R. Shabbtai the Bassist, the First Hebrew Bibliographer

The JNUL has just put up the first Hebrew bibliography, Siftei Yeshenim. This work is written by R. Shabbtai Bass. R. Shabbtai is perhaps most well known for his commentary on Rashi ‘al haTorah titled Siftei Hakhamim.

The JNUL has just put up the first Hebrew bibliography, Siftei Yeshenim. This work is written by R. Shabbtai Bass. R. Shabbtai is perhaps most well known for his commentary on Rashi ‘al haTorah titled Siftei Hakhamim.From Prague, R. Shabbtai, went west, eventually ending up in Amsterdam. It was during these travels he visited numerous libraries and began compiling his bibliography. [Although he did begin the project in Prague, it seems to have really taken off after he left.] In 1680, he published the bibliography in Amsterdam and titled it Siftei Yeshenim the lips of the sleeping ones. This title is appropriate for many reasons. First, it comes from Shir haShirim which has the highest density of book titles, and thus, I think is appropriate for a book listing books. Second, as R. Shabbtai points out in his introduction where he offers ten reasons for bibliography, just reciting the names of books the ignorant can earn a similar reward to those who actually study them. R. Shabbtai based this upon R. Isaiah Horowitz (Shelah).

This work lists about 2,200 titles. Of these, 825 were manuscripts. R. Shabbtai provides an index by category at the beginning of the book. Although the bulk of the lists are books by Jewish authors, he also included about 150 Judaica works by non-Jewish writers.

The work was “updated” in 1806 by Uri Zvi Rubenstein, however, he “demonstrated weak bibliographical abilities and his effort is to be considered a step backwards in the history of Jewish Bibliography.” (Brisman at 13).

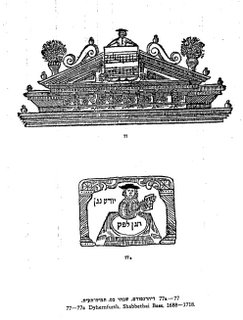

After spending about 5 years in Amsterdam, R. Shabbtai he moved to Dyhernfurth and opened his own press. He began to print works of Polish Rabbis and printed some of the seminal works on Halakha. He printed R. Shmuel b. Uri Shraga’s commentary on Even Ezer, the Bet Shmuel as well as R. Avrohom Abeli’s commentary, Mogen Avrohom.

While he was in Dyhernfurth, he hoped to reprint his Siftei Hakhamim which had been printed in Amsterdam in 1680. He had made extensive corrections and additions which he hoped to include. During the interim, he found out that the publisher in Amsterdam was also readying a reprint and had secured the normal copyright harems. Thus, R. Shabbtai was forced to buy out the Amsterdam printer so he could reprint he own book! This is of particular interest in one’s understanding of copyright under Jewish law. It would seem from this case that the author does not automatically hold a copyright to his own works. Instead, copyright is dependent upon who has a money interest. Unfortunately, none of the many articles or books on Jewish law and copyright cite or discuss this case.

R. Shabbtai’s commentary on Rashi has been reprinted many, many times, and now is standard fare even with Humashim which contain no other commentaries other than Rashi and Onkelos. However, this commentary is typically an abriged version – Ikar Siftei Hakhamim. This abrigment was done by the famed Romm Press in Vilna in the 1872 edition of their Torah Elokim. Although we don’t know for certain who did the abrigment as the title page just allows “two talmdei hakamim” were the ones who did this. It is assumed these would have been editors at the Romm Press. At that time R. Mordechi Plungin was the editor at the press. He was involved with the printing of many “classics” such as the Eiyn Yakkov and the Shulkhan Orakh. In this last book, although he always remain anonymous and never takes any credit for anything he does, he included in Yoreh Deah a few comments under the title Miluim. Now, some don’t like R. Plungin (he was a maskil) most notably the father of the Hazon Ish. Thus, in the Tal-man edition of the Shulkahn Orakh his comments were excised.

So, if one follows that opinion, one should view as important and sensitive task as abriging a commentary with some skepticism. Perhaps, as the editors remained anonymous this hasn’t been noticed – yet. Or, the two talmdei hakamim were not R. Plugin. Be it as it may, R. Shabbtai, the bassist, printer, bibliographer, has left an indelible mark across numerous disciplines.

Sources. For biographical sources, you can look at any one of these as they all just regurgitate what the others prior to them do without adding much, if anything. EJ vol. 4 col. 313. Friedberg, B. History of Jewish Typography of Amsterdam et. al., Antwerp, 1937, 53-64; Y. Rafel, Sinai vol. 8 and 9 reprinted in his Rishonim v’Achronim; and the JE here. See also on R. Shabbtai and Jewish bibliograpy in general S. Brisman, “A History and Guide to Judaic Bibliography.” It is worth reading Zinberg’s nice biography of R. Bass in The History of Jewish Literature, vol. 6, pp. 150-52.

For his printers marks, see Ya’ari, Printers marks. On his Siftei Hakhamim see the new bibliography on Rashi commentary, P. Krieger, Parshan-Data, p. 41-46.

Finally, there is a discussion regarding the first edition of Siftei Yeshanim and why in some edition a Siddur is apended to it. For this, see H. Liberman, Ohel Rochel vol. 1 p. 370-71.