Iggeres Ha’Mussar: The Ethical Will of a Bibliophile

by Eliezer Brodt

A few days ago, the sefer Iggeres Ha’mussar from R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon, was reprinted. What follows is a short review of this beautiful work.

R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon was born in 1120. Not much is known about him but from this work one learns a few more things about him, he was a doctor, close to the Ba’al Ha’meor (pp. 50, 63). R. Yehudah appears to have been working on another work (see p. 46) although it is unclear whether this work was a full work. He also loved his only son R. Shmuel Ibn Tibbon very much and wanted him to succeed him as a doctor and translator of seforim -as Yehudah Ibn Tibbon was famous for his own translations. R. Yehuda ibn Tibbon’s son, Shmuel, refers to his father as “father of translators” as he translated many classics, among them, the Tikun Nefesh of Ibn Gabreil, Kuzari, Mivhar Peninim, Emunah Ve’dais of Reb Sa’adia Gaon, Chovos Halevovos, and two works of R. Yonah Ibn Ganach.

In general, most people do not enjoy reading ethical wills for a few reasons. Amongst the reasons given is that wills, by nature, can be a depressing reminder of death and the like, topics most people would rather not focus on. Another reason given is (and this they say they find applies to many older mussar seforim as well) is people feel the advice is dated and does not speak to them at all. In this particular case, however, the Iggeres Ha’mussar is not a typical will as it does not focus on death at all. Furthermore, although it was written around 1190, over 800 hundred years ago, it is full of valuable advice that speaks to one even today. Besides for all this, there are some interesting points found in this will that are very appropriate for a seforim blog to talk about- specifically, how one should maintain their library.

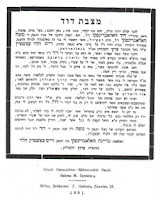

Iggeres Ha’mussar is an ethical will which R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon wrote to his son R. Shmuel Ibn Tibbon. This work has been printed earlier, but not that many times. [1] The most recent reprint is Israel Abrahams’ Hebrew Ethical Wills, originally printed in 1926 and reprinted in 2006, with a new forward by Judah Goldin. Now, Mechon Marah has just reprinted this work based on four manuscripts. This edition also includes over three hundred comments from the editor, R. Pinchas Korach, which explain the text and provide sources for many statements in the book. This new version also includes an introduction, short biography of the author, and a listing of R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon sources. Additionally, this edition also includes a letter from R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon to R Asher M’luniel regarding Ibn Tibbon’s translation of Chovos Halevovos.

Some of the many points found in this work. Regarding learning and other areas of ruchnius R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon writes to his son make sure to learn torah as much as possible, (p. 38), make sure to teach it to your children, (p. 59) to one’s students (p. 61). One should study chumash and dikduk on Shabbos and Yom Tov (id.). R. Yehudah writes to make sure not to waste your youth as at that stage of life it is much easier to learn than later in life (p. 38). He also exhorts him to be on time to davening and be from the first ten for the minyan (p. 67).

He tells his son to study medicine (p. 38). Elsewhere he writes that his son should learn the ibur – how the calendar works (p. 57). R. Yehudah is very concerned, throughout the will, that his son learn how to write clearly and with proper grammar and R. Yehudah offers many tips on how to accomplish these goals (pp. 33-36,45-48). R. Yehudah tells his son to learn Arabic (pp. 34-35) and to do so by to studying the parsha every Shabbos in Arabic (p. 43). R. Yehudah expresses the importance of double checking written material prior to sending it as one tends to make mistakes (p. 45) and notes that “even the Ba’al Ha’meor, who was the godal hador, showed R. Yehudah writings before they were sent out” (p. 50).

On life in general, R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon writes that one should be very careful with the mitzvah of kibud av v’em going so far as to tell his son to review the parsha of Bnei Yonoduv (which deal with this topic) every Shabbos (pp. 62 and 32). He tells him to make sure to seek advice from good people, people whom he’s confident in their wisdom (pg 42). Not to get in to arguments with people, (id.), dress oneself and their family nicely, (p. 43), acquire good friends (p. 39), be careful to eat healthy, (p. 54), and make sure to keep secrets people tell you (p. 70). He advises his son to treat his wife respectfully and not to follow the ways of other people who treat their wives poorly. (p. 57) Later on, R. Yehudah adds to make sure not to hit one’s wife (a unfortunate practice that was all too common in that period, see A. Grossman, “Medieval Rabbinic Views on Wife Beating, 800-1300,” in Jewish History 5, 1 (1991) 53-62) and, if one must rebuke their wife to do so softly (p. 58).

Regarding seforim and libraries R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon writes many interesting things. He writes that he bought his son many seforim which covered a wide range of topics, at times buying multiple copies of the same book in order his son would not need to borrow from anyone else (pg 32-33). He writes that “you should make your seforim your friends, browse them like a garden and when you read them you will have peace” (pg 40 – 41). It’s important to know the content of seforim and not to just buy them (pg 33). He also writes “that every month you should check which seforim you have and which you lent out, you should have the books neat and organized so that they will be easy to find. Whichever book you lend out ,make a note, in order that if you are looking for it you will know where it is. And, when it is returned make sure to note that as well. Make sure to lend out books and to care for them properly” (pp. 60 – 61).

One rather strange point throughout the Iggeres Ha’mussar is the tone R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon uses, the tone leaves the impression that his son, R. Shmuael Ibn Tibbon, was very lax in the area of kibud av (see, e.g., pp. 33, 34, 52). Although, I highly doubt that his son completely failed at honoring his father, one thing is certain that in the end R. Shmuel listened to his father and read and fulfilled the suggestions in the will. Specifically, R. Shmuel became fluent in Arabic and became the most famous translator of his generation, translating many works, the most well-known being the Rambam’s Moreh Nevukim, making his father quiet proud of him in the Olam Ha’elyon.

This new print of the Iggeres Ha’mussar is aesthetically very appealing – the print is beautiful and the notes are very useful. But, this edition, which claims to have used multiple manuscripts, should not be mistaken for a critical edition as it has serious shortcomings in this area. For example, the will many times references the poems of R. Shemuel Ha’naggid’s Ben Mishlei but R. Korach, in this edition, never provides a citation where they are located in Ben Mishlei. This deficiency is in contrast to Israel Abrahams’ edition where Abrahams does cross-reference these external works. The latest edition states that they used four different manuscripts but do not explain what, if any, major differences are between the manuscripts. Nor do they explain the differences with Abrahams’ edition and theirs. The history in the introduction is very unprofessional, quoting spurious sources – this part in too could have been a bit better. Although the introduction includes some nice highlights of the will they should also have included a full index, which is standard in most contemporary seforim. All in all, however, aside for these minor points this ethical will, and this edition, is worth owning and reading from time to time as R. Yehudah Ibn Tibbon wanted his son to do.

Notes

[1] This work was only first published by the famed bibliographer Moritz Steinschneider in 1852. Steinschneider did so as part of a larger work VeYavo Ya’akov el Ha’A”Yan, which Moritz Steinschneider published in honor of his father Yaakov [which is rather appropriate as this will contains much on the obligation to honor one’s parent] reaching age 70. The work was then republished in 1930 by Simcha Assaf under the title Mussar haAv.