Conservative Conversions, Some Grammatical Points, and a Newly Published Section of a Letter from R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik

Marc B. Shapiro

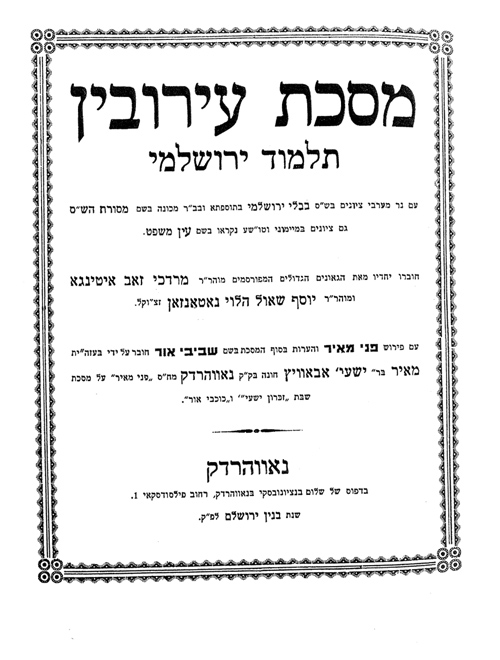

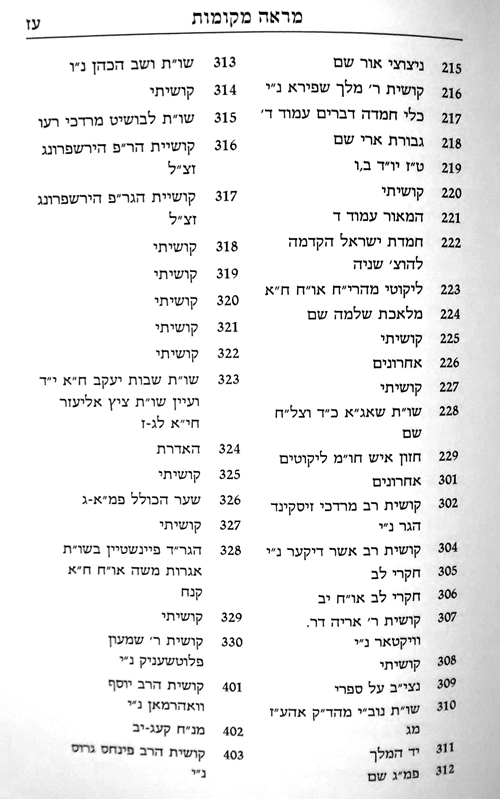

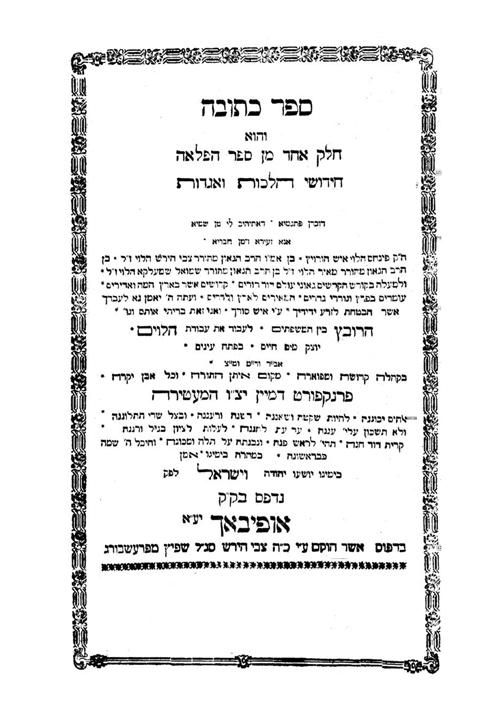

1. Since I mentioned R. Ovadiah Hoffman in the last post, I would be remiss in not noting that he and his brother, R. Yissachar Dov, recently published volume 4 of

Ha-Mashbir, devoted to R. Ovadiah Yosef. It can be purchased

here.

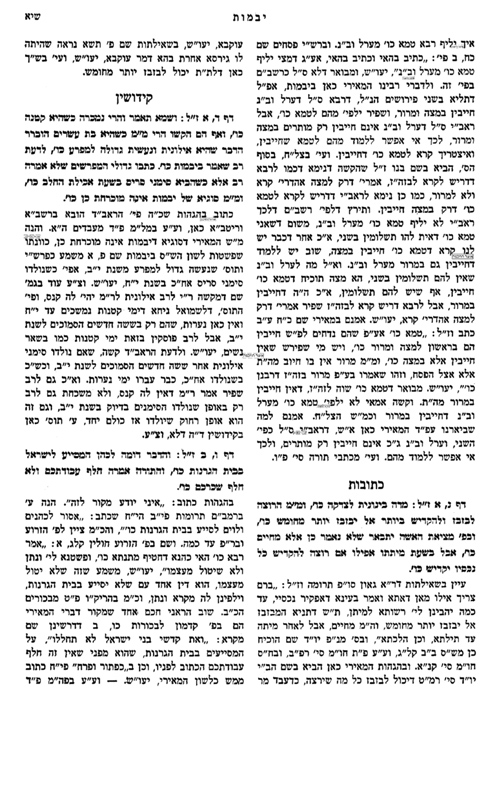

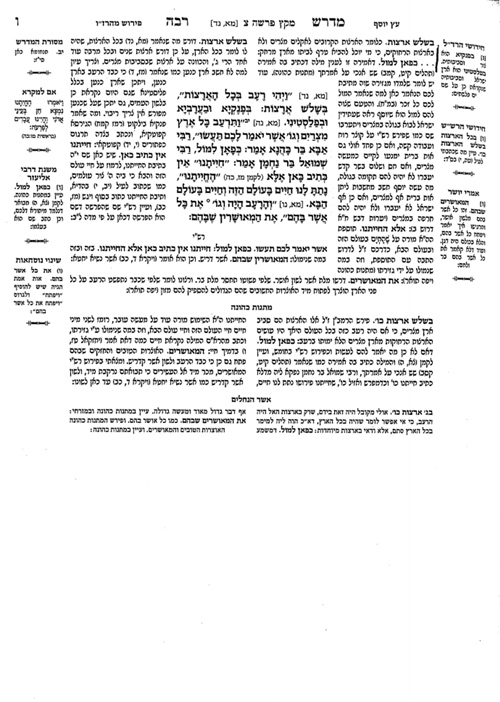

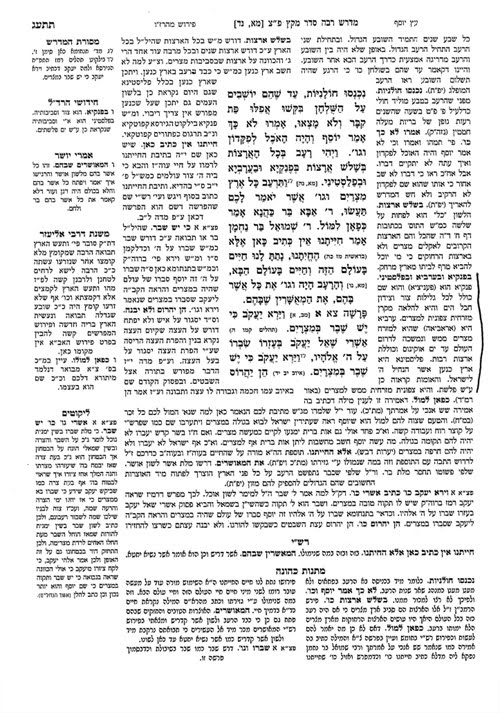

The volume contains a previously unpublished letter by R. Ovadiah Yosef that I provided, dealing with a rabbi who improperly converted people. It also contains a number of other noteworthy sections, such as R. Ovadiah’s notes to R. Ben Zion Uziel’s Mishpetei Uziel, talmudic notes from R. Uziel published from manuscript, R. Meir Mazuz’s notes to R. Ovadiah’s Yehaveh Da’at, and many valuable articles by contemporary Torah scholars, including the editors. Of particular interest to me was R. Yissachar Dov Hoffman’s article on the practice of a number of great Torah sages of prior generations not to kiss their children. Such a practice is so much against the contemporary mindset of what is regarded as healthy that, as R. Hoffman notes, even a Satmar rabbi, R. Israel David Harfenes, has stated that “in our time it is forbidden to follow this path” (p. 293).

