On Libraries, Bibliophiles & Images: Taj Auction 13

On Libraries, Bibliophiles & Images: Taj Art Auctions 13

by Eliezer Brodt and Dan Rabinowitz

Taj Art Auctions will hold its 13th auction this Sunday, April 7th (the catalog is available here). The auction contains many items worth highlighting, especially those related to historic Jewish libraries, as well as other unique books and ephemera.

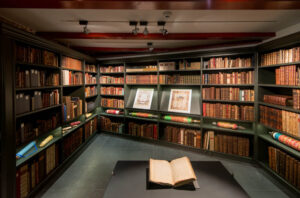

Recently, arguably, the most significant Jewish library reopened its doors. The National Library of Israel, housed at Hebrew University for decades, moved into its own building, designed by the starchitects Herzog & de Meuron, who count the Tate Modern among other outstanding projects. Books are integral to the Jewish experience, and the library’s location, next to some of the most important institutions of the Jewish state, the Knesset, the Israel Museum, and the Supreme Court, echoes that sentiment. The library’s ground floor houses the Jewish Studies reading room, which contains over 200,000 volumes. The library itself holds over four million books (and counting). These are now accessed by a quartet of robots that fetch requested books. There is even a window to watch them in action. The Scholem room has been transformed from its small, cramped quarters into a spacious room that houses the collections of several kabbalah scholars. Scholem’s desk is still present. There is a permanent exhibit of some of the library’s treasures, but that is only accessible on an official tour.

Nonetheless, it is undoubtedly worth seeking out. An exhibition of manuscripts of one the greatest privately held collections of Judaica, the Braginsky Collection, opens this month. While the National Library’s new building and collection are exceptional, many precursor Jewish libraries existed throughout the Jewish diaspora.

The oldest functioning Jewish library in the world is the Ets Haim Library in Amsterdam, dating from 1616. (An exhibition of its books was held at the National Library of Israel, then known as the Jewish National and University Library, in 1980). Its antiquity is tied to the date the school opened with the same name. This school became well-known for its unique curriculum and success in imparting that curriculum. Unlike the Central and Eastern European schools that almost immediately started studying Mishna and Talmud, the Talmud Torah applied a more systematic approach to Jewish literature. R. Shabbetai Seftil, the son of R. Yeshaya ha-Levi Horowitz (Shelah or Shelah ha-Kodesh), traveled from Frankfurt to Pozen via ship. That journey took him through Amsterdam, where he saw that the students’ studies operated in sequence. First, they studied the entire corpus of Tanakh and then completed the Mishha, and when they matured, they only began studying Talmud, and this approach contributed to their unique success. Seeing the benefits, he broke down crying, “Why don’t we follow the same approach in our countries [of Central and Eastern Europe]? Suppose only we could institute this throughout the Jewish communities. What would the harm be in first completing the Torah and Mishna until the student reaches thirteen and then begins Talmud? With that background, it will take only a year to become proficient in the intricacies of Talmud study, unlike our current approach that requires years to reach that level of fluency.”

In an example of the intertwining nature of the library and the school, the bibliographer R. Shabbetai Bass (1641-1718), who wrote the first Hebrew bibliography, Sifte Yeshenim (today, most well-known for this commentary on Rashi, Sifte Hakhim). Bass was born and lived in what is today the Czech Republic (Czechia). Around 1680, he went to Amsterdam to print Sifte Yeshenim. During that time, he visited the library and school and described the students as “students of giants: young children dancing like locusts and like so many lambs. To my eyes, they were giants, so well-versed in their knowledge of Torah and grammar. They could write Hebrew verse and poetry in meter and converse in clear Hebrew.” He also describes the unique aspect of the library. “Within the midrash, they have a special school, and there they have many books, and all the time they are in the yeshivah, this room is also open, and whoever wishes to study, anything he desires is lent to him. But not outside the beit midrash, even if he provides a large sum of money.”

