The Enigma of the Besamim Rosh – Solved by an Amateur – Not!

This person did so and he came up with hits mentioning the Besamim Rosh prior to its publication in 1793. One of these luminaries includes R. Tzvi Hirsch Ashkenazi (Hakham Tzvi). Additionally, he found R. Yehezkiel Landau (according to the CD) quotes the Besamim Rosh and the person points out this should be impossible as R. Landau died the very year the Besamim Rosh was published – 1793. These together, according to this person, demonstrates that people were aware of the existence of the Besamim Rosh prior to R. Saul Berlin’s discovery and thus it is a legitimate work.

Of course, anyone with the most basic familiarity with the Besamim Rosh realize this is a ludicrous claim. Let’s first deal with the Noda B’Yehuda “issue.” First, the year 1793, or more exactly 5553, was a full 12 months and the Noda B’Yehuda died in April some 6 months into the year. Second, there is absolutely no doubt the Noda B’Yehuda was aware of the Besamim Rosh – he in fact gave an approbation to the work! The second approbation given to Besamim Rosh came from R. Saul Berlin’s father, R. Tzvi Hirsch Levin, Chief Rabbi of Berlin.

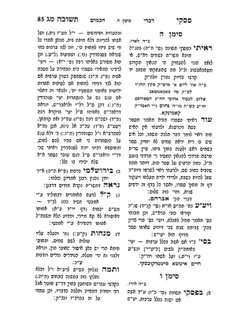

Second, the supposed earlier sources that quote the Besamim Rosh. This claim on its face is astounding as well. The name “Besamim Rosh” was not the actual name which appeared on the manuscript. Instead, this was the name R. Saul Berlin picked. He decided on the name due to the numerical value of Besamim = 392 the same number of responsa which appear in the work (Rosh is self evident). Thus, unless these earlier citation were mind-readers as well, there is no way they could be citing this Besamim Rosh. So, who in fact are they citing? The answer is no one. Instead, this person was unaware the Bar Ilan CD includes notes which appear in the text of the responsa from the editors of the Bar Ilan project! These notes are set off by + signs so that people don’t make this very mistake and think these are part of the text. Thus, for instance, in the case of the Hakham Tzvi the passage in question looks like this:

שו”ת חכם צבי סימן א ד”ה וראיתי להרב

+/רצ”ה לוין/ נ”ב. מיהו גם הרא”ם ז”ל בסי’ כ”ד התיר מטעמים אחרים וכן מצאתי בתשו’ כ”ו דאתי לידי נקרא בשמים ראש (סי’ רע”ו) ועם היות שאין דבריהם מוכרחים מ”מ הא חזינן דנסבי אפי’ שלא במקום מצוה ואין מוחה בידם+

As I mentioned previously, there is no dearth of literature discussing the Besamim Rosh after its publication (see Samet and the sources cited therein) but it is 100% erroneous to claim anyone beforehand was citing to this work.

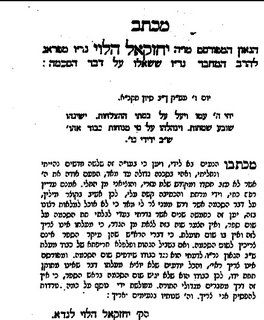

R. Yehezkiel Landau haskamah to the Besamim Rosh (1793)