Bridging the Kabbalistic Gap

Nefesh HaTzimtzum by Avinoam Fraenkel

Vol. 1: Rabbi Chaim Volozhin’s Nefesh HaChaim with Translation and Commentary

Volume 2: Understanding Nefesh HaChaim through the Key Concept of Tzimtzum and Related Writings

(Jerusalem: Urim, 2015)

Reviewed by Bezalel Naor

Recently there has been a spate of English translations of the classic of Mitnagdic philosophy, Nefesh ha-Hayyim by Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin (1749-1821), eminent disciple of the Vilna Gaon. This is perhaps the most glorious—certainly the lengthiest—of the translations, one that attempts to rewrite the debate between Hasidim and Mitnagdim.

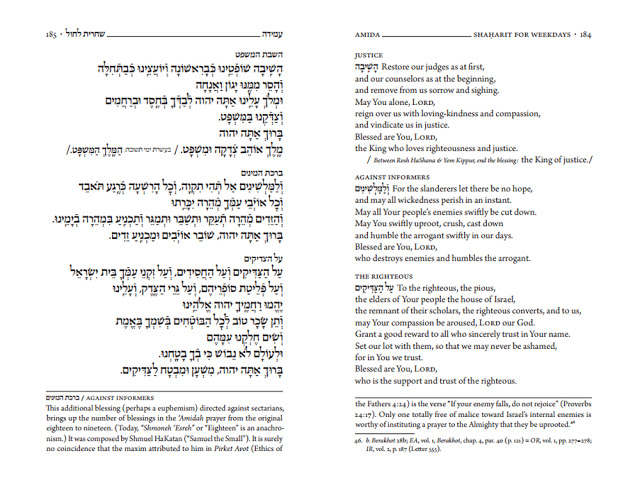

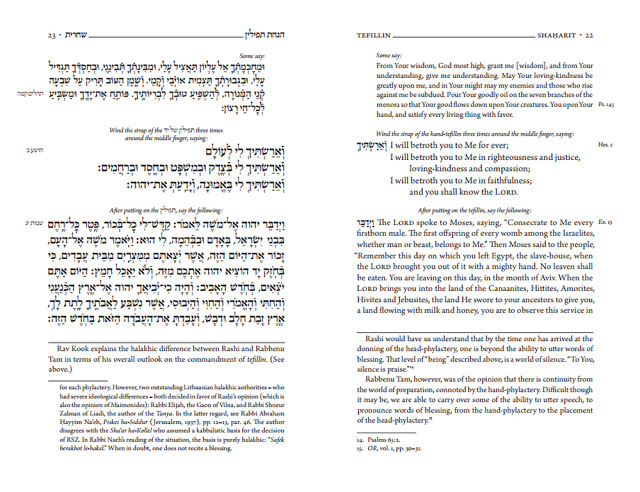

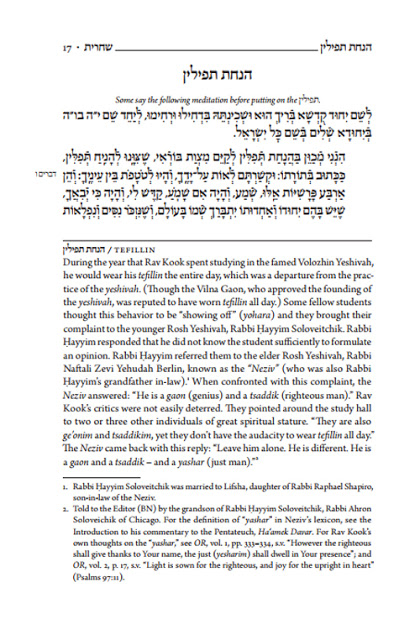

The present edition, the most extensive to date, is divided in two volumes. Volume One consists of a Hebrew-English edition of the entire book with the exception of the famous note by the author’s son, Rabbi Isaac (Itzeleh) of Volozhin, known as “Ma’amar Be-Tzelem.” That note and other related writings of Rabbi Hayyim have been translated in Volume Two. In a unique typesetting innovation, the translator divides the complex Hebrew sentences into phrases, easing the English reading.