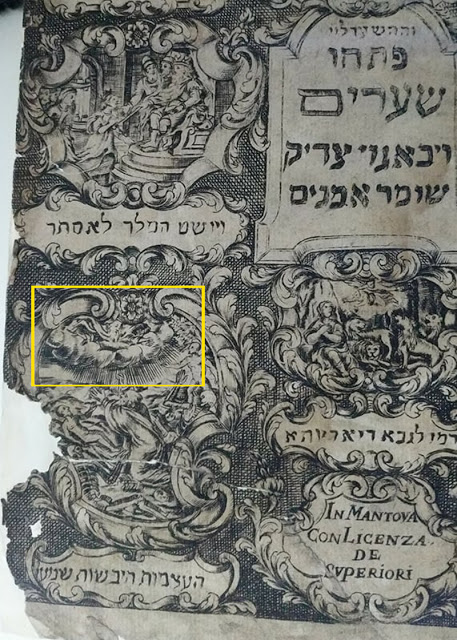

Among the Ets Hayim Library treasures is an Amsterdam print, the first Haggadah with copperplate illustrations. While illustrations in printed Haggados began with the Prague Haggadah of 1526, these were woodcuts. Copperplates, however, produce much finer illustrations. In 1695, the convert, Abraham ben Yaakov, designed and executed these copperplates, and the Haggadah was printed by the famed Amsterdam publisher, Proops. (Copperplates were already used in printing decades before the Haggadah. Perhaps one of the most significant recent examples is a 1635 copper etching by Rembrandt that the Jewish art scholar Simon Schama donated to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam last year.) The illustrations are based on the Christian biblical illustrations of Mathis Marin. While most are innocuous, the temple image at the end of the Haggadah is topped with a cross. In addition to the fine illustrations, the Haggadah also contains a large foldout map of the Jews’s journeys from Egypt to Israel; it is among the first Jewish maps of the Holy Land.

The Ets Hayim Library holds a unique edition of this Haggadah, considered one of its most treasured books. First, it contains an extra title page. But, more importantly, it is hand colored. While the copperplates are a significant improvement, the coloring makes this an especially striking Haggadah. It is listed among 18 Highlights from the Es Haim: The Oldest Jewish Library in the World, published by the library in 2016. The book includes three full-page reproductions of various details of the Haggadah and smaller reproductions of other pages. There are only two other copies of this version. One is at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and the other is being auctioned at Taj Art Auctions (lot 89). The copy at the auction was a gift from the printer Solomon Proops.

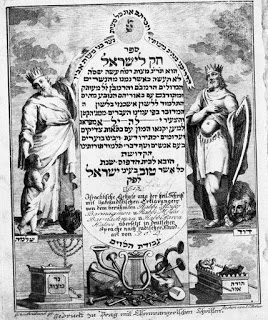

Similar images from the Haggadah’s title page were reused in Menoras ha-Me’or, Amsterdam, 1722, (lot 84), and the Amsterdam Haggadah final illustration of the Beis ha-Mikdash, that if one looks closely, the Christian cross was left intact from the original Mathis Marin illustration, also appears in the beautiful and unique title page adorning Birkas Shmuel, Frankfurt, 1782 (lot 152).

