicit homosexuality. I am unaware of any, and it is precisely because they are ambiguous that there has been controversy about their meanings. This poem by Moses Ibn Ezra is as explicit as I could find

תאות לבבי ומחמד עיני

עופר לצדי וכוס בימיני

רבו מריבי ולא אשמעם

בוא הצבי, ואני אכניעם

וזמן יכלם ומות ירעם

בוא, הצבי, קום והבריאני

מצוף שפתך והשביעני

למה יניאון לבבי, למה

אם בעבור חטא ובגלל אשמה

אשגה ביפיך אד-ני שמה

אל יט לבבך בניב מענני

איש מעקשים, ובוא נסני

נפתה, וקמנו אלי בית אמו

ויט לעול סבלי את שכמו

לילה ויומם אני רק עמו

אפשט בגדיו ויפשיטני

אינק שפתיו וייניקני

כאשר לבבי בעיניו נפקד

גם עול פשעי בידו נשקד

דרש תנואות ואפו פקד

צעק באף, רב לך, עזבני

אל תהדפני ואל תתעני

אל תנף בי, צבי, עד כלה

הפלא רצונך, ידידי, הפלא

ונשק ידידך וחפצו מלא

אם יש בנפשך חיות, חיני

או חפצך להרג, הרגני

Desire of my heart and delight of my eyes –

A fawn beside me and a cup in my hand!

Many admonish me, but I do not heed;

Come, O gazelle, and I will subdue them. Time will destroy them and death shepherd them. Come, O gazelle, rise and feed me With the honey of your lips, and satisfy me.

Why do they hold back my heart, why? If because of sin and guilt, I will be ravished by your beauty – God is there! Pay no attention to the words of my oppressor, A perverse man – come and try me!

He was enticed and we went up to his mother’s house, And he gave his shoulder to my burden. Night and day I was only with him. I undressed him, and he undressed me; I sucked his lips and he sucked mine.

When I left my heart as a pledge in his eyes, The burden of my guilt was also weighted in his hand. He sought enmity, and inflicted his anger, And angrily cried, “Enough; leave me! Do not force me, and do not entice me.”

Do not be angry with me, gazelle, to destruction – Extraordinary is your will, my dear, extraordinary! Kiss your beloved and fulfill his desire. If it is in your soul to give life, revive me – Or if your desire is to kill, kill me![25]

3. When dealing with problematic texts of recent times, the preferred approach is simply to censor them. But with the medievals, there is a simpler method: Say that the text was written by a mistaken student, or even worse, by someone interested in undermining Judaism. In a previous post I mentioned that R. Joseph Zvi Duenner even stated so with regard to the Talmud itself.[26]

Since in modern times we don’t generally have students copying their master’s handwritten texts, the first approach doesn’t make much sense. Yet in a previous post at the Seforim blog,[27] I noted that R. Menasheh Klein used this very argument with regard to R. Moshe Feinstein, even though he was dealing with a responsum published in R. Moshe’s own lifetime. I found another example where Klein uses this exact same approach. He saw something in one of the Steipler’s books, but since it didn’t make sense to him, Klein wrote to the Steipler as follows (Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 7, p. 142a):

היות כי אני מכיר את מעכ”ק וצדקתו נגמר בדעתי שבודאי לא יצאו דברים מפי כ”ק או שיש שם איזה טעות בדפוס מהבחור הזעצער וטעה מעתיק ולא שם על לב כ”ק.

However, here I don’t think Klein should be taken literally. I believe this was just his respectful way of saying that the Steipler was wrong. This is not the case with regard to R. Ovadiah Yosef when he writes that one cannot rely on the responsa in R. Ben Zion Abba Shaul’s Or le-Tziyon, vol. 2.[28] Even though R. Ben Zion was alive, R. Ovadiah claimed that he was powerless to stop his students from taking liberties with the book: הוסיפו וגרעו כפי שעלה בדעתם, וסברו שכן דעת רבם. Not surprisingly, one of R. Ben Zion’s students responded very strongly to this statement.[29]

Prof. Yaakov Spiegel, in his book Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri: Ketivah ve-Ha’atakah, pp. 244ff., discusses the phenomenon of denying the authenticity of responsa. Sometimes the strategy used to reject a responsum is to attribute it to an “erring student.” While on occasion there are scholarly reasons for this assumption, it is almost always the case that the author simply cannot accept that an earlier authority said something. Usually this has to do with halakhah, but there are plenty of examples in theology. For example, R. Issachar Baer Eylenburg assumes that while resurrection is a principle of faith, one is not obligated to believe that this doctrine is found in the Torah. As he puts it (Be’er Sheva to Sanhedrin 90a).

