Responses to Comments and Elaborations of Previous Posts III

by Marc B. Shapiro

This post is dedicated to the memory of Rabbi Chaim Flom, late rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Ohr David in Jerusalem. I first met Rabbi Flom thirty years ago when he became my teacher at the Hebrew Youth Academy of Essex County (now known as the Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy; unfortunately, another one of my teachers from those years also passed away much too young, Rabbi Yaakov Appel). When he first started teaching he was known as Mr. Flom, because he hadn’t yet received semikhah (Actually, he had some sort of semikhah but he told me that he didn’t think it was adequate to be called “Rabbi” by the students.) He was only at the school a couple of years and then decided to move to Israel to open his yeshiva. I still remember his first parlor meeting which was held at my house. Rabbi Flom was a very special man. Just to give some idea of this, ten years after leaving the United States he was still in touch with many of the students and even attended our weddings. He would always call me when he came to the U.S. and was genuinely interested to hear about my family and what I was working on. He will be greatly missed.

1. In a

previous post I showed a picture of the hashgachah given by the OU to toilet bowl cleaner. This led to much discussion, and as I indicated, at a future time I hope to say more about the kashrut industry from a historical perspective.

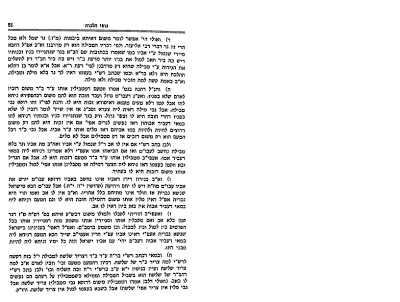

[1] I have to thank Stanley Emerson who sent me the following picture.

It is toilet bowl cleaner in Israel that also has a hashgachah. Until Stanley called my attention to this, I was bothered that the kashrut standards in the U.S. had surpassed those of Israel. I am happy to see that this is not the case. (In fact, only in Israel can one buy a package of lettuce with no less than six (!) different hashgachot. See

here)

But in all seriousness, I think we must all be happy at the high level of kashrut standards provided by the OU and the other organizations. This, of course, doesn’t mean that we have to be happy with what has been going on at Agriprocessors. I realize that this is a huge contract, but it was very disappointing to see that the first response of the OU to the numerous Agriprocessors scandals, beginning with the PETA video, has been to circle the wagons and put out the spin. Any changes from the OU only came after public outrage, and if the hashgachah is eventually removed from Agriprocessors, it will once again be due to this outrage. To be sure, we no longer can imagine cases of meat producers locking the mashgiach in the freezer,

[2] but it does seem that the company was being given pretty free reign in areas where the hashgachah could have been using more of its influence. (Let’s not forget that Agriprocessors needs the OU more than the reverse.) At the very least, we need some competition in the glatt kosher meat business. Agriprocessors has a near monopoly and as we all know, competition is what forces businesses to operate at a higher standard.

In fact, the entire glatt kosher “standard” should be done away with and turned into an option for those who wish to be stringent. This has recently been tried in Los Angeles, with the support of local rabbis, but I don’t know how successful it has been. The only way this can happen on a large scale is if the OU once again starts certifying non-glatt. The masses have been so brainwashed in the last twenty years that they will not eat regular kosher unless it has an OU hashgachah. There is no good reason – there are reasons, but they aren’t good – why the OU does not certify non-glatt. As is the case with the Chief Rabbinate in Israel, the OU should certify both mehadrin (glatt) and non-mehadrin.

It might be that people in Teaneck and the Five Towns don’t feel the bad economic times. Yet there are many people who are having difficulty making ends meet. It is simply not fair to create a system where people are being forced to pay more money for meat than they should have to. The biggest problem Orthodoxy faces, and the factor that makes it an impossible lifestyle for many who would otherwise be drawn to it, is the enormous costs entailed. Anything we can do to lower this burden, even if it is only a couple of hundred dollars a year–obviously significantly more for communal institutions–should be done.

Returning to Agriprocessors, while the current issue focuses on the treatment of workers, the problem of a couple of years ago focused on the treatment of animals. Yet the two should not necessarily be seen as so far apart. According to R. Joseph Ibn Caspi (Mishneh Kesef [Pressburg, 1905], vol. 1, p. 36), the reason the Torah forbids inflicting pain on animals is “because we humans are very close to them and we both have one father”! This outlook is surprising enough (and very un-Maimonidean), but then he continues with the following incredible statement: “We and the vegetables, such as the cabbage and the horseradish, are brothers, with one father”! He ties this in with the command not to cut down a fruit tree (Deut. 20:19), which is followed by the words כי האדם עץ השדה. This is usually understood as a question: “for is the tree of the field man [that it should be besieged of thee?] Yet Caspi understands it as a statement, and adds the following, which together with what I have already quoted from him will make the Jewish eco-crowd very happy.

כי האדם עץ השדה (דברים כ’ י”ט), כלומר שהאדם הוא עץ השדה שהוא מין אחד מסוג הצמח כאמרו כל הבשר חציר (ישעיה מ’ ו’) ואמרו רז”ל בני אדם כעשבי השדה (עירובין נד ע”א)

Finally, in Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld’s op-ed on Agriprocessors in the

New York Times (see

here) he wrote as follows: “Yisroel Salanter, the great 19th-century rabbi, is famously believed to have refused to certify a matzo factory as kosher on the grounds that the workers were being treated unfairly.” Herzfeld was attacked by people who claimed that there is no historical source to justify this statement. While the story has been garbled a bit, the substance indeed has a source. I refer to Dov Katz,

Tenuat ha-Mussar, vol. 1, p. 358. Here R. Yisrael Salanter is quoted as saying that when it comes to the production of matzah, one must not only be concerned with the halakhot of Pesah, but also with the halakhot of Hoshen Mishpat, i.e., that one must have concern for the well-being of the woman making the matzah.

אין כשרות המצות שלמה בהידוריהן שבהלכות פסח לבד, כי אם עם דקדוקיהן גם בדיני חשן משפט

2. In my

previous post I wrote: “With regard to false ascription of critical views vis-à-vis the Torah’s authorship, I should also mention that Abarbanel, Commentary to Numbers 21:1, accuses both Ibn Ezra and Nahmanides of believing that the beginning verses of this chapter are post-Mosaic. Yet Abarbanel must have been citing from memory, since neither of them say this. In fact, Ibn Ezra specifically rejects the notion that the verses were written by Joshua.” I made a similar point in

Limits of Orthodox Theology, p.106 n. 102.

I looked at Abarbanel again and would like to revise what I wrote. I don’t think it is correct to say that Abarbanel was citing from memory, since he quotes Nahmanides’ words. With regard to Ibn Ezra, I now assume that Abarbanel thinks Ibn Ezra is being coy. In other words, although Ibn Ezra cites a view held by “many” that Joshua wrote the beginning of Numbers 21, and then goes on to reject this view, Abarbanel doesn’t trust Ibn Ezra. He thinks that Ibn Ezra really accepts the “critical” view. I see absolutely no evidence for this. Ibn Ezra has ways to hint to us when he favors a critical view, and he never does so with this section. Furthermore, I am aware of no evidence that the “many” who hold the critical view are Karaites, as is alleged by Abarbanel.

What led Abarbanel to accuse Nahmanides of following Ibn Ezra in asserting that there are post-Mosaic verses in Numbers 21? As with Ibn Ezra, Abarbanel sees Nahmanides as hiding his critical view and only hinting to it. Numbers 21:3 reads: “And the Lord hearkened to the voice of Israel, and delivered up the Canaanites; and they utterly destroyed them and their cities; and the name of the place was called Hormah.” Yet as Nahmanides notes, it is in Judges 1:17 that we see the destruction of the Canaanites and the naming of the city Hormah. How, then, can the city be called Hormah in Deuteronomy when it won’t be conquered and named for many years?

Nahmanides writes that the Torah here is relating “that Israel also laid their cities waste when they came into the land of Canaan, after the death of Joshua, in order to fulfill the vow which they had made, and they called the name of the cities Hormah.” In other words, the Torah is describing an event, including the naming of a place, which will only take place a number of years later. This event is described in the book of Judges. The verse in Numbers is written in the past tense, which would seem to render Nahmanides’ understanding problematic. Yet as Chavel points out in his notes to his English edition, this does not concern Nahmanides. “Since there is no difference in time for God, it is written in the past tense, for past, present, and future are all the same to Him.”

