Leket Yosher – A Closer Appraisal in Light of a Recent Controversy

The Leket Yosher was compiled by R. Yosef ben Moshe (1423-c.1490), a student of R. Israel Isserlein (1390-1460), the author of the Terumat HaDeshen. The Leket Yosher records R. Isserlein’s customs and rulings. The Leket Yosher was the first work to base itself on the four part division of the Turim, however, only the sections on Orach Hayyim and Yoreh Deah are extant. While it appears that there was a third part on Even haEzer which is no longer extant, it is unclear whether there ever was a part on Hoshen Mishpat. [1] Leket Yosher [2] was not published until 1903 (Orach Hayyim; and in 1904 Yoreh Deah was published) by R. Ya’akov Freimann from Munich manuscript in R. Yosef’s own hand.[3] It has been published at least three times and today is typically available as part of a set of three minhagim works, Leket Yosher, Yosef Ometz and Noheg KaTzon Yosef.

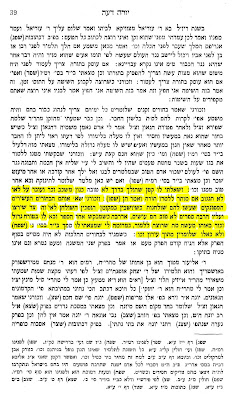

The passage used by some in the discussion in Or Yisrael regarding ArtScroll, records the disapproval of R. Isserlein of the practice of “spoiled, rich kids” who used a revolving table to avoid having to get up and get a book. (vol. 2, p. 39). The passage reads in full:

“אותם הבחורים העשירים המפונקים שעשו להם שולחנות כשיושבין במקומן הופכין השולחן לאי זה צד שירצו ועליו הרבה ספרים לא טוב הם עושים, אדרבה כשמבקש אחר הספר ובא לו בטורח גודל זכור באותו מעשה מה שרוצה ללמוד, כמדומה לי שמצאתי לו סמך ב[יורה דעה] בסימן ג’ (שפח) ‘ולא כאלו שלומדין מתוך עידון’ וכו”

“Those rich, spoiled students that had made a revolving table which allowed for them to turn the table to get which ever book they wanted [without having to get up] such behavior is inappropriate. Instead, one who gets up to get a book and exerts themselves will remember that they had to look for the book [and will remember what the book said]. It seems to me [R. Yosef] that support for this position [that frowns upon the turntable] can be found in Yoreh Deah where it says “one should not study in luxury.'”

Similarly, when the Vilna Shas was printed many years ago, the story goes that the printers said that whoever finds a mistake in this heavily invested shas will get rewarded. In the excellent book, Derech Etz Chaim (p. 568) about R’ Isser Zalman Meltzer, they record a story that a printer of a current Yerushalmi visited the Steipler with the idea to print a Yerushalmi in a similar format to the Talmud Bavli and to have, amongst other things, many commentaries in the back. When the Steipler heard this, he said that R. Meltzer used to complain that there’s a very big printing mistake in the Vilna Shas. Specifically, that in the Vilna Shas many commentaries in the back, but each commentary is 3 pages so you have to look 50 times for the same thing. R Isser Zalman wanted that they should put it in order of the Blatt, so he recommended that they not make the same mistake and do the same for the Talmud Yerushalmi.[4]

“ושאלתי לו קטן שהולך בדרך לא טובה כגון משכב זכר ועובר על לאו לא תגנוב אם מותר ללמדו תורה ואמר הן”“And I asked [R. Isserlein] a student who sin, with sins such as homosexuality or stealing should they be taught Torah? Answer, Yes.”

Since we are on the topic of the Leket Yosher it is also worthwhile to point out some of the other interesting observations related to the Leket Yosher. Perhaps the most important fact to come from the Leket Yosher is that the assumption, first espoused by the Taz and expanded upon by others, that the Terumat HaDeshen was not the product of actual questions and answers and instead R. Isserlein made up the questions himself and therefore, according to some, the Terumat HaDeshen is not authoritative. As R. Freimann demonstrates, however, this is incorrect. Instead, actual events as recorded in the Leket Yosher can be matched with teshuvot in the Terumat HaDeshen thus demonstrating that the questions in Terumat HaDeshen were based upon actual events and were not fabricated.[5]

Since we are on the topic of the Leket Yosher it is also worthwhile to point out some of the other interesting observations related to the Leket Yosher. Perhaps the most important fact to come from the Leket Yosher is that the assumption, first espoused by the Taz and expanded upon by others, that the Terumat HaDeshen was not the product of actual questions and answers and instead R. Isserlein made up the questions himself and therefore, according to some, the Terumat HaDeshen is not authoritative. As R. Freimann demonstrates, however, this is incorrect. Instead, actual events as recorded in the Leket Yosher can be matched with teshuvot in the Terumat HaDeshen thus demonstrating that the questions in Terumat HaDeshen were based upon actual events and were not fabricated.[5]

Perversely, the criticism of the Terumat HaDeshen was turned on its head and applied to the Leket Yosher. Specifically, the Sanzer Rebbi in his Divrei Yatziv (E.A. 39), claims that one cannot rely upon the Leket Yosher as it records actual events and one cannot decide halakha from events. This is inapposite of those who complain that the Terumat HaDeshen is not reliable because the questions do not relate to real events. It appears that the position of the Sanzer Rebbi has not been accepted as R. Moshe Feinstein (which is especially noteworthy in light of his general disapproval of newly discovered works), R. Ovadiah Yosef, Daayan Weiss, R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach and many others all cite with approval the Leket Yosher. Moreover, the Sanzer Rebbi himself is at least five other places[6] in Divrei Yatziv cites with approval the Leket Yosher. In only one other instance does he couch his citation of the Leket Yosher (E.A. 78) with a disclaimer “that is is unclear whether the Leket Yosher is reliable.”