מי שמודה ומאמין על פי הקבלה בתחית המתים אע”פ שהוא אומר דלא רמיזא באורייתא אין ראוי לקראו כופר חלילה ויש לו חלק לעוה”ב.

Although the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1, includes the point that one must believe that resurrection is found in the Torah, Eylenburg assumes that this is a textual error, and indeed, Rambam never mentions this. However, Rashi had this text and explains:

שכופר במדרשים דדרשינן בגמרא לקמן מנין לתחיית המתים מן התורה ואפילו יהא מודה ומאמין שיחיו המתים אלא דלא רמיזא באורייתא כופר הוא הואיל ועוקר שיש תחיית המתים מן התורה מה לנו ולאמונתו וכי מהיכן הוא יודע שכן הוא הלכך כופר גמור הוא.

Eylenberg didn’t like what Rashi said, i.e., it didn’t make sense to him, so he concluded:

לפי דעתי לא יצאו דברים אלו מפה קדוש רש”י אלא איזה תלמיד טועה פירש כן בגליון ונכתב בפנים.

Eylenberg would have been happy to learn what we now know, namely, that the commentary to Perek Helek is, in large measure, not really by Rashi.

I found another example of this in a book that just appeared, R. Menasheh Matloub Sutton’s Mateh Menasheh. (Sutton, who died in 1876, was the rav of Safed.) The second part of the book is a reprint of Sutton’s earlier published Kenesiah le-Shem Shamayim. This work is devoted to a superstitious practice whereby women would burn incense to demons and this was thought to be a help to people who were in various states of distress (e.g., sick, barren, etc.) He includes letters from many great rabbis who agree with him that this is a form of avodah zarah. The problem he has, which he confronts in ch. 2, is that one of the rishonim, R. Isaiah ben Elijah of Trani, is quoted by R. Hayyim Benveniste as follows:

ונראה בעיני המתוק שעושים הנשים מדבש וחלב לרפואה, וכן העישון שמעשנים מותר, שלא חייבה תורה בבעל אוב אע”פ שמקטר לשד אלא מפני שמעלה המת, וכן מעשה כשפים לא נאסרו אלא כשעושים מעשה או כשאוחזים את העיניים כמ”ש, אבל בעישון ומתוק אין בהם כל אלה, וגם אין בהם משום חובר חבר שאינם מתכונים לחבר השדים אלא לרצותם על רפואת החולה ושלא יזיקוהו.

Now it is certainly possible for Sutton to reject R. Isaiah, but it becomes very hard to label the practice as nothing less than idolatry when an outstanding rishon justified it and this rishon is also quoted by Benveniste and the Shiltei Giborim. What to do in such a case? Sutton adopts the tried and true method of declaring that since the position is (in his mind) so objectionable, R. Isaiah could never have said such a thing. It must originate with the “mistaken student” who often makes his appearance when a strange opinion is confronted.

אמינא בקושטא דמלתא כד ניים ושכיב רב אמרה להא שמעתא ועל הרוב שלא יצאו דברים הללו מתחת ידו וקולמוסו אלא שאיזה תלמיד טועה כתבם בגליון קונטריסו והרב שלטי הגבורים אגב ריהטא העתיקם בשמו ובחושבו דתורה דיליה היא מוצאת מעמו ולא פנה לעיין בעיקר הדין נמוקו וטעמו.

Sutton’s book was put out by one of his descendants, Rabbi Harold Sutton, who was a student in the late and much lamented Beit Midrash le-Torah (BMT) together with me. He later went on to become a student of R. Ovadiah Yosef, whose haskamah (together with that of R. Meir Mazuz) adorns the book.

Harold Sutton should not be confused with another young Syrian rabbi, David Sutton. The latter is the author of the ArtScroll book Aleppo: City of Scholars (and from the introduction I learned that he is a son-in-law of R. Nosson Scherman). Zvi Zohar has recently written a very sharp critique of this book. See here.