This is certainly true with regard to God, but what about the Children of Israel? How are they supposed to read a section of the Torah that speaks about an event as having happened in the past but which in reality has not yet even taken place? These are problems that the traditional commentators deal with, but Abarbanel sees Nahmanides as departing from tradition and offering a heretical interpretation. He is led to this assumption because Nahmanides uses the ambiguous words “Scripture continued” and “Scripture, however, completed the account.” Why didn’t Nahmanides say that Moses wrote this? It must be, according to Abarbanel, that Nahmanides is hinting that this was written down after Moses’ death. In Abarbanel’s words:

כי הרב כסתה כלימה פניו לכתוב שיהושע כתב זה. והניח הדבר בסתם שהכתוב השלימו אבל לא זכר מי היה הכותב כיון שלא היה משה עליו השלום והדעת הזה בכללו לקחהו הראב”ע מדברי הקראים שבפירושי התורה אשר להם נמנו וגמרו שלא כתב זה מזה והרמב”ן נטה אחרי הראב”ע והתימה משלימות תורתו וקדושתו שיצא מפיו שיש בתורה דבר שלא כתב משה. והם אם כן בכלל כי דבר ה’ בזה.

From here, let me return for the third time to what some would see as an aspect of biblical criticism in Radak. To recap, in his commentary to I Sam. 4:1 Radak writes:

על האבן העזר: כמו הארון הברי’ והכותב אמר זה כי כשהיתה זאת המלחמה אבן נגף היתה ולא אבן עזר ועדיין לא נקראה אבן העזר כי על המלחמה האחרת שעשה שמואל עם פלשתים בין המצפה ובין השן שקרא אותה שמואל אבן העזר שעזרם האל יתברך באותה מלחמה אבל מה שנכתב הנה אבן העזר דברי הסופר הם וכן וירדף עד דן.

Dr. H. Norman Strickman convinced me that Radak means that the words “and pursued as far as Dan” are a later insertion, since the city was only named Dan after it was conquered in the days of Joshua (Joshua 19:47). In a comment to the post, Benny wrote:

There is no reason to assume that Radak is not referring to Moses prophetically writing the word Dan. It just means that in the time that the story took place, the name was not Dan. . . . I think that it is definitely possible that Radak understood that Moshe is the one who wrote “Et HaGilad Ad Dan”.

Dr. Yitzchak Berger wrote to me as follows:

I think the commenter ‘Benny’ was right about Radak’s view of Gen. 14:14. At I Sam 4:1 he’s probably merely contrasting the author-narrator’s [i.e. “sofer’s”–MS] perspective with that of the players in the story, concerning the phrases in both Samuel and Genesis (in the case in Samuel there would be no reason for him to introduce a later editor).”

As is often the case in these sorts of disputes, I find myself being moved by the last argument I hear. As I noted in the earlier post, Radak elsewhere insists on complete Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Thus, it is certainly easier to read this text in a way that would not create a contradiction.

While on the subject of Mosaic authorship, let me also add the following. David Singer recently wrote an interesting article on Rabbi Emanuel Rackman.

[3] With the recent passing of Rabbi Moses Mescheloff,

[4] Rackman, born in 1910, might be the oldest living musmach of RIETS. If this is so, don’t expect this to be acknowledged in any way by the powers at YU.

[5] The ideological winds have blown rightward in the last thirty years, and Rackman has moved leftward. He is thus no longer regarded as representative of RIETS or worthy of any acknowledgment.

[6]

A similar thing happened at Hebrew Theological College in Skokie. Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits (died 1992) was, in my opinion, the most significant and influential person ever to teach on its faculty. (Unfortunately, they didn’t let him teach Talmud, only philosophy.) Yet not only does HTC currently have no interest in recognizing him, in 2001, some eighteen years (!) after the appearance of

Not in Heaven, a very negative review appeared in the

Academic Journal of Hebrew Theological College.

[7] To show how insignificant Berkovits is in Skokie, neither the author, Rabbi Chaim Twerski, nor any of the editors, realized that his last name is not spelled Berkowitz! Were he alive today, can anyone imagine that HTC would allow him to speak? (It would be interesting to create a list of people who founded or taught at institutions and today would be persona non grata there. A few come to mind, and for now let me just mention R. Zev Gold, the outstanding Mizrachi leader who was one of the founders, and first president, of Yeshiva Torah Vodaas. Gold, who was also a rabbi in Scranton, was one of the signers of Israel’s declaration of independence.

[8])

Some people pointed out that in Twerski’s negative review, Berkovits is never even referred to as Rabbi, only as Dr. (A cynic might add that in his zeal to use the title “Dr.” instead of “Rabbi” for those he doesn’t approve of, Twerski even gives R. Judah Leib Maimon a doctorate, referring to him as Dr. Maimon.) In the following issue, Twerski apologizes for any disrespect, noting that while some people took offense at how he referred to Berkovits, others “who know [!] him well have told me that he always preferred to be addressed as ‘Dr. Berkovits.'” I think this is a fair response. After all, would anyone criticize an author for referring to “Dr. Lamm”? Yet I must also say that someone reading the article will not learn that Berkovits was a great talmudic scholar, and I don’t even know if Twerski recognizes this.

Returning to Singer, in his article he writes that Rackman accepted the Documentary Hypothesis. I discussed this issue with Rackman some years ago and this is definitely not what he told me. The most he would say was that he would not regard someone as a heretic if he accepted biblical criticism. Yet he personally was not a believer in the theory. In support of Singer’s assertion to the contrary, he quotes the following passage from Rackman: “The most definitive record of God’s encounters with man is contained in the Pentateuch. Much of it may have been written by people in different times, but at one point in history God not only made the people of Israel aware of his immediacy, but caused Moses to write the eternal evidence of the covenant between Him and His people.” He also quotes another statement by Rackman: “[T]he sanctity of the Pentateuch does not derive from God’s authorship of all of it, but rather from the fact that God’s is the final version. The final writing by Moses has the stamp of divinity – the kiss of immortality.”

Singer misunderstands Rackman. There is no Higher Criticism here, no Documentary Hypothesis. What Rackman is saying is that the stories in the Pentateuch might have been recorded by various people before Moses, but that these stories were later included in the Torah at God’s command, with Moses being the final author. In both of these passages Rackman is explicit that the Torah was written by Moses. Rackman’s position in these quotations is very traditional, asserting that all that appears in the Torah is Mosaic. With this conception it doesn’t matter if, for example, the stories of Noah or the Patriarchs had earlier written versions passed down among the Israelites, since what makes them holy and part of the Torah is God’s command to Moses that they be included in the Holy Book. This was done by Moses’ “final writing.” I can’t see anyone, even the most traditional, finding a problem in this.

While on the subject of Rackman, let me make a bibliographical point. R. Moshe Feinstein, Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Deah IV, no. 50:2 refers to:

המאמרים של רב אחד שמחשבים אותו לרב ארטאדקאקסי שנדפסו בעיתון שבשפת אנגלית . . . והנה ראינו שכולם דברי כפירה בתורה שבעל פה המסורה לנו.

R. Moshe goes on to further attack the heresy of this unnamed rabbi, who is none other than Rackman. This can be seen by examining Ha-Pardes, May 1973, p. 7, where R. Moshe’s letter first appeared. It is not a private communication but is described as coming from Agudat ha-Rabbonim of the United States and Canada, and R. Moshe signs as president of the organization. Earlier in this issue (it is the lead article) and also in the April 1973 Ha-Pardes, R. Simhah Elberg published his own attack on Rackman, referring to him as ראביי ר. Elberg refers to Rackman’s articles which appeared regularly in the American Examiner, and which so agitated the haredim – and also many of the centrist Orthodox. This paper then joined with the Jewish Week, and became known as the Jewish Week and American Examiner. Rackman continued to publish in the paper until around 2001. (His article discussing my biography of Weinberg was one of the last ones he would write, and it is reprinted in the second edition of One Man’s Judaism [Jerusalem, 2000], pp. 402-404.)

