Another “Translation” by Artscroll, the Rogochover and the Radichkover

Marc B. Shapiro

1. As I discuss in Changing the Immutable, sometimes a choice of translation serves as a means of censorship. In other words, one does not need to delete a text. Simply mistranslating it will accomplish one’s goal. Jay Shapiro called my attention to an example of this in the recent ArtScroll translation of Sefer ha-Hinukh, no. 467.

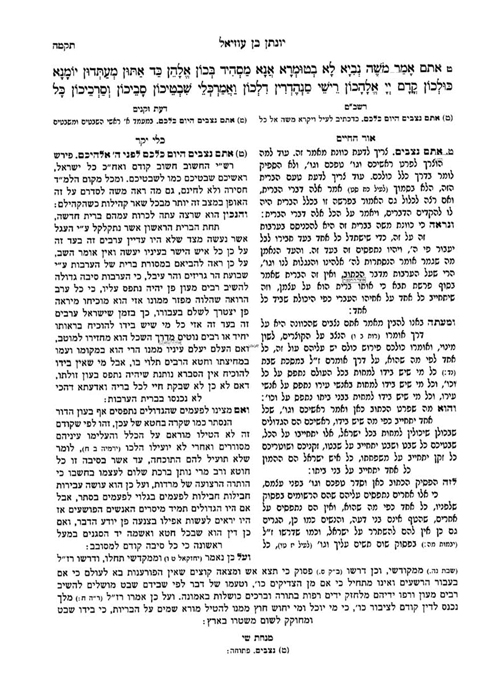

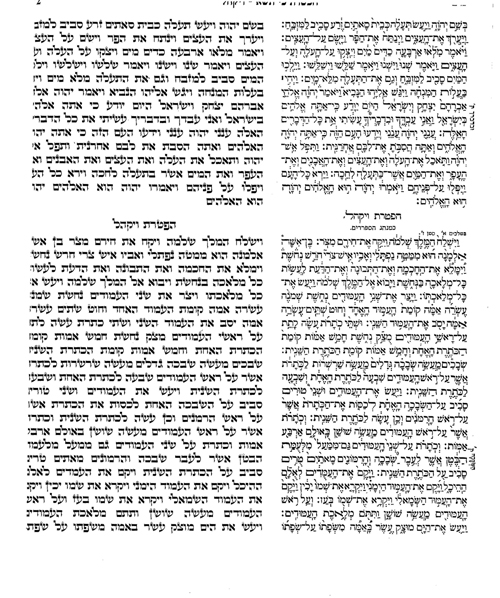

In discussing the prohibition to gash one’s body as idol-worshippers so, Sefer ha-Hinukh states:

אבל שנשחית גופנו ונקלקל עצמנו כשוטים, לא טוב לנו ולא דרך חכמים ואנשי בינה היא, רק מעשה המון הנשים הפחותות וחסרי הדעת שלא הבינו דבר במעשה הא-ל ונפלאותיו.

The Feldheim edition of

Sefer ha-Hinnukh, with Charles Wengrov’s translation, reads as follows:

But that we should be be destructive to our body and injure ourselves like witless fools—this is not good for us, and is not the way of the wise and the people of understanding. It is solely the activity of the mass of low, inferior women lacking in sense, who have understood nothing of God’s handiwork and his wonders.

This is a correct translation. However, Artscroll “translates” the words המון הנשים הפחותות וחסרי הדעת as “masses of small-minded and unintelligent people.” This is clearly a politically correct translation designed to avoid dealing with Sefer ha-Hinukh’s negative comment about the female masses. I will only add that Sefer ha-Hinukh’s statement is indeed troubling. Why did he need to throw in “the women”? His point would have been the exact same leaving this out, as we can see from ArtScroll’s “translation.” Knowing what we know about the “small-minded unintelligent” men in medieval times, it is hard to see why he had to pick on women in this comment, as the masses of ignorant men would have also been a good target for his put-down.

2. In my post

here I wrote:

One final point I would like to make about the Rogochover relates to his view of secular studies. . . . Among the significant points he makes is that, following Maimonides, a father must teach his son “wisdom.” He derives this from Maimonides’ ruling in

Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Rotzeah 5:5:

הבן שהרג את אביו בשגגה, גולה. וכן האב שהרג את בנו בשגגה, גולה על ידו, במה דברים אמורים. כשהרגו שלא בשעת לימוד, או שהיה מלמדו אומנות אחרת שאינו צריך לה. אבל אם ייסר את בנו כדי ללמדו תורה או חכמה או אומנות ומת פטור

He adds, however, that instruction in “secular” subjects is not something that the community should be involved in, with the exception of medicine, astronomy, and the skills which allow one to take proper measurements, since all these matters have halakhic relevance. In other words, according to the Rogochover, while Jewish schools should teach these subjects, no other secular subjects (“wisdom”) should be taught by the schools, but the father should arrange private instruction for his son.

רואים דהרמב”ם ס”ל דגם חכמה מותר וצריך אב ללמוד [!] לבנו אבל ציבור ודאי אסורים בשאר חכמות חוץ מן רפואה ותקפות [!] דשיך [!] לעבובר [צ”ל לעבור] וגמטרא [!] השייך למדידה דזה ג”כ בגדר דין

He then refers to the Mekhilta, parashat Bo (ch. 18), which cites R. Judah ha-Nasi as saying that a father must teach his son ישוב המדינה. The Rogochover does not explain what yishuv ha-medinah means, just as he earlier does not explain what is meant by “wisdom,” but these terms obviously include the secular studies that are necessary to function properly in society.

Dr. Dianna Roberts-Zauderer takes issue with my assumption that “wisdom” (חכמה), the word used by Maimonides, includes what I have termed “secular studies”. (The Touger translation also has “secular knowledge”). She correctly points out that when the medievals used the word חכמה it means philosophy. She adds: “Does it not make sense that Maimonides would advocate the learning of philosophy? Or that the Rogochover would forbid the learning of philosophy in yeshivot, but only permit it at home with a teacher hired by the father?”

Although the term חכמה often means philosophy, I do not think we must assume that this is its meaning in Hilkhot Rotzeah 5:5. Based on parallel passages in Maimonides’ writings where the same halakhah is mentioned, R. Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch claims that the word חכמה in this case actually means good character traits.[1] He sums up his discussion as follows:

כוונת רבינו אחת היא בכל המקומות, דהיינו לימוד מדות הנקרא חכמה

Quite apart from this, in my discussion I was dealing with how the Rogochover understood the passage in Maimonides. We have to remember the context of the Rogochover’s letter. He was asked about the study of secular subjects, as was the practice among the German Orthodox. He was not asked about the study of philosophy per se. Furthermore, in the passage cited from manuscript by R. Judah Aryeh Wohlgemuth,[2] which I referred to in the previous post, the Rogochover specifically understands Maimonides’ term חכמה in Hilkhot Rotzeah 5:5 as meaning שאר החכמות, which he identifies with what R. Judah ha-Nasi calls ישוב המדינה.

Regarding the Rogochover, there are a few things people mentioned to me after seeing my post which I think are worthwhile to record. Dr. Rivka Blau, the daughter of R. Pinchas Teitz, told me that her uncle, R. Elchanan Teitz, would on occasion cut the Rogochover’s hair.

In the post I mentioned how the Rogochover acknowledged that his learning Torah while sitting shiva was a sin, but he did so anyway as the Torah was worth it. R. Yissachar Dov Hoffman called my attention to the following comment about this by R. Ovadiah Yosef, Meor Yisrael, Berakhot 24b:

לפע”ד לא יאומן כי יסופר שת”ח יעבור על הלכה פסוקה בטענה כזו. והעיקר דס”ל כמ”ש הירושלמי פ”ג דמ”ק שאם היה להוט אחר ד”ת מותר לעסוק בתורה בימי אבלו, דהו”ל כדין אסטניס שלא גזרו בו איסור רחיצה מפני צערו.