David Sutton is also the one who delivered the much-talked about lecture “We Believe in Midrashim.” This lecture is the subject of a very harsh attack by Roni Choueka in Hakirah 4 (2007). Choueka sees Sutton’s lecture as a bizayon ha-Torah of the worst sort. When listening to it I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry. How else is one to respond when one hears a rabbi claim that the fossils are remnants of the giant pets that belonged to Og, who was 800 feet tall and lifted up a stone the size of Manhattan, or that the polar bears came to Egypt complete with their blocks of snow in order to devour the Egyptian children?

Incidentally, in speaking of the Aggadah which describes the great height of Og, the Rashba (commentary to Berakhot 54b) notes that although there is a deep meaning conveyed in this Aggadah, the form in which it is expressed also had a very practical application:

לעתים היו החכמים דורשים ברבים ומאריכים בדברי תועלת והיו העם ישנים, וכדי לעוררם היו אומרים להם דברים זרים לבהלם ושיתעוררו משנתם.

In other words, in order to prevent people from dozing off, the Aggadist would convey his message with outlandish statements. R. Zvi Hirsch Chajes elaborates on this in his Introduction to the Talmud, ch. 26.

4. I have to thank those who have written to me calling my attention to things I did not know. I hope to acknowledge all of you at the proper time. However, many people who send me things have misinterpreted the sources (or the sources they send have been in error).

In the forward of H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver’s translation of Ibn Ezra to Deuteronomy, p. xiv, the following appears:

It should also be noted that I.E. [Ibn Ezra] was not the only medieval rabbi who believed that there are some glosses or slight changes in the text of the Torah. Thus Rabbi David Kimchi (c. 1160-1235) notes that the word Dan in Gen. 14:14 is post-Mosaic. He argues that the original reading of Gen. 14:14 was “and pursued as far as Leshem.” Rabbi Kimchi maintains that after the tribe of Dan conquered the city of Leshem and changed its name to Dan (Josh. 19:47), the reading of Gen. 14:14 was changed to read “and pursued as far as Dan” as in our texts of Scripture (Radak on Gen. 14:14).

The mention of “Dan” in Gen. 14:14 is used by all critical biblical scholars to prove that the verse must be post-Mosaic. The reason is that since the city would only be conquered in the days of Joshua, and only then be given the name Dan, how could the Torah refer to it this way? Even M. H. Segal, the strong defender of Mosaic authorship, acknowledges the problem. Unlike other scholars he assumes that the verse as a whole is Mosaic. But he also believes that the name “Dan” is a “modernized substitute for the antiquated names Laish or Leshem (Jud. viii, 29, Jos. xix, 47) which stood in the original.”[30]

Yet I was skeptical of what Strickman and Silver wrote as I was aware of Radak’s introduction to his Torah commentary where he is emphatic that the entire Torah is of Mosaic authorship.[31] I looked up Radak to Gen. 14:14 and saw that my skepticism was warranted. Here are Radak’s words:

וירדף עד דן: על שם סופו, כי כשכתב משה רבינו זה לא נקרא עדיין כן, אלא לשם היה נקרא וכשכבשוהו בני דן קראו לו דן בשם דן אביהם.

All Radak says is that the Torah refers to the place as Dan in anticipation of what it will be called in the future. Radak says nothing about the original reading of the Torah being “Leshem” and nothing about the text being changed after Leshem was conquered. As such, Radak cannot be added to the list of those who believe that there are post-Mosaic additions in the Torah.

5. In response to my earlier post at the Seforim blog discussing the meaning of ס”ט, Rabbi Yitzhak Oratz called my attention to Kitvei Ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan, pp. 50-51. In an 1892 letter from R. Yehiel Michel Epstein to R. Hayyim Hezekiah Medini, the author of the Sedei Hemed, we see that R. Yehiel Michel doesn’t know what the acronym stands for, as he writes חכם חיים חזקיאו [!] ס”ט הי”ו. Since the last two acronyms basically mean the same thing one would not put them next to each other, and he must have assumed that the first one meant sefaradi tahor. Yet by 1896 he had learned what it meant and he addresses the Sedei Hemed as מוהר”ר חכם חיים חזקיאו מודיני סופ”י טב טבא הוא וטבא ליהוי.