Other interesting comments in the Leket Yosher include: R. Yosef, in 1456, records that he saw Halley’s Comet [7] (vol. 2, pp. 17-8), R. Isserlein used to tell Torah riddles on the first days of Pesach and Shavous and Purim (vol. 1, pp. 103-4), R. Isserlein’s daughter-in-law, Redel, studied Torah (vol. 2, p. 37), and the restriction against walking behind a woman is no longer applicable (id.).

Notes:

[2] Aside from being unique in it use of the Turim’s division, the Leket Yosher, has another unique attribute. As Professor Y.S. Spiegel has pointed out the title employed, Leket Yosher, hints not only to the authors own name (as is a a somewhat common practice – see Spiegel for more on this practice) but also to R. Yosef’s teacher, R. Isserlein as well. Specifically, the numerical value of Leket Yosher and is ישראל יוזלין Yisrael is for R. Isserlein Yozlin is for Yosef. See, Y.S. Spiegel, Toldot Sefer haIvrei, vol. 2 p. 411.

[3] For additional biographical and bibliographical information see generally Freimann’s introduction. For some reason neither R. M.M. Kasher in Sa’arei HaElef or Glick in Kuntres HaTeshuvot HaHadash or in the earlier version by Boaz Cohen has an entry for Leket Yosher.

[4] It is, however, worth pointing out that R. Isser Zalman Meltzer held that part of ameilus batorah is getting up a taking a sefer out of the bookshelf. Thus he would never allow anyone to get him a sefer. He would get it himself. According to R’ Shach explained that there were 2 reasons for this. One is because he didn’t want anyone to help him, and two because of his ameilus batorah.

Likewise, in the same book (p. 181) they record that R. Aharon Kotler uses the Gemara in Menochot where Avumy forgot something that he said. He turned to his talmid R. Chisda to remind him how he explained a certain topic. The gemara asks why he didn’t send his talmid to come to him. Rashi says that it’s because of yegata u’motzasa (he worked and he found). R’ Aharon deduces that going yourself is part of the learning.

In an effort to avoid having to get up to get books R. Teichtel writes to his father R. Yissachar Teichtel, author of Am habonim Semacha, that when R. Yissachar visited R. Menachem Zemba, he had sitting on the table in front of him, a gemara with Rambam and all of chazal so that way he wouldn’t have to waste time and get up every time he needed to look up something. (letters in Tal Talpios, mentioned here, on page 44).

R. Meir Bar-Ilan, in a beautiful chapter of his classic MiVolozhin l’Yerushalayim (p. 269), in describing how his uncle, the R. Yechiel Michel Epstein, author of the Arukh HaShulhan, wrote his work said that R. Epstein also had a Rambam, shas and Shulchan Orach on the table and reference everything without having to move.

See also the comments of R. Munk in Pa’as Sadecha, who specifically rejects the notion that the Leket Yosher is not a reliable work. Instead, R. Munk states that the Leket Yosher was written with extreme care and can be relied upon.

In the newest edition of the Terumat HaDeshen, edited by Shmuel Avitan (Jerusalem, 1991), the editor is completely dismissive of R. Freimann. Although Avitan neither mentions Freimann by name nor explains why Freimann is wrong. This attitude is particularly striking in that R. Freimann devotes some 50 pages to an extensive and well documented introduction of the Leket Yosher as well as related topics. Avitan, on the other hand, is satisfied with a two page introduction that adds almost nothing to either the Terumat HaDeshen the work or R. Isserlein the person and in fact borrows heavily, many times without citation, from R. Freimann’s introduction. [It appears Avitan was not even aware of Dinari’s work.] For example, Avitan deals with when R. Isserlein refers to “one of the great ones – אחד מהגדולים” if R. Isserlein is referring exclusively to the Maharil. Freimann was the first to demonstrate that this reference is not exclusive to the Maharil. Avitan, also comes to the very same conclusion, without mentioning Freimann or even as Avitan is wont, “the introduction to the Leket Yosher.”

Aside from claiming that the responsa are fictional, others have made a distinction between the “teshuvot” and the “pesakim” of R. Isserlein. See Dinari, Hakhme Ashkenaz, p. 303-4 n. 223.

[6] Divrei Yatziv Orach Hayyim nos. 179, 236, 295, 297; Yoreh Deah 31.

[7] For a later mention of seeing a comet see Glikel Zikhronot, ed. C. Turnyanski, Jerusalem, 2006, p. 605 n. 314.