In the post I mentioned that the Shibolei ha-Leket appears to be the only rishon who adopts the position of the Yerushalmi referred to by R. Ovadiah. R. Yissachar Dov Hoffman called my attention to R. Yehudah Azulai, Simhat Yehudah, vol. 1, Yoreh Deah no. 40, which is a comprehensive responsum on the topic of a mourner studying Torah. R. Azulai notes that a few recently published texts of rishonim record the position of the Yerushalmi. He also mentions that according to some rishonim the prohibition is only to study on the first day of mourning. In studying R. Azulai’s responsum, I found another source that could be used to defend the Rogochover’s learning Torah during shiva. R. Meir ben Shimon ha-Meili writes:[3]

ונראה לומר דלדברי כל פוסקים העיון מבלי הקריאה מותר, שאינו אלא הרהור בעלמא, ולא חמיר אבלות משבת דאמרינן דבור אסור הרהור מותר, וכל שכן הרהור בדברי תורה לאבל שהוא מותר . . . והלכך מותר לו לאבל לעיין בספר, ובלבד שלא יקרא בו בפיו.

R. Meir ben Shimon adds that despite what he wrote, the common practice is for a mourner not to read any Torah books. Yet as we can see, he believes that this is halakhically permitted as long as one does not read out loud.

R. Chaim Rapoport called my attention to the following passage in a new book about the late rav of Kefar Habad, Ha-Rav Mordechai Shmuel Ashkenazi (Kefar Habad, 2017), p. 546:

יצוין בהקשר זה למעשה משעשע, ששח הרב אשכנזי בשם הרה”ח ר’ אליהו חיים אלטהויז הי”ד, אודות אסיפה שכינס הרבי הריי”ץ עם הגיעו לריגה שבלטביה. הרוגצ’ובר נכח באותה ישיבה, ומשנמשכו הנאומים, התקשה הגאון לשבת במנוחה, והוא הסיר את כובעו והשליכו על הבקבוקים שניצבו על השולחן, תוך שערם כוסות שורה על שורה בפירמידה, וכן שפך מים מכוס אחת לשנייה וכדומה.

הרב ד”ר מאיר הילדסיימר [!] ע”ה מברלין, שהיה יקה מובהק, תהה לפשר התופעה והתקשה להכילה. הרבי הריי”ץ חש בפליאתו וציין באוזניו, כי הרוגצ’ובר הינו “שר התורה, וכל רז לא אניס ליה”. השיב הרב הילדסהיימר: “הכול טוב ויפה, אולם נורמאלי זה לא”.

I am surprised that such a passage, using the words “not normal” about behavior of the Rogochover, was published, especially in a Habad work. As is well known, there is a special closeness in Habad to the Rogochover, as he himself was from a Habad family (although it was not Lubavitch but from the Kopust branch of Habad).[4]

Ha-Rav Mordechai Shmuel Ashkenazi also has a number of other stories about the Rogochover. The following appears on p. 211: Once R. Jacob David Wilovsky of Slutzk visited R. Meir Simhah of Dvinsk and told him that he wanted to also visit the Rogochover. R. Meir Simhah attempted to dissuade him, saying that the Rogochover would put him down like he puts everyone down. Yet R. Wilovsky visited him and the Rogochover did not put him down. He said to the Rogochover, “I heard that you put down everyone, but I see that you treat me with respect.” The Rogochover replied, “I put down gedolim, not ketanim.”

