The Anonymous Author of Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna: An Antinomian or a Radical Maimonidean?

By Bezalel Naor

Today, it is an accepted fact in scholarly circles that Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna form a single unit that postdates the main body of Zohar.[1] More than one reader has been scandalized by statements in Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna likening the Mishnah to a shifhah or maidservant.[2] Predictably, in response, there grew an apologetic literature that attempts to justify how such shocking statements are compatible with normative Halakhah.[3]

One cannot rule out altogether the assertion by various secular historians that these pejorative statements betray an antinomian streak,[4] though to be certain, such statements of Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna are not situated in the present but deferred to the future. With this proviso, they are no more “antinomian” than the statement of Rav Yosef in the Talmud: “Mitsvot (commandments) are nullified in the future.”[5]

I wish to present a hitherto unexplored possibility. It seems likely that the anonymous author of Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna (which surfaced in Spain in the first decades of the fourteenth century)[6] was not so much an antinomian as a radical Maimonidean. It is in this light that we should understand negative statements issuing from the author regarding the study of Mishnah or those comparing the various Talmudic exercises and mental gymnastics to the backbreaking labor to which the Children of Israel were subjected in Egyptian exile.[7] These do not spring from an anti-halakhic mindset but rather from taking at face value Maimonides’ syllabus as laid out in his introduction to Mishneh Torah:

Hence, I have entitled this work Mishneh Torah (Review of the Law), for the reason that a person, who first reads the Written Law and then this [compilation], will know from it the whole of the Oral Law, without having need to read any other book between them [italics mine—BN].

We should be asking ourselves: Are there any historical grounds to assert that in Spain in the early 1300s there were halakhic Jews who openly—we should add, brazenly—promulgated the Maimonidean curriculum to the exclusion of Talmudic studies and the concomitant exercise of pilpul?

I offer the words of Joseph Ibn Kaspi:

Therefore my rabbis, listen to me and God will listen to you! I see that it is the intention of those among you who engage in Gemara, novellae and opinions (shitot),[8] to know proofs for the practical commandments, for you are not satisfied with the tradition from Mishneh Torah composed by Rabbenu Moshe [i.e. Maimonides], though he said: “And one shall have no need of any other book between them [Italics mine—BN].”

Here is an example. Ha-Rav ha-Moreh [i.e. Maimonides] wrote in his laws: “A sukkah that is higher than twenty ammah is invalid.”[9] Yet you despair and are without comfort until you know whether the reason is because “the eye does not rest upon it,” or because “one is not sitting in the shade of the sekhakh (overhead boughs) but of the walls,” or because “the sukkah must be a temporary dwelling,” as written in the Gemara.[10] Even this will not satisfy the very punctilious (mehadrin min ha-mehadrin) until they have added problems and opinions (shitot)[11]: “If you should say,” “one may say,” etc.

Truly, I admit that this is good, but why is the knowledge of proofs an obligation in regard to practical commandments, while not [even] an option,[12] but an outright prohibition when it comes to commandments of the heart? What sin has been committed by these four commandments of the heart (that I mentioned) that you do not treat them in the same manner but are satisfied by a weak tradition of few words, wanting comprehension?[13]

Who was Joseph Ibn Kaspi? Born either in Arles, Provence or Argentière, Languedoc,[14] around the year 1280, he passed in 1345 on the island of Majorca. His was a peripatetic life. The first period of his life was spent in the south of France. Later he gravitated to Barcelona, where his married son David resided. At approximately age thirty-five he travelled to Egypt for several months,[15] hoping to acquire there the intellectual legacy of Maimonides from the Master’s fourth and fifth generation descendants but was sorely disappointed in this respect. He even entertained the thought of traveling to Fez, Morocco in search of wisdom,[16] but that particular journey never materialized.

Ibn Kaspi’s reputation is that of an ultra-rationalist. His naturalistic explanations of events in the Bible far exceed even those of Maimonides; for that reason his opinions were marginalized. Though there is an abundance of manuscripts, it was only in the nineteenth century that Ibn Kaspi’s works were published from manuscript. (A few still remain in manuscript.) To this day, his interpretations have yet to “mainstream.”

My juxtaposing the Maimonidean enthusiast Joseph ibn Kaspi to the anonymous author of the kabbalistic works known as Ra‘ya Mehemna and Tikkunei Zohar may strike the reader of this essai as bizarre. Besides their contemporaneity, what basis is there for this juxtaposition?

