Mrs. Ethel Abrams – Ettel Ha’Ivriya of Clarksdale, Mississippi

By Rabbi Akiva Males

________________________

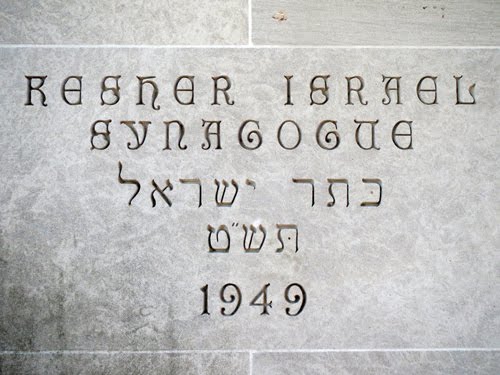

Introduction[1]

Stepping out of my car on Monday morning, July 3rd 2023, I received a warm welcome from the heat and humidity of Clarksdale, Mississippi. I opened the gate of the black iron fence surrounding the Beth Israel Cemetery and stepped inside. It didn’t take me long to survey the surprisingly well-maintained grounds where the members of that small Jewish community now rest in peace. Within a few minutes I found what I had come to see: the tombstone of Mrs. Ethel Abrams, of blessed memory.

Beth Israel Cemetery in Clarksdale, MS

Photo by Rabbi Akiva Males

The gravestone of Mrs. Ethel Abrams, a”h

Source: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86841744/ethel-b-abrams#view-photo=108781020

In the paragraphs that follow, I hope to answer the following questions:

-

Who was Mrs. Ethel Abrams?

-

Why did I drive nearly 75 miles from my home in Memphis, TN to visit her grave?

-

What is the history of the small Jewish community which once flourished in Clarksdale, MS?

Part I – The Story of Mrs. Abrams

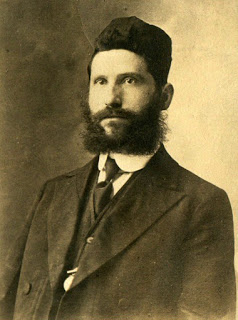

In January of 2017, I was researching the topic of using a flowing river as a Mikvah (see Rema to Shulchan Aruch YD 201:2, and Aruch Hashulchan YD 201:41-42). After Maariv one night, I approached Rav Nota Greenblatt, zt”l, while he was leaving Shul. I told him what I was looking into, some of the sources I had found, and inquired if anyone had ever asked him about this on a practical level. After all, the city of Memphis sits on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. I figured this question must have arisen over the nearly seven decades Rav Nota had been fielding – and resolving – all sorts of Halachic questions in Memphis (and far beyond).

Rav Nota stopped, looked me in the eyes, and with a grin on his lips he asked me if I was familiar with Clarksdale, MS. I shrugged, shook my head, and responded that I had never heard of the place. Rav Nota went on to tell me that a prosperous group of Jewish small business owners and their families had once thrived there. He explained that in his younger years, when he was an active Mohel, he had made the roundtrip from Memphis to Clarksdale on many occasions upon the birth of baby boys.

Rav Nota became serious as he continued his story:

“Sadly, other than a cemetery, there’s nothing left of Clarksdale’s Jewish community.” He explained that while economic forces were mostly responsible, other factors had also played a role. His eyes moistened as he described how religious observances – particularly those of Shabbos – became less and less prevalent among the immigrant Jews who had sought to earn their livelihoods in the Mississippi Delta.

In retrospect, the handwriting of religious decline was on the wall. Like so many other small communities across the US, Clarksdale had a very limited infrastructure to support traditional Jewish observance, a lack of readily available Kosher food, and no strong Jewish educational structure for their children. It was not long before the Orthodox practices with which most of that community’s Jews were once familiar were no longer part of their routines.

“However,” continued Rav Nota, “there was one woman in Clarksdale who wouldn’t let go. Her name was Mrs. Abrams, and she remained absolutely committed to Yiddishkeit. In fact, she tried her best to convince others around her to remain Shomer Torah U’Mitzvos.”