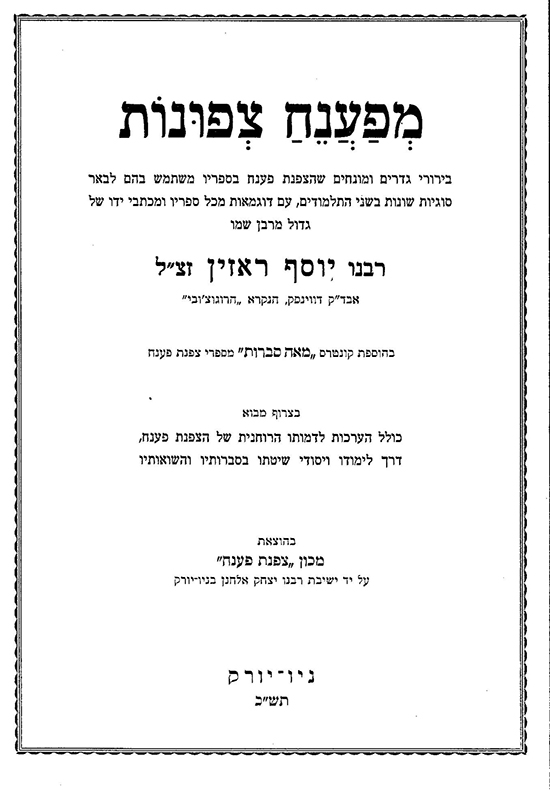

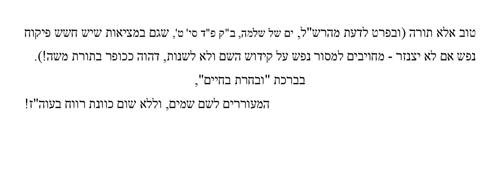

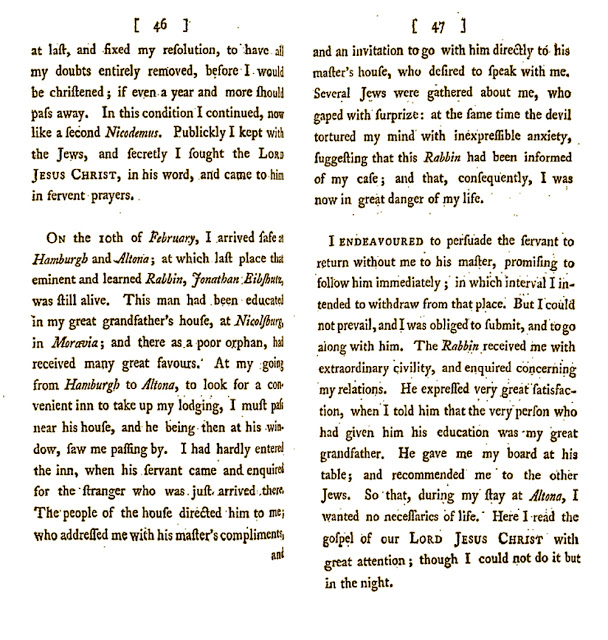

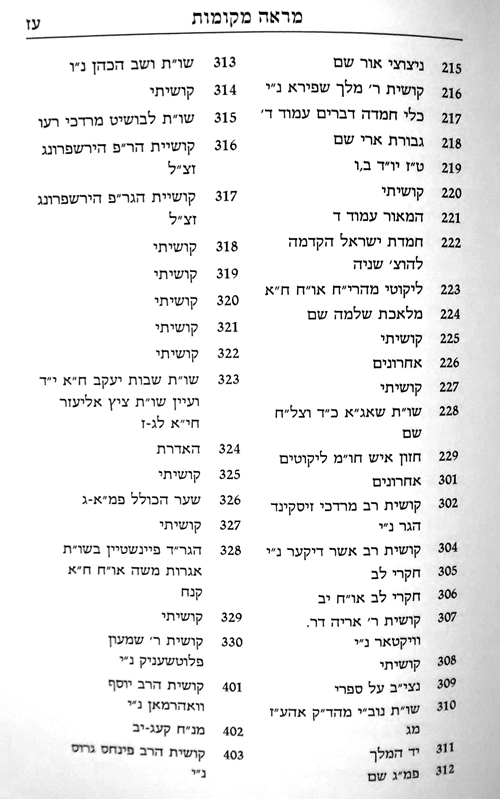

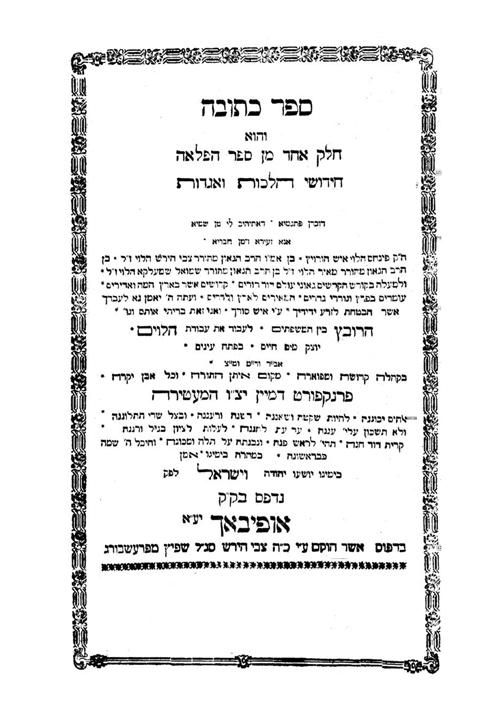

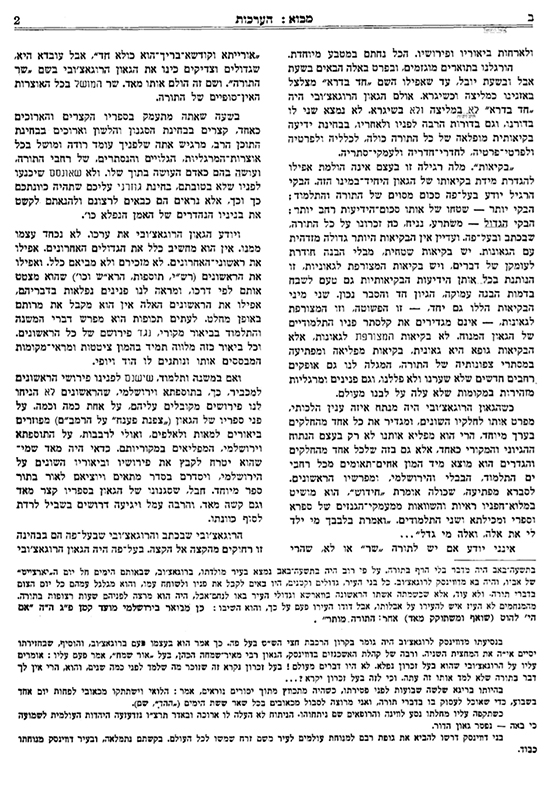

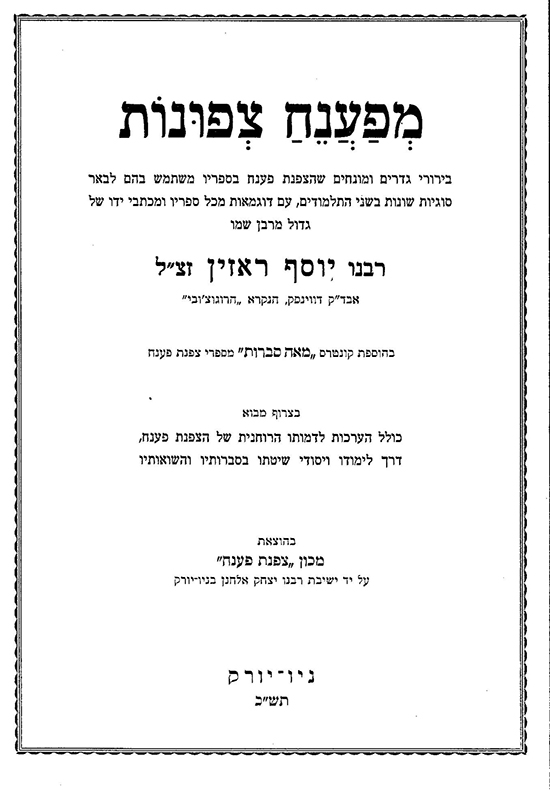

In my post on the Rogochover, I showed this page from R. Menahem Kasher’s

Mefaneah Tzefunot (Jerusalem, 1976), p. 2.

I wrote:

Look at the end of the first paragraph of the note on p. 2. The “problematic” quotation of the Rogochover, saying that he will happily be punished for his sin in studying Torah, as the Torah is worth it, has been deleted. Instead, the Rogochover is portrayed as explaining his behavior as due to the passage in the Yerushalmi. While all the other authors who discuss this matter and want to “defend” the Rogochover claim that his real reason for studying Torah was based on the Yerushalmi, in R. Kasher’s work this defense is not needed as now we have the Rogochover himself giving this explanation!

Yet the Rogochover never said this. R. Zevin’s text has been altered and a spurious comment put in the mouth of the Rogochover. By looking carefully at the text you can see that originally R. Zevin was quoted correctly. Notice how there is a space between the first and second paragraphs and how the false addition is a different size than the rest of the words. What appears to have happened is that the original continuation of the paragraph was whited out and the fraudulent words were substituted in its place. Yet this was done after everything was typeset so the evidence of the altering remains.

I had forgotten that the 1976 edition of

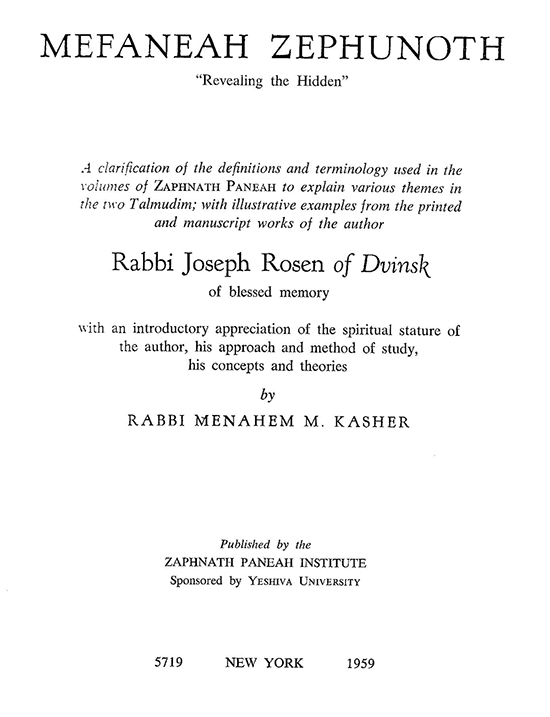

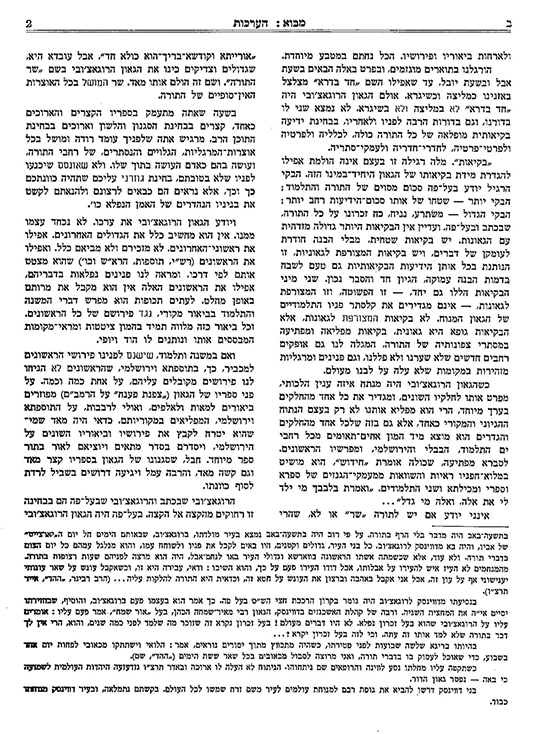

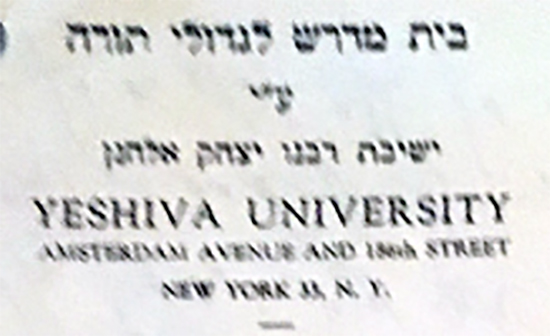

Mefaneah Tzefunot, which is the one found on Otzar ha-Hokhmah and hebrewbooks.org, was the second publication of the book. I thank David Scharf for reminding me of this and for sending me copies of the following pages. Here are the Hebrew and English title pages of the first edition.