Geographically, there are certainly grounds for relating the two authors to one another. Though separated by the Pyrenees, there was much traffic, intellectual and otherwise between Provence and Northern Spain. Some of the greatest families of Provencal scholars originated in Spain: the Kimhis, Joseph and his son David, who excelled as grammarians and Bible exegetes; and the Tibbonides, Judah and his son Samuel, who were the premier translators of classic philosophic works from Judeo-Arabic to Hebrew. And the traffic was two-way. Prominent Provencal families wended their way to Sefarad. The halakhist Rabbi Zerahyah Halevi (“Ba‘al ha-Ma’or”), a native of Gerona, established his career in Narbonne, only to return to Gerona at the end of his days. (His great-grandson was the Talmudist Rabbi Aharon Halevi of Barcelona.)[17] Ibn Kaspi is an example of a Provencal scholar who relocated to Catalonia: Barcelona, and eventually, the Balearic isle of Majorca. Thus, there could easily have been a sharing of ideas between southern France and northern Spain.[18]

In terms of mindset, the border between rationalist philosophy and kabbalah was especially porous at this time. Whoever authored Ra‘ya Mehemna and Tikkunei Zohar, carried with him much Maimonidean baggage. Linguistically, it is apparent to any student of the Ra‘ya Mehemna and Tikkunim that they are rife with the philosophic jargon made popular by the Tibbonides’ translations from Judeo-Arabic.[19] And let us not forget that the very backbone of Ra‘ya Mehemna is an enumeration of the commandments à la Maimonides’ Sefer ha-Mitsvot. (Rabbi Reuven Margaliyot isolated these commandments and presented them in orderly fashion in the introduction to his edition of the Zohar.)

*

When we put it all together it makes perfect sense. As shocking as some of its bold statements may be, the literary oeuvre of Ra‘ya Mehemna and Tikkunei Zohar cannot be construed as issuing from the mind of an antinomian. An antinomian would not go to the bother of constructing a Book of Commandments after a fashion. Rather, I maintain that the downgrading of the study of Talmud in general, and Mishnah in particular, should be attributed to a radical adoption of Maimonides’ curriculum of studies, whereby his halakhic magnum opus Mishneh Torah has superseded the study of Mishnah and Gemara.

In this respect, Maimonides’ devotees in Provence and Spain ventured beyond the Master himself. Maimonides penned a convincing letter to Rabbi Pinhas, the Dayyan (Justice) of Alexandria,[20] that regardless of what he wrote in the introduction to Mishneh Torah, the traditional study of the Talmudic tractates (albeit as summarized in Alfasi’s Halakhot) continues unabated in his beit midrash.[21] The curriculum that Maimonides once proposed remained an abstraction. It seems that Egyptian Jewry was not overly receptive to this innovation. Only well over a century later, did this great intellectual experiment of Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, a “hivemind of halakhah,”[22] designed to replace the “dialectics of Abayye and Rava,” find foot soldiers in the likes of Ibn Kaspi and the anonymous author of Ra‘ya Mehemna and Tikkunei Zohar. They launched their campaign from the soil of Provence and Spain.

Our thesis does not ride on the reputation of Joseph ibn Kaspi. Ibn Kaspi’s statement is perhaps the most outspoken and provocative call for adoption of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah as a way of bypassing Talmudic studies, yet there are other testimonies (from the least expected quarter) that the exclusive study of Mishneh Torah was starting to gain traction in medieval Spain.

The great halakhist Rabbi Asher ben Yehiel (Rosh) emigrated from Germany to Spain at the turn of the fourteenth century and eventually emerged as the Rabbi of Toledo, Castile, where he left his stamp on the shape of Castilian Halakhah.[23] Evidently, Rabbi Asher had cause to fulminate against authorities who decided questions of practical Halakhah based solely on the rulings of Mishneh Torah without recourse to Talmud.

Rabbi Asher writes:

I heard from a great man in Barcelona who was eminently familiar with three orders [of the Talmud, i.e. Mo‘ed, Nashim and Nezikin]. He said: “I am amazed at people who have not studied Gemara and adjudicate based on their reading in the books of Maimonides, of blessed memory, believing that they understand them. I know myself, when it comes to the three orders that I studied, I am able to understand when I read Maimonides’ books. However, his books that are based on Kodashim and Zera‘im—I do not understand at all. And I know that it is that way for them regarding all his books![24]

*

Rabbi Yahya Kafah (1850-1931) was not wide of the mark when he asserted that those statements in Zoharic literature that undercut the Talmud (comprised of Mishnah and Gemara) were designed to enhance the prestige of the Kabbalah. (By the same token, one may safely say that Ibn Kaspi’s desire to streamline the study of Halakhah, stemmed from his valorization of Philosophy.)

Logically, our next question should be: What was Maimonides’ own stake in proposing that his compendium Mishneh Torah take the place of protracted Talmudic studies? Maimonides provides a simple answer to this question in his introduction to Mishneh Torah:

At this time, severe vicissitudes prevail, and all feel the pressure of hard times. The wisdom of our wise men has disappeared; the understanding of our prudent men is hidden. Hence, the commentaries of the Geonim and their compilations of laws and responses, which they took care to make clear, have in our times become hard to understand so that only a few individuals properly comprehend them. Needless to add that such is the case in regard to the Talmud itself—the Babylonian as well as the Palestinian—the Sifra, the Sifre and the Tosefta, all of which works require a broad mind, a wise soul and lengthy time, and then one can know from them the correct practice as to what is forbidden or permitted, and the other rules of the Torah.

