Review of Simon Schama,

The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words, 1000 BCE – 1492 CE by Marc Saperstein

Simon Schama’s The Story of the Jews, covering the period 1000 BCE to 1492 (actually 1497) CE, was for one week (October 5) at the top of the Guardian Bookshop Bestsellers list: a rare achievement for a serious book of Jewish history covering the pre-modern period. It was published in the middle of five one-hour prime-time Sunday evening BBC television presentations, for which Schama was the narrator, recounting his stories from various locations. The first of the five episodes had over 3 million viewers; the series is also being presented in Sweden.

Schama, University Professor of Art History and History at Columbia, is well-known as a serious academic scholar, and his earlier television presentations have made him into an esteemed public intellectual in his native UK. His elegant writing style arouses envy in many of his historian colleagues. This is his first academic encounter with the broad sweep of Jewish history, and the sincerity of his dedication to the project and personal identification with the Jewish past and present is apparent (a strong Zionist commitment was expressed in the television series; the book as well as the series is punctuated with occasional memories of his family and childhood).

Yet, despite the considerable attractions of the man and the book, as a serious work of Jewish history I consider it to be significantly flawed. It is simply too ambitious for someone who, with all his talents, has never published an academic article on any aspect of Jewish history during the period covered by this volume, who shows no evidence of working directly on any of the relevant primary sources in the original languages, and who documents his reliance on the work of other scholars in an inconsistent and incomplete manner, to produce the kind of work that one can recommend as a source of reliable information about “the story of the Jews”.

The presentation is apparently intended for a general readership, yet the material is set forth with the claim of academic authority as a historian. The author frequently appears to speak for the community of academic scholars on a specialized topic, announcing what “we know”, and what “we will never know”. While there are indeed endnotes (a total of 338 for 421 pages), the book is filled with long paragraphs and even full pages replete with detailed information for which there is no hint of the source. Some of the notes include a brief survey of relevant secondary literature, as is conventional in most academic historical writing, but others merely cite a single book title without a page reference. And there are far too many passages clearly taken from the published work of other historians without proper acknowledgment.

The writing style ranges from high seriousness to faux Woody Allen. Some readers will undoubtedly find amusing the frequent reduction of serious matters to a semi-humorous quip; I find this writing technique jarring and inappropriate. A few examples. The “Scroll of the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness” produced by the Qumran community is a work of utmost earnestness about ultimate issues. It contains detailed instructions on the manner of deploying battle squadrons when their full force is mustered, and specific qualifications and tactics for the men and horses of the cavalry, according to leading scholars conforming to Roman patterns of military organization, procedure and strategy. But because it also specifies religious inscriptions on the javelins (e.g. “Shining Javelin of the Power of God”), Schama’s sardonic exegesis is: “We are going to write the enemy into capitulation! Surrender to our verbosity or else!” And because of a brief phrase in the Scroll ordaining that the spears be engraved with a golden depiction of ears of corn, he concludes, “If the Ultimate Battle could only be decided by literary excess and sumptuous schmeckerei [sic] it would be a cakewalk for the Sons of Light”. Is this an illustration of the book’s sub-title: “Finding the Words”? Do such comments enhance our understanding of the apocalyptic eschatological world-view of Qumran?