Notice how the two title pages have different publication dates. At that time, Yeshiva University was helping to fund R. Kasher’s work on the Rogochover.[5]

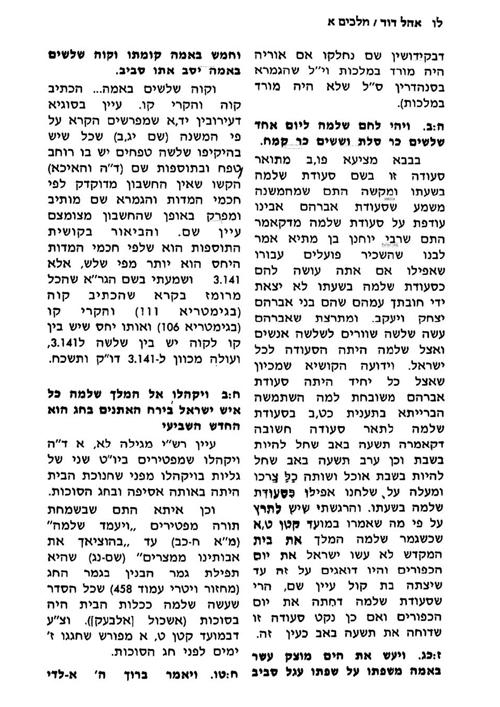

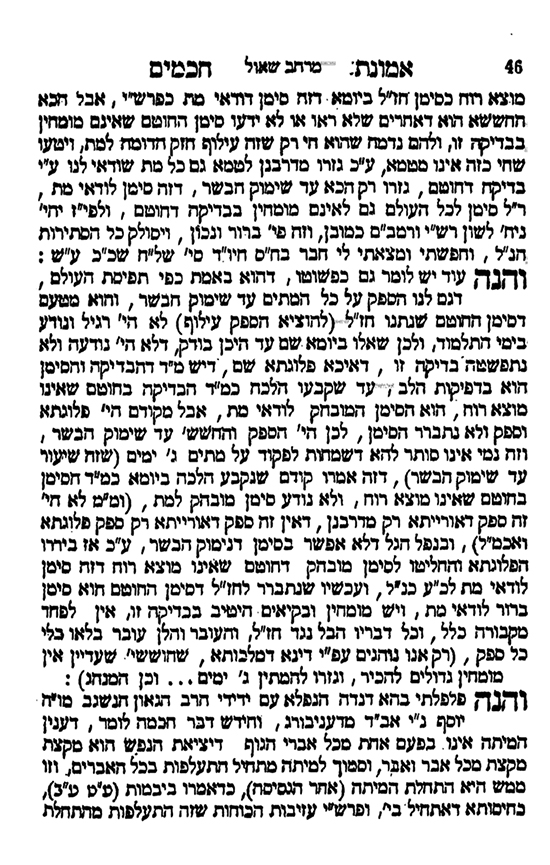

Here is page 2 of the preface.

As you can see, in the original publication the text from R. Zevin appears in its entirety. It is only in the second edition that R. Kasher altered what R. Zevin wrote.

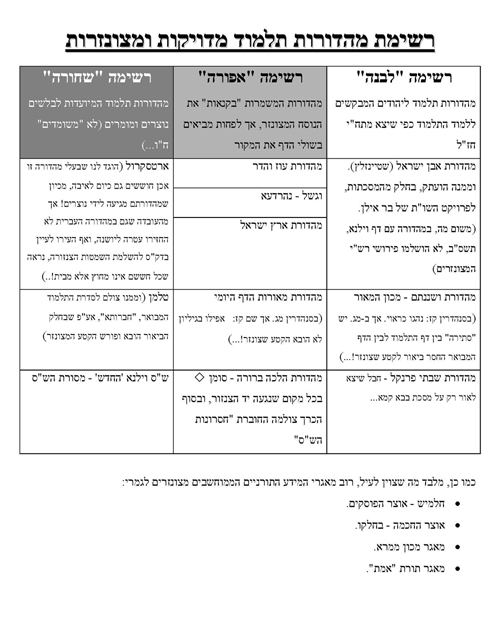

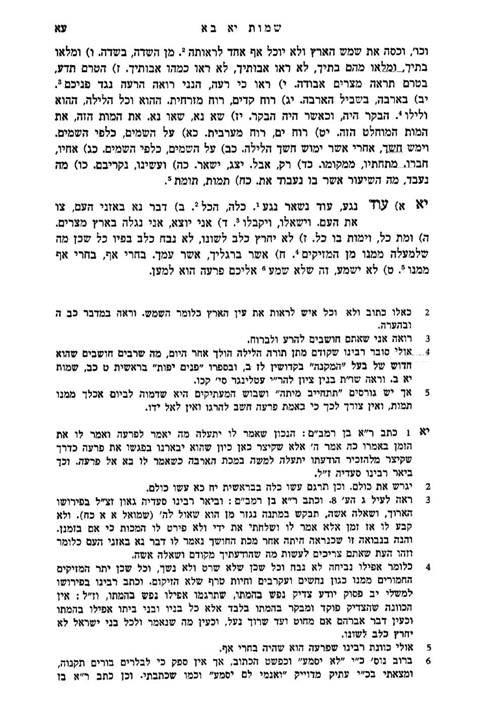

There is a good deal more to say about the Rogochover, so let me add another point. In 1892 R. Dov Baer Judah Leib Ginzberg published his

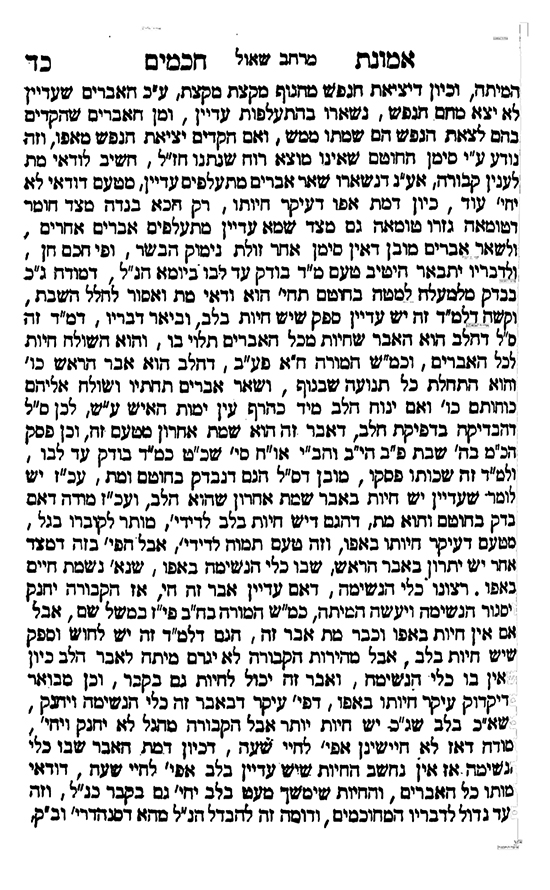

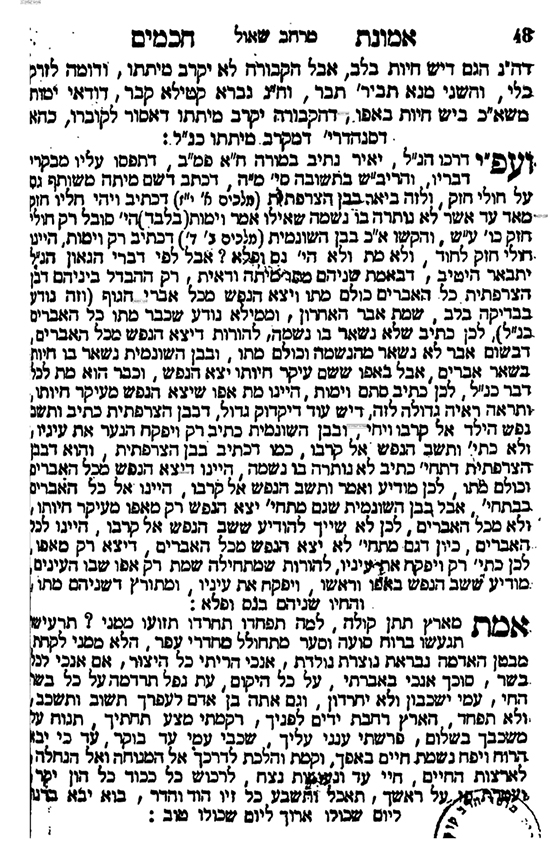

Emunat Hakhamim. Included in it, on pages 23b-24b, is a report of how the Rogochover understood the time of death. I believe that what he states can be used to support the argument that brain death is equal to halakhic death. Here are the pages.