3. Many people were interested in the claim, quoted in an earlier post, that rabbis turned over their own children to become soldiers if these children were no longer observant. If something like this ever happened it would have been very heartless, and there were, of course, many children of gedolim who became non-religious. While in some cases the child choosing a different path led to estrangement with his father, in others, father and son remained close, and I think today everyone realizes that this is the only proper approach to take.

R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg thought that it might be a good idea for a father to attend his son’s intermarriage, in order not to break ties completely. (Believe it or not, this statement was published in

Yated Neeman.) Yet to see how different things were in years past, at least among some parts of our community, consider the following responsum by the important Hungarian posek, R. Jacob Tenenbaum.

[9] The case concerned an Orthodox shochet whose son went to the בית האון (This means the non-Orthodox rabbinical seminary in Budapest, against which the Orthodox rabbis carried on a crusade.) The problem was that during his vacations the son came home to his parents’ house. Tenenbaum was asked if this meant that the shochet was disqualified and could no longer serve the community. The father pleaded that he loved his son, and Tenenbaum replied that התנצלות זה הוא הבל. Tenenbaum also rejected the father’s claim that if he doesn’t show love to his son, the latter will go even further “off the derech.”

Tenenbaum demanded that the father make a complete break with his son (that is, if the father wanted to be regarded as a Jew in good standing). The choice was clear: The father had to decide between loving his son and making a living (for if chose the former he would be blacklisted throughout the country):

ואם אביו יתן לו מקום בביתו או יתמכהו באיזה דבר בזה יגלה דעתו שגם בו נזרקה מינות [!] ובזה אין חילוק בין שו”ב לאיש אחר . . . אם יחזיק ידו או יתן לו מקום בביתו הנה ידו במעל הזה אשר בנו פנה עורף לדת ה’ ועל כן צא טמא יאמר לו, ושלא יוסיף עוד ראות פניו אם לא ישמע לדבריו לעזוב דרך רשע.

I know this sounds like a Hungarian extremist approach, but R. Kook had basically the same viewpoint. In Da’at Kohen no. 7, he too is asked about a shochet whose non-religious sons live at home. R. Kook replies that while technically the actions of the sons do not destroy the hezkat kashrut of the father, nevertheless, the matter is very distasteful (מכוער). Even if the father could not be blamed at all in this matter, nevertheless, it is a hillul ha-shem. Since the beit din has the power to legislate in matters beyond the strict law, “there is no migdar milta greater than this.” He explains the reason for his uncompromising viewpoint:

שלא ילמדו אחרים להפקירות עוד יותר, כשרואין שבניו של השו”ב הקבוע הם מחללים ש”ק, ע”כ לע”ד ברור הדבר, שכ”ז שבניו הם סמוכין על שולחנו, ואין פוסקין מחילול ש”ק, איננו ראוי להיות שו”ב קבוע, ומה גם בעדה חרדית.

If this is said about a shochet, how much more would it apply to a rav of a community. It is therefore easy to understand why non-religious children of some well-known rabbis are no longer welcome in their parents’ home. (Other well-known rabbis have a completely different outlook, and reject what they would categorize as the conditional-love approach of Rabbis Tenenbaum and Kook).

4. Since I have mentioned R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg a few times, I must call attention to something that was pointed out to me by Rabbi Chaim Miller. Miller might be known to some readers for his wonderful editions of the Chumash and Haggadah with a commentary based on writings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. He has also published the first volume of a multi-volume work on the Thirteen Principles.

[10]

I have often been asked if Weinberg gave semikhah to the Lubavitcher Rebbe. There is such a story yet I always found it suspicious that it was never mentioned in the Rebbe’s lifetime. Furthermore, Weinberg never mentions this in his letters. (He does mention that R. Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn loved him.) So when asked, I always replied that I didn’t believe the story to be correct, as there is no evidence. In fact, I thought that the story was created as a clever way of giving the Rebbe semikhah. There is no record of him receiving semikhah before he arrived in Germany or after he left, so it made sense to have him receive it during his time in Berlin. Once you assume that the semikhah is received in Berlin, who better than Weinberg to give it to the Rebbe? Yet I always assumed that that this was a legend and wondered if the Rebbe even had semikhah.

Rabbi Miller called my attention to the new book,

Admorei Habad ve-Yahadut Germanyah, pp. 103ff., where R. Avraham Abba Weingort, who is completely trustworthy (and far removed from Habad), records the testimony of two other reliable people from Switzerland who knew Weinberg well. Although there is probably some exaggeration in the details of the story they tell, they report being told by Weinberg that he indeed gave semikhah to the Rebbe, and the circumstances of how this came about (including requiring that the Rebbe come to some of his shiurim at the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary).

[11] I can now better understand why the Rebbe’s contact information given to the University of Berlin was the address of the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary.

[12] From now on, whenever I am asked if the Rebbe received

semikhah from Weinberg, I will reply yes.

5. In recent years a few volumes from the writings of R. Yehudah Amital have been translated into English, allowing many new people to be exposed to his thoughts. Here is a provocative passage from his newest volume, Commitment and Complexity: Jewish Wisdom in an Age of Upheaval, p. 48:

We live in an era in which educated religious circles like to emphasize the centrality of Halakha, and commitment to it, in Judaism. I can say that in my youth in pre-Holocaust Hungary, I didn’t hear people talking all the time about “Halakha.” People conducted themselves In the tradition of their forefathers, and where any halakhic problems arose, they consulted a rabbi. Reliance on Halakha and unconditional commitment to it mean, for many people, a stable anchor whose purpose is to maintain the purity of Judaism, even within the modern world. To my mind, this excessive emphasis of Halakha has exacted a high cost. The impression created is that there is nothing in Torah but that which exists in Halakha, and that in any confrontation with the new problems that arise in modern society, answers should be sought exclusively in books of Halakha. Many of the fundamental values of the Torah which are based on the general commandments of “You shall be holy” (Vayikra 19:2) and “You shall do what is upright and good in the eyes of God” (Devarim 6:18), which were not given formal, operative formulation, have not only lost some of their status, but they have also lost their validity in the eyes of a public that regards itself as committed to Halakha.

This reminds me of the quip attributed to Heschel that unfortunately Orthodox Jews are not in awe of God, but in awe of the

Shulhan Arukh. In truth, Heschel’s point is good hasidic teaching, and R. Jacob Leiner of Izbica notes that one can even make idols out of mitzvot.

[13] He points out that the Second Commandment states that one is prohibited from making an image of what is in the heavens. R. Jacob claims that what the Torah refers to as being in the heavens is none other than the Sabbath. The Torah is telling us that we must not turn it into an idol. In this regard, R. Jacob cites the Talmud: “One does not revere the Sabbath but Him who ordered the observance of the Sabbath.”

[14]

I believe that the “halakho-centrism” that Amital criticizes has another pernicious influence, and that is the overpopulation of “halakhic” Jews who have been involved in all sorts of illegal activities. A major problem we have is that it is often the case that all sorts of halakhic justifications can be offered for these illegal activities. One whose only focus in on halakhah, without any interest in the broad ethical underpinnings of Judaism, and the Ramban’s conception of Kedoshim Tihyu, can entirely lose his bearings and turn into a “scoundrel with Torah license.” The Rav long ago commented that halakhah is the floor, not the ceiling. One starts with halakhah and moves up from there. Contrary to what so many feel today, halakhah, while required, is not all there is to being a Jew, and contrary to what so many Orthodox apologists claim, halakhah does not have “all the answers.” One of the most important themes in Weinberg’s writings is the fact that there are people in the Orthodox community who, while completely halakhic, are ethically challenged.

Since I already mentioned Rabbi Rakow, let me tell a story that illustrates this. I went to Gateshead to interview him about his relationship with Weinberg. When I got there I had a few hours until our meeting so I paid a visit to the local seforim store. I found a book I wanted and asked the owner how much it cost. He gave me a price, and then added that if I was a yeshiva student there was a discount. When I later met with Rakow I asked him if it would have been OK for me to ask one of the yeshiva students to buy the book at discount, and then I could pay him for it. He replied that there was certainly no halakhic problem involved. After all, the first student acquires the book through a kinyan and then I buy it from him. But he then added: “Yet it would not be ethical.”