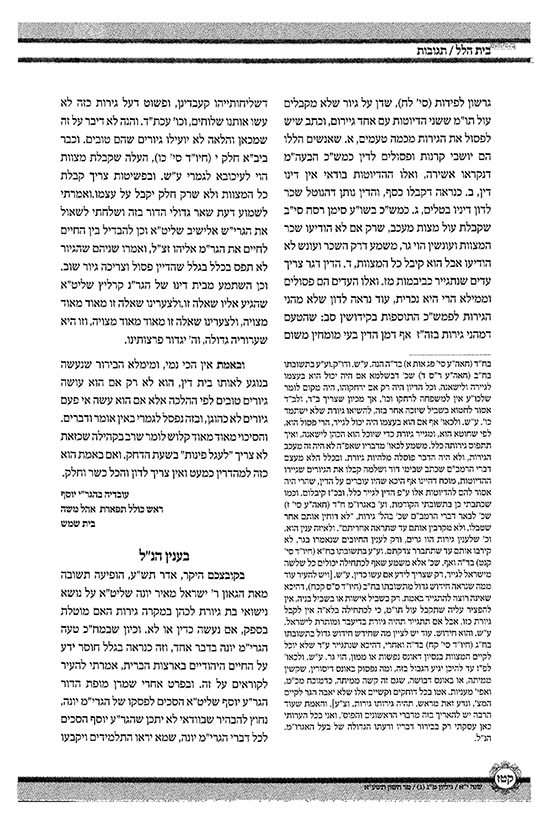

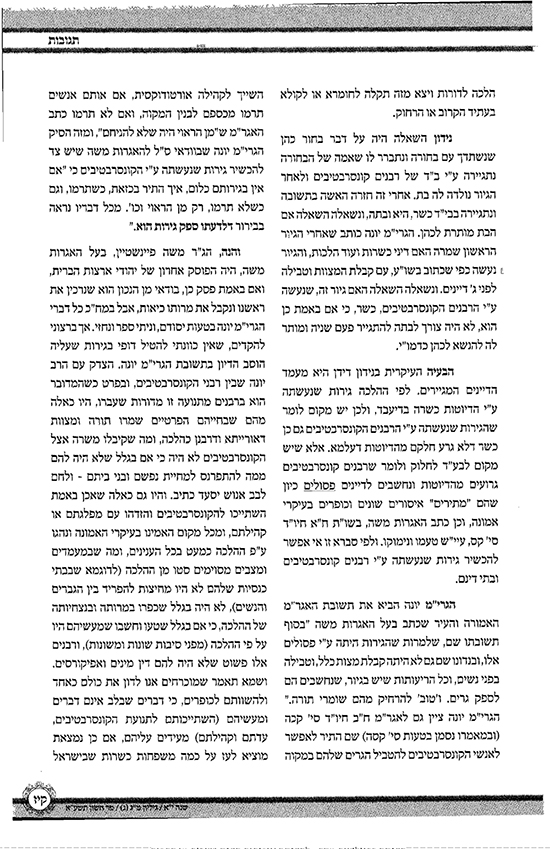

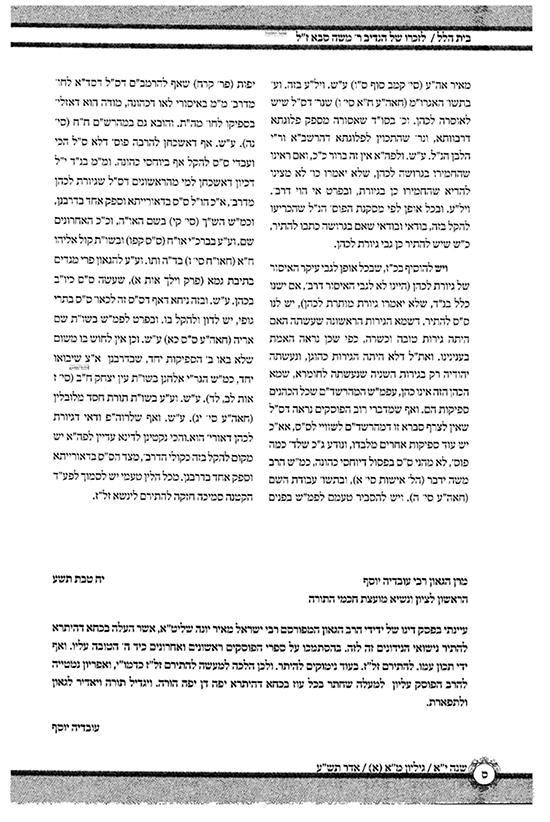

Apropos of the above-mentioned responsum on conversion by R. Ovadiah Yosef, in

Beit Hillel, Adar 5770, R. Yisrael Meir Yonah deals with a conversion done by a Conservative beit din. He rules that in this particular case the conversion is valid. This ruling was affirmed by R. Ovadiah.In his responsum, R. Yonah states that R. Moses Feinstein regarded Conservative conversions as doubtful conversions rather than completely invalid, and brought two supposed proofs for this. I responded to R. Yonah in

Beit Hillel 43 (Heshvan 5770), and you can see my letter here.[1]

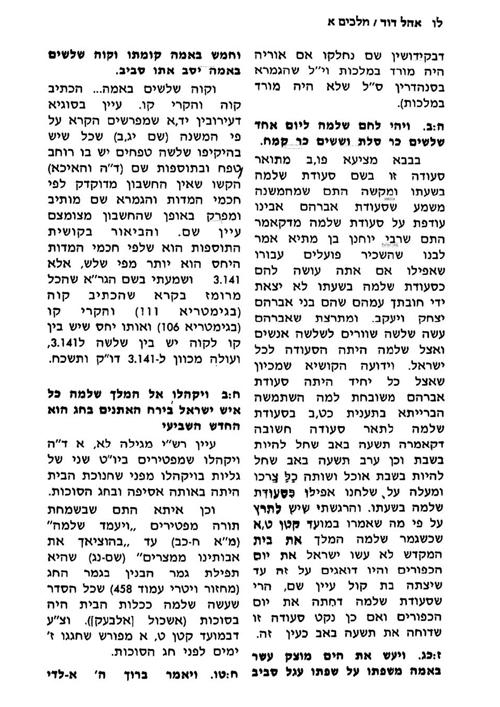

To his credit, R. Yonah acknowledged that he was mistaken in his reading of R. Feinstein’s responsum.[2] It is also the case, as I mention in my letter, that it is possible that a conversion done by a Conservative rabbi, especially from years ago, could be halakhically valid. R. Feinstein himself, who wrote very strongly against Conservative conversions, also writes about such a conversion: כמעט ברור שאין עושין הגרות כדין. The word כמעט shows us that even R. Moshe recognized that there are times when a Conservative conversion can be halakhically valid. In Mesorat Moshe, vol. 1, p. 327, we see as well that R. Moshe acknowledged the possibility that a Conservative conversion could be valid:

אולי יש להסתפק דאפשר לא היו ב”ד של פסולים, דיש אנשים, בעצם דתיים ומאמינים, שמחמת דוחק פרנסה מקבלים משרה כרבנים אצלם, ואפילו אם למדו בסמינר שלהם, אולי בעצמו כן מאמין. ולפיכך למעשה, אם זה אפשר לברר, תבררו. ואם קשה לברר, אז אולי שייך להגיד השערה, שאם זה בכפר או עיר רחוק מעיקר ישוב היהדות הדתי מסתמא אין להסתפק, בוודאי אינו כלום. ואם זה בעיר שיש בו ישוב דתי, נו, אזי כן יש ספק.

I also know someone who offers eyewitness testimony that R. Moshe did not think that every Conservative conversion could be voided without investigation, especially as this would mean that women married to these converts would then be able to remarry without a get. R. Moshe was not willing to go this far.

Similarly, R. Ovadiah Yosef, when asked about a Conservative conversion, replied that before giving a ruling it was necessary to find out which Conservative rabbi did the conversion, “since the Conservatives are not all alike.”[3]

R. Ovadiah was also asked about a woman who had become religious and was interested in going out with a kohen for the purpose of marriage. The problem was that she had slept with a man whose mother was converted by a Conservative rabbi. This man’s family was somewhat traditional as they kept kosher, made kiddush, and lit Shabbat candles. Could the woman in question marry a kohen, which is forbidden if she had slept with a non-Jew? The answer to this question depends on the status of the man whose mother was converted by a Conservative rabbi. If the conversion was invalid then the man was also to be regarded as a non-Jew, and the woman we are discussing, who slept with this man, would be forbidden to a kohen.

