The Longest Masechta is …

The Longest Masechta is …

By Ari Z. Zivotofsky

As Jews, we are often intrigued with trivia about our holy books, and the more esoteric and harder to verify, the better. An example of such trivia is the longest masechta in shas. While it is relatively easy to verify that the longest masechta in terms of pages in the Vilna Shas is Bava Batra, with 176 pages,[1] until modern times it was much more difficult to determine which is the largest masechta in terms of words or characters. Once something is difficult to measure, rumors abound, and this topic is no different. To cite just three examples. Meorot haDaf Yomi on 23 Shvat 5770 (vol. 559), stated (in Hebrew) that if not for the lengthy commentary of Rashbam, Bava Batra would have considerably fewer pages and that the Gra had said that really the longest masechta in terms of words is Berachot, although it is only 64 pages. Rabbi Yaakov Klass in the Jewish Press (20 Tammuz 5777 / July 13, 2017) wrote: “as the Vilna Gaon observes, Berachos is actually the longest tractate”. Rabbi Aaron Perry in his “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to the Talmud” (2004) states in a section “the least you need to know” (p. 57): “Brachot (Blessings) is the longest tractate in words”.

As often happens with urban legends. once an assertion is accepted as “fact”, it is then claimed to have been verified. In the journal Ohr Torah (Sivan 5766 [465], p. 719) the claim is made that a computer check was performed and it was found that the largest masechet based on words is Berachot. But alas, it ain’t so and in the next issue of Ohr Hatorah (Tammuz 5766, p. 784) the error was pointed out.