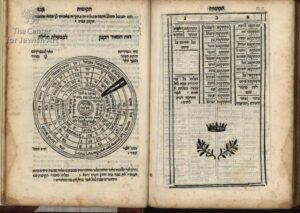

Amsterdam was home to another significant library, the Rosenthaliana. It was collected in Hanover but eventually landed in Amsterdam. The catalog related to this library attests to the rarity of another book in this auction. This library was amassed by Eliezer (Leeser) Rosenthal (1794-1868). Born in Warsaw, he eventually traveled to Hanover, where he served as a Rabbi. His wife came from a wealthy family that allowed Rosenthal to indulge in his passion, book collecting. At their death, his library comprised more than 5,200 volumes, including twelve incunabula and numerous rare and unique books. After his death, his son, George, commissioned the bibliographer Meyer (Marcus) Roest to complete a bibliography of the library. It was published in two volumes in 1875 and reproduced in 1966. Roest’s work incorporated Rosenthal’s catalog of his library, Yodeah Sefer. Despite the many rare books in the collections, there was at least one book he could not procure, at least a complete copy. In his entry, 1524, for the Ibbur Shanim, Venice, 1679, he says that “it is a terrible loss, that my copy is incomplete, it is missing the last pages, my copy ends at page 95 … and is missing the calendric charts for 150 years, beginning from 1675, my copy is missing from 95 of these charts, from 1731 onward… This is a scarce (yekar mitzius) book and is not listed in R. Hayim Michael’s [Or Meir] or the Shem ha-Gedolim, or Di Rossi’s bibliography.” The National Library of Israel received a complete copy from the Valmaddona Trust, which was digitized and available online. (One can bid on four of the Valmadonna books, Talmud Bavli, Seder Zeriam, Lublin, 1618, lot 70 , as well as lots 12, 54, and 68). A complete copy of the book appears in the auction at lot 2. (For more on calendar books, see Elisheva Carlebach, Palaces of Time: Jewish Calendar and Culture in Early Modern Europe, and pp. 51-55 regarding Ibbur Shanim. His work is also a source for the Tu be-Shevat seder, see our post, “Is there a Rotten Apple in the Tu be-Shevat Basket“). The book has its own intersting history that is briefly described in the timely post, “Kitniyot and Mechirat Chametz: Paradoxical Approaches to the Chametz Prohibition.”

Yet another seminal Jewish library was that of R. Dovid Oppenheim (1664-1736), considered “the greatest Jewish bibliophile that ever lived.” (See Alexander Marx, Studies in Jewish History and Booklore, 213). Oppenheim started his rabbinic career in Moravia, moved to Prague, and was eventually elevated to Bohemia’s Chief Rabbi. At age 24, his library consisted of 480 books, and by 1711, his library stood at over 2,100 books, missing only 140 books from those listed in Shabbetai Bass’s bibliography of all Hebrew books. After his death (with some additions from his son, Yosef), the library rose to 4,500 printed books and 780 manuscripts. Although Oppenheim lived in Prague, the library was in Hanover. This was due to the heavy book censorship, which included the potential for confiscation by the authorities. Oppenheim visited his library, but perhaps because his time was limited, his works do not indicate that he was acquainted with the book’s contents. Instead, he should be considered a consummate bibliophile, and his collection consisted of rarities and special beautiful and unique copies, with a considerable number on blue paper. For example, there were 51 books printed on vellum, 40 of which he commissioned himself, out of about 200 known books printed on that medium until 1905.

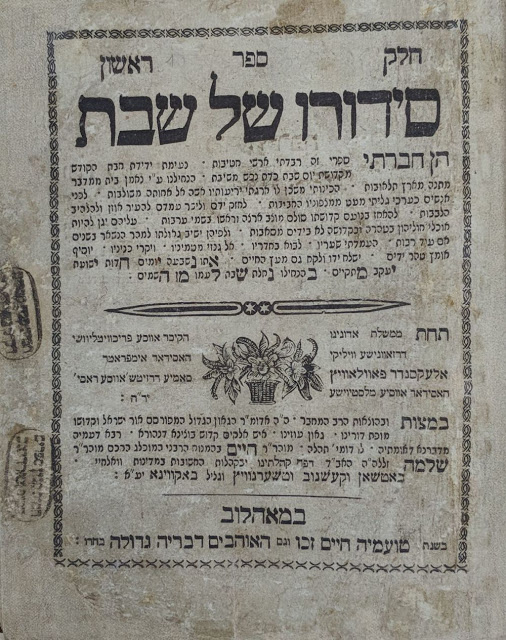

After his death and multiple attempts to sell the library, it eventually went to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. A complete history of the library was most recently accounted for by Joshua Teplitsky in his Prince of the Press: How One Collector Built History’s Most Enduring and Remarkable Jewish Library. But before its final resting place, there were a handful of catalogs of the library or various aspects of it. The first complete printed catalog of the library was issued in 1782 and was intended to elicit interest from potential Jewish and non-Jewish buyers. Thus, it contains two title pages, one in Hebrew and the other in Latin. This rare bibliophilic item is lot 156.