Rav Nota shared that there was one Mitzvah that Mrs. Abrams – whom he called as a Tzadeikes – succeeded in convincing others to observe. Mrs. Abrams was passionate about Taharas HaMishpacha and would speak to the young married women of Clarksdale about how important that Mitzvah was for their marriages, and their families’ futures. However, Clarksdale had no Mikvah. If women were not willing to travel nearly 75 miles to Memphis and back (before modern highways would make that journey more manageable) how could they possibly observe this Mitzvah? Amazingly, on many nights a month, Mrs. Abrams would accompany women from Clarksdale to the nearby Mississippi River where she would help them discreetly immerse in its murky moving waters!

Rav Nota became emotional as he shook his head and exclaimed, “Can you believe it? Mrs. Abrams would take women – just about all of whom were far from keeping Mitzvos – to be Tovel themselves in the Mississippi River! If I wouldn’t have known her, I never would have believed it. But I knew her well, and it’s true!”

I listened in astonishment as Rav Nota described how over the course of many years, Mrs. Abrams had personally reached out to the Jewish women of her community, and respectfully spoke to all who would listen. In an era when everyone around her was dropping Mitzvah observance, somehow, Mrs. Abrams succeeded in encouraging many women to keep Taharas HaMishpacha. She did not persuade those women to visit a pristine new Mikvah. On the contrary, on an untold number of nights, this heroine of the Delta accompanied numerous young marrying and married women to the nearby silt-filled Mississippi River. There, in a spot she had cordoned off along the muddy riverbank, Mrs. Abrams would serve as both a Mikvah lady and a lifeguard!

I was in awe as Rav Nota spoke about Mrs. Abrams. She wasn’t just some sort of a “last of the Mohicans” when it came to Halachic observance in Clarksdale. From the way Rav Nota described this incredible woman, she had been the catalyst for many Jewish women of her locale observing the Mitzvah which was most uniquely theirs. The fact that she succeeded to the degree which she did – and under the most challenging of circumstances – boggled my mind.

As I left Shul and walked Rav Nota to his car, he added another detail about Mrs. Abrams. In speaking with her on his numerous Bris Milah runs to Clarksdale, she had demonstrated extensive knowledge of the other small communities of Jewish merchants living in towns across Mississippi. As such, Rav Nota reached out to her on many occasions to verify the Jewish credentials of people originating from her environs when matters arose pertaining to marriages, Gittin, and funerals. He told me that he had trusted Mrs. Abrams absolutely, and that she had been a vital resource for him in a number of cases that had come his way over the years.

I remember making a mental note to find out more about Mrs. Abrams and Clarksdale, MS, but other pressing issues always seemed to demand my attention. I filed this conversation with Rav Nota in my notes, and I nearly forgot about Mrs. Abrams until the summer of 2023.

Part II – Clarksdale’s Jews in the News

On Monday afternoon, September 6, 1926 – almost 100 years before my visit to Clarksdale – two short items concerning that town’s Jewish community appeared on the local newspaper’s front page. The Clarksdale Daily Register’s two articles related to Rosh Hashanah – which would occur later that same week on Thursday, September 9th and Friday, September 10th.

The first piece was entitled “Jews Observe Holy Season”, and was subtitled “Services To Be Held For The New Year In Local Synagogue All Week”. The first and last paragraphs of that article read:

“Services commemorative of Rosh Hashanah or the Jewish New Year will be observed here at the Beth Israel Synagogue. Beginning Wednesday evening at 7:30 when the opening service will be held. Thursday morning services will begin at 8. Since the congregation is an Orthodox one, members will observe two days and services will also be held Thursday evening at 7:30 and Friday morning at 8 o’clock. Regular services for the Sabbath will be held Friday evening and Saturday morning …”

“ . . . The New Year’s day is one of solemn joy and greeting of the day “L’shanah tovah,” A Happy New Year, is heard on all sides in the homes and in the synagogue. The festival is observed two days, the 9th and 10th of September, by the orthodox Jew.”

Just two columns to the right, Clarksdale’s paper ran a second article pertaining to the local Jewish community’s observance of that year’s Rosh Hashanah. It was entitled: “Pupils Enroll For Semester”, and was subtitled: “Jewish Children May Enroll Saturday Since Thursday and Friday Are Religious Holidays”. The first paragraph of that article reads:

“Due to the fact that Thursday and Friday of this week are Jewish holidays, Supt. Heidelberg of the city schools announced this morning that all Jewish children would be expected to enroll at their respective schools Saturday morning at 8:30, and that it would not be necessary for them to be present on either of the holidays. However, it is very necessary that they be present Saturday morning, at which time they will be classified . . .”