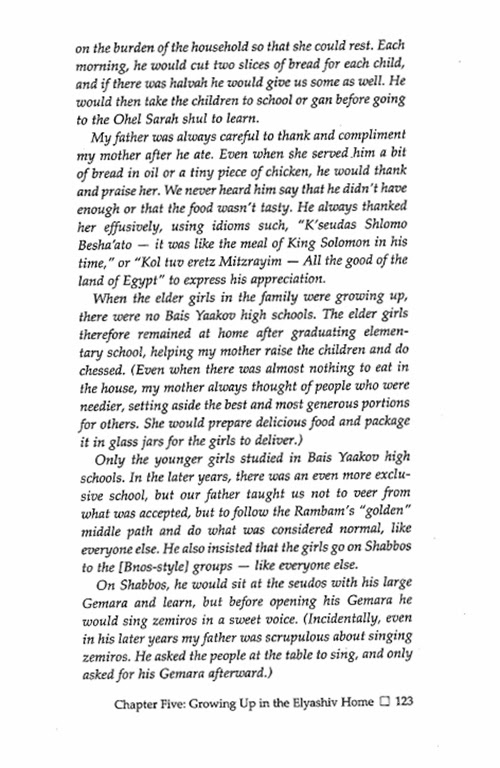

Schama presents several paragraphs of a well-known letter by Moses Maimonides to Samuel ibn Tibbon, discouraging the recipient from travelling from southern France to Egypt on the expectation that Maimonides would have ample time to discuss with him problems relating to Samuel’s translation of the Guide for the Perplexed from Arabic into Hebrew. Maimonides describes extremely taxing his daily schedule fulfilling medical responsibilities in Saladin’s court and then to the Muslim and Jewish population of Fustat, explaining that he barely has time to eat, and no time to study except for a few hours on Shabbat. Most readers will recognize this as a poignant expression of a distinguished physician, currently in poor health himself, devoted to treating others. Schama’s introduction to the text: by writing this letter, Maimonides proved himself to be “a consummate moaner, a king of the kvetch”.

The Jewish Mother trope is introduced fairly early: “The moment you know that Josephus is the first . . . truly Jewish historian is when, with a twinge of guilt, he introduces his mother into the action.” Were none of the authors of Judges, First and Second Samuel, First and Second Kings, the no-longer extant “Chronicles of the Kings of Israel”,. and “Chronicles of the Kings of Judah”, First and Second Maccabees, who did not mention their mothers, deserving to be called “truly Jewish historians”?. The dated stereotype then runs amok in Schama’s presentation of a letter from the Cairo Geniza.

And, it need hardly be said that the Geniza has its share of grieving Jewish mothers complaining their sons don’t write. One peerless virtuoso of the maternal guilt trip, neglected by her bad boy right through the summer when she expected at least one letter, (was that too much to ask, already?) complained ‘you seem to be unaware that when I get a letter from you it is a substitute for seeing your face.’ Don’t worry, be cheerful, do your thing, whatever, I’m alright, this is just KILLING me. ‘You don’t realize my very life depends on getting news about you . . . Do not kill me before my time’. So alright if you won’t send a letter at least, if it’s not too much bother, Mr Always Busy Big Shot, at least send your dirty laundry, a stained shirt or two, so a poor abandoned mother could summon up her boy’s body and have her ‘spirits restored’. What an artist.’.

The note identifies the source in an article by Joel L. Kraemer, where the letter is presented without interspersing mocking comments. It is undeniably a guilt-inducing letter. But Kraemer provides the context in Muslim society, where the position of the mother without a husband is especially precarious. Schama reduces this to a Borscht Circuit Jewish joke.

The chapters appear to reveal a lack of internal consistency. To start with a technical issue: the general convention of publishing for biblical names is to use the standard forms of classical and most modern biblical translations. Thus we have through much of the book Samuel, Moses, Joseph, Abraham, Judah, Isaac.. Then, without explanation, in the discussion of Spanish Hebrew poets, the names appear in their Hebrew forms: Shmuel, Moshe, Yosef, Ibrahim, Yehudah, Yitzhak. In subsequent chapters, we find the equivalent names Yehudah and Judah on the same page (, and then return to the norm of Solomon, Isaac, Samuel, Abraham, Judah. The Index includes: Maimonides, Moses but Nahmanides, Moshe.

More important is the thematic inconsistency. The first part of the book emphasizes the lives of “ordinary Jews” as reconstructed by scholars from sources based on papyri from Elephantine and Alexandria, funeral inscriptions, archaeological excavations at Dura-Europos and synagogues of the Galilee, Arabic inscriptions about Jewish tribes in the Arabian peninsula, and of course the vast collection of the Cairo Geniza. Yet elsewhere in the book, the emphasis on the “ordinary Jew” seems largely to have disappeared in favour of far more extensive discussions of Herod and Josephus, Hasdai ibn Shaprut, Samuel ibn Nagrela, Moses Maimonides, Moses Nahmanides, while other figures no less significant are all but ignored. “Reb Solomon ben Isaac, known as Rashi”, for example, is given one full sentence and two additional passing mentions.