On these grounds, I, Moses the son of Rabbi Maimon the Sefardi, bestirred myself…[25]

While perhaps not the ideal curriculum, the exigencies of the time demanded the production of a bold new work on the order of Mishneh Torah that would preserve the practice of Halakhah for the masses ill-equipped to make their way through the labyrinthine discussions of the Talmud or even the decisions of the Gaonica (originally intended to clarify the canons of Jewish Law).

But was there perhaps another purpose of Mishneh Torah that Maimonides kept to himself and was not willing to divulge in writing? In Hilkhot Talmud Torah (Laws of the Study of Torah), Maimonides would proceed to sketch the traditional trivium of Mikra (Bible), Mishnah and Talmud, [26]such that Pardes (the esoteric teachings of Judaism) comes under the rubric of “Talmud”[27]; and that furthermore, the mature scholar who has covered the requisite literature and is thus no longer bound by the daily trivium, “will devote all his days exclusively to Talmud, according to the breadth of his mind and the composure of his intellect.”[28]

Was the condensing of Talmud into Mishneh Torah Maimonides’ master plan to free time for the study of Pardes or esoterica? Should that prove true, then Ibn Kaspi’s interest,[29] and mutatis mutandis that of the Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna, was not so very different from that of HaRav HaMoreh.[30]

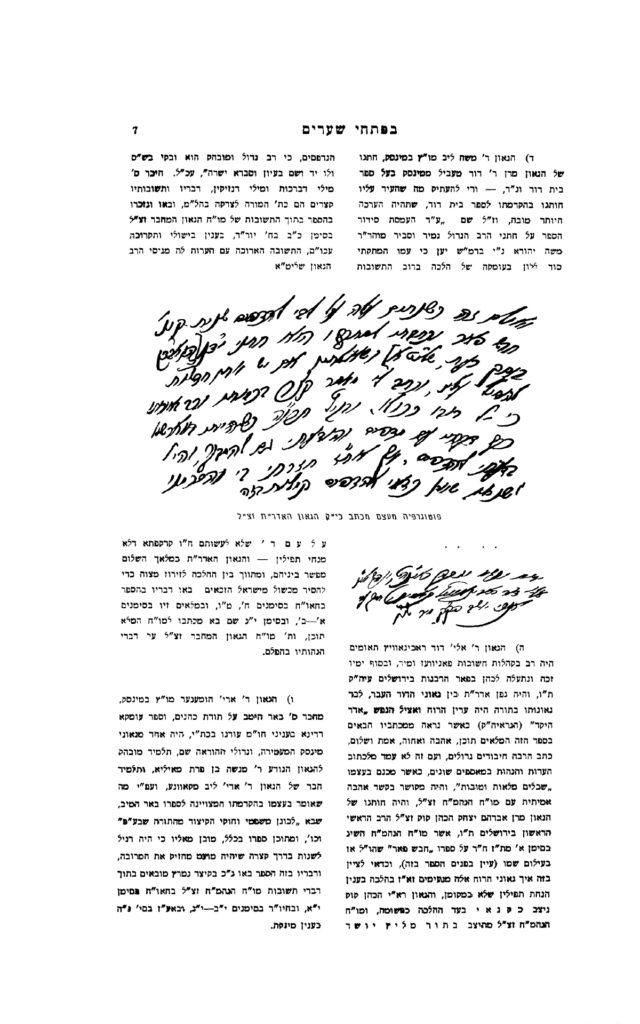

[1] This fact was recognized two and a half centuries ago by the discerning eye of Rabbi Jacob Emden. See Emden’s Mitpahat Sefarim, Altona 1768, Part 1, chap. 3 (6b); chaps. 6-7 (16b-17b); Lvov 1870, pp. 12, 37-39.

Whereas Zohar itself has come to be associated with the name of Rabbi Moses de Leon, no single name surfaces in regard to Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna (though there are some who would attribute the latter to a yet unidentified disciple of De Leon).

It should be mentioned in passing that even in regard to the authorship of the Zohar there has been a sea change in scholarly thinking. Unlike Scholem, who was convinced that the single author of the Zohar was Rabbi Moses de Leon, current thinking (spearheaded by Yehuda Liebes) rejects this notion of single authorship and assumes the Zohar to be a collaborative or composite work on the part of a mystic fraternity or haburah.

[2] See Zohar I, 27b. This is actually a segment of Tikkunei Zohar that the Italian printers in 1558 mistakenly embedded in Zohar. See Editor Daniel Matt’s note to the Pritzker edition of the Zohar, vol. 1 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004), p. 170, note 499. See also the Introduction to Tikkunei Zohar (Vilna, 1867), 15b and gloss of the Vilna Gaon, s.v. shalta shifhah.