The matter of antinomianism, and in particular the Rogochover violating halakhah in the name of a higher purpose, is of interest to many people. In a future post I will cite an example concerning which I think everyone (or most everyone) will agree that even though the halakhah is clear, nevertheless, even the most pious will not hesitate to violate the halakhah in this particular case, again, because of a larger concern.

For now, I want to call attention to another who, like the Rogochover, was very unusual. R. Shlomo Aviner writes as follows:[6]

בישיבת “מרכז הרב” היה גאון אחד בשם הרדיצ’קובר, שהיה מתנהג בצורה משונה. הוא היה נכנס לשירותים עם ספר הרמב”ם. אמרו לו: אסור! ותשובותו: “הרי גם הרמב”ם עצמו היה נכנס לשרותים!”כשנפטר, היו האנשים נבוכים בהספד שלו, שהרי היה תלמיד חכם, אך התנהג בצורה מוזרה מאד. הרב נתן רענן, חתנו של מרן הרב, הספיד אותו ואמר, שגדולתו היתה אהבת התורה, ומרוב אהבת התורה עשה דברים שלא יעשו. הוא חטא חטאים שנבעו מאהבת התורה.

R. Aviner speaks about a gaon known as the Radichkover who was quite strange. He would go into the restroom holding a copy of the Mishneh Torah. When he was told that this is forbidden, he replied that Maimonides himself went to the restroom! In other words, if Maimonides could go into the restroom then certainly his book can be brought into it. The Radichkover actually tells this story himself about bringing R. Reuven Katz’s book, Degel Reuven, into the restroom.[7]

When he died, people did not know how to eulogize him, because on the one hand he was a great talmid hakham, but on the other hand he acted in a very strange manner. R. Aviner tells us that R. Natan Ra’anan, the son-in-law of R. Kook, delivered the eulogy and said that his greatness was his love of Torah, and due to this great love he did things that were improper. “He sinned yet these sins arose from his love of Torah.”

It is obviously not very common that a eulogy mentions improper things done by the deceased. It is also understandable why, due to his unconventionality, the Radichkover reminds people of the Rogochover. For those who have never heard of him, his name was R. Yaakov Robinson (1889-1966), and before coming to Eretz Yisrael he studied with R. Baruch Ber Leibowitz. You can read more about him

here and

here. Two responsa in R. Moshe Feinstein’s

Iggerot Moshe were sent to the Radichkover. Both of these responsa are from 1933, when R. Moshe was still in Russia.[8]

If you look at the Wikishiva page on the Radichkover

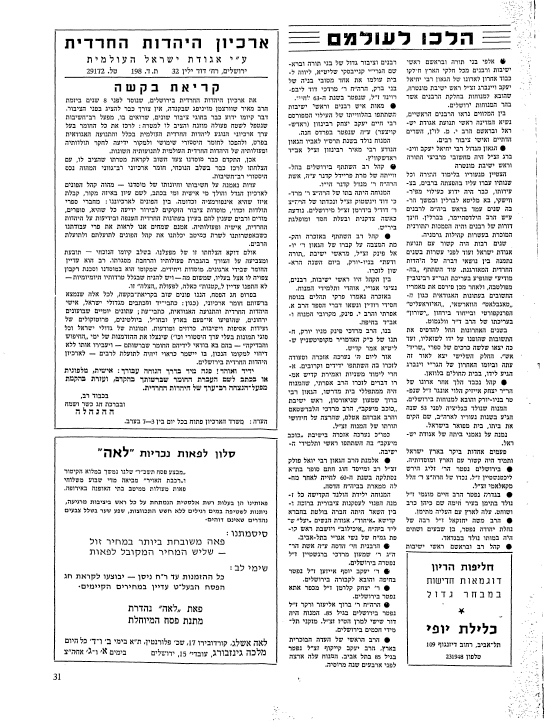

here, it says that he died in 1977. So how do I know that this is incorrect and that he died in 1966? Because he died at the same time as R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg. Here is a page from

Beit Yaakov, Shevat 5726, p. 31, and you can see the announcement of both of their funerals.

It is typical of an Agudah publication like Beit Yaakov that it would falsely state that R. Weinberg was connected for many years with Agudat Israel. This is as false as the newspaper’s statement that he served as rosh yeshiva in Montreux.

A number of sharp comments of the Radichkover became well known in the Jerusalem yeshiva world and are mentioned in the two sites I linked to above. See also

here for more of his sayings. Here is one I liked, which was written by the Radichkover in one of his works (mentioned

here).[9]

הבוקר אחרי התפילה ניגש אלי יהודי ושאל אותי למה אני יושב ב”ויברך דוד”. חשבתי לעצמי, זה שאני יושב בלי אשה, זה לא מפריע לו, זה שאני יושב בלי פרנסה, זה לא מפריע לו, מה כן מפריע לו, שאני יושב בויברך דוד . . .

Here is another great story dealing with the Hazon Ish (mentioned

here)

ר’ יענקל היה נתון תדיר בתחושת רדיפה. מעולם לא אכל אוכל שלא הכין בעצמו ועוד שאר דברים ע”ז הדרך. פעם נזעק לביתו של החזון אי”ש בטענה כי אחדים מבני הישיבה ניסו להרעילו. מה עליו לעשות. שאלו החזון אי”ש: “מה שמו בכוס קודם – את התה או את הסם”. הרהר ר’ יענקל קלות וענה: “קודם את התה ואח”כ את הסם”. נענה החזו”א: “אנחנו הרי פוסקים שתתאה גבר”. ונח דעתיה.

In the recently published conversations of the late R. Meir Soloveitchik,

Da-Haziteih le-Rabbi Meir, vol. 1, p. 159, the Hazon Ish’s wife is quoted as saying as follows about the Radichkover:

מה”שברי לוחות”, אפשר לראות ולשער מה היו הלוחות השלמות, כאשר היה בריא

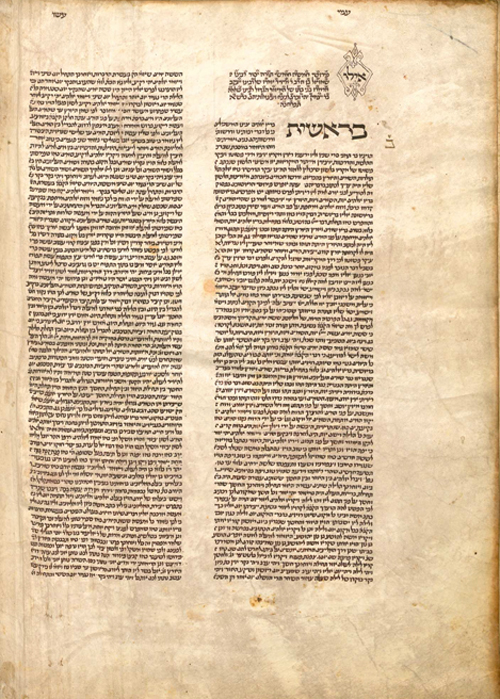

While the Radichkover never published any full-length books, he published a number of short pieces. Here is the first page of his Masa Dumah.

Here is the first page of his Olam Gadol Oleh ve-Olam Katan Shokea.