A second confusing inconsistency lies in his attitude toward historical accuracy. The title chosen is not “The History…” but The Story of the Jews. Yet the major repository of this story during the first third of his chronological range—the Hebrew Scriptures—is barely consulted. A reader who searches in this book for an account of the stories of Samson, Samuel, Saul, Elijah, Jonah may well feel surprised that there is no engagement at all with this material, influential as the stories have been on later Jewish consciousness. The focus of the early chapters is not on narrative but on critical biblical scholarship and on archaeology as tests for the historicity of the accounts in biblical texts written much later than the events they report. Indeed, the third chapter seems to be a major diversion from “the story of the Jews”: of its 32 pages, 17 are devoted to an account of 19th-century English archaeologists of the ancient Near East, leading to what Schama calls “the birthing moment of biblical archaeology in the late 19th century”, with the rest devoted to disputes among Israeli archeologists about the historicity of biblical narratives.

Summarizing one section, Schama writes:

“So this is where we are in the true story of the Jews. No evidence outside the Hebrew Bible exists to make the exodus and the law giving dependably historical, in any modern sense. But that does not necessarily mean that at least some elements of the story—servile labour, migration, perhaps even incoming conquest, might not, under any circumstances, have happened. For some chapters of the Bible story, as we have already seen, if only in the depths of H”

A third inconsistency: whether to present co-existence or conflict with the surrounding culture, the host government and population, as the norm. In places—Schama’s discussion of the Elephantine community and Hellenistic Alexandria, the world of the Dura-Europas synagogue and the mosaic synagogue floors in the Galilee, the Islamic-Arabic culture—he presents what appears to be a workable model of Jewish co-existence with Gentile neighbors based on a sustainable integration of Jewish loyalties and traditions with what they considered to be the best values of the surrounding civilization. Schama appears to reject what Salo W. Baron called the “lachrymose conception” of Jewish history, warning that “we must not make episodes of brutality the norm, for they were not”, that “life for the Jews was not all convulsion and expulsion”.

But elsewhere, and increasingly more so in the treatment of Christian Europe, the presentation suggests that the model of conflict, persecution, Jewish suffering is indeed the norm throughout the ages, pointing toward the denouement of the Nazi “Final Solution”. Unusually oppressive anti-Jewish legislation, which he calls “the great segregation”, was passed at Valladolid, Castile in 1412 (though, as Schama admits: “most of its most draconian restrictions proved impossible to enforce”, and it actually applied to Moors as well as to Jews). After listing all the provisions, he writes, “History frowns on anachronism, but what, the crematoria and the shooting squads aside, in the Nazi repertoire is missing from this list?” It should be needless to say that the systematic mass murder of Jews by Einsatzgruppen shooting squads and death camp gas chambers was the essence of the Holocaust. What relevant point can be made by putting these elements “aside” and suggesting a continuity that is extremely misleading.?

This and many other such passages suggest that the model of continuous persecution, with medieval precedents for the Nazi horrors, trumps the models of co-existence emphasized earlier in the book. [The choice of the first section of chapter 7 entitled “Sacrificial Lambs”— entirely devoted to the theme of persecution by Christians from 1096 throughout the 12th century—to be published as an “Excerpt” on the British newspaper Telegraph website on 2 September, before the book was officially released, signals which part of the book’s message the author considered most important.] [The Timeline provided at the end of the book, lists twenty dates from the period 1000–1500 CE. Two of these dates may be considered neutral: the fall of Cordoba and Saladin’s conquest of Jerusalem; two others led directly to heightened intolerance and oppression: the Almoravid and Almohade invasions of Spain, and proclamation of the First Crusade, The other sixteen are all incidents of persecution: massacres, anti-Jewish riots, expulsions. Not a single positive Jewish achievement is listed in this five hundred year period.