Weinberg’s concerns in this area were not merely motivated by the distressing phenomenon of halakhically observant people who showed a lack of ethical sensitivity. His problem was much deeper in that he feared that this lack of sensitivity was tied into the halakhic system itself. In other words, he worried that halakhah, as generally practiced, sometimes led to a dulling of ethical sensitivity. Weinberg saw a way out of this for the enlightened souls, those who could walk the middle path between particularist and universal values. Yet in his darkest moments he despaired that the community as a whole could ever reach this point. This explains why he esteemed certain Reform and other non-Orthodox figures. Much like R. Kook saw the non-Orthodox as providing the necessary quality of physicality which was lacking among the Orthodox, Weinberg appreciated the refined nature of some of the non-Orthodox he knew and lamented that his own community was lacking in this area. It was precisely because of his own high standards that he had so little tolerance for ethical failures in the Orthodox community. Weinberg’s sentiments, which focused on inner-Orthodox behavior, were not motivated by fear of

hillul ha-shem. It was simply an issue of Jews living the way they are supposed to.

[15]

In his opposition to halakho-centrism, Amital finds a kindred spirit in R. Moses Samuel Glasner and cites the latter with regard to the following case. What should someone do if he has no food to eat, except non-kosher meat and human flesh. From a purely halakhic standpoint, eating non-kosher meat, which is a violation of a negative commandment, is worse than cannibalism. The latter is at most a violation of a positive commandment (Maimonides) or a rabbinic commandment according to others.

[16] Yet Glasner sees it as obvious that one should not eat the human flesh, even though this is what the “pure” halakhah would require, for there are larger values at stake and the technical halakhah is not the be-all and end-all of Torah.

[17]

Glasner writes as follows in his introduction to Dor Revi’i:

כל מה שנתקבל בעיני בני אדם הנאורים לתועבה, אפילו אינו מפורש בתורה לאיסור, העובר על זה גרע מן העובר על חוקי התורה . . . ועתה אמור נא, בחולה שיש בו סכנה ולפניו בשר בהמה נחורה או טרפה ובשר אדם, איזה בשר יאכל, הכי נאמר דיאכל בשר אדם שאין בו איסור תורה אע”פ שמחוק הנימוס שמקובל מכלל האנושי, כל האוכל או מאכיל בשר אדם מודח מלהיות נמנה בין האישים, ולא יאכל בשר שהתורה אסרו בלאו, היעלה על הדעת שאנו עם הנבחר עם חכם ונבון נעבור על חוק הנימוס כזה להינצל מאיסור תורה? אתמהה!

In other words, the Torah has an overarching ethos (Natural Law?) which is not expressed in any specific legal text, and this can sometimes trump explicit prohibitions.

[18]

Glasner has another example of this: Someone is in bed naked and a fire breaks out. He can’t get to his clothes and has two choices: He can run outside naked or put on some women’s clothes. The pure halakhic perspective would, according to Glasner, require him to go outside naked, since there is no biblical violation in this. But Glasner rejects this out of hand:

ובעיני פשוט הדבר דלצאת ערום עברה יותר גדולה . . . כי היא עברה המוסכמת אצל כל בעלי דעה, והעובר עליה יצא מכלל אדם הנברא בצלם אלוקים.

While I don’t know if the Rav would agree with Glasner, he too acknowledged that ethical concerns are a part of halakhic determination, meaning that not everything is “pure” halakhah. “Since the halakhic gesture is not to be abstracted from the person engaged in it, I cannot see how it is possible to divorce halakhic cognition from axiological premises or from an ethical motif.” Yet he adds: “Of course, in speaking of an ethical moment implied in halakhic thinking, I am referring to the unique halakhic ethos which is another facet of the halakhic logos.”

[19] I wonder, though, if the approach set out here stands in contradiction to how, in his famous essay, he portrays the Halakhic Man’s mode of thinking. Would Halakhic Man, whose values arise exclusively from the halakhic system, be able to write the following, which acknowledges a significant subjective element?

Before I begin the halakhic discussion of the subject matter I wish to make three relevant observations . . . I cannot lay claim to objectivity if the latter should signify the absence of axiological premises and a completely detached attitude. The halakhic inquiry, like any other cognitive theoretical performance, does not start out form the point of absolute zero as to sentimental attitudes and value judgments. There always exists in the mind of the researcher an ethico-axiological background against which the contours of the subject matter in question stand out more clearly. . . . Hence this investigation was also undertaken in a similar subjective mood. From the very outset I was prejudiced in favor of the project of the Rabbinical Council of America and I could not imagine any halakhic authority rendering a decision against it. My inquiry consisted only in translating a vague intuitive feeling into fixed terms of halakhic discursive thinking.

[20]

How often have I seen Orthodox polemicists criticize this very approach?

Finally, with regard to the issue of cannibalism mentioned above, let me point to one more relevant source (I can’t resist). In a previous post I mentioned that since every topic in halakhah has been dealt with in such detail, scholars today have to find new areas to focus on. Because of this, large books constantly appear about all sorts of things that are found in the sources, but to which no one ever gave much thought in previous years. The example I gave was an entire book dealing with the halakhot of sex change operations. The halakhot of cannibalism is one of the last areas which hasn’t yet been given a book-length treatment. However, R. Yosef Aryeh Lorincz has recently published

Pelaot Edotekha.

[21] The author is a rosh kollel whose previous book won an award from the municipality of Bnei Brak (see

here). He is also the son of Shlomo Lorincz, one of the elders of haredi politics. He raises the following question (before reading any further, make sure the digitalis is in easy reach): Is it permitted to eat the flesh and drink the blood of demons?! Let me quote some of what he says on the topic:

יש לעיין באותם השדים שיש להם דמות אדם ומתו מה דין בשרם ודמם האם אסורים באכילה, דפשוטו אינם אדם וגם אינם בהמה אלא בריה בפנ”ע ולא מצינו שאסרה תורה לבשר ודם דשדים, אולם להאמור לעיל דשד הוה מקצת אדם, א”כ הוה כעין חצי שעור ואסורים באכילה, עוד יש לעיין אם בשרו ודמו יש להם טומאה כמת עכו”ם, ואם אסורים בהנאה לשיטות דמת עכו”ם אסור בהנאה.

Whatever you may think about hashgachot on candles and toilet bowl cleaner, I am fairly certain that even if Lorincz can prove that demon’s flesh and blood is kosher, none of the kashrut organizations will be rushing to add their symbol to this product. But in all seriousness, I know that I am not the only one who thinks that it is very unfortunate that we have Torah scholars spending time on this sort of thing.

6. I have been asked to say something about the current conversion controversy. The halakhic problems will be sorted out by the poskim, but let me make a few comments about the historical issue. There have been a number of people who have stated that the lenient approach often associated with R. Uziel is a singular opinion, or that this view was original to him. That this is mistaken can be seen by anyone who examines Avi Sagi’s and Zvi Zohar’s book Giyur u-Zehut Yehudit. In fact, throughout most of Jewish history a lenient approach to conversion was the mainstream approach.

Now it is true that R. Herzog famously states that in earlier times one could be more lenient than today, because in a traditional society when someone converted he was immediately part of a community and was required to be observant.

[22] Things are very different today when you can convert and move to a secular neighborhood in Tel Aviv. There is no communal pressure for you to be observant, and the convert can look around and see that the leaders of the Jewish people in Israel, Peres, Olmert and Livni, are not religious. In such a world, R. Herzog didn’t think we could rely on certain leniencies used in the past.

However, despite R. Herzog’s opinion, the lenient approach, which didn’t insist on a convert’s complete observance of mitvot remained popular in modern times. (Contrary to what has often been stated, the lenient approach, and this includes R. Uziel, always insisted on

kabbalat mitzvot. The dispute concerns what “

kabbalat mitzvot” means, and whether a formal acceptance, without inner conviction, is sufficient.) Until recent years the lenient approach was even a mainstream position, alongside the more stringent (and widespread) approach. Among the adherents of the lenient approach one must mention R. David Zvi Hoffmann, who was the final halakhic authority in Germany until his death in 1921. Almost every Orthodox rabbi in that country, and many in other parts of Western Europe, looked to him as their authority. Others who held this position include R. Unterman and R. Goren. In addition, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate batei din, which were full of haredi dayanim, until recently followed the lenient approach. Many non-Jews were converted in Israel by dayanim who knew perfectly well that these people were not going to live an Orthodox life. Some of them were even intent on marrying people who were living on secular kibbutzim.

