Some recent seforim

By Eliezer Brodt

This is a list of some of the recent seforim I have seen around during my seforim shopping. This is not an attempt to include everything or even close to that. I just like to list a wide variety of works. I note that for some of these works that I can provide a table of contents if you request it, email me at Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com.

א. מסכת קידושין חלק א, מכון תלמוד הישראלי

ב. שו”ת הרשב”א, חלק ג, תשובות השייכים למסכת ברכות וסדר זרעים, מאת חיים דימיטרובסקי, מוסד רב קוק.

This is the much awaited continuation of Dimitrovsky edition of the Rashba. Mossad Rav Kook also reprinted the very sought after first two volumes of this set. On the first two volumes professor Yisroel Ta- Shema writes:

מגוון ההערות משוכלל מאוד, ומאיר עיניים ותורם תרומה יוצאת דופן להבנת סוגיות קשות אלו (הספרות הפרשנית לתלמוד, חלק שני, עמ’ 62).

ג. מגלת קהלת איכה, מהדורת תורת חיים, מוסד רב קוק.

ד. שבלי הלקט, מכון זכרון אהרן, שני חלקים.

This edition contains new notes, the Shibalei Ha-leket Hakotzer and two article of Professor Yakov Spiegel on this work. Unfortunately the parts of this work on Chosen Mishpat and Even Ha-ezer have still not been printed in book form.

ה. שערי דורא עם הרבה הוספות על פי כת”י וכו’ מכון המאור.

An excellent review appears in the most recent issue of Ha’mayan trashing this work, available here.

ו. פירוש ר”י אלמדנדרי על מסכת ר”ה, מכתבי ידות, על ידי ר’ יוסף ברנשטיין, עט עמודים.

ז. פירוש ר”י אלמדנדרי על מסכת מגילה, יומא, מכתבי ידות, על ידי ר’ יוסף ברנשטיין, צד+מג עמודים.

ח. ר’ יעקב צמח, נגיד ומצוה, על פי כתבי יד עם הערות והוספות, מכון שובי נפשי, שמח עמודים.

This book is based on manuscripts but none of the important discussions of Yosef Avivi or Zev Gris were mentioned in the introduction.

ט. זכרון אבות, ר’ אליעזר פואה, תלמיד של הרמ”ע מפאנו, על פי הרבה כ”י, שיח עמודים, עם מבוא, הערות ומפתחות.

Simply put, this work was beautifully done, by the editor Yehudah Hershkowitz.

י. ר’ שלמה תווינא, פ’ שמע שלמה על קהלת, כולל מבוא גדול הערות ומפתחות מ שאול רגב ויעקב זמיר, רעה עמודים.

יא. מאיר השחר, ר’ מאיר סג”ל מליסא, על עניני ברכת התורה וברכה אהבה רבה שפוטרתה, והמסתעף בדיני ק”ש וברכת התורה ובכללי מנין המצות, [נדפס פעם ראשונה בתק”ט] כולל מבוא והערות מאת ידידי, ר’ שלום דזשייקאב, קסב עמודים.

יב. שו”ת צפנת פענח החדשות, כולל שו”ת מכתבים ואגרות, גליונות על שלחן ערוך יורה דעה והשאלתות, תקנה עמודים.

יג. חידושי בעל שרידי אש על הש”ס, חלק ג, פסחים, חולין, עם כמה מכתבים בסוף, תקסב עמודים.

יד. נטעי אד”ם, ר’ דוד מאיר אייזנשטיין, מכון הרב פרנק, כולל ב’ חלקים בכרך אחד, תכד עמודים. חלק א, חידושי תורה ובירורי הלכה, חלק ב, חיבור שלם על יש אם למקרא יש אם למסורות (170 עמודים).

טו. שלחן ערוך אורח חיים חלק ה- מכון ירושלים, הלכות עירובין.

טז. אוצר מפרשי התלמוד, קידושין, חלק ב.

יז. נחל יצחק ר’ יצחק אלחן ספקטור, ד’ חלקים, מכון ירושלים.

יח. יד דוד, ר’ דוד זינצהיים, קדשים, מכון ירושלים.

יט. חידוש רבי ישעיה רייניגר, דרשות’ מכון ירושלים.