R. Ovadiah replied that the woman could marry a kohen, which means that be-diavad he accepted the Conservative conversion. He gave this ruling without even seeking further knowledge about the particular rabbi who did the conversion under question, which appears to me to be an incredible leniency. In seeking to explain this ruling, R. Yehudah Naki writes, “We see that they observed some mitzvot, so be-diavad there is more room to be lenient, at least not to forbid others” (that is, to forbid the woman from marrying the kohen).[4]

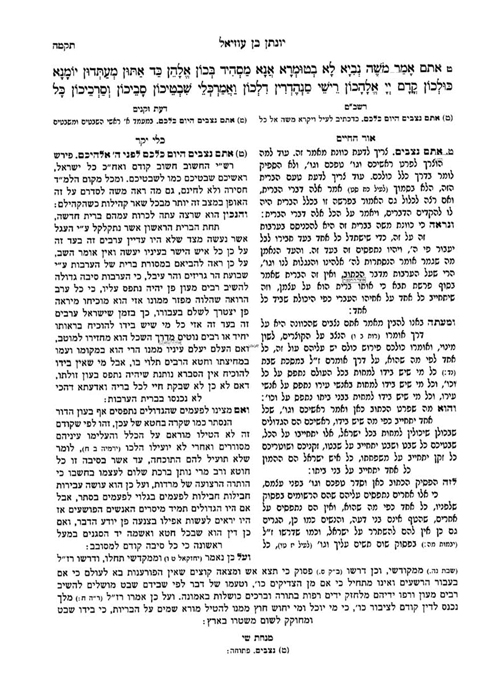

As mentioned, R. Ovadiah accepted R. Yonah’s pesak that a particular conversion carried out by a Conservative beit din was valid. In this case, the daughter of a woman who had been converted wished to marry a kohen. This would only be allowed if the daughter was born Jewish, meaning that everything depended on the status of her mother’s conversion. Here is how R. Yonah described this particular Conservative beit din.[5]

ובירורים שעשינו בנ”ד התברר לנו שב”ד הזה שגיירוה, הם אנשים שנקראים וידועים כשומרי תורה ומצוות, ובעצם הם אורטודוכסים, וגם הגיור שעשו, ע”פ כל החקירות ודרישות שעשיתי, הקפידו בכל הדברים כולם, הן בטבילה, חציצה וכו’ וכו’, הן בקבלת מצות, ולימודי יהדות קודם הגיור, לא פחות ואולי יותר, מהרבה בתי דינים אחרים שנחשבים לחרדיים. וא”כ אין כל סיבה לפע”ד לפסול גיור זה.

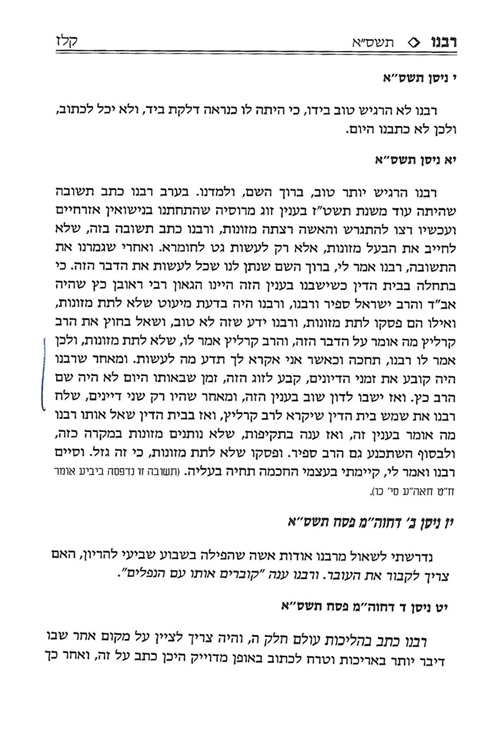

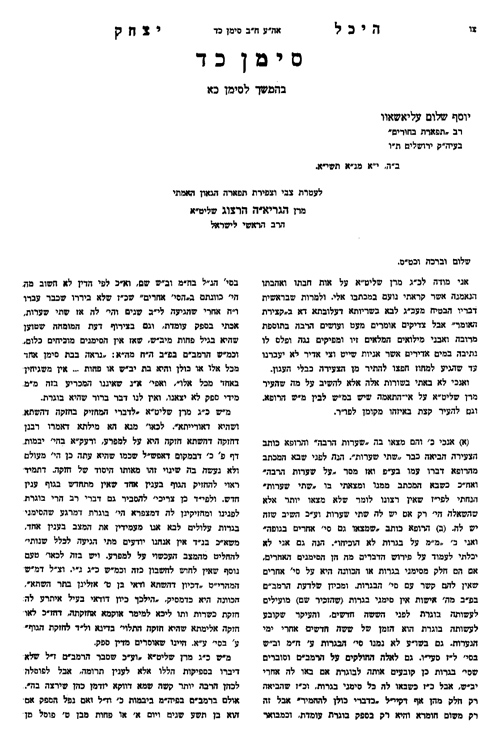

Here is R. Ovadiah’s affirmation of R. Yonah’s

pesak, from

Beit Hillel, Adar 5770, p. 60.

That a Conservative conversion might be valid also appears to be assumed by R. Mordechai Eliyahu. This is what he writes in his Ma’amar Mordechai, vol. 2, Even ha-Ezer, no. 16:

ובענין הגר שנתגייר אצל הקונסרבטיבים והוא אינו שומר תורה ומצוות, והיה לכם ספק אם אפשר לכתוב שם יהודי שניתן לו, שם שלא השתמש בו מעולם, או לכתוב בן אאע”ה. נראה לי, מאחר וכל עצם נתינת הגט של אדם זה הוא לחומרא ולא מדינא, כי מי אמר שגרותו – גרות, וגיוריהם של הרבנים הקונסרבטיבים – גיור . . .

R. Eliyahu does not say that there is absolutely no reason for a get when dealing with a Conservative conversion. Rather, he refers to it as a humra. Also, note how he states, “who says that his conversion was a [valid] conversion?” This is the language of safek. He does not say, “certainly his conversion was invalid.”[6]

2. In a previous post

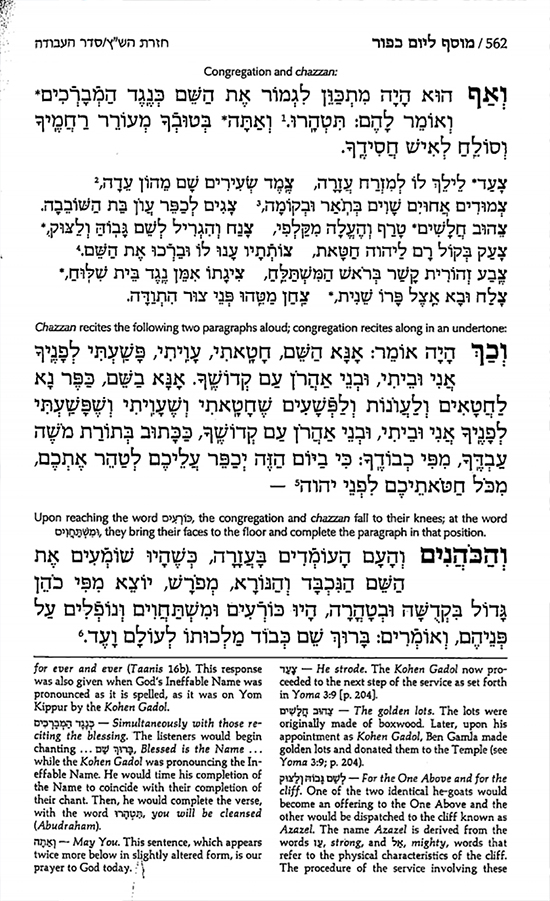

here I mentioned a few common pronunciation mistakes in Kiddush. There is one more that I would like to mention, but it is a little more complicated than the ones I previous noted. In the Friday night kiddush we say כי הוא יום תחלה למקראי קודש. Where is one supposed to put the accent in the word למקראי? If you look at ArtScroll you find that it puts the accent on the penultimate syllable, the ר. However, Koren and most of the other siddurim I checked put the accent on the final syllable, the א.

I don’t know why this should be a matter of dispute, because the Torah itself uses the expression מקראי קודש three times (Lev. 23:2, 4, 37), and in every case the accent in מקראי is on the final syllable.[7] The Yom Tov morning kiddush also begins: אלה מועדי ה’ מקראי קודש. For some reason ArtScroll is not consistent, and in this case it puts the accent in מקראי on the א.

After my last post someone emailed me pointing out that another “common mistake” is that in Birkat ha-Mazon, in the second paragraph, people say נודה לך putting the accent on the first syllable instead of the second. In fact, the tune for Birkat ha-Mazon that American children are taught at schools around the country has the word נודה recited with the accent on the first syllable. Should we now start teaching all the children differently, so that they pronounce נודה with the accent on the second syllable which is how ArtScroll, Koren, and almost all the other siddurim have it?