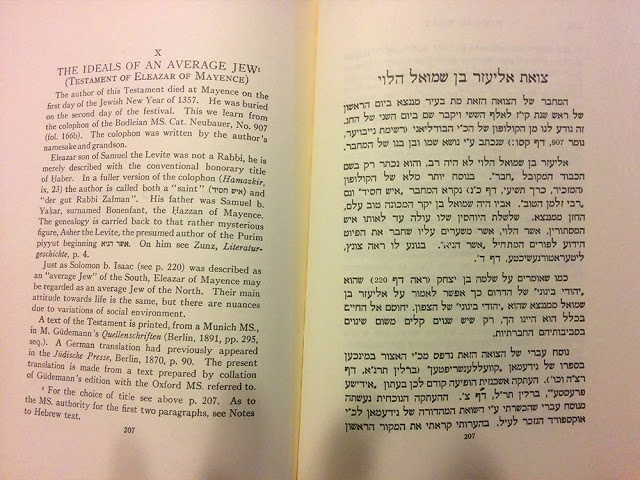

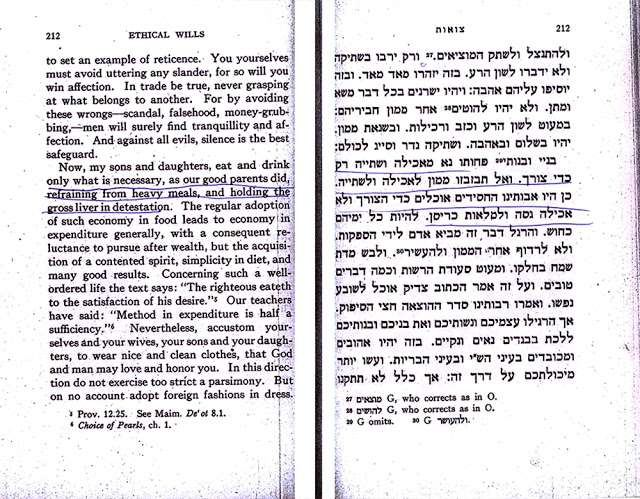

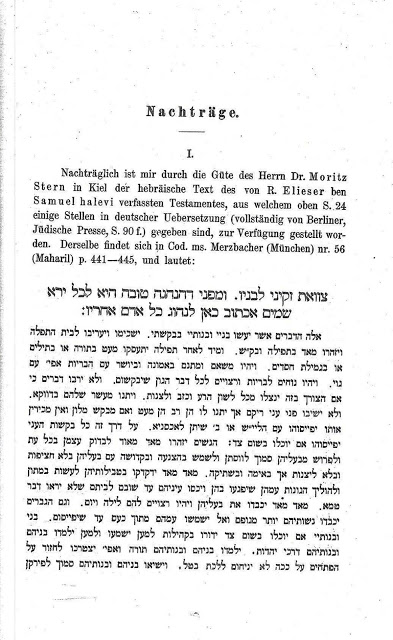

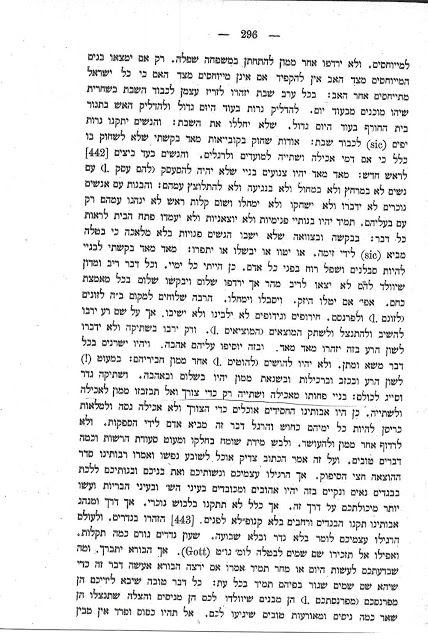

In actuality, and before presenting the results from a computer count, it is worth noting that ambiguity regarding sizes of masechtot only arose when commentaries began to be put on the same page as the text of the gemara. In other words, until the era of the printing press there was no ambiguity as to which masechta was the longest. Prof. Yaakov Shmuel Spiegel (Amudim B’toldot ha’Sefer ha’Ivri: Hagahot u’magihim [Chapters in the History of the Jewish Book: Scholars and Annotations], 2005, 105-106) credits Prof. Shlomo Zalman Havlin in his monumental “Talmud” entry in the Encyclopedia HaIvrit with the idea that the relative size of tractates can be determined based on the number of pages they occupy in the Munich manuscript. This unique manuscript, completed in 1342, was transcribed by one individual and had the entire Bavli in one 577 page volume. Simply comparing the number of pages of the various tractates provides the relative length in terms of characters/words. This ranking may be more accurate that a computer count of the words or letters as the single author may have been more consistent in terms of abbreviations and other factors that can influence the count.

Using the Munich ms, the rank ordering is similar, but not identical to that obtained from a computer count, although in all cases it is clear that Berachot is far from the largest. Using the Munich ms, the top five (with number of pages) are:

Shabbat (55.5)

Hullin (51)

Yevamot (47)

Sanhedrin (45.5)

Bava Kamma (45)

…..

Berachot (36) is number 11.

A similar system can be used to estimate the size of masechtot using the monumental one-volume shas edited by Zvi Preisler (Ketuvim Publishers, Jerusalem, 1998). It is straight text of Talmud with no commentaries of Rashi or Tosafot and is a uniform font. References to biblical verses are included and thus sections with more aggadatah might appear slightly longer. The text is arranged in three columns per page. Counting pages in this volume, the longest mesechtot (and number of pages) are:

Shabbat (77⅓)

Sanhedrin (66⅓)

Hullin (58⅙)

Bava Batra (56½)

Pesachim (55⅓)

Yevamot (55⅙)

…..

Berachot (47⅓ pages)

The simplest way to answer this question today is with a computer count of the number of words. Using the Bar Ilan Responsa project for this, the number of words in all of shas is about 1.865 million. And the 5 largest tractates are:

Shabbat (118k)

Sanhedrin (107k)

Hullin (90k)

Bava Batra (89k)

Bava Metzia (86.5k)

……

Berachot (73k) is in 11th place

The 5 smallest tractates are Chagigah (19k), Makot (18k), Horayoat (13k), Me’ilah 8k), and Tamid (5k). Other computerized calculations yield slightly different counts, but they do not significantly alter the rankings.