This emphasis on persecution as normative removes the policies of medieval popes and kings from their historical context. It presents anti-Jewish statements and decisions without comparison to policies regarding other deviant groups: Muslim minorities in Christian Spain, Christians deemed by the Church to be heretics, prostitutes, gays. And it ignores to a large extent the examples of Jews and Christians co-existing and interacting through a common vernacular in communities that were not at all violently hostile or shut off from each other. [To take just one example, the work of Joseph Shatzmiller based on archival records of court cases in fourteenth-century southern France revealed that in many cases, Christians requiring loans of capital preferred to take them from Jewish money-lenders rather than from Christians in the same business.]

I will pass over the minor factual errors in the narrative to focus on the presentation of three critical events in the middle of the thirteenth century: the internal Jewish conflict over the philosophical writings of Maimonides, the campaign of the Church against the Babylonian Talmud, and the disputation of Barcelona.

According to Schama (in an extraordinarily imaginative paragraph without a single source provided), the central complaint in the anti-Maimonidean campaign of 1232 to place a ban on Maimonides’ Guide and the first book of Maimonides’ Code (Mishneh Torah), containing philosophical material, was that Maimonides presumed “to uncouple the Mishnah from its cladding in the great richly woven garment of the Talmudic commentaries and supplements, and by setting it forth in naked simplicity, as if it were the entirety of the oral law”, he thereby “made the Talmud appear redundant in the eyes of the Gentile nations.” Thus he had “exposed the Talmud to the malicious questioning of outsiders. He had imagined himself to be giving tonic to the oral law but who, if you don’t mind, had asked him to the bedside of the Talmud anyway?”. Furthermore, by applying Greek reasoning to the holy texts, Maimonides had, as it were “dragged the Talmud into a pagan Temple”. In Schama’s imaginative rendering of a complaint by Maimonides’ opponents, “It had got so bad that any yeshiva boy with a saucy tongue in his head could quote half-digested gobbets of Rabbi Aristotle as if he were the equal of Rabbi Gamliel and Rashi, may they rest in peace!”.

The relevant Hebrew texts, written in a rather difficult rhymed prose by those in the anti-philosophical camp and their opponents, were printed already in the 19th century, and there is a significant academic literature discussing these texts. Spinoza summarized the position of one of the opponents (Judah Alfahar) in the fifteenth chapter of his Theological-Political Treatise. But Schama’s treatmentshows no evidence of having consulted any of this material. The reader is given no clue of the actual issues involved, such as:

• whether studying non-Jewish texts or even philosophical texts written by Jews has a proper place in the Jewish educational curriculum;

• whether allegorical interpretation of Bible and Talmudic aggadah is legitimate,

• whether the commandments were given for reasons that can be discerned rationally;

• whether the ultimate reward of eternal existence in the presence of the divine was to be earned through the strict performance of the commandments or through cultivation of the intellect.

Instead we are told that the attack on Maimonides was for isolating the Mishnah from the rest of the Talmud, an accusation that played no role in the literature of the conflict. The actual controversy was raged over serious matters at the core of Jewish religious identity; to reduce them to “half-digested gobbets of Rabbi Aristotle” does not begin to do justice to gravity of the Kulturkampf.

The other two spectacular events, both of which have abundant source material available in English translations, relate to direct interaction with Christians. First was the trial of the Talmud in Paris in 1240. The official doctrine of the Church was that Jews were to be allowed to live under protection in a Christian realm and observe all the practices of their faith, but with ground-rules that would demonstrate their inferior status. One of these was that Jews must not malign the sancta of the Christianity. But the Talmudic literature contains a handful of statements that clearly fall into this potentially perilous category. When converts to Christianity familiar with the rabbinic literature reported this to Christian authorities, Pope Gregory IX reacted strongly. His mandate was to gather and investigate the rabbinic texts to see precisely what they said.