Actually, this matter is not clear at all. I say this because if you open up a Tanakh to Psalms 79:13 and look at the words נודה לך you will find different versions. Some have the word נודה with the accent on the final syllable and others have the accent on the first syllable. The Aleppo Codex has the accent on the first syllable and puts a dagesh in the ל of לך. Although the practice of American children (and adults) pronouncing the word נודה with the accent on the first syllable has nothing to do with the Aleppo Codex, the fact that this pronunciation appears in such an important source means that there is no reason to change how the children are taught. However, this creates a problem because in the Amidah, in Modim, we say נודה לך ונספר תהלתך. If we are going to recite נודה of Birkat ha-Mazon with the accent on the first syllable, then we should be consistent and do the same thing in the Amidah, in ברוך ה’ לעולם in ma’ariv: נודה לך לעולם, and also in the so-called “Three-Faceted Blessing” (ברכה מעין שלש – Al ha-Mihyah): ונודה לך על הארץ.

Speaking of consistency, in Birkat ha-Mazon, the Amidah, ברוך ה’ לעולם, and the Three-Faceted Blessing, both the regular ArtScroll siddur and Koren have the accent in נודה on the final syllable. However, in the Amidah, ברוך ה’ לעולם, and the Three-Faceted-Blessing they both place a dagesh in the ל of ונודה לך and נודה לך, but do not place a dagesh in the ל of נודה לך in Birkat ha-Mazon. This makes no sense. If there is a dagesh in one there must be a dagesh in all of them. (In the Hebrew-only ArtScroll siddur they also put a dagesh in the in the ל of נודה לך in Birkat ha-Mazon.)

I think it is a mistake for ArtScroll and Koren to place a dagesh in לך in any of these instances. Since no exception with נודה לך is found in Tanakh, the only reason there would be a dagesh in לך is if the word נודה has the accent on the first syllable, as in the Aleppo Codex (and unlike what appears in ArtScroll and Koren), or if there is a makef between the two words.[8]

Regarding the word נודה, it is worth noting that in Ein Ke-loheinu there is no question that נודה is to be read with the accent on the final syllable (as the matter of where to put the accent in נודה only concerns the phrase נודה לך). Here is an example where the common tune, which puts the accent on the first syllable, cannot be defended grammatically.

I noticed two mistakes in the regular ArtScroll siddur which appear correctly in Koren. In the morning blessings we say אשר נתן לשכוי בינה. Where is the accent in the word לשכוי? ArtScroll puts the accent on the final syllable, and Koren puts the accent on the penultimate syllable, on the ש. Koren is correct as there is an explicit verse in Job 38:36: מי נתן לשכוי בינה. If you look at the trop on this verse you will find that the accent in לשכוי is on the penultimate syllable. Interestingly, in the Hebrew-only ArtScroll siddur they get this right.

The other mistake is that in Birkat ha-Mazon on Sukkot we say:

הרחמן הוא יקים לנו את סכת דויד הנופלת

ArtScroll puts a kamatz under the פ in הנופלת. Koren puts a segol and that is correct. We see this from the appearance of the word in Amos 9:11, and there is no change of vowel even on the etnahta.[9]

I also found an example where ArtScroll gets it right and Koren is mistaken. In ma’ariv, in the paragraph ואמונה כל זאת, we say העושה לנו נסים. Koren has העושה with the accent on the final syllable and the ל of לנו with a dagesh. Yet this doesn’t work. For there to be a dagesh in the ל, the prior word, העושה, has to have the accent on the penultimate syllable, which is how it appears in ArtScroll.

Another example where ArtScroll gets it right and Koren gets it wrong is in the morning blessings where we say שעשה לי כל צרכי. Koren puts the accent in שעשה on the final syllable. Yet this is a mistake, and as is correctly found in ArtScroll the accent is on the penultimate syllable, the ע.

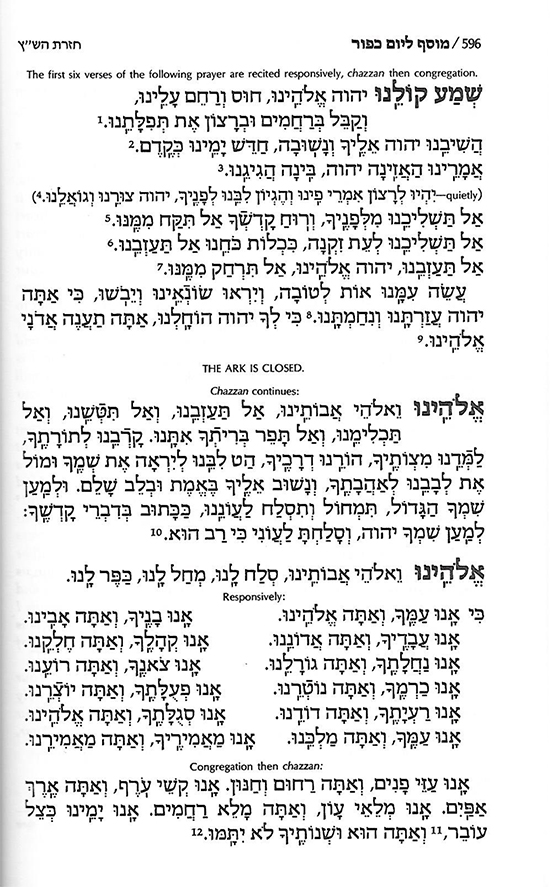

Since I have been speaking about the ArtScroll siddur, let me add a couple of comments about the Yom Kippur Machzor. Here is how

Shema Kolenu appears in my copy of the Yom Kippur Machzor (p. 596).

The instructions tell us that “the first six verses of the following prayer are recited responsively, chazzan then congregation.” The problem is that I have never seen a synagogue that says the verses beginning אמרינו and אל תעזבנו responsively. What all these synagogues do is say the following four verses responsively:

שמע קולנו

השיבנו

אל תשליכנו מלפניך

אל תשליכנו לעת זקנה

In my experience, not only does no one say the verses beginning אמרינו and אל תעזבנו responsively, but they don’t say יהיו לרצון quietly either.

The text recorded by ArtScroll is the one found in many old Ashkenazic machzorim. So when and how were אמרינו and אל תעזבנו dropped from the responsive reading, or is it that from the beginning they were not included? As for יהיו לרצון, the old machzorim do not indicate that this is said quietly, so was there ever a tradition to recite it quietly or is ArtScroll simply trying to make sense of a verse that is found in the Machzor but no longer appears to be recited? If יהיו לרצון was originally part of the public reading, we again have to ask, why was it dropped?

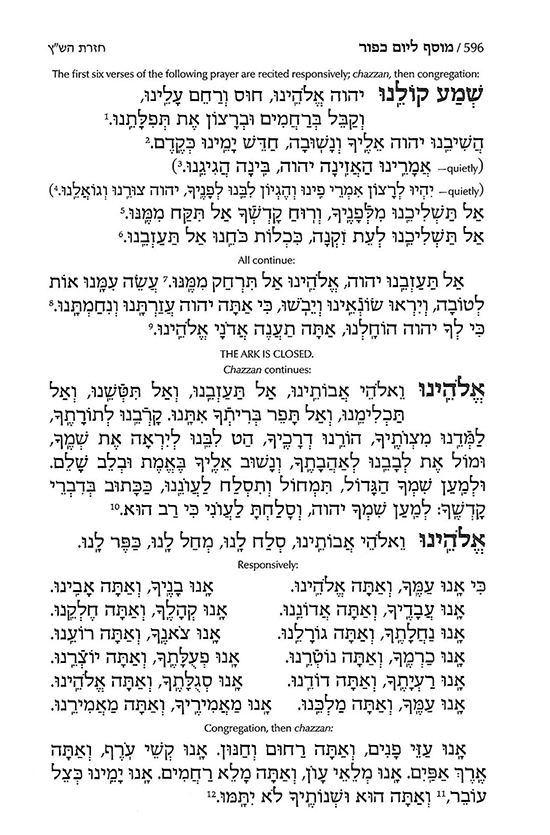

Recognizing the problem, in the new edition of the ArtScroll machzor they made a change.

As you can see, אל תעזבנו has now been pushed to the next paragraph. We are also instructed that both אמרינו and יהיו לרצון are to be said quietly. Yet this doesn’t seem to make any sense, as those who are reciting Shema Kolenu responsively will not be saying these verses quietly. And again, I ask, is there any real tradition that these verses are to be said quietly, or is this something made up by people in an attempt to keep the traditional text of the Machzor while dealing with the fact that these verses are not part of the responsive reading? Unfortunately, when updating the Machzor, ArtScroll did not correct the instructions which still refer to the “first six verses” as being recited responsively, when instead it should say the “following four verses”.

Here is how Koren has the prayer.