And see the Tikkunim appended to Tikkunei Zohar (Margaliyot ed.), tikkun 9 (147a).

By the same token, there are passages where the Mishnah is related to Metatron, the “‘eved” (male servant). See e.g. Ra‘ya Mehemna in Zohar III, 29b; and The Hebrew Writings of the Author of Tiqqunei Zohar and Ra‘aya Mehemna (Hebrew), ed. Efraim Gottlieb (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2003), p. 1, line 3.

Moshe Idel has demonstrated that this motif whereby the Mishnah is juxtaposed to Metatron is to be found in the obscure work of Rabbi Abraham Esquira, Yesod ‘Olam (Ms. Moscow, Günzburg 607, 80a-b). See Idel’s introduction to The Hebrew Writings of the Author of Tiqqunei Zohar and Ra‘aya Mehemna, pp. 23-24, 27-28. Inter alia, Esquira’s text makes mention of “six hundred orders of Mishnah.” This is a reference to b. Hagigah 14a. See Rashi there s.v. shesh me’ot sidrei Mishnah. Thus, p. 23, n. 76 of Idel’s introduction is in need of correction. By the same token, Esquira’s “seven hundred orders of confusion” (“shesh me’ot sidrei bilbulim”) is a parody of the “seven hundred orders of Mishnah” in b. Hagigah 14a. See Idel, ibid. p. 28, n. 105.

Concerning the juxtaposition of the six-lettered Metatron, the servant, to the six days of the work week, see the Vilna Gaon’s gloss to Tikkunei Zohar (Vilna, 1867), tikkun 18 (33b), s.v. be-gin de-Metatron. There is precedent in a Teshuvat ha-Ge’onim (Gaonic responsum) for restricting the activity of the angelic realm to the six days of the week and reserving the seventh Sabbath day for Israel’s sphere of influence. See Tosafot, Sanhedrin 37b, s.v. mi-kenaf ha-’arets zemirot shama‘nu; and Rabbi Reuven Margaliyot, Margaliyot ha-Yam ad locum, and idem, Nitsutsei Zohar to Ra‘ya Mehemna in Zohar III, 93a, note 2.

Later, in sixteenth-century Safed, Rabbi Isaac Luria advised reserving the Sabbath day for the exclusive study of Kabbalah (“as was the custom of the early ones”), while relegating the study of Halakhah to the six work days. This is hinted to in the two verses “Hishtahavu la-Hashem be-hadrat kodesh” (whose initials form the word “Kabbalah”) and “Hari‘u la-Hashem kol ha-’arets (initials “Halakhah”). See Rabbi Hayyim Vital, Peri ‘Ets Hayyim (Dubrovna, 1804), Sha‘ar ha-Shabbat , chap. 21 (103c); Rabbi Jacob Zemah, Nagid u-Metsaveh (Lublin, 1881), 25b. And see Peri ‘Ets Hayyim, Sha‘ar Hanhagat ha-Limmud, s.v. kavvanat keri’at ha-Mishnah (85a): “Know that the Mishnah is Metatron in Yetsirah…”

In the Ra‘ya Mehemna in Zohar III, 279b, the Mishnah is referred to as the “shifhah…the female of the ‘eved, na‘ar (“lad”). “Na‘ar” or “lad” is yet another epithet for Metatron; see b. Yevamot 16b (based on Psalms 37:25) and Tosafot ad loc. s.v. pasuk zeh sar ha-‘olam amaro. Just as Metatron is referred to as “‘eved,” “for his name is like that of his Master” (b. Sanhedrin 38b). Both Metatron and Shadai have the numerical value of 318. (In Ra‘ya Mehemna in Zohar III, 82b it is spelled out that “Metatron is a good servant, a faithful servant to his Master.”)

In Ra‘ya Mehemna, in Zohar III, 276a, three of the most difficult tractates of the Mishnah are singled out for derision, ‘Eruvin, Niddah and Yevamot, as they are assigned the acronym ‘Ani (poor man). The Vilna Gaon points out that the derogation of the rabbis, students of the Mishnah, is not absolute, but only relative to the “ba‘alei kabbalah” (“masters of the Kabbalah”). See Yahel ’Or, ed. Naftali Hertz Halevi (Vilna, 1882), Tetse, 276a, s.v. ve-i teima.

Earlier in that passage (Zohar 275b) we have the underhanded compliment, “Hakham Mufle Ve-Rav Rabbanan” (“Outstanding Sage and Rabbi of Rabbis”), whose initials spell the word “hamor” (jackass). (This cynical remark found its way into the modern mystery novel by Richard Zimler, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon [Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 1998], p. 44.)

One who found absolutely outrageous the labeling of the Mishnah as a “shifhah” was the Chief Rabbi of Sana‘a, Yemen, Rabbi Yahya ben Shelomo (Sliman) Kafah (1850-1931). See his ‘Amal u-Re‘ut Ru’ah va-Haramot u-Teshuvatam (Tel-Aviv, 1914; limited facsimile edition Jerusalem 1976), p. 12. Available at hebrewbooks.org.