This is a rare example of an Ashkenazi who knows what the acronym means. For those who have not yet been convinced there is not much more I can say other than that there is a living tradition among the Sephardic scholars for hundreds of years now as to the proper meaning. This is certainly authoritative. Let me also call attention to the end of the introduction of the Peri Hadash on Yoreh Deah (found in the new Machon Yerushalayim edition). He signs his name as follows: חזקיה בן לא”א איש צדיק תמים היה בדורותיו דוד די סילוה נ”ע סופיה טב טבא הוא וטבא להוי אמן.

Also, see R. Yehudah ben Attar’s haskamah to R. Hayyim Ben Attar’s Hefetz Hashem (Amsterdam, 1732). R. Yehudah signs his own name סיל”ט. It is obvious that this is an alteration of ס”ט and means סופיה יהא לטב.  6. Some want to know if any of the letters Chaim Bloch published in Dovev Siftei Yeshenim are authentic. I haven’t carefully investigated every letter, so it is possible that a couple of them are also found in other books. If that is the case, then Bloch included them simply to give the work as a whole a sense of authenticity. There is, however, no doubt that everything that appears for the first time in the work is, in its entirety, a creation of Bloch. Interestingly, when Bloch sent the first volume to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe immediately recognized that the letters from the Rogochover were forged. He wrote to Bloch (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 69):

6. Some want to know if any of the letters Chaim Bloch published in Dovev Siftei Yeshenim are authentic. I haven’t carefully investigated every letter, so it is possible that a couple of them are also found in other books. If that is the case, then Bloch included them simply to give the work as a whole a sense of authenticity. There is, however, no doubt that everything that appears for the first time in the work is, in its entirety, a creation of Bloch. Interestingly, when Bloch sent the first volume to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe immediately recognized that the letters from the Rogochover were forged. He wrote to Bloch (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 69):

כן מאשר הנני קבלת הס’ “דובב שפתי ישנים”. ולאחרי בקשת סליחתו נצטערתי על שצויין על כמה מכ’ שהם להגאון הרגצובי – וכל הרגיל בסגנונו יראה תיכף שאינו . . .

The three dots are from the publisher, and I would be very interested to know what was taken out.

Bloch wrote to the Rebbe to defend his publication and the Rebbe responded very strongly. He tells Bloch that originally he thought that it was an innocent error or perhaps someone had misled Bloch as to the Rogochover’s letters. It now surprises him that Bloch continues to earnestly defend their authenticity. The Rebbe is so convinced that they are forgeries that he writes (Iggerot Kodesh, vol. 19, p. 159):

I assume that the Rebbe didn’t know that Bloch forged the letters himself, or that the rest of the collection was also forged. If he did know this, then I don’t think he would have been so polite to Bloch. He either wouldn’t have engaged in correspondence with him, or he would have told him that he is a liar and a scoundrel. Instead, after explaining why the Rogochover couldn’t have written the letters, the Rebbe concludes:

ואתו הסליחה על ביטוים אלו, שאולי אינם דיפלומטים ביותר.

One certainly doesn’t need to speak “diplomatically” to frauds, so I would assume that the Rebbe wasn’t aware of the extent of Bloch’s deception.

While on the topic of Bloch (who was previously mentioned at the Seforim blog [32]) I should note that his last Hebrew publication was Ve-Hayah Mahanekha Kadosh (New York 1965), which is directed against R. Moshe Feinstein’s permission for a married woman to be artificially inseminated from a non-Jewish donor. Bloch also wrote to R. Moshe about this, harshly rebuking him for this ruling. R. Moshe’s response (Iggerot Moshe, Even ha-Ezer vol. 2 no. 11) includes the following, which became one of the most famous passages in the Iggerot Moshe:

הנה קבלתי מכתבו הארוך מאד המלא דברי תוכחה על כל גדותיו על מה שלפי דעתו נדמה לו שתשובותי סימן י’ וסימן ע”א מספרי אגרות משה על אה”ע יגרמו איזה פרצה בטהרת וקדושת יחוס כלל ישראל. וניכר ממכתב כתר”ה שהיה סבור שיהיה לי קפידא על דברי התוכחה שלו, ואני אדרבה אני נרגש מזה שאני רואה שנמצאים אנשים בעלי רוח שאינם יראים ולא מתביישים מלומר תוכחה. אבל האמת שאין בדברים שכתבתי ושהוריתי שום דבר שיגרום ח”ו איזה חלול בטהרת וקדושת ישראל אלא תורת אמת מדברי רבותינו הראשונים, והערעור של כתר”ה על זה בא מהשקפות שבאים מידיעת דעות חיצוניות שמבלי משים משפיעים אף על גדולים בחכמה להבין מצות השי”ת בתוה”ק לפי אותן הדעות הנכזבות אשר מזה מתהפכים ח”ו האסור למותר והמותר לאסור וכמגלה פנים בתורה שלא כהלכה הוא, שיש בזה קפידא גדולה אף בדברים שהוא להחמיר כידוע מהדברים שהצדוקים מחמירים שעשו כמה תקנות להוציא מלבן. ואני ב”ה שאיני לא מהם ולא מהמונם וכל השקפתי הוא רק מידיעת התורה בלי שום תערובות מידיעות חיצוניות, שמשפטיה אמת בין שהוא להחמיר בין שהוא להקל. ואין הטעמים מהשקפות חיצוניות וסברות בדויות מהלב כלום אף אם להחמיר ולדמיון שהוא ליותר טהרה וקדושה.

7. Since I mentioned some stories from Halakhic Man that show that the Rav did not have a Modern Orthodox ethos, I will also say something about the following story, which some have wondered about.

Once my father entered the synagogue on Rosh Ha-Shanah, late in the afternoon, after the regular prayers were over, and found me reciting Psalms with the congregation. He took away my Psalm book and handed me a copy of the tractate Rosh Ha-Shanah. “If you wish to serve the Creator at this moment, better study the laws pertaining to the Festival.”

I understand that some people are very troubled by this story, as it bespeaks a real intellectual elitism. Yet, to use an expression popular among the younger generation, I can only say “get over it” (or become an adherent of one of the non-intellectual branches of Hasidism). For better or worse, traditional Judaism has always been a fundamentally elitist religion, dividing the haves (i.e., those who have knowledge) from the have-nots. (Although today we are accustomed to think in terms of bringing Torah study to all, in a future post at the Seforim blog I hope to mention some sources that speak of the danger of allowing the ignorant access to Torah knowledge.) Precisely because we have a notion of ein am ha-aretz hasid we can understand why, in contrast to Christianity, we don’t have women “saints” in our history. Since women have (until recent times) been kept ignorant of Talmud and halakhah, there was no way they could achieve any renown in the area of saintliness.

Regarding the passage from Halakhic Man quoted above, the Rav himself makes reference to R. Chaim of Volozhin’s Nefesh ha-Hayyim, and the ideology of that book is the basis for the Soloveitchik approach. In Nefesh ha-Hayyim 4:2 R. Chaim writes

הרי שהעסק בהלכות הש”ס בעיון ויגיעה הוא ענין יותר נעלה ואהוב לפניו יתברך מאמירת תהלים.

Yet I must also note that one needn’t be a Litvak to have this approach. Here is what R. Eliezer Papo writes (Pele Yoetz, s. v. yediah):

וכבר כתבו הפוסקים שמי שיוכל לפלפל בחכמה ולקנות ידיעה חדשה ומוציא הזמן בלימוד תהלים וזוהר וכדומה לגבי דידיה חשיב בטול תורה.