Finally, the auction also includes books from the library of R. Nachum Dov Ber Friedman, the Sadigur Rebbe. His library was recently described in Amudei Olam by R. Zusya Dinklos, pp. 419-39. Aside from traditional works, the library also held Haskalah works, as the one in lot 71.

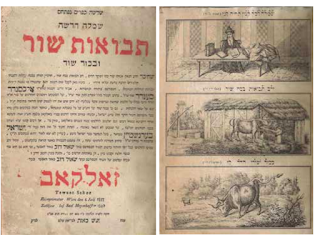

Illustrated Books

We discussed Ibur Shanim, and in addition to its rarity, it is also among the small number of Hebrew books that contain illustrations. Because the book’s purpose was to elucidate and explain Hebrew calendrical calculations, including the determination of the tekufos (which he vehemently criticizes some Rishonim and others for dismissing them as old wives tales), there are a handful of tutorial images.

Gross Family Collection

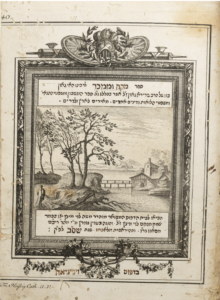

Likewise, Sefer ha-Ivronot, Offenbach, 1722 (lot 73) includes celestial images, in this instance, a movable wheel of the heavenly apparatuses. While there was some speculation that the title page image depicting a heliocentric universe was deliberately to align with the book’s contents, that is unlikely as the image was reused in at least three other books printed in Offenbach that are unrelated to astronomy.

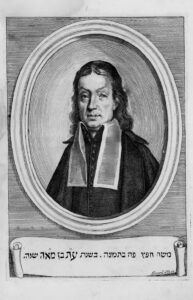

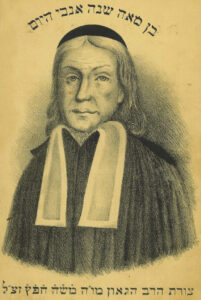

Moshe Hefetz, perhaps more well-known for the 19th-century modification of his portrait attached to the first edition of his Melechet Machshevet, which depicts him bare-headed, authored a book on the Bet ha-Mikdash, Haknukas ha-Bayis, 1696, (lot 20), within which several Temple elements are illustrated.

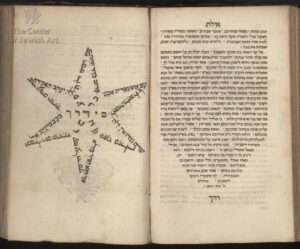

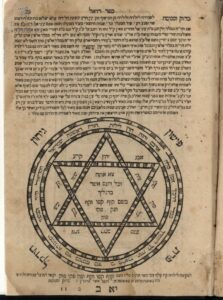

Two books contain eclectic images of the Jewish star. Igeret Ayelet Ahavim, Amsterdam, 1665 (lot 140) and the first edition, 170 Amsterdam, Raziel HaMalach, (lot 120) include unusual adaptations of the star. (For another kabbalistic rarity, lot 116, is the kabbalist, Rabbi Yosef Erges’ personal copy of the Rosh ha-Shana and Yom Kippur machzorim with his kabbalistic additions.)

From the Gross Family Collection

From the Gross Family Collection

There are a handful of artistic title pages, with at least two Greek gods, Hercules and Venus (see lots 10 and 48), and some potentially objectionable ones that Marc Shapiro discussed in his book Changing the Immutable (lots 64 & 78).

One of the most unusual title pages is a special one that its owner inserted into the book. The title page, taken from a non-Jewish architectural image by the 18th-century engraver Franz Carl Heissig, was filled in by hand with the book’s publication information (lot 5).

Finally, while censorship in Jewish books is somewhat common, undoing censorship is less common. Lot 62 is a unique copy of the Shu’T Maharshal that includes the otherwise expunged name of an informer. Other copies only refer to the person obliquely; this copy, although crossed out, the name is still visible. For more on this see Elchanan Reiner, “Lineage (Yihus) and Libel: Mahral, the Bezalel Family, and the Nadler Affair,” in Elchanan Reiner, ed., Maharal: Biography, Doctrine, Influence, 101-26 (Hebrew).