This version, which puts אמרינו and יהיו לרצון before the final verse, is also attested to in prior machzorim, though the order found in ArtScroll appears to be the older version.To sum up, I am not sure what the best path for ArtScroll would have been. On the one hand, they could have adopted the version found in Koren, which solves all the problems. Keeping what appears to be the more authentic version, which they did, also makes sense, but then they were forced to add the instructions that certain verses are to be said silently. I have checked numerous old machzorim and there is no indication that these verses are to be said silently. Was there perhaps an oral tradition in this matter? Perhaps readers can comment on this. In any event, ArtScroll’s instructions are problematic, since, as mentioned, if people are reciting the prayer responsively, they are not going to be inserting two consecutive sentences quietly.

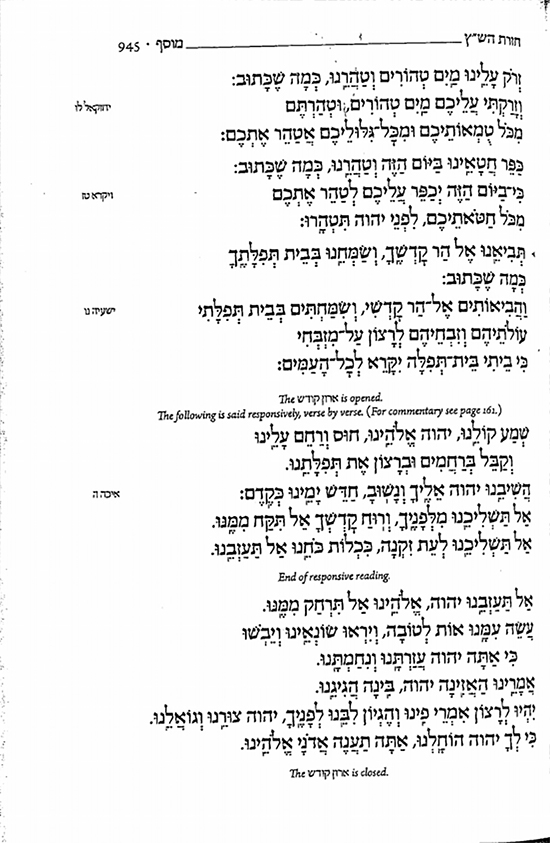

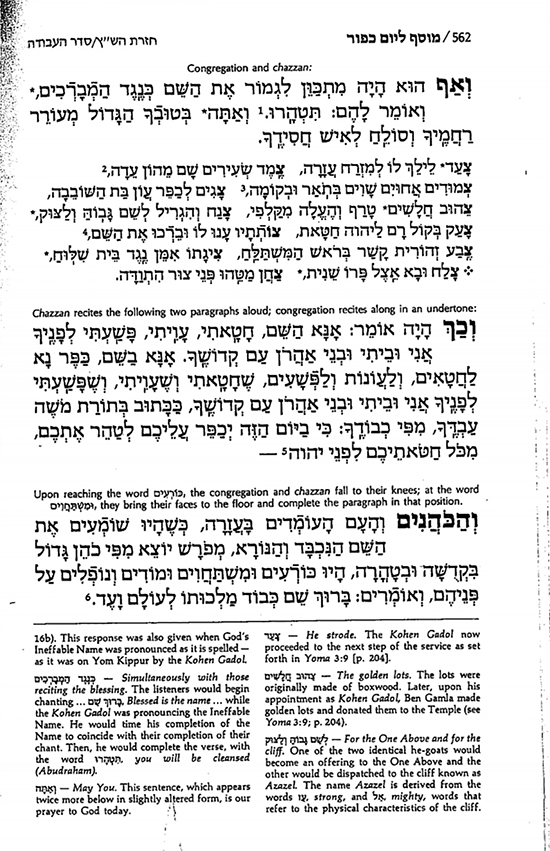

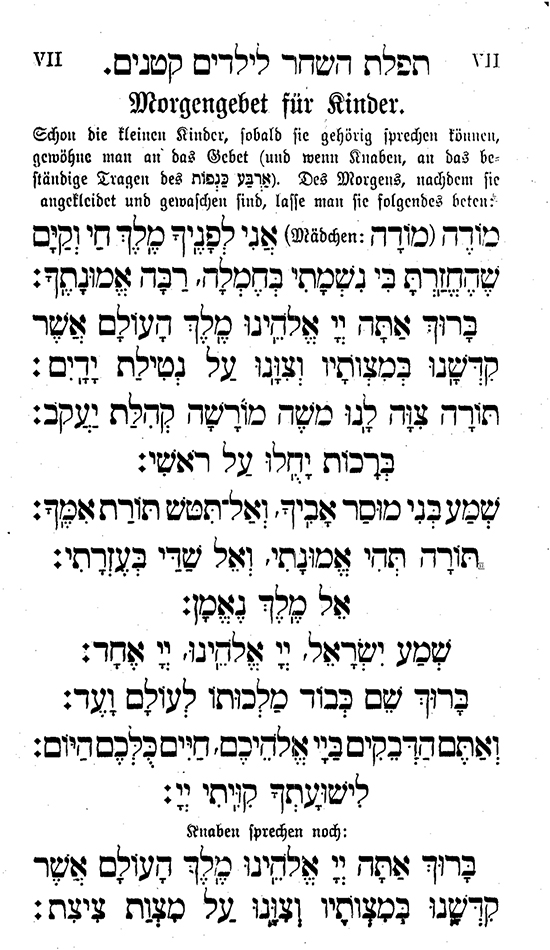

I noticed another interesting change in the ArtScroll Yom Kippur machzor between the old edition and the new one. Here is והכהנים והעם in the old edition.

It reads היו כורעים ומשתחוים ומודים ונופלים על פניהם.

Here is the new edition, where the word ומודים has been deleted. ArtScroll neglected to change the English translation, so it still appears, now incorrectly, as: “they would kneel and prostrate themselves, give thanks, fall upon their faces.”

Why was the word ומודים deleted? Based on what I have been able to determine, the version without the word ומודים is more common, so presumably that is the reason. Although most people might just chalk this up to a different girsa, R. Soloveitchik saw great significance in the alternative versions, and explained their different implications.[10]

Here are a couple of random mistakes I found in ArtScroll. (I use the ArtScroll siddur every day of the week, which is how I have come across these. I am sure that if I used Koren, I would find mistakes there too.) In the ArtScroll siddur, p. 86 it reads:

ואל מאורי אור שעשית, יפארוך, סלה

There is a dagesh in the ס of סלה. This means that the comma after יפארוך is a mistake, as you cannot place a dagesh in this ס if preceded by a comma.

Another mistake is found on p. 702, in the prayer for dew, which states בעם זו בזו. Its translation is correct: “Among this people, through this prayer.” However, I would have preferred if it appeared as follows: “Among this people, through this [prayer],” which would be a more accurate rendition of the few words. (This is indeed how it is translated in the ArtScroll Passover Machzor.)ArtScroll vocalizes these words be-am zu be-zu. Yet this is incorrect. בזו should be pronounced be-zo, referring to תפלה, the feminine Hebrew word for prayer. Koren gets this correct. This confusion of ArtScroll with zu and zo is also found on p. 202, where in the marriage service we find בטבעת זו and ArtScroll pronounces it zu, instead of zo. Again, Koren gets it right. (The word זו often appears in the Talmud, and the ArtScroll Talmud always pronounces it correctly.)

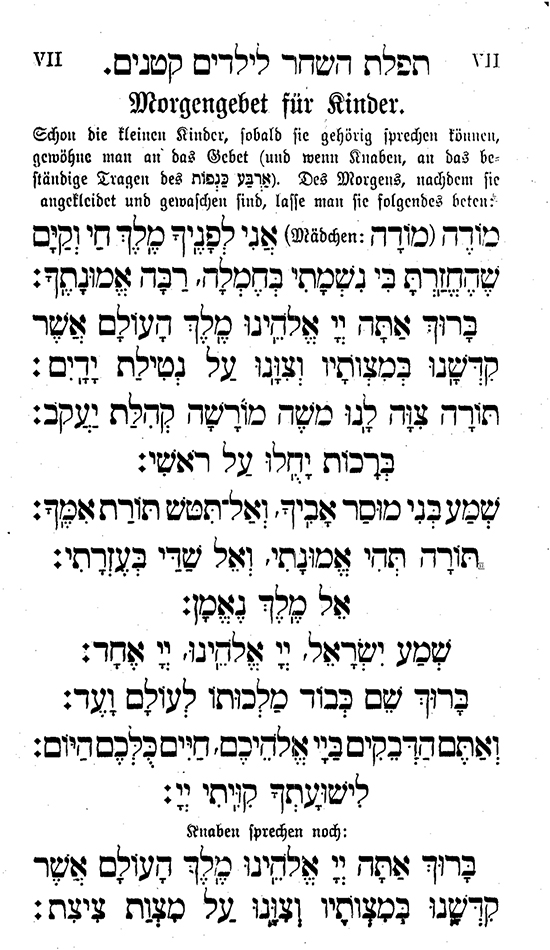

Let me close with one final mistake in ArtScroll, or perhaps it is not a mistake; readers can decide on their own. The ArtScroll Ohel Sarah Women’s Siddur is a special siddur designed for women. On the very first page of the prayers, this siddur has מודה אני with a segol under the ד. In a women’s siddur doesn’t there need to be a kamatz under the ד so that it reads modah?