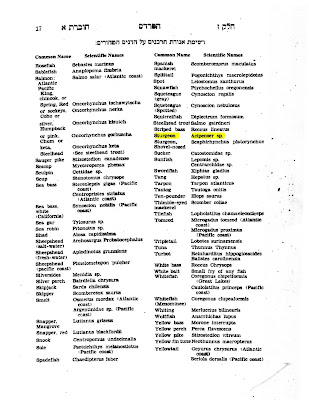

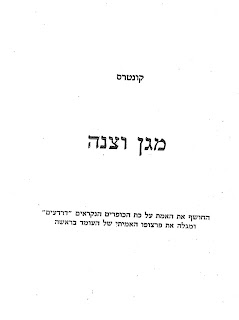

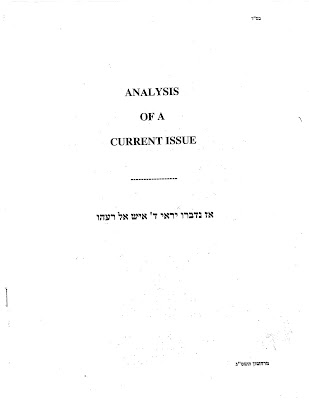

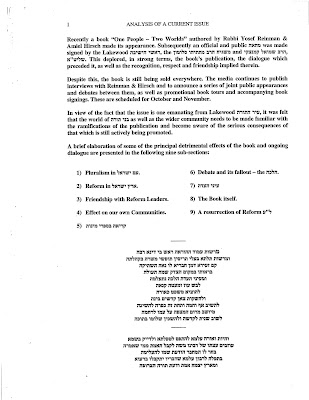

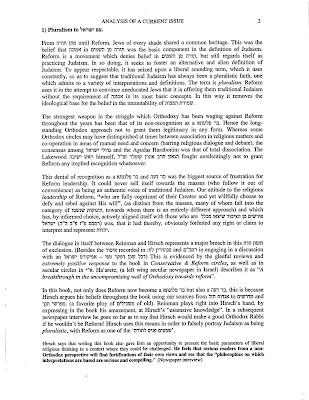

8. Many people have written to me about Ibn Ezra and post-Mosaic verses, a subject I dealt with in The Limits of Orthodox Theology. Let me therefore point out something in this regard that appears in One People, Two Worlds by Yosef Reinman and Ammiel Hirsch. As I am sure everyone recalls, this was the joint work by the Orthodox Reinman and the Reform Hirsch. What made this so significant is that Reinman is from Lakewood and never before had anyone from that community engaged in such a religious dialogue. The response was fast and furious, and here are the first three pages and the last page of an anonymous attack on him that appeared in Lakewood.

In fact, One People, Two Worlds is much worse – or much better, depending on your outlook – than anything done in this area by the Modern Orthodox. The Modern Orthodox who were part of organizations like the Synagogue Council of America and the N.Y. Board of Rabbis never engaged in interdenominational theological dialogue on an equal footing the way Reinman does. Furthermore, it is shocking that a haredi would have co-authored this book for another reason: What will happen if someone reads the book and is more convinced by the Reform rabbi? One would think that this would make the book a possible stumbling block.

In fact, One People, Two Worlds is much worse – or much better, depending on your outlook – than anything done in this area by the Modern Orthodox. The Modern Orthodox who were part of organizations like the Synagogue Council of America and the N.Y. Board of Rabbis never engaged in interdenominational theological dialogue on an equal footing the way Reinman does. Furthermore, it is shocking that a haredi would have co-authored this book for another reason: What will happen if someone reads the book and is more convinced by the Reform rabbi? One would think that this would make the book a possible stumbling block.

I have not read the book cover-to-cover, yet the word on the street is that the debate is pretty one-sided as the Reform rabbi is out of his league. But in glancing through the book I found that in one area it is actually the Reform rabbi who is correct. On p. 16 Hirsch refers to Ibn Ezra’s commentary to Gen. 12:6 and states that Ibn Ezra’s “secret” is a hint to his belief that the verse is post-Mosaic. On pp. 23-24 Reinman writes:

I do not understand how you can represent Ibn Ezra, the illustrious Orthodox commentator, as a closet Reformer. I personally have no idea of the nature of Ibn Ezra’s secret; he has successfully concealed it from me. But be that as it may, how can you ascribe non-Orthodox beliefs to Ibn Ezra? What about all the thousands of pages of solid Orthodox commentary he wrote? Don’t they stand for anything? You obviously need to connect to the time-hallowed texts, but you are grasping at the wind.

They go over this issue a couple of more times and Reinman’s responses are similarly dogmatic. Had Hirsch read my article on the Thirteen Principles (my book hadn’t yet appeared) he could have pointed out that plenty of “Orthodox” commentators and scholars have read Ibn Ezra exactly as Hirsch explained. In other words, it was incorrect for Reinman to respond as if Hirsch was asserting an outrageous canard against an “illustrious Orthodox commentator.”

When I saw this I asked a friend, who studied in Lakewood for many years, if is it possible that Reinman, who has been learning Torah for many decades, is completely ignorant about something that every YU student who takes Intro. to Bible learns in the first few weeks. His reply was that this is exactly the case, and that until he started reading works outside of the typical yeshiva curriculum he too never heard about an issue with Ibn Ezra and post-Mosaic additions. In fact, I would assume that R. Moshe Feinstein also never heard of it, and in his attack on the commentary of R. Yehudah he-Hasid he ironically cites Ibn Ezra condemnation of Yitzchaki’s biblical criticism. (Why Ibn Ezra would condemn Yitzchaki for suggesting that some verses are post-Mosaic, when he does that himself, is explained by R. Joseph Bonfils in his Tzafnat Paneah: Ibn Ezra was willing to accept individual verses as being post-Mosaic but not entire sections, which is what Yitzchaki is referring to. Thus, there is no Documentary Hypothesis in Ibn Ezra’s writings.)