[23] No one ever challenged the validity of these conversions. The situation was similar in places outside of Israel. See R. Yitzhak Yaakov Weiss,

Minhat Yitzhak, vol. 6, no. 107:

לצערנו הרב גם רבנים חרדיים ומומחים מגיירים כעין זה ומחשיבים אותה כבדיעבד.

Unlike what goes on today, in previous generations there were never any classes for future converts. In fact, according to R. Akiva Eger, these classes are improper, since one is not permitted to teach Torah to a non-Jew.

[24] Now obviously, this is not the position we accept, but it does illustrate that in reality converts don’t need to know much about Judaism. R. Malkiel Zvi Tenenbaum writes similarly in dealing with a case from England where a man was with a non-Jewish woman and wanted to convert her. The man had stopped eating non-kosher and attended synagogue on Rosh ha-Shanah and Yom Kippur, but he was obviously not a completely observant Jew. Tenenbaum notes that even though it is possible that the only reason the woman is converting is so that she can remain with her husband–apparently she thought that this was in doubt due to his new religiosity– nevertheless, one should not be too exacting with her, other than telling her a few weighty and light mitzvot. This approach should be adopted because ex post facto the conversion will be fine, “and by doing this, we will save the Jew from living with her in a forbidden manner . . . but it is best that she learn everything [relating to Judaism] after she converts, and in particular in this case when we have to hurry to save the husband from sin.”

[25]

Even R. Moshe Feinstein’s opinion regarding conversion is not uniform, and you can see changes in his view in the direction of leniency. But leaving that aside, although R. Moshe requires real

kabbalat mitzvot, he acknowledges that a rejection of complete halakhic observance might not really be a rejection, because the person might not think that a particular law is really required. For example, what about a case where a woman converted in order to marry a Sabbath violator and was herself now a Sabbath violator? This is the exact sort of conversion that would be thrown out today. The fact that after the conversion she never observed Shabbat would suffice to show that there was no

kabbalat mitzvot. Yet R. Moshe disagrees. He says that it depends on the woman’s mindset. In this case, perhaps she never intended on violating the halakhah, but she didn’t believe that Shabbat is really a law! And why should she, when she sees that most Jews don’t keep it? In R. Moshe’s words, she thought that observing Shabbat was

hiddur be-alma, that is, something nice, but not required. This means that she never

rejected the halakhah of Shabbat, she just didn’t know about it, and people are not required to know every halakhah before they convert. Therefore, R. Moshe concludes that the conversion is valid.

[26] In another responsum,

[27] R. Moshe explains that even if one rejects a particular mitzvah of the Torah,

ex post facto the conversion is still valid:

ולכן צריך לומר שכיון שאיכא עכ”פ קבלת מצות אף שלא בכולן הוא גר ונתחייב בכולן אף שלא קבלם דהוה מתנה ע”מ שכתוב בתורה.

Anyone who reads responsa literature of the last hundred years often comes across cases where a man was intermarried and wanted to convert his wife, or wanted to convert his future wife. Often he had a child with the non-Jewish woman and wanted the child to be converted. A few different issues are discussed in these responsa, in particular

nitan al ha-shifhah, but one thing you find very little discussion of is

kabbalat mitzvot. The rabbis often give permission to convert the children even though the parents are not religious, and they give permission to convert the non-Jewish spouse even though there is no expectation that the person is going to lead a religious life. This obviously shows us that these rabbis had a different conception of conversion than what is today declared to be the only acceptable approach. Rabbi Yehudah Herzl Henkin

[28] has recently called attention to Rabbi Abraham Price’s comments in this regard.

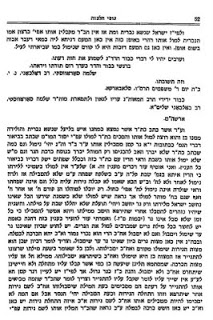

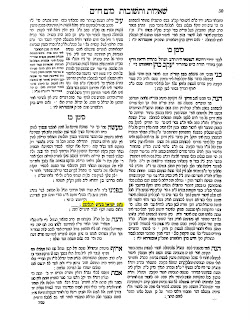

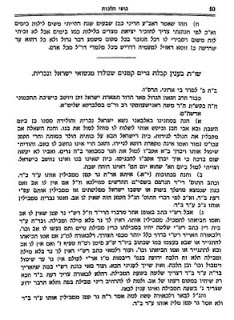

[29] Price was the leading rav in Toronto, and he defends the lenient approach (which was being carried out all over the world). Yet today, these conversions would be thrown out. Here is the page from Price’s sefer.

In the recently published responsa of R. Eliezer David Rabinowitz-Teomim (the Aderet), Ma’aneh Eliyahu, no. 65, he discusses converting a Gentile who was involved with a Jewish woman. He raises the issue of whether it is proper to convert the man if he will not be observant. Even though the woman will be spared the sin of intermarriage, the man who is converted will now be violating the prohbitions of Niddah and Shabbat. This means that he was in a better place before he converted, as he was not obligated in these laws. The Aderet never assumes that the conversion won’t be valid because the man will be non-observant. Indeed, his entire responsum is based on the fact that it will be valid, which leads him to wonder if conversions like this are a good idea.

אם הם מדור החדש, וקרוב הדבר שלא תשמור לטבול בזמנה, ויחללו שבת, ויכשלו באיסור נדה החמורה, רחמנא ליצלן, ועוד ועוד, באופן כזה חלילה, צריך ישוב והתבוננות אם לטובלו לדת ישראל.

(There are many other responsa where halakhists show great annoyance that people who convert often don’t live a religious life, but very few of these halakhists mention anything about the conversions not being valid.)

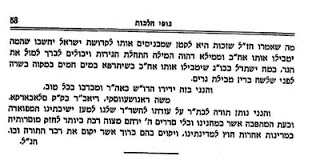

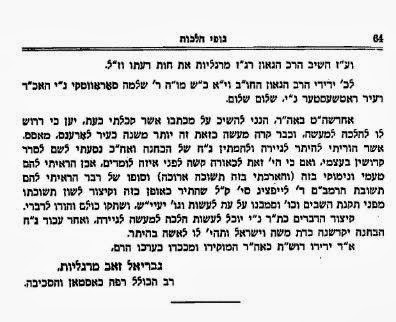

Here is another example that nicely illustrates what I am talking about. It has not been quoted in any of the numerous discussions of the issue and can be added to the lenient side. Yet as I indicated, there is nothing unusual in this case as the approach seen here was very popular. R. Shlomo Sadowsky was a rav in Rochester and in 1918 he published his sefer,

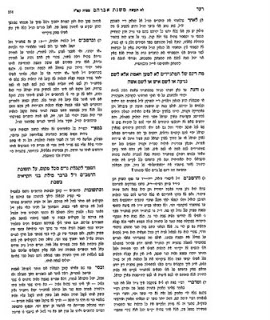

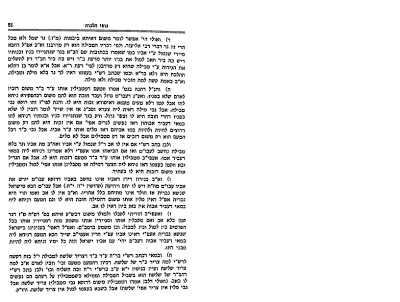

Parparaot le-Hokhmah. On page 63 he discusses converting a non-Jewish woman who is married to a Jewish man. In this case, he turned to R. Gavriel Zev Margulies, one of the leading poskim in America. (Joshua Hoffman wrote a wonderful masters dissertation on him.) The decision is made to convert her, and there is no mention of authentic acceptance of mitzvot. The halakhic concern focuses on a different matter, and the two rabbis are guided by the desire to help the man get out of the sin of intermarriage. Here is the responsum.

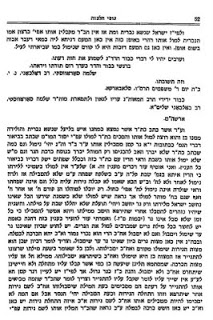

A few pages prior to this, Sadowsky has a responsum from 1906, when he was a rav in Albany. Here he discusses converting the son of a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother. The mother had no interest in converting. Sadowsky agrees to convert the child who would, of course, be raised in an intermarried home without any Torah or mitzvot. He sent his responsum to the great R. Moses Danishefsky, the rav of Slobodka, and Danishefsky agreed with him. There is absolutely no discussion about the fact that the boy will be brought up without Torah observance. Both Sadowsky and Danishefsky assume that there is a benefit to being Jewish, even if one is being brought up in an intermarried home.