In the lengthy introduction to Volume Two, entitled “Tzimtzum—The Key to Nefesh HaChaim,” Avinoam Fraenkel has carved out for himself a most ambitious goal: to tackle the perennial problem of latter-day Kabbalah, namely the Lurianic doctrine of Tzimtzum or divine self-contraction. Traditionally, there have been two schools of thought on the matter: those who hold “tzimtzum ki-peshuto,” i.e. the doctrine is to be taken literally; and those convinced that “tzimtzum she-lo ki-peshuto,” i.e. Tzimtzum is not to be taken literally. As Fraenkel points out, this terminology first gained currency in the debate between two Italian kabbalists, Rabbi Joseph Ergas (author Shomer Emunim) and Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi (author Yosher Levav) back in 1736-7.[1]

Fraenkel’s thesis is that even when things are “pashut” (simple), they truly are not so “pashut” (simple). Even when a kabbalist such as Rabbi Shelomo Elyashiv (author Leshem Shevo ve-Ahlamah) writes boldly that he understands the doctrine literally as did the author of Yosher Levav—that requires complexification.

You might ask of what concern is this rarefied debate to the masses of Jews living in the twenty-first century. Ah! It just so happens that many if not most historians have assumed that this debate, which translates into transcendentalist versus immanentist theology, was at the heart of the terrible controversy between the Mitnagdim and Hasidim that tore apart East European Jewry in the late eighteenth century. At that time, the Vilna Gaon issued a herem, an official rabbinic ban excommunicating the followers of the Ba’al Shem Tov.

If it can be proven that there is essentially no difference of theology between the Tanya (the “Bible” of Hasidism), written by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of the Habad school of Hasidism, and the Nefesh ha-Hayyim (the “Shulhan ‘Arukh” of Mitnagdic ideology), then we will have dissolved any continuing animus between Hasidim and Mitnagdim, and “Shalom ‘al Yisrael” (Peace to Israel). This is the fondest wish of the author.

The truth is—as the author makes us aware—this is not the first attempt to smooth over theological differences between the Tanya and Nefesh ha-Hayyim. On the eve of World War Two, Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler—a preeminent master of the Mussar school, Mashgi’ah Ruhani of Gateshead and later of the Ponevezh Yeshivah in B’nei Berak—then residing in London, wished to issue a proclamation to the effect that there is essentially no mahloket, no difference of opinion between Rabbi Shneur Zalman and Rabbi Hayyim regarding the correct interpretation of Tzimtzum. Rabbi Dessler’s distinguished houseguest at the time was Rabbi Yitzhak Horowitz (known in Lubavitch as “Reb Itche Der Masmid,” on account of his legendary “hatmadah,” or devotion to learning), who acted as fundraiser on behalf of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Joseph Isaac Schneersohn. Rabbi Dessler asked Rabbi Horowitz to sign on the proclamation.

To make a long story short, eventually Rabbi Dessler’s overtures were forwarded to the son-in-law of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (eventual successor to his father-in-law as Rebbe of Lubavitch), who penned a formal reply. For the life of him, Rabbi M.M. Schneerson could not fathom how someone with competence in Kabbalah (which Rabbi Dessler certainly did possess) could fail to see the obvious differences between the Habad and Volozhin understandings of Tzimtzum. (Rabbi Schneerson further outlined that there was a difference between the Vilna Gaon and his student Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin regarding Tzimtzum, a point in the letter which continues to rile Mitnagdim to this day. In fact, Rabbi Yosef Zussman of Jerusalem, eminent disciple of Rabbi Ya‘akov Moshe Harlap, wrote several unanswered letters to the Lubavitcher Rebbe remonstrating how absurd it is to entertain the notion that Rabbi Hayyim, who adored his master the Gaon, disagreed with him on so basic an issue.)