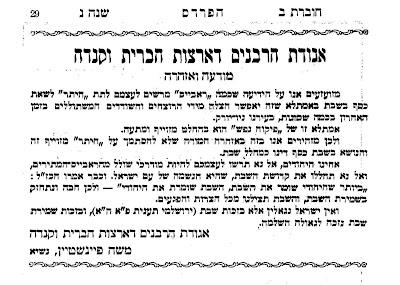

This phenomenon, of great scholars not being aware of things that most people reading the Seforim blog learned years ago, should not surprise us. The traditional yeshiva curriculum is very narrow, and you can spend your life in a yeshiva and unless motivated to expand your horizons, will have no knowledge of entire areas of Jewish thought and history. A good example[33] is seen in this announcement by Agudas ha-Rabbonim, which appeared in Ha-Pardes, November 1975.  Yet the beautiful saying which the learned rabbis assume was stated by Hazal was actually stated by Ahad ha-Am, and is perhaps his most famous saying (although the concept can be found in traditional sources, see Taz, Orah Hayyim 267:1)[34] However, for one whose only Jewish knowledge comes from the yeshiva, this information would be unknown, and it is easy to see how such a statement (“more than the Jews have kept the Sabbath the Sabbath has kept the Jews”) could “infiltrate” this closed world and become just another ma’amar hazal.[35] It reminds me of how when I was a kid and my friends and I went to Boro Park for Shabbatons we would have been able to hum niggunim which came from popular songs and commercials, and our hosts wouldn’t have known a thing. At the Rutgers Chabad house in the 1980’s they even had a niggun to the tune of the theme song for Bumble Bee tuna. For those too young to remember it, see it here.

Yet the beautiful saying which the learned rabbis assume was stated by Hazal was actually stated by Ahad ha-Am, and is perhaps his most famous saying (although the concept can be found in traditional sources, see Taz, Orah Hayyim 267:1)[34] However, for one whose only Jewish knowledge comes from the yeshiva, this information would be unknown, and it is easy to see how such a statement (“more than the Jews have kept the Sabbath the Sabbath has kept the Jews”) could “infiltrate” this closed world and become just another ma’amar hazal.[35] It reminds me of how when I was a kid and my friends and I went to Boro Park for Shabbatons we would have been able to hum niggunim which came from popular songs and commercials, and our hosts wouldn’t have known a thing. At the Rutgers Chabad house in the 1980’s they even had a niggun to the tune of the theme song for Bumble Bee tuna. For those too young to remember it, see it here.

Of course, Ahad ha-Am’s statement is sound Jewish doctrine, as should be expected from one who had a hasidic upbringing (he was born in Skvira). I don’t even think that the saying was original to him. Rather, he was repeating a hasidic idea that he heard in his youth. I say this because Rabbi Uri Topolosky – who is currently rebuilding Orthodox life in New Orleans[36] – called my attention to the following passage in the Sefat Emet to parashat Ki Tisa (from 1873; p. 198 in the standard edition):

ואך את שבתותי כו’ פי’ שלא להיות רצון ותשוקה לדבר אחר בעולם, רק להשי”ת שהוא שורש חיות האדם שתתדבק בו בשבת קודש . . . גם מה שמירה שייך לשבת אדרבה שבת שומר אותנו.

NOTES:

[15] “The Silence of Rayna Batya: Torah, Suffering, and Rabbi Barukh Epstein’s ‘Wisdom of Women.'” Torah u-Madda Journal 6 (1996): 127, n. 62.

[16] Torah u-Madda Journal 7 (1997): 197. Since I mention the fine scholar Don Seeman, let me also call attention to his article “Ethnographers, Rabbis, and Jewish Epistemology: The Case of the Ethiopian Jews,” Tradition 25 (1991): 13-29. In this article he deals with the issue I touched on in two earlier posts, namely, does “halakhic truth” need to correspond to what academics regard as “scholarly truth.”