A short glance at either of these works should suffice to show that we are not dealing with a “normal” talmid hakham. In Olam Gadol, p. 10, he reports that the Rogochover said about him that he was the greatest Torah scholar alive! Here is page 15 of Olam Gadol. It hardly needs to be said that what he includes here about the locked rest rooms is not the typical material found in seforim.

In Masa Dumah, p. 8, he makes the following sharp comment about R. Joseph Kahaneman. “They asked me in the Ponovezh yeshiva, what I have to say about the Ponovezher Rav. I said to them that he is greater than the Maharal of Prague. The Maharal created one golem and he created three hundred golems. The Ponovezh Yeshiva is a factory for am ha’aratzut.”

Excursus

The people who saw the Radichkover sitting during Vayvarekh David were bothered since everyone knows that this is recited standing. The ArtScroll siddur states: “One must stand from ויברך דויד until after the phrase אתה הוא ה’ הא-להים, however there is a generally accepted custom to remain standing until after ברכו.” I don’t like this formulation. On what basis can ArtScroll state that “one must stand”? The word “must” means that we are dealing with a halakhah, i.e., an obligation. But that is not the case at all. Standing in Vayvarekh David is only a minhag, like much else we do in the prayers.[10] As such, I think it would have been proper for ArtScroll to write, “The generally accepted practice is to stand from ויברך דויד” etc.

R. Moses Isserles, Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 51:7, refers to standing in Vayvarekh David, and his language is as follows:[11]

ונהגו לעמוד כשאומרים ברוך שאמר ויברך דוד וישתבח

On this passage, the Vilna Gaon writes: לחומרא בעלמא, “it is only a stringency”. R. Jehiel Michel Epstein, Arukh ha-Shulhan, Orah Hayyim 51:8, also writes that there is no halakhah to stand for Vayvarekh David.

ומצד הדין אין שום קפידא לבד בשמ”ע ומחויבים לעמוד וקדושה וקדיש וברכו.

R. Epstein returns to this matter in Arukh ha-Shulhan, Yoreh Deah 214:23. This passage is not well known as this volume of Arukh ha-Shulhan was only printed in 1991 and is not included in the standard sets of Arukh ha-Shulhan that people buy. R. Epstein writes:

מדינא דגמ’ מותר לישב בכל התפלה לבד שמונה עשרה דצריך בעמידה ושיש הרבה נוהגים ע”פ מה שנדפס בסידורים לעמוד כמו בויברך דוד וישתבח ושירת הים וכיוצא בהם גם זה אינו מנהג לקרא למי שאינו עושה כן משנה ממנהג וראיה שהרי יש מן הגדולים שחולקים בזה.

According to R. Epstein, one does not even violate a minhag by sitting for Vayvarekh David and the rest of the prayers through Yishtabah.

So we see that when it comes to standing, Vayvvarekh David has the same status as Yishtabah, i.e., standing for both is minhag. Yet ArtScroll mistakenly separates the two, regarding the standing for Vayvarekh David as halakhah and the standing for Yishtabah (and everything in between) as “a generally accepted custom.” It is worth noting that the Mishnah Berurah, Orah Hayyim 51:19, only mentions the custom of standing in Vayvarekh David, not the current practice of standing until after Yishtabah. I must note, however, that the Kaf ha-Hayyim, Orah Hayyim 51:43, quotes R. Isaac Luria that one has to stand, צריך לעמוד, during Vayevarekh David. This is similar to ArtScroll’s formulation, but I find it hard to believe that ArtScroll’s instructions are based on kabbalistic ideas.

R. Jacob Moelin (the Maharil) did not stand for Vayvarekh David. See Sefer Maharil, Makhon Yerushalayim ed., Hilkhot Tefilah, no. 1, p. 435, and R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach, Mekor Hayyim 51:7. See also R. Jacob Sasportas, Ohel Yaakov, no. 74, for a report that in Hamburg they did not stand for Vayvarekh David.

R. Samuel Garmizon (seventeenth century), Mishpetei Tzedek, no. 70, was asked about someone who was accustomed to stand in Vayvarekh David (and also in Barukh She-Amar) but now wishes to sit. Is he allowed to? R. Garmizon states that if he mistakenly thought that it was an obligation to stand and has now learned that it is only a pious practice (minhag hasidim), then he is permitted to sit and it is not regarded as if he took on a stringency as an obligation. The Yemenite practice is also not to stand for Vayvarekh David. See R. Yihye Salih, Piskei Maharitz, ed. Ratsaby, vol. 1, p. 118.

While readers might find this all interesting, they might also be wondering what it has to do with the Radichkover, since hasn’t Ashkenazic practice in the last few generations been universally to stand? Actually, this has not been the case. R. Israel Zev Gustman stated that in the Lithuanian yeshivot the practice was to sit for Vayvarekh David, and also for Yishtabah. They only stood for Barukh She-Amar and the kaddish after Yishtabah. See Halikhot Yisrael, ed. Taplin (Lakewood, 2004), p. 117.

R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach said that the general practice is to sit for Vayvarekh David. See R. Nahum Stepansky, Ve-Alehu Lo Yibol, vol. 1, p. 61:

יש הרבה דברים שכתוב שנהגו לעמוד בהם, ואנחנו רואים שנוהגים שלא לעמוד בהם. ב”ויברך דוד” כותב הרמ”א שנהגו לעמוד – ולא עומדים.

I find this astounding. I have been to Ashkenazic synagogues all over the word and I have never seen people sit for Vayvarekh David. Yet R. Shlomo Zalman says that this is what people do. This passage comes from a discussion of how R. Shlomo Zalman dealt with a young yeshiva student who pressed him that people in the synagogue should stand when someone gets an aliyah and recites Barkhu. R. Shlomo Zalman replied that the minhag is to sit, adding, “You don’t see what people do?!” In other words, the fact that people sit when someone gets an aliyah shows us that this is the minhag and it should not be changed, despite what might appear in various halakhic texts.

Regarding standing during prayers, I have noticed something else. When I was young many of the old timers would sit for the various kaddishes. Today, in the Ashkenazic world, it seems that everyone stands for every kaddish, and this is in line with what R. Moses Isserles writes in

Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 56:1. Also, it seems that for the communal

mi-sheberakh for sick people everyone also stands, and in some shuls they announce that everyone should stand. Why is this done? I cannot think of any reason to stand for this

mi-sheberakh unless it is a way to get people to stop talking.

Michael Feldstein recently commented to me that in the last ten years or so he has seen something that did not exist in earlier years, namely, people standing for Parashat Zakhor. I, too, noticed this in my shul, but it has only been going on for a year or two. This year, no one announced that people should stand. Some just stood up on their own and pretty much the entire shul then joined in. Unless the rabbis start announcing that people can sit down, in a few years it will probably become obligatory to stand for Parashat Zakhor, much like it now seems to be obligatory to repeat the entire verse, whereas when I was young the only words to be repeated were תמחה את זכר עמלך. (I always paid attention to this as Ki Tetze is my bar mitzva parashah.) Today, if the Torah reader tries to repeat only these words, they will tell him to go back and repeat the entire verse. What we see from all of this is that customs are constantly being created, and they often arise from the “ritual instinct” of the people, without any rabbinic guidance.

Two final points: 1. In the word ויברך the yud is a sheva nah (silent shewa). 2. The accent is on the second to last (penultimate) syllable, the ב, not on the final syllable, the ר. This word also appears in Friday night kiddush, and it is very common to hear people, including rabbis, make the mistake of treating the yud as a sheva na (vocal shewa) and also putting the accent on the last syllable. Many people also make a mistake at the beginning of kiddush by pronouncing the word ויכלו with the accent on the second to last syllable, the כ, when it should be on the last syllable, the ל. Another common pronunciation mistake is found in the Shabbat morning kiddush. וינח has the accent on the second to last syllable, the י, not on the final syllable, the נ.