כ. מנחת חינוך, בשולי המנחה כרך שני.

כא. יד אלימלך, ר’ דוד אלימלך שטורמלויפר, חידושי ושו”ת עם גדלי גליציה, מכון ירושלים.

כב. תולדות יעקב, ר’ יעקב מאהלער, חידושים על ש”ס, מכון ירושלים.

כג. ר’ אביגדר נבנצל, תשובות אביגדר הלוי, אורח חיים, תקטז עמודים

כד. ר’ אביגדר נבנצל, ירושלים במועדיה, שבת קודש, חלק ג, על ל”ט מלאכות, שמו עמודים

כה. ר’ יעקב הלל, שו”ת וישב הים, חלק ג.

כו. ר’ יצחק דרזי, שבות יצחק, מלאכת בורר, ש+סח עמודים.

כז. ר’ יצחק דרזי, שבות יצחק, דיני יום טוב, קעד עמודים.

כח. כל חפציך לא ישוו בה, שיחות מר’ שמואל אויערבאך, מב עמודים.

כט. ר’ יוסף אפרתי, ישא יוסף חלק ג, או”ח, יו”ד

ל. מחשבת סופר, ר’ ישראל ברוורמן, הלכות בורר, רסה עמודים.

לא. מראות האדם, הל’ עגונות, ר’ אריה דודלסון.

לב. ר’ דוד פלק, בתורתו יהגה, עיוני הלכות בעניני הפטורים והאסורים בתלמוד תורה, [נשים, נכרים, אבלים ותשעה באב, חכמת הקבלה, תלמד שאינו הגון, מקרא בלילה, דבר בשם אמרו ועוד], תקלח עמודים.

לג. ר’ חיים בניש, שערים על הפנימיות, מושגי יסוד בקבלה ובחסידות, על פי ספרי רבותנו גדולי ההגות והמחשבה, ובפרט הספר הק’ שפת אמת, תרסט עמודים.

לד. הרבצת תורה, עצות מר’ שטינמן והגר”ח קניבסקי שליט”א, וק’ מרבה חיים מפסקיו של ר’ חיים פנחס שיינברג, 71 עמודים.

לה. דעת יהודה, תשובות בהלכה ובהנהגה של ר’ יהודה שפירא, מתלמידי החזון איש, רמט עמודים.

This work is full of interesting tidbits. To list one, in regard to the now famous statement of the Chofetz Chaim’s son that he wrote parts of the Mishana Berurah for his father, he writes:

המשנה ברורה כותב בתחילת ספרו כל זה חברתי בעזה”י ופשיטא דזהו אמת ואם נסתייע פעמים בקרוב ודאי עבר על זה בעצמו, וחלילה להכנס בלב מחשבות כאלו. ובהערה שם מביא בשם ר’ חיים קניבסקי שליט”א, שמעתי ממרן החזון איש שאין זה נכון אמנם עזר לאביו אבל החפץ חיים עבר על הכל, ומש”כ שיש סתירות אינו נכון ואין שום סתירה והוא טעה עכ”ד.

לו. שיבת ציון, ר’ אברהם סלוצקי, קובץ מאמרי גאוני הדור בשבח ישוב ארץ ישראל, כולל מבוא והערות, 438 עמודים.

לז. המעין גליון 202, אפשר לראות הכל

כאן.

לח. בר מצוה, אוצר הלכות ודרשות והדרכה לבר מצוה, ר’ משה קרויזר, שפד עמודים

לט. אנציקלופדיה תלמודית, אוצר התפילה, ר’ דוד כהן, 280 עמודים.

It is well known that Rav Dovid Cohen wrote the entry of tefilah for the Encyclopedia Talmudit many years ago. Perhaps he wanted to see it out in some form already, so they printed it as he wrote it then. That is, this work was completed and submitted in 1964. It was edited but no additions were made since its composition in 1964. What is impressive about the work is the amount of sources that he had and used while writing it. Unfortunately the very important topic of tefilah did not have a proper work on it – until now. This recent volume definitely helps one with this huge and extremely important topic, but the information in this work is only based on what had been printed until 1964. However since then there have been many great discoveries related to this siddur and tefilah in general which were not used in this work.