‘Amal u-Re‘ut Ru’ah va-Haramot u-Teshuvatam is Rabbi Kafah’s rejoinder to the bans placed upon him by the various batei din (courts) of Jerusalem—Ashkenazic, Hasidic and Sefardic. It struck Rabbi Kafah as highly ironic that he, a staunch defender of Talmudic Judaism, was placed under the ban, while the Zohar, with its numerous derisions of Talmud and its students, was upheld and, what is more, sanctified. Ibid. p. 14.

The constraints of space do not allow us to explore the controversy regarding the Zohar that erupted in Yemen in the early part of the twentieth century between Rabbi Kafah and his disciples, the self-styled Darda‘im, on the one hand, and their opponents, to whom they referred as ‘Ikeshim. (The first label is based on the Midrashic pun on Darda‘ [1Kings 5:11] as Dor De‘ah, “a generation of knowledge”; the second comes from Deuteronomy 32:5, “dor ‘ikesh u-petaltol,” “a perverse and twisted generation.”) At the instigation of his critics, Rabbi Kafah was jailed on more than one occasion by the Muslim authorities. (Rabbi Kafah alludes to this in ‘Amal u-Re‘ut Ru’ah va-Haramot u-Teshuvatam, p. 14.)

The man who acted as a peacemaker between the warring factions was none other than Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook. While upholding Rabbi Kafah’s status as an unusual Torah scholar, Rabbi Kook conveyed to him that he had erred in taking literally passages that were intended to be understood metaphorically. See Igrot ha-Rayah, vol. 2, ed. RZYH Kook (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook 1961), no. 626 (pp. 247-248); Haskamot ha-Rayah, ed. Y.M. Yismah and B.Z Kahana (Jerusalem, 1988), no. 41 (pp. 46-47); Ma’amrei ha-Rayah, vol. 2, ed. Elisha Aviner (Langenauer) (Jerusalem, 1984), pp. 518-521. An incomplete variant of the letter in Haskamot ha-Rayah was published by Rabbi Moshe Zuriel, Otserot ha-Rayah, vol. 1 (Rishon LeZion, 2002), no. 76 (p. 447). See further Rabbi Zevi Yehudah Hakohen Kook, Li-Sheloshah be-Ellul I (Jerusalem, 1938; photo offset Jerusalem, 1978), par. 107 (p. 46).

For Rav Kook’s involvement with the Yemenite community and facilitating their ‘aliyah at the beginning of the twentieth century, see ibid. par. 42 (p. 21); and recently Ben Zion Rosenfeld, “Yahaso shel ha-Rayah Kook le-Hakhmei ha-Mizrah bi-Tekufat Yaffo 5664-5674 (1904-1914)” [“HaRav Avraham Isaac HaCohen Kook and his Attitude Regarding the Sephardi Sages During His Stay in Jaffa 5664–567 4(1904–1914)”], Libi ba-Mizrah (My Heart Is in the East) 1 (2019), pp. 287-290.

[3] See Rabbi Hayyim Vital, introduction to Sha‘ar ha-Hakdamot (printed as an introduction to the standard editions of ‘Ets Hayyim); Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, Iggeret ha-Kodesh (4th section of Tanya), chap. 26 (especially 143a). And see Rabbi Dov Baer Shneuri, Bi’urei ha-Zohar (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot, 2015), Bereshit (to Zohar I, 27b), 5a-8d.

[4] Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews, cited in Gershom G. Scholem, “The Meaning of the Torah in Jewish Mysticism,” in idem, On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (New York: Schocken Books, 1970), p. 70, n. 1.

[5] b. Niddah 61b.

Contra Graetz, Scholem, referring to “the ambiguity of certain statements about the hierarchical order of the Bible, the Mishnah, the Talmud, and the Kabbalah, which are frequent in the Ra‘ya Mehemna and the Tikkunim, and which have baffled not a few readers of these texts,” states categorically: “It would be a mistake to term these passages antinomistic or anti-Talmudic” (op. cit. p. 70). Rather, to describe the peculiar posture of the Ra‘ya Mehemna and the Tikkunim, Scholem coins the term “utopian antinomianism” or “antinomian utopia” (op. cit., pp. 80, 82).

Other secular scholars who objected to Graetz’s judgment concerning the controversial passages in the Zohar (or to be more precise, Tikkunei Zohar) were Bernfeld and Zinberg. See Heinrich Graetz, Geschichte der Juden, 7, Beilage 12; Shim‘on Bernfeld, Da‘at Elohim, Part 1 (Warsaw, 1897), pp. 396-397, note 1; Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature, vol. 3, transl. Bernard Martin (Cleveland: The Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1973), pp. 55-56.