[30] Here are the responsa from Rabbis Sadowsky and Danishefsky.

The technical issues are probably easier in this last case, as a child doesn’t need to have kabbalat mitzvot to be converted. Yet it is still significant that the issue of being raised in a non-religious home is not considered. There have been cases in Israel where the rabbinate refuses to convert children in situations like this, since the parents are not religious. The parents are thus forced to raise non-Jewish Hebrew speaking children, who of course will serve in the army and then marry Jewish Israelis.

For another example of converting women where there is no real expectation that they will be “observant” (by current standards), since their husbands were themselves not religious, see this responsum by R. Judah Leib Zirelson, from his Atzei ha-Levanon, no. 63.

I could cite a number of other sources, but it should be obvious by now that the lenient approach is hardly a

daat yahid, identified only with R. Uziel. I believe that an examination of the responsa literature reveals that until recently this was a mainstream approach among both rabbis doing conversions and poskim who dealt with this issue. I am not saying that it was the dominant approach, only that it was widespread. As we all know, however, many converts of years past would not be accepted by batei din today. (Nothing I have mentioned so far should imply that R. Druckman’s beit din followed any of the sources mentioned so far. From what I have been able to determine, his beit din required a lengthy instruction period as well as attachment to an Orthodox family during this period, and also complete acceptance of mitzvot. For one relevant article, see R. David Bass in

Tzohar 30, available

here.)

There is another important source, a pre-modern responsum that is not mentioned by Sagi and Zohar and is directly relevant to the issue of revoking of conversions. It is cited by the Shas member of Kenesset (and author of seforim), R. Hayyim Amselem,

[31] as part of his responsum against the revoking of any conversions. R. Simeon ben Tzemach Duran,

Tashbetz, vol. 3, no. 47, writes as follows:

מי שלא נתגייר אלא שעה אחת וחזר לסורו לאלתר ועבד ע”ז וחלל שבתות בפרהסיא כמנהגו קודם שנתגייר ומין הוא ומן המורדים הוא, דלא קרינן ביה אחיך כמ”ש למעלה, ואפ”ה חשבינן ליה ישראל משומד וקידושין קידושין . . . וכן ראיתי בתשובה למורי חמי הרב רבנו יונה שכתב כן, וכן כתוב בספר העיטור ובספר אבן העזר, שמעשה הי’ בכותי שקידש ואצרכוה גיטא מר רב יהודה ומר רב שמואל רישי כו’, והדבר ידוע שגזרו עליהם להיות כעכו”ם גמורים כדאיתא בפרקא קמא דחולין.

In other words, in a case where a convert immediately after the conversion practices idolatry and violates Shabbat, the rishonim mentioned hold that the conversion is valid and the person has the status of a sinning Jew. Today, we would be told that such a conversion is completely invalid, as it is obvious that the convert never intended to accept Judaism. The proof of this is that immediately following the conversion he continued in his old ways. Yet these rishonim hold that the conversion is binding.

R. Shlomo Daichovsky, until recently a dayan on the Supreme Rabbinic Court, held this position. Eight years ago he expressed his opinion against R. Avraham Sherman and wrote as follows:

[32]

נשותיהן של שלמה ושמשון עבדו עבודה זרה – כך מפורש בתנ”ך. גירותן היתה מפוקפקת מלכתחילה, כלשון הרמב”ם: ‘והדבר ידוע שלא חזרו אלו, אלא בשביל דבר’. בנוסף: ‘הוכיח סופן על תחילתן שהן עובדות עבודה זרה שלהן’. ועוד יותר: ‘לא על פי בית דין גיירום’. יש כאן שלושה חסרונות גדולים. אין לי ספק, כי אם היתה באה גירות כזאת לפני בית הדין ברחובות, היו פוסלים אותה, ללא כל בעיה. יתכן, וגם אני הייתי מצטרף לכך. אף על פי כן, רואה אותן הרמב”ם כישראליות לכל דבר. ומוסיף בהלכה י”ד: ‘אל יעלה על דעתך ששמשון המושיע את ישראל או שלמה מלך ישראל שנקרא ידיד ה’ נשאו נשים נכריות בגיותן’. כלומר, אסור להעלות על הדעת, אפשרות כזו. ובעצם, למה לא?

אין מנוס ממסקנה כי בדיעבד, אינו כלכתחילה. ולא ניתן לפסול גיור בדיעבד, לאחר שנעשתה.

R. Ovadiah Yosef believes that we can void a conversion, but only if there was (or should have been) a certainty before the conversion that the whole thing was a sham. But if there was no reason to think so, even if the convert did not become an observant Jew the conversion is valid. He writes (

Masa Ovadiah, p. 438

[33]):

“אם באמת היה הדבר גלוי וידוע מראש שאינם מקבלים עליהם עול תורה ומצוות, רק ע”ד האמור: ‘בפיו ובשפתיו כבדוני ולבו רחק ממני’, ואנן סהדי שלא נתכוונו מעולם לקיים המצוות בפועל, אז גם בדיעבד י”ל שאינם גרים. אבל אם לא היה כאן אומדנא דמוכח בשעת הגיור, אע”ג דלבסוף אתגלי בהתייהו, דינם כישראל מומר, שאע”פ שחטא ישראל הוא.

In the famous Seidman case, where R. Goren – based on R. David Zvi Hoffmann’s well-known responsum – converted a woman who was going to be living with a kohen after the conversion, R. Ovadiah agreed that the conversion was valid be-diavad. (See R. Shilo Rafael, “Giyur le-Lo Torah u-Mitzvot,” Torah she-Baal Peh 13 (1971), p. 131).

R. Yitzhak Yaakov Weiss was opposed to voiding conversions carried out by a valid beit din (Minhat Yitzhak, vol. 6, no. 107):

אם היה הגירות נעשה בפני בי”ד כשרים היינו מוכרחים לומר שהבי”ד בדקו היטב בשעת מעשה וראו שמקבלים בלב שלם, ע”כ אף שראינו שאח”כ אין מחזיקין במה שקבלו עליהם אמרינן דהדרו בהו ויש להם דין ישראל מומר

The rabbis at Kollel Eretz Hemdah were asked from Karlsruhe, Germany, about people who convert and continue to violate Shabbat and act no differently than before the conversion.

[34] In other words, they fooled the Beit Din. Are they to be regarded as converts? The reply is that while

le-hatkhilah one cannot convert people unless they accept to observe the Torah

אי-אפשר לבטל את הגירות של גרים שנתגיירו בבית-דין אורטודוקסי, אף על פי שלא היו כנים בבית-הדין ולא קיבלו על עצמם באמת לקיים את כל מצוות התורה, כל עוד שבאמת הם רוצים להיות יהודים, ורוצים להשתייך לעם ישראל.

As mentioned already, this is a matter that will have to be decided by the halakhic authorities. But I think that what I have written so far is sufficient to establish that there has been a great deal of distortion regarding this issue, often by well-meaning people. (In particular, I noticed that a number of writers, including talmidei hakhamim, have mistakenly claimed that the Bah is the only one to say that the Rambam didn’t require kabbalat mitzvot be-diavad.)

What is important to remember is that it is not just some modern Orthodox and religious Zionist rabbis who oppose the revoking of a conversion, but no less a figure than the Tashbetz. If today’s authorities disagree, that is their right, but it is simply wrong for haredi leaders to say that conversions have always required absolute commitment to mitzvah observance, and that lacking such commitment the conversions were always regarded as having no validity. As is often the case, there are different traditions. The adherents of the stricter approach are attempting to recreate the past, as if there has been only one approach. In fact, there is an even more radical view found in the rishonim. I refer to the Meiri’s position that

be-diavad one can convert without a beit din. That is, following circumcision one can then accept the Torah and immerse all by oneself, and

ex post facto it is a valid conversion.