.jpg)

From the front page of the Clarksdale Daily Register, Monday Afternoon, September 6, 1926

The sad irony of that second article was not lost on the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience.[2] Their newsletter of September 2022 opened with the following paragraphs:

“In 1926, the city of Clarksdale, Mississippi, unknowingly scheduled school registration for the two days of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. This didn’t sit well with the Jews of Clarksdale, so they asked for and got an accommodation: Jewish children could register for school on Saturday, instead of the Thursday and Friday of Rosh Hashanah.

This accommodation, in a way, encapsulates well the Southern Jewish experience: Clarksdale’s Jews stood up for their religious identity and the town acceded. But at the same time, there was an accommodation on the Jewish side, as well. Saturday is Shabbat, the Jewish sabbath. By the 1920s, most (but not all) of Clarksdale’s Jews were Reform, keeping their stores open on Saturdays, the busiest shopping day of the week. This was a necessity in a region where Sunday Closing Laws were the norm.

The Southern Jewish experience has always been about adapting, accommodating, and conforming to new surroundings, while at the same time embracing, sustaining, and celebrating our history, culture, and religious practices . . .”[3]

This commentary on the Clarksdale’s Jewish community’s 1926 Rosh Hashanah dilemma offers an eye-opening window into their struggles with religious observance. It also helps resolve the apparent contradiction between the two stories appearing on their newspaper’s front page. Although the first article twice stressed that the congregation was an Orthodox one, the second article described a synagogue whose membership overwhelmingly did not observe Shabbos in an Orthodox fashion. It seems that the condition of Clarksdale’s Beth Israel was much like that of many other early 20th century American synagogues. Though the congregation’s services may have been conducted in an Orthodox manner, by 1926, the lifestyles of many of that congregation’s families were not necessarily congruent with Halacha.

Discovering this eye-opening tidbit of Mississippi Jewish history made me curious to learn more about the Jewish community that once existed in Clarksdale.

Part III – Clarksdale: The Lifecycle of a Jewish Community in the Mississippi Delta

Thankfully, a good deal of research has already gone into the history of Clarksdale’s Jewish community. What follows are excerpts from two excellent articles published by The Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL)[4] and the Jewish Historical Society of Memphis and the Mid-South.[5] For the purpose of this article, I took the liberty of combining excerpts from both of those articles. I also rearranged the order in which some of those excerpts originally appeared.

“Clarksdale, Mississippi, sits on the Little Sunflower River a few miles east of the Mississippi River. The seat of Coahoma County, Clarksdale emerged as a trading hub in the late 19th century and has long served as an important cultural center for the Mississippi Delta region . . .

. . . The town’s population more than doubled during the 1890s, reaching 1,773 residents by 1900. Migrating African Americans—many of them formerly enslaved—contributed to this population increase, as they sought to make a living in the area’s booming cotton economy . . . .

. . . Prior to the depression of 1921, The Wall Street Journal reported Clarksdale as “the richest agricultural city of the United States in proportion to its population” . . .

. . . Jewish history in Clarksdale and surrounding towns dates to the arrival of German speaking Jews around 1870. Jewish organizational life began in the 1890s and continued to grow in the early 20th century. In the 1930s, the area’s Jewish population reached 400 individuals, and for a time Clarksdale boasted the largest Jewish community in the state. Although Jewish communal life remained vibrant into the 1970s, the Jewish population declined for the next few decades. In 2003 Clarksdale’s only Jewish congregation, Congregation Beth Israel, closed its synagogue . . .

. . . Jewish occupational patterns in Clarksdale mirrored trends not only in other developing towns in the Mississippi Delta but also in new sites of Jewish migration throughout the world. Jewish settlers often began as peddlers before founding dry goods or other retail stores, and they served customers from town as well as the surrounding countryside . . .

. . . By 1896, enough Jews lived in Clarksdale and the surrounding area to hold religious services. That year, five Clarksdale Jewish families founded a congregation known as Kehilath Jacob . . . Early worship services followed Orthodox practice . . .

. . . Kehilath Jacob continued to hold services in borrowed or rented spaces until 1910, when the congregation dedicated its first synagogue, a white stucco building at 69 Delta Avenue. With the erection of their first synagogue came a name change, and the congregation was known as Congregation Beth Israel from that point on . . .