[6] Scholem and Idel would date Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna as early as the end of the thirteenth century (bringing the work in contact with Rabbi Moses de Leon). See Idel’s introduction to The Hebrew Writings of the Author of Tiqqunei Zohar and Ra‘aya Mehemna, pp. 10, 25-26, 29. Tishby established the years 1312-1313 as the terminus ad quem for the composition of Tikkunei Zohar based on its Messianic expectations for those years. Cited in Idel, ibid. p. 10, n. 7. See also p. 23. Idel, relying on Liebes, would make the terminus ad quem a year earlier, 1311. (Ibid.)

[7] See Zohar I, 27a:

They embittered their lives with hard labor (‘avodah kashah)—with kushya (difficulty);

with mortar (homer)—with kal ve-homer (a fortiori);

and with bricks (levenim)—with libun hilkheta (clarification of the law);

and with all [manner of] labor in the field—this is Beraita;

all their labor—this is Mishnah.

Though mistakenly embedded by the Italian printers back in 1558 in the text of the Zohar, this is actually a segment from the later work Tikkunei Zohar. See above note 2.

This same anachronistic interpretation of the verse in Exodus 1:14 is found (with slight variations) in the Ra‘ya Mehemna, again embedded in Zohar III, 153a, 229b (though in this case explicitly identified as Ra‘ya Mehemna). See also Tikkunei Zohar, tikkun 21 (Margaliyot ed. 44a); the additional Tikkunim appended to Tikkunei Zohar, tikkun 9 (147a); and the Tikkunim appended to Zohar Hadash (Margaliyot ed.), 97d (where the end of the verse is interpreted, “be-pharekh—da pirkha”), 98b, 99b.

And see now, The Hebrew Writings of the Author of Tiqqunei Zohar and Ra‘aya Mehemna (Hebrew), ed. Efraim Gottlieb and Moshe Idel (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2003), pp. 39-40.

This degradation of Talmudic hermeneutic was duly noted by Rabbi Kafah (see above note 2). Kafah believed that the not so hidden agenda of the anonymous writer was to promote the study of Kabbalah at the expense of the study of Talmud. See ‘Amal u-Re‘ut Ru’ah va-Haramot u-Teshuvatam, p. 12: “The entire purpose of the author of the Zohar is to cause the Mishnah and the Talmud to be forgotten from Israel, to stop up the mouth of the well of living waters from which flow the ways of the Oral Law, and have them occupy themselves with his new Torah.”

[8] The primary meaning of the Hebrew word shitah is a line; hence, a line of thought. For its derivative usage in medieval rabbinical literature, see Mordechai Breuer, ’Ohalei Torah (Jerusalem: Shazar Center, 2004), pp. 109, 510; Ya‘akov Spiegel, ‘Ammudim be-Toledot ha-Sefer ha-‘Ivri, vol. 2 (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan, 2005), p. 442; and lately, Hayyim Eliezer Ashkenazi, “Heker ve-‘Iyun be-Sifrei Rishonim (4),” Yeshurun, vol. 40 (Nisan 5779), p. 930, n. 7.

In the London Beth Din Ms. 40 (designated in the microfilm collection of the National Library of Israel, F4708), f.30, this word reads “mishnayot,” rather than shitot, but the reading is unlikely, to say the least. Cf. below n. 11.

[9] Maimonides, MT, Hil. Sukkah 4:1.

[10] The three opinions are found in b. Sukkah 2a.

[11] In the London Beth Din ms. for “shitot” there occurs the grotesquerie “shtuyot” (foolishness).

[12] The London Beth Din ms. has the superior reading “eino reshut o makom patur.”

[13] Joseph ben Abba Mari ibn Kaspi, Sefer ha-Mussar/Yoreh De‘ah, chap. 15.

Ibn Kaspi’s Sefer ha-Mussar was published in a couple of collections: Eliezer Ashkenazi of Tunis’ Ta‘am Zekenim (Frankfurt am Main, 1854); and Isaac Last’s ‘Asarah Klei Kesef (Pressburg, 1903). Our particular chapter (15) appeared earlier in the introduction to Ibn Kaspi’s ‘Ammudei Kesef u-Maskiyot Kesef, ed. Salomo Werbluner (Frankfurt am Main, 1848), p. xv. In Ta‘am Zekenim our quote appears on 53a; in ‘Asarah Klei Kesef on p. 70.

Sefer ha-Mussar was written for Ibn Kaspi’s twelve year old son Shelomo residing in Tarascon (Provence). According to the colophon, it was completed in 1332 in Valencia (Catalonia).

[14] Moshe Kahan is of the opinion that Joseph himself was born in Arles, and that it was his ancestors who hailed from Argentière (hence the Hebrew surname Kaspi). See M. Kahan, “Joseph ibn Kaspi—From Arles to Majorca,” Iberia Judaica VIII (2016), pp. 181-192.