Left without a “partner in peace” of the opposite camp, Rabbi Dessler’s proclamation was buried. Where titans such as Rabbis Dessler and Schneerson could not see eye to eye, Avinoam Fraenkel certainly has his work cut out for him. Before we proceed further to the “nuts and bolts” of the Tanya—Nefesh ha-Hayyim debate, the reader may wish to listen to some music pleasing to the ear:

· When Rabbi Abraham Mordechai Alter, Rebbe of Gur (“Imrei Emet”) asked Rav Kook how he knew so much Hasidut, Rav Kook responded that he had studied Nefesh ha-Hayyim.

· Rabbi Michael Eliezer Forshlager of Baltimore, a foremost student of Rabbi Avraham Bornstein, Rebbe of Sokhatchov (author Responsa Avnei Nezer) carried in his tallit bag a volume which consisted of Tanya and Nefesh ha-Hayyim bound together at Rabbi Forshlager’s special request.

· Once around the family table in Brooklyn, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (by then Lubavitcher Rebbe) spoke so enthusiastically of Nefesh ha-Hayyim that his brother-in-law Rabbi Shemariah Gurary said in jest: “Then perhaps we Hasidim should take to studying Nefesh ha-Hayyim.”

Back to the mahloket. What are the cold facts concerning the debate?

It is incontrovertible that Rabbi Hayyim has stood the Zohar’s terms “memale kol ‘almin” (“filling all worlds”) and “sovev kol ‘almin” (“surrounding all worlds”) on their heads. What for the Tanya is “memale kol ‘almin,” is for Nefesh ha-Hayyim, “sovev kol ‘almin,” and vice versa. Rabbi Shelomo Fisher of Jerusalem has written that this is merely semantics.[2] Others read into the shift of terminology a substantive controversy as to Weltanschauung. What for Hasidism is common experience, namely the immanence, the immediate presence of God, is for Mitnagdism a recondite mystery reserved for the elite.

In the words of Rabbi Eizik of Homel, a major disciple of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi and of his son, Rabbi Dov Baer of Lubavitch (Mitteler Rebbe):

This belief is possessed by all the Hasidim, but the Mitnagdim, even those who are not etc. [the word etc. occurs in the original], do not have this faith, only in a very, very concealed manner, as Israel were in Egypt…They have no room for this faith that Altz iz Gott (All is God).[3]

Fraenkel observes that much of the “poisoning of the waters” was done by publication of a spurious letter attributed to the “Alter Rebbe,” Rabbi Shneur Zalman, in the anonymous Matzref ha-‘Avodah (Koenigsberg, 1858). Later the letter was incorporated in Heilman’s more responsible Beit Rebbi (Berdichev, 1902). In the forged epistle, Rabbi Shneur Zalman writes that it has come to his awareness that the Vilna Gaon understands Tzimtzum literally.

This letter contributed to Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson’s formulation concerning the Vilna Gaon’s view of Tzimtzum. One might mistakenly assume that once the letter is exposed as a forgery, Habad should have no problem accepting that there truly was no disagreement between the two rival camps concerning Tzimtzum. But Fraenkel knows that this is not the end of his troubles.

There is the matter of the passage in the second part of Tanya (titled Sha‘ar ha-Yihud ve-ha-Emunah) which reserves some pretty harsh language for the literalists:

…the error of some wise men in their own eyes, may the Lord forgive them, who erred and were mistaken in their study of the writings of the Ari, of blessed memory, and understood the doctrine of Tzimtzum mentioned there literally, that the Holy One, blessed be He, withdrew Himself and His essence, God forbid, from this world, only that He supervises from above.[4]

Who are the unnamed villains of this passage? To endeavor to answer this question, we would do well to research the printing history of the Tanya. The passage in question was missing from all editions of the Tanya printed before the year 1900. In that year, the passage surfaced in the Romm edition printed in Vilna at the behest of Rabbi Shalom Dov Baer Schneersohn of Lubavitch. Until that time, it had been preserved in manuscript in the keeping of the heirs of the Ba‘al ha-Tanya. That means that for over a century since the Tanya was first printed in Slavuta in 1796, this sensitive piece—a sort of J’accuse, if you will—was suppressed. Why was it ever suppressed to begin with, and why was it finally revealed in 1900?