Regarding the instructions in the ArtScroll siddur, another example of confusion is found in the commentary on Av Ha-Rahamim, pp. 454-455. ArtScroll writes:

As a general rule, the memorial prayer [Av ha-Rahamim] is omitted on occasions when Tachanun would not be said on weekdays, but there are any numbers of varying customs in this matter and each congregation should follow its own practice. During Sefirah, however, all agree that אב הרחמים is recited even on Sabbaths when it would ordinarily be omitted, because many bloody massacres took place during that period at the time of the Crusades. Here, too, there are varying customs, and each congregation should follow its own.

In the second-to-last sentence, ArtScroll says that “all agree”, but in the very next sentence it states that “there are varying customs.” If there are varying customs, then obviously not “all agree”. Incidentally, R. Zvi Yehudah Kook said Av ha-Rahamim every Shabbat, i.e., even when the accepted minhag is to omit it, since he felt that after the Holocaust this was the appropriate thing to do. See Va-Ani be-Golat Sibir (Jerusalem, 1992), p. 298.

Finally, since I have been speaking about different customs in prayer, I should mention something that I forgot to include in my post

here, dealing with China. I believe that, outside of Israel, there is only one Ashkenazic synagogue in the world that has

birkat kohanim every day.[12] This is Ohel Leah in Hong Kong. (R. Mordechai Grunberg, who has traveled all over the world as an OU mashgiach and currently works in China, told me that as far as he knows this statement is correct. I had the pleasure to spend Shabbat with him and three mashgichim from the Star-K at the wonderful Chabad House in Shanghai in June 2018.)

I have no doubt that the reason for the Ohel Leah minhag is because its nineteenth-century community was Sephardic. At some time in the twentieth century (no one was able to tell me when) the liturgy became Ashkenazic, but the daily birkat kohanim was kept. Interestingly, although the liturgy is Ashkenazic, it is nusah sefard. I assume the reason for this is that when they decided to adopt the Ashkenazic liturgy they wanted it to still have a Sephardic flavor, and that is why they chose nusah sefard.

* * * * * * *

2. Simcha Goldstein called my attention to how earlier this year the 5 Towns Jewish Times “touched up” a picture of Ivanka Trump.

3. Here is a painting of the Rav, R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik. It was commissioned by his wife when he was fifty years old. The Rav later gave this painting to Rabbi Julius Berman, and it is currently hanging in his home. I thank Rabbi Berman who graciously allowed me to publish a picture of the painting.

4. Tzvi H. Adams contributed three fascinating and thought-provoking posts to the Seforim Blog dealing with the impact of Karaism on rabbinic literature. He has now published a comprehensive article on this matter in

Oqimta, available

here. Its title is “The Development of a Waiting Period Between Meat and Dairy: 9th-14th Centuries.” There is a good deal to say about this article, but let me just make a couple of comments. On p. 4 he writes:

Even many minhagim extant today were arguably initiated as a response to the Karaite movement. For example, many historians agree that the recital of the 3rd chapter from Mishnat Shabbat, “Bamme Madlikin,” on Friday evenings following the prayer service was introduced during the time of the geonim with the intent of reinforcing the rabbinic stance on having fire prepared before Shabbat, in opposition to the Karaite view that no fire may be present in one’s home on Shabbat.[13] Similar arguments have been made for the origins of the custom of reading Pirkei Avot, the introduction of which traces rabbinic teachings to Sinai, on Shabbat afternoons. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that the creation of Ta’anit Esther in geonic times was likely a reaction to Karaite practices.

Later in the article, p. 57 n. 141, Adams mentions what might be the most prominent example of a response to Karaite practices, namely, reciting a blessing on the Shabbat candle. This blessing does not appear in the Talmud.[14] It is a geonic innovation, and according to R. Kafih it was instituted in opposition to the Karaite view that no fire should be burning in one’s home on the Sabbath.[15] He argues that by adding a blessing to the candle lighting, the geonim created an anti-Karaite ritual. While the Karaites would sit in the dark every Friday night, not only would the Jews have light, but they would recite a blessing before lighting the candle,[16] thus showing their rejection of the Karaite position.[17] R. Meir Mazuz makes the exact same point,[18] as does R. Abraham Eliezer Hirschowitz,[19] Isaac Hirsch Weiss,[20] Jacob Z. Lauterbach,[21] and Naphtali Wieder.[22]

In fact, some have argued that not only the blessing but the candle lighting itself was instituted in response to heretics who did not use fire on the Sabbath. As Lauterbach states, “It was as a protest against the Samaritans and the Sadducees.”[23] R. Kafih sees R. Joseph Karo as sharing this opinion. He writes as follows, quoting Maggid Meisharim (and assuming that what the Maggid says represents R. Karo’s view).[24]

וכתב מרן בספרו מגיד מישרים ר”פ ויקהל ואמר ביום השבת, למימר דדוקא ביום השבת גופיה הוא דאסור לאדלקא, אבל מבעוד יום לאדלקה ליה ויהא מדליק ומבעיר ביומא דשבתא שרי. ולאפוקי מקראים דלית להו בוצינא דדליק ביומא דשבתא ע”ש. נראה שגם מרן ראה בחובת הדלקת נר בשבת גם פעולה נגד דעות הכופרים בתורה שבע”פ שעליהם נאמר ורשעים בחשך ידמו.

Regarding the Shabbat candle, it is also worth noting that R. Judah Leib Landsberg actually stated that the practice of candle lighting was adopted from the Persians. Since the Jews were so attached to what was a pagan practice, Ezra and Nehemiah directed this practice towards a holy purpose, much like the origin of sacrifices was explained by Maimonides.[25]

ואפילו היה דומה למנהגי הפרסיים, לא היה ביד עזרא ונחמיה הכח והרצון לעקור המנהג הנשתרש באומה משנים קדמוניות, ולכבה האש זר “החברים” מבית ישראל. ובכל זאת למען תת לו איזה חינוך קדושה קדשוהו ותקנוהו להדליק האש של חול לנר קודש לקדושת השבת, כסברת הרמב”ם ז”ל בענין קרבנות כנודע.

He later acknowledged that this was not a serious explanation and claimed that the practice of candle lighting went back to Moses.[26]

One final comment about Karaites: Rashi,

Sukkah 35b, s.v. הרי יש, has a strange formulation. In discussing the prohibition to redeem terumah so that an Israelite could eat it, Rashi writes:

הרי יש בה היתר אכילה לכהן, וישראל נמי נפיק בה, או לקחה מכהן הואיל ויכול להאכילה לבן בתו כהן, אבל פדיון אין לה להיות ניתרת לאכילת ישראל, והאומר כן רשע הוא

How is it that Rashi refers to one who makes a mistake in this matter as a רשע? Many people have attempted to explain this passage. R. Isaac Zev Soloveitchik noted that there must have been a sect that believed that it was permitted to redeem terumah, and that is why Rashi responded so sharply.[27] Regarding this suggestion of R. Soloveitchik we can say, חכם עדיף מנביא.

R. Tuvya Preschel’s Ma’amrei Tuvyah, volume 3, recently appeared. On p. 67 it reprints an article that appeared in Sinai in 1966. Preschel points out that the notion that terumah can be redeemed is stated by none other than Anan ben David in his Sefer ha-Mitzvot. It appears that Rashi knew of this Karaite opinion and this explains his harsh reaction. This was a great insight by Preschel, Unfortunately, while this insight has been cited by many in the last fifty years, Preschel is almost never given credit.

5. Many countries in Europe have Stolpersteins. These are brass plates, created by the artist Gunter Demnig, commemorating martyrs of the Holocaust. They are put in the pavement in front of buildings where the martyrs lived. A few years ago Demnig also started doing this for survivors of the Holocaust. I arranged to have one made for R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg.

After almost two years of waiting, I am happy to report that on June 18, 2018, a Stolperstein was placed at Wilmersdorfer Strasse 106, in Berlin. There was a little ceremony when the Stolperstein was inserted. Here is a picture of Demnig installing it as well as some other pictures that I think people will find moving.

[1] Yad Peshutah, Hilkhot Rotzeah 5:5.

[2] Yesodot Hinukh ha-Dat le-Dor (Riga, 1937), p. 250.

[3] Sefer ha-Meorot, Moed Katan, ed. Blau (New York, 1964), pp. 73-74 (to Moed Katan 20a).