Historic marker in front of Beth Israel Congregation’s first building in Clarksdale, MS

Photo by Rabbi Akiva Males

. . . As of 1920, the local community consisted of approximately 40 Jewish families in Clarksdale, with additional congregants in outlying areas . . . Temple Beth Israel accommodated a variety of Jewish observances during its early decades, but younger members began to push for Reform services with more English prayers. The rift between Orthodox and Reform congregants threatened to split the congregation during the 1920s, until the construction of a new synagogue in 1929 allowed Temple Beth Israel to hold two concurrent services on separate floors . . .

. . . The Orthodox members used the lower auditorium and the Conservative and Reform used the upper floor. It was the only synagogue in Mississippi that provided for Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform worship in the same sanctuary . . .

. . . As the 20th century progressed, Jewish shops remained a visible presence in downtown Clarksdale. Of fifteen dry goods stores listed in Clarksdale’s 1916 city directory, at least two-thirds belonged to Jewish merchants. Other Jewish retail businesses included “general goods” and grocery stores, as well as later department stores . . .

. . . The arrival of Rabbi Jerome Gerson Tolochko in 1932 marked a turning point for Beth Israel. Not only was Rabbi Tolochko the congregation’s first formally ordained resident rabbi, but his training at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati reflected the Jewish community’s movement toward Reform Judaism . . .

. . . Clarksdale was home to nearly 300 Jewish residents at the end of World War II . . . In 1970 Congregation Beth Israel still claimed 100 families, but a series of economic changes had begun to have a visible effect on the Jewish community. The agricultural labor force in the Mississippi Delta had declined in preceding decades, as a consequence of New Deal programs that paid landowners to reduce crop production and the introduction of mechanical cotton pickers in 1947. As the number of sharecroppers and other agricultural workers decreased, so too did the customer base for many Jewish retail stores . . .

. . . During the late 20th century, the rise of chain discount stores accelerated the decline of Jewish retail businesses, and Clarksdale’s Jewish population continued to shrink . . . Many members relocated to Memphis but continued to support the Clarksdale congregation and maintained ties to the Clarksdale community.

In the early 21st century, Beth Israel’s remaining 20 members decided they could no longer sustain a congregation. They made plans to close the synagogue and organized a deconsecration service on May 3, 2003 . . . The building was ultimately sold, leaving the Jewish cemetery as the landmark that most explicitly testifies to the existence of a once vibrant Jewish community . . .”

Elsewhere,[6] I learned that Beth Israel’s cemetery was established in 1919. In recent decades, a fund was established to ensure the perpetual care of the final resting place of Clarksdale’s Jewish community. Indeed, I can attest to that cemetery’s dignified upkeep.

Part IV – Finding Mrs. Abrams

Rav Nota Greenblatt’s amazing story about Mrs. Abrams had piqued my curiosity about Clarksdale’s Jewish history. The articles I discovered helped me better understand that community’s rise and decline. However, as I reflected on Mrs. Abrams’ excursions to the Mississippi River with the Jewish women of her locale, there were more details I wanted to learn about that incredible woman:

-

What was her first name?

-

What was her background?

-

How did she remain so committed to Torah and Mitzvos in a place without a supportive populace or infrastructure?

-

What compelled her to remain in Clarksdale when she obviously desired to live a fully observant Jewish life?

-

How did she deal with Clarksdale’s 1926 Rosh Hashanah / Shabbos dilemma?

-

How did she successfully convince numerous women who were not seriously committed to Jewish observance to use the Mississippi River as a Mikvah?

-

How did she ensure the safety of the women she led into that mighty river?

Unfortunately, on Friday, April 29, 2022 (28 Nissan 5782) Rav Nota Greenblatt, zt”l, passed away. Although I asked some of Rav Nota’s children and Talmidim if they had more information on Mrs. Abrams, no one seemed to know more about her than what he had shared with me.

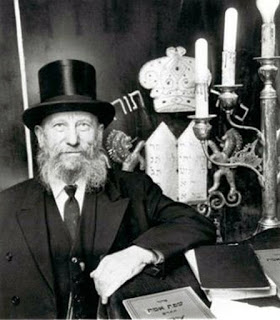

Rav Nota Greenblatt, zt”l, in his home study on Erev Pesach 2017

Photo by Rabbi Akiva Males

Through some internet sleuthing, I discovered a grandson of Mrs. Abrams, and he was excited about my interest in his grandmother.