So why might one have been (mis)led to think that Berachot is the largest? It is easy to understand because Berachot does indeed win the prize in one category – words/daf. Berachot is king, with over 1115 words/daf. The next 5 are: Krisos (975), Horayot (972), Megilla (934), Sanhedrin (932 – the last perek probably plays a big role in raising this number!), Taanit (890). What might interest some daf yomi learners are the bottom 5, and those are (from bottom up): Nedarim (383), Meilah (384), Nazir (431), Baba Batra (509), Tamid (512).

The rumor is that the Gra stated that Berachot is the longest tractate, and it is hard to abandon such a tradition. A noble effort was recently made to vindicate that tradition. The book Mitzvah V’oseh (Shmuel David Hakohen Friedman, 2015, ch. 44, p. 564) quotes the famous statement that the Gra said Berachot is the longest in words, corrects this by pointing out that Shabbat is longer, and then gives a clever reinterpretation – the Gra was referring to Yerushalmi. And in the Yerushalmi, the author avers, Berachot is indeed the longest tractate by words. In a collection[1] of “trivia” that Rav Chaim Kanievsky was wont to discuss with his grandchildren, it is quoted that he said Berachot is the longest mesechta in Yerushalmi. That assertion is indeed much closer to being accurate but is still not correct.

In the Bar Ilan responsa project there are two versions of the Yerushalmi, the Vilna edition with almost 795k words and the Venice edition with almost 815k words, both considerably shorter than the Bavli.

In the Vilna edition of the Yerushalmi, the four largest tractates with their word count are:

Shabbat (47,685)

Yevamot (44,369)

Sanhedrin (40,008)

Berachot (39,478).

Using the Venice edition, the top four are:

Shabbat (49,161)

Yevamot (45,293)

Berachot (41,030)

Sanhedrin (41,004)

In the Yerushalmi too, one can use the monumental one-volume Yerushalmi edited by Zvi Preisler (Ketuvim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2006) to estimate the size of masechtot. Counting pages in this volume, the longest masechtot (and number of pages) are: Shabbat (37) and Yevamot (32 ⅔). This is followed by Brachot (30), Sanhedrin (29 7/9) and Pesachim (26 ⅔).

While these numbers are clearly influenced by many extrinsic factors such as which ms text used, abbreviations opened or closed, etc, they demonstrate that although Berachot is much closer to being the largest tractate in the Yerushalmi than it is in the Bavli, it is still behind the unquestioned largest in Bavli and Yerushalmi, Shabbat, and behind Yevamot.

Did the Gra actually make such a statement about what is the largest tractate in shas? There are no early records of it and I have not been able to find any mention of such a claim earlier than the late 20th century. Irrespective, the rumor that he stated that Berachot is the largest is fairly “common knowledge”. Yet it is clear using both counting ms pages and computer tabulated results, Berachot is far from being the largest in either the Bavli or Yerushalmi. Berachot does have one claim to fame in regard to size; it is by far the most words/pages.

[1] It is actually 175 pages; it goes up to page 176, but like all masechtot it starts on daf bet. But that would ruin the beautiful symmetry that the longest parsha in the Torah is naso with 176 pesukim and the longest chapter in Tanach is Tehillim chapter 119 with 176 verses.

[2] In Gedalia Honigsberg, “HaSeforim”, 5777, ch. 10 is “tests” Rav Kanievsky would give and pages 199-201 is trivia for the grandchildren. On p. 200 it states that the largest mesechta in Bavli is Bava Batra followed by Shabbat. It then quotes in the name of the Gra about Berachot being largest in terms of words but that it is unlikely he said that because in reality Shabbat is larger. It then says that in the Yerushalmi the largest mesechta is Berachot.