מ. רבבות קודש, ר’ אלישע אלטרמן, מבוא לכל לשונות חז”ל, תרגום אונקלוס, תרגום הכתובים ועוד, סד עמודים.

מא. ר’ אלחן שאף, ברכתא ושירתא, על מסכת ברכות כולל חומר מעניין על עניני הלכה ואגדה מתוך אלפי ספרים, 587 עמודים. בסוף הספר יש ק’ של כמה הערות מהגאון ר’ משה פינשטיין שלא נדפס.

מב. ר’ דוד בן שמעון, שערי צדק,- שער החצר, עניני ארץ ישראל, ב’ חלקים עם הערות.

מג. ר’ יצחק שילת, זכרון תרועה, [ספר מצוין] בסוגיות תקיעות שופר, 706 עמודים. נדפס מחדש.

This special work has been out of print for many years.

מד. ר’ יונה מרצבך, עלה ליונה, תקפב עמודים.

This special work has been out of print for many years as well. The new edition claims to fix typos from the first edition and add in a few pieces. It is annoying that they do not tell the reader which are the new pieces. It is also annoying that they changed around the order of the sefer making it confusing for one when citing a piece. But on balance it’s good that they reprinted this important work.

מה. חכמה פנימית וכמה חיצונית, – חכמת ישראל וחכמת יוון, ר’ צבי אינפלד, מוסד הרב קוק, 247 עמודים

מו. רבי עקיבא ודורו של שמד, מנהגי ימי העומר, ר’ צבי אינפלד, מוסד הרב קוק, 325 עמודים

מז. מילי דחסידותא, חוברת בענין החומרא, קמב עמודים.

מח. ירושתנו חלק ו, מכון מורשת אשכנז, תלה +77 עמודים, [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים

I have heard from many people that they were not excited about this issue compared to the previous volumes. I disagree; I think this volume has some very good articles. The first (seventy pages) article on Tosefos Shantz on Mesechtas Kidushin is a veritable work of art. This author wrote an incredible article on Rashi Nedarim in an earlier volume (4) of this journal. Another article of interest based on some new discoveries is related to the controversy of Pozna about learning philosophy, especially the Moreh Nevuchim. This article continues after the recent article of Professor Elchanan Reiner in the Ta-Shema Memorial Volume. Another article of interest is from Dr. Rami Reiner about various gravestones discovered in Wuerzburg based on his recent work on the topic. Another article I enjoyed was from Profesor Yakov Speigel related to abbreviations and gematriyos. A very special article in this volume was written by Rabbi Hamberger. This article deals with the siddur printed recently called Tefilos Yishurin. In this article Rabbi Hamberger deals with many issues related to siddur and Nussach that have been posed to him due to this edition of the siddur. Another great piece in this journal is Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky’s response to the attack mentioned a while back against him in regard to Panim Yafos being a chassidic work [pdf available upon request]. Another article of great interest written in English is from Rabbi Yakov Lorch about Rabbi Breuer. This article (77 pages) is well researched, gathering much new material focusing especially about this great Gadol’s personality. Just to list some other articles of interest related to the world of Minhag:

– נוסח ספירת העומר הקודם

-מהג ק”ק מגנצא בסדר התפילה ונוסחאותיה

-רווח בין פסוק לפסוק בכתיבת סת”ם

-מנהגי קריאת התורה ביום שמיני עצרת

-ביאור חי העולמים וניקודו

-נוסח חתימת ברכת השכיבנו בלילה שבת

מט. אוריתא, חלק כא [תשע”א], השואה, תרח עמודים, כולל אוסף חשוב על השואה בהרבה תחומים.

נ. בתורתו של ר’ גדליה, מדברי תורתו של הגאון ר’ גליהו נדל, ר’ יצחק שילת, הדפסה שניה עם הוספות, קצט עמודים.

This book sold out as soon as it came out, it has been sought after by many. It was available on the web in different places and then removed from some of them. This work was supposedly never going to be reprinted again as this book was the source of great controversy. However Rav Shilat decided to reprint the book including twenty pages of new material and two more pages of an introduction. In this new introduction he writes that there are many more tapes of Rav Nadel on interesting potentially explosive topics waiting to be printed. One can only hope that they are printed in the near future. Copies of this work are available at Biegeleisen in New York or through me [eliezerbrodt@gmail.com].