Schama presents the statements reported by Rabbi Yehiel of Paris in defence of the Talmud in a trivializing, dismissive manner, “rhetorical shadow-boxing”, as if Yehiel faced no serious problem: “

The “Jesus” who was said [in the Talmud] to be standing in boiling excrement in the underworld was not Jesus of Nazareth, or he would have been so identified, for there were many other Jesuses at large in those preachy days (as indeed there were). When Donin [the apostate who served as prosecuting attorney against the Talmud] snorted at the disingenousness of the reply, Yehiel cheekily asked whether or not there were, after all, many Louis in France other than the king. [Pushing the mistaken identity line further he asked in wide eyed innocence whether it was remotely conceivable that ‘Miriam the hairdresser’, who was the object of further insults including the suggestion that she was a harlot, could be the mother of Jesus for no Jew had ever described Mary as established in the beauty business.]” ..

The burning of the Talmudic texts in Paris was the dramatically tragic focus of this section, and Shama dramatizes its pathos. But no mention is made of the subsequent accommodation in the papacy of Gregory’s successors, by which Jews were permitted to continue copying and studying the Talmud, provided that their scribes would eliminate the blatantly offensive statements.

As for the Disputation of Barcelona in which the Jews were represented by Moses Nahmanides (RaMBaN), Schama links it directly with Paris: “Thus it was that in 1240 in Paris and 1263 in Barcelona, the Talmud was put in the dock in a show trial of Judaism, with the objects of extracting admissions of its guilt”. While he continues to note that the Barcelona event did not challenge the very existence of the Talmud, he fails to convey the fundamental difference between the two events: in Barcelona, the Christian disputer, Pablo Christiani, did not ridicule and condemn the rabbinic literature; rather he used it in an attempt to undermine Jewish belief.

Thus the first question accepted by both sides for the formal disputation was: “Whether according to the Talmud, the Messiah had already come”. Arguing the affirmative, Pablo cited a rabbinic statement that on the day the Temple was destroyed, the Messiah was born. Schama’s presentation of the Jewish response—“Look,” said Nahmanides, “I don’t believe much of this stuff myself, and I don’t need to; it’s just catnip for debate”—trivializes what was undoubtedly an anguishing decision. To proclaim publicly that the rabbis of the Talmudic period were absolutely authoritative when they decided about a legal matter, but that these same rabbis could be mistaken on crucial theological matters, and that Jews were required to accept rabbinic law but were free to ignore assertions of rabbinic theology, was to tread on perilous ground.

Nahmanides therefore resorted to a technical distinction: that the rabbinic statement indeed asserted that the Messiah was born, but not that he had come, which meant that he had not begun his active career. But that implied that the Messiah was waiting somewhere on earth, almost 1200 years old. Caught in this intellectual thicket, the following day Nahmanides made two crucial concessions: that the aggadah was not absolutely binding but rather analogous to the sermon delivered by a bishop, and that Judaism did not depend on the doctrine of the Messiah and a messianic age (as Schama puts it, flippantly paraphrasing Nahmanides, “The Jewish Messiah—who by the way was not fundamental to our religion”. . . . Many scholars believe that these concessions did not truly reflect Nahmanides’ own beliefs, but that he was driven to them by the exigencies of the public debate. Little of this poignant drama is communicated in the narrative.

The Story of the Jews: 1000 BCE—1492CE will undoubtedly serve as a popular coffee table book. As a source of authoritative historical information about Jews during this long period, readers will need to turn to such collaborative one-volume works as A History of the Jewish People (1976) or The Jews: A History (2008), in which a small group of scholars—six in the first, four in the second—write surveys of their own period of specialization (note the more modest indefinite article in the title of both). Or to the specialized works so helpfully listed and described in Schama’s Bibliography.

Marc Saperstein, Professor Emeritus of Jewish History at George Washington University, is currently Professor of Jewish Studies at King’s College London, and Professor of Jewish History and Homiletics at Leo Baeck College.