An obvious solution would be that the passage obliquely lambasted the Vilna Gaon, and it was not until a century later that a direct descendant of the author felt that times had changed and that the sociological “climate” had warmed sufficiently to allow for an unexpurgated version of the Tanya to appear in print. This time, no herem would be issued in Vilna.

And for the record, Rabbi Menachem Mendel was not the first Schneerson to assume that the Gaon understood Tzimtzum literally. Earlier, the Rebbe of Kopyst, Rabbi Shelomo Zalman Schneerson (1830-1900), author Magen Avot, wrote in a letter to Rabbi Don Tumarkin: “This is the entire subject of Tzimtzum, and this is the Hasidism of the Ba‘al Shem Tov and the Maggid, may they rest in peace, that the Tzimtzum is not to be taken literally, as opposed to the opinion of the Mishnat Hasidim [i.e. Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi] and the Gaon Rabbi Elijah, of blessed memory.”[5]

Fraenkel is not willing to accept that the passage in Tanya is directed at the Vilna Gaon or earlier Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi. He stands in good company. Upon receipt of Hayyim Yitzhak Bunin’s Mishneh Habad II (Warsaw, 1933), Rav Kook wrote back to the author requesting that he retract his statement that the pejorative “wise men in their own eyes” refers to the author of Mishnat Hasidim and the Gaon of Vilna.[6]

But then the question remains. Who are the “bad guys” of the Tanya? Fraenkel would have us believe that the reference is to the likes of the crypto-Sabbatian Nehemiah Hiyya Hayyon, against whom Ergas inveighed in his polemical works Tokhahat Megulah and Ha-Tzad Nahash (London, 1715).[7]

If that were the case, the language of the Tanya is too mild and reserved. Sabbatians (believers in pseudo-Messiah Shabtai Tzevi) are usually treated to much more invective, such as “blasted be their bones.” There is a parallel passage in the work of Rabbi Aaron Halevi Horowitz of Starosselje, Sha‘arei ha-Yihud ve-ha-Emunah. There the language is even more compassionate and conciliatory. It is hard to imagine that the Ba‘al ha-Tanya and his prime pupil Rabbi Aaron Halevi Horowitz would show such empathy towards a Sabbatian heresiarch. With very few exceptions, members of the rabbinate were not “melamed zekhut” when it came to deviants of the Sabbatian persuasion. The passage reads:

…As it occurred to some latter-day kabbalists who attempt to be wise (mithakmim)…to understand Tzimtzum literally, as if He contracted Himself, and this is a crime, and their sin is too great to forbear, but their merit is that they have not spoken all these things with premeditation, God forbid, but rather from lack of understanding. May the Lord forgive them, “for in respect of all the people it was done in error” (Numbers 15:26).[8]

Tzimtzum-literalism is not a characteristically Sabbatian posture, nor is it the exclusive domain of Sabbatians. Rabbi Jacob Emden, the arch-nemesis of the Sabbatians, took Tzimtzum literally, drawing an analogy to the vacuum created by a pump.[9] In fact, Emden excoriated Ricchi for belaboring the point, when “certainly, absolutely, it is not to be construed other than literally, and it is one of the a priori assumptions for the believer in our holy religion, if not for anti-religious apikorsim who do not concede the creation of the world.”[10]

There is another problem with deflecting the Tanya’s critique away from the Gaon of Vilna toward Sabbatian kabbalists. If Sabbatians were being targeted, then why did the passage need to be suppressed at all? The Vilna Gaon and his disciples were certainly condemnatory of Sabbatianism in all its guises, so there would have been nothing in the passage to give offense to the Mitnagdim, the opponents of Hasidism.