[4] For a great story about the Rogochover told by R. Menahem Mendel Schneerson, see

Likutei Sihot, vol. 16, pp. 374-375.

[5] Yeshiva University’s Gottesman Library also has a large archive of over 2500 letters and postcards sent to the Rogochover. This material was sent to the United States before World War II by the Rogochover’s daughter. I published a lengthy letter from this collection in my article on the dispute over the Frankfurt rabbinate. See Milin Havivin 3 (2007), pp 26-33.

The Zaphnath Paneah Institute at YU no longer exists. When I look at old material from YU, I often come across things that are now only a memory. Here is something I think people might find interesting.

(Unfortunately, the picture I took is not so clear.) The Beit Midrash li-Gedolei Torah was the name of a kollel at YU in the 1940s and 1950s headed by R. Avigdor Cyperstein. I thank his daughter, Mrs. Naomi Gordon, for allowing me to go through his papers where I found the stationery with the name of the kollel. R. Gedaliah Dov Schwartz was actually a member of this kollel. See Ha-Pardes, Tevet 5751, p. 58 and Kislev 5752, p. 1. Today YU has a number of kollels, see here, but none with this name. Does anyone know when this kollel stopped functioning?

[6] Mi-Shibud li-Geulah mi-Pesah ad Shavuot (n.p., 1996), p. 87.

[7] See his Masa Dumah, p. 4.

[8]

Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Deah, vol. 1, nos. 4, 74. The first responsum mistakenly has the place of authorship as London, when it should say Luban. The city name appears correctly in the second responsum, which was written on the same day as the first. See

here.

[9] See the Excursus where I discuss standing for Vayvarekh David.

[10] Saying Vayvarekh David is itself only a minhag. See Tur, Orah Hayyim 51:7:

ובתקון הגאונים כתוב יש נוהגים לומר ויברך דוד את ה’

[11] In Darkhei Moshe, Orah Hayyim 51 he writes:

המנהג עכשיו לעמוד מויברך דוד עד תפראתך

From his words we see that people only stood for the first half of Vayvarekh David.

[12] There is a lot of confusion as to how to pronounce the word ברכה in both the singular and plural construct: ברכת and ברכות. The first is pronounced birkat, as there is a dagesh in the כ. The second is pronounced birkhot, as there is no dagesh in the כ, and is parallel to the word הלכות – hilkhot. Interestingly, ברכתי (“my blessing”) does not have a dagesh in the כ even though ברכת does. I don’t think that there is any grammatical rule that can adequately explain all this. We know how the words related to ברכה are pronounced because they are attested to numerous times in Tanakh.

The word הלכות does not appear in Tanakh, and the Yemenite tradition is actually to pronounce it as

hilkot, with a

dagesh in the כ. See

here. When not quoting from Tanakh, the Yemenite tradition is also to pronounce ברכת as

birkhat, as in

birkhat ha-mazon. See

here.

[13] It is not only historians who say this. See R. Yitzhak Yeshaya Weiss, Birkat Elisha (Bnei Brak, 2016), vol. 3, p. 37, and see also R. Shimon Szimonowitz, Meor Eifatekha, p. 4, who cites R. Jacob Schorr and R. Serayah Deblitsky.

[14] A number of Ashkenazic rishonim quote a passage from the Jerusalem Talmud that speaks of a blessing on the Sabbath light, yet this is not found in any extant text and scholars agree that it is not an authentic Yerushalmi text. See the comprehensive discussion in R. Ratzon Arusi, “Birkat Hadlakat Ner shel Yom Tov,” Sinai 85 (1979), pp. 63ff. See also Jacob Z. Lauterbach, Rabbinic Essays (Cincinatti, 1951), p. 459 n. 98 and Sefer Ra’avyah, ed. Aptowitzer, vol. 1, p. 263 n. 10.

[15] See Teshuvot ha-Rav Kafih le-Talmido Tamir Ratzon, ed. Itamar Cohen (Kiryat Ono, 2016), pp. 162-163, and R. Kafih’s commentary to Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Shabbat 5:1, n. 1.

[16] I use the word “candle”, rather than the plural, “candles”, as the practice of lighting two candles only originated later, in medieval Ashkenaz. See R. Gedaliah Oberlander, Minhag Avoteinu Be-Yadenu: Shabbat Kodesh (Monsey, 2010), pp. 11ff. I was surprised to learn that R. Meir Soloveitchik’s daughters each lit a Shabbat candle and recited the blessing from the time they were three years old. See Da-Haziteih le-Rabbi Meir, vol. 1, p. 323.

[17] In later years we find that some Karaites adopted the practice of lighting candles on Friday night. Se Dov Lipetz, “Ha-Karaim be-Lita,” in Yahadut Lita (Tel Aviv, 1959), vol. 1, p. 142

[18] Bayit Ne’eman 38 (25 Heshvan 5777), p. 3, Bayit Ne’eman 118 (10 Tamuz 5778), p. 2 n. 9. In She’elot u-Teshuvot Bayit Ne’eman, p. 190, he does not present this approach as absolute fact, but states that it is “nearly certain”.

וקרוב לודאי שברכת נר שבת נתקנה בימי הגאונים להוציא מדעת הקראים

[19] Otzar Kol Minhagei Yeshurun (St. Louis, 1917), p. 232.

[20] Dor Dor ve-Doreshav (Vilna, 1904), vol. 4, p. 97. Weiss points to other examples of practices that he suggests were a response to Karaites, such as counting the omer at night, betrothing a woman with a ring, and reciting רבי ישמעאל אומר in the morning prayers. R. Judah Leib Maimon claims that the practice of a Saturday night melaveh malka was instituted by the geonim in opposition to the Karaites, who saw the Sabbath as a difficult and depressing day, in contrast to traditional Jews who find it difficult to part with the Sabbath. See Sefer ha-Gra, ed. Maimon (Jerusalem, 1954), vol. 1, p. 80.

[21] Rabbinic Essays, p. 460. He writes that the blessing was “probably intended as a more emphatic protest against the Karaites.”

[22] “Berakhah Bilti Yeduah al Keriat Perek ‘Bameh Madlikin,’” Sinai 82 (1978), p. 217.

[23] Rabbinic Essays, p. 459. See also Yehudah Muriel, Iyunim ba-Mikra (Tel Aviv, 1960), vol. 2, p. 131.

[24] Commentary to Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Shabbat 5:1, n. 1.

[25] Hikrei Lev (Satmar, 1908), vol. 4, p. 84.

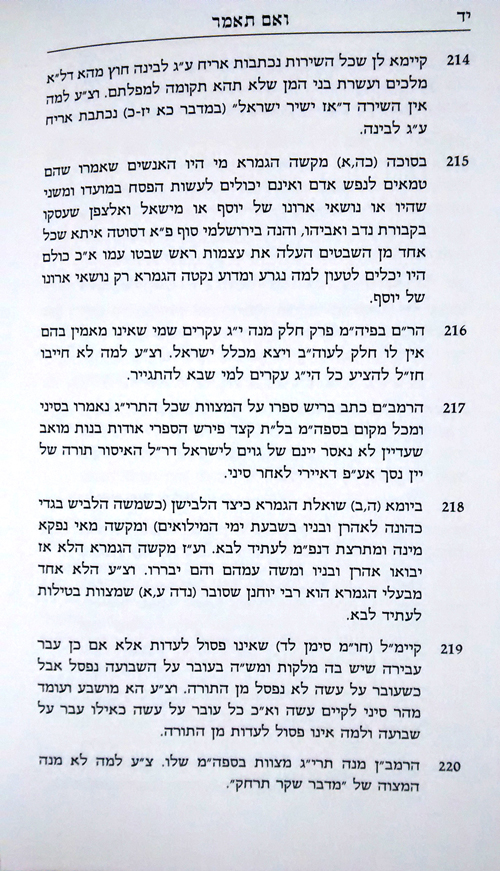

[27] Shimon Yosef Meler, Uvdot ve-Hanhagot mi-Beit Brisk (Jerusalem, 2000), vol. 4, p. 310.