This Thursday,

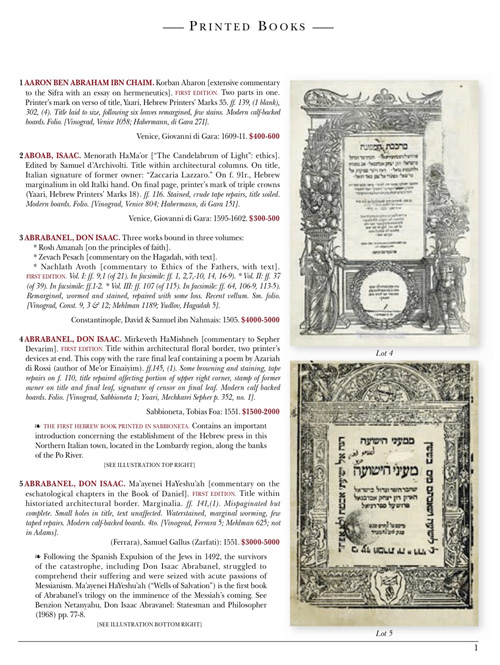

Kestenbaum & Co. is having an auction. The catalog is available

online and the viewing takes place this week. For those interested in some highlights, the website provides those. But, I wanted to highlight a theme that hasn’t been noted. First, a quick background regarding Hebrew book auctions. [Note, this is not a comprehensive attempt.] There are five auction houses that concentrate on Hebrew books, Kestenbaum, Judica Jerusalem, Asufa, Baronovitch, and, a recent entry, Kedem. While all five concentrate on Hebrew books, they are all unique in many ways. First, the catalog. With the exception of Judaica Jerusalem, all offer their catalogs online. Additionally, they also offer them in hard copy format through subscriptions. Kestenbaum and Baronovitch are American auction houses, while the others are Israeli. Of the two American, Kestenbaum has auctions more frequently. Both American typically have two to three hundred lots, while the Israeli ones have as many as 800. The Israeli ones provide illustrations for every lot and descriptions in Hebrew and English (although, at times, the English translations can be very poor). Kestenbaum doesn’t have illustrations for every lot. Which gets us to our hidden theme. In the lots that provide photos of the title pages, many title pages carry a mythological or Christian theme. Of course, we are not suggesting that these were selected because of this theme, instead, we are merely pointing it out.

Mythological Title Pages

The first illustration is for lot # 4,

Mirkeveth ha-Mishna Abrabanel’s commentary to Devarim. This edition of Sabbioneta, 1551 (the first Hebrew book published there), carries the illustration of

Mars and

Minerva.

This is not the only time this title page appears. Indeed, in this auction catalog’s illustrations it appears on three other illustrated books. See lots 171, 191 and 217. That is, these other books share the same title illustration. Marvin Heller, in his article discussing this title page explains that, as one probably surmised, this title page with its mythical theme, first appeared in non-Jewish books. Beginning in 1523 this title page was employed in a variety of non-Jewish books. It would be our book, Mirkeveth ha-Mishna, that would be the first Hebrew book to re-use this title page. Heller, traces the subsequent history in his article for those looking for more information on this title page. Marvin Heller, “Mars & Minerva on the Hebrew Title Page,” in Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 98:3 (Sept. 2004).

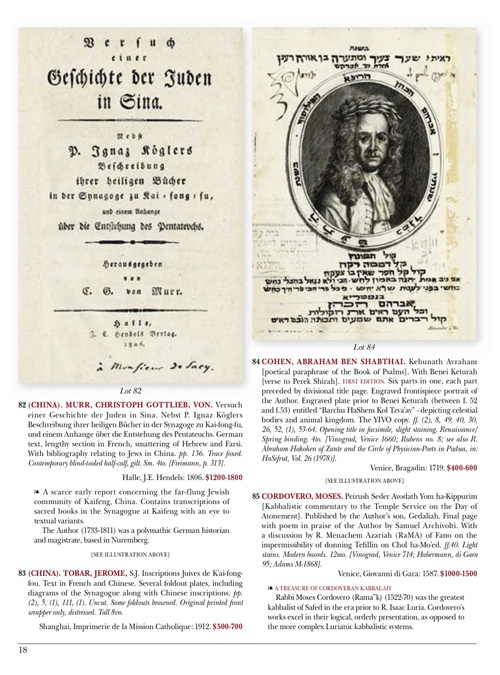

The second illustration related to mythological theme is that of lot # 221,

Pirkei Rebi Eliezer, Sabbionetta, 1567. This title page shows

Hercules striking Hydra the multi-headed snake (the illustration seems very similar to that of

Antonio del Pollaiolo’s “Hercules and the Hydra.”).