מחקר ושאר עינינים

א. שירת הי”ם, שירת חייו של איש ירושלים הרב יעקב משה חרל”פ, 584 עמודים.

ב. חכמי ישראל כרופאים, דוד מרגליות, 222 עמודים

ג. המאסר הראשון, יהושע מונדשיין, מאסרו הראשון של בעל התניא, מאבקי המתנגדים והחסידים בוולינא המלשינויות ומאסריו של הגר”א מווילנא לאור תעודות ומסמכים חדשים גם ישנים, 681 עמודים. This work continues in his famous path, of course he cannot resist attacking R. Eliach and R. Kamentsky on various issues.

ד. משנתו של רבי עמרם, שיחה עם רב עמרם בלויא, מנהיג נטורי קרתא, 176 עמודים.

ה. כלי מחזיק ברכה, עיצוב המשנה כפרשנות, מרדכי מאיר, 120 עמודים.

This work contains some of the articles of Meir related to the mishna topic include:

-הממד הפרשני בניקודן של מילים במשנה

– פיסוק המשנה כפעולת הכרעה פרשנית

– עריכת המשנה כפועלת הכרעת פרשנית

– המשמעות הפרשנית של החלוקה למשניות

-משניות הפותחות פרק בשעה שאמורות היו לחתום את הפרק שלפניהם

ו. גרשום שלום ויוסף וייס חליפת מכתבים 1948-1964 עורך נועם זדוף, הוצאת כרמל, 413 עמודים

ז. על אמונה, על אהבה, וגם על אמנות מחקרים בחכמת ישראל, לאה נעמי פוגלמן, הוצאת כרמל, 220 עמודים, [אוסף מאמרים וכת”י על דברים שונים ומעניינים].

ח. שמות מקומות קדומים בארץ ישראל השתמרותם וגלגוליהם, יואל אליצור, מהדורה שנייה משופרת, 511 עמודים, יד יצחק בן צבי.

ט. וזאת ליהודה, ספר היובל לכבוד יהודה ליבס, מוסד ביאליק, [ניתן לקבל תוכן הענינים.

י. ר’ מנחם פלאטו, רבי יצחק אלחן ספקטור, ספר תולדות חייו, 256 עמודים.

This work does not appear to be impressive comparing it to the other recent Toldot on him printed in the introduction of the volume called Teshuvot Rabbenu Yitzchack Elchanan Spector from Mechon Yerushlayim.

יא. תעלומת הכתר, המצור אחר כתב היד החשבו ביותר של התנ”ך, מתי פרידמן, 288 עמודים

This work came out in English at the same time, the title is The Aleppo Codex. As far as I have seen the two works are identical. Some recent weekly magazines, amongst them Mishpacha (both in Hebrew and in English), printed a nice interview with the author about his new work. The main point of this work is to trace the story of the Aleppo Codex from the riots in Aleppo until today. The book reads like a modern day action thriller and has nice conspiracy theories which might very well be true. I do not want to mention the accusations that he makes at various people, some more of a stretch than others, as I do not want to ruin the book for someone who did not read it yet. All in all it makes for a very exciting and entertaining read.

English titles

1. The Gaon of Vilna and his Messianic Vision, Aryeh Morgenstern, Gefen Press, 446 pp.

2. Collected writings of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, volume 9, 362 pp. This work includes an index of all the previous volumes [Many thanks to Naftoli Lorch for tipping me off about this work and providing me with a copy].

3. Rabbi J. David Bleich, Contemporary Halakhic Problems, Volume 6, Ktav press, 455 pp.

4. Defining the moment of death, understanding Brain Death in Halakhah, Rabbi David Shabtai, 417 pp.

5. In his ways, Reb Dov (Schwartzman), R. Shmuel Wittow, 189 pp.

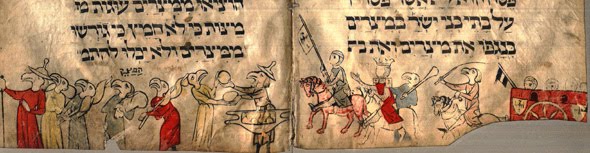

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.