Fraenkel’s work is much more difficult than that of Rabbi Dessler, for Fraenkel has tasked himself with harmonizing the view of Rabbi Shelomo Elyashiv (1841-1926), author of Leshem, as well. Rabbi Shelomo Elyashiv wrote—both in his Helek ha-Bi’urim and in his recently published correspondence with fellow Mitnagdic kabbalist Rabbi Naftali Herz Halevi Weidenbaum—that he subscribes to the literalist interpretation of Tzimtzum as described in Ricchi’s Yosher Levav.[11] The Leshem went so far as to cast aspersions on the Likkutim printed at the conclusion of Bi’ur ha-Gra to Sifra di-Tzeni‘uta, which present a non-literal reading of Tzimtzum.[12]

Professor Mordechai Pachter was struck by the most incongruous dovetailing of the perspectives of Lubavitch and Leshem concerning the Vilna Gaon’s interpretation of Tzimtzum. Both ascribe to the Gaon a literalist interpretation.[13]

“To cut to the chase,” Fraenkel’s strategy for reconciling what appear glaring differences of opinion involves invoking the kabbalistic theory of relativity, namely the distinction between the divine perspective and the human perspective. The Aramaic expressions that convey this thought are “le-gabei dideh” versus “le-gabei didan.”[14] (In Nefesh ha-Hayyim, the Hebrew terms “mi-tzido”/”mi-tzidenu” serve the same purpose.)[15] This distinction is certainly a valuable tool but it should not be overused. It strikes this reader as overly simplistic to assume that all writers (with the exception of Sabbatians) who grasp Tzimtzum literally are necessarily writing from the human perspective, while writers who understand Tzimtzum non-literally are necessarily writing from the divine perspective. And if the distinction should not be overused, a fortiori it should not be misused. To ascribe the human perspective (as opposed to divine perspective) to Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi when he clearly writes the opposite, is to do violence to his words. A key passage in his Yosher Levav (quoted in fact by Fraenkel) reads:

Therefore relative to us (le-gabei didan), it is as if there was no Tzimtzum and we can say that the Tzimtzum is not literal. However, relative to the Ein Sof (le-gabei ha-Ein Sof) itself, it is literal.[16]

How it is then possible to flip around the author’s mindset and reverse his stated position, is beyond me.

At day’s end, the warring factions within Knesset Yisrael may have to make peace with their differences of opinion intact, even in the matter of Tzimtzum.

[1] Prof. Menachem Kallus confided to the writer that in his estimation the earliest discussion whether Tzimtzum was intended literally or not, is to be found in the notes to Vital’s ‘Ets Hayyim penned by Rabbi Meir Poppers (ca. 1624-1662). Poppers writes that it sounds to him as if Luria’s disciples Rabbi Hayyim Vital and Rabbi Yosef ibn Tabul understood from the Rav [Isaac Luria] that “the Tzimtzum is literal” (“ha-tzimtzum ke-mishma‘o”). See Rabbi Meir Poppers, ’Or Zaru‘a, ed. Safrin and Sofer (Jerusalem: Hevrat Ahavat Shalom, 1986), Sha‘ar ha-‘Iggulim ve-ha-Yosher, chap. 2 (p. 29).

[2] See “Derush ha-Tefillin” in Rabbi Shelomo Fisher, Beit Yishai—Derashot (Jerusalem, 2004), p. 355.

[3] Rabbi Eizik of Homel, “Igeret Kodesh” (Holy Epistle) printed at the conclusion of Hannah Ariel—Amarot Tehorot (Ma’amar ha-Shabbat, etc.) (Berdichev: Sheftel, 1912), 4b.

[4] Tanya II, 7 (83a).

[5] Published in M.M. Laufer, Ha-Melekh bi-Mesibo II (Kefar Habad: Kehot, 1993), p. 286.

[6] Rav Kook’s manuscript was published in Haskamot ha-Rayah (Jerusalem: Makhon RZYH Kook, 1988).

Ironically, Rav Kook’s maternal grandfather Raphael Felman was a Hasid of the Rebbe of Kopyst.