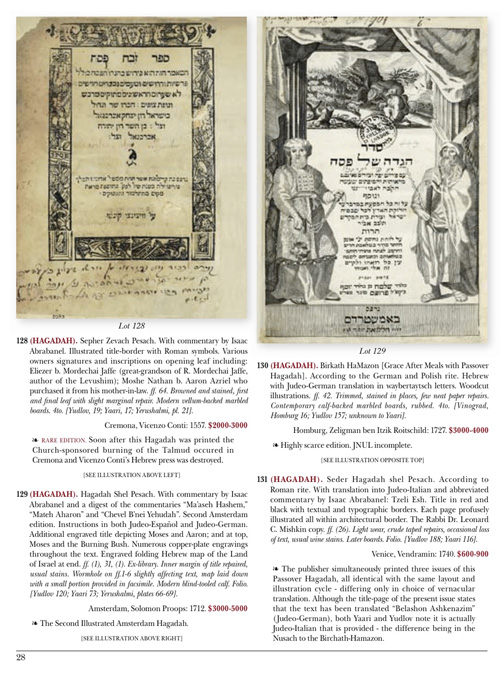

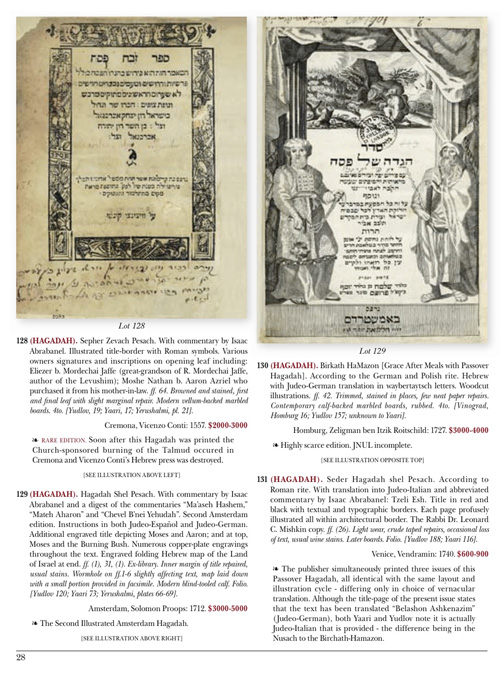

We now turn to the Christian title page. This one is from lot #129, Haggadah shel Pesach, Amsterdam, 1712. The title page, at the top, depicts Moshe at the burning bush. This Haggadah, which is known as the Second Amsterdam Hagaddah due to it being the second edition of the Haggadah to carry copperplate engravings rather than wood. These engravings were done by a convert, Abraham ben Jacob (whose name was removed from the title page in this edition). Ben Jacob used a well known Christian engravers illustrations as models for the Haggadah illustrations. So, Moshe at the burning bush illustrations is almost the same, with the exception that the triangle surrounding God’s name (depicting the Trinity) is removed in the haggadah. Both appear below.

Yerushalmi, in Haggadah and History, shows other examples of borrowing in this Haggadah.

It is worth noting a few more benign title page illustrations that appear in this catalog. The first is that of lot #165,

Amudei Golah, Cremona, 1556 that shows in the center a medallion personifying Cremona, while in the “upper section is the head of a winged horse, with a bare-breasted woman to the right and a man to the left.” Marvin Heller,

The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book, p. 417.

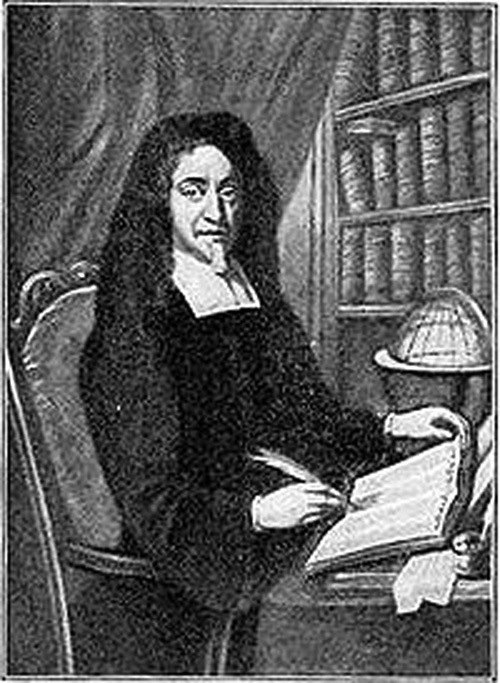

Finally, we get to the last book we shall discuss, one of the earliest to include a portrait of the author on the frontispiece, lot 84, Kehunat Avraham, Venice, 1719. Additionally, one can see that he is wearing a wig, not all that uncommon amongst the Rabbinic sect for the period of time it was universially fashionable. For example, R. David Neito is shown with a wig, as are others. One well known example of one who skipped the wig was R. Yehudah Areyeh Modena, who appears in his portrait completely bald.