When we spoke, I learned that her first name was Ethel, she was born on December 10, 1876, and that she hailed from a renowned Rabbinic family named Bronitsky from the vicinity of Minsk and Pinsk in Russia (modern-day Belarus). Ethel married her husband David (1877 – 1947) back in the Old Country, and that’s where their daughter and son were born. In search of a livelihood, David Abrams came to America in either 1904 or 1905, and a job opportunity brought him to Clarksdale, MS. The family was reunited in 1908 when Ethel and her two children were able to join David in Clarksdale.

According to family tradition, Mrs. Abrams was deeply unhappy about the decreasing levels of Jewish religious observance she witnessed all around her. Her determination to adhere to the Torah and Mitzvos must have caused her to feel quite isolated – yet she held firm. I learned that Mrs. Abrams raised chickens in her backyard, and that her husband would travel to Memphis by train with some of them on Friday mornings. Once there, they would be properly slaughtered, and he would take the train back to Clarksdale so those chickens could be prepared for Shabbos. Memphis was also where the Abrams family procured the Matzah and other staples they required for Pesach. On December 8, 1968 Mrs. Ethel Abrams passed away – just two days shy of her 92nd birthday.

I told Mrs. Abram’s grandson the beautiful story Rav Nota had told me about her, the Mississippi River, and the numerous Jewish women of Clarksdale who observed Taharas HaMishpacha because of her. He was not aware of these details about his grandmother, and he greatly appreciated my sharing those gems with him.[7]

As our friendly conversation drew to a close, I felt glad to have gained many biographical details of Mrs. Abrams’ life. Unfortunately, I also realized that I would never learn all that I wanted to understand about her. After all, no one could truly answer my questions about her thoughts and experiences other than Mrs. Abrams herself – and she did not seem to have left a written record before passing away in 1968. I thanked Mrs. Abrams’ grandson, and told him that I looked forward to visiting Clarksdale in the coming weeks.

Part V – Visiting Mrs. Abrams

As I stood before Mrs. Abrams’ tombstone on that July morning, I thought about her iron-clad resolve to remain true to Torah and Mitzvos in the midst of the most trying times and circumstances. I glanced at the many graves to her right and left and wondered how many of those neighbors had immersed themselves in the Mississippi River because of her. I recited a Perek of Tehillim followed by a Kel Maleh, and I pledged to give some Tzedakah in memory of that Tzadeikes upon returning to Memphis. As I exited Beth Israel’s cemetery, I looked back, and mentally bid farewell to Clarksdale’s Jewish community. After shutting the gate behind me, I returned to my car.

While driving back to Memphis, I thought of the famous Midrash[8] about why the Torah refers to Avraham Avinu as Avraham Ha’Ivri.[9] According to Chazal, Avraham did not simply come to Canaan from the other side of the river (which the word Ha’Ivri connotes in its plain meaning). Rather, Avraham Avinu earned the honorific title of Ha’Ivri because he found the strength to swim against the tide – living a life that was distinct from all who surrounded him. Even when the rest of the world metaphorically positioned themselves on one side of a river, Avraham was at peace remaining in solitude on the other side. Furthermore, not content in just behaving differently than his neighbors, Avraham Avinu also tried his best to persuade a great number of them to join him in his worldview and way of life – on his side of the river.

Like her forefather Avraham Ha’Ivri, Mrs. Ethel Abrams found the strength to go her own way, and not live her life by following the crowd. Regardless of her surroundings, Mrs. Abrams followed her own convictions, and also did her best to persuade others to observe Mitzvos – especially Taharas HaMishpacha. The river associated with Avraham Ha’Ivri was the Euphrates. In Mrs. Abrams’ case it was the Mississippi. After visiting her grave, I will always associate this Midrash with her. As far as I’m concerned, Mrs. Ethel Abrams was Ettel Ha’Ivriya of Clarksdale, MS.

Yehi Zichrah Baruch.

_____________________

Rabbi Akiva Males serves as the Rabbi of Young Israel of Memphis. He also teaches at the Margolin Hebrew Academy-Feinstone Yeshiva of the South. He can be reached at rabbi@yiom.org

.jpg)