[15] Kahan dates the journey between the years 1313-1315, and writes that Ibn Kaspi stayed in Egypt for about five months. Op. cit. p. 182.

In Mishneh Kesef I, ed. Isaac Last (Pressburg, 1905; photo offset Jerusalem, 1970), chap. 14 (pp. 18-19), Ibn Kaspi writes that about two years ago, at approximately age thirty-five, he went down to Egypt. The colophon of the book (p. 168) is datelined Arles, 1317, which would mean that the Egyptian expedition took place about the year 1315.

In Sefer ha-Mussar, which according to the colophon was completed in Valencia in 1332, we receive a slightly different picture. In the introduction, Ibn Kaspi writes that twenty years previous he wandered to Egypt; the total trip, from beginning to end, lasted five months. If we take him at his word, the trip to Egypt was in 1312. What is clear is that the actual sojourn in Egypt was less than five months.

[16] Introduction to Sefer ha-Mussar. In chap. 15, Ibn Kaspi spells out his fascination with Fez: “The Jews find repulsive and abandon today the Guide…the Christians respect and exalt it, and have translated it [to Latin]. All the more so the Ishmaelites; in Fez [italics mine—BN] and other lands, they established study-houses to learn the Guide from the mouth of Jewish scribes.”

[17] See Israel Ta-Shma, Rabbi Zerahyah Halevi (Ba‘al ha-Ma’or) u-B’nei Hugo (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1992), pp. 2, 16; Hayyim Eliezer Ashkenazi, “Heker ve-‘Iyun be-Sifrei Rishonim (4),” p. 933, n. 17.

[18] Though scholars assume a Castilian—rather than a Catalonian—provenance for Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna, I do not see that as a major obstacle. Surely, the main flow of traffic was between Provence in the south of France and Catalonia in the north of Spain, but for Jews, Sefarad was an overarching unity, no matter the local potentates into which it was fragmented. Thus, in 1305, the Rabbi of Barcelona, Catalonia, Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham ibn Adret (Rashba) was able to place a newly arrived German émigré, Rabbi Asher ben Yehiel (Rosh) in the rabbinate of Toledo, Castile. (See Avraham Hayyim Freimann, Ha-Rosh ve-Tse’etsa’av, trans. Menahem Eldar [Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1986], pp. 28-29.)

Sometimes, within a single family one finds both strands of Kabbalah, Castilian and Catalonian. Isaac ibn Sahula, native of Guadalajara, Castile, author of the bestiary Meshal ha-Kadmoni (1281), as well as a kabbalistic commentary to Song of Songs, was a disciple of Rabbi Moses of Burgos, as well as an assumed associate of Rabbi Moses de Leon. (The first reference to the Midrash ha-Ne‘elam, an early stratum of the Zoharic literature, is found in Ibn Sahula’s Meshal ha-Kadmoni.) His brother, Meir ibn Sahula, on the other hand, prided himself on his Catalonian and Provencal pedigree, being a disciple of “Rabbi Joshua ibn Shu‘aib and of Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham ibn Adret (Rashba), who received from Nahmanides, who in turn received from Rabbi Isaac the Blind, son of Rabad of Posquières, who in turn received from Elijah the Prophet.” So writes Meir ibn Sahula at the conclusion to his commentary on the Bahir, “’Or ha-Ganuz.”

(Yehuda Liebes speculated that the especially acerb remarks that precede this peroration are directed against recent developments in Castilian Kabbalah, namely the Zohar. See Y. Liebes, Studies in the Zohar [Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993], pp. 168-169, n. 50. However, in all fairness, the description of those “who expound books and books of the nations, and transcribe therein their gods, and call them ‘Secrets of the Torah’ [Sitrei Torah],” sounds more like an attack on Maimonides and his followers who construe Aristotelian philosophy as Sitrei Torah, than an assault upon the Zohar. At the end of his lengthy footnote, Liebes conceded this distinct possibility.)

Thus, the division of Spanish Kabbalah into discrete units of Castilian versus Catalonian traditions need not prejudice us against the possibility of penetrations and influences that defy this dyadic model. One needs to complexify the general picture of Spanish Kabbalah in order to appreciate the multiplicity of forces at work. Binaries are helpful as historic guidelines but they can never do justice to the complexity of lived reality.

[19] Tishby collected some of these Tibbonide neologisms, starting with “nefesh ha-sikhlit” or “intellectual soul” (Ra‘ya Mehemna in Zohar III, 29b). See Isaiah Tishby, Mishnat ha-Zohar, vol. 1, 2nd printing with corrections (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1949), pp. 77-78.

One can well appreciate how the Chief Rabbi of Sana‘a, Yemen, Yahya ben Shelomo Kafah, a most outspoken opponent of the Zohar, typified its author as “the philosopher, author of the Zohar” (“ha-philosoph mehabber ha-Zohar”). See his ‘Amal u-Re‘ut Ru’ah va-Haramot u-Teshuvatam, pp. 12-16.