This might reflect a broader issue. My experience is that in co-ed kindergartens the girls are also taught to say modeh. This might not be surprising, but I was also told by a number of people that even in girls-only kindergartens, both Ashkenazic and even some Sephardic ones, the girls are taught to say modeh. No doubt recognizing this problem, R. Yitzhak Yosef makes a point of placing a kamatz under the ד so that people will know how women are to pronounce the word.[11] R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach likewise told the women in his family to say modah.[12]It is noteworthy that in one of the editions of Wolf Heidenheim’s Siddur Sefat Emet, found on Otzar ha-Hokhmah, girls are instructed to say modah.

However, this edition appeared after Heidenheim’s death, and unfortunately there is no way to determine exactly when. (The Basel 1956 date on the title page is just the date of the photo-offset edition, not the original.) As far as I can tell, none of the siddurim that appeared in Heidenheim’s lifetime distinguish between men and women with regard to modeh-modah.In response to questioners, R. Hayyim Kanievsky also stated that women are to pronounce the word as modah.[13] Despite this, when R. Meir Arbah asked Rebbetzin Batsheva Kanievsky, R. Hayyim’s wife, what she did, she replied that she pronounced it modeh![14]

The ArtScroll Women’s siddur also has שלא עשני גוי and not גויה and שלא עשני עבד instead of שפחה. This too would seem to be incorrect in a women’s siddur, but the standard version is defended by R. Shmuel Wosner, as he claims that the words גוי and עבד include both men and women.[15] More about this in the next post.