[35]

I understand that all the discussions about the revoking of conversions have been very difficult for converts. After all, they were taught that once they convert they are as good as any other Jew. They have begun to learn that matters are not so simple. What is one of these converts supposed to think when they see the heading of R. Menasheh Klein’s responsum, Mishneh Halakhot vol. 9, no. 237: גרים כשרים אין להם יחוס וראוי לזרע ישראל לרחק מהם ?

He explains:

וודאי שיש מצוה לקרב ולאהוב את הגרים אבל אין זה מחייב להתחתן עמהם והרי משה רבינו קבל כמה גרים דכתיב וגם ערב רב עלה אתם ואפ”ה לא נתערבו בהם ולא התחתנו עמהם בני ישראל.

(By the way, the heading of the responsum following this is בענין נשים בעצם אם הם במדרגה אחת עם אנשים. Maybe on another occasion I will return to this, but I think everyone can predict what his conclusion is.)

This is a theme that is found in a number of his responsa.

[36] In fact, it appears that if he had his way there would be a complete ban on conversions.

[37] Since not every convert will be able to find another convert to marry, I guess he would advise having them marry the community’s losers, as no self-respecting Jew should marry a convert, at least not if you want your children to turn out right.

[38] As to why the children of converts don’t turn out properly, Klein has his own theory.

[39]

ודע דעלה בלבי מפני מה גרים לא יצליחו בניהם ע”פ רוב לפמ”ש דגר שנתגייר בידוע שנשמתו גם כן היתה מאותם שרצו לקבל התורה מסיני ולכן סופה שתתגייר, והנה כל זה נשמתו אבל נשמת זרעו שממשיך לא היו במעמד הר סיני ולכן אין זרעיו מצליחין . . . ומעתה מי פתי יסור הנה לישא אשה אשר יצאו ממנה בני סורר ומרה, ואם לפעמים ימצא שלא יצאו בדור הזה אולי עד עשרה דרי לא תבזה ארמאה ויחזרו ח”ו לסורם, ועכ”פ ע”פ רוב הכי הוא, והגע עצמך אם יאמרו לו שישא אשה חולנית שבעוד חמשה שנים תמות ורק על דרך נס יש אחת מיני אלף שתחיה או שע”פ רוב תלד בנים חולי גוף או רוח ודאי לא ישאנה . . . וכ”ש הכא שיצאו ממנו ח”ו דורות כאלו וכיוצא בה, מי הוא בעל אחריות שייעץ לאדם לישא אשה כזו.

He then quotes some negative things said about converts in the Zohar, and concludes as follows, in words that the Eternal Jewish Family

[40] will never include in its literature and which are very hurtful:

ומעתה מי זה יכול ליעץ לאדם מישראל אשר נתחייבנו עליו ואהבת לרעך כמוך ואמרו ז”ל מה דסני לך לחברך לא תעבד והאיך נעבור על יעצנו רע ח”ו לזרע קודש משרשא קדישא וגזעא דקשוט להתערב ולתתגעל בגיורת המזוהמה בזוהמת הנחש . . . ולכן ודאי דכל מי שחש וחס על עצמו ועל זרעו יראה להדבק בטובים.

It is interesting that R. Moshe Sternbuch expresses the exact opposite approach to converts.

[41] We can see the same sort of dispute between them with regard to baalei teshuvah, with Klein having a suspicious and at times negative view toward them, and Sternbuch having the opposite approach. But before one assumes that Klein’s outlook is just another example of the far-out positions he often takes, take a look at the following from R. Kook,

[42] commenting on

Berakhot 8a which states: “Some say it means: Do not marry a proselyte woman”:

כי ראוי לדאוג שיהיו תולדותיו זרע ברך ד’ בטבעם קשורים ג”כ בקשר טבעי עם ד’. אבל הגיורת, קשורה אינו כ”א בחירי ואיננו חזק כ”כ כהטבעי. ע”כ יש לחוש על קיומו, גם המדות הקדושות שהאומה הישראלית מעוטרות בהן חסרות הנה בהכרח, והמזג פועל על הבנים.

Finally, let me say something about RCA’s agreement with the Chief Rabbinate that all conversions already recognized by the RCA will be accepted in Israel. Unfortunately, I don’t believe that the Chief Rabbinate can deliver on this. That is because, as we have seen in the latest controversy, the dayanim are not bound by the Chief Rabbinate’s agreements. The Chief Rabbinate can accept a convert for its own purposes, but local dayanim have the autonomy to issue their own rulings, as we saw Rabbi Sherman do.

Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the agreement with the Chief Rabbinate will be upheld for a more fundamental reason: It violates the conscience and halakhic standards of the haredi world, which is currently taking over the religious court system. Let me explain what I mean. Many people who converted through RCA rabbis did not become completely observant. Some didn’t become observant at all. (I have already mentioned that this was the case with haredi rabbis as well.) If a dayan feels that such a conversion is invalid halakhically, the fact that the Chief Rabbinate made an agreement that all RCA conversions from previous years will be accepted is irrelevant. An agreement of this nature cannot override halakhah. So the dayan in question will be forced to reject this conversion no matter when it took place.

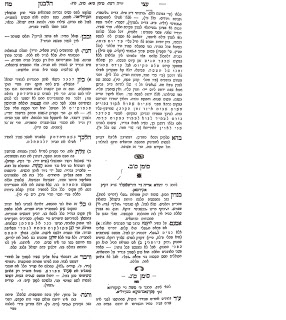

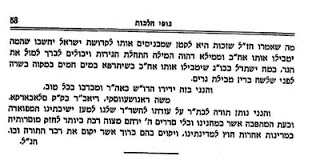

To show how difficult the situation can become, take a look at this article from

Yated Neeman that appeared a few years ago.

[43] I think we can get a good sense from it where we are heading with regard to conversion, and why the only solution is to have two separate court systems dealing with this matter. Yes, it is true that people converted by the Religious Zionist courts might not be accepted by the haredim, but so what? In the unlikely event that one of these converts or their children will want to marry a haredi, they can undergo a second haredi conversion. This is hardly a big deal, and certainly not reason enough for the Religious Zionists to entirely abandon their vision of halakhah, all in order to satisfy the haredi demands for a “single standard,” which by definition always means the haredi approach.

Contrary to Genack, the Modern Orthodox world would unquestionably still be eating non-glatt if it was available under (what they viewed as) reliable hashgachah. I also think everyone understood that my comments about the D symbol was not in criticism of identifying a product as dairy, but that the OU does not use the DE symbol (Incidentally, neither of these symbols existed when I was growing up. You knew if a product was dairy by looking at the ingredients, and one does not need to be concerned with the equipment unless you are specifically told – as you now are – that a product was made on dairy equipment. Even then, there are poskim who hold that you can ignore the DE and eat the product with meat, since despite what it says on the label, we don’t actually know that the parve food we are eating was produced within 24 hours of a dairy run.) Why do I think the D symbol instead of DE reflects a turn to the right?: I called the OU on three separate occasions and spoke to three different rabbis, and all of them explained that the reason DE is not used is because they have a fear that some small bits of milk might still be in the product. This is an incredible chumra, which incidentally has no real basis, as companies have to be very careful about not allowing milk into products which are non-dairy. (The threat of major lawsuits from people who are allergic to milk is a constant concern for the companies.) Furthermore, to claim that any such milk might exist in large enough quantities not to be batel is incredibly far-fetched. Despite raising these points in all three conversations, I was told that the organization chooses to be strict.

מעשה היה בעירי שטבח אחד הסגיר את הרב המשגיח בתיבת המקרה לערך חצי שעה ולא נתן לו לצאת, ואמרתי אז בדרוש על הטבח הזה שלכל הפחות היה לו פעם אחת בתיבת המקרה (שנקרא איז באקס) שלו חתיכה של בשר כשר.

For those who don’t read Hebrew: When the Mashgiach was locked in the freezer, Silverstone quipped that at least on one occasion there was a piece of kosher meat found there! See Yosef Goldman, Hebrew Printing in America 1735-1926 (Brooklyn, 2006), p. 765.