Besides the obvious use of Maimonidean terminology, there is the subtle copying of categories. An example would be the way in which the author of Tikkunei Zohar patterned his “hamesh minim” (“five species” or “five sects”) of the ‘Erev Rav (Mixed Multitude) after Maimonides’ “hamishah minim” (“five sectarians”). The passage from Tikkunei Zohar was incorporated by the printers in Zohar I, 25a. (The note in Derekh Emet alerts the reader that the material correlates to Tikkunei Zohar, tikkun 50. In the new Pritzker edition of the Zohar, the passage from Tikkunei Zohar has been removed.) Maimonides’ “hamishah minim” are found in MT, Hil. Teshuvah 3:7. This is just a random sample of the pervasive influence of Maimonides on the author of Tikkunei Zohar and Ra‘ya Mehemna.

Cf. the direct quote from Maimonides, Hil. Teshuvah 3:6 in Isaac ibn Sahula’s Meshal ha-Kadmoni (Venice, 1546), Sha‘ar ha-Rishon (10a), s.v. va-yo’el ha-tsevi le-va’er. And see now Sarah Offenberg, “On Heresy and Polemics in Two Proverbs in Meshal Haqadmoni” (Hebrew), Jewish Thought 1 (2019), pp. 64-65. Recently, Hartley Lachter has attempted to demonstrate that the general tenor of Meshal ha-Kadmoni is esoteric; see H. Lachter, “Spreading Secrets: Kabbalah and Esotericism in Isaac ibn Sahula’s Meshal ha-Kadmoni,” Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 100, No. 1 (Winter 2010), pp. 111-138.

[20] It should be noted, for whatever it is worth, that Pinhas ben Meshullam was a Provencal rabbi who took up the post of Dayyan of Alexandria, Egypt. It would be pure conjecture on my part to posit that his critique of Maimonides reflected the way in which Mishneh Torah had been received in Provence. It is equally possible that Pinhas’ critique was not based on actual observation of the Provencal reception of Mishneh Torah.

[21] See Igrot ha-Rambam, ed. Yitzhak Shilat, vol. 2 (Jerusalem, 1988), pp. 438-439; quoted in Bezalel Naor, The Limit of Intellectual Freedom: The Letters of Rav Kook (Spring Valley, NY: Orot, 2011), pp. 297-298.

[22] The term “hivemind” referred originally to the coordinated behavior of a colony of insects (bees or ants) which to an outside observer, appears the workings of a single mind. In the age of the Internet, it refers to the collectivity of the users who function as a single mind in expressing their thoughts and opinions. This is, in effect, what Maimonides created in Mishneh Torah. As he stated it so eloquently in the introduction to that work:

I…intently studied all these works, with the view of putting together the results obtained from them in regard to what is forbidden or permitted, clean or unclean, and the other rules of the Torah—all in plain language and terse style, so that thus the entire Oral Law might become systematically known to all, without citing difficulties and solutions or differences of view, one person saying so, and another something else [italics mine—BN]—but consisting of statements, clear and convincing, and in accordance with the conclusions drawn from all these compilations and commentaries that have appeared from the time of Rabbenu ha-Kadosh [i.e. Rabbi Judah the Prince] to the present, so that all the rules shall be accessible to young and old, whether these appertain to the (Pentateuchal) precepts or to the institutions established by the sages and prophets, so that no other work should be needed for ascertaining any of the laws of Israel, but that this work might serve as a compendium of the entire Oral Law…

(Moses Hyamson translation with correction)

[23] See A.H. Freimann, Ha-Rosh ve-Tse’etsa’av, chap. 4 (pp. 32-41).

[24] She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rosh 31:9; quoted in Bezalel Naor, The Limit of Intellectual Freedom, pp. 300-301.

[25] Translation of Moses Hyamson with slight alterations.

[26] b. Kiddushin 30a. See Tosafot there s.v. lo tserikha le-yomei.

[27] MT, Hil. Talmud Torah 1:11.

[28] Ibid. 1:12.

[29] In Sefer ha-Mussar, chap. 10, Ibn Kaspi lays out a study plan for his twelve year old son, Shelomo. He advises Shelomo to spend the next two years studying Bible and Talmud. From fourteen to sixteen, he should turn his attention to ethics: Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Avot with the commentary and introduction of Maimonides, Hilkhot De‘ot of Sefer ha-Madda‘, as well as Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Starting at age sixteen, for the next two years, he should tackle the Halakhic codes of Alfasi, Rabbi Moses of Coucy [i.e. Sefer Mitsvot Gadol or SeMaG] and Maimonides, and pursue the study of logic. At age eighteen, he would be well advised to study natural science for two years. Finally, at age twenty, Shelomo should commence studying Aristotle’s Metaphysics and Maimonides’ Guide. (He is also advised to take a wife at that time.)

[30] See Maimonides’ famous parable of the King’s palace in Guide of the Perplexed III, 51.