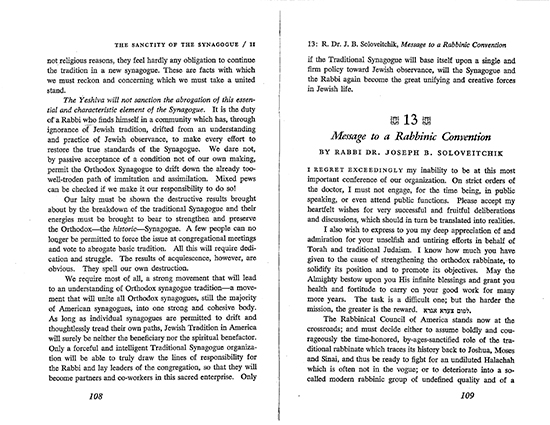

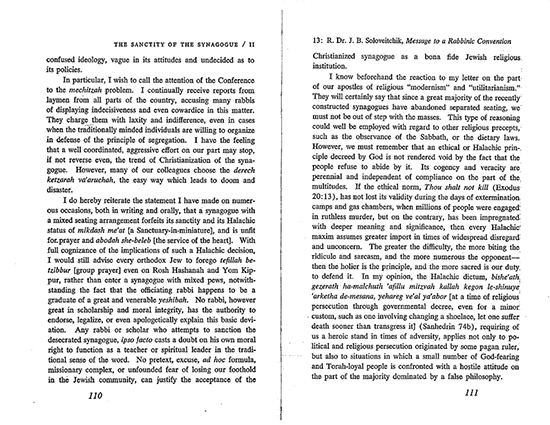

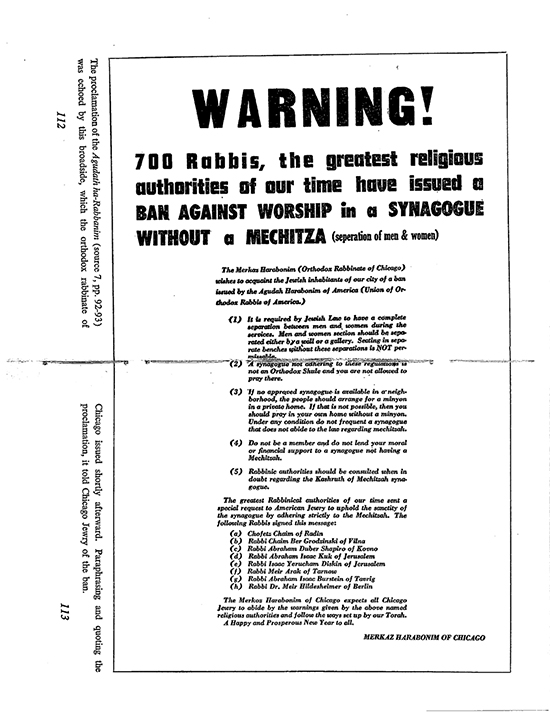

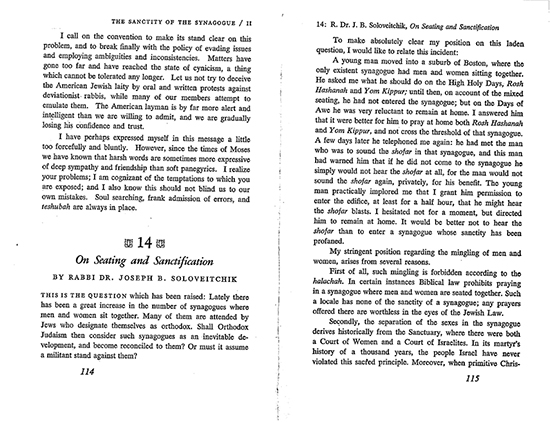

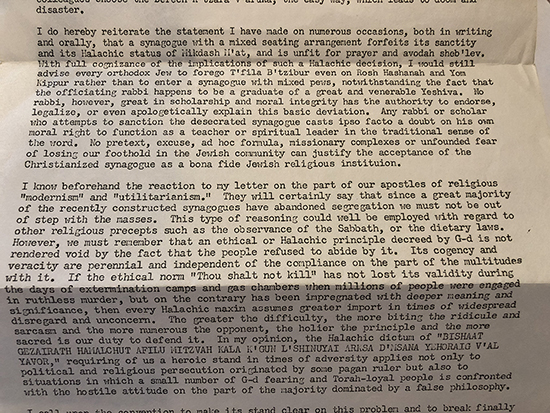

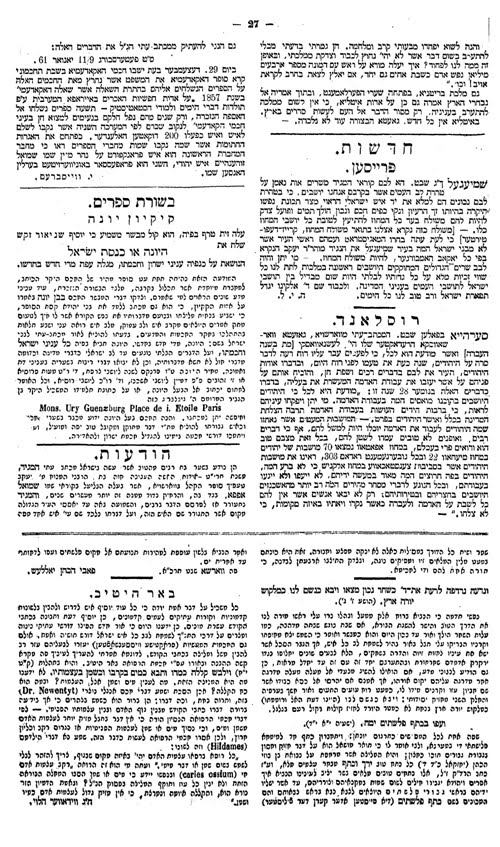

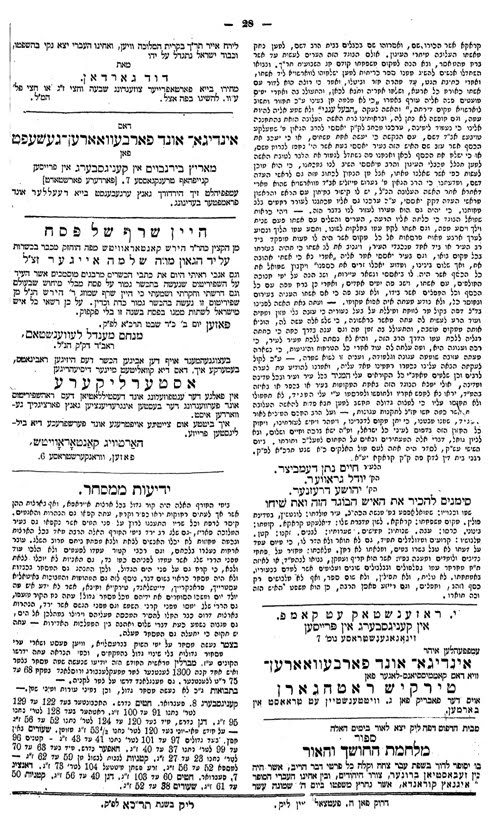

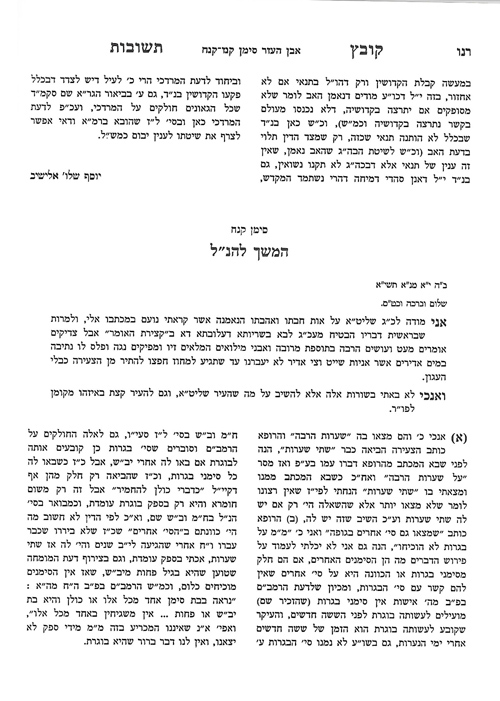

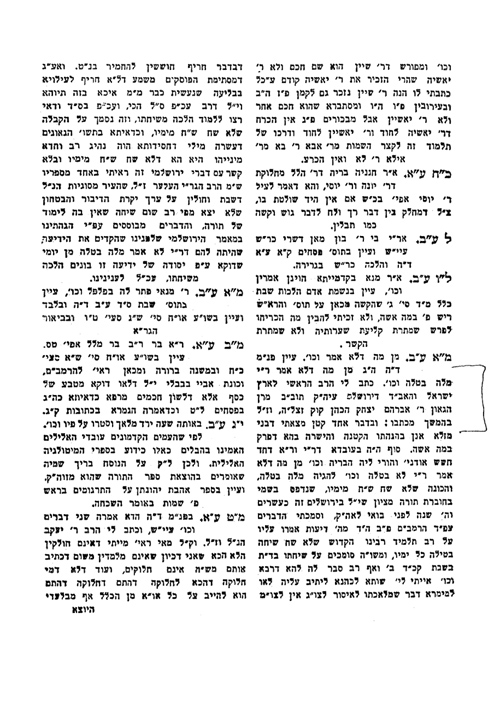

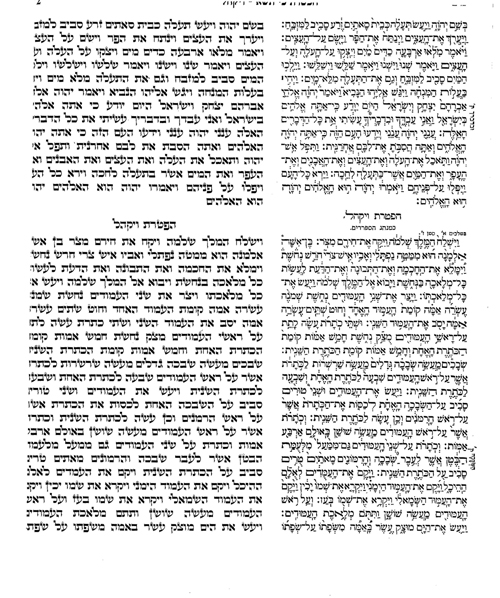

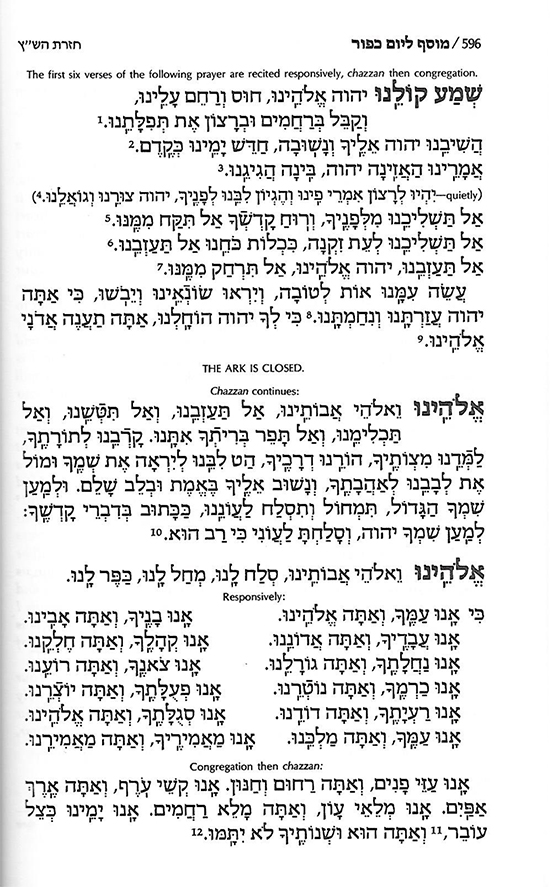

3. We all know that everything written by R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik is precious.[16] One area in which the Rav was very eloquent and forceful was with regard to the necessity of having a mehitzah in shul. In Baruch Litvin’s 1959 book,

The Sanctity of the Synagogue, pp. 109-114, it prints a letter from the Rav to an RCA convention.

This letter has been reprinted in Nathaniel Helfgot, Community, Covenant and Commitment, pp. 139-142.

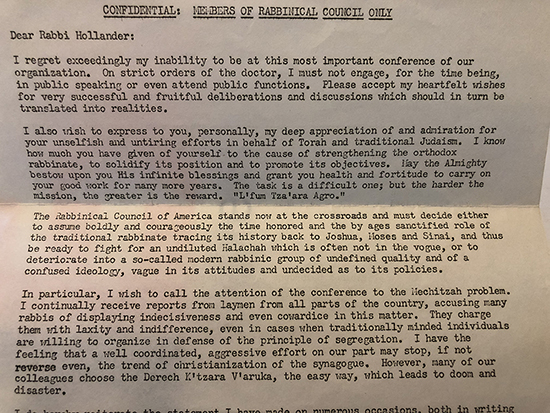

One interesting point which is not found in the Litvin book is that the Rav’s letter, while intended for RCA members, was addressed to R. David Hollander, the president of the RCA at the time. This is important to note because in the second paragraph he is speaking personally to R. Hollander and praising him for his good works. However, the reader of the letter in Litvin’s book will mistakenly think that the Rav is speaking to the RCA as a whole.

Furthermore, some of what R. Soloveitchik included was deleted from the letter as it appeared in the Litvin book. This was apparently because his points were not specifically relevant to the mehitzah issue. I am happy to be able to present here the omitted words of the Rav which until now have never been published, and which present an important personal statement about the halakhic process. Readers should note the end of the second paragraph that is transcribed below, as it is criticism of certain members of the RCA. Similar sentiments are found earlier in the letter (Litvin, p. 110, first paragraph), where the Rav concludes his paragraph with the strong words: “However, many of our colleagues choose the derech ketzarah va’aruchah, the easy way which leads to doom and destruction.”

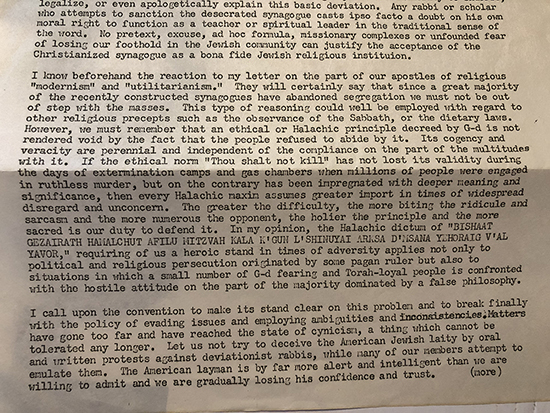

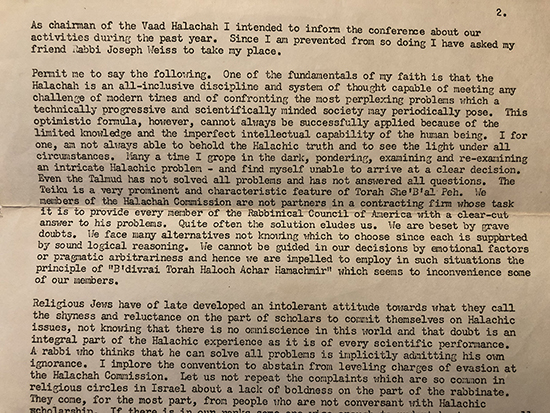

As chairman of the Vaad Halachah I intended to inform the conference about our activities during the past year. Since I am prevented from doing so I have asked my friend Rabbi Joseph Weiss to take my place.