לפני כעשרים וחמש שנים, לאחר שנפטר הר”ר שמואל בלקין, והיו צריכים לבחור נשיא חדש לישיבה אוניברסיטה, החליט רבנו שאחד מהמועמדים לא היה ראוי לאותה אצלטא בגלל דיעותיו הבלתי-מסורתיות. רבנו כינס את כל הרמי”ם ביחד, וערך וניסח מכתב לועד-הנאמנים של הישיבה שהוא מתנגד מאוד להתמנותו של פלוני, וחתם את שמו למטה, ומסר את המכתב לשאר הרמי”ם שאף הם יחתמו. אחד מהרמי”ם פתח ושאל לרבנו, ומה כל הרעש הזה, מה פשעו ומה חטאתו של אותו פלוני. ענה רבנו ואמר, שיהודי המדפיס במאמר בעתון שלפי דעתו שני חלקי ספר ישעיה נכתבו על ידי שני בני אדם נפרדים, אפיקורס הוא, ואי אפשר למנותו כנשיא של הישיבה. והמשיך הלה לטעון ואמר, דהלא אף באברבנאל גם כן מצינו לפעמים דברים זרים אשר הם נגד מסורות רז”ל חכמי התלמוד. וענה רבנו ואמר, שאף את האברבנאל לא היה רוצה לראות כנשיא ישיבה-אוניברסיטה. ובזה נסתיים הויכוח. כל הרמי”ם שהיו נוכחים בשעת מעשה חתמו על מכתבו של רבנו, המכתב נמסר לועד הנאמנים, ונתבטלה מועמדותו של הלה.

I have it on very good authority (from conversations with two people who were intimately involved in the election process) that the event described here never happened. There might, however, be a kernel of truth in the story, as is often the case with such tales, and perhaps one of the readers can illuminate the matter. As for Rackman and Deutero-Isaiah, since he is not a Bible scholar I am certain that he never expressed his opinion in the way described here (I also hope that the Rav never said what is attributed to him. R Joseph Karo, Kesef Mishneh, Berakhot 3:8 refers to Abarbanel as הנשר הגדול)

The Talmud itself was not dogmatic, but contemporary Orthodoxy always feels impelled to embrace eveery Tradition as dogma. The Talmud suggests that perhaps David did not write all the Psalms. Is one a heretic because one suggests that perhaps other books were authored by more than one person or that several books attributed by the Tradition to one author were in fact written by several at different times? A volume recently published makes an excellent argument for the position that there was but one Isaiah, but must one be shocked when it is opined that there may have been two or three prophets bearing the same name? No Sage of the past ever included in the articles of faith a dogma about the authorship of the books of the Bible other than the Pentateuch. . . . How material is it that one really believes that Solomon wrote all three Scrolls attributed to him? Is the value of the writings itself affected? And if the only purpose is to discourage critical Biblical scholarship, then, alas, Orthodoxy is declaring bankruptcy: it is saying that only the ignorant can be pious – a reversal of the Talmudic dictum.

לפני כעשרים וחמש שנים, לאחר שנפטר הר”ר שמואל בלקין, והיו צריכים לבחור נשיא חדש לישיבה אוניברסיטה, החליט רבנו שאחד מהמועמדים לא היה ראוי לאותה אצלטא בגלל דיעותיו הבלתי-מסורתיות. רבנו כינס את כל הרמי”ם ביחד, וערך וניסח מכתב לועד-הנאמנים של הישיבה שהוא מתנגד מאוד להתמנותו של פלוני, וחתם את שמו למטה, ומסר את המכתב לשאר הרמי”ם שאף הם יחתמו. אחד מהרמי”ם פתח ושאל לרבנו, ומה כל הרעש הזה, מה פשעו ומה חטאתו של אותו פלוני. ענה רבנו ואמר, שיהודי המדפיס במאמר בעתון שלפי דעתו שני חלקי ספר ישעיה נכתבו על ידי שני בני אדם נפרדים, אפיקורס הוא, ואי אפשר למנותו כנשיא של הישיבה. והמשיך הלה לטעון ואמר, דהלא אף באברבנאל גם כן מצינו לפעמים דברים זרים אשר הם נגד מסורות רז”ל חכמי התלמוד. וענה רבנו ואמר, שאף את האברבנאל לא היה רוצה לראות כנשיא ישיבה-אוניברסיטה. ובזה נסתיים הויכוח. כל הרמי”ם שהיו נוכחים בשעת מעשה חתמו על מכתבו של רבנו, המכתב נמסר לועד הנאמנים, ונתבטלה מועמדותו של הלה.

I have it on very good authority (from conversations with two people who were intimately involved in the election process) that the event described here never happened. There might, however, be a kernel of truth in the story, as is often the case with such tales, and perhaps one of the readers can illuminate the matter. As for Rackman and Deutero-Isaiah, since he is not a Bible scholar I am certain that he never expressed his opinion in the way described here (I also hope that the Rav never said what is attributed to him. R Joseph Karo, Kesef Mishneh, Berakhot 3:8 refers to Abarbanel as הנשר הגדול)

The Talmud itself was not dogmatic, but contemporary Orthodoxy always feels impelled to embrace eveery Tradition as dogma. The Talmud suggests that perhaps David did not write all the Psalms. Is one a heretic because one suggests that perhaps other books were authored by more than one person or that several books attributed by the Tradition to one author were in fact written by several at different times? A volume recently published makes an excellent argument for the position that there was but one Isaiah, but must one be shocked when it is opined that there may have been two or three prophets bearing the same name? No Sage of the past ever included in the articles of faith a dogma about the authorship of the books of the Bible other than the Pentateuch. . . . How material is it that one really believes that Solomon wrote all three Scrolls attributed to him? Is the value of the writings itself affected? And if the only purpose is to discourage critical Biblical scholarship, then, alas, Orthodoxy is declaring bankruptcy: it is saying that only the ignorant can be pious – a reversal of the Talmudic dictum.

אם היא סברה שסדורי החיים שבקבוץ לא איפשרו לה דהוי כעין אונס שעומד לבוא עליה לפי דעתה ואינו חסרון בקבלת המצוות אף על פי שלדינא אינו אונס שהרי לא נאנסה להשאיר בקבוץ.

ופרט בזמנינו זה בעו”ה שרבים נכשלים בעבירה זו שאין להחשיבה כמומר לתיאבון.

See also the famous responsum of R. Akiva Eger (Teshuvot, vol. 1, no. 96), who deals with otherwise otherwise religious Jews who shave with a razor. (While reading his words ask yourself if the community he describes sounds more like a haredi community or a Modern Orthodox one.):

י”ל דהשתחת בתער דנתפשט בעו”ה אצל הרבה לא חשב שזהו איסור כ”כ דלא משמע להו לאינשי דאסור, וכאשר באמת נזכר בג”ע שהשיב להמוכיח שהרבה אנשים חשובים עושים כן, וכיון דבאמת פשתה המספחת בזמנינו גם לאותן הנזהרים בשאר דברים נדמה להם דאינו איסור כ”כ.

R. Eliezer Papo, Pele Yoetz, s. v. hov, writes:

ע”פ מה דקיימא לן אומר מותר אנוס הוא ומאחר שדרך איש ישר בעיניו נמצא שהוא אומר מותר ואנוס הוא.

The last three sources mentioned are quoted by R. Zvi Yehudah Kook, Li-Netivot Yisrael, vol. 1 pp. 154-155.

לא ברור הדבר במדינה זו שהוא זכות כיון שבעוה”ר קרוב שח”ו לא ישמור שבת וכדומה עוד איסורים. אך אפשר שמ”מ הוא זכות שאף רשעי ישראל עדיפי מעכו”ם.

וגם אף אם לא יתגדלו להיות שומרי תורה מסתבר שהוא זכות דרשעי ישראל שיש להם קדושת ישראל ומצותן שעושין הוא מצוה והעבירות הוא להם כשגגה הוא ג”כ זכות מלהיות נכרים.

מה לנו להתחכם נגד מצות ד’ . . . מצינו כי אדם רע עשוי לעשות תשובה, וגם כאן נאמר כי עוד יבוא יום וישעה אדם אל עושהו ותפקחנה עיני עורים וידעו כי ערומים הם והרבה לחטוא.

ודאי דזרע אברהם יצחק ויעקב המיוחסים מתרחקים מן הגרים כפי האפשר הגם שמקרבים אותם מצד מצות ואהבתם את הגר אבל אין זה מצוה לנו להתחתן עמהם.

I certainly think he is going overboard when he writes (ibid., vol. 15, p. 151): ואין ממנים גר להיות שמש בביהכ”נ