Fraenkel dismisses out of hand the notion that the Tanya pilloried Ricchi because of the fact that references to Ricchi’s Mishnat Hasidim figure prominently in the Tanya. See Nefesh HaTzimtzum, vol. 2, p. 79, n. 89. This argument is unconvincing. It is quite conceivable that the Ba‘al ha-Tanya was fond of Mishnat Hasidim, a popular digest of Lurianic Kabbalah, while viewing Ricchi’s other work Yosher Levav as being outside the pale. And for the very reason that such a venerable Kabbalist erred in his judgment concerning Tzimtzum, he was worthy of compassion. Cf. Rabbi Tzadok Hakohen Rabinowitz:

There were already found many great men, authors among the Mekubbalim, who stumbled in this, including the author of Yosher Levav, who explained the matter of Tzimtzum and similarly many matters of Kabbalah in [terms recognizable] to the understanding [as] total corporealization. I have spelled out his name, for some authors published after him already publicized him in order to clarify his errors in this respect. Behold he was a great and holy man, as is known, and erred only in his faith. Though this too is a great error and requires atonement (as explained above), nonetheless it is not such a grievous sin, as explained in the words of the Rabad…”

(Sefer ha-Zikhronot in Divrei Soferim [Lublin, 1913], 32d)

The reference is to Rabad’s animadversion to Maimonides’ statement in MT, Hil. Teshuvah 3:7 that one who professes belief in a corporeal deity has the halakhic status of a “min.”

[7] Fraenkel’s “Shabbetian Tzimtzum Kipshuto” (as opposed to the “Acceptable Tzimtzum Kipshuto”) strikes this writer as a “straw man” contrived for purposes of pilpul.

[8] Rabbi Aaron Halevi, Sha‘arei ha-Yihud ve-ha-Emunah (Shklov, 1820), Part 1, Gate 1, chap. 21, note (f.51).

[9] Rabbi Jacob Emden, Mitpahat Sefarim (Altona, 1768), 35b-36a (i.e. 45b-46a).

[10] Mitpahat Sefarim 35b (i.e. 45b).

To the question of whether Ricchi himself was a crypto-Sabbatian, I devoted an entire chapter of my book Post-Sabbatian Sabbatianism (1999): “Immanuel Hai Ricchi—Literalist among Kabbalists.”

[11] Rabbi Shelomo Elyashiv, Helek ha-Bi’urim (Jerusalem, 1935), 3a-b. The letters of Rabbi Elyashiv to Rabbi N.H. Halevi Weidenbaum were published in Rabbi Moshe Schatz, Ma‘ayan Moshe (Jerusalem, 2011).

[12] Helek ha-Bi’urim, 5b.

[13] Mordechi Pachter, “The Gaon’s Kabbalah from the Perspective of Two Traditions” (Hebrew), in The Vilna Gaon and his Disciples (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2003), pp. 119-136.

[14] See Rabbi Menahem Azariah da Fano, Ma’amar ha-Nefesh, Part 2, chap. 4 in Ma’amrei ha-Rama mi-Fano (Jerusalem: Yismah Lev, 1997), p. 339; Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi, Yosher Levav (Amsterdam, 1737), chap. 15 (10a), Rabbi Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto, Kalah Pithei Hokhmah (Koretz, 1785), petah 27 (31b); idem, Peirush Arimat Yadai in Adir ba-Marom II, ed. Spinner (Jerusalem, 1988), p. 74; Rabbi Aaron Halevi Horowitz, Sha‘arei ha-Yihud ve-ha-Emunah (Shklov, 1820), Part 1, Gate 1, note to chap. 21 (43b-44a); Rabbi Isaac of Volozhin, “Ma’amar Be-Tzelem” (note to Nefesh ha-Hayyim, Gate 1, chap. 1) in Avinoam Fraenkel, Nefesh HaTzimtzum, vol. 2, p. 397; Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Shemonah Kevatzim (Jerusalem, 2004), 2:120 (vol. 1, p. 284).

[15] Nefesh ha-Hayyim III, 6.

[16] Rabbi Immanuel Hai Ricchi, Yosher Levav (Amsterdam, 1737), chap. 15 (10a). Quoted in Nefesh ha-Tzimtzum, vol. 2, pp. 260-261. See also Fraenkel’s discussion of Ricchi’s position on pp. 63-71.