[17] I thank Eliezer Brodt for calling it to my attention (it is not mentioned in Beit Eked Sefarim). Subsequently, I saw that it is mentioned by Yaakov Bazak, “Al Derekh Ketivat ‘Torah Temimah,’” Sinai 66 (1969): 97.

[18] Thus, R. Moshe Meiselman could write: “In the volume of responsa, Maayan Ganim, the author not only permits motivated women to study the Torah but praises them and urges his audience to encourage them in their work.” See Jewish Woman in Jewsh Law (New York, 1978), 38.

[19] R. Menahem Kirschbaum, Tziyun li-Menahem (New York, 1968), 263, points out that contrary to what Epstein states, Tosafot Tom Tov referred to him as a grammarian when Archivolti was quite old.

[20] “Rayna Batya and other Learned Women: A Reevaluation of Rabbi Barukh Halevi Epstein’s Sources,” Tradition 35 (2001): 61.

[21] See here

[22] See Kitvei ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan, part 2, p. 142, where he addresses someone as נכד איש אלקים גדול בעל התניא זי”ע ועל כל ישראל אמן. [23] See ibid., p. 154, for R Yehiel Michel’s 1906 letter of recommendation for R. Zevin. [24] See R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin, Beni Vanim, vol. 2, no. 8. In the introduction to Kitvei ha-Arukh ha-Shulhan one finds the following:

על מעמדו של הערוך השולחן כרבן של ישראל ופוסק הדור [שיש הסוברים שהוא הראשון במעלה ואחרון בזמן והלכה כמותו בכל מקום. עי’ בני בנים] אין כאן המקום להרחיב. What kind of reference is this? Most readers won’t even know what Bnei Vanim is. Why is the author, the volume, and page number not given? Why is R. Joseph Elijah Henkin’s name not mentioned? Furthermore, R. Henkin never said that the halakhah is always in accord with the Arukh ha-Shulhan. (Let’s not forget, the Arukh ha-Shulhan thought you could use electricity on Yom Tov.). His comment dealt only with the Arukh ha-Shulhan vs. the Mishneh Berurah.

For Eliezer Brodt’s review of this work, see here.

I have only skimmed part 2 of this important volume, but since it will probably be reprinted, let me make a few corrections and one addition.The transcription of R. Yehiel Michel’s handwriting on the first page is incorrect.

P. 79 s. v. והנה: The word הארוך should be האריך.

P. 146 s.v. גי”ק. The sentence reads: ורבות נצטערתי והמו מעי לו שירדפו גאון מובהק כמו”ב.

The abbreviation should be כמי”ב – כמותו ירבו בישראל. See p. 152, top line.

P. 173 no. 137: R. Aryeh Jacob Katznelson was the son-in-law of R. Yehiel Michel’s brother-in-law.

P. 193 n. 17: The quotation does not appear in no. 39.

According to Glick, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot he-Hadash, vol. 1 (Jerusalem and Ramat Gan, 2007), 582 (no. 2186), material from R. Yehiel Michel appears in R. Moses Spivak, Mateh Moshe (Warsaw, 1935).

[25] Hayyim Schirmann, Ha-Shirah ha-Ivrit bi-Sefarad u-ve-Provence (Jerusalem, 1954), vol. 1, no. 143; translation in Norman Roth, “‘Deal Gently with the Young Man’: Love of Boys in Medieval Hebrew Poetry of Spain,” Speculum 57:1 (1982): 45.

[26] See here.

[27] see my “Obituary: Professor Mordechai Breuer zt”l,” the Seforim blog (Monday, 11 June 2007), available here.

[28] See Yabia Omer, vol. 9, Orah Hayyim no. 108 (p. 269).

[29] See Shmuel Glick, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot he-Hadash, vol. 1 (Jerusalem and Ramat Gan, 2006), 57.

[30] The Pentateuch: Its Composition and Its Authorship (Jerusalem, 1967), 33.

[32] See here.

[33] See Avraham Korman, Ha-Tahor ve-ha-Mutar (Tel Aviv, 2000), 99.

[34] See Al Parashat ha-Derakhim, ch. 51, available here. The actual quote is

[35] R. Herzog was well aware of whose saying he was adapting when, in an article on Taharat ha-Mishpahah published in Ha-Pardes (September 1947, p. 15), he wrote:

[36] See here.