Permit me to say the following. One of the fundamentals of my faith is that the Halachah is an all-inclusive discipline and system of thought capable of meeting any challenge of modern times and of confronting the most perplexing problems which a technically progressive and scientifically minded society may periodically pose. This optimistic formula, however, cannot always be successfully applied because of the limited knowledge and the imperfect intellectual capability of the human being. I for one, am not always able to behold the Halachic truth and to see the light under all circumstances. Many a time I grope in the dark, pondering, examining and re-examining an intricate Halachic problem – and find myself unable to arrive at a clear decision. Even the Talmud has not solved all problems and has not answered all questions. The Teiku is a very prominent and characteristic feature of Torah She-B’al Peh. We members of the Halachah Commission are not partners in a contracting firm whose task it is to provide every member of the Rabbinical Council of America with a clear-cut answer to his problems. Quite often the solution eludes us. We are beset by grave doubts. We face many alternatives not knowing which to choose since each is supported by sound logical reasoning. We cannot be guided in our decisions by emotional factors or pragmatic arbitrariness and hence we are impelled to employ in such situations the principle of “B’divrai Torah Haloch Achar Hamachmir” which seems to inconvenience some of our members.

Religious Jews have of late developed an intolerant attitude towards what they call the shyness and reluctance on the part of scholars to commit themselves on Halachic issues, not knowing that there is no omniscience in this world and that doubt is an integral part of the Halachic experience as it is of every scientific performance. A rabbi who thinks that he can solve all problems is implicitly admitting his own ignorance. I implore the convention to abstain from leveling charges of evasion at the Halachah Commission. Let us not repeat the complaints which are so common in religious circles in Israel about a lack of boldness on the part of the rabbinate. They come, for the most part, from people who are not conversant with Halachic scholarship. If there is in our ranks some one wise enough to undertake to answer all Halachic questions by return mail, I would not hesitate to relinquish my position as chairman to him.

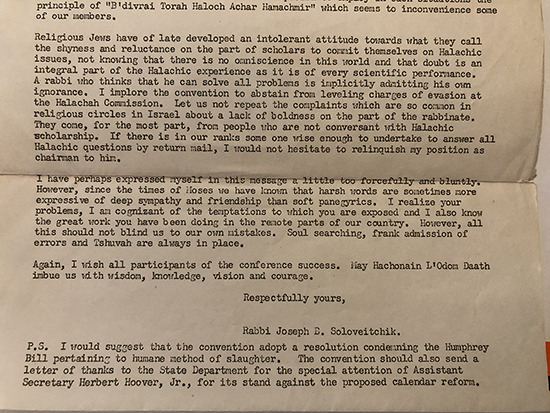

In the last paragraph of the letter, as it appears in Litvin, p. 114, the following words that I have underlined are omitted (and this appears to be a simple mistake rather than an intentional deletion): “I realize your problems, I am cognizant of the temptations to which you are exposed and I also know the great work you have been doing in the remote parts of our country.”

In this case I think that the Rav is speaking to the RCA members as a whole, not to R. Hollander personally.

The P.S. found in the Rav’s letter is also of interest.

P.S., I would suggest that the convention adopt a resolution condemning the Humphrey Bill pertaining to humane method of slaughter. The convention should also send a letter of thanks to the State Department for the special attention of Assistant Secretary Herbert Hoover, Jr., for its stand against the proposed calendar reform.

4. In my previous

post about young rabbis I neglected to mention another such rabbi. R. Yekutiel Yehudah Teitelbaum (born 1912) succeeded his father as rabbi of the town of Sighet, and also as leader of the local hasidic group, at the age of 14.[17]

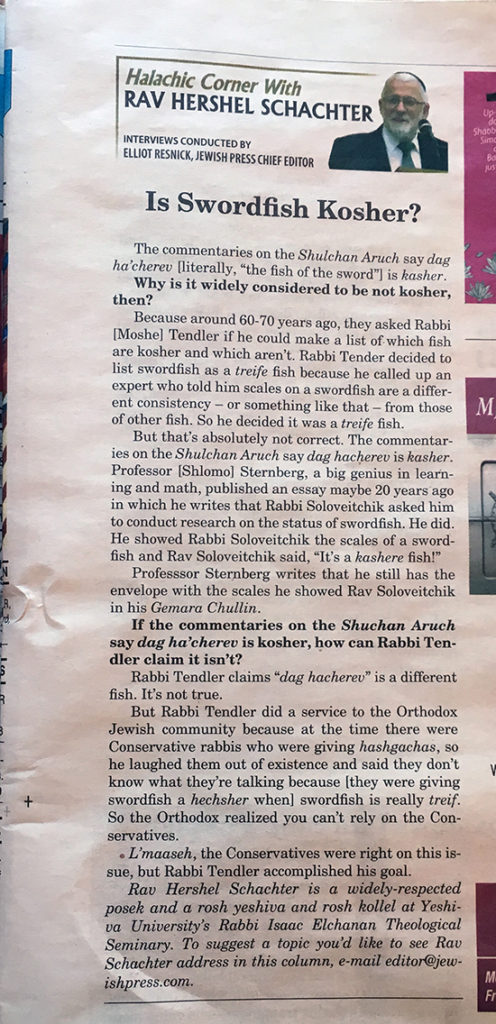

5. In addition to being the posek of the OU, R. Hershel Schachter is also the one Kashrut Vaads all over America turn to for halakhic decisions. That being the case, now that R. Schachter has publicly declared that swordfish is kosher[18] (his private opinion has been known for a long time), how come no Vaads in the United States will certify it as kosher? (In the first half of the twentieth century Orthodox Jews in the U.S. ate swordfish. See my post

here.) Does this mean that in the U.S. the practice of not eating swordfish is for all intents and purposes now regarded as binding, and cannot be overturned even by a great posek?

6. Last summer I spent time in Djerba, Tunisia. I hope to write up my impressions of this amazing community of over one thousand Jews, all of whom are shomer Shabbat. Djerba, and the nearby town of Zarzis which has around a hundred Jews, are the last Arabic speaking Jewish communities in the world. (In Tunis and Morocco the Jews speak French.) Here are some pictures from inside the R. Pinhas Yanah synagogue in Djerba, where you can see the signs in Arabic.

Here is a small learning group in one of the synagogues after ma’ariv. They invited me to participate but not knowing Arabic I couldn’t follow.

When I came back one of my friends told me that I must share one particular story on the Seforim Blog, so here goes. There are fourteen different synagogues in Djerba. After visiting a number of them I noticed that they had no women’s sections. I asked one of the rabbis about the lack of ezrat nashim. He replied, in words that must sound blasphemous to Modern Orthodox ears, “What do women have to do with a synagogue?” While in the U.S. we build “women friendly” mehitzot, so that as much as possible the women can feel part of the synagogue service, in Djerba women’s spirituality has nothing to do with the synagogue. While I later learned that three of the synagogues do have an ezrat nashim, women never attend on Shabbat, only on Rosh ha-Shanah, Yom Kippur, and Purim. The popular Modern Orthodox notion that it is important for women, especially unmarried ones, to attend synagogue on Shabbat is something the women of Djerba know nothing about.

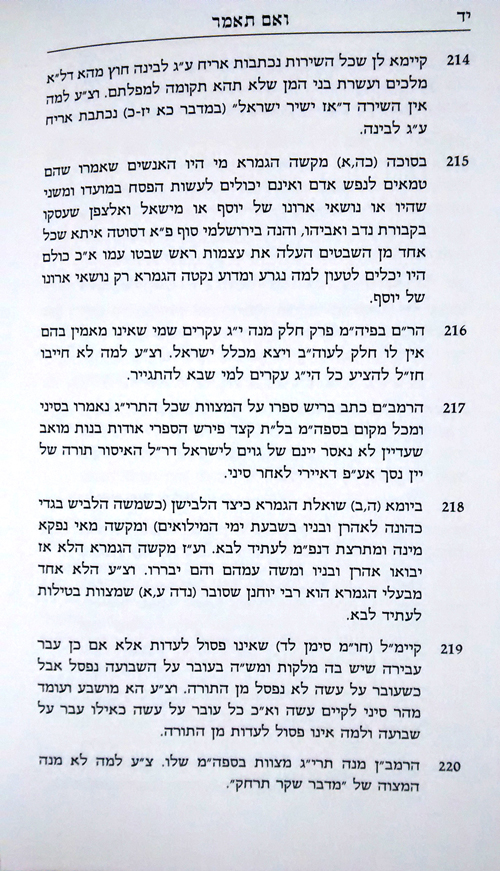

___________